Key Points

Question

How have mortality rates at baseline poor-performing hospitals for acute myocardial infarction and heart failure changed in response to policies of the past decade, including public reporting and value-based payment programs?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study, for acute myocardial infarction, 30-day mortality among baseline poor performers was higher at baseline but improved more over time compared with other hospitals (18.6% in 2009 to 14.6% in 2015 vs 15.7% to 14.0%). In contrast, for heart failure, baseline poor performers improved over time (13.5% to 13.0%), but mortality among all other heart failure hospitals increased (10.9% to 12.0%).

Meaning

Despite being subject to identical policy pressures, mortality trends for acute myocardial infarction and heart failure differed markedly between 2009 and 2015.

Abstract

Importance

Hospitals in the United States have been subject to mandatory public reporting of mortality rates for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and heart failure (HF) since 2007 and to value-based payment programs for these conditions since 2011. However, whether hospitals with initially poor baseline performance have improved relative to other hospitals under these programs, and whether patterns of improvement differ by condition, is unknown. Understanding trends within public reporting and value-based payment can inform future efforts in these areas.

Objective

To examine patterns in 30-day mortality from AMI and HF and determine whether they differ for baseline poor performers (worst quartile in 2009 and 2010 in public reporting, prior to value-based payment) compared with other hospitals.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cross-sectional study at US acute care hospitals from 2009 to 2015 that included 2751 and 3796 hospitals with publicly reported mortality data for AMI and HF, respectively.

Exposures

Public reporting and value-based purchasing.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Hospital-level risk-adjusted 30-day mortality rates.

Results

We identified 422 and 600 baseline poor-performing hospitals for AMI and HF, respectively. Baseline poor performers for AMI were more often public and for-profit and less often teaching hospitals. Baseline poor performers for HF were less often large hospitals. For AMI, 30-day mortality among baseline poor performers was higher at baseline but improved more over time compared with other hospitals (18.6% in 2009 to 14.6% in 2015; −0.74% per year; P < .001 vs 15.7% in 2009 to 14.0% in 2015; −0.26% per year; P < .001; P for interaction <.001). In contrast, for HF, baseline poor performers improved over time (13.5%-13.0%; −0.12% per year; P < .001), but mean mortality among all other HF hospitals increased during the study period (10.9%-12.0%; 0.17% per year; P < .001; P for interaction, <.001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Despite being subject to identical policy pressures, mortality trends for AMI and HF differed markedly between 2009 and 2015.

This cross-sectional study examines patterns in 30-day mortality from acute myocardial infarction and heart failure and determine whether they differ for baseline poor-performing hospitals compared with other hospitals in the United States.

Introduction

Hospitals in the United States have been subject to a number of major policy initiatives focused on acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and heart failure (HF) during the past decade. Quality of care for these conditions has been publicly reported since 2004, and 30-day mortality rates have been reported since 2007. Penalties for 30-day readmissions have been levied under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program since 2012, and penalties or bonuses for performance on a broad set of metrics have been paid under the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program since 2012. The intent of these programs was to improve quality and outcomes, particularly for hospitals with poor performance at baseline.

However, there has been substantial controversy regarding whether public reporting and value-based payment programs have collectively had positive or negative effects on the most important outcome for these cardiovascular conditions, 30-day mortality. Further, it is unknown whether these efforts have been associated with improvement among baseline poor performers, who were subject to the initial negative public reports and penalties and thus had the strongest incentive to improve. Such information is critical as policy makers and clinical leaders identify strategies to drive continued improvement in cardiovascular care.

Methods

We obtained publicly available risk-adjusted 30-day mortality rates for AMI and HF for US hospitals from 2009 to 2015 using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Hospital Compare. We defined baseline poor-performing hospitals as those in the worst quartile of mortality in both 2009 and 2010 for AMI or HF, respectively. We compared hospital characteristics between baseline poor performers and other hospitals using the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey and the Impact File. We created scatterplots with fitted trend lines of risk-adjusted mortality rates and calculated P values for trend using bivariate regression models. We then performed F tests to compare measures of variance during the study period and created logistic models to determine predictors for improvement using covariates of hospital size, profit status, region, rurality, membership in a system, presence of a medical or surgical intensive care unit (ICU), presence of a cardiac ICU, presence of a cardiac catheterization laboratory, and the proportion of Medicare and Medicaid patients split into quartiles. We included disproportionate share hospital index as a descriptive variable but did not include it as a covariate owing to collinearity with the proportion of Medicaid patients.

