Abstract

Viruses are molecular machines sustained through a life cycle that requires replication within host cells. Throughout the infectious cycle, viral and cellular components interact to advance the multistep process required to produce progeny virions. Despite progress made in understanding the virus-host protein interactome, much remains to be discovered about the cellular factors that function during infection, especially those operating at terminal steps in replication. In an RNA interference screen, we identified the eukaryotic chaperonin TRiC (also called CCT) as a cellular factor required for late events in the replication of mammalian reovirus. We discovered that TRiC functions in reovirus replication through a mechanism that involves the folding of the viral σ3 outer-capsid protein into a form capable of assembling onto virus particles. TRiC also complexes with homologous capsid proteins of closely related viruses. Our data define a critical function for TRiC in the viral assembly process and raise the possibility that this mechanism is conserved in related nonenveloped viruses. These results also provide insight into TRiC protein substrates and establish a rationale for the development of small-molecule inhibitors of TRiC as potential antiviral therapeutics.

INTRODUCTION

Viruses require cellular machinery to complete each step in a replication cycle. This machinery includes cell-surface receptors that mediate attachment, endosomal and cytoskeletal proteins involved in viral entry and uncoating, and the translational apparatus required for viral protein synthesis. Although progress has been made in understanding host proteins required for early events in viral infection, much less is known about the cellular machinery used by viruses to accomplish later replication steps.

Mammalian orthoreoviruses (reoviruses) infect most mammals and have been implicated in celiac disease pathogenesis in humans1. Reoviruses are nonenveloped and encapsidate a segmented, double-stranded RNA genome within a particle formed by an inner core and an outer capsid2. Reovirus enters the cell following attachment to membrane-bound receptors3,4 and clathrin-dependent endocytosis5, whereafter the particle is uncoated by cysteine proteases6, leading to delivery of the transcriptionally active core into the cytoplasm. In contrast to the well-characterized early infection steps, mechanisms governing genome assortment, assembly, transport, and egress remain unclear. We conducted a two-step RNA interference (RNAi)-based screen to identify host proteins required for late steps in reovirus replication. Our screen uncovered three primary gene networks operating late in infection, including multiple components of the TRiC (T-complex protein-1 ring complex) chaperonin.

TRiC is a ubiquitous, hetero-oligomeric complex formed by two eight-membered rings composed of paralogous subunits (CCT1-CCT8)7. These rings form a barrel-shaped structure with a central cavity that mediates ATP-dependent folding of newly translated proteins8–10. TRiC substrates often exhibit complex β-sheet topology, are aggregation-prone, and display slow folding kinetics11. Many TRiC substrates also are subunits that form higher-order structures, such as actin and tubulin12–14. A potential role for TRiC may exist in the replication of eukaryotic viruses. Certain viral proteins interact with TRiC15–17, and gene-silencing studies suggest that TRiC is required for the replication of some viruses18–20. However, a mechanism for TRiC in viral protein folding or particle assembly has not been described.

Here, we show that TRiC is essential for reovirus replication. We discovered that TRiC forms a complex with the reovirus σ3 outer-capsid protein and folds σ3 into its native conformation. We also provide evidence that TRiC renders σ3 into a conformation that can assemble onto mature particles, which is a critical step in viral assembly. These findings elucidate a dynamic pathway for the efficient folding of viral capsid components mediated by the TRiC chaperonin.

RESULTS

RNA interference screen for cellular mediators of late steps in reovirus replication identifies the TRiC chaperonin

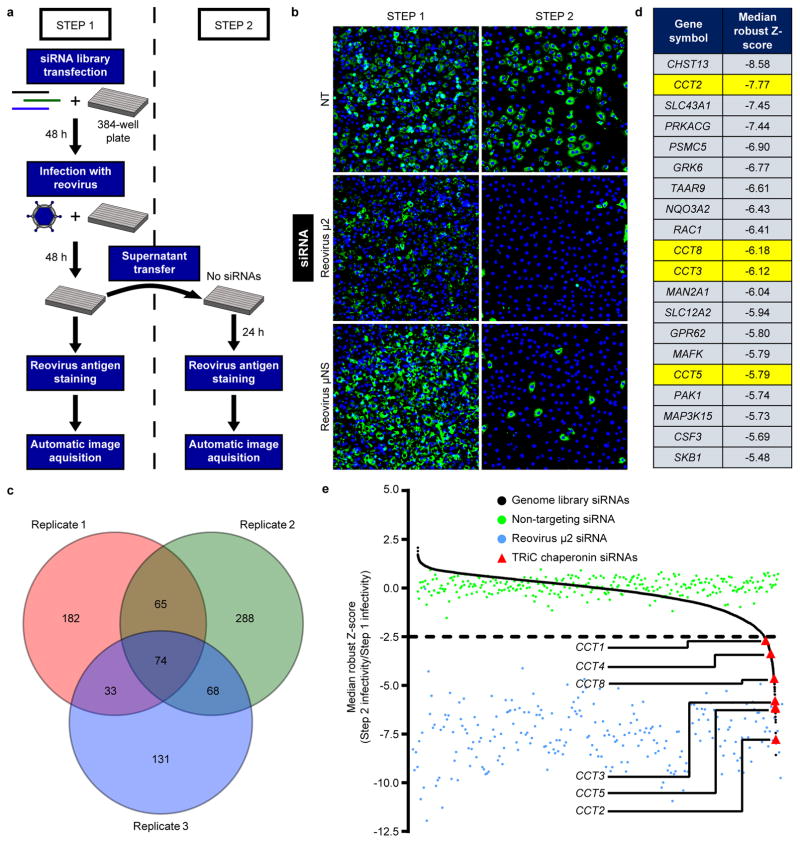

To identify host factors required for late steps in reovirus replication, we conducted a two-step RNAi-based screen to quantify reovirus replication after target gene knockdown (Fig. 1a). Human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs) were transfected with an siRNA library containing 7,518 siRNA pools, each targeting an individual human gene (step 1). After incubation for 48 hours (h), cells were infected with reovirus and incubated for an additional 48 h to allow replication and release of progeny. Supernatants were transferred to new plates containing fresh HBMECs (step 2), which were incubated for 24 h. Step 1 and step 2 cells were fixed, stained with a reovirus-specific antiserum, and imaged to quantify infectivity.

Figure 1. RNA-interference screen for cellular mediators of late steps in reovirus replication identifies the TRiC chaperonin.

a, High-throughput screening schematic. b, Representative immunofluorescence images from reovirus-infected step 1 and step 2 cells transfected with a non-targeting (NT) scrambled siRNA or reovirus-specific siRNAs (μ2 or μNS) and stained with DAPI (blue) and reovirus σNS-specific antiserum (green). c, Venn diagram of the number of genes with robust Z-score < −2.5 in each independent screen replicate. Overlapping regions indicate number of genes with a robust Z-score < −2.5 in multiple replicates. d, Top 20 candidate genes from the screen with Z-scores < −2.5 in all three replicates. TRiC chaperonin genes (CCT) are highlighted in yellow. e, Median robust Z-scores from three independent screen replicates for individual target genes (black, n = 7,418), NT siRNA (green, n = 288), reovirus μ2 siRNA (blue, n = 240), and CCT siRNAs (red).

As negative and positive controls for impaired virus release, HBMECs were transfected with a non-targeting (NT) scrambled siRNA or reovirus-specific siRNAs targeting the μ2 structural or μNS non-structural proteins. HBMEC transfection with an NT siRNA resulted in abundant infection of step 1 (81.7%) and step 2 (67.4%) cells, whereas μ2 or μNS targeting substantially reduced step 2 cell infectivity (13.6% and 13.1%, respectively) with little effect on infectivity of step 1 cells (70.5% and 85.3%, respectively) (Fig. 1b). We hypothesized that any host factor required for a late step in viral infection would mirror the infectivity results observed with μ2 and μNS knockdown.

To identify candidate host genes, siRNA pools that compromised cell viability were excluded, and robust Z-scores for the siRNA library targets were calculated using step 1 and step 2 infectivity values. Negative robust Z-scores reflect diminished virus release. Seventy-four genes were at or below a predetermined robust Z-score threshold in each of the three independent screen replicates (Fig. 1c). STRING protein-protein interaction network analysis revealed an enrichment of Ras/MAPK, ubiquitin/proteasome, and TRiC chaperonin gene networks (Supplementary Fig. 1). The top twenty candidates included chaperone components, kinases and phosphatases, molecule transporters, and various enzymes (Fig. 1d). Remarkably, six of the eight subunits of the TRiC chaperonin (CCT1, CCT2, CCT3, CCT4, CCT5, and CCT8) displayed median robust Z-scores less than −2.5, implicating this host chaperonin in viral replication (Fig. 1e).

The TRiC chaperonin is required for efficient reovirus replication, release, and protein expression

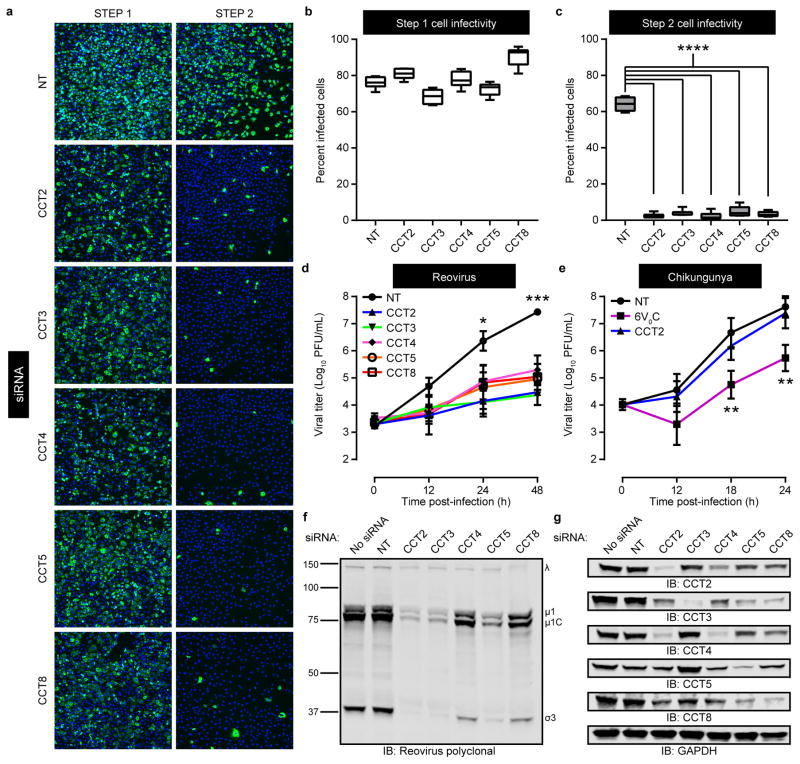

To validate the RNAi screen findings, we repeated the screening procedure using HBMECs transfected with pools of four TRiC-specific siRNAs unique from those used in the screen. Infectivity in step 1 cells transfected with TRiC-specific siRNAs was within 15% of infectivity in NT siRNA controls (Fig. 2a,b). However, TRiC disruption significantly reduced step 2 cell infectivity compared with NT controls (Fig. 2a,c). Thus, TRiC chaperonin knockdown decreases efficient release of infectious virus.

