Key Points

Question

In patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with fibrinolytic therapy, is ticagrelor noninferior to clopidogrel with respect to thrombolysis in myocardial infarction major bleeding at 30 days?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 3799 patients, delayed administration of ticagrelor after fibrinolytic therapy was noninferior to clopidogrel for thrombolysis in myocardial infarction major bleeding at 30 days. However, minor bleeding was increased with ticagrelor and there was no benefit on efficacy outcomes.

Meaning

Because most of the included patients were pretreated with clopidogrel, these findings reflect mostly the noninferiority of switching from clopidogrel to ticagrelor in patients already fully loaded with clopidogrel.

Abstract

Importance

The bleeding safety of ticagrelor in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with fibrinolytic therapy remains uncertain.

Objective

To evaluate the short-term safety of ticagrelor when compared with clopidogrel in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with fibrinolytic therapy.

Design, Setting and Participants

We conducted a multicenter, randomized, open-label with blinded end point adjudication trial that enrolled 3799 patients (younger than 75 years) with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction receiving fibrinolytic therapy in 152 sites from 10 countries from November 2015 through November 2017. The prespecified upper boundary for noninferiority for bleeding was an absolute margin of 1.0%.

Interventions

Patients were randomized to ticagrelor (180-mg loading dose, 90 mg twice daily thereafter) or clopidogrel (300-mg to 600-mg loading dose, 75 mg daily thereafter). Patients were randomized with a median of 11.4 hours after fibrinolysis, and 90% were pretreated with clopidogrel.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) major bleeding through 30 days.

Results

The mean (SD) age was 58.0 (9.5) years, 2928 of 3799 patients (77.1%) were men, and 2177 of 3799 patients (57.3%) were white. At 30 days, TIMI major bleeding had occurred in 14 of 1913 patients (0.73%) receiving ticagrelor and in 13 of 1886 patients (0.69%) receiving clopidogrel (absolute difference, 0.04%; 95% CI, −0.49% to 0.58%; P < .001 for noninferiority). Major bleeding defined by the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes criteria and by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium types 3 to 5 bleeding occurred in 23 patients (1.20%) in the ticagrelor group and in 26 patients (1.38%) in the clopidogrel group (absolute difference, −0.18%; 95% CI, −0.89% to 0.54; P = .001 for noninferiority). The rates of fatal (0.16% vs 0.11%; P = .67) and intracranial bleeding (0.42% vs 0.37%; P = .82) were similar between the ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups, respectively. Minor and minimal bleeding were more common with ticagrelor than with clopidogrel. The composite of death from vascular causes, myocardial infarction, or stroke occurred in 76 patients (4.0%) treated with ticagrelor and in 82 patients (4.3%) receiving clopidogrel (hazard ratio, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.67-1.25; P = .57).

Conclusions and Relevance

In patients younger than 75 years with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, delayed administration of ticagrelor after fibrinolytic therapy was noninferior to clopidogrel for TIMI major bleeding at 30 days.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02298088

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the short-term safety of ticagrelor when compared with clopidogrel in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with fibrinolytic therapy.

Introduction

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) represents the preferred reperfusion strategy for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).1,2 However, it is not possible for patients to be treated at hospitals with PCI capabilities in a timely manner as directed by clinical practice guidelines in many parts of the world.3,4 As a result, many patients with STEMI receive fibrinolytic therapy as the initial reperfusion strategy.1,2,3,4 Two large-scale randomized trials5,6 have established that dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel reduces major cardiovascular events in fibrinolytic-treated patients with STEMI.

Ticagrelor, a reversible and direct-acting oral antagonist of the adenosine diphosphate receptor P2Y12,7,8 provides faster, greater, and more consistent P2Y12 inhibition than clopidogrel. In the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) study,9 treatment with ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel significantly reduced the rate of death from vascular causes, MI, or stroke without an increase in the rate of overall major bleeding.

Despite these benefits, patients who received fibrinolytic therapy in the preceding 24 hours were excluded. Accordingly, to our knowledge, large-scale randomized trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of ticagrelor in this population have not been performed. The main concern regarding the use of ticagrelor in this scenario is related to the risk of major bleeding, especially intracranial or fatal bleeding. These patients with bleeding complications have greater rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and mortality. Thus, the Ticagrelor in Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Treated With Pharmacological Thrombolysis (TREAT) trial was conducted to evaluate the safety of ticagrelor in this clinical setting.

