This cluster randomized clinical trial assesses the incidence of sexually transmitted infections in adolescents who underwent a sexual risk-reduction intervention that included content on alcohol and cannabis.

Key Points

Question

Does a behavioral intervention to reduce sexual risk among justice-involved adolescents reduce 12-month incidence of sexually transmitted infections?

Findings

In this cluster randomized clinical trial of 460 adolescents, an intervention that included alcohol- and cannabis-related content was more successful at decreasing the incidence of sexually transmitted infections than an intervention that included sexual risk reduction content alone.

Meaning

Behavioral interventions to reduce sexually transmitted infections among adolescents should include alcohol- and cannabis-related content.

Abstract

Importance

Adolescents in the juvenile justice system are at high risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Concurrent use of alcohol and cannabis increase this risk.

Objective

To determine whether a theory-based sexual risk-reduction intervention that included alcohol- and cannabis-focused content resulted in greater reductions in STIs than an intervention that included alcohol-related content only and an intervention that did not include substance use content.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Cluster randomized clinical trial with 3 conditions. Between July 1, 2010, and December 10, 2014, adolescents living at a juvenile detention facility in the southwestern United States were tested and treated for STI before randomization and again 12 months after the intervention. Data analyses were conducted in July and August 2017. Eligibility criteria included (1) being aged 14 to 18 years, (2) able to speak English, (3) having a remaining detention term of less than 1 month, and (4) signing a release granting access to STI results if tested at intake. Six hundred ninety-three adolescents were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 460 completed baseline assessments and were randomized to 1 of 3 intervention conditions. Data analysis was by intent-to-treat.

Interventions

There were 3 intervention conditions: sexual risk reduction intervention (SRRI); SRRI plus alcohol content (SRRI + ETOH); and SRRI + ETOH plus cannabis content (SRRI + ETOH + THC). Interventions were conducted in same-sex groups by trained clinicians and included video presentations with discussion, group activities, and active feedback by participants, consistent with the principles of motivational enhancement therapy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Although not the outcome on which the study was originally powered, the main outcome variable presented herein is STI incidence (Chlamydia trachomatis and/or Neisseria gonorrhoeae) 12 months after the intervention.

Results

Of the 460 participants randomized, mean (SD) age was 15.8 (1.1) years, 347 participants (75.4%) were male, and 57.0% were of Hispanic ethnicity. Among the participants, 143 were randomized to SSRI, 155 to SRRI + ETOH, and 162 to SRRI + ETOH + THC. Attrition at 12-month follow-up was 99 (21.5%) for the STI outcome variable. Participants in the SRRI + ETOH + THC intervention had lower incidence of STI at follow-up (3.9%) than those in either the SRRI (12.4%; odds ratio, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.10-0.84) or the SRRI + ETOH (10.2%; odds ratio, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.12-1.05) interventions.

Conclusions and Relevance

An intervention delivered in a motivational enhancement therapy format that includes theory-based sexual risk reduction combined with alcohol- and cannabis-focused elements is effective at reducing STI incidence among justice-involved adolescents. This 1-session manualized intervention can be delivered in the context of short-term detention and is easily disseminated to juvenile justice agencies.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01170260

Introduction

Young people aged 15 to 24 years bear a disproportionate share of the burden of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Adolescents involved in the US juvenile justice system are at increased risk for STI owing, in part, to higher rates of sexual risk behavior and alcohol and cannabis use than their non–justice-involved peers. Effective interventions are needed to assist this vulnerable population in the prevention of STI and associated complications.

