Frailty (Latin: fragilita; brittleness) is an important but incompletely understood clinical concept in geriatric medicine. There is no internationally agreed definition, but a consensus view is emerging1 in which the phenotype of frailty is considered to develop as a consequence of a decline in several physiological systems which collectively results in a vulnerability to sudden health state changes triggered by relatively minor stressor events.

Pathophysiology of frailty

Age-related changes to multiple physiological systems are fundamental to the development of frailty, particularly the neuromuscular, neuroendocrine and immunological systems.2 These changes interact cumulatively and detrimentally, resulting in a decline in physiological function and reserve. When a cumulative threshold is reached, the ability of an individual to resist minor stressors and maintain physiological homeostasis is compromised. The loss of functional homeostatic reserve at the level of individual physiological systems can ultimately adversely affect the whole person.3 On the basis of the resulting frailty phenotype, it is possible to identify older people who are frail. Such people are predisposed to adverse health consequences, particularly falls and delirium, following relatively minor stressor events. The phenotype includes:

sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass and strength)

anorexia

osteoporosis

fatigue

risk of falls

poor physical health.3

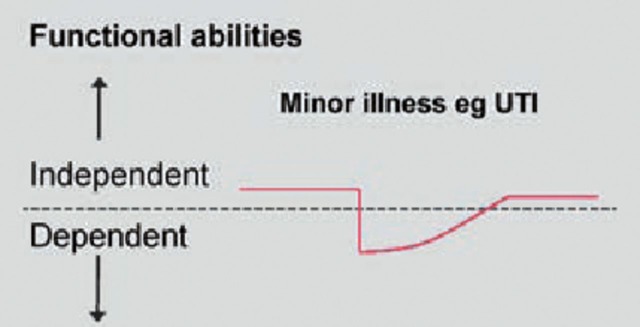

The loss of functional homeostatic reserve is shown diagrammatically in Fig 1. This illustrates a person who is functionally independent but, through the combined processes of ageing, chronic diseases and deconditioning, is so close to a theoretical line of decompensation that a small additional deterioration caused by a minor stressor event (commonly a urinary infection, new medication prescription etc) results in a sudden and disproportionately severe health state change from one of independence to one of dependence.

Fig 1.

Vulnerability to sudden change in health state due to reduced functional reserve in frail older people. UTI = urinary tract infection

The addition of a minor stressor event to a frail older person with impairment of balance or cognition explains conceptually the clinical syndromes of falls and delirium, respectively, as common consequences of frailty. Healthcare systems struggle to cope adequately with these common presentations of ill health in older people who are frail mainly because their healthcare states change suddenly and unpredictably. This is the basis of comprehensive geriatric assessment which has been demonstrated to optimise outcomes for older people with frailty.4

The frailty cycle

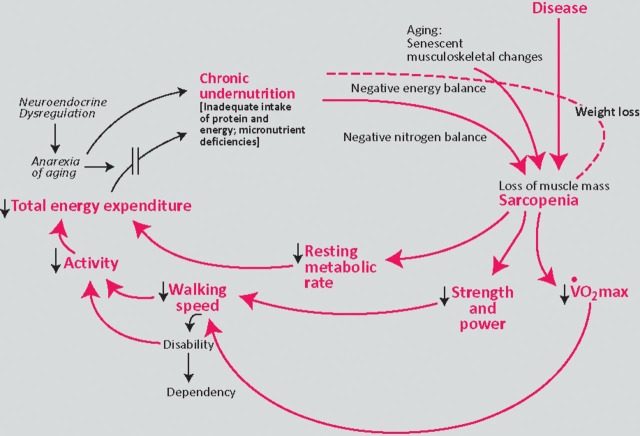

The key interacting processes that promote the development of frailty are summarised in Fig 2. These interactions result in a self-perpetuating frailty ‘cycle’ or ‘spiral’2 whereby increasing frailty gives rise to increased risk of further decline towards disability and greater frailty.

Fig 2.

The frailty cycle VO2 = volume of oxygen utilisation. Reproduced with permission from The McGraw-Hill Companies.

Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia is a key component of frailty, characterised by progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength.5 The syndrome of sarcopenia can result when there is loss of physiological reserve in the neuromuscular system. A complex relationship between muscle fibre loss, muscle fibre atrophy and multiple contributory factors (including nutritional, hormonal, metabolic and immunological) is proposed to contribute to the development of sarcopenia.6

Observational studies have reported loss of muscle strength between 1–3% per annum in older people, with even greater losses observed in the oldest old.6 The development of sarcopenia can adversely affect the ability of an older person to remain functionally independent. Muscle strength is required for the critical basic mobility skills of getting out of bed, standing up from a chair, walking a short distance and getting off the toilet.7 When the ability to perform these critical skills is impaired, an older person is at risk of becoming dependent for care needs.