Methods

Study Design Oversight

The trial protocol is available in Supplement 1 and the statistical analysis plan is available in Supplement 2. Briefly, the TREAT trial10 was an academically led, phase 3, international, multicenter, randomized, and open-label study with blinded outcome assessment that involved 10 countries (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, New Zealand, Peru, Russia, and Ukraine). The steering committee, consisting exclusively of academic members, designed and oversaw the conduct of the trial. An independent data monitoring committee monitored the trial and had access to the unblinded data. Site management, data management, and analysis were performed by the Research Institute–Heart Hospital, São Paulo, Brazil. The study design was approved by the appropriate national and institutional regulatory authorities and ethics committees, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Patients

Patients were eligible for enrollment if they presented within 24 hours after the onset of symptoms, had evidence of acute ST-elevation on their qualifying electrocardiogram (at least 2 should be 1 mm in 2 contiguous peripheral or precordial leads in men and 1.5-mm elevation in V1-V3 in women and 1-mm in limb leads), were younger than 75 years, and received fibrinolytic therapy. Key exclusion criteria were any contraindication to the use of clopidogrel, use of oral anticoagulation therapy, an increased risk of bradycardia, and concomitant therapy with a strong cytochrome P-450 3A inhibitor or inducer. The complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in eMethods 1 of Supplement 3. Because patients who received fibrinolytic therapy in the previous 24 hours were excluded from the PLATO trial, we decided to include patients within 24 hours of symptom onset to fill the literature gap. Moreover, in an informal survey conducted with some potential sites before trial start, it was considered that establishing a very narrow window from fibrinolytic therapy to randomization would make recruitment very challenging. That approach would demand that the trial be conducted in small regional hospitals or mobile units, where the research infrastructure and expertise is very limited in most of the participating countries.

Randomization and Study Treatment

Patients were randomly assigned, in a 1 to 1 ratio, to receive ticagrelor with a loading dose of 180 mg or clopidogrel (with a loading dose of 300 to 600 mg) as early as possible after the index event and not more than 24 hours after the event. Randomization was performed in a concealed fashion with the use of an automated web-based system, in permuted blocks of 4, stratified according to site. Patients pretreated with clopidogrel before randomization were still eligible. If randomized to ticagrelor, the trial loading dose was recommended, and if randomized to clopidogrel, the patients could receive an additional 300 mg of clopidogrel at the discretion of the investigator and in accordance to local guidelines if undergoing PCI. The randomized maintenance therapy for ticagrelor was 90 mg twice daily and for clopidogrel was 75 mg once daily.

All patients received acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), 75 to 100 mg daily, during all the follow-up unless intolerant. For patients not previously receiving ASA, a loading dose of 162 mg to 325 mg was recommended. Investigators were encouraged to practice evidence-based medicine and follow appropriate guidelines1,2 in the other aspects of treating STEMI; decisions about the use of other treatments for acute MI and subsequent revascularization procedures were left to the discretion of the treating physicians.

Clinical Outcomes

The primary safety outcome was major bleeding, according to the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) definition. Secondary safety outcomes include major or minor bleeding according to the PLATO trial9,11 and the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC)12 definitions and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding or minor bleeding according to the TIMI definition.

Exploratory secondary efficacy outcomes included the composite outcome of death from vascular causes, MI, or stroke (similar to the PLATO primary outcome), and the same composite outcome with the addition of recurrent ischemia, transient ischemic attack, or other arterial thrombotic events. We evaluated individual components of the composite efficacy outcomes and all-cause mortality at 30 days.

The primary and secondary outcomes were adjudicated with the use of prespecified criteria by an independent clinical events committee whose members were unaware of the group assignments. Detailed definitions of outcomes are provided in eMethods 2 of Supplement 3.

Statistical Analysis

Concerns around major bleeding events were the main driver for the choice of the primary outcome of TREAT trial and for the noninferiority design. When TREAT was being designed, to our knowledge, there were no reported trials of ticagrelor in fibrinolytic-treated patients with STEMI that could inform major bleeding rates. Thus, we based our sample size on previous trials of ticagrelor in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI.13 In this regard, TIMI major bleeding rates at 30 days were projected to be around 1.2%. We considered an increase of bleeding of less than 1.0% to fulfill clinical criteria of noninferiority, which reflects what others have used as evidence of noninferiority regarding safety and efficacy outcomes, including major bleeding and mortality, in patients with acute coronary syndromes.14,15 We required a sample size of at least 1897 patients per group to provide greater than 90% statistical power, considering a noninferiority (absolute) margin of 1.0%, a 1-sided α of 2.5%, and assuming a 1 to 1 allocation ratio.

Continuous variables are reported as mean and standard deviation, or medians and interquartile range (IQR) as appropriate. Categorical variables are summarized as frequencies.