It is well recognized that behavior change interventions based on behavioral science theory are more efficacious than those interventions not based on theory. Our program of research thus uses the theory of planned behavior (TPB) as the basis for the development of intervention content. The TPB posits that intentions to engage in a behavior (eg, condom use) are the most proximal determinants of behavior. Intentions, in turn, are facilitated by positive attitudes toward the behavior, perceived normative support for the behavior, and a feeling of confidence that one can engage in all the steps necessary to perform the behavior (ie, self-efficacy). A recent meta-analysis showed that in randomized controlled trials where attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy are changed, significant changes in behaviors, including risky sexual behavior, occur. Despite the many strengths of the TPB, it does not provide guidance on the optimal method of delivery of behavior change content. One validated approach to encouraging behavior change in adolescents is motivational enhancement therapy (MET), a method adapted from motivational interviewing (MI). Although there is debate about how it operates within this age group, MI and MET have both been shown to reduce substance use and risky sexual behavior in adolescents. Motivational enhancement therapy focuses on developing ambivalence, which is expected to result in participants favoring the pros over the cons of behavior change (analogous to the attitudes construct in TPB), seeing that their peers engage in and approve of behavior change (norms in TPB), and encouraging confidence in their ability to change (self-efficacy in TPB). Thus, MET may be a particularly powerful delivery method for TPB content.

Previously, two of us (A.D.B., S.J.S.) found that a didactic theory-based sexual risk-reduction intervention (SRRI) that included a segment on alcohol-focused content delivered in an MET format (SRRI + ETOH), resulted in lower rates of sexual risk behavior and higher rates of condom use compared with SRRI or an information-only control. However, outcome data were self-reported; substance use content was confounded with delivery method (SRRI was delivered in a completely didactic format, whereas SRRI + ETOH was delivered with a combination of didactic and interactive MET format); and cannabis-focused content was not included. Incorporating cannabis-focused content into the previously successful SRRI + ETOH intervention is well supported empirically and from a policy perspective given recent changes in the legalization of cannabis, decreased perceptions of its risks, and high rates of use among adolescents. In an observational longitudinal analysis, 728 adolescents (67% male) on probation were followed up for 2 years at intervals of 6 months to explore the association of cannabis use and condom use longitudinally and at a specific intercourse occasion. Results indicated that greater frequency of cannabis use at baseline was associated with a steeper decline in condom use over the 2-year study. In-depth analysis of the most recent intercourse occasion demonstrated that condom use was less likely if the participant or his or her partner was using cannabis. A recent meta-analysis summarizes existing work in this area and concludes that alcohol and cannabis use are each independently associated with risky sexual behaviors, including condomless sex and a higher number of sexual partners in adolescents. Given the links in the scientific literature between cannabis use and risky sexual behavior, we hypothesized that an intervention to reduce risky sexual behavior that included alcohol use and cannabis use content would be the most successful.

Related work in the domain of interventions to reduce sexual risk associated with substance use has often been limited methodologically by not including a comparison condition and/or by confounding content and delivery mode. Donenberg and colleagues showed promising results with a pilot intervention that targeted mental health, substance use, and sexual risk among 54 probated adolescents; however, their study lacked a control or comparison condition. Tolou-Shams et al assessed an intervention addressing the role of affect regulation and management in adolescent substance use and sexual risk among 44 adolescents from a juvenile drug court program. The affect-management intervention involved the family and the adolescent in interactive discussions, whereas the intervention that did not contain affect-management content included didactic educational content delivered only to the adolescent. The present study advances this area of research through the use of a large sample, meaningful comparison conditions, and the same delivery method (MET) in all 3 interventions; the only difference in the interventions was the presence and quantity of substance use content. Based on previous work, we hypothesized that a single-session SRRI including both alcohol- and cannabis-related content (SRRI + ETOH + THC) would lead to lower STI incidence than SRRI + ETOH or SRRI alone. Because the intervention was delivered in a group format, we evaluated this hypothesis in a cluster randomized clinical trial.

Methods

Design and Setting

The study design was a cluster randomized clinical trial. Randomization occurred at the level of small same-sex clusters. Participants completed baseline assessments before randomization using a 1:1:1 ratio into 1 of 3 same-sex group interventions: SRRI, SRRI + ETOH, or SRRI + ETOH + THC. Follow-up data were provided 12 months after the intervention. Baseline assessments and interventions were conducted at a short-term youth detention facility in the southwestern United States. All procedures were reviewed and approved by both the University of New Mexico Human Research Protections Program and, because the research involves a vulnerable population, the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Human Research Protections (the full trial protocol appears in Supplement 1). A certificate of confidentiality was also obtained from the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Adolescent assent was obtained in person and parental consent via telephone before cluster randomization. When the primary investigator (A.D.B.) moved to the University of Colorado, Boulder, during the trial, an institutional review board authorization agreement was established whereby the institutional review board of the University of Colorado, Boulder, ceded oversight to the University of New Mexico.

