Abstract

Conflicting results identifying the association between tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke have been reported. Therefore, a dose-response meta-analysis was performed to clarify and quantitatively assess the correlation between tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke risk. Up to March 2017, seventeen cohort studies were included in current meta-analysis, involving a total of 879084 participants with 43750 incident cases. Our results showed statistically significant increment association between tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke risk. Subgroups analysis indicated that tooth loss was associated with a significant risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke in Asia and Caucasian. Furthermore, tooth loss was associated with a significant risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke in fatal cases and nonfatal cases. Additionally, a significant dose-response relationship was observed between tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke risk. Increasing per 2 of tooth loss was associated with a 3% increment of coronary heart disease risk; increasing per 2 of tooth loss was associated with a 3% increment of stroke risk. Subgroup meta-analyses in study design, study quality, number of participants and number of cases showed consistent findings. No publication bias was observed in this meta-analysis. Considering these promising results, tooth loss might provide harmful health benefits.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease affects millions of people in developed and developing countries that is now a public health crisis. Despite the decline in the mortality rate of developed countries, cardiovascular disease is still the main cause of death and has caused serious social and economic distress on a global scale over the past few decades. In low and middle-income countries, the incidence of cardiovascular disease has risen sharply [1–3]. By 2020, cardiovascular disease is expected to be the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in most developing countries[4]. The etiology of cardiovascular disease involves both genetic and environmental factors. Therefore, understanding the impact of environmental factors on cardiovascular disease will help to prevent cardiovascular disease.

Oral cavity is an important part of the body, and is starts in digestive system, mainly by the lip and cheek, tongue and palate, salivary glands, teeth and jaw, with mastication, swallowing, speech and feeling, and other functions, which maintain the normal shape of maxillofacial. Oral health is an important part of human health. The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies dental health as one of the top ten criteria for human health. Poor oral health may increase systemic inflammation, resulting in a local overly aggressive immune response, and thus could have important implications for cardiovascular disease. Periodontal disease and tooth loss are two common oral health measures[5]. Tooth loss has been considered to impact quality of life[6], and been known to considerably influence food choice, diet, nutrition intake, and esthetics[7].

Previous studies have examined the correlation between tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke risk[8–24]. However, the result remains controversial. Additionally, no study to clarify and quantitative assessed tooth loss in relation to tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke risk. Thus, we performed this dose-response meta-analysis to clarify and quantitative assessed the correlation between tooth loss and tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke risk.

Methods

Our meta-analysis was designed following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA Compliant) statement(S1 Checklist)[25].

Search strategy

PubMed and EMBASE were searched for studies that contained risk estimates for the outcomes of coronary heart disease and were published update to April 2017, with keywords including “Coronary heart disease” [MeSH] OR”stroke” [MeSH] OR “Cardiovascular Diseases” [MeSH] OR “Coronary Disease” [MeSH] OR “myocardial infarction” [MeSH] AND “dentition” [MeSH] OR”tooth loss” [MeSH] OR”edentulous” [MeSH]. The search strategy is shown in detail in S1 List.

Study selection

Two independent researchers investigate information the correlation between tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke risk: outcome was coronary heart disease and stroke. To ensure the correct identification of qualified research, the two researchers read the reports independently, and the disagreements were resolved through consensus by all of the authors.

Data extraction

Use standardized data collection tables to extract data. Each eligible article information was extracted by two independent researchers. We extracted the following information: first author; publication year; mean value of age; country; study name; sex; cases and participants; the categories of tooth loss; relative risk or odds ratio (OR). We collect the risk estimates with multivariable-adjusted[26]. According to the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, quality assessment was performed for non-randomized studies[27]. The disagreements were resolved through consensus by all of the authors.

Statistical analysis

We pooled relative risk estimates to measure the association between tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke risk; the hazard ratio were considered equivalent to the relative risk[28]. Results in different subgroups of tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke risk were treated as two separate reports.