Finally, we performed several sensitivity analyses. We repeated analyses after defining baseline poor performers by the bottom decile of performance instead of bottom quartile. We also repeated analyses comparing the bottom quartile of hospitals with the top quartile of hospitals for both conditions. Finally, we examined trends for hospitals that performed poorly on both AMI and HF at baseline and compared dual poor performers with other hospitals.

All models were weighted by denominator values for the number of cases of AMI or HF, respectively, and standard errors were clustered at the hospital level. Given multiple comparisons, we considered 2-sided P values less than .01 statistically significant. This study was considered exempt by the University of Pennsylvania’s institutional review board. Patient consent was waived owing to the use of hospital-level data.

Results

We identified 2751 and 3796 hospitals with publicly reported mortality data for AMI and HF, respectively. Of these, 422 and 600 hospitals were identified as baseline poor performers (Table). Poor performers for AMI were more often public and for-profit and less often teaching hospitals. Poor performers for HF were less often large hospitals.

Table. Hospital Characteristics of Baseline Poor-Performing Hospitals vs All Other Hospitals.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Poor Performers in AMI (n = 422) | Other AMI Hospitals (n = 2329) | P Value | Baseline Poor Performers in HF (n = 600) | Other HF Hospitals (n = 3196) | P Value | |

| Hospital sizea | ||||||

| Small | 116 (27) | 539 (23) | .01 | 296 (49) | 1260 (39) | <.001 |

| Medium | 257 (61) | 1398 (60) | 268 (45) | 1528 (48) | ||

| Large | 49 (12) | 392 (17) | 36 (6) | 408 (13) | ||

| Profit status | ||||||

| Public | 87 (21) | 314 (13) | <.001 | 131 (22) | 636 (20) | .31 |

| Non-profit | 241 (57) | 1643 (71) | 385 (64) | 2045 (64) | ||

| For-profit | 94 (22) | 372 (16) | 84 (14) | 515 (16) | ||

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 50 (12) | 467 (21) | <.001 | 67 (11) | 480 (15) | .001 |

| South | 203 (48) | 879 (38) | 209 (35) | 1270 (40) | ||

| Midwest | 90 (21) | 598 (26) | 201 (34) | 921 (29) | ||

| West | 79 (19) | 385 (17) | 123 (21) | 525 (16) | ||

| Teaching | ||||||

| Yes | 99 (23) | 797 (34) | <.001 | 121 (20) | 847 (27) | .001 |

| Rural designation | ||||||

| Yes | 133 (32) | 509 (22) | <.001 | 278 (46) | 1100 (34) | <.001 |

| Member of system | ||||||

| Yes | 247 (59) | 1500 (64) | .02 | 326 (54) | 1890 (59) | .03 |

| MICU/SICU | ||||||

| Yes | 341 (94) | 1910 (95) | .67 | 435 (83) | 2262 (82) | .79 |

| Cardiac ICU | ||||||

| Yes | 163 (45) | 1028 (51) | .04 | 203 (39) | 1095 (40) | .60 |

| Cardiac catheterization laboratory | ||||||

| Yes | 234 (65) | 1398 (69) | .08 | 250 (48) | 1421 (52) | .08 |

| Prop Medicaid days, median (IQR) | 0.18 (0.13) | 0.17 (0.13) | .001 | 0.15 (0.12) | 0.16 (0.14) | .13 |

| Prop Medicare Days, median (IQR) | 0.52 (0.16) | 0.52 (0.17) | .43 | 0.54 (0.17) | 0.52 (0.19) | .001 |

| DSH quartileb | ||||||

| Quartile 1 | 47 (15) | 362 (20) | .006 | 66 (17) | 423 (20) | <.001 |

| Quartile 2 | 79 (25) | 542 (30) | 140 (37) | 549 (26) | ||

| Quartile 3 | 101 (32) | 517 (28) | 111 (29) | 587 (28) | ||

| Quartile 4 | 92 (29) | 402 (22) | 63 (17) | 515 (25) | ||

Abbreviations: AMI, acute myocardial infarction; DSH, disproportionate share hospital; HF, heart failure; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; MICU, medical intensive care unit; Prop, proportion; SICU, surgical intensive care unit.

Small, <100 beds; medium, 100-399 beds; large, ≥400 beds.

