Abstract

Background

About 5%–10% of breast cancer and 10%–15% of ovarian cancer are hereditary. BRCA1 and BRCA2 are the most common germline mutations found in both inherited breast and ovarian cancers. Once these mutations are identified and classified, a course of action to reduce the risk of developing either ovarian or breast cancer – including surveillance and surgery – is carried out.

Purpose

The purpose of the current research is to characterize the gene expression differences between healthy cells harboring a mutation in BRCA1/2 genes and normal cells. This will allow detection of candidate genes and help identify women who carry functional BRCA1/2 mutations, which cannot always be detected by the available sequencing methods, for example, carriers of mutations found in regulatory sequences of the genes.

Materials and methods

Our cohort consisted of 50 healthy women, of whom 24 were individuals with BRCA1 or BRCA2 heterozygous mutations and 26 were non-carrier controls. RNA purified from non-irradiated lymphocytes of nine BRCA1/2 mutation carriers versus four control mutation-negative individuals was utilized for RNA-Seq analysis. The selected RNA-Seq transcripts were validated, and the levels of spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) mRNA were measured by using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Results

Differences in gene expression were found when comparing untreated lymphocytes of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers and controls. Among others, the SYK gene was identified as being differently expressed for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. The expression level of SYK was significantly higher in untreated healthy lymphocytes of BRCA1 heterozygote carriers compared with controls, regardless of irradiation. In contrast to normal tissues, in cancerous breast tissues, the expression levels of the BRCA1 and SYK genes were not intercorrelated.

Conclusion

Collectively, our observations demonstrate that SYK may prove to be a good candidate for better diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of BRCA1 mutation-associated breast cancer.

Keywords: RNA-Seq, breast cancer susceptibility, peripheral blood

Introduction

The presence of mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes increases a woman’s susceptibility to develop breast and ovarian cancers by the age of 70, with the incidence ranging between 47% and 66%, and 40% and 57%, respectively.1,2 Additionally, women with a BRCA mutation have an elevated risk of developing other malignancies, such as gastrointestinal cancers (e.g., gall bladder, bile duct, colon, stomach, pancreas) and melanoma, and when this mutation appears in males, it increases the risk for breast and prostate cancers.3,4

The BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins are involved in different cellular processes, including homologous recombination of DNA repair,5,6 ubiquitination, chromosomal segregation,7 cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and gene transcription. In addition, they are required for the S phase and G2/M checkpoint arrest in response to DNA damage.8–10 Abnormal BRCA1 and BRCA2 expression interferes with routine cell cycle events such as cell division, death, or life span. Therefore, these genes are recognized as “gatekeeper” genes, whose mutation stimulates the progression of cancer.11

Although the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes were identified a long time ago, their specific biological mechanisms and the way disruptions of their functions promote breast and ovarian carcinogenesis remain unclear. According to Knudson’s widely accepted “two-hit” hypothesis,12 inheriting one de novo germline copy of a mutated BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene (i.e., the so-called first hit) is insufficient to enable the development of breast cancer and other hereditary cancer syndromes. The acquisition of a “second hit” to the remaining “healthy” copy of the gene is required for cancer development. This mutation can occur somatically, leading to the loss of both copies of the normal tumor suppressor gene. Notwithstanding, several studies support the idea that haploinsufficiency itself can interrupt normal cell function by contributing to genome instability, which leads to additional cancer driver mutations. For example, mice carrying a heterozygous mutation in the BRCA1 gene have shortened life spans and are more susceptible to ovarian cancer following ionizing irradiation without losing the other BRCA1 allele.13 Such findings suggest that women carrying BRCA1 mutations may be more susceptible to ovarian tumor formation after irradiation than non-mutation carriers.

Different cell types, such as normal fibroblasts14 and ovarian and breast epithelial cells15 from heterozygous BRCA1 mutation carriers, display a different gene expression profile than controls in response to DNA damage, again suggesting that BRCA heterozygosity itself contributes to breast cancer initiation. Moreover, it was found that losing a single allele of BRCA1 contributes specifically to alteration in the expression of genes having a role in cellular differentiation.16 This finding supports the hypothesis that single copy loss of BRCA1 may cause variations in cell differentiation and, eventually, causes cells to undergo malignant processes.16 Our previous study demonstrated the differences in gene expression in lymphocytes subject to ionizing radiation derived from BRCA mutation carriers as compared with controls, confirming a measurable heterozygous effect.17 Finally, it has been shown using fluorescence lifetime (FLT) imaging microscopy, a method used to differentiate between distinct cell populations, that lymphocytes derived from control or BRCA1 mutation carriers differ in their FLT values from lymphocytes derived from BRCA2 mutation carrier individuals. This study demonstrates that BRCA1 and BRCA2 heterozygous lymphocytes have innate differences independent of irradiation. In addition, it suggests that these heterozygous mutations can lead to changes in the physical properties of the cells themselves, such as pH, temperature, viscosity, and oxygen concentration.18

In the current study, we wished to extend our previous research and examine whether there is a difference in gene expression in untreated cells from BRCA carriers and controls. The spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) gene was identified as differently expressed in BRCA1 mutation carriers. The results of this study will allow for a more accurate characterization of intrinsic differences between healthy cells harboring a mutation in BRCA1/2 genes and normal cells. Moreover, our observations demonstrate that SYK could prove to be a good candidate for more effective diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of BRCA1 mutation-associated breast cancer.