Sample

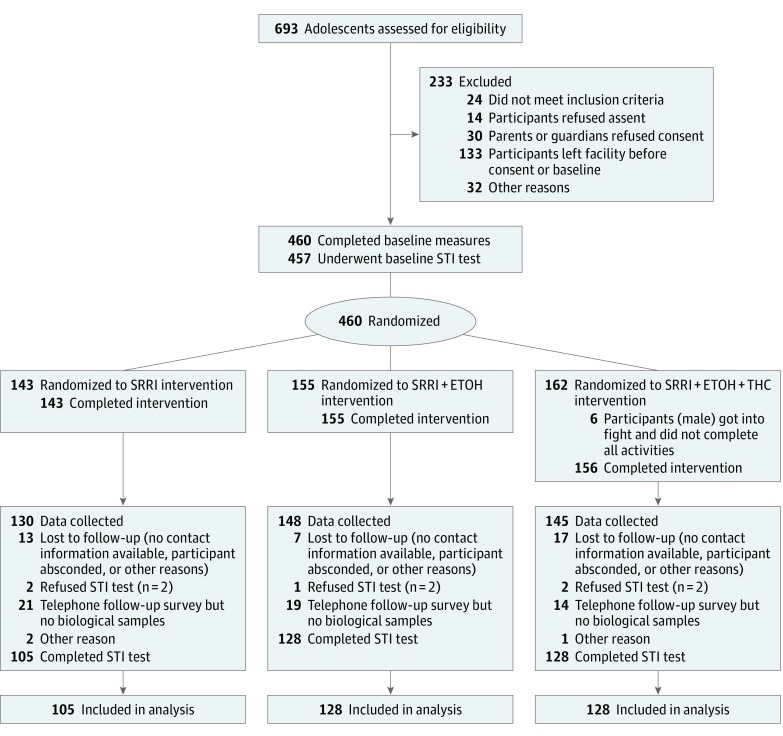

Participants were 460 adolescents residing at the detention facility at the time of recruitment. Eligibility criteria were (1) being aged 14 to 18 years, (2) being English-speaking, (3) having a remaining detention term of less than 1 month, and (4) signing a release granting access to STI results. Participants were paid $10 for baseline assessments, $20 for completing the intervention, and $50 for completing the 12-month follow-up. Figure 1 shows participant flow. Data were collected between July 1, 2010, and December 10, 2014; the trial was stopped when an adequate number of participants were recruited based on our power analyses and estimated attrition. Data analyses were conducted in July and August 2017.

Figure 1. Participant Flowchart.

SRRI indicates sexual risk reduction intervention; SRRI + ETOH, SRRI plus alcohol content; SRRI + ETOH + THC, SRRI + ETOH plus cannabis content; and STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Measurements

STI Outcomes

Urine testing (using a nucleic acid amplification test) for men and women was used to diagnose Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Participants with laboratory-confirmed C trachomatis and/or N gonorrhoeae were treated according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2010 STD Treatment Guidelines (the guidelines in effect when the trial was conducted). Directly observed therapy was provided by a medical staff member if treatment was given after baseline testing in the detention center; if treatment was given at the 12-month testing in the field, directly observed therapy was provided by a field research assistant who was supervised and trained by one of us, an adolescent medicine specialist (A.S.K.). Directly observed therapy included verifying medication allergy status, verifying the medication(s), watching the participant swallow the medication(s), educating the participant about symptoms that may indicate an adverse reaction to the medication and what to do, and observing the participant for adverse effects for 30 minutes.