Due to different definitions cut-off points in the included studies for categories, we performed a relative risk estimates by using the method recommended by Greenland, Longnecker and Orsini and colleagues[29]. A flexible meta-regression based on restricted cubic spline (RCS) function was used to fit the potential non-linear trend, and generalized least-square method was used to estimate the parameters. This procedure treats tooth loss (continuous data) as an independent variable and logRR of diseases as a dependent variable, with both tails of the curve restricted to linear. A P value is calculated for linear or non-linear by testing the null hypothesis that the coefficient of the second spline is equal to zero[29].

We use STATA software 12.0 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX, USA) to evaluate the relationships between tooth loss and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. By using Q test and I2 statistic to assess heterogeneity among studies. Random-effect model was chosen if PQ< 0.10 or I2>50%, otherwise, fixed-effect mode was applied. Begg’s and Egger’s tests were to assess the publication bias of each study. P< 0.05 was considered signifcant for all tests.

Results

A total of 2810 studies from Medline, 3246 studies from Embase. After removing duplicates study, 3028 studies were identifed. reviewing their titles and abstracts, 2978 citations were excluded. The remaining 50 citations were assessed in more detail for eligibility by reading the full text. Among them, 11 studies were excluded due to no relevant outcome measure; 15 studies were excluded due to no human studies; 3 study was excluded due to lack of detailed information; 4 study was excluded due to review; 1 study was excluded due to conference abstract. After review reference of studies, one article was identified. Finally, 28 studies were used for the final data synthesis. The flow chart of literature searching was presented in Fig 1.

Fig 1. Flow diagram of the study selection process.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies of tooth loss and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke are shown in the Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants in included studies of tooth loss in relation to risk of coronary heart disease and stroke.

| Author(year) | Study design | Country | Sex of population | Age at baseline (years) | No of participants | Endpoints (cases) | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietrich et al(2008) | Cohort | USA | Male | 21–84 | 1203 | Coronary Heart Disease(364) | 8 |

| Howell et al(2001) | Cohort | USA | Male | 40–84 | 22037 | Cardiovascular Disease(797) Stroke(631) |

8 |

| Hung et al(2004) | Cohort | USA | Male and Female | 40–75 | 41407 men 58974women |

Men Coronary Heart Disease(1656) Women Coronary Heart Disease(544) |

8 |

| Tuominen et al(2003) | Cohort | Finland | Male and Female | 30–69 | 2518 men 2392 women |

Men Coronary Heart Disease(566) Women Coronary Heart Disease(701) |

8 |

| Abnet et al(2005) | Cohort | China | Mix | 40–69 | 29584 | Cardiovascular Disease(1932) Stroke(2866) |

8 |

| Elter et al(2004) | Cohort | USA | Male | 52–75 | 8363 | Cardiovascular Disease(1619) | 8 |

| Holmlund et al(2010) | Cohort | Sweden | Male and Female | 20–89 | 7674 | Cardiovascular disease(299) Coronary heart disease(167) Stroke(83) |

7 |

| Hujoel et al(2000) | Cohort | USA | Mix | 25–74 | 8032 | Cardiovascular disease(1265) | 8 |

| Joshipura et al(1996) | Cohort | USA | Male | 40–75 | 44119 | Cardiovascular disease(757) | 8 |

| Joshy et al(2016) | Cohort | Australia | Mix | 45–75 | 172630 | Ischaemic heart disease(3239) Heart failure(212) Stroke(283) |

7 |

| Jung et al(2016) | Cohort | Korea | Mix | ≥50 | 5359 | Cardiovascular disease(536) | 7 |

| Liljestrand et al(2015) | Cohort | Finnish | Mix | 25–74 | 8446 | Cardiovascular disease(692) Coronary heart disease(482) Acutemyo cardial infarction(253) Stroke(268) |

8 |

| Noguchi et al(2015) | Cohort | Japan | Male | 36–59 | 3081 | Myocardial infarction | 8 |

| Schwahn et al(2013) | Cohort | Caucasian | Mix | 64.0 | 1803 | Cardiovascular disease(128) | 7 |

| Tu et al(2007) | Cohort | United Kingdom | Mix | ≤30 | 12223 | Cardiovascular disease(319) Coronary heart disease(222) Stroke(64) |