Detection of frailty

The Fried frailty model

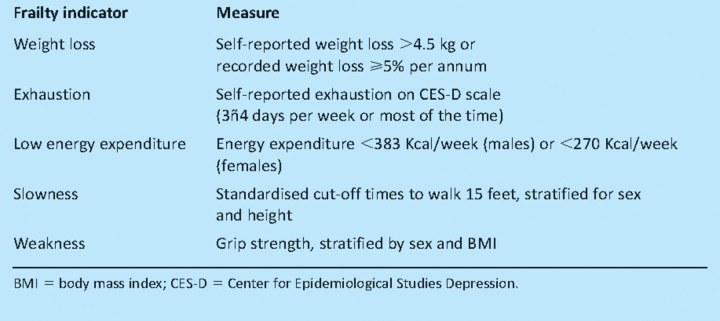

Fried et al operationalised the core components of the frailty cycle to describe a clinically recognisable phenotype.8 When the identified five key components (and their operationalised indicators) are present in combination they have the potential to interact and cause a ‘critical mass’ that comprises the frailty syndrome (Table 1). Although the individual items of the Fried model of frailty are identifiable to clinicians, the precise and objective measurement of the five domains is more complex and more appropriate to research studies than for routine clinical care.

Table 1.

The five Fried model indicators of frailty and their associated measures.

People with none of the five indicators are characterised as robust older people. Those with one or two indicators are hypothesised to comprise an ‘intermediate’ or pre-frail group, while people with three or more indicators are considered to be frail. Importantly, older people who scored less than 18 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (ie with moderate/severe cognitive impairment) were excluded from the cohort in which the Fried model of frailty was developed. There is therefore some uncertainty about the relationship between frailty, cognitive impairment and dementia.

The Edmonton frail scale

The Edmonton frail scale (EFS) is a diagnostic tool designed to identify frail older people in clinical settings.9 It requires less than five miutes to administer and is valid and reliable when performed by a non-specialist. The Reported EFS has been developed more recently to measure frailty in an acute hospital inpatient setting.10

The epidemiology of frailty

A recent UK study investigated the prevalence of frailty among 638 community-dwelling people aged 64–74 years,11 using operationalised criteria based on the Fried frailty model to define its presence. The frailty prevalence rates found were 8.5% for women and 4.1% for men. Using data from the US Cardiovascular Health Study, the Fried investigators recorded a frailty prevalence of 6.9% in a cohort of 5,201 men and women aged 65 years or above.8 The prevalence of frailty increased with age, with rates of 3.2%, 9.5% and 25.7% for age groups 65–70, 75–79 and 85–89 years, respectively. The three-year frailty incidence rate was 7%, with a further 7% between years 4 and 7.

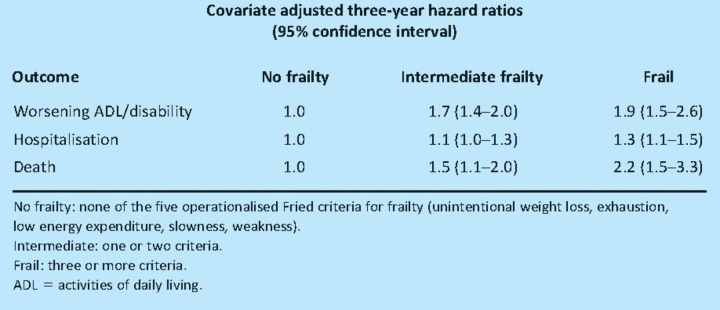

Frailty is associated with important adverse health consequences. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for 15 covariates including age, gender, cognitive function, activity restriction, self-reported health and depression, older people defined as being frail on the basis of the Fried criteria were at significantly increased risk of disability, hospitalisation and death (Table 2).8

Table 2.

