Abstract

This systematic review examined 140 outcome evaluations of primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration. The review had two goals: 1) to describe and assess the breadth, quality, and evolution of evaluation research in this area; and 2) to summarize the best available research evidence for sexual violence prevention practitioners by categorizing programs with regard to their evidence of effectiveness on sexual violence behavioral outcomes in a rigorous evaluation. The majority of sexual violence prevention strategies in the evaluation literature are brief, psycho-educational programs focused on increasing knowledge or changing attitudes, none of which have shown evidence of effectiveness on sexually violent behavior using a rigorous evaluation design. Based on evaluation studies included in the current review, only three primary prevention strategies have demonstrated significant effects on sexually violent behavior in a rigorous outcome evaluation: Safe Dates (Foshee et al., 2004); Shifting Boundaries (building-level intervention only, Taylor, Stein, Woods, Mumford, & Forum, 2011); and funding associated with the 1994 U.S. Violence Against Women Act (VAWA; Boba & Lilley, 2009). The dearth of effective prevention strategies available to date may reflect a lack of fit between the design of many of the existing programs and the principles of effective prevention identified by Nation et al. (2003).

Keywords: Sexual violence, Rape, Perpetration, Primary prevention, Effectiveness evaluation

1. Introduction

Sexual violence2 is a significant public health problem affecting millions of individuals in the United States and around the world (Black et al., 2011; Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, & Lozano, 2002; World Health Organization/London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2010). Efforts to prevent sexual violence before it occurs (i.e., primary prevention) are increasingly recognized as a critical and necessary complement to strategies aimed at preventing re-victimization or recidivism and ameliorating the adverse effects of sexual violence on victims (e.g., Black et al., 2011; Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2004; DeGue, Simon, et al., 2012; Krug et al., 2002). Successful primary prevention efforts, however, require an understanding of what works to prevent sexual violence and implementing effective strategies. Currently, there are no comprehensive, systematic reviews of evaluation research on primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration. Such a review is needed to inform prevention practice and guide additional research to build the evidence base. To address this gap, the current paper provides a systematic review and summary of the existing literature and identifies gaps and future directions for research and practice in the prevention of sexual violence perpetration.

Primary prevention strategies, as defined here, include universal interventions directed at the general population as well as selected interventions aimed at those who may be at increased risk for sexual violence perpetration (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2004). To capture the breadth of possible sexual violence prevention efforts, we defined primary prevention strategies to include any primary prevention efforts, including policies and programs (similar to Saul, Wandersman, et al., 2008). Consistent with the public health approach to sexual violence prevention (Cox, Ortega, Cook-Craig, & Conway, 2010; DeGue, Simon, et al., 2012; McMahon, 2000), strategies to prevent violence perpetration, rather than victimization, are the focus of this review. Although risk reduction approaches that aim to prevent victimization can be important and valuable pieces of the prevention puzzle3, a decrease in the number of actual and potential perpetrators in the population is necessary to achieve measurable reductions in the prevalence of sexual violence (DeGue, Simon, et al., 2012).

1.1. Goals of the current review

1.1.1. Describing the state of the field in sexual violence prevention

The first goal of this review is to describe the broad field of sexual violence prevention research and identify patterns of results associated with evaluation methodology or programmatic elements. Although a number of qualitative reviews, meta-analyses, and one meta-review (e.g., Anderson & Whiston, 2005; Breitenbecher, 2000; Carmody & Carrington, 2000; Vladutiu, Martin, & Macy, 2011) have been conducted over the past two decades, no reviews examine methodological and programmatic elements and sexual violence outcomes across the broad spectrum of sexual violence primary prevention efforts. Several existing reviews focus solely on describing approaches being implemented in the field and the use of underlying theory (Carmody & Carrington, 2000; Fischhoff, Furby, & Morgan, 1987; Paul & Gray, 2011). Two non-systematic reviews identified methodological and programmatic issues associated with sexual violence prevention efforts with college students (Breitenbecher, 2000; Schewe & O’Donohue, 1993) and called attention to the need to measure behavioral outcomes (in addition to changes in attitudes and behavioral intentions) to demonstrate an impact on sexual violence. These reviews also pointed out that the small statistically significant effects reported on the, primarily attitudinal, measures in existing studies may not be truly meaningful (i.e., clinically significant). These existing reviews focused solely on college-based strategies, limiting the generalizability of these findings to community-based and younger audiences.

Three meta-analyses examined the effectiveness of educational prevention programming with college students (Anderson & Whiston, 2005; Brecklin & Forde, 2001; Flores & Hartlaub, 1998), but two of these focused only on attitudinal outcomes (i.e., Brecklin & Forde, 2001; Flores & Hartlaub, 1998). All three reported small to moderate mean effects on attitudes ranging from 0.06 to 0.35 (e.g., rape myth acceptance) and noted that the magnitude of effects decreased as the interval between strategy implementation and data collection increased. In addition, Anderson and Whiston (2005) reported a moderate mean effect size for knowledge (0.57), but reported small mean effect sizes for behavioral intentions (0.14), incidence of sexual violence (0.12), and attitudes considered more distal to sexual violence (0.10; e.g., adversarial sexual beliefs, hostile attitudes toward women), suggesting that the changes may have little clinical significance. Mean effect sizes for rape empathy and indicators of greater rape awareness (e.g., willingness to volunteer at rape crisis centers) were not significantly different from zero. The results from these meta-analyses suggest that knowledge and attitudes are assessed most frequently in prevention programming with college students, with attitudinal measures showing the largest effect sizes in evaluations of those programs. Although attitudes and behaviors are related, attitudes typically account for a relatively small proportion of the variance in behavior (e.g., Glasman & Albarracín, 2006; Kraus, 1995), suggesting that achieving attitude change may not be enough to impact sexual violence behaviors.