8 |

| Vedin et al(2015) | Cohort | Sweden | Mix | ≥60 | 15456 | Cardiovascular disease(705) Myocardial infarction(746) Stroke(301) |

8 |

| Watt et al(2012) | Cohort | Scotland | Mix | ≥40 | 12871 | Cardiovascular disease(297) Stroke(92) |

8 |

Table 2. Outcomes and covariates of included studies of tooth loss in relation to risk of coronary heart disease and stroke.

| Author(year) | Endpoints (cases) | Data source | Category and relative risk (95% CI) | Covariates in fully adjusted model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietrich et al(2008) | Coronary Heart Disease(364) | self-reports | Age <60 5 teeth lost, 1.0 (reference);7, 1.68 (1.13, 2.52); 10, 1.55 (0.94, 2.56);13, 2.12 (1.26, 3.60);Edentulous,1.90(0.92, 3.93) Age >60 6 teeth lost, 1.0 (reference);8, 0.90 (0.60, 1.35); 11, 1.13 (0.75, 1.69);17, 1.13(0.71, 1.78), Edentulous,1.95(1.18, 3.22) |

Adjusted for age, body mass index, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, triglycerides, hypertension, mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, smoking, alcohol intake, occupation and education, income, and marital status. |

| Hung et al(2004) | Coronary Heart Disease(1654) | self-reports | Men Nonfatal CHD <7 teeth lost, 1.0 (reference); >7-<15, 1.10 (0.95, 1.26);>16-<21, 1.35 (1.06, 1.72); >22, 1.36(1.11, 1.67) Fatal CHD <7 teeth lost, 1.0 (reference); >7-<15, 1.26 (1.01, 1.57);>16-<21, 1.19 (0.79, 1.80); >22, 1.79(1.34, 2.40) Women Nonfatal CHD <7 teeth lost, 1.0 (reference); >7-<15,1.14 (0.92, 1.42);>16-<21,1.34 (0.97, 1.87); >22, 1.64 (1.31, 2.05) Fatal CHD <7 teeth lost, 1.0 (reference); >7-<15, 1.02 (0.66, 1.55);>16-<21, 1.07 (0.56, 2.05); >22, 1.65 1.11,2.46) |

Adjusted for age, smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, physical activity, family history of myocardialinfarction, multivitamin supplementuse, vitaminE use, history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia in both cohorts and professionsfor men only, and for women only, menopausalstatusand hormoneuse |

| Joshipura et al(1996) | Cardiovascular disease(757) | self-reports | <7 teeth lost, 1.0 (reference); >7-<15, 1.03 (0.83, 1.27);>16-<21, 1.04 (0.71, 1.54); >22, 1.29(0.96, 1.73) | Adjusted for age; body mass index; exercise; smoking habits; alcohol consumption; family history of myocardial infarction before 60 years of age; vitamin E |

| Joshy et al(2016) | Ischaemic heart disease(3239) Heart failure(212) Stroke(283) |

self-reports | Ischaemic heart disease <10 teeth lost, 1.0 (reference); >10-<22, 1.05 (0.96, 1.15);>22-<31, 1.20 (1.06, 1.35); 32, 1.10(0.95, 1.26) Heart failure <10 teeth lost, 1.0 (reference); >10-<22, 1.50 (1.04, 2.18);>22-<31, 2.04 (1.35, 3.09); 32, 1.97(1.27, 3.07) Stroke <10 teeth lost, 1.0 (reference); >10-<22, 1.11 (0.72, 1.73);>22-<31, 0.90 (0.59, 1.40); 32, 1.20(0.90, 1.62) |