All patients who had been randomized to a treatment group were included in the intention-to-treat analyses. We also conducted sensitivity analyses in the per protocol population as prespecified in our statistical analysis plan (Supplement 2). Bleeding events were compared between groups based on the normal approximation to the binomial distribution. Efficacy outcomes were analyzed with the use of a Cox proportional hazards model. The point estimate and 2-sided 95% confidence intervals for the hazard ratio were calculated for each outcome. Prespecified safety and efficacy analyses were performed in subgroups according to age, sex, Killip risk score, diabetes mellitus, time from start of index event to randomization, aspirin, treatment with fibrin-specific or nonfibrin-specific fibrinolytics, and use of clopidogrel before randomization. The rates of bleeding and efficacy events are reported as percentages. All reported P values for noninferiority are 1-sided, and reported P values for superiority are 2-sided. All analyses were performed with the use of R (R Programming).16

Results

Study Patients and Study Drugs

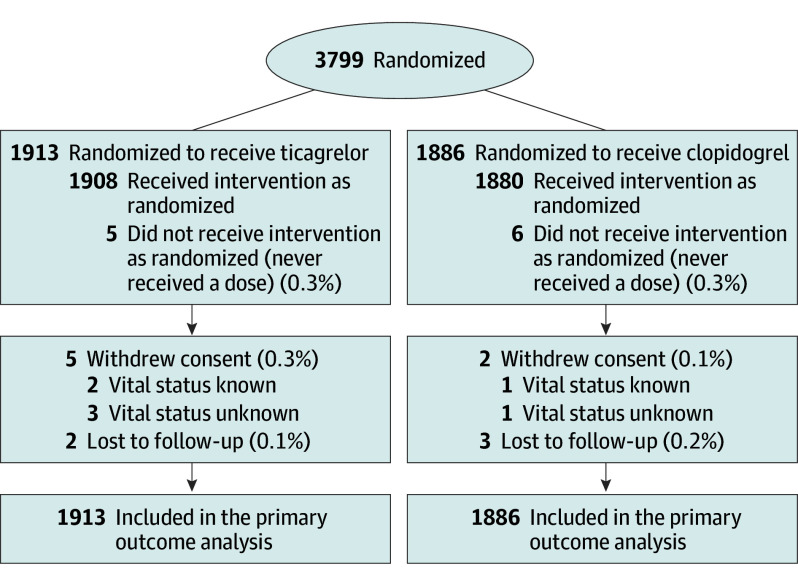

We recruited 3799 patients from 152 centers in 10 countries from November 2015 through November 2017. The follow-up period for the 30-day data ended in December 2017, when information on vital status was available for all patients except 8 (Figure 1). Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics. The mean (SD) age was 58.0 (9.5) years, 2928 of 3799 patients (77.1%) were men, 1759 of 3799 patients (46.3%) were current smokers, and 328 of 3799 patients (8.6%) had a history of MI. A total of 3795 of 3799 (99.9%) of the patients received fibrinolytic agent, of whom 2881 of 3799 (75.9%) received a fibrin-specific agent. The 2 treatment groups were well balanced as demonstrated by the baseline characteristics (Table 1) and the nonstudy medications and procedures (eTable 1 in Supplement 3). Both groups were randomized with a median of 2.6 hours (IQR, 1.5-4.3 hours) from chest pain to fibrinolytic therapy and had a median of 11.4 hours (IQR, 5.8-18.2 hours) after fibrinolytic therapy to randomization. In both groups, 3376 of 3774 patients (89.4%) received clopidogrel prior to randomization, usually at the 300-mg dose. A total of 3755 of 3799 patients (98.8%) received aspirin. The overall rate of adherence to the study drug at 30 days was 90.3%, as assessed by the site investigators.

Figure 1. Flow of Patients in TREAT Trial.

For most included patients, randomized treatment did not begin immediately but rather hours after initiation of fibrinolytic therapy. In this sense, patients randomized to ticagrelor received the first dose of ticagrelor several hours after initiation of fibrinolytic therapy (median, 11.4 hours), and 90% were pretreated with clopidogrel.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline.