Assessments

Before randomization, participants completed measures assessing demographic information, sexual history, substance use, sexual risk behavior, psychosocial history, and life history variables. Demographic items included age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Sexual history included age at first intercourse, number of unique sexual partners, lifetime and past 3 months’ frequency of condom use, and lifetime and past 3 months’ frequency of drinking or marijuana use during intercourse. Alcohol use included past 3 months’ frequency of use, frequency of getting drunk, and typical number of drinks per drinking episode. Marijuana use included age at first use and how often the participant smoked marijuana during the past 3 months. Psychosocial factors were based on the core constructs of the TPB and included assessments of attitudes toward condom use, perceived condom use norms, self-efficacy for condom use, and intention to use condoms. Finally, impulsivity was assessed with the 19-item Impulsive Sensation Seeking Scale. Our goals for these assessments were to characterize the sample, test outcomes of the intervention on self-reported sexual risk behavior, and include a range of variables that might act as moderators of our main outcomes. Questionnaires were administered via audio computer-assisted self-interviewing technology. Participants completed follow-up assessments in person at a convenient community location. These assessments included the same self-reports of the past 3 months’ sexual risk behavior and substance use as collected at baseline as well as a urine sample for STI testing and treatment following the same protocol used at baseline. Research assistants who collected follow-up data were blinded to participants’ intervention condition.

Intervention Description

There were 145 intervention groups of up to 6 participants each. Interventions took place in a single 3-hour session, approximately 2 weeks before participants’ release from detention. The study was a cluster randomized clinical trial in which randomization occurred at the level of the cluster and, because groups were all male or all female, randomization was blocked by sex. Study recruitment was on a rolling basis as adolescents entered the detention facility. Once study personnel had obtained parental consent and participant assent for a minimum of 3 adolescents, an intervention was scheduled. Condition assignment was determined via a random number list generated at study initiation by the project postdoctoral research associate, who was not involved in intervention delivery or data collection. All 3 interventions were delivered using a single-session, single-sex group format led by a master’s-level intervention leader trained in MI/MET and a trained research assistant. All interventions had identical structure and length (3 hours: 2 hours for the intervention and 1 hour for pretest and posttest assessments). In line with the principles of MI/MET, each session started with a brief introduction detailing confidentiality and its limits and establishing group rules. All elements followed the approach of MI/MET (focus on establishing common definitions and hearing the stories of the youths themselves; provision of norms; bolstering of self-affirmation; exploration of high-risk situations; and exploration of how one might change if one wanted to). Consistent with the TPB, activities were selected to increase positive attitudes toward condom use, perceived normative support for condom use, perceived behavioral control over and self-efficacy for engaging in condom use, and intention to use condoms in the future. The SRRI focused entirely on condom use. The SRRI + ETOH also targeted the role of the youth’s own alcohol use as well as his or her partner’s alcohol use in risky decision making generally and risky sexual behavior in particular. The SRRI + ETOH + THC targeted the role of the youth’s own alcohol and cannabis use as well as his or her partner’s alcohol and cannabis use in risky decision making generally and risky sexual behavior in particular. In line with MI/MET approaches more broadly and group MI/MET adolescent interventions in particular, all conditions were conducted in an MI/MET–consistent manner; that is, all content was presented and engaged in a “guiding” framework, where topics were brought up to the group by the session leader. However, most of the content was derived and discussed by the group themselves, with session leaders differentially reinforcing and emphasizing language in favor of positive health decision making (eg, more condom use, less alcohol use, and less cannabis use). All session leaders attended weekly supervision, and session content was reviewed by one of us (S.W.F.E.), an expert in MI/MET interventions, to ensure consistency with MI/MET approaches and prevent interventionist drift. Manuals were created for all 3 interventions to facilitate consistency across intervention leaders and sessions.