Adjusted for age; sex; tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, Australian born status, region of residence, education, health insurance, physical activity and body mass index, with missing values in covariates were coded as a separate categories. |

| Schwahn et al(2013) | Cardiovascular disease(128) | self-reports | 0 teeth lost, 1.0 (reference); >1-<9, 1.05 (0.67, 1.65);>10-<19, 1.08 (0.68, 1.71) | Adjusted for age, sex, education, marital status, partnership, smoking, risky alcohol consumption, physical activity, diagnosed diabetes mellitus, obesity, and hypertension. |

| Wiener et al(2014) | Stroke(17547) | self-reports | 0 teeth lost, 1.0 (reference); >1-<5, 1.29 (1.17, 1.42);>6-<32, 1.68 (1.50, 1.88); 32, 1.86(1.63, 2.11) | Adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, age, education, income levelm, health insurance, smoking status, physical activity outside of work, dental visits within the previous year, heavy drinking, diabetes and BMI. |

Tooth loss and cardiovascular disease risk

Twenty-eight independent reports from seventeen studies investigated the association between tooth loss and risk of coronary heart disease. Compared with the lowest tooth loss, tooth loss is significantly associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease (RR:1.52; 95% CI, 1.37–1.69; P < .001)(Fig 2). Subgroups analysis indicated that tooth loss is associated with a significantly increasement of coronary heart disease risk in Asia (RR:1.38; 95% CI, 1.21–1.56; P < .001)(Table 3) and Caucasian(RR:1.55; 95% CI, 1.35–1.75; P < .001)(Table 3). Furthermore, tooth loss was associated with a significantly cardiovascular disease risk in fatal cardiovascular disease (RR:1.31; 95% CI, 1.19–1.43; P < .001) (Table 3) and nonfatal cardiovascular disease (RR:1.56; 95% CI, 1.27–1.85; P < .001) (Table 3). Also, tooth loss was associated with a significantly risk of coronary heart disease in male (RR:1.92; 95% CI, 1.34–2.50; P < .001) (Table 3) and female (RR:1.48; 95% CI, 1.20–1.76; P < .001) (Table 3). Additionally, a significant dose-response relationship was observed between tooth loss and coronary heart disease risk. Increasing per 2 of tooth loss was associated with a 3% increment of coronary heart disease risk (RR:1.03; 95% CI, 1.02–1.04; P < .001) (Fig 3).

Fig 2. Forest plots for meta-analysis of tooth loss and risk of cardiovascular disease.

Table 3. Stratified analyses of relative risk of coronary heart disease and stroke.

| No of reports | Relative risk (95% CI) | P for heterogeneity | I2 | P for test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary heart disease | |||||

| Total cases | 28 | 1.52(1.37–1.69) | 0.000 | 88.3% | <0.001 |

| Fatal cases | 13 | 1.31(1.19–1.43) | 0.000 | 69.7% | <0.001 |

| Nonfatal cases | 15 | 1.56(1.27–1.85) | 0.000 | 89.1% | <0.001 |

| Subgroup analysis for total coronary heart disease | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 6 | 1.92(1.34–2.50) | 0.000 | 78.6% | <0.001 |

| Female | 6 | 1.48(1.20–1.76) | 0.137 | 40.2 | <0.001 |

| Study location | |||||

| Caucasia | 25 | 1.55(1.35–1.75) | 0.000 | 85.7% | <0.001 |

| Asia | 3 | 1.38(1.21–1.56) | 0.068 | 62.8% | <0.001 |

| No of participants | |||||

| ≥10 000 | 10 | 1.33(1.26–1.40) | 0.060 | 54.9% | <0.001 |

| <10 000 | 18 | 1.51(1.35–1.67) | 0.000 | 80.0% | <0.001 |

| No of cases | |||||

| ≥500 | 14 | 1.50(1.36–1.65) | 0.000 | 81.8% | <0.001 |

| <500 | 14 | 1.43(1.23–1.62) | 0.000 | 77.7% | <0.001 |

| Stroke | |||||

| Subgroup analyses for total stroke | |||||

| Total cases | 8 | 1.18(1.11–1.25) | 0.000 | 46.7% | <0.001 |

| Study location | |||||

| Caucasia | 5 | 1.25(1.18–1.32) | 0.001 | 67.8% | <0.001 |

| Asia | 3 | 1.12(1.01–1.23) | 0.528 | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| No of participants | |||||

| ≥10 000 | 4 | 1.43(1.27–1.60) | 0.000 | 88.9% | <0.001 |

| <10 000 | 4 | 1.08(1.02–1.15) | 0.643 | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| No of cases | |||||

| ≥500 | 6 | 1.30(1.17–1.44) | 0.000 | 74.9% | <0.001 |

| <500 | 2 | 1.09(1.03–1.15) | 0.590 | 0.0% | <0.001 |

Fig 3. Dose-response relationship between tooth loss and risk of cardiovascular disease.

