Abstract

Fabry disease (FD) is a genetic X-linked, multisystemic, progressive lysosomal storage disorder (LSD). Depression has emerged as a disease complication, with prevalence estimates ranging from 15 to 62%. This is a pilot study examining the effects of psychological counseling for depression in FD on depression, adaptive functioning (AF), quality of life (QOL), and subjective pain experience. Telecounseling was also piloted, as it has beneficial effects in other chronic diseases which make in-person counseling problematic. Subjects completed 6 months of in-person or telecounseling with the same health psychologist, followed by 6 months without counseling. Self-report measures of depression, AF, QOL, and subjective pain were completed every 3 months. All subjects experienced improvements in depression, which were sustained during the follow-up period. Improvements in depression were correlated with improvements in mental health QOL and subjective pain severity, while improvements in mental health QOL were correlated with improvements in AF. While statistical comparison between counseling modes was not possible with the given sample size, relevant observations were noted. Recommendations for future research include replication of results with a larger sample size and a longer counseling period. The use of video counseling may be beneficial. In conclusion, the present pilot study supports the efficacy of psychological treatment for depression in people with FD, highlighting the importance of having health psychologists housed in LSD treatment centers, rather than specialty psychology/psychiatry settings, to increase participation and decrease potential obstacles to access due to perceived stigma.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this chapter (doi:10.1007/8904_2017_21) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Adaptive functioning, Depression, Fabry, Quality of life, Telecounseling

Introduction

Fabry disease (FD) is an X-linked lysosomal storage disorder (LSD) caused by mutations in the GLA gene, leading to deficiency of α-galactosidase A (α-gal A; EC 3.2.1.22) and resulting in storage of globotriaosylceramide (GL3) and related lipids in the lysosome. Incidence has historically been estimated at 1:40,000 male live births; however, recent data suggest as high as 1:3,000 (Hopkins et al. 2015), with a range of 1,250–117,000 worldwide (Laney et al. 2015). Symptoms and complications include acroparesthesia, fatigue, anhidrosis, angiokeratomas, GI symptoms, kidney failure, cardiovascular problems, and stroke (Desnick et al. 2003; MacDermot et al. 2001). Standard of care treatment is enzyme replacement therapy (ERT).

Depression is increasingly recognized as a complication of FD, with prevalence estimates ranging from 15 to 62% (Bolsover et al. 2014; Crosbie et al. 2009; Laney et al. 2013; Lhle et al. 2015; Schermuly et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2007). In the largest study (n = 296), Cole et al. (2007) reported that 46% of subjects met criteria for clinically significant depressive symptoms. Wang et al. (2007) found globally reduced quality of life (QOL) in FD women, with 62% reporting symptoms of depression and/or antidepressant treatment. While the most common factor associated with depression in FD is chronic pain (Bolsover et al. 2014; Cole et al. 2007), economic status, relationship status, and symptoms such as anhidrosis and acroparesthesia are also associated with depression and lower QOL (Cole et al. 2007; Gold et al. 2002). Lhle et al. (2015) found that antidepressants were more frequent among FD subjects than controls. Finally, FD does not follow gender norms, with males reporting greater depression than females (Cole et al. 2007; Sigmundsdottier et al. 2014).

While it is not understood whether depression is an organic symptom (Lhle et al. 2015), a result of Fabry-related cerebrovascular disease (Lhle et al. 2015), a reaction to coping with a chronic progressive condition (Campbell et al. 2003; Katon 2003), or a combination, it is clear that it needs to be taken seriously (Staretz-Chacham et al. 2010). Lhle et al. (2015) found that almost half of FD subjects reporting severe depression were undiagnosed and untreated. Few LSD centers integrate medical and psychological treatment, resulting in genetic counselors and nurses having to try to fill the psychosocial gap (Grosse et al. 2009; Hughes et al. 2006; Weber et al. 2012).

Untreated depression impacts self-management of chronic illness via negative effects on memory, energy, sense of well-being, and interpersonal interactions (Cole et al. 2007; Katon and Ciechanowski 2002). Consequences can include increased complication severity, pain intensity, and disability (Cole et al. 2007; Dersh et al. 2002; Katon 2003). Current FD treatment requires biweekly infusions, yet some patients are noncompliant despite the adverse health effects of missing infusions (West and LeMoine 2007).