Statistical Analysis

Power Analysis

Biological sample collection for STI testing was added to the trial as an exploratory outcome. The trial was powered based on the primary outcomes: self-reported condom use and risky sexual behavior. Power analysis was based on a Cohen d effect size of d = 0.30 and assumed a cluster intraclass correlation of 0.05 and a 2-tailed type I error rate of 0.05. The low intraclass correlation reflected the lack of previous contact or familiarity among group participants before the single-session intervention and was based on previous empirical work in the same population. With an expected cluster size of 4, a minimum of 100 groups resulted in 80% power to detect Cohen d = 0.30 (400 total participants; approximately 133 per condition).

Data Analysis

An intent-to-treat approach was used for analyses. The STI diagnosis outcome was operationalized as a positive screening result for chlamydia and/or gonorrhea at the 12-month follow-up. This binary outcome reflecting STI diagnosis (1 = yes, 0 = no) was analyzed using a generalized mixed model with a logit link. A random effect was included to address group delivery of interventions, where cluster-level intercepts, but not cluster-level slopes, were modeled. The primary predictor was a dummy-coded intervention condition (SRRI + ETOH + THC reference). Results were interpreted as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. As an absolute measure of effect size, the risk difference was calculated as the difference between the 2 proportions for each of the 2 pairwise contrasts of interest (SRRI + ETOH + THC vs SRRI and SRRI + ETOH + THC vs SRRI + ETOH), with 95% Wald asymptotic confidence limits. Before estimating the primary model, the baseline equivalence of conditions was examined; a sensitivity analysis was conducted to address any lack of covariate balance between conditions. Potential bias due to missing data was assessed by examining the baseline covariate balance between participants retained vs those lost to follow-up. After confirming covariate balance between those retained vs lost to follow-up, complete case analysis was used as the primary data analysis approach given that the outcome reflected a medical diagnosis, but a sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation is also presented herein.

Results

The Table shows participant baseline characteristics stratified by condition. Of the 460 participants randomized, mean (SD) age was 15.8 (1.1) years, 347 (75.4%) were male, and 262 (57.0%) were of Hispanic ethnicity. Consistent with previous work in justice settings, adolescents were sexually experienced, with high levels of alcohol and cannabis use. Conditions were equivalent at baseline, with the exception of more Hispanic participants in the SRRI + ETOH group than in the SRRI + ETOH + THC group. Three hundred sixty-one participants (78.5%) contributed STI diagnosis data at the 12-month follow-up. Covariate balance was equivalent between those retained vs those lost to follow-up. Baseline characteristics of the analytic sample and covariate balance between those retained vs lost to follow-up are presented in eTables 1 and 2 in Supplement 2.

Table. Demographic, Baseline Sexual Behavior, and Substance Use Characteristics of 460 Participants Stratified by Condition.

| Characteristic | Condition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SRRI (n = 143)a | SRRI + ETOH (n = 155)a | SRRI + ETOH + THC (n = 162)a | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 15.9 (1.2) | 15.8 (1.1) | 15.8 (1.2) |

| Male, No. (%) | 105/143 (73.4) | 119/155 (76.8) | 123/162 (75.9) |

| Hispanic ethnicity, No. (%) | 83/143 (58.0) | 102/155 (65.8) | 77/162 (47.5) |

| No. of times arrested, mean (SD) | 4.2 (3.0) | 4.7 (3.5) | 4.8 (3.4) |

| Tried alcohol, No. (%) | 133/143 (93.0) | 145/155 (93.5) | 153/162 (94.4) |

| Age of first drink, mean (SD), y | 11.6 (2.4) | 12.0 (2.4) | 11.8 (2.5) |

| Tried cannabis, No. (%) | 139/143 (97.2) | 147/155 (94.8) | 153/162 (94.4) |

| Age at first cannabis use, mean (SD), y | 10.9 (2.3) | 11.2 (2.4) | 11.1 (2.4) |

| Had sexual intercourse, No. (%) | 125/139 (89.9) | 139/150 (92.7) | 149/158 (94.3) |

| Age of first intercourse, mean (SD), y | 12.9 (1.6) | 13.2 (1.6) | 13.0 (1.9) |