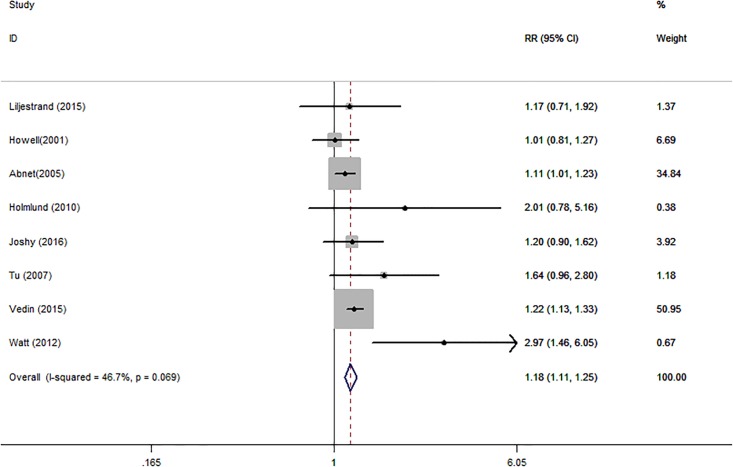

Tooth loss and stroke risk

Eight independent reports from eight studies investigated the association between tooth loss and risk of stroke. Compared with the lowest tooth loss, tooth loss is significantly associated with a higher risk of stroke (RR:1.18; 95% CI, 1.11–1.25; P < .001)(Fig 4). Subgroups analysis indicated that tooth loss is associated with a significantly incensement of stroke risk in Asia (RR:1.12; 95% CI, 1.01–1.23; P < .001) (Table 3) and Caucasian (RR:1.25; 95% CI, 1.18–1.32; P < .001) (Table 3). Additionally, a significant dose-response relationship was observed between tooth loss and stroke risk. Increasing per 2 of tooth loss was associated with a 3% increment of stroke risk (RR:1.03; 95% CI, 1.02–1.04; P < .001) (Fig 5).

Fig 4. Forest plots for meta-analysis of tooth loss and risk of stroke.

Fig 5. Dose-response relationship between tooth loss and risk of stroke.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analysis was performed to check the stability of the primary outcome. Subgroup meta-analyses in study design, study quality, number of participants and number of cases showed consistent findings (Table 3).

Publication bias

Each studies in this meta-analysis were performed to evaluate the publication bias by both Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test. P>0.05 was considered no publication bias. The results show no obvious evidence of publication bias was found in the relationship between tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke risk (S1 Table). A funnel plot for publication bias assessment is illustrated in S1 and S2 Figs.

Discussion

Recently, tooth loss has been found to be associated with decreased risks of lung cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer and pancreatic cancer[30]. However, as for tooth loss and coronary heart disease and stroke risk, there are several unsolved issues. First, the relationship between tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke risk is remains controversial. Some studies found that tooth loss was associated with a increase risk of coronary heart disease and stroke, whereas others failed to fnd relationship between tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke risk. Furthermore, the dose-response relationship between tooth loss and coronary heart disease and stroke risk has not been described.