The one meta-review (Vladutiu et al., 2011) also focused on reviews of college-based programs. Vladutiu and colleagues noted that reviews often made inconsistent recommendations, primarily due to differences in program context and content and the outcomes examined in the studies. For example, Vladutiu et al. (2011) concluded that longer programs were generally associated with greater effectiveness, but some shorter programs were able to document change when rape myth acceptance was the only outcome of interest. Single-gender audience approaches were generally considered more effective, but primarily when the program focused on attitudes, empathy, and knowledge outcomes related to sexual violence. The meta-review also identified a wide range of content and delivery components that were associated with changes on different outcomes. Finally, Vladutiu et al. (2011) noted that of the reviews included in their meta-review, only one had been published in the last decade (i.e., Anderson & Whiston, 2005). As indicated previously, there are no comprehensive reviews of the sexual violence prevention evaluation literature, and the only systematic reviews have dealt solely with college-based strategies. Relatively few patterns have been identified or recommendations made with respect to improving primary prevention of sexual violence or the rigor of evaluations conducted in the field. An updated, systematic, and comprehensive review of the literature on sexual violence primary prevention programs is warranted.

1.1.2. Summarizing “what works” in sexual violence prevention

The second goal of this review is to identify and summarize the best available evidence on specific sexual violence primary prevention strategies. Prevention practitioners are increasingly being asked to select and implement evidence-based practices and to devote resources toward strategies most likely to have an impact on health outcomes, but guidance and information on navigating this process are lacking (Saul, Duffy, et al., 2008; Tseng, 2012). In particular, we wish to identify effective strategies for preventing sexual violence perpetration behaviors, as that is the ultimate goal of sexual violence prevention efforts. Although targeting risk and protective factors such as attitudes and knowledge are common prevention approaches, the most critical objective is to prevent sexual violence perpetration behaviors and their adverse effects (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2004; World Health Organization/London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2010). Evidence regarding change in sexual violence perpetration behavior, however, is generally absent from the literature (Schewe & O’Donohue, 1993; Vladutiu et al., 2011; World Health Organization/London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2010). By summarizing the evidence on strategies that have been rigorously evaluated for sexually violent behavior, we can identify and categorize programs that currently appear to have evidence of effectiveness, those that are ineffective, and others that are potentially harmful strategies to assist practitioner efforts at better selecting and implementing sexual violence prevention strategies.

2. Method

2.1. Search strategy

To identify studies meeting selection criteria for this review, we first conducted searches of the following online databases between May and August of 2009 and repeated these searches in March and April of 2010 and May of 2012: PsycNet, PsycExtra, PubMed, ERIC, Sociological Abstracts, MEDLINE, Web of Knowledge, Dissertation Abstracts International, and GoogleScholar. Search terms included combinations of the following: (intervention, prevent*, program, effectiveness, efficacy or evaluation) and (perpetration, rape, rapist, sex*, coercion, violence, aggression, assault, offender, or abuse). Second, manual reviews of issues from relevant journals (i.e., Aggression and Violent Behavior, Journal of Adolescent Health, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Journal of Women’s Health, Prevention Science, Psychology of Violence, Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment, Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, Violence Against Women, Violence & Victims) published between January 2008 and May 2012 were also conducted to identify recent work in this area that may not have been cataloged yet in searchable databases. Third, to identify unpublished evaluation reports, solicitations were sent to relevant email lists and e-newsletters, including Prevent Connect, VAWnet, and the Sexual Violence Research Initiative. Fourth, for each article or report identified, we scanned the reference list to identify and retrieve additional reports that might meet inclusion criteria. During each of these iterative search steps, we were over-inclusive to ensure that all abstracts with the potential for inclusion were identified. The initial searches identified more than 10,600 reports, from which 330 were retained for full-text retrieval because they appeared to describe an outcome evaluation of a sexual violence prevention strategy.

2.2. Study selection criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they examined the effectiveness of primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration and were published in print or online between January 19854 and May 2012. Journal articles, book chapters, and reports from government agencies or other institutions were included. Efforts were made to gather unpublished manuscripts, conference presentations, theses, and dissertations (see above). Because the focus on this review is to summarize the evidence base for the primary prevention of sexual violence perpetration, this review did not include studies that exclusively examined secondary and tertiary prevention approaches (e.g., treatment or recidivism prevention), strategies targeting victimization prevention (i.e., risk reduction), or etiological research. In order to avoid double-counting studies, existing reviews and meta-analyses of interventions for sexual violence prevention were excluded.

Only studies that compared one intervention condition to a no-treatment or waitlist control group (i.e., experimental and quasi-experimental designs) or that utilized a single-group pre–post design were included in this review, as the goal was to ascertain changes or differences in the outcomes following exposure to a specific treatment program. Thus, we excluded studies in which data from two different intervention groups were combined and compared to a control group as it was not possible to determine which intervention was responsible for any observed changes on the outcome measures. In addition, we excluded studies in which the intervention and the comparison conditions received different sexual violence prevention programs, because these studies examine the relative benefits of one program compared to another program as opposed to an individual program’s overall effectiveness relative to no intervention. Similarly, studies in which the comparison condition included a combined sample of control participants and participants who received a different sexual violence preventative intervention were also excluded. Because our focus was to examine the effectiveness of strategies to prevent sexual violence, studies that did not measure outcomes relevant to sexual violence perpetration were excluded (see below for a description of the outcomes included).

