Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG) is realised in patients with critical or advanced disease of coronary arteries. There are different pharmacotherapeutic approaches which are used as management, treatment and preventive therapy in cardiovascular disease or related comorbidities. Performing a successful surgery, pharmacotherapy, and increase of bypass patency rate remains a serious challenge.

AIM:

This study aims to analyse the patient characteristics undergoing CABG and evaluation of their drug utilisation rate and daily dosages in the perioperative period.

MATERIAL AND METHODS:

Data were collected from 102 patients in the period 2016-2017 and detailed therapeutic prescription and dosages, patient characteristics were analysed before the operation, after the operation and visit after operation in the Clinic of Cardiac surgery-University Clinical Center of Kosovo.

RESULTS:

Our findings had shown that patients provided to have normal biochemical parameters in the clinic before the operation, and were related to cardiovascular diseases and comorbidities and risk factors with mainly elective intervention. The, however, higher utilisation of cardiovascular drugs such as beta blockers, diuretics, anticoagulants, statins and lower calcium blockers, ACEi, ARBs, hydrochlorothiazide, amiodarone were founded. ARBs, beta blockers, statins, nitrates and nadroparin utilisation decreased after operation and visit after the operation, whereas amiodarone only in the visit after the operation. Diuretics are increased after the operation which decreases in the visit after the operation. Regarding the daily dosage, only metoprolol was increased in the visit after operation (P < 0.001) and visit after operation (P < 0.05) whereas losartan and furosemide were increased (P < 0.01) and (P < 0.05) respectively.

CONCLUSION:

The study showed that beta blockers, statins, aspirin, nitrates (before the operation), furosemide and spironolactone are the most utilised drugs. However, we found low utilisation rate for ACEi, ARBs, clopidogrel, nadroparin, warfarin, xanthines, amiodarone, calcium blockers. Daily dosages were different compared to before CABG only in metoprolol, losartan, and furosemide.

Keywords: Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting, Pharmacotherapy, Drug Utilization

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the biggest cause of mortality and are mostly related to the coronary heart being also higher rate cause of morbidity cross-linked with ischemic heart disease and neurologic damages from cerebral haemorrhages [1] [2] [3]. In atherosclerosis, the main mechanism of worsening of the disease remains to inflammatory processes during the atherogenesis [4]. Also, lipid deposits and oxidised phospholipids are involved in many processes such as endothelium dysfunction, activation of adhesive molecules, chemotactic factors which promote interactions between leukocytes and endothelium, tissue factor releases and activation of coagulation cascades up to atherothrombotic formation [5] [6].

Epidemiologic studies provided that diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and lifestyle with high lipid intake, stress, and sedentary life are the main triggers for the appearance of the disease [7]. Due to this pharmacotherapeutic approaches with antithrombotic, antiaggregant, hypolipidemic, anti-inflammatory, vasorelaxant, antihypertensive, percutaneous coronary interventions and cardiovascular surgeries including coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) regarding prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases, atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction and critically advanced stages of coronary artery diseases are improving [8] [9].

Patients with stenosed arteries that undergo CABG are mostly realized with saphenous vein (SV), mammary or radial artery grafts and provides improvement of angina symptoms, better quality of life and survival rates [10], while there is also difference between the type of grafts in terms of susceptibility to atherosclerosis, occlusion, and failure of grafts which mostly included SV as more sensitive to these pathophysiologic processes [11]. Therefore based on these facts among the main problems which are still appeared in patients undergoing CABG are graft failure and occlusion also related with the atherothrombotic formation, increased vasospastic agents which play a role in early and late phases of these interventions [12] [13]. The survival rate is higher in left internal mammary artery grafts and radial artery [14] [15].

There are different study approaches regarding management of perioperative symptoms and diseases by interfering in graft tissues pathophysiology which increase CABG patency rate and reduce operation complications. These groups of patients are recommended to use multiple pharmacotherapeutic agents to prevent perioperative complications [8]. Main therapies are antithrombotic, antiaggregant and anticoagulant drugs such as aspirin, clopidogrel, tirofiban, eptifibatide, enoxaparin, nadroparin, bivalirudin, fondaparinux and are limited regarding the different perioperative period due to increased risk of bleeding. Also other antihypertensive groups such as hypolipidemic including statins, beta-blockers, Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEi), Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs).

The underutilization (lower than 50 %) of these drugs in postoperative discharge have shown an increased risk of myocardial infarction and death [16] [17].

Therefore the strategies for their standardised utilisation of these drugs in CABG are essential factors to reduce the risk of coronary diseases and improving the survival rate of the patients [18]. Use of antiaggregant in the early postoperative period have improved the life expectancy of coronary bypass and cardiovascular-related symptoms, reduced graft occlusion [19], while other anticoagulants such as warfarin are shown to play a role in patients with atrial fibrillation or with thromboembolism history [20]. Statins are used unless contraindicated in patients before and after operation [21].

