Abstract

An electronic survey was used to assess perceptions of the disruption caused by the August transition and explore support for possible solutions. In total, 763 responses from members and fellows of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and the Society of Acute Medicine were received. The majority perceived the August transition to have a negative impact on patient care (93.1%), patient safety (90.4%) and training (57.8%) for a period of up to one month. In total 680/737 respondents wished to shift away from a single changeover day, with strong support for a staggered changeover by grade. Changes to consultant working practices were felt to be beneficial, especially the cancellation of outpatient clinics (75%) and the restriction of leave (69.9%). Further use of shadowing (74.1%) and online induction (37%) was supported. This paper concludes that there is a high degree of support for structured change to the current provisions for junior doctor changeover.

Key Words: August transition, medical education, pre- registration house officer

Introduction

August has historically been the start date for pre-registration medical trainees in the UK. The resulting changeover of an estimated 50,000 doctors on the first Wednesday in August has long led to concerns about patient safety, as well as the effective functioning of hospitals as a whole. The concern that junior doctor changeover represents a period of instability and poor safety is not confined to the UK, with the ‘July phenomenon’,1 that is the increased propensity for errors made by new junior staff, being the subject of perennial worry in the USA.

For all the interest, the evidence to support such concerns was, until very recently, patchy. Although studies repeatedly failed to find a statistically increased risk of mortality, trends were still detected towards increased surgical complication rates,2 anaesthetic errors,3 increased length of stay and higher utilisation of services early in the academic year.4,5 In 2005, a highly detailed study of over 700 US teaching hospitals demonstrated a small relative increase in mortality early in the academic year.5 This finding was confirmed in the work of Jen et al, who used hospital episode statistics to retrospectively examine cohorts of emergency admissions in England between 2000 and 2008.6 Patients admitted on the first Wednesday in August, the traditional changeover day in the UK, were found to have a higher early death rate than those patients admitted on the previous Wednesday. This effect was more pronounced for those with a primary medical diagnosis.

The finding of increased mortality in the UK during the August transition parallels the deepening disquiet induced by successive reforms of junior doctor working and training, such as the European Working Time Directive and Modernising Medical Careers, and the conclusions of recent reports by Tooke7 and Collins,8 which suggest that junior doctors are unprepared for the rigors of pre-registration work.

This survey sought to explore the views of doctors in the UK on the impact of junior doctor changeover on patient safety and hospital functioning and to assess the level of support for the different options that have been proposed to improve patient care, reduce inefficiency and provide a better experience for junior doctors.

Methods

The survey was conducted using a 19-item online questionnaire, constructed by a Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (RCPE) working group and revised by the RCPE Council. A hyperlink to the survey was sent out by email to 3,784 RCPE fellows and members resident in the UK, and to approximately 600 Society of Acute Medicine (SAM) medical members in mid-December 2009. A reminder was sent after two weeks and the survey closed after five weeks. The results were collated by a senior fellow of the RCPE.