Figure 2. The TRiC chaperonin is required for efficient reovirus replication, release, and protein expression.

a, Representative immunofluorescence images of step 1 and step 2 T1L reovirus-infected HBMECs transfected with a non-targeting (NT) luciferase-specific siRNA or TRiC subunit-specific (CCT) siRNAs and stained with DAPI (blue) and reovirus σNS-specific antiserum (green). b,c, Quantification of step 1 (b) and step 2 (c) percent-infected cells from (a). Data are presented as box-and-whisker plots of six technical replicates and are representative of three independent experiments (****, P < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA). d,e, Viral titers from T1L reovirus-infected HBMECs (multiplicity of infection [MOI] of 1 plaque forming unit [PFU] per cell) (d) or chikungunya virus-infected U-2 OS cells (MOI of 0.01 PFU/cell) (e) transfected with NT or TRiC subunit-specific siRNAs. An siRNA targeting the 6V°C subunit of the vacuolar ATPase was used as a positive control to impair chikungunya virus replication22. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA). f,g, SDS-PAGE of HBMECs transfected with the indicated siRNAs, infected with T1L reovirus (MOI of 100 PFU/cell, 24 h post-infection), and immunoblotted for reovirus proteins (f) or TRiC subunits and GAPDH (g). Immunoblots are representative of three independent experiments conducted with similar results.

To determine the effect of TRiC disruption on reovirus replication, HBMECs were transfected with NT or TRiC-specific siRNAs and infected with reovirus. At 24 h post-infection, reovirus titers were ~100-fold lower in cells transfected with CCT2-, CCT3-, and CCT5-specific siRNAs compared to control cells (Fig. 2d). At 48 h post-infection, reovirus titers were ~100 to 1000-fold lower in cells transfected with each TRiC-specific siRNA compared with control cells. Similar results were observed in experiments using human adenocarcinoma cells and human embryonic kidney cells (Supplementary Fig. 2). Importantly, TRiC disruption did not alter cell viability (Supplementary Fig. 3). Disruption of TRiC also did not affect the replication of chikungunya virus, an unrelated enveloped RNA virus that replicates in the cytoplasm21. Combined, these data indicate that TRiC function is required for efficient reovirus replication and that the requirement is not universal for all viruses.

To assess whether TRiC disruption alters reovirus protein expression, HBMECs were transfected with NT or TRiC-specific siRNAs and infected with reovirus. At 24 h post-infection, cell lysates were prepared, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted for reovirus proteins (Fig. 2f) or TRiC subunits and GAPDH (Fig. 2g). RNAi knockdown of each TRiC subunit substantially reduced the levels of intracellular reovirus proteins, providing evidence that TRiC is required for the production or stabilization of viral polypeptides.

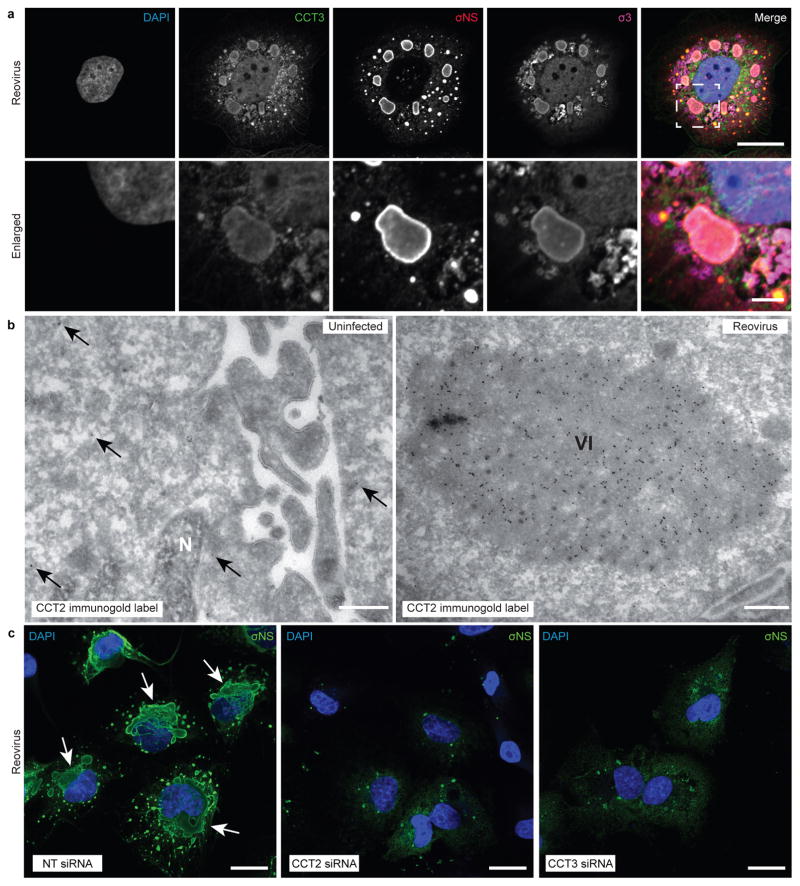

TRiC redistributes to viral inclusions and is required for inclusion morphogenesis

Reovirus forms inclusions in infected cells that serve as sites of progeny particle production23. To determine whether reovirus infection induces changes in the intracellular distribution of TRiC, we visualized TRiC in infected and uninfected cells by confocal and electron microscopy. The CCT1 and CCT3 TRiC subunits displayed a diffuse staining pattern in uninfected HBMECs (Supplemental Fig. 4). By contrast, their distribution was substantially altered in reovirus-infected cells, localizing primarily to viral inclusions (Fig. 3a). Electron microscopy of immunogold-labeled TRiC revealed sparse, diffuse staining in uninfected cells and concentrated, inclusion-associated staining in infected cells (Fig. 3b). These observations demonstrate that TRiC redistributes to sites of viral replication.

Figure 3. TRiC redistributes to viral inclusions and is required for inclusion morphogenesis.

a, Confocal immunofluorescence images of T3D reovirus-infected HBMECs (MOI of 100 PFU/cell, 24 h post-infection) stained with DAPI (blue), and antibodies specific for CCT3 (green), σNS (red), and σ3 (magenta). Viral inclusions are identifiable by σNS staining. Enlarged images correspond to the region indicated by the white dashed box in the merged image. Scale bars, 20 μm and 4 μm in full-sized and enlarged images, respectively. b, Tokuyasu cryosections of uninfected or T1L reovirus-infected (MOI of 1 PFU/cell, 20 h post-infection) HBMECs immunogold labeled for CCT2. Scale bars, 500 nm. Arrows indicate gold particles observed in uninfected cells. VI, viral inclusion; N, nucleus. c, Confocal immunofluorescence images of HBMECs transfected with NT or TRiC subunit-specific siRNAs, infected with T1L reovirus (MOI of 100 PFU/cell, 24 h post-infection), and stained with DAPI (blue) and a σNS-specific antiserum (green). Scale bars: 20 μm. Large, globular inclusions are marked by white arrows. Images are representative of three independent experiments conducted with similar results.

To determine the effect of TRiC disruption on viral inclusion morphogenesis, HBMECs were transfected with NT or TRiC-specific siRNAs, infected with reovirus, and imaged by confocal and electron microscopy. In contrast to cells transfected with an NT siRNA, cells transfected with siRNAs targeting TRiC subunits exhibited distorted inclusion morphology (Fig. 3c). Instead of forming large globular structures, inclusions appeared as puncta or diffuse throughout the cytoplasm. Electron microscopy of reovirus-infected cells treated with an NT siRNA revealed electron-dense viral inclusions with numerous mature particles (Supplementary Fig. 4). In cells transfected with TRiC-specific siRNAs, viral inclusions appeared abnormal, and virions were occasionally distorted. Thus, the TRiC chaperonin is required for formation of viral inclusions and production of virions with normal morphology.