In the current meta-analysis was based on seventeen cohort study, with a total of 879084 participants with 43750 incident cases. Thus, this meta analysis provides the most up-to-date epidemiological evidence supporting tooth loss is harmful for cardiovascular disease and stroke. A dose-response analysis revealed that increasing tooth loss (per 2 increment) was associated with a 3% increment of coronary heart disease risk, increasing tooth loss (per 2 increment) was associated with a 3% increment of stroke risk. Furthermore, tooth loss was associated with a significantly cardiovascular disease and stroke risk in Asia and Caucasian. Also, tooth loss was associated with a significantly risk of cardiovascular disease in male and female. Additionally, tooth loss was associated with a significantly cardiovascular disease and stroke risk in fatal cases and nonfatal cases. Subgroup meta-analyses by various factors also showed consistent findings.

Several plausible pathways may reasonable for the relationship between tooth loss and cancer. The influence of chronic inflammation on cancer development is one possible pathwa. Chronic systemic inflammation linked to periodontal disease. People with few or no teeth would this have an increased risk of systemic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and stroke[31]. Secondly, the main cause of teeth loss is dental caries, and carbohydrate intake is the dental caries cause. Carbohydrate intake was associated with increased risk cardiovascular disease and stroke, therefore teeth loss indirect effects risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke[32]. Third, the progress of tooth damage destroys normal periodontal tissue, allowing oral microbial accumulation deep into oral tissue, thereby promoting its growth, thus resulting in cardiovascular disease and stroke[33]. Fourth, Tooth loss is the ultimate stage of periodontal disease and may be associated with an increase in C-reactive protein (CRP), which itself is implicated in atherosclerosis and thus in the occurrence of stroke[34]. Thus, tooth loss and cancer seems to be closely related.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify and quantify the potential dose-response association between tooth loss and cardiovascular disease and stroke risk in a large cohort of both men and women. Although, we performed this meta-analysis very carefully, however, some limitations must be considered in the current meta-analysis. First, we only select literature that written by English, which may have resulted in a language or cultural bias, other language should be chosen in the further. Second, in the subgroup analysis in different ethnic population, there might be insufficient statistical power to check an association.

In conclusion, our dose–response meta-analysis suggests tooth loss was independently associated with deleterious coronary heart disease and stroke risk increment. In the future, large-scale and population based association studies must be performed to help identify the putative causal role that tooth loss plays in increasing the incidence of these diseases.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