While in-person psychological counseling is standard of care, telecounseling has become prevalent when in-person is not feasible. Research supports telecounseling for a range of concerns and populations (Stiles-Shields et al. 2014), including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (Hilty et al. 2013; Jenkins-Guarnieri et al. 2015; Mohr et al. 2012), as well as chronic illnesses such as HIV/AIDS (Himelhoch et al. 2013), multiple sclerosis (Mohr et al. 2005, 2007), and breast cancer (Badger et al. 2005). In such populations, telecounseling can help with barriers to in-person counseling, including physical impairments, fatigue, transportation, lack of local specialized services, childcare, stigma, and lack of finances (Mohr et al. 2005; Hollon et al. 2002). When FD treatment at an infusion center is problematic, ERT is often administered via home health nursing agencies. For these patients, telecounseling may help them receive psychological treatment at home as well.

In summary, it is critical to assess depression in FD and expand standard of care to include mental health treatment where appropriate. The present study is a first step toward focused treatment of FD-associated depression. We hypothesize that counseling will improve depression and consequently adaptive functioning (AF), subjective pain severity, and overall QOL. Furthermore, we hypothesize that telecounseling will be as effective as in-person counseling.

Methods

Subjects were recruited through Emory’s LSD Center from December 2010 through September 2013. Eligibility criteria included English-speaking individuals with FD ≥18 years old.

Subjects completed three self-report questionnaires: the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) Adult Self-Report (ASR) or Older Adult Self-Report (OASR), the Short Form 36-item Health Questionnaire (SF-36), and the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI). Subjects scoring within borderline-clinical to clinical ranges on the depression scale of the ASEBA were randomized into in-person counseling or telecounseling conditions. Any subject reporting suicidal ideation was excluded and referred to more intensive psychiatric care.

All subjects participated in counseling with the same health psychologist every 2 weeks for 6 months. Counseling was tailored to each subject’s particular situation, utilizing a combination of cognitive behavioral tools (e.g., log-keeping for identification of triggers, journaling to identify patterns in cognition, goal-setting, and homework assignments pertaining to specific stressors) and insight-oriented techniques (e.g., exploration of themes in interpersonal relationships, understanding the influence of past circumstances and coping skills on present challenges, with a focus on increasing self-awareness and decreasing cognitive dissonance). Subjects repeated ASEBA ASR or OASR, SF-36, and BPI questionnaires at 3 and 6 months in counseling, as well as at post-counseling period (9 and 12 months), to measure sustainability of changes.

Measures

The ASEBA ASR is a reliable, validated measure of social-adaptive and psychological functioning in adults aged 18–59 and the OASR is for ages 60–90+ (Achenbach and Rescorla 2003). Norms represent the mix of ethnicities, socioeconomic status, urban–rural–suburban residency, and geography within the USA. Raw scores are converted to T-scores to permit comparisons with the general population. Scale scores are normed by gender and age and categorized as normal (<93rd percentile), borderline-clinical (93rd–97th percentiles), or clinical (>97th percentile). The ASEBA is used with a wide variety of medical conditions, including cystic fibrosis, Fabry, Morquio, Turner, Williams, Angelman, and Prader–Willi syndromes (Achenbach and Rescorla 2003; Ali and Cagle 2015; Laney et al. 2010). For this study, the Depression scale and Mean Adaptive Functioning scale were used.

The BPI is a reliable, validated measure of pain severity and interference in daily life (Cleeland 2009). It yields mean Pain Severity (PS) and Pain Interference (PI) scores. PI scores consist of two dimensions (physical activity and affective) and measure how much subjects’ pain interferes with general activity, mood, walking, normal work, relationships, sleep, and enjoyment of life. The BPI has been used with a variety of medical conditions, including Fabry and other LSDs (Ali and Cagle 2015; Cleeland 2009; Laney et al. 2010).

The SF-36 is a 36-item survey measuring QOL. Scores provide summary measurements of physical and mental well-being. Raw scores are converted to T-scores and norm-based. The SF-36 is a reliable, validated questionnaire (Maruish and DeRosa 2009; Maruish and Kosinski 2009) used with a variety of medical conditions, including Fabry and other LSDs (Ali and Cagle 2015; Hoffmann et al. 2005; Laney et al. 2010; Watt et al. 2010; Weinreb et al. 2007; Wilcox et al. 2008).

