Abstract

Background:

Pain control is a vitally important goal because untreated pain has detrimental impacts on the patients as hopelessness, impede their response to treatment, and negatively affect their quality of life. Limited knowledge and negative attitudes toward pain management were reported as one of the major obstacles to implement an effective pain management among nurses. The main purpose for this study was to explore Saudi nurses’ knowledge and attitudes toward pain management.

Methods:

Cross-sectional survey was used. Three hundred knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain were submitted to nurses who participated in this study. Data were analyzed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS; version 17).

Results:

Two hundred and forty-seven questionnaires were returned response rate 82%. Half of the nurses reported no previous pain education in the last 5 years. The mean of the total correct answers was 18.5 standard deviation (SD 4.7) out of 40 (total score if all items answered correctly) with range of 3–37. A significant difference in the mean was observed in regard to gender (t = 2.55, P = 0.011) females had higher mean score (18.7, SD 5.4) than males (15.8, SD 4.4), but, no significant differences were identified for the exposure to previous pain education (P > 0.05).

Conclusions:

Saudi nurses showed a lower level of pain knowledge compared with nurses from other regional and worldwide nurses. It is recommended to considered pain management in continuous education and nursing undergraduate curricula.

Keywords: Knowledge and attitude, nursing, pain management, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Pain is a major stressor facing hospitalized patients.[1] There is a growing awareness on the etiology of pain, together with the advancement of pharmacological management of pain. Despite this awareness and pharmacological advancement, patients still experience intolerable pain which hampers the physical, emotional, and spiritual dimension of the health.[2,3] Pain control is important in the management of patients because untreated pain has a detrimental impact on the patient's quality of life.[4] Nurses spend a significant portion of their time with patients. Thus, they have a vital role in the decision-making process regarding pain management. Nurses have to be well prepared and knowledgeable on pain assessment and management techniques and should not hold false beliefs about pain management, which can lead to inappropriate and inadequate pain management practices.[5,6]

Several studies have described the barriers to delivery of an effective pain management.[4,5] Limited knowledge and negative attitude of nurses toward pain management were reported as major obstacles in the implementation of an effective pain management.[7,8] Nurses may have a negative perception, attitude, and misconception toward pain management.[6,9,10] Misconceptions include the belief that patients tend to seek attention rather report real pain, that the administration of opioids results in quick addiction, and that vital signs are the only way to reflect the presence of pain.[11] Several interventions have been attempted to address these provider-related barriers. Addressing these barriers resulted in a significant improvement in the health-care team attitudes and practice toward pain management.[5,12,13,14,15]

There is inconsistency, however, between practice and attitude, which suggests that nurses may have positive attitude toward pain management but does not have adequate knowledge to manage pain correctly and completely.[16,17] Furthermore, nurses who have low salaries and have role confusion in pain management are usually the ones who have poor knowledge of pain management.[18]

Knowledge deficit about pain management is not uncommon among health-care professionals. It is estimated that around 50% of health-care providers reported lack of knowledge in relation to pain assessment and management.[19,20] One study assessed Sri Lankan nurses’ attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge about cancer pain management and showed that poor behavior toward pain management was related to knowledge deficit and lack of authority.[21] A study on Chinese nurses showed that poor knowledge about pain management is linked with negative attitudes regarding pain management.[10] It was emphasized that an education program is effective on the nurses’ increased knowledge level and better attitudes toward pain management.[22] The practice setting influences nurses’ knowledge level of pain management. Nurses who worked in a hospice setting have relatively higher knowledge level compared with their counterparts’ who worked in district hospitals.[23]

There is a paucity of literature about nurses’ knowledge regarding pain management in the Arab world including Saudi Arabia. This study was conducted to identify nurses’ knowledge about pain management, assess nurses’ strengths and weakness in managing patients’ pain, and help nursing scholars to modify courses to improve nurses’ output regarding pain management.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in three selected hospitals that represent the health-care sector in Saudi Arabia from north, middle, and south regions in Riyadh city. All selected hospitals were referral hospitals. Nurses who work in the oncology, medical ward, surgical ward, burn units, emergency room, operation room, and Intensive Care Units in each hospital were invited to participate in this study. The researcher recruited 300 convenient nurses from the settings this number has been calculated using sample size calculator which is public service of Creative Research Systems website (Creative Research Systems, 2009).[24] Nurses who hold a degree in nursing at least agreed to participate in the study and have been working in hospitals for at least 6 months were included in this study.

