Abstract

Multidrug- and colistin-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype 4,[5],12:i:- sequence type 34 is present in Europe and Asia. Using genomic surveillance, we determined that this sequence type is also endemic to Australia. Our findings highlight the public health benefits of genome sequencing–guided surveillance for monitoring the spread of multidrug-resistant mobile genes and isolates.

Keywords: Salmonella, salmonellosis, antibiotic resistance, molecular epidemiology, whole-genome sequencing, genomics, public health, bacteria, antimicrobial resistance, Australia

Since the 1990s, the global incidence of infection with Salmonella enterica serotype 4,[5],12:i:- has increased sharply among humans, livestock, and poultry (1). This monophasic variant of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium ranges from pansusceptible to multidrug resistant. In 2015, an S. enterica strain displaying the plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mcr-1 gene was discovered (2). In 2016, human and food isolates with mcr-1 were identified in Portugal (3), China (4), and the United Kingdom (5). All mcr-1–harboring isolates were predominantly Salmonella. 4,[5],12:i:- multilocus sequence typing (MLST) sequence type (ST) 34. Before this study, the ST34 clone, already emerged in Europe and Asia, was yet to be detected in Australia as a drug-resistant pathogen of humans. We therefore investigated the circulation of drug-resistant Salmonella 4,[5],12:i:- ST34 in New South Wales (NSW), Australia.

The Study

Since October 2016, all Salmonella isolates referred to the NSW Enteric Reference Laboratory (Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology Laboratory Services, Pathology West, Sydney, NSW, Australia) have undergone whole-genome sequencing in addition to serotyping and multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (MLVA) performed as described (6). Of the 971 isolates (96% from humans, 4% from food and animals) received from October 1, 2016, through March 17, 2017, a total of 80 (8.2%) were identified as Salmonella 4,[5],12:i:-, and 61 (76%) of these underwent whole-genome sequencing. Five duplicate isolates were excluded. In our retrospective study, we included 54 isolates from humans and 2 isolates from pork meat obtained from independent butchers during a routine survey conducted by the NSW Food Authority in 2016.

We extracted genomic DNA by using the chemagic Prepito-D (Perkin Elmer, Seer Green, UK) and prepared libraries by using Nextera XT kits and sequenced them on a NextSeq-500 (both by Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with at least 30-fold coverage. We assessed genomic similarity and STs by using the Nullarbor pipeline (7). We identified antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes by screening contigs through ResFinder (8) and CARD (https://card.mcmaster.ca) by using ABRicate version 0.5 (https://github.com/tseemann/abricate). Markers of colistin resistance were examined by using CLC Genomics Workbench (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA). We identified Salmonella 4,[5],12:i:- genomes recovered in Europe and Asia by using Enterobase (https://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/). We confirmed phenotypic resistance on a randomly selected subset of isolates by using the BD Phoenix system (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) or Etest (bioMérieux, Marcy L’Étoile, France).

We obtained 54 isolates from 53 case-patients who had a median age of 25 years (range <1 to 90 years). We detected 20 MLVA profiles; however, 2 profiles predominated: 3-13-10-NA-0211 (45%) and 3-13-11-NA-0211 (14%). All but 2 case-patients resided in areas of distinct postal codes distributed throughout NSW; we found no apparent temporal or geographic clustering. Recent overseas travel was reported by 5 case-patients: 2 to Cambodia and 1 each to Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia.

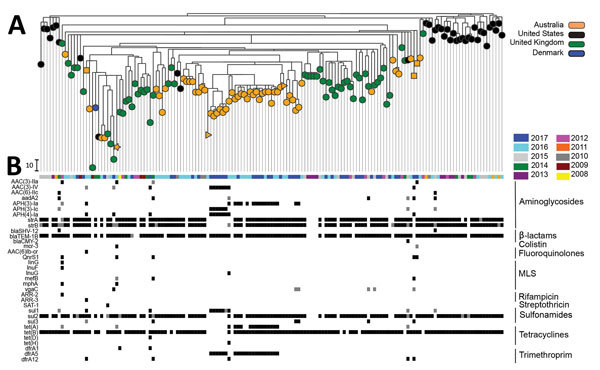

All 56 Salmonella 4,[5],12:i:- isolates were classified as ST34. The diversity between isolates was higher than that suggested by MLVA; we detected up to 112 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) differences between isolates. The isolates from Australia clustered with each other and with isolates from the United Kingdom (Figure). Combined with the steady monthly incidence of infections, these findings suggest that local circulation of Salmonella 4,[5],12:i:- might play a larger role as the source of infection than independent importations from overseas. Of note, 1 isolate from pork differed from 1 isolate from a human by only 10 SNPs, indicating that pork may be a source of human infection (Figure, panel A).

