This study measures and estimates the effect sizes of recurrent and nonrecurrent copy number variants on IQ.

Key Points

Question

Can we measure and estimate the effect sizes of recurrent and rare nonrecurrent pathogenic copy number variants on IQ?

Findings

The haploinsufficiency scores best explain the effect size of deletions on IQ measured in 1713 deletion carriers from 2 general population cohorts. IQ is affected by 2.74 points per deleted unit of the probability of being loss-of-function intolerant, and models estimate the effect size of deletions on IQ with a concordance of 0.75.

Meaning

Effect sizes on IQ of most deletions can be reliably estimated by models using haploinsufficiency scores, and the effect sizes of haploinsufficiency are broadly distributed across the genome.

Abstract

Importance;

Copy number variants (CNVs) classified as pathogenic are identified in 10% to 15% of patients referred for neurodevelopmental disorders. However, their effect sizes on cognitive traits measured as a continuum remain mostly unknown because most of them are too rare to be studied individually using association studies.

Objective

To measure and estimate the effect sizes of recurrent and nonrecurrent CNVs on IQ.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study identified all CNVs that were 50 kilobases (kb) or larger in 2 general population cohorts (the IMAGEN project and the Saguenay Youth Study) with measures of IQ. Linear regressions, including functional annotations of genes included in CNVs, were used to identify features to explain their association with IQ. Validation was performed using intraclass correlation that compared IQ estimated by the model with empirical data.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Performance IQ (PIQ), verbal IQ (VIQ), and frequency of de novo CNV events.

Results

The study included 2090 European adolescents from the IMAGEN study and 1983 children and parents from the Saguenay Youth Study. Of these, genotyping was performed on 1804 individuals from IMAGEN and 977 adolescents, 445 mothers, and 448 fathers (484 families) from the Saguenay Youth Study. We observed 4928 autosomal CNVs larger than 50 kb across both cohorts. For rare deletions, size, number of genes, and exons affect IQ, and each deleted gene is associated with a mean (SE) decrease in PIQ of 0.67 (0.19) points (P = 6 × 10−4); this is not so for rare duplications and frequent CNVs. Among 10 functional annotations, haploinsufficiency scores best explain the association of any deletions with PIQ with a mean (SE) decrease of 2.74 (0.68) points per unit of the probability of being loss-of-function intolerant (P = 8 × 10−5). Results are consistent across cohorts and unaffected by sensitivity analyses removing pathogenic CNVs. There is a 0.75 concordance (95% CI, 0.39-0.91) between the effect size on IQ estimated by our model and IQ loss calculated in previous studies of 15 recurrent CNVs. There is a close association between effect size on IQ and the frequency at which deletions occur de novo (odds ratio, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.84-0.87; P = 2.7 × 10−88). There is a 0.76 concordance (95% CI, 0.41-0.91) between de novo frequency estimated by the model and calculated using data from the DECIPHER database.

Conclusions and Relevance

Models trained on nonpathogenic deletions in the general population reliably estimate the effect size of pathogenic deletions and suggest omnigenic associations of haploinsufficiency with IQ. This represents a new framework to study variants too rare to perform individual association studies and can help estimate the cognitive effect of undocumented deletions in the neurodevelopmental clinic.

Introduction

Copy number variants (CNVs) contribute to a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) and psychiatric disorders, including intellectual disabilities (IDs), autism spectrum disorders, and schizophrenia.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 With the routine implementation of whole genome chromosomal microarrays in medical diagnostics, pathogenic CNVs (as defined by the American College of Medical Genetics10) are identified in 10% to 15% of children referred for NDDs.11 Copy number variants may arise recurrently by nonhomologous recombination in unrelated individuals. Several recurrent CNVs have been individually associated with IDs,7,8 autism spectrum disorders,1,2,3,12 and schizophrenia.5,6 Beyond association with a psychiatric diagnosis, little is known about the effect size of CNVs on cognitive traits. A study performed13 in the general population of Iceland found that 26 psychiatric CNVs reduce, in aggregate, IQ by 15 points or 1 SD. With the use of the cognitive tests available in the UK Biobank, 54 loci were associated with decreased scores, ranging from 0.1 to 0.5 SD.14

However, most pathogenic CNVs reported back to patients are undocumented because they are ultrarare or even private to the patient or family.11,15 They cannot be investigated using individual association studies. Their associations with cognition and mechanisms by which they lead to neurodevelopmental symptoms remain unknown. These nonrecurrent CNVs have been studied in aggregate by size categories in a general population sample of 6819 individuals from Estonia.16 In this cohort, rare, large, and intermediate (>250 kilobases [kb]) deletions and large, rare duplications (>1 megabase [Mb]) were found in 10% of the population. In aggregate, these CNVs were associated with IDs and adversely affected educational achievement; cognitive measures were unavailable.

The aim of this study was to calibrate and validate models to measure and estimate effect sizes of nonrecurrent pathogenic CNVs on general intelligence measured by IQ. To achieve this, we estimated effect sizes of rare recurrent and nonrecurrent CNVs on IQ using 2 general population cohorts. We then scored CNVs using 10 functional annotations to identify variables that contribute the most to variation in IQ. This model, which was subsequently validated, will help clinicians and researchers estimate the association of pathogenic CNVs with IQ.

Methods

Cohorts

General Population Cohorts

We used 2 cohorts recruited from the general population: IMAGEN,17 including 2090 adolescents from Europe, and the Saguenay Youth Study (SYS),18 including 1983 individuals (1032 children, 951 parents, 486 families) from Quebec, Canada. All children completed tests of verbal IQ (VIQ) and performance IQ (PIQ) using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition19 (subset) for IMAGEN and Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Third Edition20 for SYS. Distribution of IQ scores are available in eTable 1 in the Supplement. The IMAGEN project had obtained ethical approval by the local ethics committees and written informed consent from all participants and their legal guardians. For SYS, the institutional review boards of all participating institutions approved all studies reported herein. For SYS and IMAGEN, the parents and adolescents provided written informed consent and assent, respectively. All data were deidentified.

Clinical Cohorts

We used the chromosomal microarray database from the cytogenetic laboratory of the pediatric hospital of Center Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine (CHU-SJ; Montreal, Canada), including 16 586 individuals referred for NDDs, and the Simon simplex collection (SSC),12,21 including 2591 children with autism spectrum disorders and their family members.