A data collection sheet (DDS) was used to gather data from nurses. The DDS included questions designed to elicit information about participants’ (nurses) demographic characteristics such as sex, age, place of work, education level, previous postregistration pain education, area, and duration of clinical experience.

A knowledge and attitudes survey (KAS) section of the data collection was used to gather data about pain management. It is a 38-item questionnaire was used to assess nurses’ knowledge and attitudes toward pain management.[25] It consists of 22 “True” or “False” questions and 16 multiple-choice questions. The last two multiple choice questions were case studies. It covers areas of pain management, pain assessment, and the use of analgesics. The KAS is the only available instrument to measure nurse knowledge attitudes about pain management.[26] The KAS has an established content validity by a panel of pain experts, which was based on the American Pain Society, the World Health Organization, and the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research pain management guidelines. No permission was required to use this KAS survey tool since the authors allowed its use for research. It will be used in the English language since that nurses can understand and answer questions in English.

The recruitment of participants started with the researchers obtaining the ethical approval of the study from the Deanship of Scientific Research, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The researchers visited the hospitals and explained the study aims, procedure, and participant's role. Nurses who showed interest for the study were recruited and were asked to sign the consent form. The study questionnaire was introduced to each participant, and each participant was asked to answer the questions. Completed questionnaires were collected personally by the researchers once the participants have completed them. Then questionnaires were checked for missed items.

Data were entered and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Results are reported as numbers and percentages for categorical variables and as means and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. Independent t test was used to compare the mean total scores between gender and previous exposure to pain education. Analysis of variation (ANOVA) was used to determine the significant difference in the mean total knowledge score and educational level. Spearman correlation was used to determine the correlation between variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

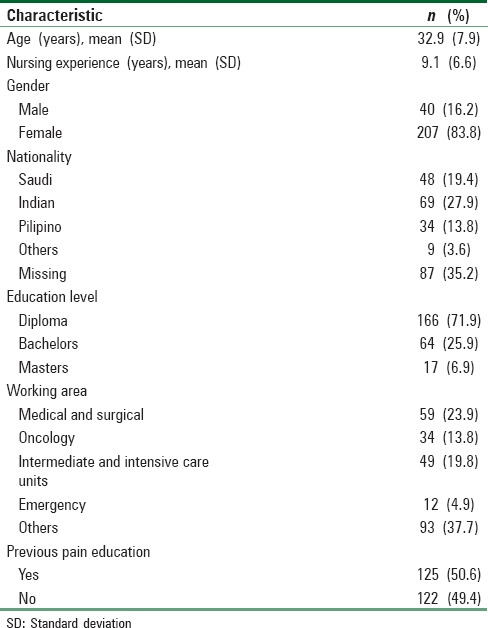

A total of 247 nurses completed and returned the study questionnaire. As shown in Table 1, 83.3% of participants were females with a mean age of 32.9 (SD 7.9) and range from 23 to 60 years. Most of the nurses had a diploma in nursing (71.9%), Indian (27.9%), and working in medical and surgical wards (23.9%). Further, 50.6% of nurses reported no previous pain education in the last 5 years.

Table 1.

Nurses demographics and professional characteristics (n=247)

Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes regarding pain management