Materials and methods

Sample information

Our cohort consisted of 50 healthy women aged between 25 and 50 years, of whom 24 were individuals with no personal history of cancer but with BRCA1 or BRCA2 heterozygous mutations and 26 women had no BRCA mutations. Note that some of the subjects in the various analyses (RNA-Seq and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction [qPCR]) in this study overlap. The mutation carriers were diagnosed in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 predictive testing program of the Oncogenetic Clinic of Hadassah University Medical Center (Jerusalem, Israel).

The women in the study who served as controls needed to fulfill two conditions. The first one was the absence of any personal or familial history of breast or ovarian cancer in the participants. Second, they needed to be non-carriers of known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations.

The local Ethics Committee of Hadassah Medical Center approved the study protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from all participating individuals before inclusion in the study.

Lymphocyte extraction and preparation

Lymphocyte extraction and treatment were conducted as previously described.17 In summary, primary lymphocyte cells were obtained from peripheral blood using LymphoPrep (Sigma) and short-term cultured for 6 days in RPMI-1640 with l-glutamine (Biological Industries), supplemented with interleukin-2, 15% fetal calf serum, 1% 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. One day following lymphocyte extraction, half of each sample was γ-irradiated with 8 Gy at a high-dose rate (0.86 Gy/min, Orthovoltage X-ray machine), as previously described.19 Although this dose exceeds the portion used in classical radiotherapy or screening radiation, the DNA damage it causes presumably mimics the additive effect of repeated radiation exposure, which usually occurs in the clinic.9 Additionally, we chose this dose based on our previous study showing differences in gene expression in BRCA mutation carriers after ionizing radiation.17

Gene expression analysis

Poly(A)-selected RNA was sequenced using the Illumina TruSeq protocol on the HiSeq 2500 sequencing machine. Quality control checks on the raw sequence data were carried out using the FastQC tool (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Then, the Trim Galore! tool (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/), which is based on cutadapt,20 was used for adapter trimming and for removing low-quality bases from the ends of reads. Clean reads were mapped to the human genome (hg38) using tophat2.21 Next, the number of reads mapping each human gene (as annotated in Ensembl release 77) was counted using the “union” mode of HTseq-count script.22 Differential expression analysis was performed using the edgeR and Limma packages from the Bioconductor framework.23 Briefly, features with <1 read per million in at least five samples were removed. The remaining gene counts were normalized using the trimmed mean of M values method, followed by voom transformation.24,25 Linear models, as implemented by the Limma package,23 were used to find differentially expressed genes. Since FDR application was too stringent for this data set, genes with a P-value <0.001 were considered as differentially expressed. Gene set enrichment and pathway analysis were done using GeneAnalytics.26

RNA extraction and real-time qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from primary lymphocyte cells using a Direct-zol™ RNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research), according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. Complementary DNA was obtained by reverse transcription of 850 ng of total RNA in a final reaction volume of 20 μL containing 4 μL qScript Reaction Mix and 1 μL qScript Reverse Transcriptase (Quantabio). Quantitative real-time PCR assays containing the primers (Table S1) and probe mix for SYK, TSPAN18, DPEPT, and OTUB2 were purchased from Biosearch Technologies and utilized according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was carried out in a final reaction volume of 10 μL containing 20 ng of complementary DNA template, 5 μL of PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix, ROX (Quantabio), and 1 μL of primers mix. All reactions were run in triplicate, and the housekeeping genes, GAPDH (Figure S1) and beta-actin (Figure S2), were amplified in a parallel reaction for normalization.

Analysis of publicly available ICGC and GTEx expression data

The expression values of BRCA1, BRCA2, and SYK genes across the breast tissues taken from healthy donors and patients with breast cancer (available from the GTEx27 and ICGC28 databases, respectively) were visualized using the UCSC Xena genome browser.29 In each database, samples were divided into two groups based on the expression of BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes using the median value as the cutoff point. The chart view option in Xena was used to view the distribution of SYK expression across the two groups and to calculate the Welch’s t-test. Mean centered values of the normalized SYK expression were downloaded and box plots were generated using R language.