Beta-Blockers utilisation is found more in postoperative atrial fibrillation prevention, hypertension [22], while ACEi is used more in myocardial infarction, left ventricular dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal dysfunction. Also, calcium-blockers and diuretics are used for hypertension control.

Summarizing this number of patients affected by the cardiovascular disease in Kosovo is increasing and in particular, a considered number undergoing CABG exists. Moreover, pharmacotherapeutic evaluation is a necessary approach and intervention in perioperative procedures with the aim to reduce complications and increase the bypass patency and survival rate. Therefore, we aim to evaluate the drug utilisation rate in the perioperative state (before, after and after the visit) undergoing CABG and also identify targets for quality improvement with the preparation of guidelines and protocols for prudent use of drugs in cardiovascular surgery.

Material and Methods

This study is prospective observational study realised in 102 selected patients undergoing CABG in the period of hospitalisation in the Cardiovascular Surgery Clinic at the University Clinical Center of Kosovo (Prishtina, Kosovo) between the year 2016-2017.

The procedures in this study were conducted according to guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study design was approved by Ethics Committee in Faculty of Medicine (Nr: 3625), University of Prishtina, Hasan Prishtina and University Clinical Center of Kosovo (Pristina, Kosovo).

Patients were selected from the randomly selected subset of the study cohort to assess medication and participation were voluntary. The sample size also fits calculation of sample size was performed using Raosoft software with a 5% margin of error, a 95% confidence level, and a 50% response distribution. Since the undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting patients in Kosovo was 120-150 in previous years. In this analysed year, total numbers in this period were 134 patients in this analysed year (according to the Hospital Statistics), which are in line sample size 102. Patients with a combination of operations, the absence to visit after the operation and those that did not survive the intervention after surgery were not included in our study.

Data were collected by the clinical pharmacologist, pharmacist and cardiac surgeon with properly designed form sheet. The drug use evaluation involved the therapy prescription and daily dosages in each patient, before the operation in the clinic, in the discharge after the operation and after the first visit in the clinic (≈ 2 months). The characteristics of patients such as age, gender, related comorbidities, metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, risk factors were collected.

The number of bypass arteries or veins and priority of the intervention and available clinical indicated biochemical parameters in the period previous surgery such as Triglycerides, Cholesterol, Creatinine, AST, ALT, C-Reactive Protein (CRP), Left Ventricular Ejaculation Fraction (LVEF) were registered.

The general data’s in the tables are expressed as prevalence or mean values. Drug use and daily dosages were calculated as (%) within each group.

Two sampled t-test were used for the comparison between the data between analysed groups regarding drug utilisation, whereas One-way ANOVA for comparison between the daily therapeutic dosages from each group or unpaired student t-test for differences between the two groups.

P value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant and represented the significant differences between the analysed groups. All analysis was performed using statistical software GraphPad PRISM (version 6.0).

Results

The study included data of 102 patients, aged 62.2 ± 10.3 with woman consulting 24% of the group analysed. The comorbidities in our study were Arterial Hypertension 67%, Angina Pectoris 42%, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus 41%, Hypertriglyceridemia 21% and Hypercholesterolemia 18%. In our study, 36% were not smoking while 0-10 years smokers were 4%, 10-20 years 11%, 20-30 years 16% and 40-50 years 30%.

Indication for angiography was included in all of our analyzed patients, and there was no previous CABG found, Cerebrovascular diseases (ischaemic disease, stroke and carotid stenosis) were widespread in 6 % of patients, whereas peripheral artery diseases (microvascular and macrovascular including varicose veins) 25%, left main coronary artery occlusion was present in 15%, and 17% of patients were with post-myocardial infarction status. Chronic renal failure was only 3% patients while 10% were with low degree renal insufficiency. Based on the priority of intervention, only 18% of patients were in urgency for cardiovascular surgery whereas 85% of patients were elective cases. Graft bypass results from the left internal mammary artery and SV. Demographics and clinical characteristics regarding cardiovascular disease, comorbidities, risk factors including smoking, type of intervention, the priority of intervention and type of graft data are featured in (Table 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Demographic and Clinical Patient Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 78/24 |

| Age | 62.2 ± 10.3 |

| Angina Pectoris | 42 (%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 18 (%) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 28 (%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 41 (%) |

| Hypertension | 67 (%) |

| Smokers (before/now) | a) 0 years (36%) b) 1-10 years (4%) c) 10-20 years (11%) d) 20-30 years (16%) e) 30-40 years (30%) |

Table 2.

