Abstract

Association of dengue fever with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis in pediatric age group is a rare entity. We describe a case of 15 year old adolescent male who presented with dengue fever and in whom symptoms of transverse myelitis developed 4 weeks after fever (post-infectious stage). Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed the diagnosis of longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis involving dorso-lumbar cord. Patient recovered almost completely with minimal residual neurological deficit after a six weeks course of corticosteroids and supportive management including physiotherapy.

Keywords: Dengue fever, longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis, neurotropic virus, La fièvre de la dengue, la myélite transversale longitudinalement étendue, le virus neurotroptique

Résumé

L’association de la dengue avec une myélite transversale longitudinale étendue dans un groupe d’âge pédiatrique est une entité rare. Nous décrivons un cas d’un adolescent de 15 ans qui présentaient une dengue et chez lesquels des symptômes de myélite transversale se sont développés 4 semaines après la fièvre (stade post-infectieux). L’imagerie par résonance magnétique a confirmé le diagnostic de myélite transversale longitudinale étendue impliquant le cordon dorso-lombaire. Le patient s’est rétabli presque complètement avec un déficit neurologique résiduel minimal après un traitement de corticostéroïdes de six semaines et une prise en charge, y compris la physiothérapie.

INTRODUCTION

Dengue, an acute viral disease, transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, has a variable clinical spectrum ranging from asymptomatic infection to life-threatening dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome. Dengue virus is a cause of widespread morbidity and mortality in the tropical and subtropical areas of India.[1]

Spinal cord involvement in the form of longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) can occur in patients with dengue both during and after infection. We report a rare case of LETM in a previously healthy male child following dengue fever in postinfectious stage. The patient responded to corticosteroids and eventually had almost complete recovery with minimal residual neurological deficit.

CASE REPORT

A 15-year-old boy presented to the pediatric outpatient clinic with excruciating back pain, mainly localized in the lumbar region for 1 week. He was tossing on bed due to backache. He was unable to bear weight on his lower limbs. There were symptoms of bladder and bowel dysfunction for the last 3 days.

He was a resident of an ongoing dengue-outbreak area. He had a recent history of high-grade fever 28 days back with chills, generalized myalgia, arthralgia, headache, and petechial rash, which was diagnosed as dengue fever by serological tests. His previous records included blood investigation reports positive for nonstructural protein 1 (NS1) antigen test of dengue virus as well as decreased platelet counts documented on serial complete blood counts. HIV test was performed, which turned out to be negative.

The patient was fully conscious and oriented with preserved higher mental functions. On neurological examination, there was flaccid paralysis involving bilateral lower limbs. Muscle power in the lower limbs was 3/5 (distal more prominently involved than proximal), and generalized areflexia was evident on motor examination. Bilateral plantar reflexes were not elicitable. Abdominal reflexes were absent. There were no signs of meningeal irritation. Neurologic examination of the upper limbs and the cranial nerves was normal. Tingling sensation was present in the bilateral lower limbs.

There was no respiratory distress at the time of presentation. Other systems were completely normal. There was persistent tachycardia with a heart rate of 140–150 beats/min. Laboratory parameters showed normal complete blood picture, blood sugars, electrolytes, and kidney function test. Immunoglobulin G and M antibody test were positive for dengue.

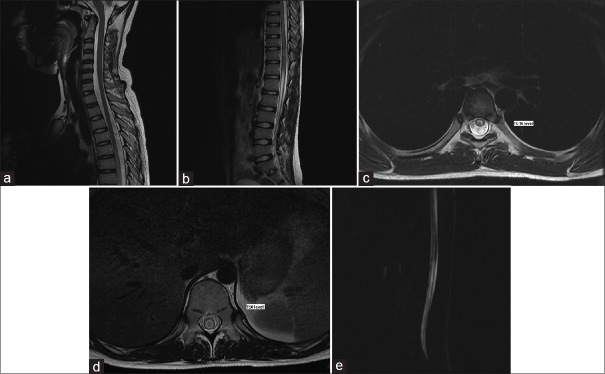

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine was done on the 2nd day of admission to exclude compressive or inflammatory disease of the spinal cord. MRI revealed continuous intramedullary T2 hyperintense signal intensity in the long segment of the dorsal and lumbar cords extending from T5 to the conus medullaris [Figure 1]. Screening MRI brain was normal.