Of the 330 full-text reports retrieved, 226 reports were excluded. Reports were excluded because they did not describe an outcome evaluation study (45%; n = 101; e.g., review or meta-analysis, program description, theoretical paper, etiological research), did not measure sexual violence-related outcomes (11%; n = 25), evaluated a victimization prevention strategy only (10%; n = 23), did not evaluate a primary prevention strategy (8%; n = 18; e.g., sex offender treatment or recidivism prevention), did not utilize a research design with a comparison group or pre–post measurement (7.5%; n = 17), or met other exclusion criteria (8.1%; n = 27; e.g., non-English language). In addition, we identified several reports that described outcomes from the same study (e.g., a dissertation and a peer-reviewed journal article). In these cases, the peer-reviewed journal article was coded as the primary source and other reports were excluded as a duplicate report (3%; n = 7). In some cases, the excluded reports (e.g., dissertations) were used to provide supplemental information about the sexual violence prevention program or the evaluation design during the coding process. Numerous attempts were made to retrieve all reports identified in the initial searches, including contacting the first author directly and utilizing inter-library loan resources to obtain print copies. However, another eight reports (3.5%) identified through database searches could not be retrieved and were excluded as unavailable. These missing reports were nearly all dissertations and most were published more than 15 years ago; thus, this review may underrepresent these older dissertations.

2.3. Data extraction

2.3.1. Coding process

The review team developed a structured coding sheet5 to extract, quantify, and summarize information from studies. A detailed coding manual was developed to ensure consistency across coders. Before coding began, the review team completed several reviews in order to refine the coding sheet and manual and to increase reliability. The review team consisted of six doctoral-level researchers with expertise in violence prevention. Two reviewers independently coded each of the 104 reports meeting inclusion criteria for this study between November of 2009 and December of 2012. Coding dyads were randomized such that no two coders coded more than one-sixth of the studies together. After each study was coded independently by two reviewers, coding sheets were compared and discrepancies were discussed. Initial agreement by independent coders was acceptable, with reviewers initially agreeing on 75.6% of codes. The coding dyad discussed any items on which there was disagreement until consensus was reached on the best possible response for each item, and the final consensus code was used in analyses.

2.3.2. Study variables and outcomes coded

The variables coded included the report type, study design, sample, nature of the prevention strategy (i.e., setting, delivery, dose, stated program goals, program content), and relevant program outcomes. Study outcomes relevant to sexual violence were coded within eight key categories: sexually violent behavior6 including rates or reports of perpetration or victimization; rape proclivity or self-reported likelihood of future sexual perpetration; attitudes about gender roles, sexual violence, sexual behavior, or bystander intervention; knowledge about sexual violence rates, definitions, and laws; bystanding behavior related to sexual violence, such as intervening in a risky situation or speaking up about violence; bystanding intentions or self-reported likelihood of intervening in a hypothetical scenario; relevant skills related to communication, relationships, or bystanding behavior, and affect/arousal to violence including victim-related empathy and sexual attraction to violence.

The patterns of intervention effects within each study were summarized within and across outcome categories. Intervention effects were considered positive if significant effects were reported on all relevant outcomes in the hypothesized direction at all measurement time points. Study effects were categorized as null if all findings on relevant outcomes were non-significant. Effects were mixed if findings were a combination of positive and null. Studies that had at least one significant finding on any relevant outcome in a negative direction, suggesting potentially harmful effects of the intervention, were categorized as having negative effects. Given the diversity of study designs, outcome measures, and follow-up periods examined, it was necessary to collapse findings from multiple measures and measurement periods within each study to characterize the overall patterns of effectiveness. For example, findings from multiple attitudinal measures relevant to sexual violence were collapsed into a composite “attitudes” category. For some analyses, these findings were further collapsed across outcome types (e.g., attitudes, knowledge) to obtain a summary of the overall effects. Similarly, intervention effects observed at different time points (i.e., post-test, follow-up) were combined into one code to represent the overall pattern of outcomes for that study.

2.3.3. Study sample

Of the 104 reports coded, 73 described a single study in which one prevention strategy was evaluated using a comparison group or pre–post design. The remaining 31 reports described findings from more than one evaluation study. The majority of these reports (n = 25) compared two or more prevention strategies to a single control group, resulting in non-independent data across the various studies. Four reports described two or more separate studies in which samples were distinct and data were independent. Two reports included one study with independent data and two with non-independent data in the same report. To examine outcome data for each separate preventative program or strategy evaluated, we coded information about the study design, program characteristics and content, and outcome data for each of these studies separately. This approach is consistent with the process for systematic reviews recommended by the Task Force on Community Preventive Services (Briss et al., 2000). Thus, the review team identified and coded 140 separate evaluation studies from the 104 reports meeting inclusion criteria. References for all studies included in this review are available in an online supplemental archive (see supplemental materials); studies mentioned in the text are also referenced below.

2.4. Criteria for defining rigorous evaluation designs

Studies were classified as having either a rigorous or non-rigorous evaluation design. Rigorous evaluation designs included experimental studies with random assignment to an intervention or control condition (e.g., randomized controlled trial [RCT], cluster RCT) or rigorous quasi-experimental designs, such as interrupted time series or regression-discontinuity, for strategies where random assignment is not possible due to implementation restrictions (e.g., evaluation of policy). Other quasi-experimental designs (e.g., comparison groups without randomization to condition, including matched groups) and pre–post designs were considered non-rigorous evaluation designs, for the purposes of examining effectiveness in this review, consistent with standards of prevention science and evaluation research (e.g., Eccles, Grimshaw, Campbell, & Ramsay, 2003; Flay et al., 2005; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002).