Patient characteristics regarding cardiovascular disorders and CABG intervention

| Cardiovascular Characteristics of Patients in CABG | |

|---|---|

| Indication for coronary angiography | 100 (%) |

| Previous CABG | 0 (%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6 (%) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 25 (%) |

| Left Main Coronary Artery Occlusion | 15 (%) |

| Status post IM | 17 (%) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 5 (%) |

| Chronic Renal Insufficiency/Renal Insufficiency | 3/10 (%) |

| CABG type (CABG Isolated/Combination) | 100/0 (%) |

| Intervention Priority (Urgency/Elective) | 18/82 (%) |

| Arteries (LIMA) Vein (VSM) for CABG (5/4/3/2) | 1/29/48/18 (%) |

Biochemical parameters and cardiovascular data were within normal range values in all investigated patients as shown in the (Table 3), even though CRP values were in borderline, the specificity also exists for in individual values with higher AST and ALT values in 11% of patients, CRP higher values in 14% of patients, Creatinine in 10% of patients (data not shown).

Table 3.

General biochemical - cardiovascular parameters of patients undergoing CABG

| Biochemical/Cardiovascular Parameters | |

|---|---|

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.83 ± 0.9 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.64 ± 1.1 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 102.9 ± 15.8 |

| AST (U/L) | 28.2 ± 12.3 |

| AST (U/L) | 31.1 ± 14.5 |

| CRP mg/dL | 6.2 ± 4.8 |

| Left Ventricular Ejaculation Fraction (%) | 53.7 ± 10.9 |

The cardiovascular system drug utilisation rates in CABG patients in the period before the operation, after operation and visit after the operation are shown in the (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cardiovascular pharmacological treatment administered in CABG Patients

| Type of Drugs | Drug Utilization Rates in CABG Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Operation (%) | After Operation (%) | Visit after Operation (%) | ||

| Beta Blockers | 77.1 | 48.2 | 59.1 | |

| Calcium Blockers | 4.9 | 9.6 | 8.1 | |

| ACEi | 31.3 | 30.1 | 23.5 | |

| ARBs | 22.9 | 3.6 | 8.5 | |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | 25.2 | 1.6 | 15.6 | |

| Furosemide | 15.7 | 97.6 | 52.8 | |

| Spironolactone | 12.2 | 91.6 | 70.1 | |

| Nitrates | 77.1 | 1.6 | 10.2 | |

| Xanthines | 7.3 | 19.3 | 7.3 | |

| Statins | 86.7 | 62.7 | 64.5 | |

| Amiodarone | 1 | 21.8 | 8.8 | |

| Digitoxin | 4.9 | 6.1 | 8.9 | |

Moreover, the other drug utilisation administered for the treatment and management of CABG patients are shown in (Table 5).

Table 5.

Other pharmacological treatment administered in CABG Patients

| Drug Utilization Rates in CABG Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Drugs | Before Operation (%) | After Operation (%) | Visit after Operation (%) |

| Warfarin | 0.5 | 4.8 | 0.5 |

| Nadroparin | 100 | 0.5 | 9.8 |

| Clopidrogrel | 0.5 | 33.8 | 21.9 |

| Aspirin | 0.5 | 97.6 | 76.5 |

| IPP | 49.4 | 65.1 | 51.8 |

| H2 Blockers | 37.4 | 35.5 | 38.5 |

| Acetaminophen | 4.8 | 35.5 | 12.2 |

| 76.5Indomethacin | 0 | 14.5 | 7.3 |

| Acetilcystine | 2.4 | 72.3 | 11.8 |

| Anxiolytics | 6.5 | 4.9 | 4.9 |

| Ceftriaxone | 14.5 | 100 | 21.1 |

| Insulins | 32.5 | 42.2 | 27.9 |

| Supplements | 1 | 33.7 | 17.7 |

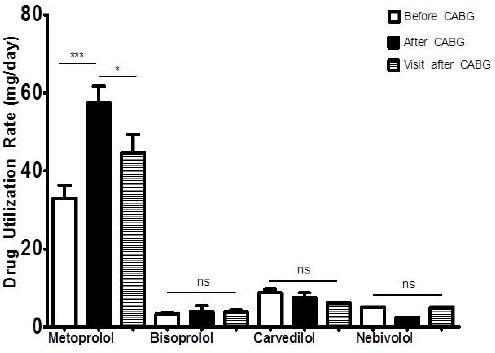

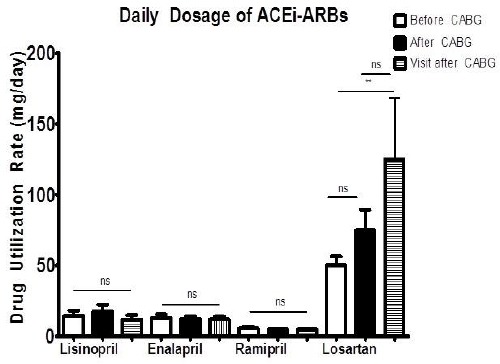

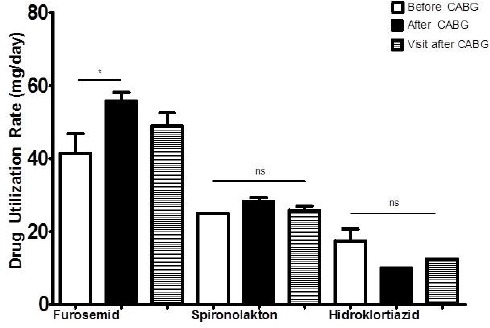

The daily dosage rates from the widely prescribed groups such as beta-blockers, ACEi, and ARBs, Diuretics are shown in (Figure 1-3).