Figure 1.

(a and b) Sagittal T2-weighted sequences covering cervical, dorsal, and lumbar cords showing continuous intramedullary T2 hyperintense signal intensity in the long segment of the dorsal and lumbar cords extending from T5 to the conus medullaris. (c) Axial T2-weighted sequences at the level of D5–D6 showing similar intramedullary T2 hyperintense signal intensity, mainly involving the central region of the cord. (d) Axial T2-weighted sequences at the level of D10 showing similar intramedullary T2 hyperintense signal intensity, mainly involving the central region of the cord. (e) Magnetic resonance myelography covering dorsolumbar region showing continuous intramedullary hyperintense signal intensity in the long segment of the dorsal and lumbar cords

A provisional diagnosis of LETM was made after considering the patient's symptoms and correlating the clinical examination findings. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis was not possible because the patient did not give consent for the lumbar puncture.

The patient was treated with analgesics and intravenous (IV) pulse therapy with methylprednisolone at a dosage of 1 g/day for 7 days and then was shifted to a regimen of oral prednisolone. The oral prednisolone dosage was started at 60 mg/day and then was tapered gradually over 6 weeks. The patient's bladder was catheterized for the first 3 days. Physical rehabilitation therapy exercises were done simultaneously with medical treatment. The weakness dramatically improved with corticosteroids, and the patient was able to walk by the 2nd week of treatment. He was discharged after 17 days of inpatient treatment, with some residual neurologic deficits. In the follow-up after 1 month, the patient had some difficulty in climbing stairs but no difficulty in walking on the floor.

Our patient had a recent history of dengue fever with rash, thrombocytopenia, and positive NS1 antigen for dengue virus. With all these features and the lack of any other important physical findings, LETM in this patient was probably the result of dengue infection. The patient responded dramatically to corticosteroid treatment with very minimal residual neurological deficit. In our patient, LETM developed in the postinfectious phase of dengue illness. The pathogenesis of myelitis in our case was likely an immune-mediated phenomenon in response to dengue virus infection.

DISCUSSION

Clinical features of dengue virus infection have been classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) according to severity as: nonspecific febrile illness, classical dengue syndrome, dengue hemorrhagic fever, and dengue shock syndrome. In 2009, the WHO reclassified clinical presentation of dengue into two entities: dengue fever ± warning signs and severe dengue. Neurological dengue is classified as a form of severe dengue.[2] However, no standardized case definitions or diagnostic criteria for neurological dengue have been agreed.

The reported incidence of neurological complications in dengue fever is <6%. Neurotropic effects of dengue virus, which was previously considered as nonneurotropic virus, have been increasingly reported in the recent years.[3] Although neurological complications in dengue fever have been documented with all serotypes, it is more common in serotypes 2 and 3.[4]

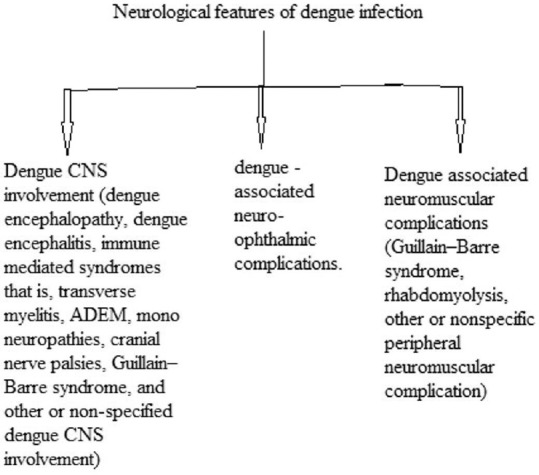

Carod-Artal et al. categorized neurological features of dengue into three types [Figure 2].[5]

Figure 2.