DSH indices are obtained from Impact File, which includes a smaller sample of hospitals.

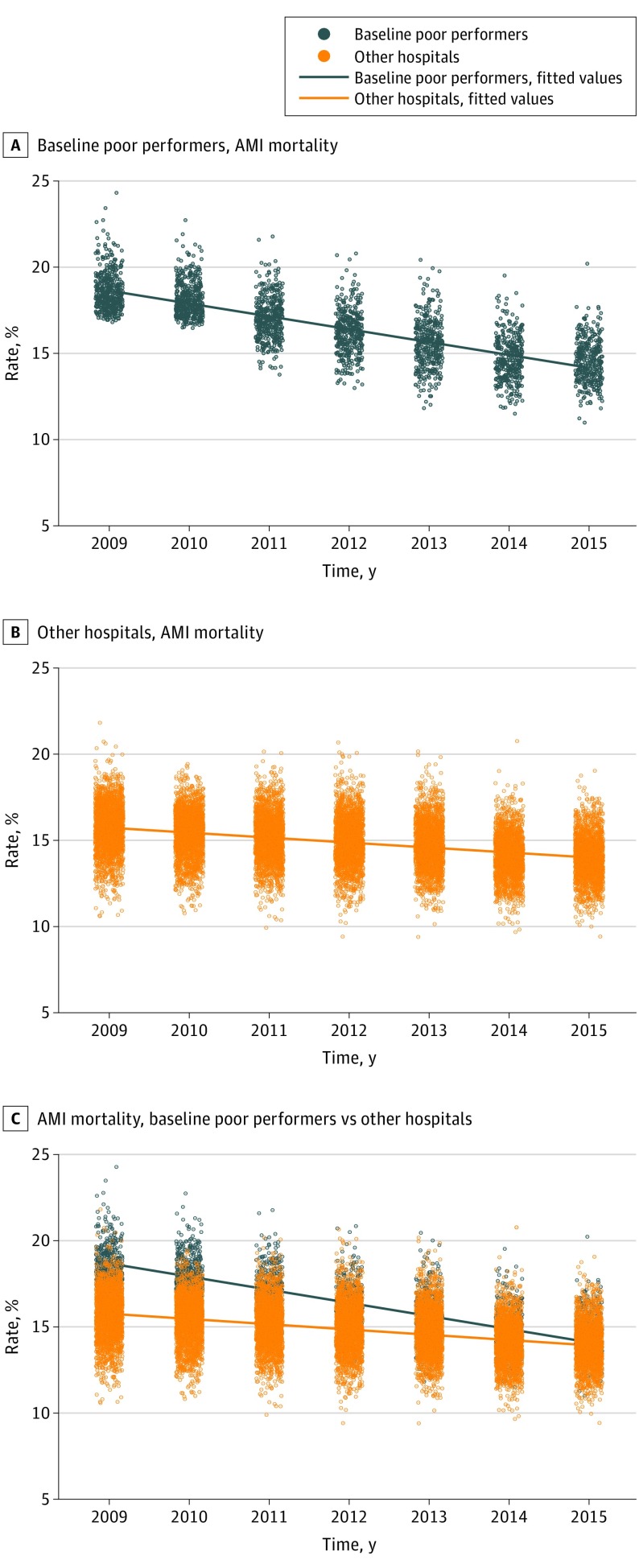

Mean AMI mortality among baseline poor performers was higher at baseline than all other hospitals at 18.6% but declined significantly to 14.6% in 2015 (−0.74% per year; P < .001; Figure 1A). Reductions in mortality among other hospitals were smaller during the same period but still significant (15.7% to 14.0%; −0.26% per year; P < .001; P for interaction <.001, Figure 1B), and consequently, the overall variance among the broad group of hospitals declined (SD, 1.69% to 1.25%; P < .001; Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) Mortality for Baseline Poor Performers and Other Hospitals.

Blue dots represent hospital performance on 30-day AMI mortality for baseline poor performers; orange dots represent hospital performance on 30-day AMI mortality for other hospitals; corresponding fitted lines are provided for trend.