Genotyping and CNV Detection

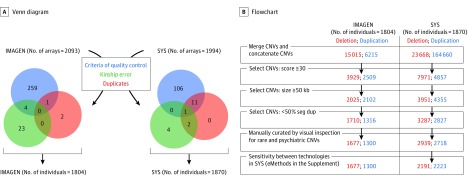

Genotyping technologies are detailed in the eMethods in the Supplement. A total of 1804 individuals from IMAGEN and 977 adolescents, 445 mothers, and 448 fathers (484 families) from SYS (Figure 1A) met stringent quality control criteria (call rate ≥99%, log R ratio SD <0.35, B allele frequency SD <0.08, and wave factor <0.05). We computed relatedness separately in IMAGEN and SYS based on the identity by state using PLINK.22 The CNV detections from PennCNV23 and QuantiSNP24 were combined to minimize the number of potential false discoveries. We used standard filtering strategies detailed in the eMethods in the Supplement.

Figure 1. Venn Diagram and Flowchart for Quality Control of Arrays and Copy Number Variants (CNVs).

A, Venn diagram representing different steps of microarray selection by quality control and verification of genetic information. The blue circle represents an array without good quality control. The green circle represents individuals having discordance between pedigree information and array (sex and relationship). The red circle represents duplicated microarrays. B, Flowchart representing the steps of CNVs selection after that microarray with good quality was selected. kb indicates kilobase; seg dup, segmental duplication; and SYS, Saguenay Youth Study.

Annotation of CNVs

We annotated CNVs for size and number of genes using RefSeq genes (https://genome.ucsc.edu/), and genes were annotated using the probability of being loss-of-function intolerant (pLI),25 the residual variation intolerance score,26 the score rate for intolerance for deletions and duplications,27 the number of protein-protein interactions,28 and the differential stability score29 of regional patterns of gene expression in the brain. These 5 scores were transformed, and the score associated with a CNV is the sum of scores of genes with all isoforms fully contained in the CNV (complete genes) (eMethods in the Supplement). The CNVs were also annotated with 2 lists of genes, including postsynaptic density of the human cortex,30 genes regulated by the Fragile-X mental retardation protein,31 and the number of expression quantitative trait loci regulating genes expressed in the brain32 (eMethods and eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

Only autosomal CNVs were analyzed, and 3 outliers were excluded (eMethods in the Supplement). P < .05 indicates statistical significance, and all tests were 2-sided.

Quantifying the Effect Size and Numbers of Genes and Exons of Autosomal CNVs on IQ

We performed 3 multiple linear regressions to quantify the effect size of CNVs (model 1), number of genes (model 2), and number of exons (model 3) on PIQ and VIQ. For each model, the variable of interest was measured in 4 categories of CNVs according to frequency (rare or common) and type (deletion or duplication). Models 1 through 3 included adjustment for ancestry, sex, age, microarray technology, and intrafamilial relatedness (eMethods and eFigure 1 in Supplement).

Characteristics of Autosomal Deletion Contents That Affect IQ

We performed a stepwise variables selection procedure based on the Bayesian information criterion33 to investigate 10 variables that would best explain the association of deletions with PIQ and VIQ (eMethods in the Supplement). The best model is denoted as model 4 in the remainder of this article. Sensitivity analyses were performed for models 1 through 4 (eMethods in the Supplement).

We then examined whether model 4 could predict the association of IQ with 15 known recurrent CNVs by calculating the concordance between model prediction and empirically measured loss of IQ obtained from previous publications (eMethods, eFigures 2 and 3, and eTable 3 in the Supplement). The concordance was computed using the intraclass coefficient correlation (3,1) (ICC3,1).34

Association Between Effect Size of CNVs on IQ and De Novo Frequency

Using data on inheritance from the CHU-SJ and SSC cohorts, we performed a logistic regression model (model 5) to establish the association between the probability at which CNVs occur de novo and their association with IQ predicted by model 4. We computed the ICC3,1 to evaluate the concordance between the probability for a CNV to be de novo predicted by model 5 and de novo frequency for the same 15 recurrent CNVs using data from the DECIPHER database (http://decipher.sanger.ac.uk) (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Results

Quantifying the Effect Size of CNVs, Number of Genes, and Number of Exons on IQ

We observed 4928 autosomal CNVs larger than 50 kb across both cohorts (Figure 1B and Table 1). Rare CNVs of 250 kb or larger (n = 308) are mostly nonrecurrent (92.8%), and their frequencies, similar across both cohorts, are identical to a previously published study16 (eResults, eFigure 4, and eTables 4-6 in the Supplement). We examined variables recurrently associated with NDDs and psychiatric disorders,7,8,16 namely, CNV size (model 1), number of genes (model 2), and number of exons (model 3), and estimated their association with IQ for 4 CNV categories, namely, common and rare deletions and duplications. In all 3 models, only rare deletions had significant effects on IQ. The effect of size (model 1) can be illustrated by a decrease of PIQ (mean [SE], 5.7 [2.0] points; P = 6 × 10−4) and VIQ (mean [SE], 3.6 [2.0] points; P = .03) for each deleted Mb (Table 2). These results are concordant with comparisons between carriers and noncarriers of rare CNVs stratified by size (eTable 7 in the Supplement). In model 2, each gene deleted by a rare CNV decreases PIQ by a mean (SE) of 0.67 (0.19) points (P = 6 × 10−4) and VIQ by 0.72 (0.19) points (P = 2 × 10−4). In model 3, each exon deleted by a rare CNV decreases PIQ by a mean (SE) of 0.07 (0.02) points (P = 2 × 10−5) and VIQ by 0.06 (0.02) points. For models 1 through 3, effects are similar in both cohorts separately. We found no measurable associations of common deletions or duplications with IQ (Table 2). The distributions of Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion, obtained by fitting the models 1 through 3 on 1000 bootstrap samples of the pooled data set each, show that gene and exon contents provide a better fit than size (eTable 8 in the Supplement). Applying models 1 through 3 on individuals with European ancestry shows similar results (eTable 9 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Description of IMAGEN and Saguenay Youth Study Cohortsa.