| Lifetime sexual partners, median (IQR) | 5 (3-10) | 6 (3-12) | 5 (3-10) |

| Frequency of intercourse, mean (SD) scoreb | 3.3 (1.5) | 3.4 (1.7) | 3.3 (1.7) |

| Frequency of condom use, mean (SD) scorec | 3.2 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.2) |

| Frequency of alcohol use with intercourse, mean (SD) scorec | 3.0 (1.1) | 2.97 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.3) |

| Frequency of cannabis use with intercourse, mean (SD) scorec | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.7 (1.0) |

| Lifetime self-reported STI, No. (%) yes | 26/139 (18.7) | 24/155 (15.5) | 29/158 (18.4) |

| Lifetime self-reported pregnancy, No. (%) yes | 39/141 (27.7) | 59/155 (38.1) | 53/160 (33.1) |

| Diagnosed STI at baseline, No. (%) yes | 13/142 (9.2) | 13/154 (8.4) | 18/161 (11.2) |

Abbreviations: SRRI, sexual risk reduction intervention; SRRI + ETOH, SRRI including alcohol content; SRRI + ETOH + THC, SRRI + ETOH plus cannabis content; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Because data were not obtained from all participants in each condition, denominators are provided where percentages are calculated.

Scale: 1 indicates a few times a year; 2, once a month; 3, once a week; 4, 2 to 3 times a week; 5, 4 to 5 times a week; and 6, almost every day.

Scale: 1 indicates never; 2, almost never; 3, sometimes; 4, almost always; and 5, always.

Consistent with epidemiologic data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showing that chlamydia is 3 to 4 times more prevalent than gonorrhea, chlamydia was more prevalent than gonorrhea in our sample. Of the 44 participants diagnosed with an STI at baseline, 35 (79.6%) were diagnosed with chlamydia, 6 (13.6%) with gonorrhea, and 3 (6.8%) with both. At follow-up, among the 31 participants diagnosed with an STI, 28 (90.3%) were diagnosed with chlamydia, 2 (6. 5%) with gonorrhea, and 1 (3.2%) with both.

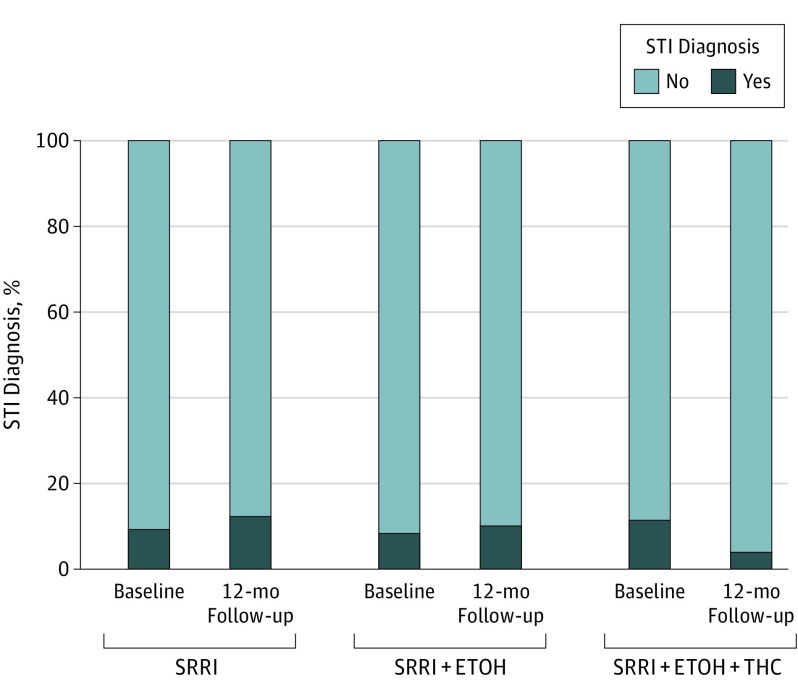

Proportions of positive STI diagnosis were 12.4% for the SRRI condition, 10.2% for the SRRI + ETOH condition, and 3.9% for the SRR + ETOH + THC condition at follow-up (Figure 2). Participants in the SRRI + ETOH + THC intervention had a lower incidence of STIs than those in the SRRI (odds ratio [OR], 0.29; 95% CI, 0.10-0.84; risk difference, 8.5%; 95% CI, 1.3%-15.6%) or SRRI + ETOH (OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.12-1.05; risk difference, 6.3%; 95% CI, 0.0003%-12.5%) interventions.

