Abstract

Diagnostic error underlies about 10% of adverse events occurring in hospital practice. However, there have been very few studies considering means of improving the mechanisms of diagnosis. As a result, misdiagnosis has been described as ‘the next frontier for patient safety’.1 In this study of case records of patients admitted to hospital as emergencies, some key factors that may underlie diagnostic errors were assessed. From these observations, possibilities for improving the quality of diagnosis and the planning of subsequent care are explored. This paper shows that cognitive biases, believed to distort diagnostic conclusions, can be applied quite specifically to stages in clinical care. These observations led to the proposal of a clinical assessment with a method designed to encourage analytical reasoning. In addition, minor defects in standard practice are shown to adversely influence diagnosis. The findings of this study offer possible means of improving the quality of diagnosis and subsequent patient care, and perhaps pave the way for prospective studies.

Key Words: analytical reasoning, case record review, cognitive bias, diagnostic error, tabulated clinical summary

Introduction

Diagnostic errors underlie a significant proportion of adverse events in hospital practice. In the early Harvard study2 the incidence of diagnostic error (14% of total errors) exceeded that of medication error (9%) and carried a significantly worse prognosis, yet published studies of medication error far exceed those of diagnostic error. In the USA, misdiagnosis (26%) now rivals surgical accidents (25%) as the leading cause of medicolegal claims.3 Regrettably, such data are not readily available elsewhere. In England and Wales, the NHS Litigation Authority is responsible for all medicolegal claims in the public sector and does not allow access to the data for research. With misdiagnosis, often days pass between the first opportunity to make the correct diagnosis and the realisation that an error has occurred, and usually there is no opportunity to discuss the issues with the clinicians involved. In the USA, there has been one large study of misdiagnosis based on aggregates of confidential reports made by physicians from 22 healthcare settings.4 This showed that diagnostic errors were spread over a wide spectrum of disease (with pulmonary embolism and drug reactions the most common - although each provided only 4.5% missed diagnoses). The authors concluded that analyses of such errors could indicate potential preventive strategies.

In a comprehensive review of previous studies of misdiagnosis, diagnostic errors were assigned to one of three categories: no fault, system-based and human-cognitive.5 ‘No fault’ included unusual or silent presentation of disease and cases in which patients provided confusing descriptions of symptoms; ‘system errors’ included technical and organisational malfunctioning; and human-cognitive failures included the faulty gathering of data, inadequate reasoning and faulty verification. Allocation of errors to such broad categories varies because systems are rarely clearly defined and clinical considerations are difficult to assess. The authors of a comprehensive Dutch study concluded that, for diagnostic adverse events, human cognitive factors played a significant part in 96% and system failures in only 25%.6 In contrast, an American study found cognitive errors important in 74% and systems-based failures in 65%.7

Minimising cognitive errors that enhance the incidence of misdiagnoses requires thought and understanding. In emergency departments, in family doctor clinics and in hospital wards for the acutely ill, resources are usually stretched and time is limited. In such environments, diagnosis often depends on perception and intuition rather than analytical thought, even when there is considerable uncertainty. Such processes are susceptible to the types of error that Croskerry calls ‘cognitive dispositions to respond’.8 To limit such biases in decision-making, clinicians need enough time to consider alternative possibilities and to analyse the evidence (even, perhaps, unconsciously applying Bayesian concepts of probability).

Aims of the study

The clinical diagnoses of patients admitted to hospital as medical emergencies often evolve as illnesses progress. The cognitive biases that may affect diagnostic thinking have been explored in depth although not chronologically.8,9 This study aimed to firstly define likely biases in reasoning in relation to the progress of the diagnostic process, and secondly to encourage behaviour designed to improve diagnostic analyses.

Over the past decade, members of our unit have undertaken several studies of adverse events based on case record review.10–13 This method has been shown to be particularly useful if it is undertaken with the involvement of providers of care - doctor trainees, senior ward nurses and ward pharmacists.13 From these studies of more than 2,500 case records of emergency admissions, examined over several years, the likely biases in cognitive reasoning in 21 cases of misdiagnosis have been assessed.