Results

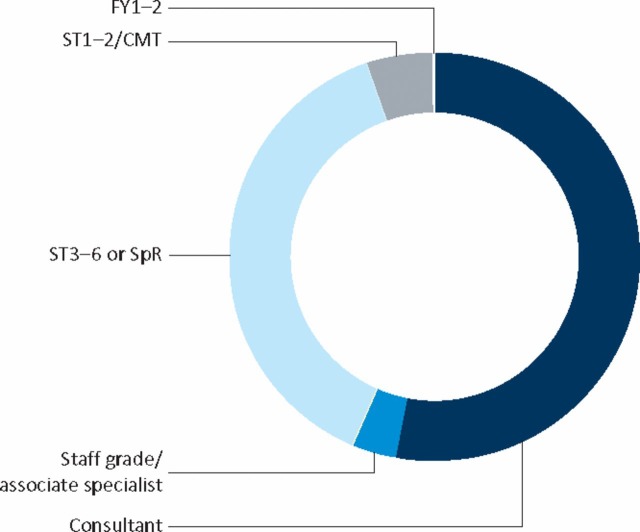

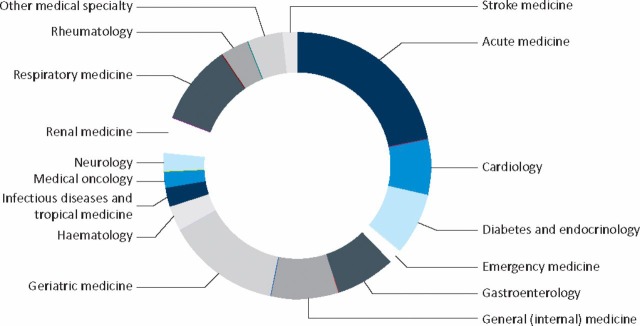

The survey received 763 responses (estimated response from both organizations ∼20%); distribution by grade is shown in Fig 1. The majority of respondents (82.7%) were working in specialties which traditionally contribute heavily to the care of emergency medical admissions (Fig 2). In total, 125/721 respondents indicated that their specialty was in other disciplines, including paediatrics (1.5%), palliative care (1.5%) and psychiatry (0.4%). Respondents were primarily from Scotland (38.9%) and the North of England (27.2%); the remaining respondents were relatively equally spread among the other UK deaneries (2.2–5.7%) with the exceptions of Oxford (1.1%) and Kent, Surrey and Sussex (0.8%).

Fig 1.

Distribution of respondents by grade. CMT = core medical training; FY = foundation year; SpR = specialist registrar; ST = specialty training.

Fig 2.

Distribution of respondents working in adult medical specialties.

Impact of transition

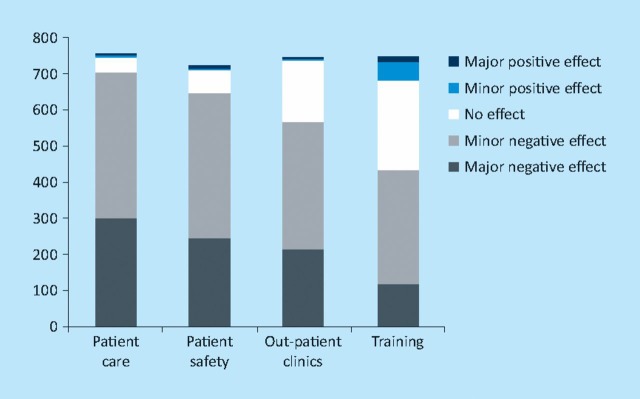

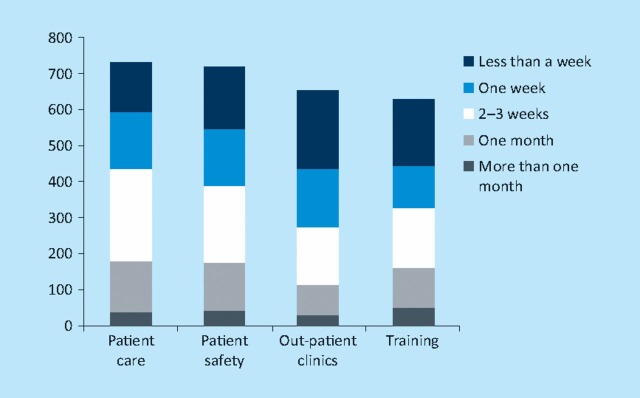

Of respondents, 93.3% estimated that 50–100% of the trainees at their hospital changed over on the same day, with over 90% rating the impact on patient care and patient safety as negative (Fig 3). The impact was considered to be less on outpatient clinics and training. The effects on all aspects of care and training were felt to last for up to one month (Fig 4). Of respondents, 35.3% reported that their institutions cancelled outpatient clinics or day case procedures. In total, 32.6% responded that no additional cover was provided in their institution; where cover was arranged, this was primarily provided by consultant (62.1%) and staff grade (35.5%) doctors.