Figure.

Maximum-likelihood phylogeny of whole-genome single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of 153 Salmonella enterica 4,[5],12:i:- sequence type (ST) 34 isolates and acquired drug-resistance genes. A) SNP analysis was conducted by performing whole-genome alignment of ST34 isolates from New South Wales (NSW), Australia, and a selection of published ST34 isolates collected in the United Kingdom, United States, and Denmark by using Snippy Core (https://github.com/tseemann/snippy) (Technical Appendix). Regions of recombination were identified by using BratNextGen (www.helsinki.fi/bsg/software/BRAT-NextGen/) and removed. SNPs were identified by using SNP-sites (https://github.com/sanger-pathogens/snp-sites), and the phylogeny was generated by using FastTree (www.microbesonline.org/fasttree/). Phylogeny and antimicrobial resistance metadata were combined by using Microreact (https://microreact.org/showcase). The colistin-resistant ST34 isolate from NSW is denoted by an orange star, fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates from NSW by orange squares, and pork isolates from NSW by orange triangles. Scale bar indicates 10 SNPs. B) Year of isolation and acquisition of drug resistance. Acquired drug-resistance genes were identified by screening all isolate contigs through the ResFinder (8) and CARD (https://card.mcmaster.ca/) databases by using ABRicate version 0.5 (https://github.com/tseemann/abricate). Only genes with a 100% homology match in >1 isolate are shown. Columns depict the results for individual isolates; rows represent acquired drug-resistance genes. The antibiotic class that genes confer resistance against is indicated at right. White indicates that the specified gene was not detected, gray indicates that the specified gene was detected but sequence homology against the reference was <100%, black indicates a perfect match between the isolate and reference gene sequence. MLS, macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin B.

We detected AMR genes in 95% of ST34 isolates from NSW. The number of AMR genes (up to 13) was equivalent to that reported for ST34 isolates from the United States and United Kingdom (Figure, panel B). Of the 53 AMR isolates from NSW, 48 (90%) were classified as multidrug resistant on the basis of containing >4 AMR genes conferring resistance to different classes of antimicrobial drugs. Among the AMR isolates, 39 (73.5%) displayed multidrug resistance patterns, all of which are associated with resistance to aminoglycosides, β-lactams, and sulfonamides. A total of 21 (40%) isolates, including 1 from pork, had the core resistance-type (R-type) ASSuT (resistant to ampicillin, streptomycin, sulfonamides, and tetracycline) conferred by the strA-strB, blaTEM-1b, sul2, and tet(B) genes (Figure, panel B). This multidrug resistance pattern is characteristic of the European clone (9), which has been reported in Europe and North America and is strongly associated with pork (10,11).

R-type ASSuTTmK was found for 12 (23%) isolates from humans: genes strA-strB, aph(3′)-Ia, blaTEM-1b, tet(A)-tet(B), sul2, and dfrA5 (which confers resistance against trimethoprim). Six isolates collected from case-patients who resided in the Sydney region over a 3-week period in 2017 shared R-type ASSuTmGK: genes aac (3)-IV, aph (4)-Ia, aph(3′)-Ic, blaTEM-1B, sul1, and dfrA5 (which also confers resistance against trimethoprim) (Figure, panel B). These 6 isolates differed by 1–18 SNPs (most by <10 SNPs), and associated cases were clustered in time and occurred in neighboring suburbs, suggesting a possible cluster with a common source.

Fluoroquinolone resistance–conferring genes qnrS1 (from 3 case-patients) and aac(6′)lb-cr (from 1 case-patient) were detected (Figure, panel B). As reported previously (12), the aac(6′)lb-cr (aacA4-cr) gene was plasmid borne (IncHI2 plasmid) and was typically a class 1 integron–associated gene cassette (13). Of these 4 case-patients, 2 reported recent travel to Indonesia and Vietnam and the other 2 had no record of recent overseas travel; hence, we could not exclude the possibility of local acquisition. The isolate from the case-patient who traveled to Vietnam also displayed resistance to colistin (MIC 4 μg/mL). Neither the mcr-1 or mcr-2 genes nor mutations in the pmrAB, phoPQ, and mgrB genes were present (14). Rather, resistance was conferred by a recently identified third mobile colistin resistance gene, mcr-3, carried on a plasmid (15).