Methods

In the first stage of the study, the senior clinical reviewer (GN) aimed to identify potential faults in reasoning during the progress of patients' illnesses, by referring to previously well-characterised cognitive biases.8 Subsequent discussions with trainee doctors, the fellow case record reviewer (HH) and finally with an expert in decision making (NS), who was blinded as to the original case material, led to the definition of stages at which particular cognitive biases were most likely to occur. Differences in opinion were resolved by discussion.

In the second phase of the study, one case was considered in depth to determine the presence and impact of biases in diagnostic reasoning and the adverse effects of apparently minor defects in standard practice. The extensive psychological literature on cognitive processes was then drawn upon to produce a method designed to encourage analytical reasoning.14

Findings

Classification and application of cognitive dispositions to respond

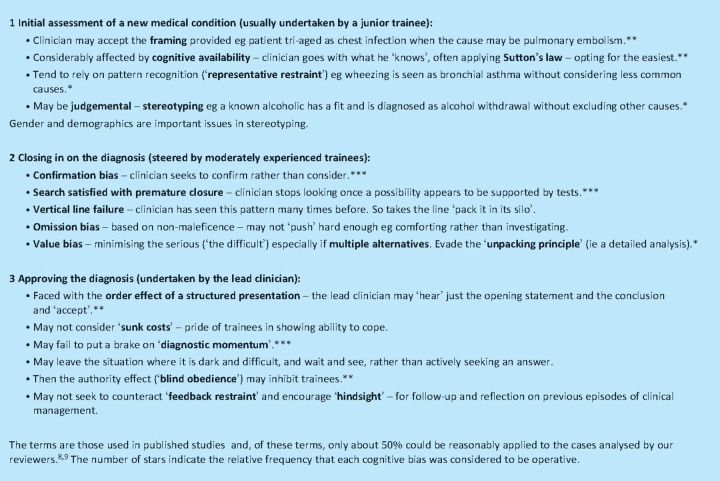

Detailed analyses of the 21 cases revealed the potential presence of cognitive biases that alter in pattern as patients pass under the ladder of supervisory care (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cognitive biases at key stages of patient management.

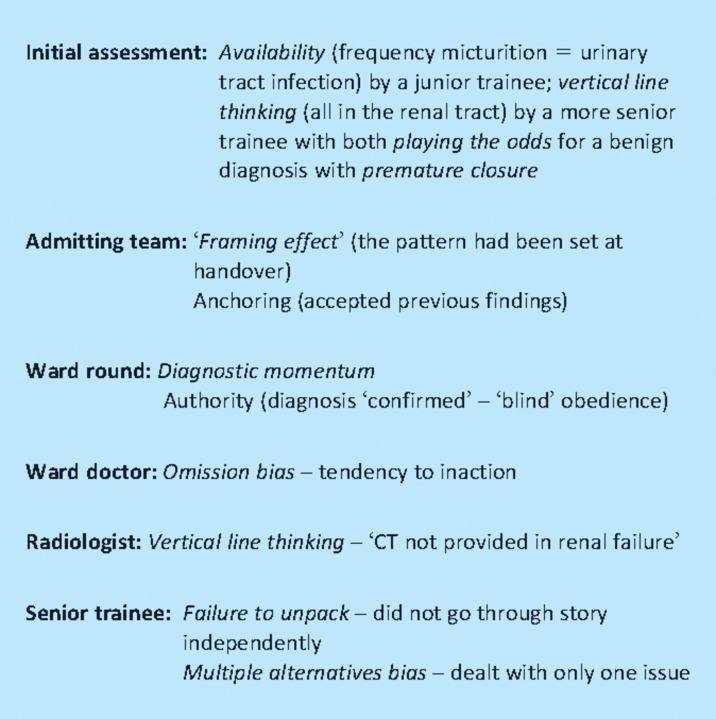

Case study (with cognitive biases that may have affected the diagnostic process - Table 2)

Table 2.

Cognitive biases identified in case study.