Figure 1.

Drug Utilization Rates expressed as daily dosage (mg/day) of beta blockers: Before CABG; After CABG and Visit after CABG. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001

Figure 2.

Drug Utilization Rates expressed as daily dosage (mg/day) of ACEi/ARBs: Before CABG; After CABG and Visit after CABG. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001

Figure 3.

Drug Utilization Rates expressed as daily dosage (mg/day) of Diuretics: Before CABG; After CABG and Visit after CABG. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001

In beta blockers only metoprolol dosages are increased after the operation (P<0.001), and de-creased in the visit after operation (P<0.05) (Figure 1).

From the ACEi or ARBs, only daily dosages of losartan were increased in the visit after the operation (P<0.01) (Figure 2), whereas in diuretics furosemide dosage was increased only in the period after the operation (P<0.05) (Figure 3).

The daily dosages regarding statins, antiacids (IPP and H2 Blockers), amiodarone are within the therapeutic values, but when compared from our analysed study groups they remain to be unchanged (P>0.05) (data not shown).

Discussion

In the present study, most of the patients were affected by cardiovascular diseases and comorbidities such as angina pectoris, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and risk factors including smoking as observed in other studies [23].

Moreover, arterial diseases were also present including status post myocardial infarction, left main coronary artery occlusion, rare cases of cerebrovascular disease such as ischaemic stroke and carotid stenosis and renal failure and insufficiency. Elective patients have dominated, and SV was used more compared to a left internal mammary artery for the bypass grafting. Biochemical parameters previous intervention were within the normal ranges however there was a low number of patients which were presented with abnormal measured values. Left ventricular ejaculation fraction was standard in all analysed patients at a similar level to other reports [24] [25].

Pharmacotherapeutic evaluation has shown an increasing number of drugs in all groups corresponding three monitoring phases. The beta blockers were utilised with 77% before the operation, 48% after the operation and 59% visit after the operation. Metoprolol is the most prescribed medication with a higher dosage in the postoperative period. This data are in line with other previous findings [18]. Also, the higher utilisation in the preoperative period was shown to improve clinical outcomes by reducing the number of complications and total mortality [26]. However, there are contradictory reports in beta blockers users which showed the no beneficial effect of beta-blockers in the clinical outcomes and mortality, even though the underutilization of beta blockers (30%) were lower when compared with our data [27]. Another study performed in the larger number of patients from the national database analysis in the including no emergent and without previous MI patients showed not to be favourable in the reduction of perioperative complications. However, the preoperative utilisation rates of beta-blockers were pretty similar to our findings [28].

Additional studies with the use of the beta blockers in the secondary prevention after CABG showed lower death and myocardial infarction rate and are found to be suboptimal with reduction rate from 89 after discharge and 77% after one year [17]. Also, the higher rates of utilisation of beta-blockers have been shown in other related studies (94%) [29] [30], which are not in agreement with our data.

In continuity ACEi drug utilisation rates were (31%, 30%, and 24%) and for ARBs (23%, 4%, and 9%), hydrochlorothiazide (23%, 2%, and 16%), which show a decreasing trend in postoperative and after the first visit. Only losartan daily dosage was increased in the visit after the operation. Our data are not by previous findings which showed increased utilisation rates of the ACEi/ARBs in postoperative CABG period, even though no effect were observed regarding death and re-hospitalisation for cardiovascular events [17] [30]. Also, the pre-operative utilisation of ACEi is shown to be higher compared to our data (30% vs 50%) which still did not reflect the in the improvement of clinical outcomes or adverse events (with the only increased risk of readmission for heart failure) [31]. Moreover, in another related study, the pre-operative utilisation of ACEi was 45 % with an increased number of the major adverse events (in particular renal dysfunction and atrial fibrillation) without an impact in mortality, stroke and myocardial infarction [32].

Diuretics such as furosemide and spironolactone utilisation were increased in the period after the operation, with slowly decreasing in the visit after operation (16%, 98%, and 53%) and (12%, 92%, and 70%). The daily dosage of furosemide was increased only after the operation. Also, the diuretic use was found to be in line with our data, and increased reports of major adverse events suggest their utilisation reduction before surgery (excluding to higher clinical evidence) [33].