Results

Characterizing the mRNA expression profile in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers versus non-carrier controls

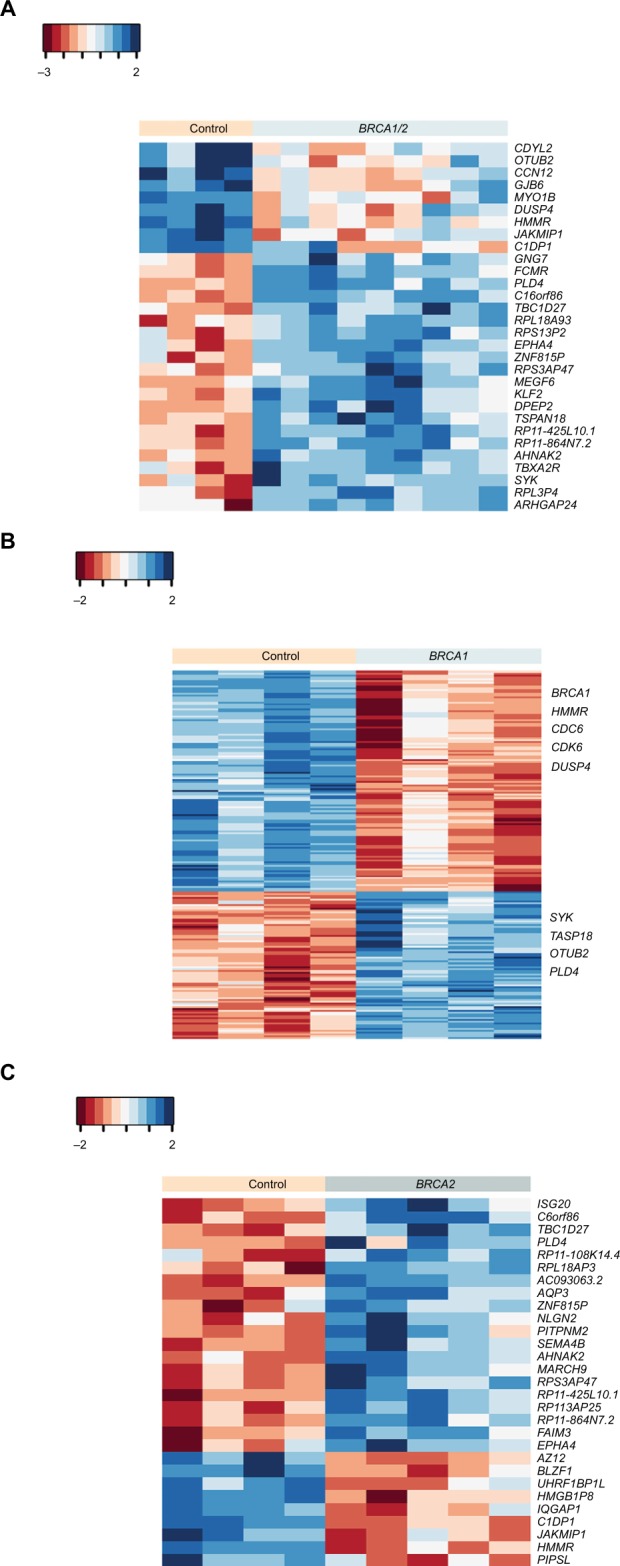

In a previous study, we tested whether BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers could be distinguished from control mutation-negative individuals based on gene expression changes triggered by the activation of BRCA1/2 genes following irradiation.17 As opposed to the previous study, herein, we tested for differences in basal gene expression in these groups using non-irradiated lymphocytes. We used an RNA-Seq analysis on lymphocyte-derived RNA to evaluate the gene expression in BRCA1 and BRCA2 heterozygous mutants and mutation-free individuals. The mutation types identified in carriers used in this study are summarized in Table 1. Notably, all the mutations are known to be functional and contribute to the risk of developing breast cancer. When comparing the control group to BRCA1/2 together, 30 genes were significantly differentially expressed (P<0.001; Figure 1A; Table S2). Furthermore, when we did a separate statistical analysis on BRCA1 and BRCA2, as compared with the control group, we were able to identify 203 genes in BRCA1 and 29 genes in BRCA2 that were differentially expressed (Figure 1B and 1C; Table S2).

Table 1.

Mutation data of patients enrolled in the study

| Mutation | Number of individuals |

|---|---|

| BRCA1-185del AG | 8 |

| BRCA1-5382 ins C | 1 |

| BRCA1-Q356R | 1 |

| BRCA1-p.P1812A | 1 |

| BRCA2-6174delT | 10 |

| BRCA2-c.6024dupG | 1 |

| BRCA2-R2336p | 1 |

| BRCA2-IVS2+1G>A | 1 |

Figure 1.

Basal gene expression profile in BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutation carriers versus non-carriers.

Notes: Heat map of hierarchical cluster analysis showing 30 DE genes (P<0.001, fold change ≥2) between BRCA1/2 mutation carriers and control samples (n=4–5/group) (A), 203 DE genes (P<0.001) between BRCA1 mutation carriers and controls (B), and 29 DE genes (P<0.001) between BRCA2 carriers versus non-carriers (C). Red indicates a decrease in gene expression, while blue indicates an increase. Euclidean distance was used as the distance method and complete linkage as the agglomeration method.

Abbreviation: DE, differentially expressed.

Differently expressed genes that may predict BRCA1 status, but not BRCA2, indicate defects in DNA repair

To further understand the underlying biology leading to the classification schemes (Figure 1), we used the GeneAnalytics application26 to enable us to examine the networks formed from the differentially regulated genes in BRCA1 mutation carriers.

