Abstract

Oncolytic viruses (OVs) are a versatile new class of therapeutic agents based on native or genetically modified viruses that selectively replicate in tumor cells and can express therapeutic transgenes designed to target cells within the tumor microenvironment and/or host immunity. To date, however, confirmation of the underlying mechanism of action and an understanding of innate and acquired drug resistance for most OVs have been limited. In this issue of the JCI, Zamarin et al. report a comprehensive analysis of an oncolytic Newcastle disease virus (NDV) using both murine melanoma tumor models and human tumor explants to explore how the virus promotes tumor eradication and details of the mechanisms involved. These findings have implications for the optimization of oncolytic immunotherapy, at least that based on NDV, and further confirm that specific combinatorial approaches are promising for clinical development.

Oncolytic immunotherapy in the treatment of cancer

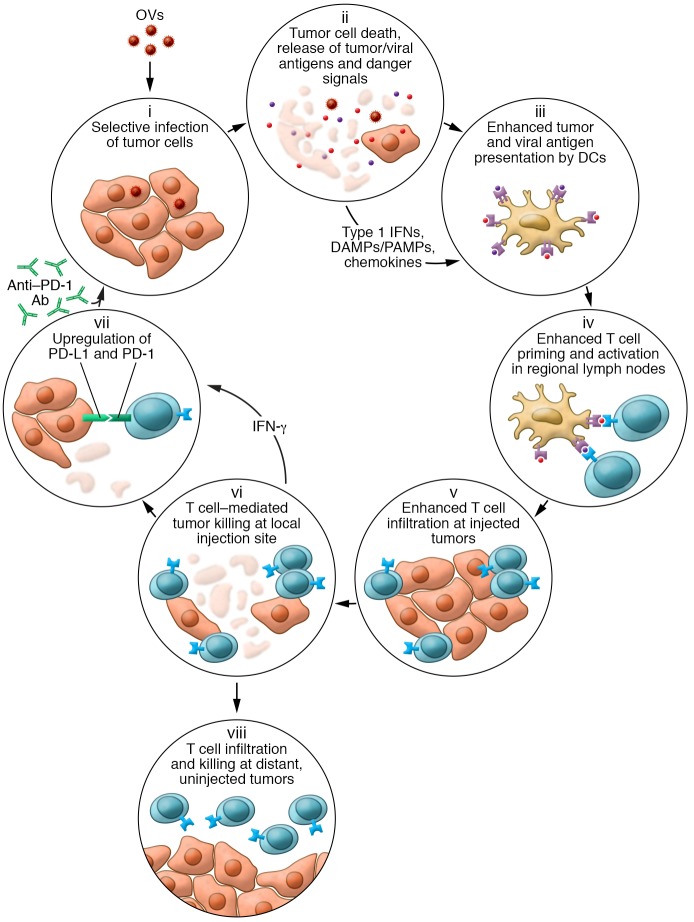

Oncolytic immunotherapy is a new approach to cancer treatment that utilizes oncolytic viruses (OVs) either by themselves or as part of a combination regimen. OVs mediate antitumor activity through several independent mechanisms, including direct immunogenic cell death and induction of host antitumor immunity, thereby correcting multiple aspects of the cancer-immunity cycle that may be dysfunctional in patients with established tumors (Figure 1). Cancer treatment with OVs takes advantage of the immunogenicity of the virus and the ability to manipulate host immune responses through their use. Thus, in addition to killing injected tumors, OVs can induce the regression of distant, uninjected tumors, which is thought to occur through the generation of antigen-specific antitumor immune responses, including tumor neoantigens. These “abscopal” responses may allow injection of only a subset of the most accessible tumors in a patient but result in the rejection and continuous protection against distant, more difficult-to-access tumors (1). Further, OV activity is probably influenced by the viral species used, the influence of any transgenes encoded within the virus, the type of tumor targeted, host immune polymorphisms, and the status of the host-tumor immune response at the time of treatment.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of how OVs influence various aspects of the cancer-immunity cycle.

Following tumor infection by an OV, the virus selectively replicates in tumors cells (i). The cells are lysed, resulting in immunogenic cell death and release of soluble virus- and tumor-specific antigens, danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), type 1 IFNs, and chemokines (ii), which help recruit and condition professional antigen-presenting cells such as DCs (iii). DCs migrate with antigen to regional lymph nodes, where they prime and activate virus- and tumor-specific T cells (iv). The chemokine gradient generated within the tumor microenvironment recruits antigen-specific T cells (v), and T cells mediate cytotoxic effector functions within the injected tumor (vi). The local cytokine profile can also increase PD-1 expression on T cells and PD-L1 expression on tumor cells (vii) as a counterregulatory measure, limiting immune responses but also rendering the tumors more susceptible to treatment with checkpoint blockade. In contrast to some intratumoral therapies, OVs can also result in trafficking of tumor-specific T cells to distant, uninjected tumors, where they can mediate antitumor activity (viii).

In this issue of the JCI, Zamarin et al. used both murine melanoma tumor models and human tumor explants to explore how the oncolytic Newcastle disease virus (NDV) promoted tumor eradication (2). They showed that while local intratumoral injection of either IFN-α or oncolytic NDV alone was able to mediate delayed tumor growth of injected lesions, only NDV was able to mediate the rejection of distant uninjected tumors. Additionally, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were recruited to distant tumors only with the OV treatment. The investigators also found increased gene expression related to T cell activation within the tumor microenvironment of both injected and uninjected lesions, but not in the spleen. These data suggest that OV therapy is tumor specific and might not act via nonspecific inflammatory responses that may be critical to other local intratumoral strategies.