Fig 3.

Perceived impact of the August Transition on hospital functioning and junior medical staff training.

Fig 4.

Length of perceived impact of the August Transition on hospital functioning and junior medical staff training,

Changeover

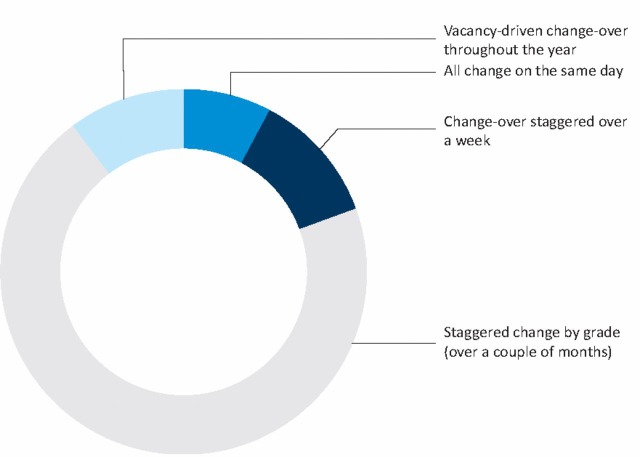

Attitudes towards timing of transition are indicated in Fig 5. Only 7.7% of respondents felt that changeover should continue to take place on a single day.

Fig 5.

Preferences by type of transition.

Shadowing

Of all respondents, 84.5% believed that shadowing was either ‘very effective’ (29.6%) or ‘effective’ (54.9%) as a means of induction. Half of all respondents reported that the current recommended time for shadowing prior to commencing work is one to two weeks, with 10.5% reporting shadowing placements of four or more weeks. Of respondents, 74.1% felt that shadowing should be used further to aid induction.

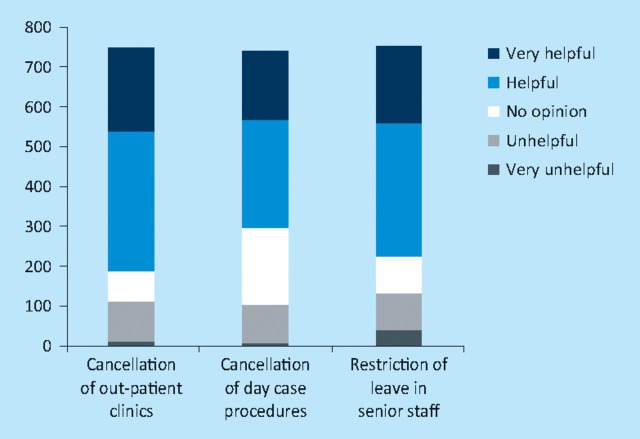

Changes to consultant practice

Changes in consultant work practices that were perceived as being beneficial are outlined in Fig 6. In total, 75% of respondents thought that cancellation of outpatient clinics was helpful, as was cancellation of day case procedures and restriction of leave for senior staff.

Fig 6.

Changes to consultant work practices perceived to be beneficial during the August Transition.

Use of online induction

Of respondents, 26.3% reported that their deanery used an online induction programme. Of those using this facility, 50.9% rated the induction as ‘very effective’ (1.8%) or ‘effective’ (49.1%), with 49.1% rating it as ‘ineffective’ or ‘very ineffective’. In total, 50.2% described the balance of their induction programme as a ‘balance of clinical/non-clinical’, with 5.1% describing it as ‘mainly clinical’. Thirty-seven per cent thought that further use of online induction would be beneficial.

