Abstract

There is considerable controversy concerning the benefits and risks of oxygen treatment in many situations and healthcare professionals receive conflicting advice about safe oxygen use. The British Thoracic Society (BTS) has published up-to-date, evidence-based guidelines for emergency oxygen use in the UK in order to encourage the safe use of oxygen in emergency situations and improve consistency of clinical practice.1 The purpose of this concise guideline is to summarise the key recommendations, particularly concerning emergency oxygen use in the hospital setting.

Key Words: hypercapnic respiratory failure, hypoxaemia, oxygen

Background

Oxygen is probably the most common drug to be used in the care of patients who present with medical emergencies; approximately 34% of ambulance journeys involve oxygen use at some stage and national audit data suggest that 18% of hospital inpatients in the UK are being treated with oxygen at any given time.2,3

At present, oxygen is administered for three main indications:

to correct hypoxaemia, as there is good evidence that severe hypoxaemia is harmful

to prevent hypoxaemia in unwell patients

to alleviate breathlessness.

Only the first of these indications is evidence based. Recent evidence suggests that the administration of oxygen to prevent hypoxaemia in ill patients may actually place them at increased risk if severe hypoxaemia does actually develop.1 Additionally, there is no evidence that oxygen relieves breathlessness in non-hypoxaemic patients and there is evidence for lack of effectiveness in non-hypoxaemic breathless patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or advanced cancer. However, patients at risk of hypoxaemia should be adequately monitored in an appropriate clinical setting.

Most clinicians who deal with medical emergencies will encounter adverse incidents and occasional deaths due to underuse and overuse of oxygen.1,4 Audits of oxygen use and oxygen prescription have shown consistently poor performances in many countries.1 There is considerable controversy concerning the benefits and risks of oxygen treatment in virtually all situations where oxygen is used and, as such, healthcare professionals receive conflicting advice about safe oxygen use. Unfortunately, this is an area of medicine where there are many strongly-held beliefs but very few randomised controlled trials.

Previous UK guidelines on emergency oxygen therapy were published in 2001 by the North West Oxygen Group, based on a systematic literature review.5 Against this background the Standards of Care Committee of the British Thoracic Society (BTS) established a working party in association with 21 other societies and royal colleges to produce an evidence-based and up-to-date guideline for emergency oxygen use in the UK. Information in this concise guidance document has been extracted from the full BTS guideline.1 A full description of the methodology may be found in BTS guideline document. The levels of evidence and grades of recommendation are based on those used by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.6