Conclusions

Using genomic surveillance, we identified the presence of novel colistin resistance gene mcr-3 and indications that multidrug-resistant Salmonella 4,[5],12:i:- ST34 has established endemicity in Australia. Our findings highlight the public health benefits of genome sequencing–guided surveillance for monitoring the spread of multidrug-resistant mobile genes and isolates.

Publicly available Salmonella sequence type 34 genomes used in study of multidrug-resistant Salmonella sequence type 34, New South Wales, Australia, 2016–2017.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NSW Food Authority and the Health Protection Branch of the NSW Ministry of Health for expert advice.

This study was funded by the NSW Department of Health through the Translational Research Grants scheme. V.S. was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship, and A.A. was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council Centre of Research Excellence in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Biography

Dr. Arnott is a postdoctoral scientist with the Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology–Public Health and Marie Bashir Institute for Infectious Diseases and Biosecurity, The University of Sydney. Her primary research interests are the molecular epidemiology and genomics of emerging and novel bacterial pathogens.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Arnott A, Wang Q, Bachmann N, Sadsad R, Biswas C, Sotomayor C, et al. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica 4,[5],12:i:- sequence type 34, New South Wales, Australia, 2016–2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018 Apr [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2404.171619

References

- 1.Switt AI, Soyer Y, Warnick LD, Wiedmann M. Emergence, distribution, and molecular and phenotypic characteristics of Salmonella enterica serotype 4,5,12:i:-. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2009;6:407–15. 10.1089/fpd.2008.0213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu Y, Liu F, Lin IY, Gao GF, Zhu B. Dissemination of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:146–7. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00533-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campos J, Cristino L, Peixe L, Antunes P. MCR-1 in multidrug-resistant and copper-tolerant clinically relevant Salmonella 1,4,[5],12:i:- and S. Rissen clones in Portugal, 2011 to 2015. Euro Surveill. 2016;21:30270. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.26.30270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li XP, Fang LX, Song JQ, Xia J, Huo W, Fang JT, et al. Clonal spread of mcr-1 in PMQR-carrying ST34 Salmonella isolates from animals in China. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38511. 10.1038/srep38511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doumith M, Godbole G, Ashton P, Larkin L, Dallman T, Day M, et al. Detection of the plasmid-mediated mcr-1 gene conferring colistin resistance in human and food isolates of Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli in England and Wales. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:2300–5. 10.1093/jac/dkw093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindstedt BA, Vardund T, Aas L, Kapperud G. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeats analysis of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium using PCR multiplexing and multicolor capillary electrophoresis. J Microbiol Methods. 2004;59:163–72. 10.1016/j.mimet.2004.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seemann T, Goncalves da Silva A, Bulach DM, Schultz MB, Kwong JC, Howden BP. Nullarbor [cited 2018 Feb 12]. https://github.com/tseemann/nullarbor

- 8.Carattoli A, Zankari E, García-Fernández A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, Villa L, et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3895–903. 10.1128/AAC.02412-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkins KL, Kirchner M, Guerra B, Granier SA, Lucarelli C, Porrero MC, et al. Multiresistant Salmonella enterica serovar 4,[5],12:i:- in Europe: a new pandemic strain? Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulvey MR, Finley R, Allen V, Ang L, Bekal S, El Bailey S, et al. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype 4,[5],12:i:- involving human cases in Canada: results from the Canadian Integrated Program on Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS), 2003-10. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:1982–6. 10.1093/jac/dkt149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.García P, Guerra B, Bances M, Mendoza MC, Rodicio MR. IncA/C plasmids mediate antimicrobial resistance linked to virulence genes in the Spanish clone of the emerging Salmonella enterica serotype 4,[5],12:i:-. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:543–9. 10.1093/jac/dkq481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robicsek A, Strahilevitz J, Jacoby GA, Macielag M, Abbanat D, Park CH, et al. Fluoroquinolone-modifying enzyme: a new adaptation of a common aminoglycoside acetyltransferase. Nat Med. 2006;12:83–8. 10.1038/nm1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Partridge SR, Tsafnat G, Coiera E, Iredell JR. Gene cassettes and cassette arrays in mobile resistance integrons. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33:757–84. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00175.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webb HE, Granier SA, Marault M, Millemann Y, den Bakker HC, Nightingale KK, et al. Dissemination of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:144–5. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00538-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin W, Li H, Shen Y, Liu Z, Wang S, Shen Z, et al. Novel plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-3 in Escherichia coli. MBio. 2017;8:e00543–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Publicly available Salmonella sequence type 34 genomes used in study of multidrug-resistant Salmonella sequence type 34, New South Wales, Australia, 2016–2017.