Discussion

There was almost a universal perception that the August transition compromises patient safety and patient care, with inadequate measures in place at the local level to support junior staff in their induction or to ensure clinical safety. As one respondent summarised, ‘August is always a nightmare’. Two strong themes emerged with regard to change: structured change to the system, at national and institutional levels and better preparation of medical students for the transition, both by medical schools and employing institutions. Concomitantly, there was enthusiasm for consultant medical staff not only facilitating, but leading any such changes.

Of the solutions posited for structured changes, moving to a staggered transition by grade received most support, with over 80% responding favourably, with a preference for the changeover to occur by grade over a period of a month. Less than 10% wished to retain a single changeover day, but this was qualified as only being viable with staggered induction, stronger clinical leadership and clearer cover arrangements. Although there is no published evidence, several countries, including Australia and New Zealand, have a long tradition of staggered changeovers. And, although the question was not directly asked, the virtually unanimous view of the comments was that the transition should be moved out of August entirely, thus eliminating conflict with holiday periods. Although there was majority support for the reorganisation of consultant duties, the comments highlighted the limited utility of using consultant staff to pick up the ‘clinical slack’ generated by the absence of junior staff. By contrast, the literature points to an alternative role for consultants during this difficult period by providing direct support and advice to vulnerable junior staff. The frustrations and anxiety of the transition can be ameliorated by rapid integration of juniors into teams, clear delineation of roles and early constructive feedback from senior colleagues.9–11 While the temptation may be to use consultant staff to fill gaps left in the rota or save costs on locum staff, there is a much stronger case to be made for clear and consistent clinical leadership in the early part of the transition.

With regard to the better preparedness of medical students, shadowing was strongly supported by respondents, who also advocated for longer periods of shadowing, rather than just the first one or two days of the August transition week. This strongly mirrors the views of medical students and junior doctors, who almost uniformly find shadowing to be more useful than the taught curriculum with regard to preparing for the real world of clinical practice,10 particularly when the shadowing is undertaken in the hospital where they later work as a house officer or when the student is allowed to effectively function as a junior doctor, rather than just clerking patients.9–11 Despite the General Medical Council (GMC) making shadowing a requirement of the final year of medical school,12 only a minority do so in their place of later employment.11 The GMC also recommends that shadowing students should be ‘protected’ from the ‘business’ of being a junior doctor, which the evidence suggests may be counterproductive.

Respondents were ambivalent about the utility of induction programmes. The comments from the survey were predominantly critical of the ability of induction programmes to prepare junior staff for work, citing a lack of information tailored for medical staff. This corresponds with research findings that junior staff highly prize pragmatic information10 and that longer, clinically-orientated inductions (of one to two weeks) seem to have a lasting effect on consolidating team structures.13 Respondents also complained about institutional issues relating to induction, such as poor organisation, lack of timeliness and difficulty in engaging multiple hospital departments. The grey literature supports the notion that online induction is attractive to junior staff14 and, anecdotally, it is easier to administer. However, the comments from the survey cited the high level of mandatory content, the inflexibility and lack of uniformity of many online tracking packages as barriers to their better use. Given the ubiquity of induction, this suggests that there is ample opportunity for well-constructed research and the need for better programme evaluation.

Free-text comments have not been reported in detail. These, however, highlighted the complexity of the issues of junior staffing and recent changes to training. Concerns were repeatedly expressed about the problems created by having a single entry point into training, with many citing difficulties in recruiting and retaining registrars in locum posts and others expressing anxiety about patient safety, continuity of care and the provision of adequate registrar induction. Several respondents indicated that their trusts provided little corporate induction, and others that even the better programmes were often rushed or poorly organised. The overall consensus was that the institutions involved in facilitating the transition all suffered from ‘corporate amnesia’, resulting in the need to ‘start from scratch’ every year.

Limitations

Due to the construct of the study there was a relatively disproportionate response from acute physicians to the survey. This likely reflects a good response from members of SAM. However, as acute physicians are increasingly responsible not only for the acute take, but the accompanying out-of-hours rostering of junior staff, they are well placed to comment on the disruption caused to the care of the unwell medical patient by the transition.