Data Analysis

ASEBA raw data was entered into assessment data manager (ADM) ASEBA scoring software. Subjects with T-scores in borderline-clinical and clinical ranges were considered symptomatic in depression and/or AF. Raw data from the SF-36 was entered into QualityMetric Health Outcomes Scoring Software 4.5, which utilizes T-scores to provide overall Physical Health Summary and Mental Health Summary scores. BPI raw data was scored according to the BPI User Guide (Cleeland 2009).

Statistical significance was evaluated at the 0.05 level. Data analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (Cary, NC) and CRAN R v3.3 (Vienna, Austria). Patient demographics, treatment characteristics, and drug specifications were summarized using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages in discrete cases. Linear mixed regression models were utilized to gauge for change in measure score outcomes over patient follow-up (0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months) in the full sample, adjusted for treatment type as a covariate. Residual errors for each modeled outcome were assessed for approximate normality via histograms, boxplots, and quantile–quantile probability plots. Post hoc t-tests, from the regression models, were employed for pairwise differences at follow-up timepoints relative to baseline and 6 months, respectively. Partial Pearson correlations, controlling for treatment type, considered linear associations between outcome measures in the full sample. Regression model estimates were plotted as model-based means and 95% confidence intervals; concurrently, raw data for each measure were plotted over patient follow-up, by treatment type, for visualization of individual and treatment trends. Finally, due to small sample size, statistically significant results noted in the linear regression models were further evaluated by nonparametric, exact Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, as a supplement. Being an exploratory study, no adjustments were made to p-values for multiple comparisons.

Results

Thirty-five FD adults were screened. Nineteen met inclusion criteria; however, two subjects enrolled in another study and two elected to withdraw before beginning counseling. A total of 15 subjects were thus randomly assigned (six to in-person counseling and nine to telecounseling). However, five subjects (one from in-person counseling and four from telecounseling) withdrew prior to the 3-month timepoint. Withdrawal reasons included involuntary incarceration, disliking the telephone aspect of counseling, cessation of crisis period, and unknown. In total, ten subjects completed the study, five in each group. Due to the small number of subjects, and for purposes of statistical power, pilot analyses concentrated on all ten subjects without stratification.

Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. All subjects spoke English and reside in the USA. Ages ranged from 22 to 61 years.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics: mean (standard deviation) or frequency (percentage)

| Characteristic, N (%) | All participants, N = 10 |

|---|---|

| Mean age (years), mean (SD) | 42.1 (12.0) |

| Gender | |

| Women | 8 (80%) |

| Men | 2 (20%) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian-American | 7 (70%) |

| African-American | 1 (10%) |

| Asian-American | 1 (10%) |

| Arab-American | 1 (10%) |

| Education | |

| Less than HS | 1 (10%) |

| Completed HS | 3 (30%) |

| Completed college | 4 (40%) |

| In or completed graduate school | 2 (20%) |

| Employment | |

| Full-time worker | 4 (40%) |

| Student | 1 (10%) |

| Disabled | 4 (40%) |

| None | 1 (10%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 6 (60%) |

| Divorced | 2 (20%) |

| Widowed | 1 (10%) |

| Single | 1 (10%) |

| Medication for Fabry disease | |

| Agalsidase alpha | 6 (60%) |

| Agalsidase beta | 1 (10%) |

| AT1001 | 2 (20%) |

| None | 1 (10%) |

| Use of psychiatric medicine | |

| Yes | 4 (40%) |

| Intermittent | 2 (20%) |

| No | 4 (40%) |

Primary Results

Psychological Symptoms

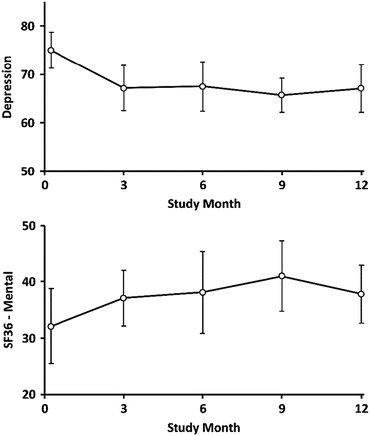

Treatment-adjusted mean summary scores and standard errors by measure over time are presented in Table 2. Subjects experienced significant improvement in depression (Mean Difference: −7.5; t(df): −2.32(16.5); p = 0.034) over the 6-month counseling period (Table 3; Fig. 1). Improvements in other variables (i.e., adaptive function, QOL, and subjective pain levels) were noted, particularly with the SF-36-Mental scale, but statistically insignificant.