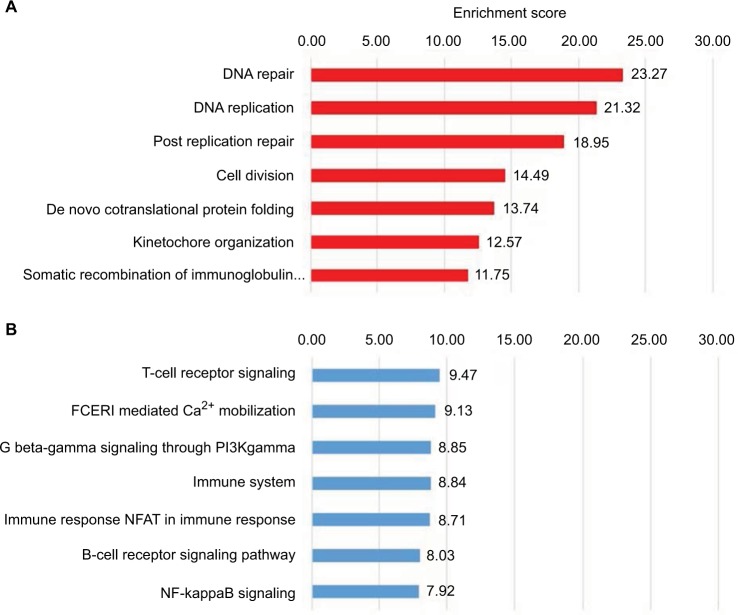

Genes differentially expressed in BRCA1 mutation carriers versus control (Figure 1B) are involved in tumorigenic-related pathways (Figure 2). Most of these genes (122) are downregulated and are involved in critical cellular functions, including cell division, DNA replication, and DNA repair (Figure 2A). Analysis of 81 upregulated genes revealed over-representation of genes involved in the T-cell receptor signaling, immune system, and B-cell receptor signaling pathway (Figure 2B). Surprisingly, although the BRCA2 gene has been implicated in a diverse array of cellular functions, including DNA repair, differential gene expression among BRCA2 mutation carriers and controls revealed only 29 differently expressed genes (Figure 1C), none of which indicated any significant defects in DNA repair or other cellular signaling (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Analysis of genes predicting BRCA1 status.

Notes: GeneAnalytics analysis of the 203 genes differentially regulated in cells derived from BRCA1 mutation carriers in the RNA-Seq data. One hundred and twenty-two downregulated (A) and 81 upregulated (B) genes were subjected to enrichment analysis of Gene Ontologies–Biological Processes.

Abbreviations: NFAT, nuclear factors of activated T-cells; FCERI, Fc epsilon receptor.

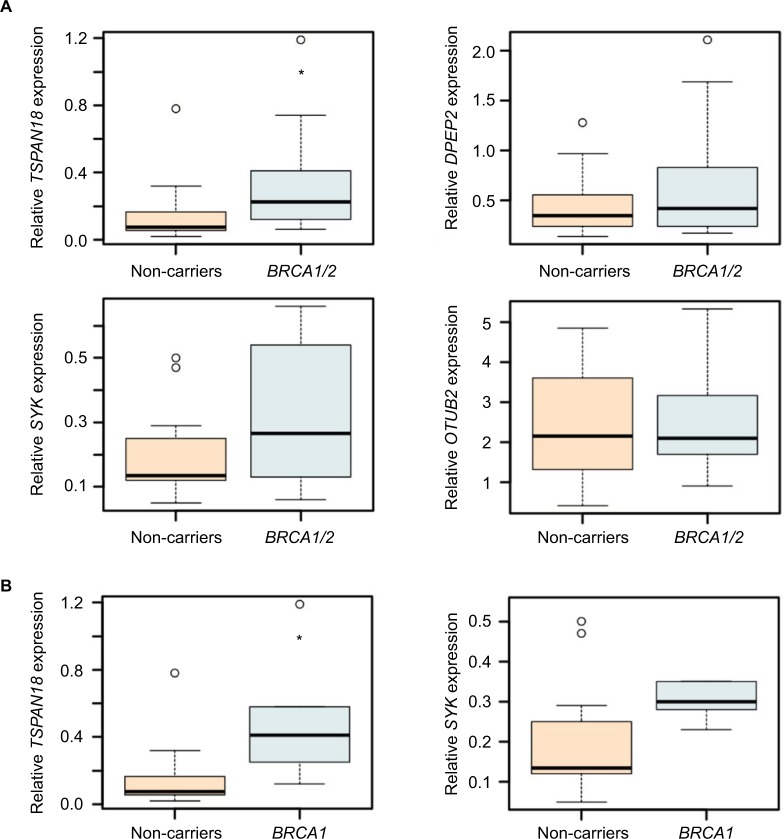

Validation of selected RNA-Seq transcripts by real-time qPCR

To ensure technical reproducibility and to validate our observation, we conducted a real-time qPCR analysis of those transcripts identified as significantly differently expressed for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, and their expression levels in samples were relatively high. Lymphocytes were obtained from 12 control mutation-negative individuals and 14 BRCA1/2 mutation carriers (Table 1). RNA was prepared and subjected to the SYBR Green assay for the indicated target genes. As presented in Figure 3A, although the expression of TSPAN18, SYK, and DPEPT showed consistency between RNA-Seq and real-time qPCR-based approaches in terms of overall average expression values across multiple samples, these differences were statistically significant only for TSPAN18. No variations in OTUB2 gene expression were observed among the different groups. Comparing the control mutation-negative individuals to BRCA1 mutation carriers only (Figures 3B and 4A) revealed significant differences in the expression of TSPAN18 and SYK.