| Variable | IMAGEN (610Kq and 660Wq) | Saguenay Youth Study (Children) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 610Kq Illumina | Human Omni Express Version 12 | ||

| No. of samples (with PIQ or VIQ) | 1744b | 559 | 408 |

| Chromosomes 1-22 | |||

| No. of deletions | |||

| Total | 1584 | 609 | 483 |

| By sample | 0.9 (0.9) | 1.1 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.2) |

| No. of duplications | |||

| Total | 1179 | 608 | 465 |

| By sample | 0.7 (0.8) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.1) |

| No. of exonic deletionsc | |||

| Total | 308 | 185 | 115 |

| By sample | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.5) |

| No. of exonic duplicationsc | |||

| Total | 519 | 264 | 219 |

| By sample | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.8) |

| Chromosome X | |||

| No. of deletions | |||

| Total | 34 | 10 | 6 |

| By sample | 0.02 (0.1) | 0.02 (0.1) | 0.01 (0.1) |

| No. of duplications | |||

| Total | 82 | 53 | 38 |

| By sample | 0.05 (0.2) | 0.09 (0.3) | 0.09 (0.3) |

| No. of exonic deletionsc | |||

| Total | 9 | 2 | 0 |

| By sample | 0.01 (0.07) | 0.004 (0.06) | 0 (0) |

| No. of exonic duplicationsc | |||

| Total | 52 | 16 | 7 |

| By sample | 0.03 (0.2) | 0.03 (0.2) | 0.02 (0.1) |

| Age, mod | 173.4 (4.4) | 173.4 (22.7) | 178.9 (21.1) |

| Male, No. (%) | 853 (48.9) | 261 (46.7) | 201 (49.3) |

| PIQ | 106.6 (14.8) | 105.4 (13.2) | 103.2 (12.9) |

| VIQ | 110.0 (15.8) | 103.7 (12.5) | 104.4 (12.3) |

Abbreviations: CNV, copy number variant; PIQ, performance intelligence quotient; VIQ, verbal intelligence quotient.

Data are presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

One sample has PIQ but not VIQ.

The term exonic refers to a CNV that includes at least 1 gene (only complete genes are considered).

Age after imputation by mean of the cohort for the 376 samples with missing data in the IMAGEN cohort. The PIQ and VIQ means differ between the IMAGEN and SYS cohorts (2-tailed, unpaired t test, P < 2 × 10−4).

Table 2. CNV Size and Numbers of Coding Protein Genes and Exons, Summed Across All CNVs Carried by the Same Individuala.

| CNV Category | CNV Size, Mb | No. of Genes in CNVs | No. of Exons of CNVs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Carriers | PIQ Regression Coefficient, Mean (SE) [P Value] | VIQ Regression Coefficient, Mean (SE) [P Value] | No. of Carriers | PIQ Regression Coefficient, Mean (SE) [P Value] | VIQ Regression Coefficient, Mean (SE) [P Value] | No. of Carriers | PIQ Regression Coefficient, Mean (SE) [P Value] | VIQ Regression Coefficient, Mean (SE) [P Value] | |

| IMAGEN (n = 1744) | |||||||||

| Rare deletions | 391 | −4.41 (2.01) [.02] | −0.84 (2.14) [.69] | 69 | −0.71 (0.34) [.03] | −0.7 (0.37) [.05] | 162 | −0.06 (0.03) [.02] | −0.03 (0.03) [.23] |

| Rare duplications | 357 | 1.53 (1.61) [.34] | 1.81 (1.71) [.29] | 142 | 0.21 (0.2) [.29] | 0.03 (0.21) [.90] | 238 | 0.03 (0.02) [.13] | 0.02 (0.02) [.45] |

| Common deletions | 845 | −0.51 (3.91) [.89] | 1.18 (4.16) [.77] | 222 | −0.62 (0.28) [.02] | −0.4 (0.3) [.18] | 275 | −0.05 (0.02) [.02] | −0.03 (0.03) [.30] |

| Common duplications | 639 | 0.58 (1.47) [.69] | −0.28 (1.57) [.85] | 344 | 0.24 (0.16) [.13] | −0.19 (0.17) [.27] | 475 | 0.02 (0.02) [.19] | −0.02 (0.02) [.16] |

| SYS (n = 967) | |||||||||

| Rare deletions | 118 | −8.7 (2.9) [.002] | −9.29 (2.72) [7 × 10−4] | 25 | −0.62 (0.22) [.005] | −0.75 (0.21) [5 × 10−4] | 55 | −0.07 (0.02) [5 × 10−4] | −0.08 (0.02) [1 × 10−4] |

| Rare duplications | 140 | −0.83 (1.24) [.50] | 0.51 (1.16) [.66] | 67 | −0.38 (0.18) [.03] | −0.1 (0.17) [.55] | 105 | −0.04 (0.02) [.006] | −0.01 (0.02) [.48] |

| Common deletions | 622 | 0.52 (2.43) [.83] | −0.84 (2.28) [.71] | 252 | 0.08 (0.24) [.75] | 0.17 (0.22) [.45] | 352 | 0.05 (0.06) [.35] | 0.06 (0.05) [.29] |

| Common duplications | 577 | 2.18 (1.69) [.19] | 0.36 (1.59) [.81] | 313 | −0.02 (0.19) [.91] | −0.13 (0.18) [.47] | 414 | 0.03 (0.02) [.15] | −0.01 (0.02) [.62] |

| Both (n = 2711) | |||||||||

| Rare deletions | 509 | −5.7 (1.64) [6 × 10−4] | −3.63 (1.68) [.03] | 94 | −0.67 (0.19) [6 × 10−4] | −0.72 (0.19) [2 × 10−4] | 217 | −0.07 (0.02) [2 × 10−5] | −0.06 (0.02) [4 × 10−4] |

| Rare duplications | 497 | 0.06 (1) [.95] | 0.95 (1.01) [.34] | 209 | −0.1 (0.13) [.47] | −0.01 (0.14) [.93] | 343 | −0.01 (0.01) [.30] | 0 (0.01) [.77] |

| Common deletions | 1467 | 0.15 (2.12) [.94] | −0.27 (2.13) [.89] | 474 | −0.24 (0.19) [.19] | −0.07 (0.19) [.69] | 627 | −0.04 (0.02) [.04] | −0.02 (0.02) [.36] |

| Common duplications | 1216 | 1.04 (1.12) [.35] | −0.14 (1.15) [.90] | 657 | 0.16 (0.12) [.18] | −0.16 (0.13) [.21] | 889 | 0.02 (0.01) [.04] | −0.02 (0.01) [.18] |

Abbreviations: CNV, copy number variant; Mb, megabase; PIQ, performance IQ; SYS, Saguenay Youth Study; and VIQ, verbal IQ.