Table 2.

Regression-adjusted summary scores and standard errors by measure over time

| Measure, mean (SE) | 0 months | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 10 | N = 10 | N = 10 | N = 10 | N = 10 | |

| Adjusted summaries | |||||

| Depression | 75.0 (1.9) | 67.2 (2.4) | 67.5 (2.6) | 65.7 (1.8) | 67.1 (2.5) |

| Adaptive functioning | 40.2 (2.6) | 42.0 (3.2) | 43.0 (2.5) | 42.6 (2.3) | 43.7 (3.0) |

| SF-36 – physical | 37.7 (3.2) | 38.9 (2.6) | 36.7 (2.8) | 34.4 (2.7) | 38.4 (2.5) |

| SF-36 – mental | 32.1 (3.4) | 37.1 (2.5) | 38.1 (3.7) | 41.0 (3.2) | 37.8 (2.6) |

| Pain severity score | 3.1 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.3) | 3.2 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.7) |

| Pain interference score | 4.0 (1.0) | 3.8 (0.6) | 3.4 (0.8) | 3.8 (0.9) | 3.7 (0.9) |

| PIS – physical | 3.8 (0.9) | 3.5 (0.7) | 3.3 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.6 (1.0) |

| PIS – mental | 4.3 (1.1) | 4.2 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.9) | 4.3 (1.0) | 3.9 (0.9) |

Table 3.

Regression model-based tests comparing depression scores at 6, 9, and 12 months versus baseline and 6 months, adjusted for treatment arma

| Measure | 6 months vs. baseline | 9 months vs. baseline | 12 months vs. baseline | 9 months vs. 6 months | 12 months vs. 6 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | −7.5; −2.32 (16.5); 0.034 | −9.3; −3.55 (17.5); 0.002 | −7.9; −2.49 (15.9); 0.024 | −1.8; −0.57 (15.8); 0.576 | −0.4; −0.11 (17.7); 0.914 |

aResults presented as mean measure differences relative to baseline and 6 months, respectively; t(df); p-value

Fig. 1.

Depression and SF-36-mental scores and 95% CI over follow-up visits, regression adjusted for treatment arm

Subjects’ improvement in depression was sustained over the post-counseling period; that is, depression scores at 9 months and 12 months remained significantly improved in comparison with scores at baseline (Mean Difference: −9.3 and −7.9; t(df): −3.55(17.5) and −2.49(15.9); p = 0.002 and p = 0.024, respectively). Moreover, depression scores at 9 and 12 months did not differ significantly from scores at counseling termination (Mean Difference: −1.8 and −0.4; t(df): −0.57(15.8) and −0.11(17.7); p = 0.576 and p = 0.914, respectively) (Table 3). Due to small sample size, nonparametric testing of the depression scores was also conducted and are presented in Supplementary Table 2, demonstrating analogous results. Results in the supplementary table are presented as median differences, Wilcoxon signed-rank S-statistics, and p-values.

Finally, improvement in depression correlated significantly with both mental health QOL improvement (r = 0.59; p < 0.001) and pain severity improvement (r = 0.35; p = 0.014) (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, AF correlated with both physical (r = −0.36; p = 0.010) and mental (r = 0.33; p = 0.020) components of QOL. Physical QOL was also correlated with the interference of pain in both physical (r = −0.56; p < 0.001) and mental (r = −0.39; p = 0.006) tasks (Supplementary Table 1).

Spaghetti plots by participants for each measure over time are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Quality of Life

Subjects’ scores on the SF-36 Physical Health component were not significantly different from the Mental Health component at any timepoint (Baseline: 37.7 versus 32.1, t(df): 1.2(18), p = 0.246; 3 months: 38.9 versus 37.1, t(df): 0.5(18), p = 0.624; 6 months: 36.7 versus 38.1, t(df): 0.3(18), p = 0.766; 9 months: 34.4 versus 41; t(df): 1.58(18), p = 0.132; 12 months: 38.4 versus 37.8, t(df): 0.17(18), p = 0.870). However, scores on both components were significantly lower than the US mean score of 50 at all timepoints (p-values ranged from p < 0.001 to p = 0.019). Physical and Mental Health components were not significantly correlated (Baseline: r = −0.43, p = 0.199; 3 months: r = −0.02, p = 0.962; 6 months: r = −0.37, p = 0.287; 9 months: r = 0.22, p = 0.532; 12 months: r = −0.38, p = 0.267).