Figure 3.

Predictive transcripts for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers.

Notes: Distribution of OTUB2, TSPAN18, SYK, and DPEPT expression levels in lymphocytes of 12 control mutation-negative individuals and 14 BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, as determined by real-time qPCR (A). Distribution of TSPAN18 and SYK expression levels across lymphocytes of mutation-negative individuals (n=12) and BRCA1 mutation carriers (n=5) (B). GAPDH was used for normalization (Figure S1). *P<0.05, calculated using Student’s t-test.

Abbreviations: qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase.

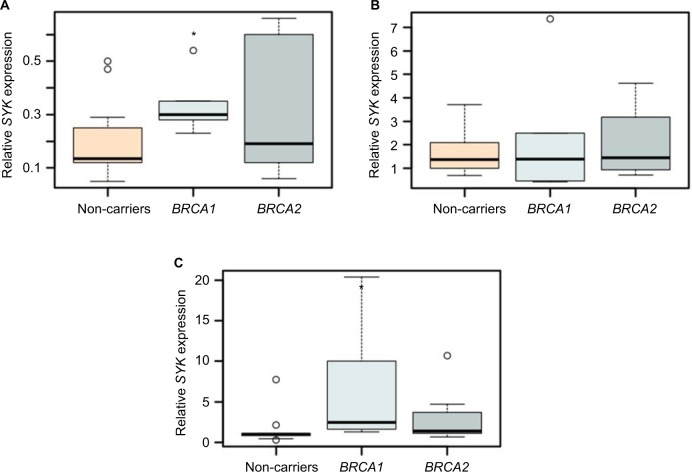

Figure 4.

SYK expression levels may distinguish control from BRCA1-mutated lymphocytes.

Notes: The box plots represent the expression of SYK in lymphocytes of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers and controls without irradiation (A) and at 1 hour (B) and 6 days (C) following irradiation, as determined by real-time qPCR. GAPDH was used for normalization. (n=4–12/group). For all experiments, *P<0.05, calculated using Student’s t-test.

Abbreviations: qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase.

SYK expression levels may distinguish control from BRCA1-mutated lymphocytes

Oxidative stress of B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells following ionizing radiation leads to the activation of PLK1 protein kinase, which then turns on the SYK protein.30,31 Since accumulating evidence suggests that BRCA1 and BRCA2 regulate ionizing radiation-induced oxidative stress,32 we hypothesized that the mutation status of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes directly affects the SYK expression profile following irradiation. We tested this hypothesis by examining the levels of SYK mRNA in control mutation-negative individuals and BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers using irradiated human lymphocytes.

For this purpose, primary lymphocytes obtained from peripheral blood were γ-irradiated with 8 Gy. RNA was extracted from the lymphocytes of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers and controls 1 hour following irradiation (10 and 11 subjects per group, respectively) and from lymphocytes of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers and controls, 6 days following irradiation (17 and 10 subjects per group, respectively), and a real-time qPCR analysis was conducted.

Our results demonstrate that, 6 days post-ionizing irradiation, the expression of SYK was, indeed, significantly upregulated in the lymphocytes of BRCA1 heterozygote carriers, as compared with controls. In contrast, 1 hour following irradiation, there were no differences in the expression levels of the gene among the different groups (Figures 4B–C and S2). Notably, even without irradiation, the expression of SYK was significantly upregulated in short-term cultured lymphocytes of BRCA1 mutation carriers, as compared with BRCA2 (Figures 3B and 4A).

Expression pattern of BRCA1/2 and SYK in patients with breast cancer

SYK is also expressed in the breast tissue.33 Considerable evidence demonstrates that SYK functions as a tumor suppressor in this tissue. Taking into account our results with lymphocytes, which provide evidence for a link between SYK expression and heterozygous BRCA1/2 mutations, and the known fact that SYK plays a critical role in breast cancer, an effort was made to identify correlations between the expression pattern of BRCA1/2 and SYK genes in breast cancer.