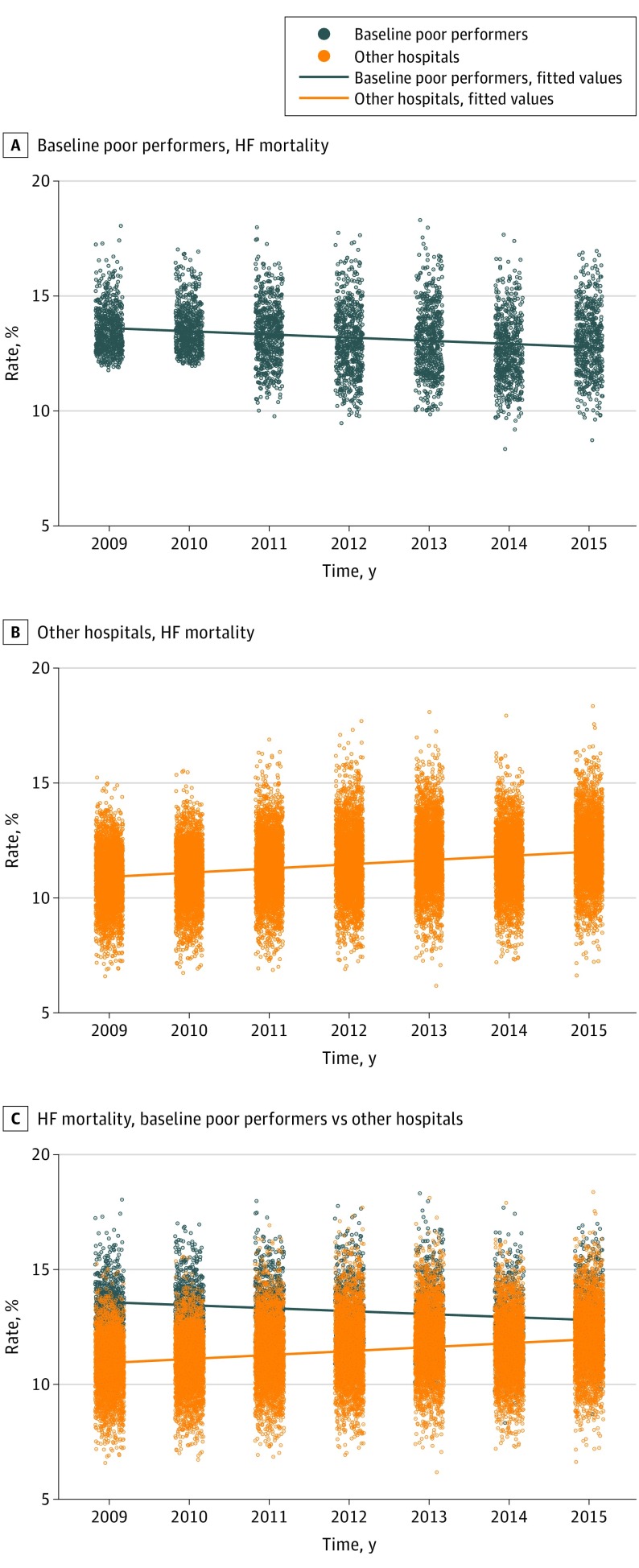

Patterns differed for HF. Mortality among baseline poor performers decreased from 13.5% to 13.0% (−0.12% per year; P < .001; Figure 2A), but during the same period, mortality among all other hospitals increased from 10.9% to 12.0% (0.17% per year; P < .001; P for interaction <.001; Figure 2B). Overall variance across the sample decreased minimally (SD, 1.52% to 1.47%; P < .001; Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Heart Failure (HF) Mortality for Baseline Poor Performers and Other Hospitals.

Blue dots represent hospital performance on 30-day HF mortality for baseline poor performers; orange dots represent hospital performance on 30-day HF mortality for other hospitals; corresponding fitted lines are provided for trend.

Of the characteristics listed in the Table, the presence of an ICU was associated with improvement among baseline poor performers for HF (odds ratio, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.08-2.00; P = .01, eTable in the Supplement), but there were no other measured characteristics significantly associated with improvement over time.

These results were consistent across sensitivity analyses. When we limited the sample to top and bottom quartiles of performers, we found similar results (eFigures 1-2 in the Supplement). Defining baseline poor performers by deciles instead of quartiles also yielded similar findings (eFigures 3-4 in the Supplement). Finally, when we examined hospitals that performed poorly on both AMI and HF at baseline, we found the same trends, with dual poor performers demonstrating more improvement in both domains, although more so in AMI than HF (eFigures 5-6 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Despite being subject to identical policy pressures, mortality trends for AMI and HF differed markedly between 2009 and 2015. Acute myocardial infarction mortality among both baseline poor performers and other hospitals fell significantly, whereas a small improvement among baseline poor performers in HF was offset by an increase in mortality in the remainder of hospitals.