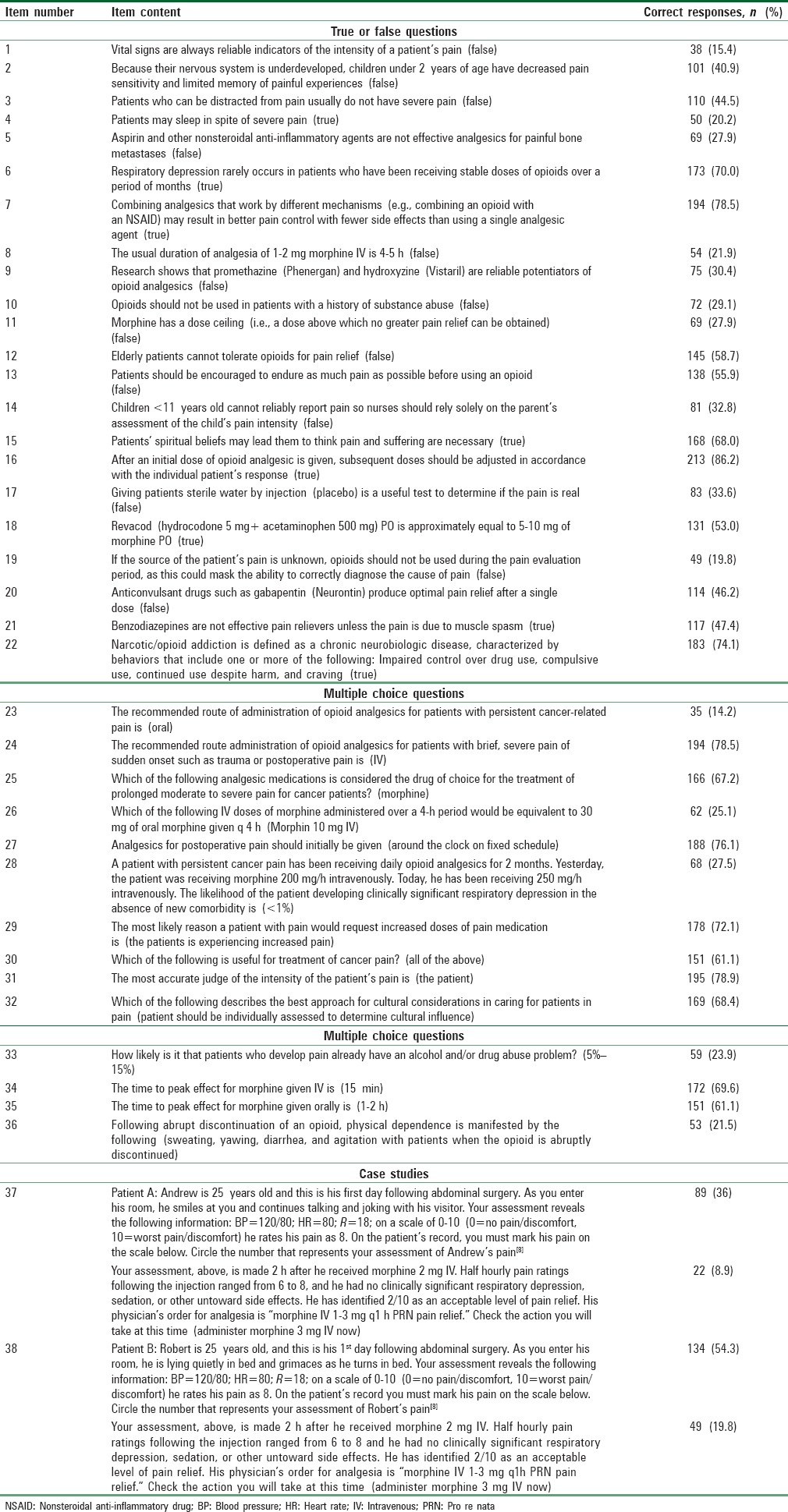

The percentages of the correctly answered items in the questionnaire are shown in Table 2. The mean of the total correct answers was 18.5 (SD 4.7) out of 40 (total score if all items answered correctly) with range of 3–37. The results show that many items were incorrectly answered and were mainly related to (a) the recommended rout of opioid administration; (b) the recommended opioid doses and the use of adjuvant medications; (c) ability to assess and reassess pain and decided on the appropriate opioids dose, (d) ability to identify signs and symptoms of addiction, tolerance, and physical dependency. Around 15.4% of the nurses failed to recognize the presence of pain because the vital signs were normal and that patients showed relaxed facial expressions. Around 15.4% of the nurses were not able to decide on which morphine dose to be used (item 38, 8.9%). Only 20% of nurses agreed that patients can sleep in spite the presence of pain. Around 78.9% of the nurses agreed that the patient is the only reliable source in reporting pain. Overall, it was found that nurses were weak in the pharmacological interventions with regard to appropriate selection, dosing, and converting between different types of opioids.