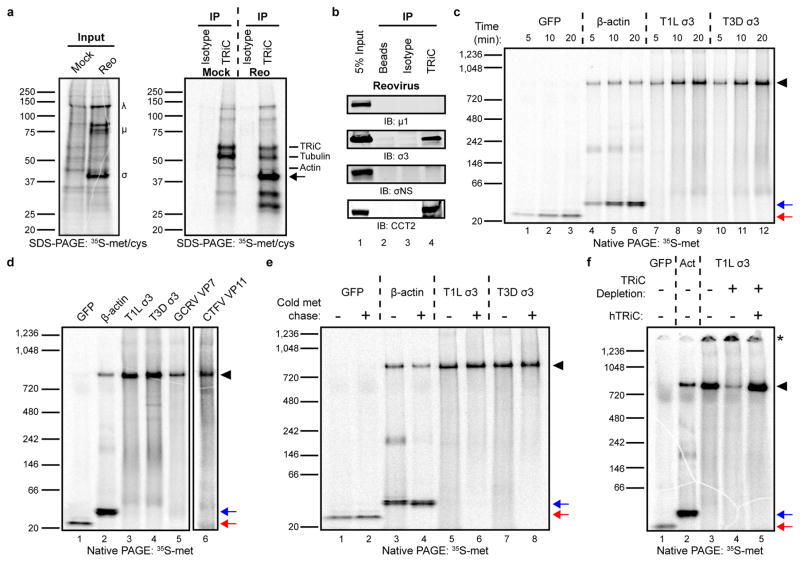

The TRiC chaperonin forms a complex with the reovirus σ3 outer-capsid protein

The TRiC chaperonin folds newly translated polypeptides through an ATP-dependent mechanism8–10. To determine whether TRiC folds one or more of the eleven viral proteins during infection, TRiC was immunoprecipitated from reovirus-infected HBMECs after metabolically labeling newly translated proteins with 35S-methionine/cysteine. SDS-PAGE of the input protein identified reovirus-specific large (λ), medium (μ), and small (σ) polypeptides in infected cells (Fig. 4a, left gel). SDS-PAGE of immunoprecipitated TRiC revealed known TRiC binding partners (actin and tubulin24) as well as an additional virus-specific band migrating at ~40 kilodaltons (kDa) (Fig. 4a, right gel). To confirm this interaction, TRiC was immunoprecipitated from reovirus-infected HBMECs, and co-immunoprecipitating proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for reovirus proteins. The same viral protein at ~40 kDa co-immunoprecipitated with the TRiC chaperonin (Supplementary Fig. 5). Using protein-specific monoclonal antibodies, the 40 kDa band was identified as σ3 (Fig. 4b, lane 4). Reovirus σ3 is an essential structural component that complexes with the viral μ1 protein to form μ13σ33 heterohexamers. These heterohexamers coalesce onto assembling virions to form the outer capsid25,26. The identification of an intracellular TRiC/σ3 complex led us to hypothesize that TRiC functions in reovirus replication by folding σ3 into its native state or contributing to its assembly into higher order structures.

Figure 4. The TRiC chaperonin forms a complex with the reovirus σ3 outer-capsid protein.

a, SDS-PAGE of mock or T1L reovirus-infected HBMECs (MOI of 100 PFU/cell, 20 h post-infection) pulsed-labeled for 5 min with 35S-methionine/cysteine. Left gel: 2% input protein. Large (λ), medium (μ), and small (σ) viral proteins are labeled. Right gel: immunoprecipitation with isotype control or TRiC-specific antibody. Virus-specific band at ~40 kDa denoted by arrow. b, SDS-PAGE of TRiC immunoprecipitated from T3D reovirus-infected HBMECs (MOI of 100 PFU/cell, 48 h post-infection) immunoblotted for μ1, σ3, σNS, and CCT2. c, Native PAGE of 35S-methionine (met)-labeled GFP, β-actin, and T1L and T3D reovirus σ3 translated for the intervals shown in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (RRLs). d, Native PAGE of 35S-met-labeled GFP, β-actin, T1L and T3D σ3, GCRV VP7, and CTFV VP11 translated for 1 h in RRLs. CTFV VP11 is shown separately due low methionine content, requiring an independent exposure. e, Native PAGE of 35S-met-labeled GFP, β-actin, and T1L and T3D σ3 translated in RRLs with (+) or without (−) a 4 h cold methionine chase. f, Native PAGE of 35S-met-labeled GFP, β-actin (Act), and T1L σ3 translated in mock-depleted (−) or TRiC-depleted (+) RRLs with or without addition of purified human TRiC (hTRiC; +, 0.25 μM). The asterisk denotes protein unable to enter the native gel. In all native gels, the black arrowhead indicates TRiC-bound substrate, and the red and blue arrows indicate free GFP and β-actin monomers, respectively. In a-f, three independent experiments were conducted with similar results.

To determine whether reovirus σ3 is a TRiC substrate, σ3 was translated in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (RRLs) in the presence of 35S-methionine (met), resolved by native PAGE, and visualized by phosphorimaging. RRLs are rich in chaperones, including TRiC, and have been used to identify putative TRiC substrates27,28. In addition to σ3, human β-actin (a TRiC substrate13,29) and green-fluorescent protein (GFP) (folds independently of TRiC28) were translated as controls. GFP migrated as a low molecular-weight monomer over the intervals of translation (Fig. 4c, lanes 1–3). β-actin migrated in two primary forms: a low molecular-weight monomer and a high molecular-weight ~800 kDa species corresponding to a TRiC-actin complex (Fig. 4c, lanes 4–6). In vitro translated σ3 from two prototype reovirus strains (T1L and T3D) migrated almost exclusively as a high molecular-weight species (Fig. 4c, lanes 7–12). A free σ3 monomer did not accumulate over time, suggesting that in vitro-translated σ3 remains bound to TRiC in a stable complex. To determine whether structurally-related viral outer-capsid proteins form a complex with TRiC, American grass carp aquareovirus (GCRV) VP7 and Colorado tick fever virus (CTFV, a coltivirus) VP11 were translated in RRLs. GCRV VP7 and CTFV VP11 migrated primarily as high molecular-weight complexes by native PAGE, as was observed with σ3 (Fig. 4d). Therefore, homologous capsid proteins of Reoviridae members form a complex with the TRiC chaperonin.

For certain substrates, TRiC functions as a holdase, retaining the polypeptide in a quasi-native state until an interaction with a binding partner or co-chaperone mediates a final folding or release event30,31. To assess the stability of the complex formed between σ3 and TRiC, σ3 was translated in the presence of 35S-met for 5 minutes, incubated with cold met for 4 h, and resolved by native (Fig. 4e) and SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 5). Newly translated β-actin migrated in both TRiC-bound and TRiC-free forms (Fig. 4e, lane 3). After a 4 h chase, the high molecular-weight TRiC-actin complex decreased in abundance with a corresponding increase in free, monomeric β-actin (Fig. 4e, lane 4). By contrast, in vitro-translated σ3 remained TRiC-bound throughout the duration of the cold met chase (Fig. 4e, lanes 5–8). These data indicate that the complex formed between TRiC and σ3 is stable long after translation has completed, suggesting that TRiC functions as a holdase for σ3.

To confirm that the high molecular-weight species in the in vitro translation reactions corresponds to TRiC-bound substrate, σ3 was translated in TRiC-immunodepleted RRLs and resolved by native PAGE (Fig. 4f). TRiC was reproducibly immunodepleted to levels 80–85% less than that of mock-depleted RRLs (Supplementary Fig. 5). The ~800 kDa form of σ3 was substantially reduced in TRiC-depleted RRLs (Fig. 4f, lane 4). In addition, σ3 translated in TRiC-depleted RRLs accumulated in a high-molecular weight form that did not enter the native gel, suggesting protein aggregation (Fig. 4f, lane 4, asterisk). Reconstitution of immunodepleted RRLs with purified human TRiC (hTRiC) restored the intensity of the ~800 kDa band (Fig. 4f, lane 5), providing evidence that the high molecular-weight species constitutes a stable TRiC-σ3 complex.

Since TRiC forms a complex with σ3, we hypothesized that the defects in viral protein production (Fig. 2f) and viral inclusion formation (Fig. 3c) with TRiC disruption are attributable to a failure in σ3 biogenesis. We tested whether siRNA disruption of σ3 mirrored the effect of TRiC disruption on viral inclusion formation. RNAi knockdown of σ3 in reovirus-infected cells resulted in decreased viral protein expression and distorted viral inclusions that failed to mature into large globular structures (Supplementary Fig. 6), mimicking results observed with TRiC knockdown. We conclude that the observed effects of TRiC disruption on viral protein synthesis and inclusion morphology are a result of defects in σ3 production.

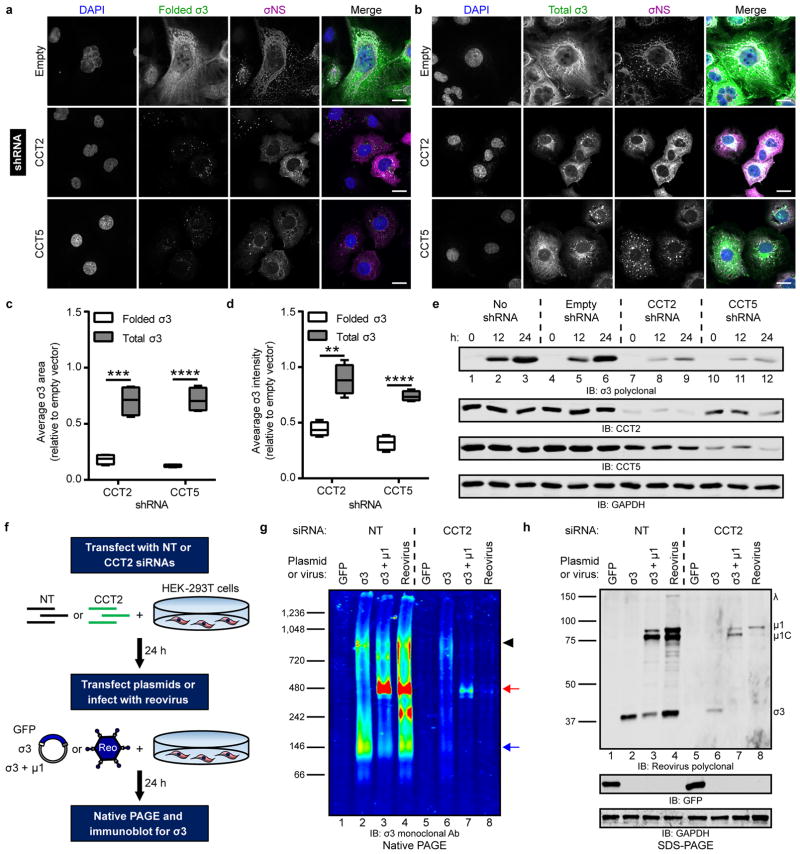

The intracellular biogenesis of native σ3 conformers requires the TRiC chaperonin

To determine whether TRiC is required to fold σ3 within infected cells, HBMECs expressing CCT2 or CCT5 shRNAs were infected with reovirus, and intracellular σ3 was visualized by confocal microscopy. Folded σ3 was detected using a conformation-sensitive monoclonal antibody specific for the native form of the protein32. TRiC disruption substantially reduced the forms of σ3 recognized by the conformation-specific antibody, whereas infected cells with intact TRiC produced abundant folded σ3 (Fig. 5a). To assess total levels of σ3, cells were stained with a σ3-specific polyclonal antiserum capable of recognizing folded and unfolded epitopes. Total σ3 immunofluorescence (folded and unfolded) was substantially greater compared with folded σ3 in TRiC-deficient cells (Fig. 5b). The average σ3 staining area (Fig. 5c) and intensity (Fig. 5d) were significantly greater for total σ3 relative to folded σ3. Despite the increased levels of total σ3 observed by confocal microscopy, the total amount of full-length, soluble σ3 detectable by immunoblotting was substantially reduced in TRiC-deficient cells (Fig. 5e, lanes 7–12). Therefore, TRiC disruption results in accumulation of σ3 conformers that are either partially translated, proteolytically cleaved, or aggregated and insoluble.