In addition to design considerations, studies meeting criteria for a rigorous evaluation design were required to have at least one follow-up assessment beyond an immediate post-test assessment. Prior research has established the presence of a rebound effect on attitudinal and knowledge outcomes for sexual violence prevention programs wherein effects are seen immediately after the program but are not evident at longer-term follow-up (Anderson & Whiston, 2005; Brecklin & Forde, 2001; Carmody & Carrington, 2000). In addition, studies without a follow-up assessment often conducted the pre-test and the post-test measurement and the intervention all within the same session, increasing the potential influence of demand characteristics and test–retest effects. Thus, studies that did not include at least one follow-up measurement beyond immediate post-test, regardless of the research design, were also considered to be non-rigorous.

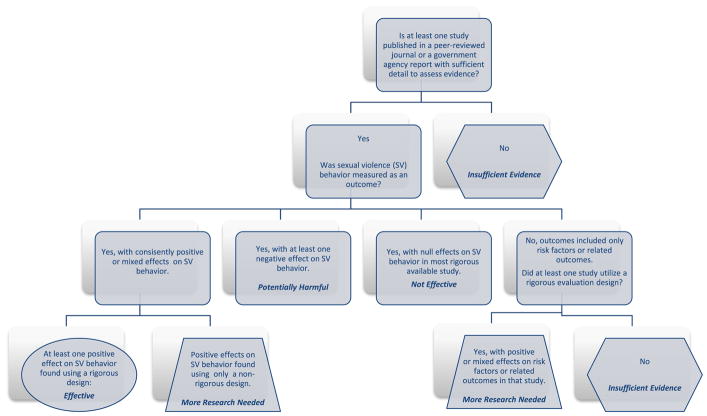

2.5. Criteria for evaluating evidence of effectiveness for preventing sexual violence

To identify prevention strategies with rigorous evidence of effectiveness, we developed criteria to classify specific interventions based on the strength of evidence of effectiveness for preventing sexually violent behavior. These criteria, illustrated in Fig. 1, emphasize sexual violence behavioral outcomes and rigorous experimental research designs that permit inferences about causality. Based on these criteria, interventions were placed into one of five categories: Effective for Sexual Violence Behavioral Outcomes includes those interventions with evidence of any positive impact on sexual violence victimization or perpetration in at least one rigorous evaluation. Interventions categorized as Not Effective for Sexual Violence Behavioral Outcomes were evaluated on sexual violence outcomes using a rigorous evaluation design and had consistently null effects on those measures. Interventions categorized as Potentially Harmful for Sexual Violence Behavioral Outcomes include those with at least one negative effect on sexually violent behavior in a rigorous evaluation. Interventions categorized as More Research Needed included those with evidence of positive effects on sexual violence behavior in a non-rigorous evaluation or positive effects on sexual violence risk factors or related outcomes in a rigorous evaluation. Interventions were considered to have Insufficient Evidence if they were not published in a peer-reviewed journal or formal government report, if they measured outcomes at immediate post-test only without a longer follow-up period, if they found null effects on sexual violence behavioral outcomes using a non-rigorous design; and/or if they only examined risk factors or other related outcomes using a non-rigorous design (regardless of the type of effect).

Fig. 1.

Decision tree for evaluating evidence of effectiveness on sexual violence behavioral outcomes in rigorous evaluation.

We attempted to identify and combine findings from multiple studies or reports examining the same intervention based on the program name or description and used outcomes from the most rigorous evaluation(s) available to categorize the program’s effects. In some cases, researchers may have evaluated modified versions of the same program over time; findings from these evaluations were considered together if the program name did not change and there were no indications that modifications to the structure or content of the program model over time substantially altered the core content or strategy.

3. Results

3.1. Study and intervention characteristics

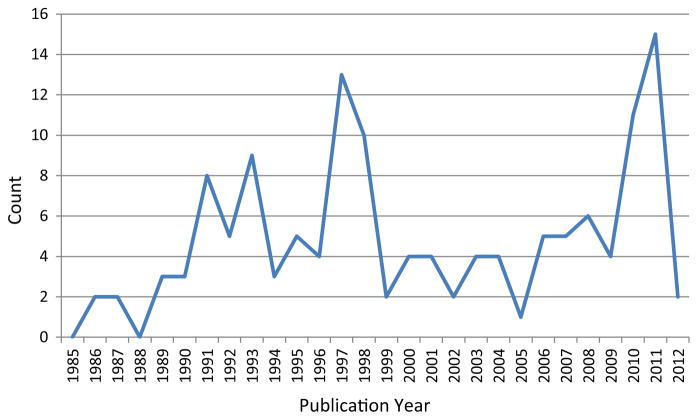

Evaluation of sexual violence perpetration prevention programs peaked in the late 1990s and again in 2010 and 2011 (see Fig. 2). Table 1 describes characteristics of the 140 studies and interventions, including the research design, study population, intervention length, setting, participant and presenter sex, and mode of delivery. Notably, almost two-thirds (n = 84; 60%) of the included studies examined one-session interventions with college populations; these programs had an average length of 68 min. The majority of studies utilizing pre–post designs measured outcomes at immediate post-test only (n = 13, 56.5%). Studies with quasi-experimental designs measured outcomes most often at post-test (n = 12, 34.3%) or with a follow-up period of one month or less (n = 10, 28.6%). In contrast, evaluations using experimental designs had the lowest proportion of studies with post-test only outcomes (n = 19, 23.2%) and the highest proportion with follow-ups at 5 months or longer (n = 17, 20.7%).