Mechanism of oncolytic immunotherapy in a NDV model

Zamarin et al. also reported an increase in PD-L1 expression early after treatment in injected tumors, but late in contralateral flank tumors not injected with NDV. They went on to show that PD-L1 expression in the injected tumors was related to type 1 IFN production induced by the antiviral machinery within the injected tumors. This is a pathophysiologic response to early viral infection, in which local IFN is expected to induce expression of dynamic immune checkpoints such as PD-L1. In contrast, not only did distant tumors not show higher levels of PD-L1 until later in the course of treatment, but this increase was mediated by IFNs produced by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Further, PD-L1 expression in distant tumors was more common on infiltrating myeloid cells, with weak staining observed on tumor cells, suggesting that myeloid cells may be an important source of immune suppression in uninjected lesions. This is consistent with previous reports of talimogene laherparepvec (T-vec), an oncolytic herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) encoding granulocyte macrophage–CSF (GM-CSF) in melanoma patients, in which an increase in effector CD8+ T cells and a decrease in myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) was seen in injected tumors but not in distant tumors (3). These data not only suggest that PD-L1, and probably other immune checkpoints, can be a mechanism of tumor escape from single-agent OV therapy, but also highlight the potential to combine OVs with programmed cell death receptor 1/programmed death ligand 1–directed (PD-1/PD-L1–directed) agents. Indeed, there are already early data from clinical studies indicating particularly high response rates when T-vec is combined with pembrolizumab (4). In a small phase I study, 62% of melanoma patients had an objective response, with 33% showing complete regression of all tumors, and responses were associated with infiltration of lymphocytes and increased PD-L1 expression in the tumor. In a large randomized study, T-vec combined with ipilimumab demonstrated a doubling of responses compared with ipilimumab alone in patients with advanced melanoma, without an increase in toxicity (5).

Limitations of the study and concluding remarks

While the study by Zamarin et al. provides insights into how OVs mediate antitumor activity through different mechanistic pathways at injected and uninjected sites, it also has some important limitations. First, the study uses NDV, a small RNA virus, and the specific mechanism of its antitumor activity may differ as compared with that of other viruses, particularly large DNA viruses such as T-vec. While T-vec is the first OV to achieve FDA approval in cancer patients, a large number of other DNA and RNA viruses are also currently in active clinical development (1). Further studies are needed to show how each viral species mediates its antitumor activity. Additionally, the authors state that while they observed some degree of enhanced activity when combining NDV and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in mice, they reported a greater enhancement of activity by combining NDV and anti–cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (anti–CTLA-4). This may be a reflection of the tumor models selected for these experiments, the fact that NDV was used as the OV for these studies, or, more likely, the differences in murine and human host immune responses, in which CTLA-4 blockade may be more effective than PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition.

Overall, the article by Zamarin et al. highlights the complex and interesting biology involved in antitumor immunity induced through the use of OVs alone and in combination with checkpoint inhibition. The ability of OVs to interact with the host immune system provides a potent mechanism for manipulating the immune response to focus the immune effects on established cancers. In particular, it provides the opportunity to generate a truly patient-specific and potent antitumor vaccine through the activation of innate and adaptive immunity. The authors present compelling evidence suggesting that injected and uninjected tumors may respond through different mechanisms, at least with NDV. These insights further indicate that the combination of OVs and immune checkpoint inhibition may be particularly powerful, as already supported by recent early-phase clinical data (4, 5). In addition, the notable safety profile of OVs makes these agents highly attractive for inclusion in combination approaches in which an improved therapeutic window is desirable. Further studies on the detailed mechanisms of the antitumor activity of OVs in different settings such as anti–PD-1/PD-L1 resistance will be important to better understand how to optimize oncolytic immunotherapy and unleash the full potential of OVs.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Rob Coffin for useful comments and suggestions.

Version 1. 03/05/2018

Electronic publication

Version 2. 04/02/2018

Print issue publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: HLK is an employee of Replimune Inc.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2018;128(4):1258–1260. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI120303.

See the related article at PD-L1 in tumor microenvironment mediates resistance to oncolytic immunotherapy.

References

- 1.Kaufman HL, Kohlhapp FJ, Zloza A. Oncolytic viruses: a new class of immunotherapy drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14(9):642–662. doi: 10.1038/nrd4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zamarin D, et al. PD-L1 in tumor microenvironment mediates resistance to oncolytic immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(4):1413–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI98047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufman HL, Kim DW, DeRaffele G, Mitcham J, Coffin RS, Kim-Schulze S. Local and distant immunity induced by intralesional vaccination with an oncolytic herpes virus encoding GM-CSF in patients with stage IIIc and IV melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(3):718–730. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribas A, et al. Oncolytic virotherapy promotes intratumoral T cell infiltration and improves anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;170(6):1109–1119.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chesney J, et al. Randomized, open-label phase 2 study evaluating the efficacy and safety of Talimogene laherparepvec in combination with ipilimumab in patients with advanced, unresectable melanoma. J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7379. [published online ahead of print October 5, 2017]. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]