It remains unclear why these trends should differ despite being the focus of the same policies. One possibility is that care improvements spurred by these policies have had a differential effect on the 2 conditions. For example, the growth of hospital efforts to adopt defined clinical pathways may have driven gains in AMI mortality more than HF mortality. Heart failure outcomes may be less sensitive to such pathway-based care, particularly for patients with preserved ejection fraction for whom mortality-reducing interventions remain elusive. Patients with HF also tend to be older and more medically complex, such that their mortality is less often cardiovascular in nature. As such, HF mortality may be more sensitive to the quality of outpatient longitudinal, multidisciplinary care rather than changes in inpatient treatment.

Another possibility is that trends in 30-day mortality during the past decade have not been the result of policy interventions aimed at inpatient care at all but are rather reflective of differential quality improvement in the outpatient setting. Because more HF care can be delivered to outpatients, it is feasible that patients admitted with HF have grown progressively sicker over the past decade. Alternatively, an increasing number of AMI survivors may go on to have severe forms of ischemic cardiomyopathy, potentially contributing to rising HF mortality.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. First, during the study period, there were several changes made to the methods used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to calculate 30-day mortality. However, we would expect all hospitals to have been affected equally by such policy changes, and our inclusion of all participating US hospitals lessens the likelihood of such selection effects. Second, we are unable to assess the contribution of regression of the mean to these overall trends.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found divergent national mortality trends for AMI and HF despite similar policy efforts directed at both conditions. There is much more to be learned about contributors to the patterns we have demonstrated, but such an understanding is critical to efforts to use policy to drive further improvements in outcomes and may warrant new focus from researchers and policy makers.

eTable. Predictors of Improvement

eFigure 1. Baseline Poor Performers vs Baseline Top Performers (Quartiles), Mortality for AMI

eFigure 2. Baseline Poor Performers vs Baseline Top Performers (Quartiles), Mortality for HF

eFigure 3. Baseline Poor Performers vs Baseline Top Performers (Deciles), Mortality for AMI

eFigure 4. Baseline Poor Performers vs Baseline Top Performers (Deciles), Mortality for HF

eFigure 5. Dual Poor Performers, AMI Mortality

eFigure 6. Dual Poor Performers, HF Mortality

References

- 1.US Department of Health & Human Services Hospital compare. https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html. Accessed January 21, 2018.

- 2.United States Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Readmissions Reduction Program. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Published 2017. Accessed January 21, 2018.

- 3.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Hospital value-based purchasing: the official website for the medicare hospital value-based purchasing program. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/hospital-value-based-purchasing/index.html. Published 2014. Accessed June 4, 2014.

- 4.Fonarow GC, Konstam MA, Yancy CW. The hospital readmission reduction program is associated with fewer readmissions, more deaths: time to reconsider. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(15):1931-1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dharmarajan K, Wang Y, Lin Z, et al. The relationship of changing hospital readmission rates and mortality rates after hospitalization. JAMA. 2017;318(3):270-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan AM, Dimick JB. Hospital quality and hospital value-based purchasing. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1501-1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta A, Allen LA, Bhatt DL, et al. Association of the hospital readmissions reduction program implementation with readmission and mortality outcomes in heart failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(1):44-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinberg BA, Zhao X, Heidenreich PA, et al. ; Get With the Guidelines Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators . Trends in patients hospitalized with heart failure and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence, therapies, and outcomes. Circulation. 2012;126(1):65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velagaleti RS, Pencina MJ, Murabito JM, et al. Long-term trends in the incidence of heart failure after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;118(20):2057-2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Predictors of Improvement

eFigure 1. Baseline Poor Performers vs Baseline Top Performers (Quartiles), Mortality for AMI

eFigure 2. Baseline Poor Performers vs Baseline Top Performers (Quartiles), Mortality for HF

eFigure 3. Baseline Poor Performers vs Baseline Top Performers (Deciles), Mortality for AMI

eFigure 4. Baseline Poor Performers vs Baseline Top Performers (Deciles), Mortality for HF

eFigure 5. Dual Poor Performers, AMI Mortality

eFigure 6. Dual Poor Performers, HF Mortality