We used multiple regression analysis to study the estimated associations with PIQ and VIQ of the sum of autosomic CNV (≥50 kilobases [kb]) size and the sum of coding protein gene (for all isoforms) and exons for IMAGEN and SYS. Covariates included the 6 first principal components of genetic distance, sex, age, array technology, and familial relatedness. There was no interaction between sex and CNV categories, and this interaction term was subsequently removed. For size, the estimate of −5.7 translates into a loss of 5 points of PIQ per metabase of material included in rare deletions. For the number of genes, the estimate of −0.67 translates into a loss of 0.67 points of IQ per gene included in a rare deletion (Bonferroni correction = 0.008). Results are unchanged if only individuals with more than 80% of European ancestry are included (eTable 11 in the Supplement).

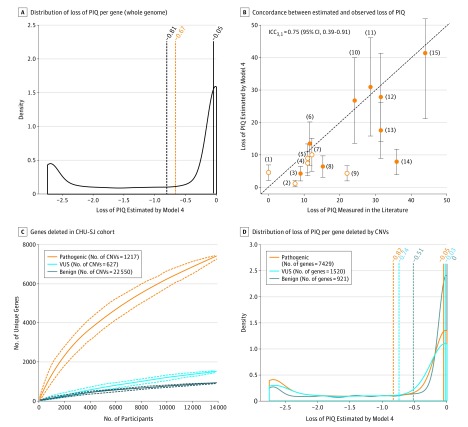

Characteristics Underlying the Associations of Deletions With IQ

To understand factors that potentially drive the associations of deletions with IQ, we investigated 10 functional annotations in the subset of 1713 individuals carrying at least 1 autosomal deletion in the pooled data set. The stepwise variable selection procedure converges on model 4, including pLI alone (PIQ: effect = −2.69, bias corrected effect = −2.74, SE = 0.68, P = 8 × 10−5; VIQ: effect = −2.41; bias corrected effect = −2.52; SE = 0.71; P = 7 × 10−4). The associations of pLI estimated in IMAGEN and SYS separately are the same, and no differences are observed between the association with PIQ and VIQ (eTable 10 in the Supplement). In the bootstrap procedure, pLI is the most frequently selected covariate for PIQ (37.8%) and the second most frequently selected covariate for VIQ (23.5%) behind the residual variation intolerance score (28.1%) and is always preferred to size or number of genes. Model 4 relies on pLI score, and the distribution of associations with PIQ of 17 102 individual genes shows that 33% of coding genes are predicted to affect PIQ by 1 point or more and 23% by 2 points or more. More than 968 genes (6%) have a maximum pLI of 1, with a corresponding effect size of −2.7 for PIQ and −2.5 for VIQ (Figure 2A and eFigure 5A in the Supplement), demonstrating that the model cannot estimate the association of 93 causal genes for IDs with very large or extreme associations with IQ35 (eTable 3 and eFigure 6 in the Supplement). The variable selection procedure, performed after a principal component analysis does not provide a better fit than model 4 (eMethods, eResults, eFigure 7, eTables 12 and 13 in the Supplement). Of note, there is no interaction between sex and any of the variables tested in models 1 through 4.

Figure 2. Predicted Loss of Performance IQ (PIQ) for Recurrent Copy Number Variants (CNVs) and Nonrecurrent CNVs Observed in the Clinic.

A, Distribution of the loss of PIQ per gene estimated by the model 4 for all RefSeq genes (N = 17 102). The black solid vertical line is the median, the dashed black vertical line is the mean, and the dashed orange vertical line is the mean individual effect of genes included in rare deletions (model 2). Of note, 36% of genes have an associated estimated loss of PIQ less than −0.67, 33% (n = 5597) are predicted to affect IQ greater than or equal to 1 point, 23% (n = 3949) by greater than or equal to 2 points, and 6% (n = 968) have maximum effect size. B, Concordance between loss of PIQ estimated by model 4 (y-axis) and loss of PIQ measured by previously published studies (x-axis) for 15 recurrent CNVs. Each point corresponds to a known recurrent CNV: (1) 17p12_(HNPP), (2) 16p12.1, (3) 15q11.2, (4) 16p13.11, (5) 1q21.1 TAR, (6) 17q12, (7) 16p11.2 Distal (SH2B1), (8) 1q21.1 Distal (Class I), (9) 15q13.3 (BP4-BP5), (10) 16p11.2 proximal (BP4-BP5), (11) 22q11.2, (12) 7q11.23 (William-Beuren), (13) 3q29 (DLG1), (14) 8p23.1, and (15) 17p11.2 (Smith-Magenis). The diagonal dashed line represents exact concordance. When loss of IQ was not directly measured in a previous study, we derived the loss of IQ from the published OR measuring the enrichment of a CNV in the neurodevelopmental clinic (open circles). Of note, the PIQ loss estimated by the model is 4.4 points for the 17q21.31 deletion, including KANSL1 a causal gene for intellectual disabilities. This is discordant with the estimated decrease of 36.3 points based on empirical data from the literature. Including this CNV, the concordance is 0.62 (95% CI, 0.20-0.85). C, Coverage of genes by the Center Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine (CHU-SJ) cohort according to significance level of CNVs. The y-axis represents the number of unique genes observed in the cohort, and the x-axis represents the number of individuals seen in the cohort. Coverage was obtained using 1000 iterations (bootstrap procedure on the order of individuals’ inclusion). D, Density of loss of PIQ estimated by the model 4 for genes included in CNVs from CHU-SJ for the different clinical significance category of CNVs. Solid lines correspond to medians, and the dashed lines correspond to means. ICC3,1 indicates intraclass correlation coefficient (1, 3); VUS, variant of unknown significance.