This study received no specific external funding. Authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Ford ES, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in the U.S. from 1980 through 2002: concealed leveling of mortality rates. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50(22):2128–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.056 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):188–97. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182456d46 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celermajer DS, Chow CK, Marijon E, Anstey NM, Woo KS. Cardiovascular disease in the developing world: prevalences, patterns, and the potential of early disease detection. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;60(14):1207–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.074 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet (London, England). 2005;366(9499):1809–20. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67728-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerritsen AE, Allen PF, Witter DJ, Bronkhorst EM, Creugers NH. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2010;8:126 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adegboye AR, Twetman S, Christensen LB, Heitmann BL. Intake of dairy calcium and tooth loss among adult Danish men and women. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif). 2012;28(7–8):779–84. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2011.11.011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell TH, Ridker PM, Ajani UA, Hennekens CH, Christen WG. Periodontal disease and risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease in U.S. male physicians. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001;37(2):445–50. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hujoel PP, Drangsholt MT, Spiekerman C, DeRouen TA. Periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease. Jama. 2001;285(1):40–1. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hung HC, Joshipura KJ, Colditz G, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Speizer FE, et al. The association between tooth loss and coronary heart disease in men and women. Journal of public health dentistry. 2004;64(4):209–15. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joshipura KJ, Rimm EB, Douglass CW, Trichopoulos D, Ascherio A, Willett WC. Poor oral health and coronary heart disease. Journal of dental research. 1996;75(9):1631–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750090301 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joshy G, Arora M, Korda RJ, Chalmers J, Banks E. Is poor oral health a risk marker for incident cardiovascular disease hospitalisation and all-cause mortality? Findings from 172 630 participants from the prospective 45 and Up Study. BMJ open. 2016;6(8):e012386 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung YS, Shin MH, Kim IS, Kweon SS, Lee YH, Kim OJ, et al. Relationship between periodontal disease and subclinical atherosclerosis: the Dong-gu study. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2014;41(3):262–8. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12204 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liljestrand JM, Havulinna AS, Paju S, Mannisto S, Salomaa V, Pussinen PJ. Missing Teeth Predict Incident Cardiovascular Events, Diabetes, and Death. Journal of dental research. 2015;94(8):1055–62. doi: 10.1177/0022034515586352 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noguchi S, Toyokawa S, Miyoshi Y, Suyama Y, Inoue K, Kobayashi Y. Five-year follow-up study of the association between periodontal disease and myocardial infarction among Japanese male workers: MY Health Up Study. Journal of public health (Oxford, England). 2015;37(4):605–11. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdu076 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwahn C, Polzer I, Haring R, Dorr M, Wallaschofski H, Kocher T, et al. Missing, unreplaced teeth and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. International journal of cardiology. 2013;167(4):1430–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.061 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tu YK, Galobardes B, Smith GD, McCarron P, Jeffreys M, Gilthorpe MS. Associations between tooth loss and mortality patterns in the Glasgow Alumni Cohort. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2007;93(9):1098–103. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.097410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuominen R, Reunanen A, Paunio M, Paunio I, Aromaa A. Oral health indicators poorly predict coronary heart disease deaths. Journal of dental research. 2003;82(9):713–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200911 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vedin O, Hagstrom E, Budaj A, Denchev S, Harrington RA, Koenig W, et al. Tooth loss is independently associated with poor outcomes in stable coronary heart disease. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2016;23(8):839–46. doi: 10.1177/2047487315621978 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watt RG, Tsakos G, de Oliveira C, Hamer M. Tooth loss and cardiovascular disease mortality risk—results from the Scottish Health Survey. PloS one. 2012;7(2):e30797 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmlund A, Holm G, Lind L. Number of teeth as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in a cohort of 7,674 subjects followed for 12 years. Journal of periodontology. 2010;81(6):870–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090680 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abnet CC, Qiao YL, Dawsey SM, Dong ZW, Taylor PR, Mark SD. Tooth loss is associated with increased risk of total death and death from upper gastrointestinal cancer, heart disease, and stroke in a Chinese population-based cohort. International journal of epidemiology. 2005;34(2):467–74. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh375 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dietrich T, Jimenez M, Krall Kaye EA, Vokonas PS, Garcia RI. Age-dependent associations between chronic periodontitis/edentulism and risk of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2008;117(13):1668–74. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.711507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elter JR, Champagne CM, Offenbacher S, Beck JD. Relationship of periodontal disease and tooth loss to prevalence of coronary heart disease. Journal of periodontology. 2004;75(6):782–90. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.6.782 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Jama. 2000;283(15):2008–12. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Statistics in medicine. 1989;8(5):551–61. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. European journal of epidemiology. 2010;25(9):603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu C, Zeng XT, Liu TZ, Zhang C, Yang ZH, Li S, et al. Fruits and vegetables intake and risk of bladder cancer: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Medicine. 2015;94(17):e759 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orsini N, Li R, Wolk A, Khudyakov P, Spiegelman D. Meta-analysis for linear and nonlinear dose-response relations: examples, an evaluation of approximations, and software. American journal of epidemiology. 2012;175(1):66–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hiraki A, Matsuo K, Suzuki T, Kawase T, Tajima K. Teeth loss and risk of cancer at 14 common sites in Japanese. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2008;17(5):1222–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-07-2761 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Awan Z, Genest J. Inflammation modulation and cardiovascular disease prevention. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22(6):719–33. doi: 10.1177/2047487314529350 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He J, Li Y, Cao Y, Xue J, Zhou X. The oral microbiome diversity and its relation to human diseases. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2015;60(1):69–80. doi: 10.1007/s12223-014-0342-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dehghan M, Mente A, Zhang X, Swaminathan S, Li W, Mohan V, et al. Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2017;390(10107):2050–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32252-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.You Z, Cushman M, Jenny N, Howard G. Tooth loss, systemic inflammation, and prevalent stroke among participants in the reasons for geographic and racial difference in stroke (REGARDS) study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203(2):615–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.037 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.