Table 2.

Correctly answered items in the questionnaire

The comparison of some questions revealed discrepancy between the nurses’ beliefs and practices. For example, 78.9% of the nurses agreed that the patient is the most reliable source for reporting pain, but 55.9% of the nurses would encourage their patient to tolerate the pain before giving them any pain medications. Furthermore, nurses were found to have negative attitude toward pain and its management. For example, only 33.6% of nurses thought that using a placebo is not useful in treating pain and 44.5% correctly knew that patients can be distracted from pain despite the presence of severe pain.

Significant differences in the mean were observed with regard to gender (t = 2.55, P = 0.011). Females had a higher mean score (18.7, SD 5.4) than males (15.8, SD 4.4). There were no significant differences in between gender with regard to the exposure to previous pain education (P > 0.05). One-way ANOVA showed no significant difference in the mean total knowledge score with regard to educational levels. Spearman's correlation test showed a positive significant relationship with years of experience (r = 0.163, P = 0.022) to the mean total knowledge and attitude score, but not for the age (r = 0.057, P = 0.487).

Discussion

The results of the current study demonstrated that the surveyed nurses had limited knowledge of pain management, and it was associated with poor attitude toward pain management. This is mainly related to their information on pharmacological pain therapy such as the use of opioids in Saudi Arabia. The average KAS score in the present study was 18.5, which was low compared to studies reported elsewhere.[27,28] The results of this study are consistent with prior studies on pain management knowledge performed in other Middle Eastern countries that nurses have limited information on the management of pain,[12,25,29] and asserted a previous assumption that nurses have poor knowledge of pain management in the KSA.[30] On the contrary, this study reported a lower percentage of correct answers in contrast to Eaton et al., who reported a higher percentage of correct answer at 73.8%.[2] A Turkish study showed nurses knowledge and attitudes using the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain (KASRP) correct rate of 35.4%, which was lower than the current study.[31] This may be due to the nursing curriculum which covers pain management in education and training. Furthermore, few participants (11.9%) attended pain management courses at their workplace. This explains the shortage of the continuing medical education courses on topics such as pain management skills and updates. Altogether, the results of this study emphasize the need for further training and education on pain management.[7]

The participating nurses in this study are typical of the workforce make up in Saudi Arabia. The participants were from diverse cultures, ethnic, religious groups, and backgrounds. There were previous studies that used KAS which focused mainly on culturally homogeneous nurse populations. Interestingly, there was a significant difference in the mean KASRP scores between the nurses from South Africa, the KSA, Middle East, Philippines, and India.[4,12,32] This variation was attributed to the cultural factors which reflected a possible variation in the level of covering pain management topics in the undergraduate education in different countries. This study, however, was not able to assess the effect of culture, ethnicity, religious background, and nationality of the participants on their knowledge of pain management.

In the current study, participants assumed that changes in vital signs represented the intensity of the experienced pain level. This faulty belief is linked with the pain assessment process, but it is not limited to the present sample of nurses. Almost one-third (32%) of the participants in a study believed that pain intensity and changes in vital signs were positively correlated.[33] Studies emphasized the importance of assessing nonverbal cues and behavioral manifestations as a pain indicator, as physiological changes in vital signs. In this sense, nurses may have thought that pain interferes with desire to sleep. The limited knowledge concerning this element was evident when (45.6%) of the participants incorrectly believed that patients can be distracted easily from pain usually do not have pain of any considerable severity.

A further area of concern in which the participants achieved low scores is in the questions on pharmacology– again. The shortfall in their knowledge seems to once again be traced to mistaken beliefs. Their misunderstanding of the pharmacology of analgesics specifically the opioids is much in line with the previous studies that identified items related to the pharmacology as vital in pain management and has therefore been given substantial significance in the KASRP survey result reporting.[4,34] This suggests that basic knowledge about pharmacological approaches is mandatory for managing pain. This study further demonstrated the lack of knowledge and the inappropriate approaches to addiction and respiratory depression originating from opioid use. The study highlighted several misconceptions about the effects of opioid analgesics. Majority of the participants (74.1%) correctly identified the definition of addiction, but they were unable to distinguish between terms such as addiction, tolerance, and physical dependence. This can be due to the variation between different patient populations and treatment regimens. It is least likely to happen when opioids are used for acute pain management specifically, and addiction to opioids is not considered to be an issue emanating from pain management of acute surgical procedures.[35] A previous study reported that only 38.1% of nurses were able to classify morphine addiction as a possibility with PRN Pro re nata (as-needed) treatment.[30] Being exposed to education sessions about pain management did not influence participants’ knowledge toward pain management, which is inconsistent with other studies which indicated the benefits of pain education courses on the nurses’ knowledge.[28,29,32]