Figure 2. Percentage of Participants Diagnosed With Chlamydia trachomatis and/or Neisseria gonorrhoeae at Baseline and 12-Month Follow-up by Condition.

SRRI indicates sexual risk reduction intervention; SRRI + ETOH, SRRI including alcohol content; and SRRI+ + ETOH + THC, SRRI + ETOH plus cannabis content.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to verify the robustness of the reported findings. There was imbalance in Hispanic ethnicity across conditions. Although ethnicity was unrelated to STI diagnosis at 12 months and would not be expected to confound the relationship, the primary model was reestimated including Hispanic ethnicity as a model covariate. Results were equivalent to the primary modeling strategy (the OR comparing SRRI + ETOH + THC with SRRI changed from 0.29 to 0.30 [95% CI, 0.10-0.88]; the OR comparing SRRI + ETOH + THC with SRRI + ETOH changed from 0.36 to 0.38 [95% CI, 0.13-1.13]). A sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation that was conducted to supplement the reported complete case analysis also confirmed study conclusions (OR [95% CI]) comparing SRRI + ETOH + THC with SRRI and SRRI + ETOH + THC with SRRI + ETOH, respectively, were 0.35 (0.12-0.98) and 0.39 (0.14-1.06). Given the relatively few cases of gonorrhea in our sample, a final sensitivity analysis excluded those who were diagnosed with gonorrhea only, and conclusions were again unchanged.

Discussion

A MET-based intervention including theory-based sexual risk-reduction and alcohol- and cannabis-related content was more effective at reducing STI incidence among justice-involved adolescents than an intervention using a similar format that did not include substance use content.

Limitations

Our study had some limitations. This study did not include a no-treatment control condition, and findings may have somewhat limited generalizability to adolescents who are not regular substance users or adolescents in the juvenile justice system in other regions of the United States.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that intervention effects are not linked solely to mode of delivery; instead, substance-use content may play a role in reducing sexual risk among this vulnerable population. This cost-effective, easily disseminated intervention has real-world value for juvenile justice agencies.

Trial Protocol.

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics and Baseline Sexual Behavior and Substance Use Characteristics of Participants in the Analytic Sample of a Cluster Randomized Sexual Risk Reduction Intervention Trial in the Southwestern U.S. Conducted Between 2010 and 2014

eTable 2. Demographic Characteristics and Baseline Sexual Behavior and Substance Use Characteristics of Participants Retained in the Analytic Sample Versus Lost to Follow-up in a Cluster Randomized Sexual Risk Reduction Intervention Trial in the Southwestern U.S. Conducted Between 2010 and 2014

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fact Sheet:Reported STDs in the United States, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/STD-Trends-508.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2017.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2009. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats09/surv2009-complete.pdf. Published November 2010. Accessed June 1, 2017.