Sensitivity Analyses

We examined whether a subgroup of CNVs biased or overly influenced the results. Sensitivity analyses show that effect sizes of rare deletions and pLI on IQ are unchanged even after removing carriers with CNVs of 1 Mb or greater as well as recurrent CNVs previously associated with psychiatric NDDs. Transformed variables did not improve any of the models (eTables 14-16 in the Supplement). Additional sensitivity test results are detailed in eResults in the Supplement.

Model Validation

We compared IQ loss predicted by the model to IQ loss empirically measured in previous studies20,21 of 15 known recurrent CNVs without causal genes for IDs (eTable 3 and eFigure 6 in the Supplement). The concordance is 0.75 for PIQ (95% CI, 0.39-0.91; P = 5 × 10−4) and 0.72 for VIQ (95% CI, 0.35-0.90, P = 8 × 10−4) (Figure 2B and eFigure 5B in the Supplement). Widths of CIs are correlated with the effect size of the CNV, reflecting that CNVs with high pLI are rarely observed and are different from the distribution of CNVs observed in our general population cohorts. Of note, these results are similar whether we include or exclude, from the training data set, the 3 recurrent CNVs observed in 6 individuals in the pooled cohort (16p11.2 proximal BP4-BP5: 1 adolescent from IMAGEN; 16p12.1: 1 adolescent from IMAGEN and 2 sisters from SYS; 16p13.11: 2 adolescents from IMAGEN).

Implication for Medical Genetics

The widespread but small effect size of haploinsufficiency implies that pathogenic deletions could be found throughout the genome if the aggregate haploinsufficiency score is high enough to affect IQ. This finding is consistent with the fact that more than one-third (7429) of the coding genome is deleted by 1217 pathogenic autosomal deletions reported back to patients by the CHU-SJ (Figure 2C). Of note, genes included in pathogenic variants (n = 6799) or variants of unknown significance deletions (n = 1396) have a higher pLI than those included in benign deletions (n = 928) (Wilcoxon P = 4.8 × 10−14 for genes included in pathogenic versus benign deletions and Wilcoxon P = 9.7 × 10−6 for genes included in variant of unknown significance vs benign deletions) (Figure 2D and eFigure 5C in the Supplement).

As an illustration, we estimated the association with IQ of the aforementioned 1217 pathogenic deletions: the top quartile (25% of CNVs) is estimated to decrease IQ by more than 28 points, whereas the 2 middle quartiles decrease IQ between 28 and 4 points (eTable 17 in the Supplement). Of note, estimates for the lower quartile are smaller than a 4-point decrease in IQ, but most of the latter CNVs cannot be estimated properly because they disrupt a causal gene with large effects.

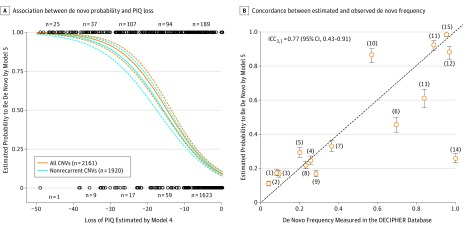

De Novo CNVs

In the neurodevelopmental clinic, de novo events are regarded as strong arguments in favor of pathogenicity, and CNV size was previously associated with de novo frequency.36 However, to our knowledge, the exact association between effect size on IQ and de novo frequency has not been studied. We examined inheritance of 2161 deletions 50 kb or larger from the CHU-SJ and SSC cohorts. The logistic regression model (model 5) suggests a tight association between effect size on IQ (estimated by model 4) and probability of being a de novo CNV (odds ratio, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.84-0.87; P = 2.7 × 10−88) (Figure 3A). Results are similar when recurrent CNVs are excluded. The concordance between the probability of occurring de novo estimated by model 5 and de novo frequency calculated using empirical data from the DECIPHER database on 15 recurrent deletions is 0.77 (95% CI, 0.43-0.91; P = 2.7 × 10−4) (https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/) (Figure 3B). We also examined 1147 CNVs 100 kb or larger in 837 adolescents and their parents from the general population (SYS). Seventeen occurred de novo (1.5%; 6 deletions and 11 duplications), which is similar to frequencies previously reported in the general population (eFigure 8 and eTables 18 and 19 in the Supplement). Among the 6 de novo deletions, 3 have never been referenced in the database of genomic variants, suggesting class 1 de novo events37 (eFigure 9B, cases 1, 5, and 6, in the Supplement). Although model 4 predicts a large effect of −28.7 points for the deletion in case 5, the predicted effect for cases 1 and 6 is less than 5 points, suggesting that among class 1 de novo events37 effect sizes can be modest. The 3 other CNVs (cases 2, 3, and 4) have general population frequencies greater than 0.01%, suggesting class 2 de novo events37 consistent with the small predicted associations with IQ.

Figure 3. Association Between De Novo and IQ Loss.

A, Probability of de novo estimated by model 5 (y-axis) according to the loss of performance IQ (PIQ) estimated by model 4 (x-axis) for the 897 deletions from the Center Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine cohort and 1264 deletions from the Simon simplex collection cohort for which inheritance status is available (the orange lines are all copy number variants [CNVs], and the gray lines are nonrecurrent CNVs). The de novo frequency increased even for modest associations with IQ (eg, −5 points of PIQ is associated with a de novo frequency of 7.8%). B, Concordance between de novo frequency observed in DECIPHER (x-axis) and the probability of being de novo estimated by model 5 (y-axis) for 15 recurrent CNVs. Each point corresponds to a known recurrent CNV: (1) 17p12_(HNPP), (2) 16p12.1, (3) 15q11.2, (4) 16p13.11, (5) 1q21.1 TAR, (6) 17q12, (7) 16p11.2 Distal (SH2B1), (8) 1q21.1 Distal (Class I), (9) 15q13.3 (BP4-BP5), (10) 16p11.2 proximal (BP4-BP5), (11) 22q11.2, (12) 7q11.23 (William-Beuren), (13) 3q29 (DLG1), (14) 8p23.1, and (15) 17p11.2 (Smith-Magenis). The first bisector represents the perfect concordance. ICC3,1 indicates intraclass correlation coefficient (1, 3).

Discussion

This study quantifies and predicts the effect size of deletions on IQ using data from the general population and clinical cohorts. Deletions are associated with a decrease in general intelligence, and our models suggest that the effect of haploinsufficiency can be reliably predicted for most pathogenic deletions. This approach provides a framework for studying the effect of CNVs that are too rare to study in individual association studies.