It is clear that there is an urgent need to develop the practice knowledge of nurses with respect to pain management in Saudi Arabia. If not addressed then this could have detrimental effects on patients who are inappropriately treated. Patients’ anxiety levels may increase, and it is likely to lead patients feeling disappointed with the nursing care received. The recent trends at international level focus on integrating pain and its management to improve nurses’ knowledge and attitudes in relation to pain management. Modern programs have been implemented in Australia, the USA, and Sweden, suggesting that there is considerable room for local improvement.[36,37]

The strengths of this study include the verification of the knowledge deficit in pain management among Saudi nurses which necessitate the need for further studies. However, the study was limited by the small sample size and selection bias which resulted from the convenience sampling technique. Moreover, the design of this study was cross-sectional and the fact that some participants might not have responded to the survey.

Conclusions

This study has shown that Saudi nurses had low level of pain management knowledge and attitudes particularly in the issues related to myths of pain medication. It is recommended to considered pain management in continuous education and nursing undergraduate curricula. Moreover, further studies are needed to identify and overcome barriers of pain management among Saudi nurses and to evaluate the effectiveness of conducted pain management courses.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this work through the Research Group Project No. RG-1438-050. We are also grateful to the Vice-Deanship of Postgraduate Studies and Research at the King Saud University and the KSU Prince Sultan College of Emergency Medical Services, for the support provided to the authors of this study.

References

- 1.Ramira ML, Instone S, Clark MJ. Pediatric pain management: An evidence-based approach. Pediatr Nurs. 2016;42:39–46. 49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaton LH, Meins AR, Mitchell PH, Voss J, Doorenbos AZ. Evidence-based practice beliefs and behaviors of nurses providing cancer pain management: A mixed-methods approach. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42:165–73. doi: 10.1188/15.ONF.165-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pereira Dames LJ, Herdy Alves V, Pereira Rodrigues D, De Souza B, Rangel R, Do Valle Andrade Medeiros F, et al. Nurses’ practical knowledge on the clinical management of neonatal pain: A descriptive study. Online Brazilian J Nurs. 2016;15:393–403. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartoszczyk DA, Gilbertson-White S. Interventions for nurse-related barriers in cancer pain management. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42:634–41. doi: 10.1188/15.ONF.634-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwon JH. Overcoming barriers in cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1727–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alqahtani M, Jones LK. Quantitative study of oncology nurses’ knowledge and attitudes towards pain management in saudi arabian hospitals. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou L, Liu XL, Tan JY, Yu HP, Pratt J, Peng YQ, et al. Nurse-led educational interventions on cancer pain outcomes for oncology outpatients: A systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:218–30. doi: 10.1111/inr.12172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wengström Y, Rundström C, Geerling J, Pappa T, Weisse I, Williams SC, et al. The management of breakthrough cancer pain – Educational needs a european nursing survey. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2014;23:121–8. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eid T, Manias E, Bucknall T, Almazrooa A. Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes regarding pain in saudi arabia. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15:e25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lui LY, So WK, Fong DY. Knowledge and attitudes regarding pain management among nurses in Hong Kong medical units. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:2014–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finley GA, Forgeron P, Arnaout M. Action research: Developing a pediatric cancer pain program in Jordan. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:447–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qadire MA, Al Khalaileh MA. Effectiveness of educational intervention on Jordanian nurses’ knowledge and attitude regarding pain management. Br J Med Med Res. 2014;4:1460–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fishman SM, Young HM, Lucas Arwood E, Chou R, Herr K, Murinson BB, et al. Core competencies for pain management: Results of an interprofessional consensus summit. Pain Med. 2013;14:971–81. doi: 10.1111/pme.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lobo AD, Martins JP. Pain: Knowledge and attitudes of nursing students, 1 year follow-up. Texto Contexto Enfermagem. 2013;22:311–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tse MM, Ho SS. Enhancing knowledge and attitudes in pain management: A pain management education program for nursing home staff. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekim A, Ocakcı AF. Knowledge and attitudes regarding pain management of pediatric nurses in Turkey. Pain Manag Nurs. 2013;14:e262–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voshall B, Dunn KS, Shelestak D. Knowledge and attitudes of pain management among nursing faculty. Pain Manag Nurs. 2013;14:e226–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kassa R, Kassa G. Nurses’ attitude, practice and barriers toward cancer pain management, Addis Ababa, Ethiopian. J Cancer Sci Ther. 2014;6:483–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breivik H, Cherny N, Collett B, de Conno F, Filbet M, Foubert AJ, et al. Cancer-related pain: A pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1420–33. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saunders H. Translating knowledge into best practice care bundles: A pragmatic strategy for EBP implementation via moving postprocedural pain management nursing guidelines into clinical practice. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:2035–51. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Silva BS, Rolls C. Attitudes, beliefs, and practices of Sri Lankan nurses toward cancer pain management: An ethnographic study. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13:419–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas ML, Elliott JE, Rao SM, Fahey KF, Paul SM, Miaskowski C, et al. A randomized, clinical trial of education or motivational-interviewing-based coaching compared to usual care to improve cancer pain management. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:39–49. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.39-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson B. Nurses’ knowledge of pain. J Clin Nurs. 2011;16:1012–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creative Research Systems, Sample Size Calculator. 2009. [Last retrieved on 2017 May 10]. Available from: https://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm .

- 25.Almalki M, FitzGerald G, Clark M. The nursing profession in Saudi Arabia: An overview. Int Nurs Rev. 2011;58:304–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2011.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howell D, Butler L, Vincent L, Watt-Watson J, Stearns N. Influencing nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice in cancer pain management. Cancer Nurs. 2000;23:55–63. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200002000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Machira G, Kariuki H, Martindale L. Impact of an educational pain management programme on nurses pain knowledge and attitudes in Kenya. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2013;19:341–6. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2013.19.7.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manwere A, Chipfuwa T, Mukwamba MM, Chironda G. Knowledge and attitudes of registered nurses towards pain management of adult medical patients: A case of Bindura Hospital. Health Sci J. 2015;9:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Khawaldeh OA, Al-Hussami M, Darawad M. Knowledge and attitudes regarding pain management among Jordanian nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33:339–45. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaki AM. Medical students’ knowledge and attitude toward cancer pain management in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2011;32:628–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yildirim YK, Cicek F, Uyar M. Knowledge and attitudes of Turkish oncology nurses about cancer pain management. Pain Manag Nurs. 2008;9:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alqahtani ME. In Thesis: Examining Knowledge, Attitudes and Beliefs of Oncology Units Nurses Towards Pain Management in Saudi Arabia. Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. 2014. [Last accessed on 2017 May 10]. Available from: https://www.researchbank.rmit.edu.au/view/rmit: 161008 .

- 33.Coulling S. Doctors’ and nurses’ knowledge of pain after surgery. Nurs Stand. 2005;19:41–9. doi: 10.7748/ns2005.05.19.34.41.c3859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takai Y, Yamamoto-Mitani N, Abe Y, Suzuki M. Literature review of pain management for people with chronic pain. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2015;12:167–83. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schreiber JA, Cantrell D, Moe KA, Hench J, McKinney E, Preston Lewis C, et al. Improving knowledge, assessment, and attitudes related to pain management: Evaluation of an intervention. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15:474–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams AM, Toye C, Deas K, Fairclough D, Curro K, Oldham L, et al. Evaluating the feasibility and effect of using a hospital-wide coordinated approach to introduce evidence-based changes for pain management. Pain Manag Nurs. 2012;13:202–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borglin G, Gustafsson M, Krona H. A theory-based educational intervention targeting nurses’ attitudes and knowledge concerning cancer-related pain management: A study protocol of a quasi-experimental design. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:233. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]