Background to lean thinking transformation in healthcare

In the future, NHS and foundation hospital trusts will be expected to address the twin challenges of improving quality of care and reducing expenditure.1,2 They will need to adhere to outcome and performance measures, increase efficiency and improve patient satisfaction using more individualised healthcare processes.3 They risk the decommissioning of services considered to be poor value for money or poorly responsive to patients and their transfer to independent sector and primary care organisations. Facing such demands, hospital consultants and their managers may be uncertain how to develop or even maintain their specialties within secondary care, or how to adopt new methods of operating, redefine staff roles, and refocus on the customer base (the patients).

An established system of process redesign, lean thinking transformation has demonstrated both success and sustainability in improving performance and quality in manufacturing industries, that are commonly subject to competitive markets with a plurality of providers (as now occurs within healthcare). It is a system that has been proposed as transferrable to hospital-based specialist care to improve efficiency and quality in patient management.4

On this basis, lean thinking transformation has been trialled by many trusts in the UK supported by consultancies such as the Lean Enterprise Academy and the Manufacturing Institute. However, its effectiveness in changing healthcare practice remains questionable with few reports in the published literature of sustained service transformation. Furthermore, the evidence that it has been adopted by the medical profession as a basis for service redesign is limited. Uncertainty, therefore, remains as to how this apparently effective technique can assist hospital consultants and their managers in developing services.

The role of lean thinking transformation in healthcare

Originating in post-war Japan where it contributed to the revival of a shattered motor manufacturing industry,5 lean thinking transformation redesigns processes around customers and staff, identifying and removing unnecessary obstacles to efficient practice. It entered US healthcare organisations such as the Virginia Mason Center in Seattle a decade ago, with the aim of providing a patient-centred approach to medical management, and was credited with improving both clinical outcomes and activity.6,7

In order to understand lean thinking transformation in healthcare, the patient pathway must be seen as a process consisting of identifiable steps between two defined points (eg admission to an accident and emergency department to discharge from the ward).8 In common with industrial processes, patient pathways are subject to process failures including bottlenecks, periods of inactivity (waiting times for staff and patients) and waste (activities that do not add value to the patient journey). Lean thinking transformation provides a framework for removing these process failures and restricting the constituent steps to interventions that contribute to the proposed outcomes, thus increasing efficiency, improving the patient experience and reducing demands on staff time.9

How to make lean thinking transformation work in healthcare

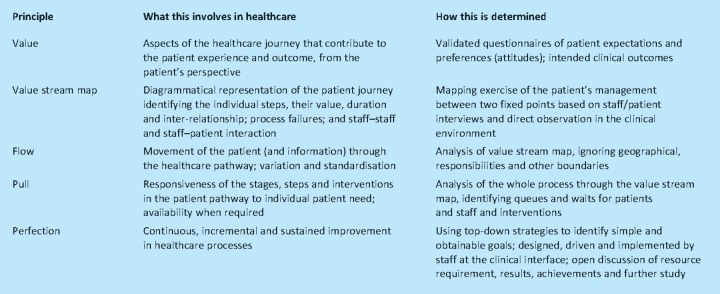

In the classic text by Womack and Jones, five core components to lean thinking transformation are described (Table 1).10 These are as relevant to process redesign in healthcare as in the manufacturing industries.11 In addition, the methodology used to obtain and interpret data may influence the nature and validity of the results, and objectives of subsequent service development.

Table 1.

At the heart of lean thinking transformation, is the identification of value-adding steps that contribute to the proposed outcome, and that are determined from a customer (patient) perspective. The NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement advocates that mapping a process effectively is dependent on investing time and resources into determining exactly what aspects of their care patients consider most important.11 This may require a local patient survey or literature review of published patient attitude studies. By comparison, staff opinion and discussion alone are unlikely to provide accurate and valid understanding of patient priorities.