Figure 5. The intracellular biogenesis of native σ3 requires the TRiC chaperonin.

a,b, Immunofluorescence images of HBMECs stably transduced with TRiC subunit-specific shRNAs (or empty-vector), infected with T1L reovirus (MOI of 100 PFU/cell, 24 h post-infection), and stained with DAPI (blue) and antibodies specific for σNS (magenta) and folded (a, 10C1 monoclonal antibody) or total (b, VU219 polyclonal antiserum) σ3 (green). Scale bars, 20 μm. c,d, Quantification of folded or total σ3 staining area (c) or fluorescence intensity (d) per infected cell in CCT-shRNA transduced cells relative to empty vector control cells (> 200 cells quantified per experiment) from images acquired in (a) and (b). Data are presented as box-and-whisker plots of four independent experiments (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001, unpaired, two-tailed t-test). e, SDS-PAGE of shRNA-transduced HBMECs infected with T1L reovirus (MOI of 100 PFU/cell), harvested at the intervals shown, and immunoblotted for reovirus σ3, CCT2, CCT5, or GAPDH. f, Schematic of RNAi-knockdown and plasmid transfection or reovirus infection of HEK-293T cells. g, Native PAGE of HEK-293T cells transfected with a NT or TRiC subunit-specific siRNA and transfected with the indicated expression plasmids or infected with T3D reovirus (MOI of 100 PFU/cell, 24 h post-infection) and immunoblotted for σ3. Black arrowhead, TRiC-σ3 position; red arrow, μ13σ33 heterohexamer position; blue arrow, σ3 homo-oligomer position. h, SDS-PAGE of cell lysates from (g) immunoblotted for reovirus proteins, GFP, and GAPDH. Individual reovirus proteins are labeled. Immunoblots are representative of three independent experiments conducted with similar results.

To determine the effect of TRiC disruption on the production of native intracellular σ3, HEK-293T cells were transfected with an NT or TRiC-specific siRNA and transfected with expression plasmids or infected with reovirus (Fig. 5f). Cell lysates were resolved by native PAGE and immunoblotted for σ3 (Fig. 5g) or TRiC (Supplementary Fig. 7). Expression of all proteins was confirmed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5h). When expressed alone, σ3 migrated in two predominant forms: a low molecular-weight complex at ~140 kDa, corresponding to a σ3 homo-oligomer33,34, and a high molecular-weight complex at ~800 kDa, corresponding to the TRiC-bound form of σ3 (Fig. 5g, lane 2). When co-expressed with its outer-capsid binding partner, μ1, σ3 migrated primarily at a molecular weight of ~400 kDa (Fig. 5g, lane 3), corresponding to the assembled μ13σ33 heterohexamer35. In reovirus-infected cells, the forms of intracellular σ3 included the TRiC-bound species, μ13σ33 heterohexamer, and σ3 homo-oligomer, as well as an unknown band migrating at ~250 kDa (Fig. 5g, lane 4). RNAi disruption of TRiC resulted in a striking perturbation of the intracellular forms of σ3. When expressed alone in TRiC-disrupted cells, σ3 migrated as a single, low-intensity, high molecular-weight band corresponding to a complex with residual intracellular TRiC (Fig. 5g, lane 6). When co-expressed with μ1 in TRiC-disrupted cells, σ3 exclusively migrated as a faint band at ~400 kDa (Fig. 5g, lane 7). Finally, native intracellular σ3 was virtually undetectable in reovirus-infected, TRiC-disrupted cells (Fig. 5g, lane 8). Importantly, overall levels of de novo translation were not affected by TRiC disruption, as GFP expression was equivalent in cells treated with NT or TRiC-specific siRNAs (Fig. 5h, lane 1,5). These data indicate that TRiC is required for the intracellular production of the multiple native forms σ3.

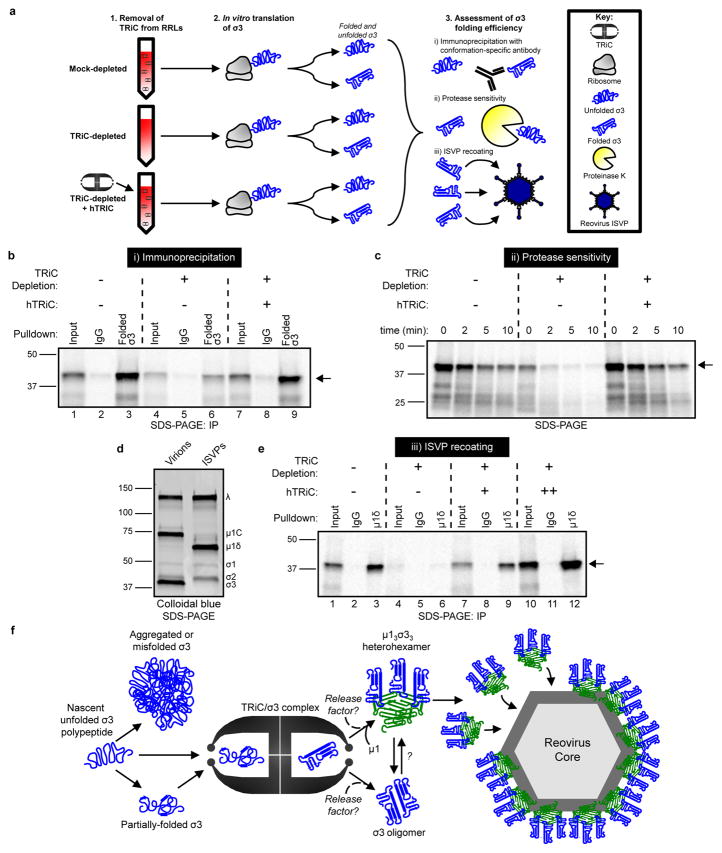

The TRiC chaperonin folds σ3 into a native, assembly-competent conformation

To determine whether TRiC directly folds σ3 into its native conformation, σ3 was translated in mock- or TRiC-depleted RRLs (Fig. 6a). Translated σ3 was immunoprecipitated using a conformation-specific antibody and resolved by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6a, i). Reovirus σ3 was efficiently immunoprecipitated from mock-depleted RRLs (Fig. 6b, lane 3). By contrast, there was a 67% reduction in the amount of σ3 immunoprecipitated from TRiC-depleted reactions (Fig. 6b, lane 6). Immunoprecipation of σ3 translated in TRiC-depleted RRLs reconstituted with hTRiC yielded levels comparable to mock-depleted RRLs (Fig. 6b, lane 9, quantified in Supplementary Fig. 8). To identify the σ3 species recognized by the conformation-specific antibody, we resolved the immunoprecipitation flow-through containing unbound protein by native PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 8). The σ3-specific antibody depleted the ~800 kDa form of σ3 from translation reactions, revealing that the antibody recognizes an exposed region of σ3 bound to TRiC. These results provide evidence that TRiC directly folds and retains σ3 in an exposed conformation capable of interacting with binding partners.

Figure 6. The TRiC chaperonin folds σ3 into a native, assembly-competent conformation.

a, Schematic of σ3 folding and assembly experiments. b, SDS-PAGE of 35S-met-labeled σ3 immunoprecipitated from RRLs using a conformation-specific antibody (10C1 monoclonal antibody) or isotype control. Where indicated, RRLs were TRiC-depleted and reconstituted with purified hTRiC (+, 0.25 μM) (10% input loaded into lanes 1,4,7). c, SDS-PAGE of 35S-met-labeled σ3 translated in RRLs mock-depleted, TRiC-depleted, or TRiC-depleted and reconstituted with purified hTRiC (+, 0.25 μM) and incubated with proteinase K (2.5 μg/mL final concentration) for the times shown. d, SDS-PAGE and colloidal blue stain of T1L reovirus virions and ISVPs. e, SDS-PAGE of ISVPs recoated with 35S-met-labeled σ3 translated in RRLs and immunoprecipitated using a μ1δ-specific antibody, which is specific to the μ1 species on ISVPs. Where indicated, RRLs were TRiC-depleted and reconstituted with purified hTRiC (+, 0.125 μM; ++, 0.50 μM) (20% input loaded into lanes 1,4,7,10). Arrows in SDS-PAGE gels indicate full-length σ3. In b–e, three independent experiments were conducted with similar results. f, Model of the TRiC-σ3 folding and assembly pathway.

To further test whether TRiC directly folds σ3, we quantified the protease sensitivity of σ3 translated in mock- or TRiC-depleted RRLs (Fig. 6a, ii). Unfolded proteins often exhibit increased protease sensitivity due to the exposure of additional cleavage sites36,37. Reovirus σ3 was translated in mock- or TRiC-depleted RRLs, digested with proteinase K for various intervals, and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Compared with mock-depleted RRLs, σ3 translated in TRiC-depleted RRLs displayed enhanced proteinase K sensitivity (Fig. 6c, Supplementary Fig. 8). Reconstitution of depleted RRLs with purified hTRiC decreased the sensitivity of translated σ3 to protease digestion, providing further evidence that TRiC folds σ3 into its native conformation.