Conclusion

There is a clear and pressing need for planned change. The evidence for deterioration in the quality of patient care during the August transition is mounting and the opinions expressed in this survey point to a system in urgent need of reform. This has been acknowledged at the national level, with the establishment of a Transition Group by Medical Education England and the Medical Schools Council. The question remains as to the timeliness and thoroughness of any proposed reforms. The results of the survey would suggest that the key would be to move to a staggered transition period in any month other than August. Ideally, such a change should also mandate longer contracts, with pre-registration doctors being paid for at least a full week of shadowing and induction. This would have cost implications at a time of budgetary restraint, but this would be balanced by less disruption to service and safer patient care. In the meantime, hospitals need to approach the August transition as a ‘whole hospital’ problem, rather than as one that can be fixed by consultants taking over the duties of junior doctors. There should be more emphasis on the provision of high quality induction, ideally shaped to the needs of local services. There is an argument for the provision of national accreditation of aspects of mandatory training specifically tailored to junior doctors, such as information governance, and to provide this via alternatives to face-to-face lectures (eg online, DVD, podcast).

While other authors have pointed to more complex, local solutions for ensuring patient safety at the time of transition,15 the evidence suggests those options supported by the survey would have a positive impact on patient safety, hospital functioning and staff satisfaction. The doctors surveyed have indicated that not only is there an appetite for change, but the desire to enthusiastically lead and support it. All that is lacking now is the political will.

References

- 1.Buchwald D, Komaroff AL, Cook EF, Epstein AM. Indirect costs for medical education. Is there a July phenomenon? Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:765–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inaba K, Recinos G, Teixeira PG, et al. Complications and death at the start of the new academic year: is there a July phenomenon? J Trauma. 2010;68:19–22. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181b88dfe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haller G, Myles PS, Taffé P, Pernegger TV, Wu CL. Rate of undesirable events at the beginning of the academic year: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b3974. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rich ED, Hillson SD, Dowd B, Morris N. Speciality differences in the ‘July phenomenon’ for Twin Cities teaching hospitals. Med Care. 1993;31:73–83. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huckman RS, Barro JR. Cohort turnover and productivity: the July phenomenon in teaching hospitals. Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research. 2005. NBER Working Paper No. 11182 www.nber.org/papers/w11182.

- 6.Jen MH, Bottle A, Majeed A, Bell D, Aylin P. Early in-hospital mortality following trainee doctors' first day at work. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tooke J. Aspiring to excellence. Findings and final recommendations of the independent inquiry into Modernising Medical Careers. London: MMC Inquiry; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins J. Foundation for excellence. An evaluation of the Foundation Programme. London: Medical Education England; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matheson C, Matheson D. How well prepared are medical students for their first year as doctors? The views of consultants and specialist registrars in two teaching hospitals. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:582–9. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.071639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matheson CB, Matheson DJ, Saunders JH, Howarth C. The view of doctors in their first year of medical practice on the lasting impact of a preparation for house officer course they undertook as final year medical students. BMC Med Ed. 2010;10:48. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cave J, Woolf K, Jones A, Dacre J. Easing the transition from student to doctor: how medical can schools help prepare their graduates for starting work? Med Teach. 2009;31:403–8. doi: 10.1080/01421590802348127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.General Medical Council. Tomorrow's doctors. London: GMC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosemary I, Bell DA, Jayathissa SK. Clinical orientation programme for new medical registrars–a qualitative evaluation. Aust Health Rev. 2009;33:57–61. doi: 10.1071/ah090057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James J, Bibb S, Walker S. Tell it how it is. 2008. Summary research report. Talentsmoothie, www.talentsmoothie.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/TIHIS-report-Summary-and-Conclusion.pdf. [DOI]

- 15.Barach P, Johnson JK. Reducing variation in adverse events during the academic year. BMJ. 2009;339:b3949. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]