Moreover antiaggregant drugs such as aspirin and clopidogrel were interrupted a week before operation in all patients, hence the utilization of them were continued after operation and in the visit after operation with (98% and 77%) for aspirin, (34 and 22%) for clopidogrel which underlies that the combination of dual antiplatelet therapy was not as reported studies [27], whereas the anticoagulant therapy with nadroparin has dominated only in the period before the operation. The daily dosages were similar in all groups.

Our data are by other findings in the antiaggregant drug utilisation in related studies by showing an increased utilisation in the postoperative operative period suggesting their preventive role and lower long-term cardiovascular events [17] [34].

Utilization of hypolipidemic drugs including statins were reduced after operation (87%, 63%, and 65%) however proportional daily dosages were found, which are in line with other recommendation which emphasises their continuity in the period after operation [35].

The increased utilisation rates of statins are recommended for the further improvement of cardiovascular clinical outcomes, perioperative and postoperative complications, inflammation [36]. Their postoperative use is also shown to be higher utilised and was associated with reducing recurrent ischaemic events and mortality [17] [29] [30], which were not by our findings due to their underutilization in the period after CABG. Moreover, according to the recent study, the loading dose of statins in the period after CABG is shown to be superior to regular dose regarding cardiovascular events and without proof of serious adverse events which might reflect their strategy in the dosing guidelines and prescribing in the future [21].

Based on our findings the utilisation of aspirin, beta-blockers, statins are comparable also with other related studies while ACEi/ARBs are underutilised in our study [18]. However, our findings are in line also in the utilisation of beta blockers, aspirin, ACE, higher in statin and underutilization nitrates [37]. In another study, the secondary prevention in patients undergoing coronary bypass, the utilisation of beta blockers, aspirin, a statin was in agreement with our findings, excluding the lower rate of ACEi or ARBs [38]. Other reports after operation have shown similar trends in beta blockers, statin, with lower ACEi/ARBs which also potentiate the necessity for the optimisation of the drug use in the postoperative period [39]. A possible explanation regarding lower rates of ACEi/ARBs utilisation may be the normal values of left ventricular ejaculation fraction, even though these values were not higher as previous studies [40].

Moreover, one retrospective study was observed by providing the recorded clinical data in the period when patients were admitted and also in the discharge. In this study, the use beta blockers, aspirin, and statin were in similar range but with higher ACEi, lower ARBs (only before the operation) compared to our findings. It is worth mentioning the fact that utilisation of beta blockers, ACEi, statins were decreasing in the analysed years, and ARBs were increasing in the period before operation whereas after operation beta blockers and statins were decreasing [41].

The antiaggregants such as aspirin was regularly used and in a standard dosage and not all patients were combined with clopidogrel as dual antiplatelet.

Beta-blocker usage is in line with our data as recommended with previously reported guidelines for the pharmacotherapy after CABG [42]. However, ACEi or ARBs are not used properly in all patients due to normal LVEF in our study. Moreover, aldosterone antagonists need to be reevaluated due to their limited use in LVEF < 35% or cardiac insufficiency II-IV patients. Statin utilisation was not monitored properly and titrated in our study.

Approximate data regarding existing protocol and evidence for the management of patients after CABG are also found in other guidelines from American heart association which also relies on the type of evidence and relevant treatment [8].

Other utilised drugs in our study were: vasodilators including nitrates with (77%, 2% and 10%) and xanthines with (7%, 19% and 7%). Even though amiodarone utilisation were (1%, 18%, 7%) more should be done to replace it with beta blockers and also the use of statins with the magnesium in the same period [39]. Also, the use of amiodarone in the prevention of atrial fibrillation only 24 hours after operation intravenously and in lower dosages is another promising strategy [43].

Cardiovascular pharmacotherapeutic approaches in diabetes mellitus consisted usage of insulin which was accompanied with a reduction in the period after the operation, probably due to the increased risk of clinical features in patients with CABG [44].

Also, the antiacids such as IPP or H2 blockers are mainly used as prophylaxis regarding the surgical intervention which is a common indication [45] and decreases in the visit after the operation. Other drugs such as analgesics including acetaminophen are indicated as needed mostly in postoperative period with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs indomethacin, acetylcysteine dominated in the period after the operation and reduced in the visit after operation with also cephalosporin antibiotics. The frequency of NSAID administration after CABG has declined since the FDA recommendations and advice due to safety concerns and from 2004 (39%) to 2010 (29%) which may also impact the lower utilization in our group of patients (15%) [46], also the higher utilization of acetylcysteine need to be also considered to its scientific evidence in the prevention of atrial fibrillation to undergoing CABG patients [47].

Rare cases of digoxin, trimetazidine, tamsulosin, doxazosin, levotiroksin, fluoxetine, metformin, and ipratropium-budesonide were also founded.