| Characteristic | No./Total No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ticagrelor (n = 1913) | Clopidogrel (n = 1886) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 59 (51.6-65.2) | 58.8 (51.6-65.5) |

| Female | 433/1913 (22.6) | 438/1886 (23.2) |

| Median body weight, median (IQR), kg | 76.5 (68.0-88.0) | 77.0 (67.0-87.0) |

| Body weight <60 kg | 148/1911 (7.7) | 150/1885 (8.0) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 26.5 (24 29.8) | 26.5 (24.0-29.4) |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||

| White | 1100/1913 (57.5) | 1077/1886 (57.1) |

| Black | 73/1913 (3.8) | 61/1886 (3.2) |

| Asian | 631/1913 (33.0) | 639/1886 (33.9) |

| Other | 109/1913 (5.7) | 109/1886 (5.8) |

| Cardiovascular risk factor | ||

| Never smoker | 629/1913 (32.9) | 649/1886 (34.4) |

| Previous smoker | 403/1913 (21.1) | 359/1886 (19.0) |

| Habitual smoker | 881/1913 (46.1) | 878/1886 (46.6) |

| Hypertension | 1072/1913 (56.0) | 1071/1886 (56.8) |

| Dyslipidemia | 524/1913 (27.4) | 525/1886 (27.8) |

| Diabetes | 332/1913 (17.4) | 303/1886 (16.1) |

| Other medical history | ||

| MI | 178/1913 (9.3) | 150/1886 (8.0) |

| Stroke | 83/1913 (4.3) | 84/1886 (4.5) |

| PCI | 113/1913 (5.9) | 100/1886 (5.3) |

| CABG | 15/1913 (0.8) | 13/1886 (0.7) |

| Congestive heart failure | 38/1913 (2.0) | 37/1886 (2.0) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 17/1913 (0.9) | 16/1886 (0.8) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 21/1913 (1.1) | 24/1886 (1.3) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 50/1913 (2.6) | 45/1886 (2.4) |

| Asthma | 28/1913 (1.5) | 45/1886 (2.4) |

| Gout | 39/1913 (2.0) | 32/1886 (1.7) |

| ECG findings at study entry | ||

| STEMI (anterior alone) | 638/1905 (33.5) | 663/1878 (35.3) |

| STEMI (anterior and inferior) | 62/1905 (3.3) | 59/1878 (3.1) |

| STEMI (inferior alone) | 590/1905 (31.0) | 567/1878 (30.2) |

| STEMI (other) | 294/1905 (15.4) | 301/1878 (16.0) |

| Left bundle block | 20/1905 (1.0) | 25/1878 (1.4) |

| Positive troponin I test at study entry | 1542/1752 (88.0) | 1506/1728 (87.2) |

| Killip class (II, III, or IV) | 152/1913 (7.9) | 164/1886 (8.7) |

Abbreviatons: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; ECG, electrocardiographic; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Race/ethnicity was self-reported.

Bleeding

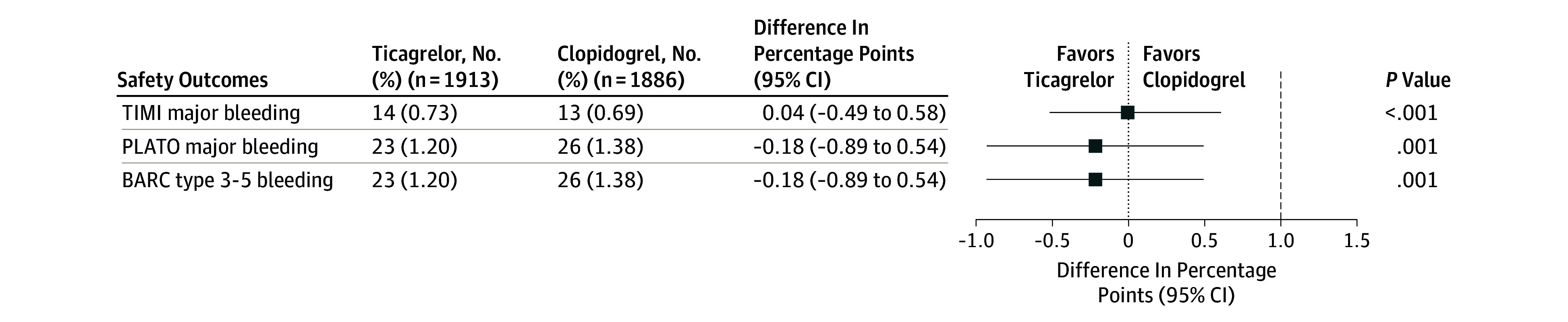

The primary outcome (TIMI major bleeding up to 30 days) occurred in 14 of 1913 patients (0.73%) in the ticagrelor group and 13 of 1886 patients (0.69%) in the clopidogrel group (absolute difference, 0.04%; 95% CI, −0.49% to 0.58%; P < .001 for noninferiority) (Figure 2; eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). Results were similar for the per protocol and other sensitivity analyses (eTable2 in Supplement 3). Major bleeding as assessed by the PLATO criteria and BARC types 3 to 5 bleeding occurred in 23 of 1913 patients (1.20%) in the ticagrelor group and in 26 of 1886 patients (1.38%) in the clopidogrel group (absolute difference, −0.18%; 95% CI, −0.89% to 0.54%; P = .001 for noninferiority) (Figure 2; eFigures 2 and 3 in Supplement 3).