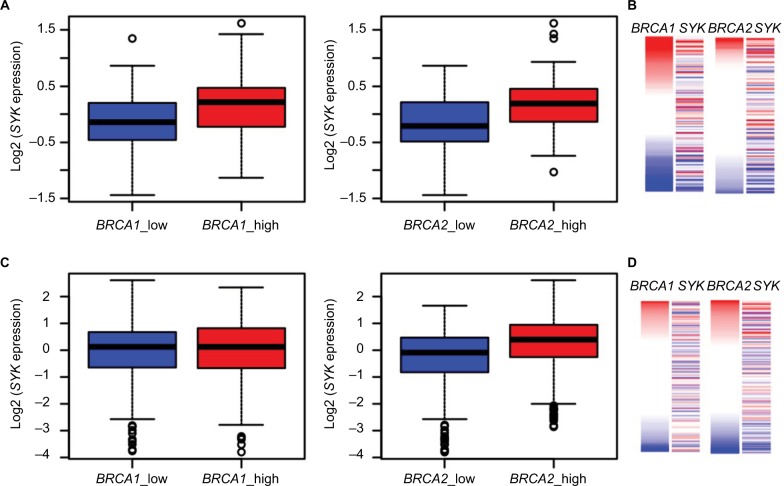

To accomplish this aim, we first analyzed the published GTEx dataset to gain a view on BRCA1, BRCA2, and SYK gene expression in normal breast tissues. As shown in Figure 5A and 5B, we found that samples having low BRCA1 or BRCA2 expression exhibit lower SYK expression and vice versa. Next, we analyzed the ICGC datasets of breast tumors. This analysis showed that, in contrast to normal tissues, the expression levels of the BRCA1 and SYK genes were not intercorrelated in breast samples from patients with ductal or lobular breast cancer (Figure 5C and 5D). Conversely, the expression levels of BRCA2 in these tissues were positively correlated with those of SYK, which was similar to the expression pattern of these genes in healthy breast tissues (Figure 5C and 5D). Taken together, our observations suggest that determining the expression levels of both BRCA1 and SYK in the same tumor may be clinically significant.

Figure 5.

Association between BRCA2 and SYK expression in normal and cancerous breast tissues.

Notes: Healthy breast tissues (n=214) from the GTEx database (A, B) and breast cancer samples (n=943) from the ICGC database (C, D) were divided into two groups based on the expression of BRCA1 (A, C) and BRCA2 (B, D) genes, using the median as the cutoff point. The box plots display the expression distribution of SYK across these groups. Higher SYK expression was detected in healthy breast tissues exhibiting an increased level of BRCA1 (A) P=2.391×10−6 and BRCA2 expression (B) P=5.122×10−7. In cancerous breast tissues, this association is preserved for BRCA2 (D) P=6.198×10−15, but not for BRCA1 (C) P=1.000.

Abbreviation: SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase.

Discussion

Our RNA-Seq analysis demonstrates that when a group of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers are compared to BRCA mutation-free controls, genes are differentially expressed (Figure 1). However, larger and more significant differences were found in the comparison between BRCA1 mutation carriers and control groups, and these include many functionally crucial genes, such as SLF1, MSH2, MSH6, CLSPN, TOPBP1, UBE2A, BRCA1, and others involved in DNA repair and replication pathways. Previously, Vuillaume et al34 attempted to identify BRCA1 mutation carriers based on the gene expression pattern in peripheral blood lymphocytes. Unlike our results, they found no significant difference in gene expression patterns between BRCA1 mutation carriers and controls. We assume that we were able to distinguish BRCA1 mutation carriers from non-carriers because we used RNA-Seq technology, which has superior benefits over microarray analyses in transcriptome profiling.35 Furthermore, in our study, short-term lymphocyte cultures were established for 6 days after obtaining the cells, instead of immediate RNA isolation. By doing so, lymphocyte populations became less heterogeneous between samples obtained from different individuals, and the results were affected mainly by BRCA carrier status rather than other factors associated with the donor of the lymphocytes.

It is already known that BRCA1 and BRCA2 have distinct functions in DNA repair following ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage and are key players at different stages of homologous recombination, which provides a mechanism to precisely repair damage.36 Therefore, it is not surprising that, after irradiation, the gene expression profile differs, based on which of the two BRCA genes is mutated.17 However, here, we demonstrate, for the first time, that even without irradiation, BRCA1- and BRCA2-mutated cells differ in their gene expression profiles. These results corroborate our previous findings, in which cells carrying the BRCA1 mutation showed higher FLT values than those carrying BRCA2, suggesting an intrinsic difference between the carriers of the two mutations.18

Overall, greater differences in gene expression, in terms of the number and type of genes, were observed when comparing BRCA1, but not BRCA2, mutation carriers to the control group. These differences may be explained because the BRCA1 gene itself is downregulated in BRCA1 mutation carriers compared with controls, while the BRCA2 gene is not altered in BRCA2 mutation carriers (Figure 1B).

