Abstract

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is a lung cancer histological subtype unusual in its favorable response to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Life-threatening manifestations at presentation are rarely reported and should be an important clinical concern. We report a case of a 63-year-old man presenting with rapid-onset refractory severe thrombocytopenia, development of massive hemoptysis, and death from respiratory failure. This case provides clinicians a reference for this unusual presentation and carries clinical implications for managing SCLC patients.

Keywords: Small cell lung carcinoma, Thrombocytopenia, Lung, Hemorrhage

1. Introduction

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) represents 15-20% of all lung cancers [1]. SCLC differs from non-small-cell lung cancer in its rapid tumor doubling time, high growth fraction, early development of widespread metastasis, and better response to platinum doublets chemotherapy. Thus chemotherapy is a treatment mainstay, even in poor Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status [2, 3]. Bone marrow involvement or paraneoplastic syndrome is common in patients with SCLC [4]. Hematologic abnormalities such as anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia are reported to be occasionally accompanied by bone marrow metastasis or paraneoplastic phenomenon [5, 6]. However, complications such as fatal hemorrhage are rarely reported. The clinical presentation can make diagnosis or treatment difficult. Herein, we report an SCLC patient who presented with rapid-onset, refractory severe thrombocytopenia and development of fatal pulmonary hemorrhage.

2. Case report

A 63-year-old man visited an outpatient clinic complaining of cough and dyspnea (Borg scale 4). He was a current smoker of 20 pack-years and denied histories of taking any medications or illness including cardiovascular, allergic, rheumatologic or respiratory diseases. A complete blood count revealed values within normal range, except for a lower value of platelet count, 91,000/mm3. Increased haziness on the lower lobe of the right lung was noted on his chest radiography.

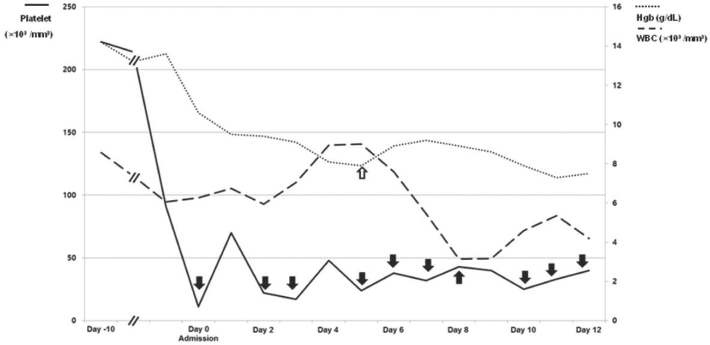

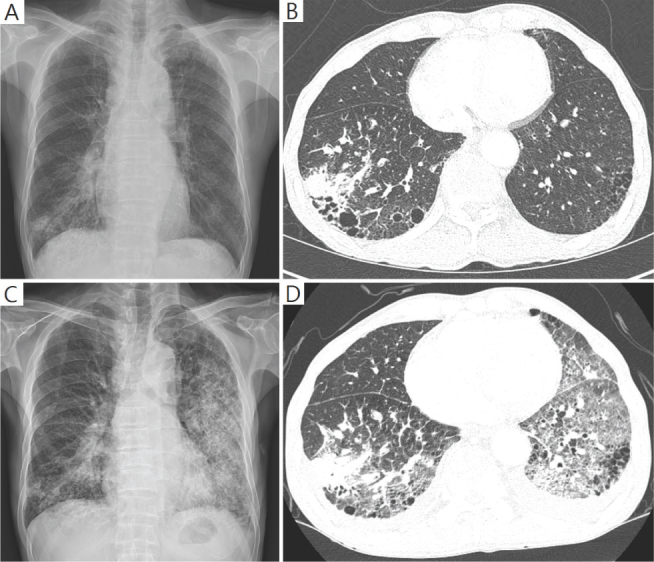

When he returned after 10 days, he was admitted with blood-tinged sputum and aggravated dyspnea (Borg scale 6). His ECOG performance status was two. He was afebrile. An arterial blood gas study revealed pH 7.44, PaCO2 37.5 mmHg, PaO2 77.6 mmHg, HCO3 25 mmol/L, and SpO2 95% on room air. Complete blood count results were as follows: leukocytes 6,270/mm3 (neutrophil 61.2%, lymphocyte 27.5%, monocyte 3.9%, eosinophil 3.9%, and basophil 0.7%), hemoglobin 10.6 g/dL, hematocrit 29.6%, and platelets 11,000/mm3. The serum lactate dehydrogenase level was 1,324 IU/L; C-reactive protein, 6.40 mg/dL. Hepatic and renal function testing were within normal range. Prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and D-dimer were within normal range as well. A 1.6 cm sized mass in the lower lobe of the right lung and multiple lymphadenopathies in mediastinal and right supraclavicular areas were noted on chest CT scan (Fig. 1). A peripheral blood smear revealed leukoerythroblastosis with nucleated erythrocyte, left shifted neutrophils. Anti-platelet antibody and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were negative. Anti-nuclear antibody was within normal range (1:20). Because of the risk of bleeding due to severe thrombocytopenia, a bronchoscopic examination was not feasible and was postponed. A bone marrow examination was not performed because the patient was unable to maintain prone position due to dyspnea. Platelet concentrates and packed red blood cells were started, given daily, and dexamethasone, 40 mg was intravenously administered for four days. However, his platelet count remained stationary (Fig. 2). On the fifth day after admission, cytological examination of his sputum yielded a diagnosis of SCLC. Metastatic lesions were not observed on brain MRI and bone scintigraphy.