Our study suggests that haploinsufficiency of most of the coding genome potentially influences general intelligence, and one-third of the coding genome affects IQ by 0.67 points or more (mean effect of genes included in rare deletions). This finding is consistent with the omnigenic model37 of complex traits based on the observation that genome-wide association study association signals are spread across most of the genome, including variants near many genes without any obvious connection to disease.

This finding has important implications for the clinical interpretation and functional studies of CNVs. A dominant hypothesis that guides many studies is that a major gene(s) contributes to most of the neurodevelopmental symptoms observed in CNV carriers. Our study suggests an alternative hypothesis that the large effect size observed in pathogenic deletions may be polygenic in nature and attributable to the sum of small individual effects of each gene included in the deletion. This hypothesis could explain why causal genes or major drivers have been difficult to identify in most recurrent CNVs.38,39

Intriguingly, our model predicts reasonably the effect size of the Smith-Magenis deletion without attributing a large effect size to the RAI1 gene (OMIM 607642) on IQ. Although RAI1 causes most of the dysmorphic and disruptive behavioral features of Smith-Magenis syndrome,40 its association with IQ may be smaller than expected. Of note, a recent study41 did not identify an excess of de novo mutations in RAI1 in more than 7000 individuals with ID.

Large discordances between estimated and empirical estimates of IQ are of particular interest. For example, the model underestimates the effects of 15q13.3 and 3q29 deletions. This underestimation could be attributable to genes with large effect sizes, although none have been clearly identified in these CNVs by previous studies.35,41 Alternatively, the association of these 2 CNVs with IQ might be overestimated in the literature because carriers of these deletions are mostly referred to the clinic for behavioral or neurologic symptoms (eg, epilepsy). Although enrichment of the 17p12/hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies deletion was not previously reported in a neurodevelopmental cohort,7 our model predicts an IQ loss of 6 points. This finding is consistent with the enrichment observed in the CHU-SJ neurodevelopmental cohort (odds ratio, 3.25; 14 cases per 16 586; P = .002) and previous studies42,43,44 reporting association with schizophrenia (odds ratio ranging from 1 to 5).

Our study quantifies the association between the effect size of deletions on IQ and the frequency at which they occur de novo. The probability of occurring de novo increases rapidly for deletions with small effect sizes on IQ (a few points), reaching a frequency of 100% for effect sizes of 30 points or greater. The model’s prediction has a concordance of 0.75 with the de novo frequency of 15 recurrent CNVs calculated using empirical data. It is likely that many de novo deletions, which confer significant risk for NDDs, may lie on a continuum between class 1 and class 2 variants.37 In fact, most deletions that affect IQ have effect sizes of less than 30 points, are present in general population cohorts, and would be classified as class 2 de novo variants, which incorrectly reflects the risk they confer for NDDs.

Limitations

The predictive models presented in the study have several limitations. In particular, they are unable to attribute large effects to ID causal genes. This limitation is likely because calibration was performed in the general population (with too few cases of ID) and reliance on haploinsufficiency scores that were not intended to provide granularity among genes with large effects. Indeed, the model attributes a maximal effect of 2.74 points of PIQ loss, whereas causal genes for ID are associated with IQ loss between 40 and 60 points.35,41 On the other hand, it is likely that our model properly estimated small effect size because it was developed and calibrated in the general population based on a set of CNVs that contain genes with milder effects.

Conclusions

The association of deletions with IQ can be modeled using haploinsufficiency scores based on a linear and additive assumption. Observations in the general population can estimate the effect sizes of recurrent pathogenic CNVs identified in the clinic. Results suggest that the frequency of de novo events can reliably estimate the effect size of a deletion on IQ. This method represents a new framework to study variants too rare to perform individual association studies and can be useful to estimate the cognitive effect of undocumented deletions (http://www.minds-genes.org/Site_EN/CNVsPredictionTools.html) identified in the neurodevelopmental clinic. Larger sample sizes and more refined models in cohorts, including individuals with IDs, are likely required to model the effects of duplications.

eTable 1. Difference of IQ Between Male and Female in IMAGEN and SYS Cohorts

eTable 2. Breakpoints Used to Detect Recurrent CNVs

eTable 3. Empirical Data on Recurrent CNVs

eTable 4. Frequency of Rare Autosomal CNVs in IMAGEN and SYS Cohorts and Comparison With Mannik et al’s Cohort

eTable 5. Frequency of Rare X-linked CNVs in IMAGEN and SYS Cohorts

eTable 6. Comparison of Proportion of Rare Autosomal Deletions ≥250 kb, Duplications ≥1 Mb, and Recurrent CNVs Between Males and Females

eTable 7. Impact on IQ of Rare CNVs by Category of Size and Recurrent CNVs

eTable 8. Average of AIC and BIC for Models 1-3 Obtained by Bootstrap on Pooled Cohort

eTable 9. The Cumulative Effect on IQ of CNV Size, Number of Complete Genes, and Number of Exon (Models 1-3) on the Subset of Individuals With European Ancestry

eTable 10. Estimates of Model 4 in IMAGEN and SYS Cohorts

eTable 11. Results of Variables Selection, Performing on the Subset of 1713 Individuals From The Pooled Cohort Carrying at Least One Deletion, Using Bootstrap Stepwise Procedure Based on BIC in Multiple Linear Regression Where Dependent Variable Is Either the PIQ or VIQ and Candidate Predictors Are Deletion Contents

eTable 12. Results of PCA Analysis on Gene-Related Variables, Including the 1713 Individuals of the Pooled Cohort Having at Least One Deletion.