Fig. 2.

Number of studies meeting inclusion criteria by publication year (Jan 1985–May 2012).

Table 1.

Study and intervention characteristics.

| Study characteristics (N = 140 studies1) | M (SD) | Range | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication type | ||||

| Peer-reviewed journal article | 96 | 68.6 | ||

| Dissertation | 37 | 26.4 | ||

| Government report | 3 | 2.1 | ||

| Unpublished study | 4 | 2.9 | ||

| Study design | ||||

| Experimental | 82 | 58.6 | ||

| Quasi-experimental | 35 | 25 | ||

| Pre–post | 23 | 16.4 | ||

| Time to last follow-up | ||||

| Immediate post-test | 44 | 32.4 | ||

| 1 month or less | 37 | 27.2 | ||

| 2–4 months | 32 | 23.5 | ||

| 5+ months | 23 | 16.9 | ||

| Study population race/ethnicity | ||||

| >60% White | 84 | 60 | ||

| >60% Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, or Hispanic/Latino | 5 | 3.5 | ||

| Diverse (no group more than 60%) | 19 | 13.7 | ||

| Not reported | 32 | 22.8 | ||

| Study population age 2 | 18.4 (3.9) | 10–47.5 | ||

| Study sample size 3 | 385.4 (560.2) | 22–2643 | ||

| Intervention characteristics | M (SD) | Range | n | % |

|

| ||||

| Number of sessions | 2.6 (3.9) | 1–8 | ||

| One session only | 93 | 72.7 | ||

| 2+ sessions | 35 | 27.3 | ||

| Session length (in min.)4 | 75.6 (61.8) | 10–450 | ||

| Total exposure (sessions × length; in hrs) | 3.7 (7.6) | .2–42 | ||

| 1 h or less | 49 | 49.5 | ||

| More than 1 h | 50 | 50.5 | ||

| Study setting | ||||

| College campus | 98 | 70 | ||

| High school | 20 | 14.3 | ||

| Middle school | 10 | 7.1 | ||

| Elementary school | 3 | 2.1 | ||

| Community | 4 | 2.9 | ||

| Other/mixed settings | 5 | 3.6 | ||

| Participant sex | ||||

| Mixed-sex groups | 82 | 58.6 | ||

| Single-sex group, males only | 40 | 28.6 | ||

| Single-sex groups, males and females | 8 | 5.7 | ||

| Other/not applicable | 10 | 7.1 | ||

| Presenter sex | ||||

| Male and female co-presenters | 35 | 25 | ||

| Male only | 28 | 20.6 | ||

| Female only | 18 | 13.2 | ||

| Other/mixed | 13 | 9.6 | ||

| Unknown/not applicable | 42 | 30.9 | ||

| Presenter type | ||||

| Professional in related field | 35 | 25 | ||

| Peer facilitator | 27 | 19.3 | ||

| Teacher/school staff | 19 | 13.6 | ||

| Advanced student facilitator | 10 | 7.1 | ||

| Other/unknown/not applicable | 49 | 35 | ||

| Program content 5 | ||||

| Attitudes | 117 | 83.6 | ||

| Knowledge | 113 | 80.7 | ||

| Relevant skills | 62 | 44.3 | ||

| Victim empathy | 34 | 24.3 | ||

| Substance use | 29 | 20.7 | ||

| Sexual violence behavior | 19 | 13.6 | ||

| Peer attitudes | 13 | 9.3 | ||

| Social norms related to sexual violence | 11 | 7.9 | ||

| Organizational climate | 5 | 3.6 | ||

| Policy/sanctions | 6 | 4.3 | ||

| Consensual sexual behavior | 4 | 2.9 | ||

| Gender equality | 4 | 2.9 | ||

| Content targeted to specific audience | ||||

| College fraternities | 7 | 5.0 | ||

| Athletic teams | 6 | 4.3 | ||

| Specific racial/ethnic groups | 3 | 2.1 | ||

| Intervention mode(s) of delivery5 | ||||

| Interactive presentation (e.g., with discussion) | 76 | 54.3 | ||

| Didactic-only lectures | 65 | 46.4 | ||

| Film/media presentation | 61 | 43.6 | ||

| Active participation (e.g., role plays, skills practice) | 50 | 35.7 | ||

| Live theater/dramatic performance | 16 | 8.1 | ||

| Written materials | 7 | 5 | ||

| Posters/social norms campaign | 6 | 4.3 | ||

| Community activities/policy development | 3 | 2.1 | ||

Due to missing data (i.e., not available or applicable) for some studies, the total number of included studies does not equal 140 for all categories.

n = 121; mean age was estimated based on grade-level for 34 studies; 19 studies did not report a mean age and it could not be estimated.

Two outliers were not included in the mean: a study evaluating the effects of federal funding allocations resulting from the 1994 Violence Against Women Act on official crime reports included 10,371 jurisdictions (Boba & Lilley, 2009) and a study examining the impact of coordinated community response to intimate partner violence using a telephone survey of 12,039 households (Post, Klevens, Maxwell, Shelley, & Ingram, 2010).

The shortest programs were only 10 min long (Borges, Banyard, & Moynihan, 2008; Nelson & Torgler, 1990) and the longest one-session program was 4.5 h (Beardall, 2008).

Categories are not mutually exclusive.