To determine whether TRiC renders σ3 into a conformation capable of assembly, we tested whether reovirus infectious subvirion particles (ISVPs) could be recoated with σ3 translated in RRLs. (Fig. 6a, iii). ISVPs are naturally occurring reovirus disassembly intermediates formed during cell entry. These particles lack σ3 and contain a cleaved form of the σ3-binding partner, μ1 (μ1δ) (Fig. 6d). These particles can be recoated with purified σ3 to produce the mature outer capsid38. We translated σ3 in mock or TRiC-depleted RRLs (Fig. 6e), incubated reactions with ISVPs, and immunoprecipitated recoated particles with a μ1δ-specific antibody. We confirmed that this antibody recognizes μ1δ and not σ3 (Supplementary Fig. 8). TRiC depletion resulted in a 92% reduction in the efficiency of ISVP recoating (Fig. 6e, lane 6, quantified in Supplementary Fig. 8). Concordantly, reconstitution of RRLs with purified hTRiC restored recoating activity (Fig. 6e, lanes 9 and 12). Thus, TRiC folds σ3 into a conformation capable of recoating ISVPs, providing evidence that TRiC functions in viral particle assembly by folding the σ3 outer-capsid protein.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used an RNAi-based screen to identify cellular factors required for late steps in reovirus infection and discovered that the TRiC chaperonin mediates reovirus capsid protein folding. Found within all eukaryotic cells, TRiC interacts with 5–10% of cytoplasmic proteins and exhibits substrate specificity, although no consensus TRiC-binding determinants have been identified11. Our data support a model in which TRiC binds and folds reovirus σ3 into its native conformation, after which the folded protein is either retained within TRiC, released as a stable homo-oligomer, or incorporated into the μ13σ33 heterohexamer for assembly onto progeny virions (Fig. 6f). These observations enhance an understanding of the cell biology of reovirus infection and yield a new function for the TRiC chaperonin.

Presently no rules or patterns have been defined for viral substrates of the TRiC chaperonin. In certain cases, such as with reovirus σ3, retroviral Gag15,39, and hepatitis B virus core protein16, TRiC appears to fold capsid components, potentially directing their assembly into mature particles. For other viruses, TRiC interacts with less abundant non-structural proteins, such as Epstein-Barr virus EBNA-317 and hepatitis C virus NS5B18. In the case of capsid components, the requirement for TRiC-mediated folding might be due to the propensity of these proteins to rapidly misfold and form insoluble aggregates. As for viral non-structural proteins, the presence of multiple domains with independent folding requirements may dictate the need for TRiC. Why certain viruses require TRiC and others do not, and whether viral substrates of TRiC can be predicted, remain key unanswered questions.

Although we provide evidence that TRiC folds σ3, we do not understand the biochemical features that render σ3 an obligate TRiC substrate. A complex between TRiC and σ3 may form during translation to prevent nascent chain misfolding. Alternatively, σ3 may be refractory to spontaneous folding after release from ribosomes, requiring the exploration of various intermediates before achieving a native conformation. The structure of σ3 contains β-sheets that form via long-range intramolecular interactions33, and these secondary structures may not form spontaneously, requiring the iterative cycling of TRiC to complete the folding process. The σ3 protein also harbors a hydrophobic amino-terminal domain that forms the binding interface between homo-oligomers and molecules of μ1 in the μ13σ33 heterohexamer. This domain is likely insoluble and aggregation-prone in the aqueous cytoplasm, and TRiC, like other chaperonins40, may function to provide a thermodynamically favorable environment to allow the domain to fold. The combined effect of TRiC co-translational binding and iterative folding may be necessary for the efficient folding and assembly of σ3 onto new virus particles.

After folding, TRiC substrates are usually released from the interior chamber and exit into the cytosol. However, for certain substrates, such as the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein, release is more complex. After an initial folding event, TRiC functions as a holdase for VHL, retaining the protein in a quasi-native conformation competent for assembly into higher-order structures30. The complete folding and release of VHL occurs only after interaction with elongin-BC, the VHL binding-partner30. Our observation that σ3 translated in RRLs forms a stable complex with TRiC (Fig. 4d) suggests that TRiC functions as a σ3 holdase, stabilizing σ3 in a form primed for assembly. Through its holdase activity, TRiC could sequester aggregation-prone domains of σ3, such as the hydrophobic amino-terminus, and maintain the protein in a conformation competent for assembly into homo-oligomers or heterohexamers. Due to similarities in the replication cycles of Reoviridae viruses, we predict that this TRiC-mediated folding mechanism operates broadly to stabilize and assemble aggregation-prone viral capsid components.

Despite its observed holdase function, TRiC must liberate native σ3 for virus assembly. An interaction between TRiC-bound σ3 and nascent μ1 could trigger σ3 release. Alternatively, an unknown host co-chaperone could facilitate the productive release of native σ3 from TRiC. There is precedent for such a mechanism, as certain substrate-specific co-chaperones function following the action of TRiC to aid in the folding and assembly of oligomers. The α/β tubulin co-chaperones function following TRiC to assemble microtubules41, and phosducins participate in the assembly of the G-protein βγ dimer after TRiC-mediated β-subunit folding42. In the case of reovirus σ3, assembly into a complex with a host or viral protein is likely required for the release of the native protein following TRiC-mediated folding.

The different subunits in hetero-oligomeric TRiC have distinct binding specificities39 and, thus, substrate selection results from the combinatorial recognition of unique binding determinants in a substrate43,44. These binding determinants may associate with TRiC as helical structures, such as in a 54 amino acid stretch in the p6 domain of HIV Gag15,39, or in an extended state, as in a 6–9 amino acid sequence in Box 1 of VHL7,45. Our finding that outer-capsid proteins of mammalian orthoreovirus (σ3), aquareovirus (VP7), and coltivirus (VP11) bind to TRiC suggests that certain shared biochemical features facilitate chaperonin binding. These viral capsid proteins exhibit less than 20% amino acid identity but show similar hydrophobicity profiles in certain sequence regions46. These conserved hydrophobic regions may dictate TRiC binding and constitute a shared substrate motif, which supports a potential new determinant of TRiC binding.

Our results establish a function for the TRiC chaperonin in the folding of a nonenveloped virus capsid component. The broad conservation of TRiC in eukaryotes and the common principles of assembly of nonenveloped viruses raise the possibility that TRiC folds capsid components of other viruses. Findings reported here establish a foundation to better understand the rules governing TRiC substrate selection and set the stage for development of TRiC inhibitors as potentially broad-spectrum antiviral therapeutics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses

HBMECs were provided by Kwang Sik Kim47 (Johns Hopkins University) and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium as described. U-2 OS (ATCC HTB-96) cells were maintained in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented to contain 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). HEK-293T (ATCC CRL-3216) cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented to contain 10% FBS and 1% sodium pyruvate. Caco-2 cells (ATCC HTB-37) were maintained in DMEM supplemented to contain 10% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids, and 1% sodium pyruvate. Spinner-adapted murine L929 fibroblast cells were grown in either suspension or monolayer cultures as described48. Viral titers were determined by plaque assay using L929 cells as described49. Cell viability was quantified by PrestoBlue® assay (ThermoFisher, A13261) according the manufacturer’s instructions. HBMECs were tested for mycoplasma contamination using the Venor GeM mycoplasma detection kit (Sigma, MP0025). No authentication was performed on the cell lines used in this study.

Reovirus strains T1L and T3D were recovered using plasmid-based reverse genetics50 and purified as described51. Reovirus T1L M1 P208S, which harbors a point mutation in the M1 gene allowing it to form globular, T3D-like inclusions52, was used in the RNAi screen to facilitate visualization of reovirus-infected cells by high-throughput automated microscopy. The chikungunya virus 181/25 infectious clone plasmid was generated as described53.

siRNA and DNA transfections, plasmid cloning, and shRNA lentiviral transductions

Cells were reverse-transfected with siRNAs (Supplementary table 1) at a final concentration of 2.5 nM (HBMECs and U2-OS cells) or 5 nM (HEK-293T and Caco-2 cells) using Lipofectamine® RNAiMax (ThermoFisher, 13778075). Cells were used in viability, infection, imaging, and immunoblotting assays 48 h post-transfection. For transient DNA transfections of HEK-293T cells, 7.2 μg of pcDNA3.1+ expression vectors were combined with FuGene 6 (Promega, E2691) in Opti-MEM and incubated at RT for 15 min. DNA/FuGene mixtures were added dropwise onto 5 × 105 cells and incubated at 37°C for 24 h.

To engineer plasmids for transient transfection and in vitro translation studies, open reading frames were amplified by PCR using primers containing 5′ KpnI and 3′ NotI restriction sites (Supplementary table 2). PCR fragments were purified, digested, and ligated into the corresponding KpnI/NotI restrictions sites in the pcDNA3.1+ vector. The following templates were used for PCR amplification: Human β-actin (DNASU, HsCD00042977), American grass carp reovirus VP7 (GeneScript, Gene ID: 6218809), Colorado tick fever virus VP11 (GeneScript, Gene ID: 993319), peGFP-N1 (Addgene, 6085-1), pT7-T1L S4 (σ3) (Addgene, 33295), pT7-T3D S4 (σ3) (Addgene, 33285), pT7-T1L M2 (μ1) (Addgene, 33290).