eTable 13. Results of Variables Selection, Performing on the Subset of 1713 Individuals From The Pooled Cohort Carrying at Least One Deletion, Using Bootstrap Stepwise Procedure Based on BIC in Multiple Linear Regression Where Dependent Variable Is Either the PIQ or VIQ and Candidate Predictors Are Deletion Contents After PCA for Related to Gene Variables

eTable 14. Results of Sensitivity Analyses for Models 1-3

eTable 15. Results of Sensitivity Analyses for Models 1-3 in the Subset of Adolescent With European Ancestry

eTable 16. Estimates and Sensitivity Analysis for Model 4

eTable 17. Table of Impact of IQ in CHU-SJ Cohorts by CNVs Classification

eTable 18. De Novo CNVs in SYS

eTable 19. De Novo in General Population

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eFigure 1. Representation of Ancestries Information for IMAGEN and SYS

eFigure 2. Definition of Shift of IQ and Threshold From Which a Subject Is Referred in Clinic

eFigure 3. Simulated Odds Ratios Based on Shift of IQ and Threshold From Which an Individual is Referred to Clinic

eFigure 4. Overlap Between Rare Recurrent and Nonrecurrent CNVs in IMAGEN and SYS Children

eFigure 5. Predicted Loss of VIQ for Recurrent CNVs and Nonrecurrent CNVs Observed in the Clinic

eFigure 6. Estimation of the Loss of PIQ for Each Gene Included in 16 Recurrent Deletions Known to Be Associated With Psychiatric Disorders

eFigure 7. Graph of Correlations Between Variables Included in Selection Procedure for Individuals Having at Least One Deletion (N=1713)

eFigure 8. Log R Ratio and B Allele Frequency for Children Having De Novo and Parents From SYS Cohort

eFigure 9. Effect on IQ of De Novo in SYS Cohort

eResults. Supplemental Results

eReferences

References

- 1.Huguet G, Ey E, Bourgeron T. The genetic landscapes of autism spectrum disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2013;14:191-213. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinto D, Delaby E, Merico D, et al. . Convergence of genes and cellular pathways dysregulated in autism spectrum disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94(5):677-694. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinto D, Pagnamenta AT, Klei L, et al. . Functional impact of global rare copy number variation in autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2010;466(7304):368-372. doi: 10.1038/nature09146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betancur C. Etiological heterogeneity in autism spectrum disorders: more than 100 genetic and genomic disorders and still counting. Brain Res. 2011;1380:42-77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakai M, Watanabe Y, Someya T, et al. . Assessment of copy number variations in the brain genome of schizophrenia patients. Mol Cytogenet. 2015;8(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s13039-015-0144-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szatkiewicz JP, O’Dushlaine C, Chen G, et al. . Copy number variation in schizophrenia in Sweden. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(7):762-773. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper GM, Coe BP, Girirajan S, et al. . A copy number variation morbidity map of developmental delay. Nat Genet. 2011;43(9):838-846. doi: 10.1038/ng.909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coe BP, Witherspoon K, Rosenfeld JA, et al. . Refining analyses of copy number variation identifies specific genes associated with developmental delay. Nat Genet. 2014;46(10):1063-1071. doi: 10.1038/ng.3092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maillard AM, Ruef A, Pizzagalli F, et al. ; 16p11.2 European Consortium . The 16p11.2 locus modulates brain structures common to autism, schizophrenia and obesity. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(1):140-147. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kearney HM, Thorland EC, Brown KK, Quintero-Rivera F, South ST; Working Group of the American College of Medical Genetics Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee . American College of Medical Genetics standards and guidelines for interpretation and reporting of postnatal constitutional copy number variants. Genet Med. 2011;13(7):680-685. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182217a3a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S, et al. . Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86(5):749-764. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders SJ, He X, Willsey AJ, et al. ; Autism Sequencing Consortium . Insights into autism spectrum disorder genomic architecture and biology from 71 risk loci. Neuron. 2015;87(6):1215-1233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stefansson H, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Steinberg S, et al. . CNVs conferring risk of autism or schizophrenia affect cognition in controls. Nature. 2014;505(7483):361-366. doi: 10.1038/nature12818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kendall KM, Rees E, Escott-Price V, et al. . Cognitive performance among carriers of pathogenic copy number variants: analysis of 152,000 UK Biobank subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;82(2):103-110. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uddin M, Pellecchia G, Thiruvahindrapuram B, et al. . Indexing effects of copy number variation on genes involved in developmental delay. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28663. doi: 10.1038/srep28663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Männik K, Mägi R, Macé A, et al. . Copy number variations and cognitive phenotypes in unselected populations. JAMA. 2015;313(20):2044-2054. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schumann G, Loth E, Banaschewski T, et al. ; IMAGEN consortium . The IMAGEN study: reinforcement-related behaviour in normal brain function and psychopathology. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(12):1128-1139. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pausova Z, Paus T, Abrahamowicz M, et al. . Cohort profile: the Saguenay Youth Study (SYS). Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(2):e19. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufman AS, Flanagan DP, Alfonso VC, Mascolo JT. Test review: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV). J Psychoeduc Assess. 2006;24(3):278-295. doi: 10.1177/0734282906288389 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canivez GL, Watkins MW. Long-term stability of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Third Edition among demographic subgroups: gender, race/ethnicity, and age. J Psychoed Assess. 1999;17(4):300-313. doi: 10.1177/073428299901700401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders SJ, Ercan-Sencicek AG, Hus V, et al. . Multiple recurrent de novo copy number variations (CNVs), including duplications of the 7q11.23 Williams-Beuren syndrome region, are strongly associated with autism. Neuron. 2011;70(5):863-885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. . PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang K, Li M, Hadley D, et al. . PennCNV: an integrated hidden Markov model designed for high-resolution copy number variation detection in whole-genome SNP genotyping data. Genome Res. 2007;17(11):1665-1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.6861907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colella S, Yau C, Taylor JM, et al. . QuantiSNP: an Objective Bayes Hidden-Markov Model to detect and accurately map copy number variation using SNP genotyping data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(6):2013-2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. ; Exome Aggregation Consortium . Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536(7616):285-291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrovski S, Gussow AB, Wang Q, et al. . The intolerance of regulatory sequence to genetic variation predicts gene dosage sensitivity. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(9):e1005492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruderfer DM, Hamamsy T, Lek M, et al. ; Exome Aggregation Consortium . Patterns of genic intolerance of rare copy number variation in 59,898 human exomes. Nat Genet. 2016;48(10):1107-1111. doi: 10.1038/ng.3638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, et al. . STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D447-D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawrylycz M, Miller JA, Menon V, et al. . Canonical genetic signatures of the adult human brain. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(12):1832-1844. doi: 10.1038/nn.4171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bayés A, van de Lagemaat LN, Collins MO, et al. . Characterization of the proteome, diseases and evolution of the human postsynaptic density. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(1):19-21. doi: 10.1038/nn.2719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darnell JC, Van Driesche SJ, Zhang C, et al. . FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell. 2011;146(2):247-261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramasamy A, Trabzuni D, Guelfi S, et al. ; UK Brain Expression Consortium; North American Brain Expression Consortium . Genetic variability in the regulation of gene expression in ten regions of the human brain. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(10):1418-1428. doi: 10.1038/nn.3801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vrieze SI. Model selection and psychological theory: a discussion of the differences between the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Psychol Methods. 2012;17(2):228-243. doi: 10.1037/a0027127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(2):420-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright CF, Fitzgerald TW, Jones WD, et al. ; DDD study . Genetic diagnosis of developmental disorders in the DDD study: a scalable analysis of genome-wide research data. Lancet. 2015;385(9975):1305-1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61705-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Itsara A, Wu H, Smith JD, et al. . De novo rates and selection of large copy number variation. Genome Res. 2010;20(11):1469-1481. doi: 10.1101/gr.107680.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kosmicki JA, Samocha KE, Howrigan DP, et al. . Refining the role of de novo protein-truncating variants in neurodevelopmental disorders by using population reference samples. Nat Genet. 2017;49(4):504-510. doi: 10.1038/ng.3789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prasad SE, Howley S, Murphy KC. Candidate genes and the behavioral phenotype in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2008;14(1):26-34. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakurai T, Dorr NP, Takahashi N, McInnes LA, Elder GA, Buxbaum JD. Haploinsufficiency of Gtf2i, a gene deleted in Williams Syndrome, leads to increases in social interactions. Autism Res. 2011;4(1):28-39. doi: 10.1002/aur.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Girirajan S, Vlangos CN, Szomju BB, et al. . Genotype-phenotype correlation in Smith-Magenis syndrome: evidence that multiple genes in 17p11.2 contribute to the clinical spectrum. Genet Med. 2006;8(7):417-427. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000228215.32110.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McRae JF, Clayton S, Fitzgerald TW, et al. ; Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study . Prevalence and architecture of de novo mutations in developmental disorders. Nature. 2017;542(7642):433-438. doi: 10.1038/nature21062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rees E, Kendall K, Pardiñas AF, et al. . Analysis of intellectual disability copy number variants for association with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(9):963-969. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malhotra D, Sebat J. CNVs: harbingers of a rare variant revolution in psychiatric genetics. Cell. 2012;148(6):1223-1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marshall CR, Howrigan DP, Merico D, et al. ; Psychosis Endophenotypes International Consortium; CNV and Schizophrenia Working Groups of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium . Contribution of copy number variants to schizophrenia from a genome-wide study of 41,321 subjects. Nat Genet. 2017;49(1):27-35. doi: 10.1038/ng.3725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Difference of IQ Between Male and Female in IMAGEN and SYS Cohorts