- 3.Montanaro E, Feldstein Ewing SW, Bryan AD. What works? an empirical perspective on how to retain youth in longitudinal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and substance risk reduction studies. Subst Abus. 2015;36(4):493-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ajzen I, Madden TJ. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22(5):453-474. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(86)90045-4 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheeran P, Maki A, Montanaro E, et al. . The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2016;35(11):1178-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldstein Ewing SW, Ryman SG, Gillman AS, Weiland BJ, Thayer RE, Bryan AD. Developmental cognitive neuroscience of adolescent sexual risk and alcohol use. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(suppl 1):S97-S108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldstein Ewing SW, Apodaca TR, Gaume J. Ambivalence: prerequisite for success in motivational interviewing with adolescents? Addiction. 2016;111(11):1900-1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cushing CC, Jensen CD, Miller MB, Leffingwell TR. Meta-analysis of motivational interviewing for adolescent health behavior: efficacy beyond substance use. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(6):1212-1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryan AD, Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR. HIV risk reduction among detained adolescents: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1180-e1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR, Levin M, Bryan AD. Randomized trial of group interventions to reduce HIV/STD risk and change theoretical mediators among detained adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(1):38-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carnevale JT, Kagan R, Murphy PJ, Esrick J. A practical framework for regulating for-profit recreational marijuana in US states: lessons from Colorado and Washington. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;42:71-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hopfer C. Implications of marijuana legalization for adolescent substance use. Subst Abus. 2014;35(4):331-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2015: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryan AD, Schmiege SJ, Magnan RE. Marijuana use and risky sexual behavior among high-risk adolescents: trajectories, risk factors, and event-level relationships. Dev Psychol. 2012;48(5):1429-1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritchwood TD, Ford H, DeCoster J, Sutton M, Lochman JE. Risky sexual behavior and substance use among adolescents: a meta-analysis. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;52:74-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donenberg GR, Emerson E, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Udell W. HIV-risk reduction with juvenile offenders on probation. J Child Fam Stud. 2015;24(6):1672-1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tolou-Shams M, Dauria E, Conrad SM, Kemp K, Johnson S, Brown LK. Outcomes of a family-based HIV prevention intervention for substance using juvenile offenders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;77:115-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010 [published correction appears in MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(1):18]. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR12):1-110.21160459 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callahan TJ, Montanaro E, Magnan RE, Bryan AD. Project MARS: design of a multi-behavior intervention trial for justice-involved youth. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3(1):122-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuckerman M. Zuckerman-Kuhlman personality questionnaire (ZKPQ): an alternative five-factorial model In: Perugini M, DeRaad B, eds. Big Five Assessment. Seattle, WA: Hogrefe & Huber; 2002:377. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams ML, Freeman RC, Bowen AM, et al. . A comparison of the reliability of self-reported drug use and sexual behaviors using computer-assisted versus face-to-face interviewing. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12(3):199-213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feldstein Ewing SW, Walters S, Baer J. Group Motivational Interviewing With Adolescents and Young Adults: Group Motivational Interviewing. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Amico EJ, Feldstein Ewing SW, Engle B, Osilla KC, Hunter S, Bryan A. Motivational Interviewing With Adolescents and Young Adults: Group Alcohol and Drug Treatment. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011:151-157. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmiege S, Bryan AD. Heterogeneity in the relationship of substance use to risky sexual behavior among justice-involved youth: a regression mixture modeling approach. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(4):821-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teplin LA, Elkington KS, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Mericle AA, Washburn JJ. Major mental disorders, substance use disorders, comorbidity, and HIV-AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(7):823-828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Callahan TJ, Caldwell Hooper AE, Thayer RE, Magnan RE, Bryan AD. Relationships between marijuana dependence and condom use intentions and behavior among justice-involved adolescents. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2715-2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually transmitted diseases: Table 1, reported cases and rates of reported cases per 100,000 population, United States, 1941-2016. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/CDC_2016_STDS_Report-for508WebSep21_2017_1644.pdf Udated September 26, 2017. Accessed November 25, 2017.

- 31.Dealy BC, Horn BP, Callahan TJ, Bryan AD. The economic impact of Project MARS (motivating adolescents to reduce sexual risk). Health Psychol. 2013;32(9):1003-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics and Baseline Sexual Behavior and Substance Use Characteristics of Participants in the Analytic Sample of a Cluster Randomized Sexual Risk Reduction Intervention Trial in the Southwestern U.S. Conducted Between 2010 and 2014

eTable 2. Demographic Characteristics and Baseline Sexual Behavior and Substance Use Characteristics of Participants Retained in the Analytic Sample Versus Lost to Follow-up in a Cluster Randomized Sexual Risk Reduction Intervention Trial in the Southwestern U.S. Conducted Between 2010 and 2014