A 78-year-old woman presented to her GP with frequency of micturition and constipation. A mid-stream specimen of urine (MSU) was taken and she was prescribed co-trimoxazole. Four days later, when she had developed lower abdominal pain, she was referred to hospital for a surgical opinion. She had several co-morbidities including diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart disease with atrial fibrillation, thyroid insufficiency and previous surgery for nephrolithiasis. Junior members of the surgical team found a soft abdomen with some suprapubic abdominal tenderness in a patient who had passed flatus recently and in whom rectal examination was recorded as normal. An abdominal radiograph was also recorded by the clinician as normal although, in retrospect, there were subtle abnormalities. The patient was apyrexial. Standard blood tests showed haemoglobin 11.8g/100 ml, white cell count 20.3 (neutrophils 18.1) ×109/l, urea 14.1 μmol/l, creatinine 224 μmol/l, C-reactive protein 253 μmol/l. Urine examination showed ‘Blood trace, Protein +, Leukocytes 0, Nitrites -ve’. The initial diagnosis was stated under the heading ‘‘Imp’ - urinary tract infection; acute renal failure; sepsis ?urinary in origin.’ The doctors concluded that the problem was ‘non-surgical’ and transferred the care of the patient to a medical team.

The admitting doctor on the medical ward undertook a more comprehensive general examination but accepted the original diagnosis. The patient was prescribed co-amoxyclav and intravenous (iv) fluids together with her 12 usual medications including digoxin. The following morning, at the on-take ward round, the diagnoses were accepted and a note made indicating standard follow-up for a urinary tract infection. At the end of day two, the ward doctor on duty noted that the MSU sent by the GP the previous week showed 100 leucocytes per high power field but yielded no bacterial growth. This key information did not influence the management of the patient. On day three the abdomen appeared slightly distended. Computed tomography scanning was ordered but refused on the grounds that the patient had renal insufficiency (even though the levels of urea and creatinine were improving after iv infusion of fluid and electrolytes). An ultrasound examination was arranged for the following day.

On the morning of day four a nurse recorded the patient's blood pressure as 105/80 (previous reading 155/100) but took no action as this did not trigger the ‘early warning signal’ of ‘systolic less than 100’. The patient was seen by a senior trainee who listed the problems recorded on admission and showed concern that treatment with digoxin had been continued. In the mid-afternoon the patient collapsed. A straight radiograph of the abdomen revealed free gas. A surgical opinion was sought but the patient was regarded as too ill for laparotomy. She died that evening. Examination, post-mortem, revealed a perforated colonic diverticulum in the pelvis.

Considerations from these studies

Firstly, clinical examination remains a vital part of good clinical practice despite the large increase in available investigative procedures. Terminology may influence behaviour. It is standard practice to use the term PR (per rectum) that may lead a clinician to consider just the rectum and not the pelvis. In the case described, the GP referral letter (which was either not read or the contents ignored) indicated a ‘tender’ pelvis. Trainees do not get sufficient training in pelvic examination.15 To remind clinicians not to ignore the pelvis perhaps the term ‘PR (per rectum)’ might be replaced by ‘RPE’ (rectal and pelvic examination).

Secondly, it is standard practice to fill in a request form for a specific test rather than asking a colleague in the department of investigation to help solve the problem. In this case, discussion with a radiologist should have led to an appropriate scan of the pelvis and the diagnosis. Thirdly ‘system fixes’ carry risks. They may create new problems. The early warning system on the patient's observation