To propagate shRNA-encoding lentiviruses, 1 × 107 HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with 0.6 μg pVSVG, 3 μg pCMV Lenti 8.92 Gag/Pol, and 6 μg of an empty shRNA control (Sigma, SHC201), CCT2-specific shRNA (Sigma, SHCLNG-NM_006431), or CCT5-specific shRNA (Sigma, SHCLNG-NM_012073) using the FuGene 6 transfection reagent. The culture medium was replaced 24 h post-transfection with complete RPMI medium, and cells were incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Medium containing packaged lentiviral particles was clarified by centrifugation at 4,000g at 4°C for 10 min and stored at −80°C. For lentiviral transduction, 3 mL of lentivirus-containing cell culture medium was combined with 3 μL of polybrene (Millipore, TR-1003-G), vortexed briefly, incubated at RT for 5 min, and added to HBMECs. After incubation overnight, the culture medium was supplemented to contain 1 μg/mL puromycin. Target knockdown was confirmed by immunoblotting.

In vitro transcription, translation, and 35S-metabolic labeling

Coupled in vitro transcription and translation reactions were conducted using the TNT coupled rabbit reticulocyte lysate system (Promega, L4610) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Using pcDNA3.1+ templates for in vitro transcription and translation, reactions were incubated at 30°C for variable intervals depending on the experimental conditions. Reactions were supplemented with [35S]-methionine (Perkin Elmer, NEG709A500UC) for radiolabeling and RNasin Plus RNase Inhibitor (N2611). Where indicated, reactions were chased with cold methionine added to a final concentration of 2 mM. Translation reactions were terminated by four-fold dilution in stop buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 100 mM potassium acetate, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM methionine) supplemented with a final concentration of 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 2 mM puromycin. Samples were used for immunoprecipitation, ISVP recoating, proteinase K (Sigma, P4850) digestion (final concentration of 2.5 μg/mL), or resolved by native and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

For metabolic labeling of de novo protein synthesis in cells, 4 × 106 HBMECs were infected with reovirus for 20 h. Cells were incubated in methionine/cysteine-free medium for 20 min, labeled with medium supplemented with 35S-methionine and cysteine (0.4 mCi/mL) (Perkin Elmer, NEG772007MC) for 5 min, and chased with medium supplemented with 50 mM cold methionine and cysteine for 1 min. Radiolabeled TRiC-bound proteins were isolated by immunoprecipitation and visualized by SDS-PAGE.

Native cell lysis, immunoprecipitations, and immunodepletions

Native HEK-293T cell lysates were prepared by suspending cells in ice-cold ATP depletion buffer (1 mM sodium azide, 2 mM 2-deoxyglucose, 5 mM EDTA, and 5 mM cycloheximide in phosphate-buffered saline without calcium and magnesium [PBS−/−]), followed by centrifugation at 300g at 4°C for 5 min. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer A (50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 100 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40) supplemented to contain 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, Sigma, P7626), protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, P8340), and benzoase (Sigma, E1014) and incubated on ice for 10 min. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 20,000g at 4°C for 10 min, and protein concentration was quantified using a DC protein assay (BioRad, 5000112). DTT was added to each sample to a final concentration of 1 mM, and equal amounts of protein sample were diluted in 4X Native PAGE Sample Buffer and Native PAGE G-250 Sample Additive (0.125% final concentration, ThermoFisher, BN2004).

To immunoprecipitate TRiC from reovirus-infected cells, HBMECs were harvested in ice-cold ATP-depletion buffer and collected by centrifugation at 300g at 4 °C for 5 min. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer B (50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail and lysed by dounce homogenization (70 strokes). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 20,000g at 4°C for 10 min. Clarified cell lysates were combined with 2 μg of a rabbit CCT2-specific monoclonal antibody (Abcam, ab92746) or an IgG isotype control antibody (Abcam, ab172730) and incubated at 4°C for 30 min with rotation. Cell lysates were combined with Protein G Dynabeads (ThermoFisher, 10004D) and incubated at 4°C for 30 min with rotation. Bead-bound antibody-antigen complexes were washed four times with ice-cold TRiC wash buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.05% NP-40), eluted with SDS sample buffer, and resolved by SDS-PAGE.

To immunoprecipitate proteins translated in vitro in RRLs, 5 μg of mouse 10C1 σ3 monoclonal antibody (for σ3 immunoprecipitations), mouse 8H6 μ1/μ1δ monoclonal antibody (for recoated ISVP immunoprecipitations), or IgG isotype control antibody (mouse 2F5 σNS monoclonal antibody)54 were incubated with reactions at 4°C for 1 h with rotation. Samples were added to Protein G Dynabeads and incubated at 4°C for 1 h with rotation. The flow-through containing unbound protein was resolved by native PAGE. Dynabeads were washed four times with Tris-buffered saline (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) containing 0.1% Tween-20, eluted with SDS sample buffer, and resolved by SDS-PAGE.

TRiC was immunodepleted from RRLs by incubating 75 μL of RRLs with 8 μg of a rabbit CCT2-specific polyclonal antiserum28 or an equivalent volume of resin buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 25 mM KCl, 0.5 mM magnesium acetate) and incubated at 4°C for 2 h with rotation. Protein A-agarose fast flow resin (Sigma, P3476) was pre-washed four times with 1 mL of resin wash buffer. RRLs were incubated with protein A beads at 4°C for 2 h, and bead-bound antibody/TRiC complexes were collected by centrifugation at 2,000g at 4 °C for 5 min. This process was repeated twice with the supernatant to further deplete TRiC. Where indicated, RRLs were reconstituted with recombinant human TRiC (provided by the Frydman laboratory, Stanford University).

Native and SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting, phosphorimaging

Native PAGE

Samples for native PAGE were diluted in 4X Native PAGE Sample Buffer (ThermoFisher, BN2003) and loaded into wells of 4–16% Native PAGE Bis-Tris acrylamide gels (ThermoFisher). Samples were electrophoresed using the blue native PAGE Novex Bis-Tris gel system (ThermoFisher) at 150V at 4°C for 60 min, followed by 250V at 4°C for 40 min. Light blue anode buffer was supplemented with 0.1% L-cysteine and 1 mM ATP. Following electrophoresis, gels were incubated in 40% methanol, 10% acetic acid at RT for 1 h, washed three times with ddH2O, and dried on filter paper at 80°C for 2 h using a BioRad model 583 gel dyer. Dried gels were exposed on a phosphorimaging screen for 12–36 h and imaged using a Perkin Elmer Cyclone Phosphor System Scanner (B431200). Protein bands labeled with 35S-met were analyzed using ImageJ software55. To immunoblot native cell lysates, samples were resolved by blue native PAGE with the following modification: DTT was added to the light blue cathode buffer to a final concentration of 1 mM. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (BioRad, 162-0177) at 25 V at 4°C for 2 h. Following transfer, the membrane was soaked in 8% acetic acid for 15 min, rinsed with ddH2O, and dried. The membrane was incubated with 100% methanol for 1 min, rinsed with ddH2O, blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) diluted in PBS−/−, and incubated with antibodies for immunoblotting. All native gels were electrophoresed with the NativeMark Protein Standard (ThermoFisher, LC0725) for molecular weight estimation.

SDS-PAGE

Samples for denaturing PAGE were diluted in 5X SDS-PAGE sample buffer and incubated at 95°C for 10 min. Samples were loaded into wells of 10% acrylamide gels (BioRad, 4561036) and electrophoresed at 100V for 90 min. Follow electrophoresis, gels were either stained with colloidal blue (ThermoFisher, LC6025) or transferred to nitrocellulose for immunoblotting. Immunoblot analysis was performed as described56 and scanned using an Odyssey CLx imaging system (Li-Cor).

The following antibodies were used for immunoblotting: guinea pig σNS polyclonal antiserum57, rabbit reovirus-specific polyclonal antiserum58, mouse 4F2 σ3 monoclonal antibody32, rabbit VU219 σ3 polyclonal antiserum (this study), mouse 8H6 μ1/μ1δ monoclonal antibody32, rat CCT1 monoclonal antibody (Enzo Life Sciences, ADI-CTA-123), rabbit CCT2 monoclonal antibody (Abcam, ab92746), rabbit CCT3 polyclonal antiserum (ABclonal, A6547), mouse CCT4 monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, sc-137092), rabbit CCT5 monoclonal antibody (Abcam, ab129016), mouse CCT8 polyclonal antibody (Novus Biologicals, H00010694-B02P), mouse GAPDH monoclonal antibody (Sigma, G8795), and rabbit GFP polyclonal antiserum (Santa-Cruz, sc-8334).

Immunofluorescence microscopy, image analysis, and quantification

Confocal microscopy was performed as described48 with the following modifications: cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Electron Microscopy Sciences, 15712-s) diluted in PBS−/− at RT for 20 min and counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Invitrogen, D3571) to label nuclei. Confocal images were captured using a Zeiss LSM 710 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with a 63X oil objective. Images were processed using Zen 2012 and ImageJ software with the Fiji plugin55. Immunofluorescence images to quantify folded and unfolded reovirus σ3 were captured using a Lionheart FX automated microscope (BioTek) equipped with a 20X air objective. Images were processed and signals quantified using Gen5+ software (BioTek). The following antibodies were used: guinea pig σNS polyclonal antiserum57, mouse 10C1 σ3 monoclonal antibody (conformation-specific antibody, used to label native σ3)32, rabbit VU219 σ3 polyclonal antiserum (used to label total σ3), rabbit anti-CCT1 polyclonal antiserum (NeoScientific, A1950), rabbit CCT3 polyclonal antiserum (ABclonal, A6547).

ISVP purification and recoating

To generate ISVPs, 2 × 1012 purified T1L reovirus particles were incubated with chymotrypsin (Sigma, C3142) diluted to 200 μg/mL at 37°C for 60 min. Digestion was terminated by the addition of PMSF to a final concentration of 2 mM. ISVPs were purified by cesium chloride gradient (1.25 g/mL to 1.45 g/mL) centrifugation with a Beckman Coulter Optima L-90K ultracentrifuge and SW-41 rotor at 25,000 rpm at 5°C overnight. Purified ISVPs were dialyzed in four 1-L volumes of virion storage buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2) and stored at 4°C. Virion-to-ISVP conversion was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and colloidal blue staining to assess the loss of σ3 and cleavage of μ1C to μ1δ. For recoating experiments, ISVPs (5 × 1010) or an equal volume of virion storage buffer were added to in vitro translated σ3 and incubated at 37°C for 2 h.