In the meantime with our study regarding utilisation and daily dosages, we have also performed experimental studies for the alternative in compounds (arctigenin) for vasorelaxation and decreasing inflammation level in SV tissues [23].

In addition to this omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids were shown to be beneficial in inflammation and contractility in SV tissues [48].

There are undergoing similar approaches by other groups by investigating endothelin-1 antagonists [49], levosimendan [50], anti-ischaemic agents including ranolazine were shown to improve postoperative fibrillation in patients after CABG [40], and additional pharmacologic agents which inhibit the vasospasm of coronary grafts [51].

The drug utilisation after CABG have shown to be an important factor regarding long-term management of the clinical outcomes, the adherence of this drugs were not satisfactory after the first year after the revascularisation period [29], which suggests different strategies and interventions increase the improvements of clinical outcomes and bypass patency rates.

Despite the clinical relevance of this study, the absence of official protocols which are in the procedure of establishment to maintain effective use of drugs may affect drug prescription and utilization, long-term monitoring (more than three months) after CABG, short period of study (for 1-5 years after CABG) and the adherence monitoring after discharge including also clinical outcomes and adverse events could be considered as a limitations of our study. Taking this into consideration our work may set the stage for larger investigational studies aimed at evaluating the utilisation and also drug adherence, long-term monitoring including also the long period after the discharge and clinical outcomes and adverse events.

In summary in our study, we have found that therapeutic groups such as beta blockers, statins, aspirin, thiazides, nitrates (before the operation), furosemide and spironolactone are the most utilised drugs. However, we found low utilisation rate for ACEi, ARBs, clopidogrel, nadroparin, warfarin, xanthines, amiodarone, calcium blockers. Daily dosages were different compared to before CABG only in metoprolol, losartan, and furosemide.

Acknowledgements

This research project is part of specialisation of Armond Daci in Clinical Pharmacy sponsored by Ministry of Health in Kosovo (Nr.8359).