Figure 2. Major Bleeding (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI], Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes [PLATO], and Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] Definitions) at 30 Days.

Difference (in percentage) presented as bilateral 95% confidence interval. 1% Absolute difference margin noninferiority test. Noninferiority test was done considering a 1-sided test.

The rates of fatal bleeding (0.16% vs 0.11%; P = .67) and intracranial bleeding (0.42% vs 0.37%; P = .82) were similar between the ticagrelor and the clopidogrel groups, respectively. Minor and minimal bleeding, as well as total bleeding, were more common with ticagrelor than with clopidogrel, irrespective of the classification used (Table 2).

Table 2. Other Bleeding.

| Safety Outcomes at 30 d | No. (%) | Absolute Difference, % (95% CI) | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ticagrelor (n = 1913) | Clopidogrel (n = 1886) | |||

| TIMI classification | ||||

| Minimal | 47 (2.46) | 30 (1.59) | 0.87 (−0.03 to 1.76) | .06 |

| Clinically significant bleeding | 61 (3.19) | 48 (2.55) | 0.64 (−0.42 to 1.70) | .23 |

| Requiring medical attention | 39 (2.04) | 24 (1.27) | 0.77 (−0.04 to 1.58) | .06 |

| Minor | 8 (0.42) | 11 (0.58) | −0.17 (−0.61 to 0.28) | .47 |

| Major non-CABG | 14 (0.73) | 11 (0.58) | 0.15 (−0.37 to 0.66) | .57 |

| Major CABG | 0 | 2 (0.11) | −0.11 (−0.25 to 0.04) | .15 |

| PLATO classification | ||||

| Minimal | 62 (3.24) | 38 (2.01) | 1.23 (0.21 to 2.24) | .02 |

| Minor | 23 (1.20) | 15 (0.80) | 0.41 (−0.22 to 1.04) | .21 |

| Other major | 8 (0.42) | 12 (0.64) | −0.22 (−0.68 to 0.24) | .35 |

| Major bleed, life-threatening | 15 (0.78) | 14 (0.74) | 0.04 (−0.51 to 0.60) | .88 |

| BARC classification | ||||

| Type 1 | 47 (2.46) | 30 (1.59) | 0.87 (−0.03 to 1.76) | .06 |

| Type 2 | 38 (1.99) | 23 (1.22) | 0.77 (−0.03 to 1.56) | .06 |

| Type 3a | 7 (0.37) | 12 (0.64) | −0.27 (−0.72 to 0.18) | .24 |

| Type 3b | 7 (0.37) | 6 (0.32) | 0.05 (−0.32 to 0.42) | .80 |

| Type 3c | 6 (0.31) | 5 (0.27) | 0.05 (−0.29 to 0.39) | .78 |

| Type 4 | 0 | 1 (0.05) | −0.05 (−0.16 to 0.05) | .31 |

| Type 5 | 4 (0.21) | 2 (0.11) | 0.10 (−0.15 to 0.35) | .42 |

| Any bleeding | 103 (5.38) | 72 (3.82) | 1.57 (0.24 to 2.90) | .02 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 8 (0.42) | 7 (0.37) | 0.05 (−0.35 to 0.45) | .82 |

| Fatal bleeding | 3 (0.16) | 2 (0.11) | 0.05 (−0.18 to 0.28) | .67 |

| Intracranial fatal bleeding | 2 (0.10) | 2 (0.11) | 0.00 (−0.21 to 0.20) | .99 |

Abbreviations: BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; PLATO, Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Two-sided P values are for superiority comparisons.

In patients who received study drugs within 4 hours after initiation of fibrinolytic therapy, the TIMI major bleeding events rates were 1.53% and 1.22% for the ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups, respectively (P = .73). Among these patients, there were also no statistically significant differences between ticagrelor and clopidogrel with respect to PLATO major bleeding and BARC types 3 to 5 bleeding rates (eFigure 4 in Supplement 3).

Efficacy

The exploratory secondary efficacy outcomes and interventions up to 30 days are shown in Table 3. The composite outcome of death from vascular causes, MI, or stroke occurred in 76 patients (4.0%) treated with ticagrelor and in 82 patients (4.3%) receiving clopidogrel (hazard ratio, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.67-1.25; P = .57). The rates of individual outcomes of MI, stroke, and other arterial thrombotic events were similar in the ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups.