Secondly, obtaining accurate data is essential to the quality of the results of any study. Undertaking interviews within the clinical environment allows the engagement of those staff exposed to admission, equipment preparation, patient transportation and other routine processes that account for the majority of the patient journey and most of the process failures. Interviewees should feel comfortable in providing honest opinions; this is dependent on gaining trust and familiarity with all relevant staff with the added advantage of increasing staff interest in such exercises and enabling implementation. Thirdly, scientific analysis of mapping data is required, looking for unnecessary variation in duration of activities and the interdependence of steps. Meaningful interpretation of the results may require inclusion of both the consultants and junior doctors routinely involved in the service and managers with experience and expertise in lean thinking. Finally, robust methods of determining the response to service redesign and the need for further improvement are essential to demonstrating the benefits of the exercise but require longer-term study, including repeated mapping or audit.

Focusing lean thinking exercises on patient-determined priorities, using a more scientific approach to obtaining data and its interpretation, and engaging with clinical staff, is essential for persuading consultants that the time invested in such exercises is worthwhile and relevant to their practice. By comparison, undertaking selective, albeit less demanding, process mapping exercises run by a small, select, senior group, in a non-clinical environment, risks limiting results to a simple description of the events in a pathway without relevance to patients, staff or their priorities. This provides neither the opinions relevant to the problems in the service nor the opportunity to obtain them.

Using lean thinking transformation to change hospital culture

Studies of lean thinking transformation in manufacturing industries emphasise its role in changing organisational culture beyond individual processes.5,10 This too is relevant to managing services in healthcare. Lean thinking would argue that the introduction of all new policies or initiatives from organisational to departmental level should be reviewed with respect to their effect on patients' priorities, staff time and the flow of healthcare pathways. This may extend from the introduction of new procedure request forms, to committees for the agreement of new drugs or technologies, or the redeployment of staff or their roles.

A culture of lean thinking allows us to ask much broader questions about hospital organisation, such as the contribution of large medical admissions wards (that may be considered as inventory stores) or new IT systems (introducing complexity to a process without adding value). Often it directs us to simple and inexpensive methods of improving our service such as the use of adequate labelling on shelves (visible signals) or ensuring that junior doctors don't leave the ward to drop off blood tests bottles or request forms (cellular model of workplace design). In such circumstances lean thinking principles could be a core component of strategic planning from executive to departmental level.

Moving forward with lean thinking transformation

If undertaken successfully, lean thinking transformation can be an effective method of redesigning hospital processes.4 It offers a framework for addressing many of the challenges that NHS and foundation trust specialist services face. Undertaking such exercises requires considerable investment of time and effort, the engagement of busy staff at all levels, including junior and consultant medical staff, and determination of patient priorities in their care. The use of clear objectives in a well-planned exercise with appropriate interpretation of results can form the basis of service redesign that is both sustained and relevant to doctors and their patients.

References

- 1.Nicholson D. Update; Department of Health. This month 2011 January 31:1–2. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Bulletins/themonth/index.htm.

- 2.Dixon J. Improving efficiency in the NHS in England: options for system reform. Clin Med. 2010;10:445–9. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.10-5-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coulter A, Fitzpatrick R, Cornwell J. The point of care, measures of patients' experience in hospital: purpose, methods and uses. London: The Kings Fund; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graban M. The case for lean hospitals. Lean Hospitals. 2009:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liker JK. The Toyota way. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim CS, Spahlinger DA, Kin JM, Billi JE. Lean health care: what can hospitals learn from a world-class automaker? J Hosp Med. 2006;1:191–9. doi: 10.1002/jhm.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albright B. Lean and mean. Health Informatics. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trebble TM, Hansi N, Hydes T, Smith MA, Baker M. Process mapping the patient journey: an introduction. BMJ. 2010;341:c4078. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mould G, Bowers J, Ghattas M. The evolution of the pathway and its role in improving patient care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:e14. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.032961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Womack JP, Jones DT. Lean thinking. 2nd edn. London: Simon & Schuster UK Ltd; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westwood N, James-Moore M, Cooke M. Going lean in the NHS. London: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement; 2007. [Google Scholar]