To examine changes in evaluation methodology over time, we compared studies published in 1999 or earlier (n = 73; 52.1%) to those published in 2000 or later (n = 67; 47.9%). Before 2000, 63% (n = 46) of published studies were RCTs, 30.1% (n = 22) used quasi-experimental designs, and 6.8% (n = 5) used pre–post designs; 28.8% (n = 21) assessed outcomes at immediate post-test only and only 6.8% (n = 5) followed participants for 5 months or longer. Since 2000, 53.7% (n = 36) of published studies were RCTs, 19.4% (n = 13) were quasi-experimental, and 26.9% (n = 18) were pre–post designs; 34.3% (n = 23) of these studies measured outcomes at immediate post-test only, but another 26.9% (n = 18) of studies assessed outcomes after at least 5 months.

3.2. Intervention effects by study characteristics and outcome type

Table 2 summarizes patterns of intervention effects by study characteristic and outcome types. Studies with mixed effects across outcome types and follow-up periods were most common (41.4%; n = 58). More than one-quarter of studies (27.9; n = 39) reported only positive effects and another 21.4% (n = 30) reported only null findings. Nine studies (6.4%) had at least one negative finding suggesting that the intervention was associated with increased reporting of sexually violent behavior (Potter & Moynihan, 2011; Stephens & George, 2009), rape proclivity (Duggan, 1998; Hillenbrand-Gunn, Heppner, Mauch, & Park, 2010), or attitudes toward sexual violence (Echols, 1998; McLeod, 1997; Murphy, 1997). Peer-reviewed studies and government reports tended to have positive or mixed findings more often than dissertations and unpublished manuscripts. Examination of outcomes by study design suggested that evaluations employing more rigorous methodologies (i.e., experimental or quasi-experimental designs with comparison groups) were less likely to identify consistently positive effects than studies using a pre–post design. Similarly, studies that examined outcomes at immediate post-test only were more likely to identify positive effects than studies with a longer follow-up period.

Table 2.

Patterns of intervention effects by study characteristics and outcome type.

| Subset of studies (n) | Type of intervention effect (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Positive | Negative | Mixed | Null | |

| All evaluations (136) | 27.9 | 6.4 | 41.4 | 21.4 |

| Publication type1 | ||||

| Published (95) | 35.8 | 4.2 | 45.3 | 14.7 |

| Unpublished (41) | 12.2 | 12.2 | 36.6 | 39 |

| Study design | ||||

| Experimental design (80) | 23.8 | 6.3 | 48.8 | 21.3 |

| Quasi-experimental (35) | 29.4 | 5.9 | 35.3 | 29.4 |

| Pre–post design (21) | 42.9 | – | 42.9 | 14.3 |

| Time to last follow-up | ||||

| Immediate post-test (43) | 46.5 | – | 39.5 | 14 |

| 1 month or less (37) | 21.6 | 16.2 | 35.1 | 27 |

| 2–4 months | (31) | 19.4 | 3.2 | 48.4 |

| 5+ months (21) | 19 | – | 61.9 | 19 |

| Outcome type2 | ||||

| Sexually violent behavior (21) | 4.8 | 14.3 | 33.3 | 47.6 |

| Rape proclivity (18) | 16.7 | 11.1 | 22.2 | 50 |

| Attitudes (115) | 33 | 3.5 | 33 | 30.4 |

| Knowledge (34) | 61.8 | – | 17.6 | 20.6 |

| Bystanding behavior (10) | 50 | – | 30 | 20 |

| Bystanding intentions (14) | 57.1 | – | 14.3 | 28.6 |

| Relevant skills3 (8) | 62.5 | – | 25 | 12.5 |

| Affect/arousal to violence (9) | 33.3 | – | 33.3 | 33.3 |

Note. Of the 140 studies reviewed, 136 conducted sufficient outcome analyses to determine the effects of the intervention on relevant measures; the remaining four studies from three reports (Feltey, Ainslie, & Geib, 1991; Heppner, Humphrey, Hillenbrand-Gunn, & DeBord, 1995; Wright, 2000) are not included in these analyses.

Published reports included peer-reviewed journal articles and government reports. Unpublished reports included theses or dissertations, unpublished manuscripts, and reports from non-governmental organizations.

Intervention effects by outcome type are not mutually exclusive; most studies included outcome measures in more than one category.

Includes communication, relationship, and bystander intervention skills.

Looking at the pattern of intervention effects by outcome type, results suggest that null effects were more common and positive effects less common on sexually violent behavior and rape proclivity outcomes than on other outcome types. Specifically, about half of all studies measuring sexually violent behavior or rape proclivity found only null effects (47.6%; n = 10); very few studies (4.8%; n = 4) reported only significant, positive effects on these main outcomes of interest. In contrast, the majority of studies measuring knowledge, bystanding behavior or intentions or skills found consistently significant positive effects on these outcomes. No clear pattern was evident for studies assessing attitudinal or affective/arousal outcomes.

To examine the potential impact of intervention length, we estimated the average intervention exposure (i.e., sessions × length) for studies with positive, mixed, negative, and null effects. Findings indicate that interventions with consistently positive effects were about 2 to 3 times longer, with an average length of 6 h (SD = 11.4), than interventions with mixed (M = 3.2 h; SD = 6.6), negative (M = 2.2 h; SD = .9), or null (M = 2.8 h; SD = 4.3) effects.