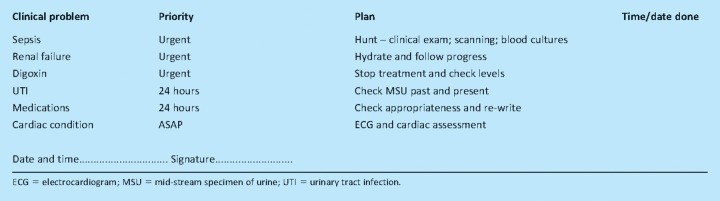

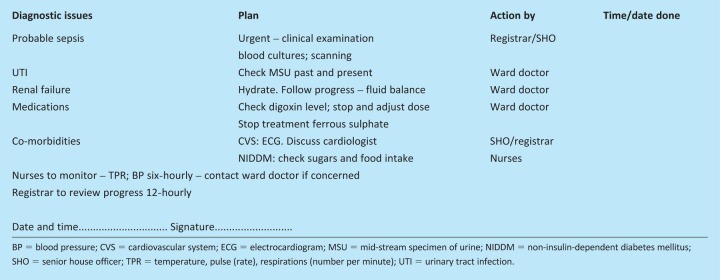

chart left the nurse with a false sense of security. Or maybe the system had ‘de-skilled’ her. Before the use of early warning systems, a competent nurse would have called attention to a sudden large drop in systolic blood pressure. Finally, over-reliance on a simple perceptive approach to diagnosis may forestall analysis. For the past several years, in the UK, this behaviour has been re-enforced by doctors completing their written assessment in case records with the term ‘imp’ (impression) rather than the previously more thoughtful ‘differential diagnosis.’ It is suggested that the situation might be improved by doctors being encouraged to change from intuitive to analytical thinking by tabulating clinical problems, in order of perceived importance, together with actions to be taken. Two possible formulations of analysis and action plans are presented in Tableas 3a and 3b. They include check boxes that may help ward doctors to remain focused on the problem as shown to be of value in a recent study from the Netherlands.16

Table 3a.

Suggested analytical process to be applied at end of a clinical assessment.

Table 3b.

Alternative analytical process at the end of a clinical assessment. clinical assessment.

Discussion

As Reason has stated ‘Our propensity for certain types of error is the price we pay for the brain's remarkable capacity to think and act intuitively’.17 Only recently has there has been a call to start devising and publishing means of minimising such errors. Observers of US healthcare believe that their system tolerates a background rate of diagnostic errors, providing that practitioners or hospitals are not wild outliers. They show that the costs of the ensuing events are rarely, if ever, uncovered, just quietly absorbed.18 It is suspected that this is a near-universal situation. In the UK, the national focus has been on incident reporting through the National Reporting and Learning System of the National Patient Safety Agency. This has facilitated the reporting of clearly defined incidents but not of diagnostic ‘errors’ which make up only 0.5% of reports. Understandably, clinicians are reluctant to discuss their errors.

Between 2002 and 2006, in an attempt to reveal the nature of problems in diagnosis, the American College of Physicians published a series of articles providing details of conferences, based on case reports drawn from institutions from around the USA.19 In one report from this series the author and discussants attempt to define corrective strategies to counteract cognitive processes that lead to misdiagnoses. These included the application of Bayesian reasoning, reconsidering diagnoses in the light of new data and examining problems anew. The authors suggested that trainees should be encouraged to return to the bedside if they remained less than fully convinced about a diagnosis approved by a more senior member of staff.9 Such behaviour patterns are difficult to inculcate in trainees and justify regular open discussion of cases in which management has been unsatisfactory. With the increasing complexity of hospital practice, input from more than one specialist is frequently required and, all too often, no one doctor takes responsibility for the overall situation. The problem is compounded by the need to restrict the working hours of the trainees. In the case record of the patient described in this communication, six trainees were involved - so within the four days there were multiple handovers with no one doctor having a sense of ownership. Follow-up and reflection are essential for improving diagnostic skills. The value of weaving this approach into the teaching process of trainees has been recently explored in the Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, USA.20

Accurate diagnosis requires integrating correct clinical findings with appropriate investigations and framing conclusions accurately. Intuitive thought and action play an important role in this endeavour and will continue to do so. Trainees, however, have to learn to remain open-minded in order to counteract natural biases in human thought processes. It seems reasonable to suggest that they should be taught to be aware of such biases and so take steps to counteract. This requires reflection, discussion and reconsideration. If still in doubt there will be a need for a second opinion. Ideally that second opinion should come from a more experienced clinician who must be prepared to analyse the problem without being biased by previous assessments. Systems designed in trusts to streamline the management of patients tend to evolve into mechanisms for efficiency (as with the failure of the clinicians to speak with a radiologist and the use of early warning systems described in the case study) rather than helping foster the creativity needed for elucidating the less obvious diagnoses. From the case study described, it is suggested that it may be valuable to structure the conclusion of a clinical assessment in a tabulated form that pushes the clinician to move from intuitive to analytical thought processes and to adopt a more comprehensive approach to the patient's problems by providing directions for further action.