Table 3. Efficacy Events Until 30 Days.

| Secondary Outcomes at 30 d | No. (%) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ticagrelor (n = 1913) | Clopidogrel (n = 1886) | |||

| Death from vascular causes, MI, or stroke | 76 (4.0) | 82 (4.3) | 0.91 (0.67-1.25) | .57 |

| Death from vascular causes, MI, or nonhemorrhagic strokeb | 70 (3.7) | 77 (4.1) | 0.90 (0.65-1.24) | .50 |

| Death from vascular causes, MI, stroke, severe recurrent ischemia, recurrent ischemia, TIA, or other arterial thrombotic event | 98 (5.1) | 95 (5.0) | 1.02 (0.77-1.35) | .90 |

| MI or deathb | 61 (3.2) | 67 (3.6) | 0.90 (0.63-1.27) | .54 |

| MI or strokeb | 38 (2.0) | 44 (2.3) | 0.85 (0.55-1.31) | .47 |

| Death (from vascular causes) | 47 (2.5) | 49 (2.6) | 0.95 (0.63-1.41) | .79 |

| MI | 20 (1.0) | 25 (1.3) | 0.79 (0.44-1.42) | .43 |

| Fatal | 8 (0.4) | 7 (0.4) | 1.13 (0.41-3.11) | .82 |

| Nonfatal | 12 (0.6) | 18 (1.0) | 0.66 (0.32-1.36) | .26 |

| Total stroke | 18 (0.9) | 20 (1.1) | 0.89 (0.47-1.68) | .71 |

| Hemorrhagic | 7 (0.4) | 7 (0.4) | NA | NA |

| Ischemic | 10 (0.5) | 13 (0.7) | NA | NA |

| Ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic transformation | 1 (0.1) | 0 | NA | NA |

| Uncertain | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| TIA | 0 | 1 (0.1) | NA | NA |

| Severe recurrent ischemia | 9 (0.5) | 6 (0.3) | 1.48 (0.53-4.17) | .45 |

| Other arterial thrombotic events | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) | 0.33 (0.03-3.16) | .34 |

| Death from any cause | 49 (2.6) | 49 (2.6) | 0.99 (0.66-1.47) | .95 |

Abbreviatons: MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not applicable; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

P values and hazard ratios were calculated by Cox regression analysis.

Post hoc analysis.

Other Adverse Events

Discontinuation of the study drug owing to serious adverse events was similar between ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups (0.40% vs 0.40%; P = .99). Dyspnea was more common in the ticagrelor group than in the clopidogrel group (in 265 of 1913 patients [13.9%] vs 144 of 1886 patients [7.6%], respectively) (eTable 3 in Supplement 3). Few patients discontinued the study drug because of dyspnea (19 of 1913 patients [1.0%] in the ticagrelor group and none in the clopidogrel group). The frequencies of serious adverse events were similar between groups.

Subgroup Analysis

The treatment effects of ticagrelor vs clopidogrel for the primary safety outcome and for the exploratory efficacy outcome were consistent among all subgroups (eTables 4 and 5 in Supplement 3).

Discussion

In this trial of patients younger than 75 years with STEMI who received fibrinolytic therapy as their initial reperfusion strategy,1,2 delayed administration of ticagrelor was noninferior to clopidogrel with respect to major bleeding (according to the TIMI, PLATO, and BARC classifications) at 30 days. Results were consistent between the intention-to-treat and per protocol analyses. Importantly, the rates of fatal and intracranial bleeding were also similar between the ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups. In contrast, the rates of minor, minimal, and total bleeding events were numerically higher with ticagrelor than with clopidogrel. Because most of the included patients were pretreated with clopidogrel, these findings reflect mostly the noninferiority of switching from clopidogrel to ticagrelor in patients already treated with clopidogrel.

Our findings are also consistent with previous smaller trials comparing ticagrelor and clopidogrel in patients with STEMI treated with fibrinolytics. A trial by Dehghani et al17 compared ticagrelor with clopidogrel in 144 patients undergoing early PCI post-reperfusion with tenectaplase. All patients received clopidogrel prerandomization, and the median time of thrombolytic administration to randomization (and initiation of ticagrelor vs clopidogrel) was about 6 hours. The BARC types 3 to 5 bleeding rates at 30 days were 1.3% in both the ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups at 30 days, which are similar to the rates observed in TREAT for the same outcome. The Sampling P2Y12 Receptor Inhibition With Prasugrel and Ticagrelor in Patients Submitted to Thrombolysis (SAMPA)18 trial compared ticagrelor and prasugrel in patients with STEMI post-fibrinolytic therapy. Similar to TREAT, all patients also received clopidogrel prerandomization, and the median time to randomization after thrombolytic therapy was 12.2 hours. No major bleeding events were observed within 30 days. Another small trial also found low bleeding rates in patients receiving ticagrelor after fibrinolytic therapy.19