3.3. Evidence of effectiveness for preventing sexual violence perpetration

As shown in Table 3, only three interventions (based on 3 studies; 2.1%) were categorized as effective for sexual violence behavioral outcomes: Safe Dates (e.g., Foshee et al., 2004, 2005), Shifting Boundaries building-level intervention (Taylor, Stein, Mumford, & Woods, 2013; Taylor et al., 2011), and funding associated with the 1994 U.S. Violence Against Women Act (Boba & Lilley, 2009). Five interventions (based on 11 studies; 6.4%) were found to be not effective for sexual violence behavioral outcomes and three interventions (based on 2 studies; 2.1%) reported evidence suggesting that they were potentially harmful. Another ten interventions (based on 17 studies; 12.1%) were categorized as needing more research in order to understand their effects. Findings within each of these categories are discussed below. The majority of studies reviewed (n = 108; 77.1%) provided insufficient evidence to adequately evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention for preventing sexual violence; these studies were unpublished manuscripts or dissertations which had not been subjected to independent peer review (n = 53; 38%), measured outcomes at immediate post-test only (n = 57; 41%), and/or examined only risk factors or related outcomes for sexual violence using a non-rigorous design (n = 71; 51%). Interventions with insufficient evidence are not included in Table 3 due to the large number of studies in this category and the lack of practical value for this information when the findings are inconclusive.

Table 3.

Summary of the best available evidence for the primary prevention of sexual violence (SV) perpetration.

| Intervention name/citation | Intervention type | Evaluation design/ sample size | Longest follow-up period assessed | Study population | Study notes/limitations | Key outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| SV perpetration/victimization1 | Risk factors/related outcomes2 | ||||||

| Effective for sexual violence behavioral outcomes in a rigorous evaluation | |||||||

| Safe Dates (Foshee et al., 1998, 2000, 2004, 2005) | 10-session curriculum focused on consequences of dating violence, gender stereotyping, conflict management skills, and attributions for violence; student theater production and poster contest; increased services for dating violence victims in community | RCT/14 schools | 4 years | 8th and 9th graders; rural NC county | Reductions in sexual dating violence perpetration and victimization at 4 years later; significant effects found on sexual dating violence perpetration and marginal effects (p = .07) on SV victimization at all four follow-up periods in regression modeling (Foshee et al., 2005) | ||

| Shifting Boundaries, building- level Intervention (Taylor et al., 2011, 2013) | Temporary building-based restraining orders, poster campaign to increase awareness of dating violence, “hotspot” mapping and school staff monitoring over 6–10 week period | RCT/117 classrooms | 6 months | 6th and 7th graders | Reductions in perpetration and victimization of sexual harassment and peer sexual violence; reductions in dating sexual violence victimization but not perpetration | ||

| 1994 Violence Against Women Act funding (Boba & Lilley, 2009) | VAWA funding distributed by U.S. Department of Justice through formula grants and discretionary grant programs to improve criminal enforcement, victim advocacy, and state and local capacity from 1997–2002 | Fixed-effects panel data regression modeling, controlling for crime trends and other related grant funding/10,371 jurisdictions | 1997–2002 | Reports from police jurisdictions | Reduction in annual rape rates (using data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports) | ||

| Not effective for sexual violence behavioral outcomes in a rigorous evaluation | |||||||

| Shifting Boundaries, Classroom- Based Intervention (Taylor et al., 2011, 2013) | 6-session curriculum based on combined content from the Law and Justice and Interaction-Based Treatments evaluated in Taylor, Stein, and Burden (2010a) and Taylor, Stein, and Burden (2010b); focuses on knowledge, relationship boundaries, and bystander intervention | RCT/117 classrooms | 6 months | 6th and 7th graders | No effects on SV perpetration or victimization against peers or partners | ||

| The Men’s Program (Foubert, 2000; Foubert & Marriott, 1997; Foubert & McEwen, 1998; Foubert & Newberry, 2006; Foubert, Newberry, & Tatum, 2007; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Foubert, Brasfield, Hill, & Shelley-Tremblay, 2011) | One hour peer educator-led, victim empathy-based presentation with interactive discussion; some evaluations have assessed variants of the core program with modules focused on specific topics (e.g., consent, bystanding, alcohol) (1 h total) | Multiple designs, including RCT and quasi-experimental | 7 months | Male college students and fraternity members | Although mixed effects on SV behavior were found across studies, effects were consistently null in the most rigorous evaluation using random assignment and analyses by assigned condition (Foubert, 2000; Foubert & McEwen, 1998) | Null effect on SV behavior in an RCT at 7 months follow-up (Foubert, 2000; Foubert & McEwen, 1998); positive effects on SV perpetration in a Solomon 4-group experimental design3 for a subsample of fraternity men with no outcomes reported for non-fraternity men (Foubert et al., 2007) | |

| Acquaintance Rape Prevention Program (Gidycz et al., 2001; Pinzone- Glover, Gidycz, & Jacobs, 1998) | Awareness and education-based program, one-hour session | RCT/1108 | 9 weeks | Male and female college students | Null effects on SV perpetration or victimization | ||

| Coordinated Community Response (CCR) for intimate partner violence (Post et al., 2010) | Federal funding allocated to communities to coordinate prevention and response activities for intimate partner violence (IPV), including: victim services; policy, training, and outreach; efforts to improve enforcement; and primary prevention activities | Controlled QE/12,039 | Challenges in evaluating CCR activities may have limited ability to detect effects; lower rates of any IPV victimization (including SV) in the last year were found in communities with 6-year CCRs vs. 3-year CCRs | Null effects on SV victimization by an intimate partner in CCR vs. control communities | |||

| The Men’s Project (Gidycz, Orchowski, & Berkowitz, 2011) | 1.5 hour workshop and 1 hour booster for men focused on social norms and bystander intervention | RCT/635 | 7 months | College men | Positive short-term (4 month) effects on self-reported SV perpetration were found but these effects were no longer significant at 7 months follow-up | ||