Categorization of neurological features of dengue by Carod-Artal et al

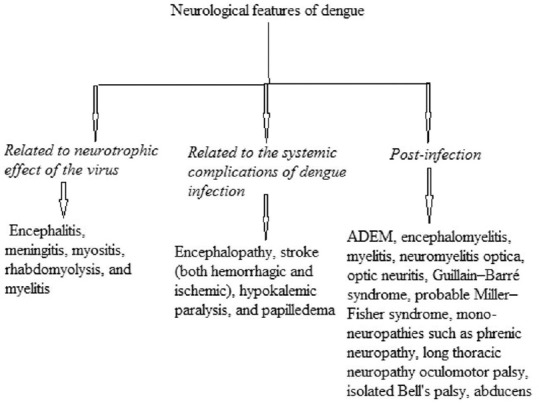

The neurological features of dengue were also grouped into three categories by Murthy [Figure 3].[6]

Figure 3.

Categorization of neurological features of dengue by Murthy

LETM can occur in patients with dengue fever either during infection (parainfectious) or after infection has subsided (postinfectious). Direct virus invasion can take place in the parainfectious stage, whereas immune-mediated factors are responsible in postinfectious phase. Postinfectious immune-mediated myelitis usually arises 1–2 weeks after the onset of initial symptoms.[7,8]

LETM refers to the involvement of three or more vertebral segments of the spinal cord by the inflammatory process which leads to severe morbidity. Full-blown disease which generally reaches within 4 weeks after onset is characterized by partial or complete paraplegia or quadriplegia with areflexia, sensory impairment, and varying degrees of bladder and bowel disturbance.[4,9]

LETM following dengue fever is very rare and reported in few case series only.[8,10,11] There is a lot of controversy regarding the treatment of transverse myelitis. Despite insufficient evidence regarding the utility of steroids in treating transverse myelitis, administration of high-dose IV methylprednisolone is typically the first treatment administered to hasten recovery and restore neurological functions. Plasma exchange may be considered the second choice. The prognosis of transverse myelitis is variable and residual symptoms are common.[12]

CONCLUSION

Even though LETM is a very rare complication of dengue fever, it is very important for the clinicians to recognize this complication and treat accordingly. MRI is an outstanding modality to diagnose any pathology in the spinal cord and rule out any compressive lesion causing similar symptoms. A high level of clinical suspicion is required along with appropriate imaging modality to diagnose this condition in patients living in or visiting dengue-endemic areas.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chaudhuri M. What can India do about dengue fever? BMJ. 2013;346:f643. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention, and Control. New edition. Geneva: TDR/World Health Organization; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendarto SK, Hadinegoro SR. Dengue encephalopathy. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1992;34:350–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1992.tb00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon T, Dung NM, Vaughn DW, Kneen R, Thao LT, Raengsakulrach B, et al. Neurological manifestations of dengue infection. Lancet. 2000;355:1053–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carod-Artal FJ, Wichmann O, Farrar J, Gascón J. Neurological complications of dengue virus infection. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:906–19. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murthy JM. Neurological complication of dengue infection. Neurol India. 2010;58:581–4. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.68654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leão RN, Oikawa T, Rosa ES, Yamaki JT, Rodrigues SG, Vasconcelos HB, et al. Isolation of dengue 2 virus from a patient with central nervous system involvement (transverse myelitis) Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2002;35:401–4. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822002000400018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seet RC, Lim EC, Wilder-Smith EP. Acute transverse myelitis following dengue virus infection. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:310–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitley JL, Leite MI, George JS, Palace JA. The differential diagnosis of longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Mult Scler. 2012;18:271–85. doi: 10.1177/1352458511406165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Sousa AM, Alvarenga MP, Alvarenga RM. A cluster of transverse myelitis following dengue virus infection in the Brazilian Amazon region. Trop Med Health. 2014;42:115–20. doi: 10.2149/tmh.2014-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larik A, Chiong Y, Lee LC, Ng YS. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis associated with dengue fever. BMJ Case Rep 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5378. pii: Bcr1220115378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lahat E, Pillar G, Ravid S, Barzilai A, Etzioni A, Shahar E. Rapid recovery from transverse myelopathy in children treated with methylprednisolone. Pediatr Neurol. 1998;19:279–82. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(98)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]