The principal aim of this communication is to help clinicians to recognise pitfalls in making a diagnosis, especially when they rely heavily on intuitive thought processes. The importance of the recording process is obvious and a strategy that may encourage the improved analysis and management of clinical problems is suggested.

Acknowledgements

GN is grateful for the support of Lord Ara Darzi, head of the Academic Department of Surgery, Imperial College, St Mary's Hospital and of Professor Charles Vincent, head of the Imperial Centre for Patients Safety and Quality (PSSQ).

Funding

GN and NS are affiliated to the Imperial Centre for PSSQ which is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The preventable incidents, survival and mortality study (PRISM) is also funded by the NIHR.

Ethics approval

Material for this paper was drawn from previous studies of case records all of which had been approved as described in subsequent publications.11–13 The authors sought advice from the Centre of Research Ethical Campaign (COREC) regarding ethical approval and were informed that official approval was not needed as the primary aim of this study was for service improvement. Ethical approval for the PRISM study was obtained from the research ethics committees of the Institute of Neurology and the National Hospital for Neurological Diseases. The case study discussed in this paper has been considerably modified in order to achieve anonymity.

Authors' contributions

GN developed the ideas underlying this study following discussions on decision making with NS. The case described was obtained in the course of a pilot study for the PRISM investigation in which HH is the principal investigator.13 GN and HH ascribed cognitive biases after discussion with NS and trainee hospital doctors.

References

- 1.Newman-Toker DE, Pronovost PJ. Diagnostic errors–the next frontier for patient safety. JAMA. 2009;301:1060–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leape L, Brennan TA, Laird N, et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:377–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102073240605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CRICO/RMF. 2010. Protecting providers. Promoting safety. www.rmf.harvard.edu/high-risk-areas/diagnosis/index.aspx.

- 4.Schiff GDF, Hasan O, Kim S, et al. Diagnostic error in medicine: analysis of 583 physician-reported errors. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1881–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graber M, Gordon R, Franklin N. Reducing diagnostic errors in medicine: what's the goal? Acad Med. 2002;77:981–92. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zwaan L, de Bruijne M, Wagner C, et al. Patient record review of the incidence, consequences and causes of diagnostic adverse events. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1015–21. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1493–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.13.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003;78:775–80. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redelmeier DA. The cognitive psychology of missed diagnoses. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:115–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-2-200501180-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neale G, Woloshynowych M, Vincent CA. Exploring the causes of adverse events in NHS hospital practice. J R Soc Med. 2001;94:322–30. doi: 10.1177/014107680109400702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen S, Neale G, Schwab K, et al. Hospital staff should use more than one method to detect adverse events and potential adverse events: incident reporting, pharmacist surveillance and local real time record review may all have a place. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:40–4. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neale G, Chapman EJ, Hoare J, Olsen S. Recognising adverse events and critical incidents in medical practice in a district general hospital. Clin Med. 2006;6:157–62. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.6-2-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hogan H. Preventable incidents, survival and mortality study (PRISM) Ongoing study funded by the National Institute for Health Research.

- 14.Larrick LP. In: Blackwell handbook of judgment and decision making. Koehler D, Harvey N, editors. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. Debiasing. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfberg AJ. The patient as ally–learning the pelvic examination. New Engl J Med. 2007;353:889–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Vries EN, Prins HA, Crolla RM, et al. Effect of a comprehensive surgical safety system on patient outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1928–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0911535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reason J. Human error. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas EJ, Brennan T. Diagnostic adverse events: on to chapter 2. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1021–2. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wachter RM, Shojania KG, Markowitz AJ, Smith M, Sanjay S. Quality grand rounds: the case for patient safety. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:829–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-8-200610170-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMahon GT, Katz JT, Thorndike ME, Levy BD, Loscalzo J. Evaluation of a re-design initiative in an internal-medicine residency. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1304–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0908136. (with commentary N Engl J Med 2010;362:1593–5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]