Factors that could be related to the low major bleeding rates observed in our trial include the exclusion of patients older than 75 years, the predominantly male population, and the relative low risk of included patients. In addition, despite the fact that we used a very detailed and standardized adjudication process, lower transfusion rates in some participating countries could have decreased ascertainment of major bleeding events. Nevertheless, the major bleeding rates found in TREAT are similar to what was seen in the Clopidogrel and Metoprolol in Myocardial Infarction Trial (COMMIT)5 trial, in which rates of fatal, transfused, or intracranial bleeds together in fibrinolytic-treated patients who received clopidogrel were 0.65%.

Limitations

Comparisons of safety event rates between TREAT and other large-scale ticagrelor trials in patients with acute coronary syndromes are limited owing to differences in study designs, populations, and follow-up. Nevertheless, in the PLATO STEMI11 analysis, intracranial bleeding was very rare and not different between both groups (0.4% vs 0.2% in the ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups, respectively). This finding is similar to the rates observed in our trial. Given the observed low major bleeding rates, another important limitation of our trial is that one might consider our noninferiority margin of 1% to be quite wide and reflective of the modest sample size. This margin was chosen based on expert opinion and is similar to the margins used by previous acute coronary syndromes trials,14,15 although trials in populations similar to TREAT were not available at the time the protocol was designed. On the other hand, the upper boundaries of the confidence intervals for major bleeding according to different classifications were all lower than 0.6; thus, far from the 1% prespecified margin. Finally, as in previous ticagrelor trials, despite the fact that dyspnea was more common in patients receiving ticagrelor than clopidogrel, discontinuation owing to this adverse event was uncommon in the TREAT trial.

In our trial, rates of major cardiovascular events were similar between ticagrelor and clopidogrel at 30 days. Owing to the low number of events, our statistical power to assess superiority is limited; thus, these findings must be interpreted as exploratory. The lack of short-term differences between ticagrelor and clopidogrel is consistent with previous trials. In the PLATO STEMI11 analysis (n = 7544), the effects on major cardiovascular events appeared to accrue over time, and the event curves suggested that the bulk of the clinical benefit was obtained during long-term treatment. Additionally, our results might have been influenced, at least in part, by the stringent criteria that used by the clinical classification committee for outcomes, such as reinfarction, coupled with the challenge of adjudicating some of these outcomes in the setting of STEMI and rising biomarker levels.

The median time of thrombolytic administration to randomization, as is true for previous smaller studies, was about 11 hours, which is beyond the half-life of fibrin-specific fibrinolytics. Thus, it is likely that patients who had early bleeding events associated with fibrinolytic therapy were excluded. Nevertheless, in TREAT, we were still able to include patients within the first 4 hours of receiving fibrinolytic therapy. As expected, the TIMI major bleeding event rates at 30 days were higher (1.37% in both groups) in this subgroup compared with patients who were randomized later. Although our trial was not powered to determine noninferiority in specific subgroups, including patients who received ticagrelor soon after fibrinolytic therapy, major bleeding rates were numerically similar between groups irrespective of time from fibrinolytic therapy to randomization. Our trial does not address treatment of patients older than 75 years, who were excluded.

Most patients in our trial received clopidogrel prerandomization. In this regard, given that patients who received fibrinolytic therapy in the previous 24 hours were excluded from the PLATO trial and that STEMI guidelines2 recommend that ticagrelor should only be initiated after 48 hours after fibrinolysis, we believe that our trial adds new safety information to practicing physicians. Furthermore, approximately 50% of patients in the PLATO trial also received clopidogrel prior to randomization to either ticagrelor or clopidogrel and bleeding risk in these patients appeared to be comparable with those who had not received prior open-label clopidogrel. Based on our findings, patients with STEMI younger than 75 years who initially received clopidogrel can be safely switched to ticagrelor in the first 24 hours after fibrinolysis. Whether this strategy will result in fewer cardiovascular events in the long term remains to be determined. Our trial was an investigator-initiated trial with limited funding that did not allow a double-dummy design. We attempted to minimize the risk of bias associated with the open-label nature of the study by performing blinded outcome adjudication.

Conclusions

In patients younger than 75 years with STEMI, delayed administration of ticagrelor after fibrinolytic therapy was noninferior to clopidogrel for TIMI major bleeding at 30 days. However, minor bleeding was increased with ticagrelor, and there was no benefit on efficacy outcomes.

Trial Protocol.