Figure 1.

Newly developed diffuse ground glass opacities and consolidation in both lung fields on chest X-ray and chest CT scan at the admission (A, B) and the 7th day after (C, D).

Figure 2.

History of transfusions of platelet concentrates (black arrow) and packed red blood cells (vacant arrow) and changes in complete blood counts over the time [white blood cell (WBC), solid line; hemoglobin (Hgb), short dashed dotted line; platelet, long dashed dotted line].

On the seventh day, massive hemoptysis (≥ 200 mL per day) abruptly occurred and his dyspnea was rapidly aggravated to 8 of Borg scale. A chest CT scan revealed diffuse ground glass opacities and consolidation in both lung fields. Tranexamic acid and empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics including piperacillin-tazobactam, levofloxacin were initiated intravenously. Sputum gram stain and culture for bacteria and fungus revealed no organism. Sputum culture for adenovirus, parainfluenza virus, rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, metapneumovirus, coronavirus, bocavirus, and enterovirus were negative. Antibody studies for Mycoplasma pneumoniae and rickettsia were negative, as was an antigen study for Streptococcus pneumoniae. His arterial blood gas study showed pH of 7.49, PaCO2 of 28.7 mmHg, PaO2 of 58.3 mmHg, HCO3 22 mmol/L, and SpO2 91 % on oxygen supplied via reservoir mask flow rate 15L/min. On the tenth day, he was intubated and ventilated mechanically. He rapidly deteriorated and died of respiratory failure on the twelfth day. His family did not want to have a postmortem examination, against physician’s recommendation.

Ethical approval

The research related to human use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and in accordance the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the authors’ institutional review board or equivalent committee.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

3. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report describing an SCLC patient presenting with fatal pulmonary hemorrhage due to refractory thrombocytopenia. SCLC is the most aggressive histological subtype of lung cancer. However, favorable response is expected in 60% to 70% of patients with extensive-stage disease when systemic chemotherapy is given [3, 4]. Life-threatening manifestations rarely present in SCLC patients. When such manifestations do appear, as in the present case, the rapid-onset, unusual presentation may delay diagnosis or hesitation in deciding treatment, affecting survival adversely [7]. Therefore, prompt diagnosis and treatment is a critical issue [8].

Hematological abnormalities including anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia are commonly observed due to the toxicity of anti-cancer therapy. However, hematologic abnormalities resulting from bone marrow metastasis and paraneoplastic phenomenon are not as common as those resulting from anti-cancer therapy [5, 6]. Severe thrombocytopenia developed rapidly and was refractory to platelet transfusion and dexamethasone administration. In addition, tests for anti-platelet antibody and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were negative and anti-nuclear antibody was within normal range. These findings indicate that autoimmune disease was not likely to be the cause of thrombocytopenia [9]. Bone marrow examination is a diagnostic process for evaluating hematological abnormality or staging the disease. However, it rarely changes the stage [10] and bone marrow as an isolated metastatic site is found in fewer than 5% of SCLC patients [3]. Leukoerythroblastic reaction on peripheral blood smear is suggestive of bone marrow metastasis in the present case [11, 12]. Although bronchoscopy may be considered for localization or treatment in massive hemoptysis, it is contraindicated in a patient with severe thrombocytopenia [13].

A diagnostic and treatment plan should be determined after taking into account the benefit and risk on an individual patient basis. It is challenging to do in every possible case. The clinical presentation of the current case is unfamiliar to clinicians and rapid-onset, life threatening. However, prompt treatment with systemic chemotherapy should have been considered because he was considered fit for systemic chemotherapy by virtue of his younger age, acceptable ECOG performance status, and absence of comorbid diseases.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants (HI15C0554 and HI16C0286) from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- [1].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Elias AD. Small Cell Lung Cancer. Chest. 1997;112:251S–258S. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.4_supplement.251s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Small Cell Lung Cancer-Version 2. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jackman DM, Johnson BE. Small-cell lung cancer. The Lancet. 2005;366:1385–1396. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67569-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Khasraw M, Faraj H, Sheikha A. Thrombocytopenia in solid tumors. European journal of clinical and medical oncology. 2010;2:89–92. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ozkan M, Eser B, Er O, Coskun HS, Ozturk A, Sari I. et al. Bone marrow involvement in small cell lung cancer: prognostic significance and correlation with hematological and biochemical parameters. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;2:32–38. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Salomaa ER, Sallinen S, Hiekkanen H, Liippo K. Delays in the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer. Chest. 2005;128:2282–2288. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rice K, Schwartz SH. Lactic acidosis with small cell carcinoma. Rapid response to chemotherapy. Am J Med. 1985;79:501–503. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Krauth M-T, Puthenparambil J, Lechner K. Paraneoplastic autoimmune thrombocytopenia in solid tumors. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2012;81:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Campling B, Quirt I, DeBoer G, Feld R, Shepherd FA, Evans WK. Is bone marrow examination in small-cell lung cancer really necessary? Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:508–512. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-4-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Delsol G, Guiu-Godfrin B, Guiu M, Pris J, Corberand J, Fabre J. Leukoerythroblastosis and cancer frequency, prognosis, and physiopathologic significance. Cancer. 1979;44:1009–1013. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197909)44:3<1009::aid-cncr2820440331>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].George JN. Systemic malignancies as a cause of unexpected microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia. Oncology (Williston Park) 2011;25:908–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Du Rand IA, Blaikley J, Booton R, Chaudhuri N, Gupta V, Khalid S. et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy in adults. accredited by NICE Thorax. 2013;68(1):i1–i44. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]