Aims of the guideline

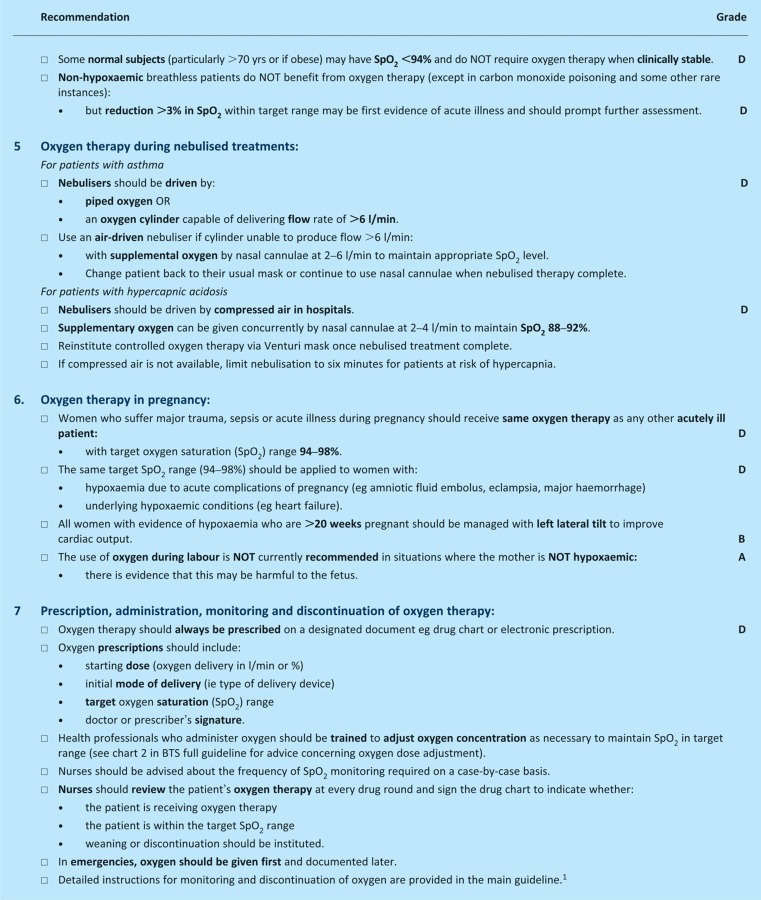

The guideline covers the safe prescription and administration of emergency oxygen to all patients. This concise guidance document provides a summary of the key recommendations detailed in the full BTS guideline.1 It is intended for use by all healthcare professionals who may be involved in emergency oxygen use, but focuses on use in the general hospital setting (excluding intensive care units and other specialised units). Please refer to the full guideline for specific recommendations on the use of oxygen in the primary care and ambulance settings.

Limitations of the guideline

The recommendations are based on the best available evidence concerning oxygen therapy. However, a guideline can never be a substitute for clinical judgement in individual cases. There may be cases where it is appropriate for clinicians to act outside of the advice contained in this guideline because of the needs of individual patients or practical concerns, such as ward staffing levels or the availability of appropriate monitoring equipment.

The responsibility for the care of individual patients rests with the clinician in charge of the patient's care and the advice offered in this guideline should not be relied upon as the only source of advice in the treatment of individual patients.

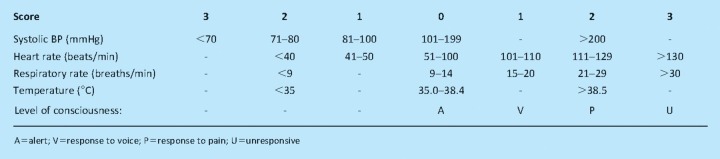

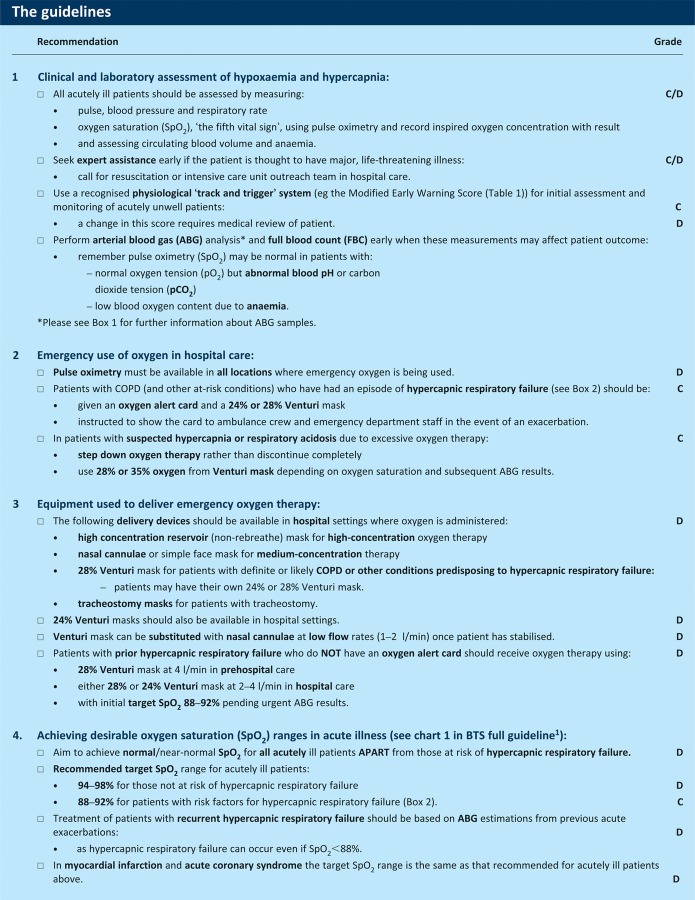

Table 1.

Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS).