Pain

Pain Severity (PS) was significantly correlated with Pain Interference (PI) at 6 months (r = 0.78, p = 0.004), 9 months (r = 0.71, p = 0.014), and 12 months (r = 0.63, p = 0.038), but not baseline (r = 0.49, p = 0.10) or 3 months (r = 0.58, p = 0.065), albeit associations at these timepoints were moderate. Correlations observed were significant for both Physical Activity (6 months: r = 0.70, p = 0.016; 9 months: r = 0.70, p = 0.017; 12 months: r = 0.65, p = 0.030) and Affective (6 months: r = 0.75, p = 0.007; 9 months: r = 0.69, p = 0.018) dimensions, relative to Pain Severity.

Discussion

The present study may be considered a pilot study demonstrating the beneficial impact of psychological counseling for FD adults with depression. Benefits included lasting improvement in depression up to 6 months post-counseling, as well as associated improvements in QOL and subjective pain severity. Improvements in mental health QOL were associated with improvements in adaptive functioning.

While statistical analysis between telecounseling and in-person counseling conditions was not possible due to sample size, a number of observational comparisons were noted. First, telecounseling subjects tended to forget and/or reschedule sessions more often than in-person subjects. As counseling occurred on infusion days for the in-person group, these subjects may have had multiple reasons to remember appointments.

Second, most subjects who withdrew came from the telecounseling group. The only in-person withdrawal was involuntary due to incarceration. Subjects who withdrew did so within the first 3 months, one verbalizing that she disliked the telecounseling aspect. It is possible that others felt similarly, but did not say so. However, at least one remaining subject verbalized, “Having someone to talk to over the phone versus in-person allowed me to feel less nervous, able to be honest. When you are on the phone, you have to talk.” This perspective mirrors Donnelly et al.’s (2000) findings with breast cancer patients that the familiar, informal nature of telephone contact led to more natural, “conversational” communications and subjects spoke more easily about intimate matters when they did not have to look the therapist in the face. Future research may differentiate characteristics regarding preference versus rejection of telecounseling more clearly.

From the psychologist’s perspective, it was more difficult to interpret subjects’ experiences without nonverbal cues or ascertain whether subjects were truly in a private place and/or engaged in other tasks rather than giving counseling their full attention. The use of video counseling may help in both regards and has been validated in populations such as PTSD (Germain et al. 2010) and geriatric depression (Choi et al. 2014a, b).

The finding that mental health QOL improvement was associated with AF improvement is important for several reasons. AF measures how effectively individuals cope with demands of everyday tasks and responsibilities. Laney et al. (2010) found AF deficits in FD patients to be higher than population norms, with poorer AF associated with greater depression, anxiety, antisocial personality, attention-deficit/hyperactivity and aggressive behavior. In comparison, only 10% of Morquio patients were observed to have mean AF deficits (Ali and Cagle 2015). While the reason for this difference is unclear, it suggests that Laney et al.’s results may be FD-specific, rather than due to chronic pain, LSD, or chronic disease in general. Our results, indicating counseling for depression in FD is associated with improved mental health QOL, which is associated with improved AF, suggest that AF may likewise be treatable via psychological counseling. While improvements in depression were not directly correlated with AF improvement, the small sample size may have prevented an effect from being realized, as counseling was not specifically for AF. Future research investigating psychological counseling for AF in FD is warranted.

Our finding that subjects’ physical and mental health QOL were both significantly below the US mean is consistent with previous FD research (Arends et al. 2015; Crosbie et al. 2009; Gold et al. 2002; Watt et al. 2010; Wilcox et al. 2008). Subjects’ improvement in QOL with counseling for depression lends credence to calls for integration of physical and psychological treatment in medical centers treating FD (Grosse et al. 2009; Hughes et al. 2006; Weber et al. 2012).