eTable 2. Breakpoints Used to Detect Recurrent CNVs

eTable 3. Empirical Data on Recurrent CNVs

eTable 4. Frequency of Rare Autosomal CNVs in IMAGEN and SYS Cohorts and Comparison With Mannik et al’s Cohort

eTable 5. Frequency of Rare X-linked CNVs in IMAGEN and SYS Cohorts

eTable 6. Comparison of Proportion of Rare Autosomal Deletions ≥250 kb, Duplications ≥1 Mb, and Recurrent CNVs Between Males and Females

eTable 7. Impact on IQ of Rare CNVs by Category of Size and Recurrent CNVs

eTable 8. Average of AIC and BIC for Models 1-3 Obtained by Bootstrap on Pooled Cohort

eTable 9. The Cumulative Effect on IQ of CNV Size, Number of Complete Genes, and Number of Exon (Models 1-3) on the Subset of Individuals With European Ancestry

eTable 10. Estimates of Model 4 in IMAGEN and SYS Cohorts

eTable 11. Results of Variables Selection, Performing on the Subset of 1713 Individuals From The Pooled Cohort Carrying at Least One Deletion, Using Bootstrap Stepwise Procedure Based on BIC in Multiple Linear Regression Where Dependent Variable Is Either the PIQ or VIQ and Candidate Predictors Are Deletion Contents

eTable 12. Results of PCA Analysis on Gene-Related Variables, Including the 1713 Individuals of the Pooled Cohort Having at Least One Deletion.

eTable 13. Results of Variables Selection, Performing on the Subset of 1713 Individuals From The Pooled Cohort Carrying at Least One Deletion, Using Bootstrap Stepwise Procedure Based on BIC in Multiple Linear Regression Where Dependent Variable Is Either the PIQ or VIQ and Candidate Predictors Are Deletion Contents After PCA for Related to Gene Variables

eTable 14. Results of Sensitivity Analyses for Models 1-3

eTable 15. Results of Sensitivity Analyses for Models 1-3 in the Subset of Adolescent With European Ancestry

eTable 16. Estimates and Sensitivity Analysis for Model 4

eTable 17. Table of Impact of IQ in CHU-SJ Cohorts by CNVs Classification

eTable 18. De Novo CNVs in SYS

eTable 19. De Novo in General Population

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eFigure 1. Representation of Ancestries Information for IMAGEN and SYS

eFigure 2. Definition of Shift of IQ and Threshold From Which a Subject Is Referred in Clinic

eFigure 3. Simulated Odds Ratios Based on Shift of IQ and Threshold From Which an Individual is Referred to Clinic

eFigure 4. Overlap Between Rare Recurrent and Nonrecurrent CNVs in IMAGEN and SYS Children

eFigure 5. Predicted Loss of VIQ for Recurrent CNVs and Nonrecurrent CNVs Observed in the Clinic

eFigure 6. Estimation of the Loss of PIQ for Each Gene Included in 16 Recurrent Deletions Known to Be Associated With Psychiatric Disorders

eFigure 7. Graph of Correlations Between Variables Included in Selection Procedure for Individuals Having at Least One Deletion (N=1713)

eFigure 8. Log R Ratio and B Allele Frequency for Children Having De Novo and Parents From SYS Cohort

eFigure 9. Effect on IQ of De Novo in SYS Cohort

eResults. Supplemental Results

eReferences