Electron microscopy

Cells were incubated with a mixture of 4% PFA and 1% glutaraldehyde in 0.4 M HEPES buffer, pH 7.4 at RT for 1 h. Cells were incubated with 1% osmium tetroxide and 0.8% potassium ferricyanide in water at 4°C for 1 h and dehydrated in 5-min steps with increasing concentrations of acetone (50%, 70%, 90%, and twice in 100%) at 4°C. Samples were incubated at RT overnight with a 1:1 mixture of acetone-resin, infiltrated for 8 h in pure epoxy resin EML-812 (TAAB Laboratories)23, and polymerized at 60°C for 48 h. Ultrathin (~ 60 nm) oriented serial sections were prepared using a UC6 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems), collected on uncoated 300-mesh copper grids (TAAB Laboratories), stained with saturated uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and imaged by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Images were acquired using a JEOL JEM 1011 electron microscope operating at 100 kv. Reovirus inclusion and particle morphology were assessed by imaging more than 100 HBMECs reverse-transfected with non-targeting (luciferase siRNA) or TRiC subunit-specific siRNAs by TEM.

For immunogold labeling on thawed cryosections (Tokuyasu method59,60), cells were incubated with 4% PFA in PHEM buffer, pH 7.2 (60 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis (2-ethanesulfonic acid), 25 mM HEPES, 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2) at RT for 2 h, followed by 50 mM NH4Cl to quench free aldehydes groups. Cells were collected by centrifugation, embedded in 12% gelatin (TAAB Laboratories) in PBS, and incubated on ice for 15 min. Pellets were divided into 1 mm3 cubes and incubated at 4°C overnight with 2.1 M sucrose in PBS. Blocks were mounted on metal pins and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Ultrathin cryosections (50–100 nm) were prepared using a diamond knife and a UC6 cryoultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems) operating at −120°C. Sections were collected using a mixture of 2% methylcellulose in H2O and 2.1 M sucrose in PBS (1:1) and transferred to 200-mesh grids with a carbon-coated Formvar film. Grids were incubated with PBS at 37°C for 25 min in a humid chamber. Free aldehydes were quenched with 50 mM NH4Cl (five times at 2 min each) before incubation with 1% BSA for 5 min. Cryosections were incubated with a rabbit CCT2-specific monoclonal antibody (Abcam, ab92746) diluted 1:20 in 1% BSA for 1 h. After washes with 0.1% BSA (five times at 2 min each) and 1% BSA (5 min), grids were incubated for 30 min with a secondary antibody conjugated with 10 nm colloidal gold particles (BB International) diluted 1:50 in 1% BSA. Cryosections were washed with 0.1% BSA (twice at 2 min each) and PBS (three times at 2 min each) before incubation with 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 5 min. After washing with water (nine times at 2 min each), grids were incubated with uranyl acetate and methylcellulose (9:1) on ice for 5 min. Grids were collected, dried, and imaged using a JEOL JEM 1011 electron microscope operating at 100 kv. Immunogold-labeled Tokuyasu cryosections were prepared from more than 50 mock-infected cells and more than 50 reovirus-infected cells.

High-throughput RNA-interference screen

Day 1: Reverse transfection of siRNA library (step 1)

The Dharmacon® human ON-TARGETplus druggable genome siRNA library (7,518 genes total with pools of four unique siRNAs targeting each gene) was aliquoted in triplicate into black, clear-bottom, 384-well plates (Greiner, 781091) for a final diluted siRNA concentration of 25 nM. Control siRNAs targeting JAM-A (receptor for reovirus), reovirus μ2, reovirus μNS, and a non-targeting control were seeded into empty wells. As a control for transfection efficiency, wells also were seeded with the AllStars Cell Death control siRNA (Qiagen). Lipofectamine® RNAiMax transfection reagent was diluted in Opti-MEM reduced-serum medium, and aliquoted into each well (0.07 μL RNAiMax per well). Following a 15-min incubation at room temperature (RT), the siRNA/lipid solution was combined with 5 × 102 HBMECs per well in complete RPMI medium. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 48 h to allow efficient target knockdown.

Day 3: Reovirus infection

Previously transfected HBMECs were adsorbed with reovirus T1L M1 P208S at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1000 plaque forming units (PFU) per cell at 37°C for 3 h. Cells were washed twice with PBS−/−, supplemented with complete RPMI medium, and incubated at 37°C for 48 h.

Day 5: Supernatant transfer and fixation of step 1 cells

The cell culture medium (30 μL) covering step 1 infected cells was transferred to V-bottom 384-well plates using an Agilent Bravo automated liquid handling platform. The remaining medium covering step 1 cells was removed, and cells were incubated with ice-cold 100% methanol and stored at −20°C. Supernatants in V-bottom plates were centrifuged at 1000 rpm at RT for 10 min to collect cellular debris. The supernatant was transferred to new (step 2) 384-well plates. HBMECs (2 × 103 cells per well) were seeded on top of the transferred supernatants and cultured at 37°C for 24 h.

Day 6: Fixation of step 2 cells

The culture medium covering step 2 cells was aspirated, and cells were incubated with ice-cold 100% methanol and stored at −20°C.

Day 7: Immunofluorescence staining

Step 1 and step 2 cells were brought to RT, the methanol fixative was aspirated, and cells were washed twice with PBS−/−. PBS−/− containing 5% BSA was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The BSA blocking solution was aspirated, and cells were incubated with a reovirus σNS-specific guinea pig polyclonal antiserum diluted 1:2000 in PBS−/− containing 0.5% Triton-X 100 (PBS-T) at 37°C for 1 h. Cells were washed twice with PBS−/− and incubated with DAPI and a guinea pig-specific Alexa 488 secondary antibody (diluted 1:1000) in PBS-T at 37°C for 1 h. Cells were wash twice with PBS−/− and covered with H2O for imaging.

Day 8: High-content imaging

Fluorescent images were captured using an ImageXpress Micro XL (Molecular Devices) automated microscope equipped with a 20X air objective. Four independent fields of view were acquired for each well.

Day 9: Quantitative image analysis

Reovirus-infected HBMECs in step 1 and step 2 plates were enumerated using MetaXpress image analysis software (Molecular Devices). Fluorescence intensity thresholds were defined to identify objects containing DAPI (total cell count) and objects containing DAPI and Alexa 488 (infected cell count). The percentage of infected cells was calculated by dividing the infected cell count by the total cell count and multiplying by 100.

Data analysis

The efficiency of reovirus release from step 1 cells and subsequent infection of step 2 cells was determined by dividing the percentage of infected cells in step 2 plates by the percentage of infected cells in step 1 plates. We termed this calculation the egress ratio. The egress ratio for each siRNA pool was transformed to a log2 scale. Candidate genes were identified by calculating robust Z-scores using the log-transformed egress ratios. The log-transformed egress ratio values of the aggregate samples in each 384-well plate were used to calculate median and median absolute deviation values. The robust Z-scores for individual genes were then calculated using the formula below:

As a viability filter, all siRNAs that decreased the number of step 1 cells beyond 2.5 standard deviations from the screen mean were removed from the analysis (102/7,518 = 1.35% of genes). A median robust Z-score cutoff of −2.5 was applied across the three replicates of the remaining 7,416 genes to identify candidate mediators of late steps in reovirus replication. All screening experiments were conducted in the Vanderbilt High Throughput Screening Core.

STRING protein-protein interaction prediction

STRING functional protein association network analysis61 was conducted using the 242 candidate genes with median robust Z-scores less than or equal to −2.5. Of the candidate genes, 241 were recognized in the analysis and assembled into an interactome map. The Kmeans clustering algorithm was used to group the genes into four clusters.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed with a minimum of three independent replicates. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests were used with an α = 0.05. Where indicated, ordinary one-way ANOVA analyses were performed with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, α = 0.05. For all box-and-whisker plots, whiskers denote minimum and maximal values, boxes denote 25th and 75th percentiles, and the center denotes the median value. Exact P-values and confidence intervals are tabulated in Supplementary Table 3. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 7.00 data analysis software.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Purified recombinant human TRiC is a limited resource that was provided by the Frydman Lab (Stanford University). Please contact Judith Frydman directly (jfrydman@stanford.edu) for inquiries directly related to purified human TRiC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service awards AI032539, AI122563, GM007347, UL1TR000445, and the Vanderbilt Lamb Center for Pediatric Research. The RNAi screen was performed in the Vanderbilt high-throughput screening facility, which is an institutionally supported core. Confocal images were captured in the cell imaging core at the Rangos Research Center at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. The authors thank Pavithra Aravamudhan, Judy Brown, Bernardo Mainou, Laurie Silva, Danica Sutherland, and Gwen Taylor of the Dermody lab for essential discussions and critically editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRBUTIONS

J.J.K. conceived and designed experiments, performed experiments, analyzed data, contributed materials/analysis tools, and wrote the paper. T.S.D. conceived and designed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. I.F.D., A.W.A., and P.F.Z. conceived and designed experiments, performed experiments, and analyzed data. J.A.B. conceived and designed experiments and performed experiments. D.R.G, J.F., and C.R. conceived and designed experiments, analyzed data, and contributed materials/analysis tools. J.C.F. analyzed data. All authors reviewed, critiqued, and provided comments on the manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Bouziat R, et al. Reovirus infection triggers inflammatory responses to dietary antigens and development of celiac disease. Science. 2017;356:44–50. doi: 10.1126/science.aah5298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dermody TS, Parker JS, Sherry B. Orthoreoviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2013. pp. 1304–1346. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton ES, et al. Junction adhesion molecule is a receptor for reovirus. Cell. 2001;104:441–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konopka-Anstadt JL, et al. The Nogo receptor NgR1 mediates infection by mammalian reovirus. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:681–91. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maginnis MS, et al. NPXY motifs in the β1 integrin cytoplasmic tail are required for functional reovirus entry. Journal of Virology. 2008;82:3181–3191. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01612-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebert DH, Deussing J, Peters C, Dermody TS. Cathepsin L and cathepsin B mediate reovirus disassembly in murine fibroblast cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24609–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leitner A, et al. The molecular architecture of the eukaryotic chaperonin TRiC/CCT. Structure. 2012;20:814–25. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bigotti MG, Clarke AR. Chaperonins: The hunt for the Group II mechanism. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;474:331–9. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature. 2011;475:324–32. doi: 10.1038/nature10317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spiess C, Meyer AS, Reissmann S, Frydman J. Mechanism of the eukaryotic chaperonin: protein folding in the chamber of secrets. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yam AY, et al. Defining the TRiC/CCT interactome links chaperonin function to stabilization of newly made proteins with complex topologies. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:1255–62. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frydman J, et al. Function in protein folding of TRiC, a cytosolic ring complex containing TCP-1 and structurally related subunits. EMBO J. 1992;11:4767–78. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao Y, Thomas JO, Chow RL, Lee GH, Cowan NJ. A cytoplasmic chaperonin that catalyzes beta-actin folding. Cell. 1992;69:1043–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90622-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao Y, Vainberg IE, Chow RL, Cowan NJ. Two cofactors and cytoplasmic chaperonin are required for the folding of alpha- and beta-tubulin. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2478–85. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong S, et al. Type D retrovirus Gag polyprotein interacts with the cytosolic chaperonin TRiC. J Virol. 2001;75:2526–34. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2526-2534.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lingappa JR, et al. A eukaryotic cytosolic chaperonin is associated with a high molecular weight intermediate in the assembly of hepatitis B virus capsid, a multimeric particle. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:99–111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashuba E, Pokrovskaja K, Klein G, Szekely L. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded nuclear protein EBNA-3 interacts with the epsilon-subunit of the T-complex protein 1 chaperonin complex. J Hum Virol. 1999;2:33–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue Y, et al. Chaperonin TRiC/CCT participates in replication of hepatitis C virus genome via interaction with the viral NS5B protein. Virology. 2011;410:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, et al. Cellular chaperonin CCTgamma contributes to rabies virus replication during infection. J Virol. 2013;87:7608–21. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03186-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fislova T, Thomas B, Graef KM, Fodor E. Association of the influenza virus RNA polymerase subunit PB2 with the host chaperonin CCT. J Virol. 2010;84:8691–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00813-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solignat M, Gay B, Higgs S, Briant L, Devaux C. Replication cycle of chikungunya: a re-emerging arbovirus. Virology. 2009;393:183–97. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sourisseau M, et al. Characterization of reemerging chikungunya virus. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e89. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez de Castro I, et al. Reovirus forms neo-organelles for progeny particle assembly within reorganized cell membranes. MBio. 2014;5 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00931-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thulasiraman V, Yang CF, Frydman J. In vivo newly translated polypeptides are sequestered in a protected folding environment. EMBO J. 1999;18:85–95. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shing M, Coombs KM. Assembly of the reovirus outer capsid requires mu 1/sigma 3 interactions which are prevented by misfolded sigma 3 protein in temperature-sensitive mutant tsG453. Virus Res. 1996;46:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(96)01372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandran K, et al. In vitro recoating of reovirus cores with baculovirus-expressed outer-capsid proteins μ1 and σ3. Journal of Virology. 1999;73:3941–3950. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3941-3950.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasembeli M, et al. Modulation of STAT3 folding and function by TRiC/CCT chaperonin. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freund A, et al. Proteostatic control of telomerase function through TRiC-mediated folding of TCAB1. Cell. 2014;159:1389–403. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian G, Vainberg IE, Tap WD, Lewis SA, Cowan NJ. Specificity in chaperonin-mediated protein folding. Nature. 1995;375:250–3. doi: 10.1038/375250a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldman DE, Thulasiraman V, Ferreyra RG, Frydman J. Formation of the VHL-elongin BC tumor suppressor complex is mediated by the chaperonin TRiC. Mol Cell. 1999;4:1051–61. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyata Y, Shibata T, Aoshima M, Tsubata T, Nishida E. The molecular chaperone TRiC/CCT binds to the Trp-Asp 40 (WD40) repeat protein WDR68 and promotes its folding, protein kinase DYRK1A binding, and nuclear accumulation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:33320–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.586115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Virgin HW, IV, Mann MA, Fields BN, Tyler KL. Monoclonal antibodies to reovirus reveal structure/function relationships between capsid proteins and genetics of susceptibility to antibody action. Journal of Virology. 1991;65:6772–6781. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6772-6781.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olland AM, Jané-Valbuena J, Schiff LA, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. Structure of the reovirus outer capsid and dsRNA-binding protein σ3 at 1.8 Å resolution. EMBO Journal. 2001;20:979–989. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.5.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller JE, Samuel CE. Proteolytic cleavage of the reovirus σ3 protein results in enhanced double-stranded RNA-binding activity: identification of a repeated basic amino acid motif within the C-terminal binding region. Journal of Virology. 1992;66:5347–5356. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5347-5356.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liemann S, Chandran K, Baker TS, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. Structure of the reovirus membrane-penetration protein, μ1, in a complex with its protector protein, σ3. Cell. 2002;108:283–295. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00612-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin J, et al. Chaperonin-mediated protein folding at the surface of groEL through a ‘molten globule’-like intermediate. Nature. 1991;352:36–42. doi: 10.1038/352036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frydman J, Nimmesgern E, Ohtsuka K, Hartl FU. Folding of nascent polypeptide chains in a high molecular mass assembly with molecular chaperones. Nature. 1994;370:111–7. doi: 10.1038/370111a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jané-Valbuena J, et al. Reovirus virion-like particles obtained by recoating infectious subvirion particles with baculovirus-expressed σ3 protein: an approach for analyzing σ3 functions during virus entry. Journal of Virology. 1999;73:2963–2973. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2963-2973.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joachimiak LA, Walzthoeni T, Liu CW, Aebersold R, Frydman J. The structural basis of substrate recognition by the eukaryotic chaperonin TRiC/CCT. Cell. 2014;159:1042–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Georgescauld F, et al. GroEL/ES chaperonin modulates the mechanism and accelerates the rate of TIM-barrel domain folding. Cell. 2014;157:922–934. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tian G, Cowan NJ. Tubulin-specific chaperones: components of a molecular machine that assembles the alpha/beta heterodimer. Methods Cell Biol. 2013;115:155–71. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407757-7.00011-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plimpton RL, et al. Structures of the Gbeta-CCT and PhLP1-Gbeta-CCT complexes reveal a mechanism for G-protein beta-subunit folding and Gbetagamma dimer assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:2413–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419595112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spiess C, Miller EJ, McClellan AJ, Frydman J. Identification of the TRiC/CCT substrate binding sites uncovers the function of subunit diversity in eukaryotic chaperonins. Mol Cell. 2006;24:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leroux MR, Hartl FU. Protein folding: versatility of the cytosolic chaperonin TRiC/CCT. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R260–4. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00432-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feldman DE, Spiess C, Howard DE, Frydman J. Tumorigenic mutations in VHL disrupt folding in vivo by interfering with chaperonin binding. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1213–24. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Attoui H, et al. Common evolutionary origin of aquareoviruses and orthoreoviruses revealed by genome characterization of Golden shiner reovirus, Grass carp reovirus, Striped bass reovirus and golden ide reovirus (genus Aquareovirus, family Reoviridae) J Gen Virol. 2002;83:1941–51. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-8-1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stins MF, Gilles F, Kim KS. Selective expression of adhesion molecules on human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;76:81–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mainou BA, Dermody TS. Transport to late endosomes is required for efficient reovirus infection. J Virol. 2012;86:8346–58. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00100-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Virgin HWt, Bassel-Duby R, Fields BN, Tyler KL. Antibody protects against lethal infection with the neurally spreading reovirus type 3 (Dearing) J Virol. 1988;62:4594–604. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4594-4604.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kobayashi T, et al. A plasmid-based reverse genetics system for animal double-stranded RNA viruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:147–57. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Furlong DB, Nibert ML, Fields BN. Sigma 1 protein of mammalian reoviruses extends from the surfaces of viral particles. J Virol. 1988;62:246–56. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.1.246-256.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parker JS, Broering TJ, Kim J, Higgins DE, Nibert ML. Reovirus core protein mu2 determines the filamentous morphology of viral inclusion bodies by interacting with and stabilizing microtubules. J Virol. 2002;76:4483–96. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4483-4496.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mainou BA, et al. Reovirus cell entry requires functional microtubules. MBio. 2013;4:e00405–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00405-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Becker MM, et al. Reovirus σNS protein is required for nucleation of viral assembly complexes and formation of viral inclusions. Journal of Virology. 2001;75:1459–1475. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1459-1475.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–82. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mainou BA, Dermody TS. Src kinase mediates productive endocytic sorting of reovirus during cell entry. J Virol. 2011;85:3203–13. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02056-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Becker MM, Peters TR, Dermody TS. Reovirus sigma NS and mu NS proteins form cytoplasmic inclusion structures in the absence of viral infection. Journal of Virology. 2003;77:5948–63. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.10.5948-5963.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barton ES, Connolly JL, Forrest JC, Chappell JD, Dermody TS. Utilization of sialic acid as a coreceptor enhances reovirus attachment by multistep adhesion strengthening. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:2200–2211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fontana J, Lopez-Montero N, Elliott RM, Fernandez JJ, Risco C. The unique architecture of Bunyamwera virus factories around the Golgi complex. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2012–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hurbain I, Sachse M. The future is cold: cryo-preparation methods for transmission electron microscopy of cells. Biol Cell. 2011;103:405–20. doi: 10.1042/BC20110015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Szklarczyk D, et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D447–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Purified recombinant human TRiC is a limited resource that was provided by the Frydman Lab (Stanford University). Please contact Judith Frydman directly (jfrydman@stanford.edu) for inquiries directly related to purified human TRiC.