Statistical Plan.

eMethods 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

eMethods 2. Outcome Definitions

eTable 1. Randomized Treatment, Other Treatment, and Procedures

eTable 2. Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 3. Reported Adverse Events

eTable 4. Effects of Ticagrelor vs Clopidogrel on TIMI Major Bleeding on Subgroups

eTable 5. Effects of Ticagrelor vs Clopidogrel on Death from Vascular Causes, MI, or Stroke on Subgroups

eFigure 1. Cumulative Kaplan-Meier Estimates of TIMI Major Bleeding Definition

eFigure 2. Cumulative Kaplan-Meier Estimates of PLATO Major Bleeding Definition

eFigure 3. Cumulative Kaplan-Meier Estimates of BARC Type 3-5 Bleeding Definition

eFigure 4. Major Bleeding (TIMI, PLATO and BARC Definitions) According to Time From Fibrinolytic Administration to Randomization

References

- 1.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. ; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines . 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127(4):e362-e425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vora AN, Holmes DN, Rokos I, et al. Fibrinolysis use among patients requiring interhospital transfer for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction care: a report from the US National Cardiovascular Data Registry. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):207-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandhi S, Zile B, Tan MK, et al. ; Canadian ACS Reflective Group . Increased uptake of guideline-recommended oral antiplatelet therapy: insights from the Canadian acute coronary syndrome reflective. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(12):1725-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen ZM, Jiang LX, Chen YP, et al. ; COMMIT (Clopidogrel and Metoprolol in Myocardial Infarction Trial) collaborative group . Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45,852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9497):1607-1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, et al. ; CLARITY-TIMI 28 Investigators . Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(12):1179-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Husted S, Emanuelsson H, Heptinstall S, Sandset PM, Wickens M, Peters G. Pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and safety of the oral reversible P2Y12 antagonist AZD6140 with aspirin in patients with atherosclerosis: a double-blind comparison to clopidogrel with aspirin. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(9):1038-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Husted S, van Giezen JJJ. Ticagrelor: the first reversibly binding oral P2Y12 receptor antagonist. Cardiovasc Ther. 2009;27(4):259-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. ; PLATO Investigators . Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1045-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berwanger O, Nicolau JC, Carvalho AC, et al. Ticagrelor versus Clopidogrel After Fibrinolytic Therapy in Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Rationale and Design of the TicagRElor in pAtients with ST elevation myocardial infarction treated with Thrombolysis (TREAT) trial. Am Heart J. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steg PG, James S, Harrington RA, et al. ; PLATO Study Group . Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes intended for reperfusion with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: A Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial subgroup analysis. Circulation. 2010;122(21):2131-2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123(23):2736-2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montalescot G, van ’t Hof AW, Lapostolle F, et al. ; ATLANTIC Investigators . Prehospital ticagrelor in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):1016-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van De Werf F, Adgey J, Ardissino D, et al. ; Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic (ASSENT-2) Investigators . Single-bolus tenecteplase compared with front-loaded alteplase in acute myocardial infarction: the ASSENT-2 double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354(9180):716-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone GW, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, et al. ; HORIZONS-AMI Trial Investigators . Bivalirudin during primary PCI in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(21):2218-2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.R-project.org/. Published 2017. Accessed January 1, 2018.

- 17.Dehghani P, Lavoie A, Lavi S, et al. Effects of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel on platelet function in fibrinolytic-treated STEMI patients undergoing early PCI. Am Heart J. 2017;192:105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guimarães LFC, Généreux P, Silveira D, et al. P2Y12receptor inhibition with prasugrel and ticagrelor in STEMI patients after fibrinolytic therapy: Analysis from the SAMPA randomized trial. Int J Cardiol. 2017;230:204-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexopoulos D, Perperis A, Koniari I, et al. Ticagrelor versus high dose clopidogrel in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients with high platelet reactivity post fibrinolysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;40(3):261-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

Statistical Plan.

eMethods 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

eMethods 2. Outcome Definitions

eTable 1. Randomized Treatment, Other Treatment, and Procedures

eTable 2. Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 3. Reported Adverse Events

eTable 4. Effects of Ticagrelor vs Clopidogrel on TIMI Major Bleeding on Subgroups

eTable 5. Effects of Ticagrelor vs Clopidogrel on Death from Vascular Causes, MI, or Stroke on Subgroups

eFigure 1. Cumulative Kaplan-Meier Estimates of TIMI Major Bleeding Definition

eFigure 2. Cumulative Kaplan-Meier Estimates of PLATO Major Bleeding Definition

eFigure 3. Cumulative Kaplan-Meier Estimates of BARC Type 3-5 Bleeding Definition

eFigure 4. Major Bleeding (TIMI, PLATO and BARC Definitions) According to Time From Fibrinolytic Administration to Randomization