The available methods for identifying BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers are based on sequencing approaches and do not detect all functional mutations (e.g., carriers with regulatory mutations, which are found in regulatory sequences of the genes). Previously, we suggested a functional diagnostic tool for identifying BRCA mutation carriers by using fresh lymphocytes.17 However, this approach cannot be easily applied since it requires irradiation of fresh lymphocytes by an X-ray machine, which is not available in most medical centers. Here, we demonstrate the potential of using real-time qPCR analysis in setting up a functional screening tool for BRCA1 mutation carriers in untreated accessible blood lymphocytes. Further studies in larger cohorts are needed to identify a set of specific genes to be used by this tool and verify its clinical efficacy. As presented in Figure 3, the SYK gene is a major candidate to be used by this tool. SYK is primarily expressed in hematopoietic cells. In lymphoid cells, this protein tyrosine kinase regulates several signaling pathways and is of great importance in B-cell receptor signaling, functioning as the main downstream effector protein. It has been shown that ionizing radiation in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells leads to oxidative stress and the activation of PLK1 protein kinase, which induces SYK enzymatic activity.30,31 In addition to our findings showing that SYK expression levels can distinguish controls from BRCA1-mutated lymphocytes, the study of gene activity in BRCA carriers may have other clinical implications, especially as SYK functions as a tumor suppressor.33,37 As shown in Figure 4, SYK expression level was significantly higher in lymphocytes of BRCA1 heterozygote carriers, as compared with controls, regardless of irradiation. Six days following the ionizing irradiation, the differences were even greater and more significant. A similar phenomenon can also be seen in normal breast tissue where samples with low BRCA1 expression exhibit lower SYK expression and vice versa. In contrast, in cancerous breast tissues, the situation is different; no link was found between the expression levels of the two genes, BRCA1 and SYK (Figure 5). We assume that, in healthy lymphocytes, the oxidative stress due to a mutation in BRCA1 increases, especially after ionizing irradiation, but a corresponding increased level of SYK expression and its suppressor function help maintain normal cell activity. Furthermore, in normal breast tissue, since both SYK and BRCA1 are tumor suppressors, we are not surprised that their expression pattern is similar. However, in cancerous tissues, such as breast tumors, even though BRCA1 is lowly expressed, the lack of corresponding increase in SYK expression supports the disruption of normal cellular activity, thus contributing to tumor formation and progression. In addition to research indicating a clear link between mutations in BRCA1 and the development of breast cancer,2 this hypothesis is supported by various studies demonstrating that SYK is expressed in normal human breast tissue, and in benign breast lesions and low-tumorigenic breast cancer cell lines.37,40 However, in the case of invasive breast carcinoma tissues and cell lines, the expression of SYK mRNA and protein is low compared to normal expression. This reduced SYK expression increases the risk of distant metastasis and also causes a poorer prognosis in a few tumor types, including breast carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, oral squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma.38

From a clinical perspective, the prognostic usefulness of reduced SYK levels in BRCA1 mutation and/or lowly expressed BRCA1-associated breast cancer should be investigated.

In normal breast tissue, when the expression levels of BRCA2 are low, the expression levels of SYK are correspondingly low and vice versa. Unlike BRCA1, in breast tumors, BRCA2 and SYK behave similarly – when the expression level of one is high, the other one is highly expressed and vice versa (Figure 5). These results again support the notion that both proteins, BRCA1 and BRCA2, have distinct functions in DNA repair and cell cycle progression.

Finally, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors represent a promising strategy for treating BRCA-associated cancers harboring specific DNA repair defects.39 However, we still need to investigate and understand the proper use of these agents. Some of the challenges that we face include identifying predictive biomarkers of response, which may be used for selecting a subset of patients who would maximally benefit from treatment with this novel agent; determining optimal dose and schedule; and establishing efficacy as a single agent or in combination with other chemotherapeutics. Since SYK expression increases due to oxidative stress and DNA damage, we assume that patients expressing high levels of SYK mRNA will respond better to treatment with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors.