Three-year covariate adjusted outcome data for older people, categorised on the basis of five operationalised criteria.8

Key Points

Frailty is an important and common clinical condition characterised by a vulnerability to health state change following minor stressor events

Age-related changes to multiple physiological systems are fundamental to the development of frailty

Identifiable characteristics of the frailty phenotype include sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass and strength), anorexia, osteoporosis, fatigue, risk of falls and poor physical health

Frailty is associated with important adverse health outcomes, including increase in the risks of disability in older age and of admission to long-term care and increased mortality

Interventions that limit the progression of frailty have the potential to prevent disability in older age, and thereby the potential to improve general health and well-being

Frailty, disability and comorbidity

The relationship between frailty, disability and comorbidity (defined as the presence of two or more chronic diseases) is complex. There is emerging agreement that, while frailty, disability and comorbidity are closely related and exhibit significant overlap, they are not synonymous.12 Therefore, as frailty develops with multisystem physiological decline, it is possible that an individual may be phenotypically and measurably frail in the absence of comorbidity. However, the effects of a single severe disease, the presence of subclinical disease or the presence of undiagnosed disease add further complexity.

Disability in older age can be measured using standardised instruments that assess activities of daily living, for example the Barthel Index.13 Such disability can develop progressively (eg as a result of frailty) or catastrophically (eg as a result of stroke or hip fracture). Results from a cohort of 6,640 older people suggest that approximately 50% of disability in older age develops progressively and 50% develops catastrophically.14 The contribution of physiological frailty to the development of disability in older age is likely to be significant.

Can frailty be treated?

The association between frailty and adverse health outcomes carries significant health resource implications. Social care expenditure for older people in the UK is projected to rise from $5.9 billion in 2006 to $13.4 billion in 2026.15 Therefore any reduction in the prevalence or severity of frailty is likely to have large benefits for the individual, their family and society.

Interventions

Sarcopenia and chronic undernutrition accompany frailty and are natural targets for treatment.

Physical activity. Interventions, particularly those involving strength and balance training, have been successful at improving muscle strength and functional abilities in frail people. A recent systematic review reported a synthesis of 49 randomised controlled trials involving physical rehabilitation for older people in permanent long-term care (reasonably assumed to be a frail population).16 The study concluded that there is good evidence that individual or group exercise programmes are both acceptable and effective in improving mobility and other daily living tasks in this vulnerable population. Physical activity interventions targeted at improving the functional status of frail older people living in the community have also been successful.17

Nutrition. Nutritional interventions appear to be less effective. When combined with physical activity interventions, nutritional supplementation does not appear to be independently effective at improving functional abilities of frail older people compared to the former alone.18

Pharmacological. Several pharmacological agents, including anabolic steroids, statins and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, have actions and effects with the potential to limit the development and progression of frailty. However, evidence of a beneficial effect from these agents has not yet been reliably demonstrated.1

Conclusions

Frailty is an important and common clinical condition associated with significant adverse health outcomes, including the development of disability in older age with its attendant personal and societal costs. Common manifestations of frailty include falls and delirium. Physical activity interventions that limit the progression of frailty have the potential to prevent disability in older age, and thereby the potential to improve general health and well-being.

References

- 1.Walston J, Hadley EC, Ferrucci L, et al. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:991–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried L, Walston J. Frailty and failure to thrive. In: Hazzard W, Blass J, Halter J, et al., editors. Principles of geriatric medicine and gerontology. 5th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strandberg TE, Pitkälä KH. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2007;369:1328–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60613-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, Adams J, Rubenstein LZ. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Lancet. 1993;342:1032–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92884-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al. European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39:412–23. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doherty TJ. Invited review: aging and sarcopenia. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1717–27. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00347.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isaacs B. Clinical and laboratory studies of falls in old people. Prospects for prevention. Clin Geriatr Med. 1985;1:513–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–56. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Tahir A, Rockwood K. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing. 2006;35:526–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilmer SN, Perera V, Mitchell S, et al. The assessment of frailty in older people in acute care. Australas J Ageing. 2009;28:182–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syddall H, Roberts HC, Evandrou M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of frailty among community-dwelling older men and women: findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Age Ageing. 2010;39:197–203. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:255–63. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.M255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Simonsick E, et al. Progressive versus catastrophic disability: a longitudinal view of the disablement process. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51:M123–30. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51A.3.M123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poole T. Funding adult social care in England. London: The Kings Fund; 2009. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forster A, Lambley R, Young JB. Is physical rehabilitation for older people in long-term care effective? Findings from a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2010;39:169–75. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill TM, Baker DI, Gottschalk M, et al. A programme to prevent functional decline in physically frail, elderly persons who live at home. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1068–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiatarone MA, O'Neill EF, Ryan ND, et al. Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1769–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406233302501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]