The bidirectional interaction between physical and psychological health is well-established. Biological evidence supports an overlap in the neural circuitry underlying physical and social pain (Eisenberger 2012). Multiple studies have found depression in patients with chronic illness to alter immune function, increase symptom burden and functional impairment, decrease adjustment to illness and coping skills, interfere with social functioning (e.g., irritability, withdrawal, and isolation behaviors), impede self-care and treatment compliance, and result in diminished use of the healthcare system, with resulting poorer overall medical outcomes and increased medical costs (Katon 2003; Katon and Ciechanowski 2002). On the other hand, good adjustment to illness is linked to increased attempts to gain control over one’s health and better overall health outcomes. It is thus critical to monitor depressive symptoms associated with FD and expand standard of care to include mental health treatment when necessary. As reflected in one subject’s feedback, “Counseling has made such a difference in learning to cope with chronic illness, family and work related issues. Life is very stressful in itself but learning comfortable coping tools has been the key to self-help.”

The primary study limitation is the small sample size due to the rarity of FD. A larger sample may have revealed significant differences or correlations not currently detectable, as well as permitted statistical comparisons between telecounseling and in-person conditions. In addition, subjects who participated may have differed from those who chose not to participate. Ethnic variability also differed between groups; we cannot be sure of the cause or effect of this difference. Another necessary limitation was the exclusion of subjects expressing suicidality. While it was necessary to refer these subjects to more intensive psychiatric treatment, we acknowledge that doing so restricted the subject population to mild to moderate levels of depression. While some subjects were on antidepressant medications, these subjects had all been taking these medications for long periods of time prior to the commencement of the study, suggesting that something in addition to the medication contributed to the improvements observed over the relatively short-term period of the study. Finally, while measures chosen are all well-validated, reliable measures, the use of self-report patient outcome measures may not have resulted in the same data as independent provider-rated outcome measures.

Recruitment was difficult due to several factors, including the rare nature of FD, a treatment shortage’s impact on medical center visits, and the tendency for depressed patients to be noncompliant as a consequence of depression itself (Campbell et al. 2003; Deen et al. 2013; Mohr et al. 2005). Finally, the relatively short counseling period (i.e., biweekly for 6 months, totaling approximately 12 sessions) may have been a limiting factor. Two subjects mentioned this specifically – “The only thing I would change would be ending therapy in six months. I felt alone” and “My only concern was with the time period. Just as I started to notice that the counseling was helping, that part of the study ended.”

Recommendations for future research include replication of results with a larger sample size and a longer counseling period and statistical comparison of in-person and telecounseling. The use of video counseling may also increase efficacy.

In conclusion, this pilot study supports the efficacy and need for psychological treatment for depression in people with FD, highlighting the importance of having health psychologists housed in LSD treatment centers rather than specialty psychology/psychiatry settings, to increase participation and decrease potential obstacles to access due to perceived stigma (Grosse et al. 2009; Hughes et al. 2006; Weber et al. 2012; Campbell et al. 2003).

Electronic Supplementary Material

Partial Pearson correlations, adjusted for treatment arm, across all study measures (DOCX 17 kb)

Exact, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests comparing depression response scores at 6, 9, and 12 months versus baseline and 6 months (DOCX 16 kb)

Measure spaghetti plots by participants and treatment arm (DOCX 412 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the individuals with Fabry disease who participated in this study.

This study was supported by Shire Pharmaceuticals and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR000454. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

One Sentence Take-Home Message

This study supports the efficacy of psychological counseling for depression in people with FD in improving mental health QOL.

Contributions of Individual Authors

Nadia Ali Ph.D. is responsible for conception and design of the research, data collection, data preparation and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript to be submitted for publication. She is the guarantor.

Dawn Laney M.S. is responsible for conception and design of research, securing grant funding, subject recruitment, and reviewing the article before submission for publication.

Scott Gillespie M.S. is responsible for portions of the statistical analysis, assistance writing the data analysis section of the manuscript, and construction of figures and tables.

Conflicts of Interest

Nadia Ali Ph.D. has received research support from Genzyme, Shire, BioMarin, and Pfizer, as well as lecturers’ honoraria from Genzyme, BioMarin, and Amicus. These activities are monitored and are in compliance with the conflict of interest policies at Emory University.

Dawn Laney M.S. consults for Genzyme and Shire and is a study coordinator in clinical trials sponsored by Genzyme, Amicus, and Protalix. She has also received research funding from Alexion, Amicus, Genzyme, Pfizer, Retrophin, Shire, and Synageva. These activities are monitored and are in compliance with the conflict of interest policies at Emory University.

Scott Gillespie M.S. has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Source

Shire Pharmaceuticals.