Conclusion

Collectively, our observations demonstrate that SYK may be a good candidate for better diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of BRCA1 mutation-associated breast cancer. However, more detailed studies are needed to gain a clearer picture regarding the role of SYK in the pathogenesis of BRCA mutation-associated tumors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant number 1702/12) and the Israel Cancer Association Fund (grant number ICA 20130179) and the Ariel Center for Applied Cancer Research, Ariel University.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Stoppa-Lyonnet D. The biological effects and clinical implications of BRCA mutations: where do we go from here? Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24(Suppl 1):S3–S9. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen S, Parmigiani G. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1329–1333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson D, Easton D. The genetic epidemiology of breast cancer genes. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2004;9(3):221–236. doi: 10.1023/B:JOMG.0000048770.90334.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mersch J, Jackson MA, Park M, et al. Cancers associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations other than breast and ovarian. Cancer. 2015;121(2):269–275. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moynahan ME, Chiu JW, Koller BH, Jasin M. Brca1 controls homology-directed DNA repair. Mol Cell. 1999;4(4):511–518. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tutt A, Bertwistle D, Valentine J, et al. Mutation in Brca2 stimulates error-prone homology-directed repair of DNA double-strand breaks occurring between repeated sequences. EMBO J. 2001;20(17):4704–4716. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starita LM, Machida Y, Sankaran S, et al. BRCA1-dependent ubiquitination of gamma-tubulin regulates centrosome number. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(19):8457–8466. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8457-8466.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kote-Jarai Z, Matthews L, Osorio A, et al. Accurate prediction of BRCA1 and BRCA2 heterozygous genotype using expression profiling after induced DNA damage. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(13):3896–3901. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kote-Jarai Z, Salmon A, Mengitsu T, et al. Increased level of chromosomal damage after irradiation of lymphocytes from BRCA1 mutation carriers. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(2):308–310. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernestos B, Nikolaos P, Koulis G, et al. Increased chromosomal radiosensitivity in women carrying BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations assessed with the G2 assay. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(4):1199–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boulton SJ. Cellular functions of the BRCA tumour-suppressor proteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34(Pt 5):633–645. doi: 10.1042/BST0340633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knudson AG. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68(4):820–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeng YM, Cai-Ng S, Li A, et al. Brca1 heterozygous mice have shortened life span and are prone to ovarian tumorigenesis with haploinsufficiency upon ionizing irradiation. Oncogene. 2007;26(42):6160–6166. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kote-Jarai Z, Williams RD, Cattini N, et al. Gene expression profiling after radiation-induced DNA damage is strongly predictive of BRCA1 mutation carrier status. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(3):958–963. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellacosa A, Godwin AK, Peri S, et al. Altered gene expression in morphologically normal epithelial cells from heterozygous carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3(1):48–61. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feilotter HE, Michel C, Uy P, Bathurst L, Davey S. BRCA1 haploinsufficiency leads to altered expression of genes involved in cellular proliferation and development. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salmon AY, Salmon-Divon M, Zahavi T, et al. Determination of molecular markers for BRCA1 and BRCA2 heterozygosity using gene expression profiling. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013;6(2):82–90. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zahavi T, Yahav G, Shimshon Y, et al. Utilizing fluorescent life time imaging microscopy technology for identify carriers of BRCA2 mutation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;480(1):36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barwell J, Pangon L, Georgiou A, et al. Lymphocyte radiosensitivity in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers and implications for breast cancer susceptibility. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(7):1631–1636. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J North Am. 2011;17(1):10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14(4):R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq – a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2014;31(2):166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smyth GK. Limma: linear models for microarray data. In: Gentleman R, Carey VJ, Huber W, Irizarry RA, Dudoit S, editors. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor. New York, NY: Springer; 2005. pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson MD, Oshlack A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2010;11(3):R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Law CW, Chen Y, Shi W, Smyth GK. voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 2014;15(2):R29. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben-Ari Fuchs S, Lieder I, Stelzer G, et al. Geneanalytics: an integrative gene set analysis tool for next generation sequencing, RNAseq and microarray data. Omi A J Integr Biol. 2016;20(3):139–151. doi: 10.1089/omi.2015.0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keen JC, Moore HM. The genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) project: linking clinical data with molecular analysis to advance personalized medicine. J Pers Med. 2015;5(1):22–29. doi: 10.3390/jpm5010022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramsay AJ, Martínez-Trillos A, Jares P, Rodríguez D, Kwarciak A, Quesada V. Next-generation sequencing reveals the secrets of the chronic lymphocytic leukemia genome. Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15(1):3–8. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0922-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Speir ML, Zweig AS, Rosenbloom KR, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D717–D725. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Repana K, Papazisis K, Foukas P, et al. Expression of Syk in invasive breast cancer: correlation to proliferation and invasiveness. Anticancer Res. 26(6C):4949–4954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barr PM, Wei C, Roger J, et al. Syk inhibition with fostamatinib leads to transitional B lymphocyte depletion. Clin Immunol. 2012;142(3):237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fridlich R, Annamalai D, Roy R, Bernheim G, Powell SN. BRCA1 and BRCA2 protect against oxidative DNA damage converted into double-strand breaks during DNA replication. DNA Repair (Amst) 2015;30:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flück M, Zürcher G, Andres AC, Ziemiecki A. Molecular characterization of the murine syk protein tyrosine kinase cDNA, transcripts and protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;213(1):273–281. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vuillaume M-L, Uhrhammer N, Vidal V, et al. Use of gene expression profiles of peripheral blood lymphocytes to distinguish BRCA1 mutation carriers in high risk breast cancer families. Cancer Inform. 2009;7:41–56. doi: 10.4137/cin.s931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao S, Fung-Leung W-P, Bittner A, Ngo K, Liu X. Comparison of RNA-Seq and microarray in transcriptome profiling of activated T cells. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e78644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prakash R, Zhang Y, Feng W, Jasin M. Homologous recombination and human health: the roles of BRCA1, BRCA2, and associated proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7(4):a016600. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coopman PJ, Do MT, Barth M, et al. The Syk tyrosine kinase suppresses malignant growth of human breast cancer cells. Nature. 2000;406(6797):742–747. doi: 10.1038/35021086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coopman PJ, Mueller SC. The Syk tyrosine kinase: a new negative regulator in tumor growth and progression. Cancer Lett. 2006;241(2):159–173. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sonnenblick A, de Azambuja E, Azim HA, Piccart M. An update on PARP inhibitors – moving to the adjuvant setting. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12(1):27–41. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naldi A, Larive RM, Czerwinska U, et al. Reconstruction and signal propagation analysis of the Syk signaling network in breast cancer cells. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(3):e1005432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]