Footnotes

Funding: This research did not receive any financial support

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist

References

- 1.Townsend N, Wilson L, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M, Nichols M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: Epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3232–45. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw334. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw334. PMid:27523477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2011 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:4. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):e28–292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. PMid:24352519. PMCid:PMC5408159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2011;473:317–25. doi: 10.1038/nature10146. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10146. PMid:21593864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salisbury D, Bronas U. Inflammation and Immune System Contribution to the Etiology of Atherosclerosis. Nurs Res. 2014;63(5):375–85. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000053. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0000000000000053. PMid:25171563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badimon L, Vilahur G. Thrombosis formation on atherosclerotic lesions and plaque rupture. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2014;276:618–32. doi: 10.1111/joim.12296. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12296. PMid:25156650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hense HW. Risk factor scoring for coronary heart disease: Prediction algorithms need regular updating. Br Medicaj J. 2003;327(7426):1238. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7426.1238. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7426.1238. PMid:14644935. PMCid:PMC286233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, Bittl JA, Bridges CR, Byrne JG, Cigarroa JE, DiSesa VJ, Hiratzka LF, Hutter AM, Jessen ME. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;58(24):e123–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.009. PMid:22070836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cannon CP, Harrington RA, James S, Ardissino D, Becker RC, Emanuelsson H, et al. Comparison of ticagrelor with clopidogrel in patients with a planned invasive strategy for acute coronary syndromes (PLATO): a randomised double-blind study. Lancet. 2010;375(9711):283–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62191-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldman S, Zadina K, Moritz T, Ovitt T, Sethi G, Copeland JG, et al. Long-term patency of saphenous vein and left internal mammary artery grafts after coronary artery bypass surgery: Results from a Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(11):2149–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.064. PMid:15582312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim FY, Marhefka G, Ruggiero NJ, Adams S, Whellan DJ. Saphenous vein graft disease: review of pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment. Cardiol Rev. 2013;21(2):101–9. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3182736190. https://doi.org/10.1097/CRD.0b013e3182736190. PMid:22968180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foudi N, Kotelevets L, Gomez I, Louedec L, Longrois D, Chastre E, et al. Differential reactivity of human mammary artery and saphenous vein to prostaglandin E(2): implication for cardiovascular grafts. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163(4):826–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01264.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01264.x. PMid:21323896. PMCid:PMC3111684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao G, Zheng Z, Pi Y, Lu B, Lu J, Hu S. Aspirin plus clopidogrel therapy increases early venous graft patency after coronary artery bypass surgery: A single-center, randomized, controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(20):1639–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.104. PMid:21050973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harskamp RE, Lopes RD, Baisden CE, de Winter RJ, Alexander JH. Saphenous vein graft failure after coronary artery bypass surgery: pathophysiology, management, and future directions. Ann Surg. 2013;257(5):824–33. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318288c38d. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e318288c38d. PMid:23574989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu Y, Chen A, Wang Z, Liu J, Cai J, Zhou MZQ. Ten-year real-life effectiveness of coronary artery bypass using radial artery or great saphenous vein grafts in a single centre. Cardiovasc Thoratic Surg 2017. 2017 doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivx174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown C, Joshi B, Faraday N, Shah A, Yuh D, Rade JJ, et al. Emergency cardiac surgery in patients with acute coronary syndromes: A review of the evidence and perioperative implications of medical and mechanical therapeutics. Anesth Analg. 2011;112(4):777–99. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31820e7e4f. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e31820e7e4f. PMid:21385977. PMCid:PMC3063855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goyal A, Alexander JH, Hafley GE, Graham SH, Mehta RH, Mack MJ, et al. Outcomes Associated With the Use of Secondary Prevention Medications After Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(3):993–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.046. PMid:17307447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barry AR, Koshman SL, Norris CM, Ross DB, Pearson GJ. Evaluation of preventive cardiovascular pharmacotherapy after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(5):464–72. doi: 10.1002/phar.1380. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1380. PMid:24877186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams JB, DeLong ER, Peterson ED, Dokholyan RS, Ou FS, Ferguson TB. Secondary prevention after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: findings of a national randomized controlled trial and sustained society-led incorporation into practice. Circulation. 2011;123(1):39–457. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.981068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wann LS, Curtis AB, January CT, Ellenbogen KA, Lowe JE, Estes NAM, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (Updating the 2006 Guideline): A report of the American college of cardiology foundation/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123(1):104–23. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181fa3cf4. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181fa3cf4. PMid:21173346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bin C, Junsheng M, Jianqun Z, Ping B. Meta-Analysis of Medium and Long-Term Efficacy of Loading Statins After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(3):990–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.08.075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.08.075. PMid:26518376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis EM, Packard K a, Hilleman DE. Pharmacologic prophylaxis of postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: beyond beta-blockers. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:749. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.7.749. 274e–318e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daci A, Neziri B, Krasniqi S, Cavolli R, Alaj R, Norata GD, Beretta G. Arctigenin improves vascular tone and decreases inflammation in human saphenous vein. European journal of pharmacology. 2017;810:51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.06.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.06.004. PMid:28603045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee MS, Kapoor N, Jamal F, Czer L, Aragon J, Forrester J, et al. Comparison of coronary artery bypass surgery with percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47:864–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.072. PMid:16487857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johansson B, Samano N, Souza D, Bodin L, Filbey D, Mannion JD, et al. The no-touch vein graft for coronary artery bypass surgery preserves the left ventricular ejection fraction at 16 years postoperatively: long-term data from a longitudinal randomised trial. Open Hear. 2015;2(1):e000204. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000204. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2014-000204. PMid:25852948. PMCid:PMC4379882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson TB, Coombs LP, Peterson ED. Preoperative beta-blocker use and mortality and morbidity following CABG surgery in North America. JAMA. 2002;287(17):2221–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2221. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.17.2221. PMid:11980522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohsaka S, Miyata H, Motomura N, Imanaka K, Fukuda K, Kyo S, et al. Effects of preoperative β-blocker use on clinical outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting: A report from the Japanese cardiovascular surgery database. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(1):45–55. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000901. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000000901. PMid:26517856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brinkman W, Herbert MA, O’Brien S, Filardo G, Prince S, Dewey T, et al. Preoperative β-Blocker Use in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Surgery. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1320. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2356. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2356. PMid:24934977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hlatky MA, Solomon MD, Shilane D, Leong TK, Brindis R, Go AS. Use of medications for secondary prevention after coronary bypass surgery compared with percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.018. PMid:23246391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalavrouziotis D, Buth KJ, Cox JL, Baskett RJ. Should all patients be treated with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor after coronary artery bypass graft surgery? the impact of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, statins, and β-blockers after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Am Heart J. 2011;162(5):836–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.07.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2011.07.004. PMid:22093199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ouzounian M, Buth KJ, Valeeva L, Morton CC, Hassan A, Ali IS. Impact of preoperative angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use on clinical outcomes after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93(2):559–64. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.10.058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.10.058. PMid:22269723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bandeali SJ, Kayani WT, Lee V-V, Pan W, Elayda MA a, Nambi V, et al. Outcomes of Preoperative Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor Therapy in Patients Undergoing Isolated Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(7):919–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.05.021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.05.021. PMid:22727178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandeali SJ, Kayani WT, Lee VV, Elayda M, Alam M, Huang HD, et al. Association between preoperative diuretic use and in-hospital outcomes after cardiac surgery. Cardiovasc Ther. 2013;31(5):291–7. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12024. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-5922.12024. PMid:23517524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansen KH, Hughes P, Steinbrüchel DA. Antithrombotic- and anticoagulation regimens in OPCAB surgery. A Nordic survey. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2005;39(6):369–74. doi: 10.1080/14017430500199428. https://doi.org/10.1080/14017430500199428. PMid:16352490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kulik A, Voisine P, Mathieu P, Masters RG, Mesana TG, Le May MR, et al. Statin therapy and saphenous vein graft disease after coronary bypass surgery: analysis from the CASCADE randomized trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(4):1281–4. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.107 PMid21958773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kulik A, Ruel M. Statins and coronary artery bypass graft surgery: preoperative and postoperative efficacy and safety. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009;8(5):559–71. doi: 10.1517/14740330903188413. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740330903188413. PMid:19673591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okrainec K, Pilote L, Platt R, Eisenberg MJ. Use of cardiovascular medical therapy among patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: results from the ROSETTA-CABG registry. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22(10):841–7. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70302-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0828-282X(06)70302-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turley AJ, Roberts AP, Morley R, Thornley AR, Owens WA, de Belder M. Secondary prevention following coronary artery bypass grafting has improved but remains sub-optimal: the need for targeted follow-up. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2008;7(2):231–4. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2007.168948. https://doi.org/10.1510/icvts.2007.168948. PMid:18234766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alburikan KA, Nazer RI. Use of the guidelines directed medical therapy after coronary artery bypass graft surgery in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2017;25(6):819–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2016.12.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2016.12.007. PMid:28951664. PMCid:PMC5605885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krzych LJ. Treatment of hypertension in patients undergoing coronary artery by-pass grafting. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2012;12(2):127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2012.01.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2012.01.008. PMid:22342165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szychta W, Majstrak F, Opolski G, Filipiak KJ. Trends in pharmacological therapy of patients referred for coronary artery bypass grafting between 2004 and 2008: A single-centre study. Kardiologia Polska. 2015;73:1317–26. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2015.0094. https://doi.org/10.5603/KP.a2015.0094. PMid:25987400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kulik A, Ruel M, Jneid H, Ferguson TB, Hiratzka LF, Ikonomidis JS, et al. Secondary prevention after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(10):927–64. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000182. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000182. PMid:25679302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esmail M, Nilufar D, Majid GE, Reza TN, Abolfazl MME, et al. Prophylactic effect of amiodarone in atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery;a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trail. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2015;6(1):12–7. https://doi.org/10.5530/jcdr.2015.1.2. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Munnee K, Bundhun PK, Quan H, Tang Z. Comparing the Clinical Outcomes Between Insulin-treated and Non-insulin-treated Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus After Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(10):e3006. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003006. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000003006. PMid:26962814. PMCid:PMC4998895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oh AL, Tan AG, Phan HS, Lee BC, Jumaat N, Chew SP, et al. Indication of acid suppression therapy and predictors for the prophylactic use of proton-pump inhibitors vs. histamine-2 receptor antagonists in a Malaysian tertiary hospital. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2015;13(3):633–633. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2015.03.633. https://doi.org/10.18549/PharmPract.2015.03.633. PMid:26445624. PMCid:PMC4582748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kulik A, Bykov K, Choudhry NK, Bateman BT. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug administration after coronary artery bypass surgery: Utilization persists despite the boxed warning. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(6):647–53. doi: 10.1002/pds.3788. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.3788. PMid:25907164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker WL, Anglade MW, Baker EL, White CM, Kluger J, Coleman CI. Use of N-acetylcysteine to reduce post-cardiothoracic surgery complications: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2009;35:521–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.11.027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.11.027. PMid:19147369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daci A, Özen G, Uyar İ, Civelek E, Yildirim Fİ, Durman DK, Teskin Ö, Norel X, Uydeş-Doğan BS, Topal G. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids reduce vascular tone and inflammation in human saphenous vein. Prostaglandins & other lipid mediators. 2017;133:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2017.08.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2017.08.007. PMid:28838848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jeremy JY, Shukla N, Angelini GD, Wan S. Endothelin-1 (ET-1) and vein graft failure and the therapeutic potential of ET-1 receptor antagonists. Pharmacological Research. 2011;63:483–9. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.10.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2010.10.018. PMid:21056670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Toller W, Heringlake M, Guarracino F, Algotsson L, Alvarez J, Argyriadou H, et al. Preoperative and perioperative use of levosimendan in cardiac surgery: European expert opinion. International Journal of Cardiology. 2015;184:323–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.02.022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.02.022. PMid:25734940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trivedi C, Upadhyay A, Solanki K. Efficacy of ranolazine in preventing atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery: Results from a meta-analysis. Journal of Arrhythmia. 2017;33:161–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joa.2016.10.563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joa.2016.10.563. PMid:28607609. PMCid:PMC5459427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]