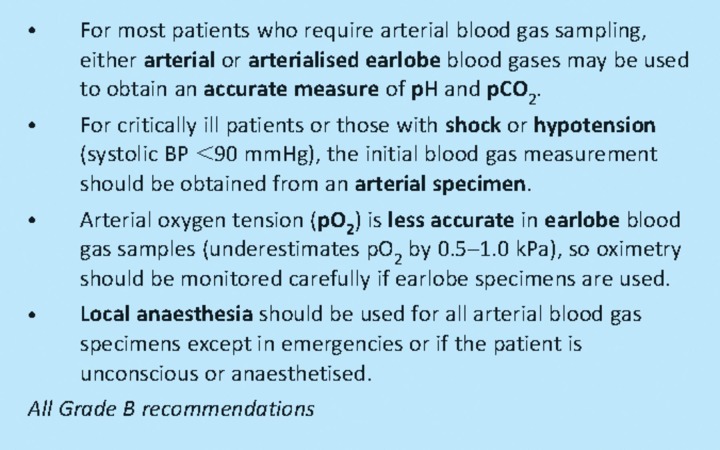

Box 1. Arterial and arterialised blood gases.

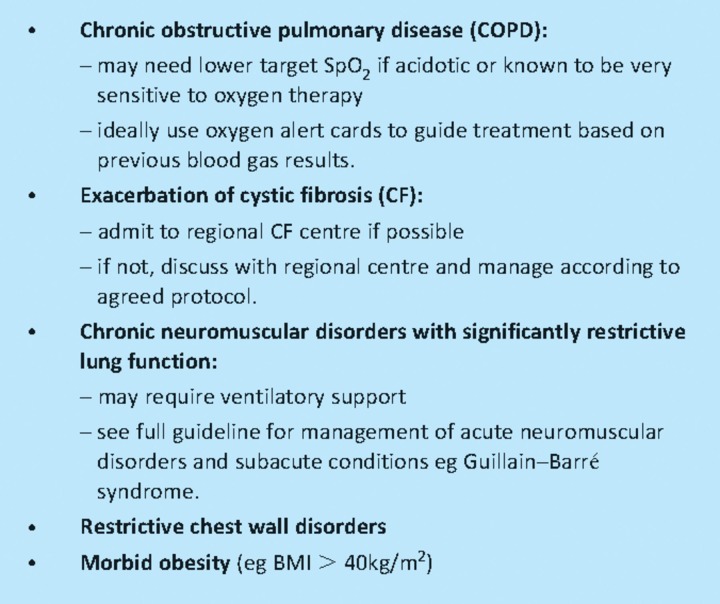

Box 2. Conditions associated with elevated risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure requiring controlled or low-concentration oxygen therapy (target range usually 88–92%).

This guideline gives very little specific advice about the management of many medical conditions that may cause hypoxaemia (apart from the specific issue of managing the patient's hypoxaemia). Readers are referred to other guidelines for advice on the management of specific conditions, eg COPD, pneumonia, heart failure, where slightly different approaches to emergency oxygen therapy may be suggested. The present guideline aims to provide simple all-embracing advice.

Implications and implementation

In order to implement the guideline recommendations, all organisations involved in administering emergency oxygen will need to develop new oxygen policies. The BTS has identified oxygen champions in all acute hospitals to help implement the changes.

The UK Ambulance Service updated their policies to implement the guideline principles in 2009. The BTS is undertaking annual audits across all acute hospitals and the results of the audits can be taken back to ward level.3 It is anticipated that this will aid implementation of the guideline.

References

- 1.O'Driscoll BR, Howard LS, Davison AG. BTS guideline for emergency oxygen use in adult patients. Thorax. 2008;63(Suppl 6):vi1–68. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.102947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hale KE, Gavin C, O'Driscoll BR. Audit of oxygen use in emergency ambulances and in a hospital emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:773–6. doi: 10.1136/emj.2008.059287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Driscoll BR, Howard LS, Bucknall C, Welham SA, Davison AG. On behalf of the British Thoracic Society. British Thoracic Society emergency oxygen audits. Thorax. 2011 Apr 17 doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200078. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Patient Safety Agency. Oxygen safety in hospitals, in Rapid Response Report. London: NPSA; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy R, Mackway-Jones K, Sammy I, et al. Emergency oxygen therapy for the breathless patient. Guidelines prepared by North West Oxygen Group. Emerg Med J. 2001;18:421–3. doi: 10.1136/emj.18.6.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Clinical Guideline Centre. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. London: NCGC; 2010. [Google Scholar]