The author(s) confirm independence from the sponsors; the content of the article has not been influenced by the sponsors.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. Emory University IRB reviewed and approved the conduct of this study.

Contributor Information

Nadia Ali, Email: Nadia.Ali@emory.edu.

Collaborators: Matthias Baumgartner, Marc Patterson, Shamima Rahman, Verena Peters, Eva Morava, and Johannes Zschocke

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA adult forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ali N, Cagle S. Psychological health in adults with Morquio syndrome. JIMD Rep. 2015;20:87–93. doi: 10.1007/8904_2014_396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arends M, Hollak CEM, Biegstraaten M. Quality of life in patients with Fabry disease: a systemic review of the literature. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:77. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0296-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger T, Segrin C, Meek P, Lopez AM, Bonham E, Sieger A. Telephone interpersonal counseling with women with breast cancer – symptom management and quality of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32(2):273–279. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.273-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolsover FE, Murphy E, Cipolotti L, Werring DJ, Lachmann RH. Cognitive dysfunction and depression in Fabry disease: a systemic review. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2014;37(2):177–187. doi: 10.1007/s10545-013-9643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LC, Clauw DJ, Keefe FJ. Persistent pain and depression: a biopsychosocial perspective. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):399–409. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00545-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, Hegel MT, Marti CN, Narinucci ML, Sirrianni L, Bruce ML. Telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed low-income homebound older adults – acceptance and preliminary efficacy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2014;22(3):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, Wilson NL, Sirrianni L, Marinucci ML, Hegel MT. Acceptance of home-based telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed, low-income homebound older adults: qualitative interviews with the participants and aging-service case managers. Gerontologist. 2014;54(4):704–713. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland CS. The brief pain inventory user guide. Houston: MD Anderson Cancer Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cole AL, Lee PJ, Hughes DA, Deegan PB, Waldeck S, Lachmann RH. Depression in adults with Fabry disease: a common and underdiagnosed problem. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30:943–951. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosbie TW, Packman W, Packman S. Psychological aspects of patients with Fabry disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32:745–753. doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-1254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deen T, Fortney J, Schroeder G. Patient acceptance, initiation, and engagement in telepsychotherapy in primary care. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(4):380–384. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dersh J, Polatin PB, Gatchel RJ. Chronic pain and psychopathology: research findings and theoretical considerations. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:773–786. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000024232.11538.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desnick RJ, Brady R, Barranger J, Collins AJ, Germain DP, et al. Fabry disease, an under-recognized multisystemic disorder: expert recommendations for diagnosis, management, and enzyme replacement therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:338–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly JM, Kornblith AB, Fleishman S, Zuckerman E, Raptis G, et al. A pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy by telephone with cancer patients and their partners. Psycho-Oncol. 2000;9:44–56. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(200001/02)9:1<44::AID-PON431>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI. The pain of social disconnection: examining the shared neural underpinnings of physical and social pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(6):421–434. doi: 10.1038/nrn3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain V, Marchand A, Bouchard S, Guay S, Drouin M. Assessment of the therapeutic alliance in face-to-face or videoconference treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13(1):29–35. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold KF, Pastores GM, Botteman MF, et al. Quality of life of patients with Fabry disease. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:317–327. doi: 10.1023/A:1015511908710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse SD, Schechter MS, Kulkarni R, et al. Models of comprehensive multidisciplinary care for individuals in the United States with genetic disorders. Pediatrics. 2009;123:407–412. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilty DM, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, Johnston B, Callahan EJ, Yellowlees PM. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(6):444–454. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himelhoch S, Medoff D, Maxfield J, et al. Telephone based cognitive behavioral therapy targeting major depression among urban dwelling, low income people living with HIV/AIDS: results of a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2756–2764. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0465-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann B, Garcia de Lorenzo A, Mehta A, et al. Effects of enzyme replacement therapy on pain and health related quality of life in patients with Fabry disease: data from FOS (Fabry Outcome Survey) J Med Genet. 2005;42:247–252. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.025791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollon S, Munoz RF, Barlow DH, Beardslee WR, Bell CC, Bernal G, et al. Psychosocial intervention development for the prevention and treatment of depression: promoting innovation and increasing access. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:610–630. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins PV, Campbell C, Klug T, et al. Lysosomal storage disorder screening implementation: finding from the first six months of full population pilot testing in Missouri. J Pediatr. 2015;166(1):172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DA, Evans S, Milligan A, et al. A multidisciplinary approach to the care of patients with Fabry disease. In: Mehta A, Beck M, Sunder-Plassmann G, et al., editors. Fabry disease: perspectives from 5 years of FOS. Oxford: Oxford PharmaGenesis; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, Pruitt LD, Luxton DD, Johnson K. Patient perceptions of telemental health: systematic review of direct comparisons to in-person psychotherapeutic treatments. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21(8):1–9. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:216–226. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Ciechanowski P. Impact of major depression on chronic medical illness. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:859–863. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laney DA, Gruskin DJ, Fernhoff PM, et al. Social-adaptive and psychological functioning of patients affected by Fabry disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33(Suppl 3):S73–S81. doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-9025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laney DA, Bennett RL, Clarke V, Fox A, Hopkin RJ, Johnson J, et al. Fabry disease practice guidelines: recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns. 2013;22:555–564. doi: 10.1007/s10897-013-9613-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laney DA, Peck DS, Atherton AM, et al. Fabry disease in infancy and early childhood: a systematic literature review. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):323–330. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lhle M, Hughes D, Milligan A, et al. Clinical prodromes of neurodegeneration in Anderson-Fabry disease. Neurology. 2015;84:1454–1464. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDermot KD, Holmes A, Miners AH. Anderson-Fabry disease: clinical manifestations and impact of disease in a cohort of 60 obligate carrier females. J Med Genet. 2001;38:769–775. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.11.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruish ME, DeRosa MA. A guide to the integration of certified Short Form survey scoring and data quality evaluation capabilities. Lincoln: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maruish ME, Kosinski M. A guide to the development of certified short form interpretation and reporting capabilities. Lincoln: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Hart SL, Julian L, Catledge C, et al. Telephone-administered psychotherapy for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1007–1014. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Hart SL, Vella L. Reduction in disability in a randomized controlled trial of telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy. Health Psychol. 2007;26(5):554–563. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Ho JH, Duffecy J, Reifler D, et al. Effect of telephone-administered vs in-person cognitive behavioral therapy on adherence to therapy and depression outcomes among primary care patients. JAMA. 2012;307(21):2278–2285. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schermuly I, Muller MJ, Muller KM, Albrecht J, Keller I, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and brain structural alterations in Fabry disease. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:357–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmundsdottier L, Tchan MC, Knopman AA, Menzies GC, et al. Cognitive and psychological functioning in Fabry disease. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2014;29:642–650. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acu047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staretz-Chacham O, Choi JH, Wakabayashi K, et al. Psychiatric and behavioral manifestations of lysosomal storage disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B:1253–1265. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiles-Shields C, Kwasny MJ, Cai X, Mohr DC. Therapeutic alliance in face-to-face and telephone-administered cognitive behavioral therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:349–354. doi: 10.1037/a0035554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RY, Lelis A, Mirocha J, Wilcox WR. Heterozygous Fabry women are not just carriers, but have a significant burden of disease and impaired quality of life. Genet Med. 2007;9(1):34–45. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31802d8321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt T, Burlina AP, Cazzorla C, et al. Agalsidase beta treatment is associated with improved quality of life in patients with Fabry disease: findings from the Fabry Registry. Genet Med. 2010;12:703–712. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f13a4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber SL, Segal S, Packman W. Inborn errors of metabolism: psychosocial challenges and proposed family systems model of intervention. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;105:537–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreb N, Barranger J, Packman S, et al. Imiglucerase (Cerezyme) improves quality of life in patients with skeletal manifestations of Gaucher disease. Clin Genet. 2007;71(6):576–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West M, LeMoine K. Withdrawal of enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease: indirect evidence of treatment benefit? Mol Genet Metab. 2007;92(4):32. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.08.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox WR, Oliveira JP, Hopkin RJ, et al. Females with Fabry disease frequently have major organ involvement: lessons from the Fabry Registry. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;93:112–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Partial Pearson correlations, adjusted for treatment arm, across all study measures (DOCX 17 kb)

Exact, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests comparing depression response scores at 6, 9, and 12 months versus baseline and 6 months (DOCX 16 kb)

Measure spaghetti plots by participants and treatment arm (DOCX 412 kb)