| Potentially harmful for sexual violence behavioral outcomes in a rigorous evaluation | |||||||

| Law and Justice Curriculum (Taylor et al., 2010a,b) | Knowledge-based, 5-session curriculum [precursor of Shifting Boundaries Classroom-Based Intervention; Taylor et al. (2011)] | RCT/123 classrooms | 6 months | 6th and 7th grade students; Cleveland | Authors suggest that iatrogenic findings could be due to increased awareness and reporting in the intervention group | Increased SV perpetration against dating partners at 6 month follow-up | |

| Interaction-based Treatment (Taylor et al., 2010a,b) | 5-session curriculum on setting and communicating relationship boundaries, wanted/unwanted behaviors, bystander intervention [precursor of Shifting Boundaries Classroom-Based Intervention; Taylor et al. (2011)] | RCT/123 classrooms | 6 months | 6th and 7th grade students; Cleveland | Authors suggest that iatrogenic findings could be due to increased awareness and reporting in the intervention group | Decreased peer SV victimization at 6 months; Increased SV perpetration against dating partner at post-test | |

| Videos targeting empathy, attitudes, and education (Stephens & George, 2009) | 50-minute video including the NOMORE Men’s Program (Foubert, 2000) discussing ways for men to help rape victim and including a description of a male police officer’s rape, and a videotaped interview with Jackson Katz regarding the negative intersection of alcohol and rape on college campuses, with introductory preambles by facilitator | RCT/83 | 5 weeks | College men | Marginally significant (p = .053) increase in SV behavior at follow-up for intervention group; significant increase in SV behavior at follow-up for high-risk men in intervention group compared to high-risk men in control group | ||

| More Research Needed | |||||||

| Positive effects on sexual violence behavior in a non-rigorous evaluation or positive effects on risk factors or related outcomes in a rigorous evaluation | |||||||

| Coaching Boys Into Men (Miller et al., 2012a) | Coach-delivered, norms-based dating violence prevention program, 11 brief discussions (10–15 min each) | RCT/16 schools | 3 months | Male high school student athletes | 1-year follow-up data [not included in this review; (Miller et al., 2013)] showed positive effects on dating violence perpetration (combined measure; not SV-specific) | Not measured | Mixed effects on attitudes at 3 months; null effects on dating violence perpetration at 3 months (combined measure of physical, sexual and psychological abuse) |

| Expect Respect — Elementary Version (Meraviglia, Becker, Rosenbluth, Sanchez, & Robertson, 2003; Sanchez et al., 2001) | Bullying and sexual harassment- focused intervention involving a 12-session classroom curriculum (adapted from Bullyproof), staff training, policy development, parent education, and support services | RCT/12 schools (>600 students) | One school year | 5th grade students and school staff | Measurement limitations; focused on bullying outcomes; intervention students and teachers reported witnessing more bullying | Not measured | Improvements in student and staff knowledge of sexual harassment definitions |

| Bringing in the Bystander (Banyard et al., 2007; Moynihan, Banyard, Arnold, Eckstein, & Stapleton, 2010; Potter & Moynihan, 2011) | Bystander education and training program administered as one 90-minute session, three 90-minute sessions, or a 4.5 hour session | Multiple designs, including RCT and quasi-experimental (QE) | 4.5 months | Male and female college students, college athletes, or military personnel | Not measured |

College student samples (1 or

390 min. sessions; RCT design): Positive effects on knowledge, bystander

self-efficacy, and bystander intentions; mixed effects on

attitudes. College athlete sample (one 4.5 hour session; RCT design): Null effects on attitudes and bystander behaviors; positive effects on bystander efficacy and intentions. Military personnel sample (one 4.5 hour session; QE design): Mixed effects on bystander behaviors |

|

| More Research Needed | |||||||

| Positive effects on sexual violence behavior in a non-rigorous evaluation or positive effects on risk factors or related outcomes in a rigorous evaluation | |||||||

| Feminist Rape Education Workshop (Fonow, 1992) | One 25-minute workshop addressing knowledge and rape myths; presented live or on video | RCT/480 | 3 weeks | Male and female college students | Not measured | Positive effects on attitudes | |

| Brief educational video to dissociate sex from violence (Intons-Peterson, Roskos- Ewoldsen, Thomas, Shirley, & Blut, 1989) | 14-minute educational “briefing” video intended to dissociate violence from sexuality viewed prior to exposure to a violent, sexually explicit film | RCT/105 | 2 weeks | College men | Random assignment was used, but groups were not equivalent at pre- test on key outcomes; participants were debriefed about the purpose of the study prior to the follow-up assessment | Not measured | Positive effects on attitudes |

| Campus Rape video (Johansson-Love & Geer, 2003) | 22-minute video featuring interviews with female rape survivors plus educational pamphlet | RCT/151 | 2 weeks | College men | Campus Rape has been evaluated in several additional studies, all with null effects or mixed effects using a non-rigorous design; the preponderance of evidence suggests that this program is likely not effective in changing attitudes over a longer follow-up period (611, 349,449,408,407) | Not measured | Positive effects on one attitudinal measure in one experimental study at 2 week follow-up |

| SHARRP Consent 101 (Borges et al., 2008) | One 10–15 minute session addressing sexual consent | RCT/127 students | 2 weeks | Male and female college students | Small sample size | Not measured | Mixed effects on knowledge and attitudes |

| Acquaintance Rape Education Program (Fay & Medway, 2006) | Two one-hour sessions with activities addressing communication and relationship skills, attitudes, and knowledge | RCT/154 | 5 months | Male and female high school students | More than 50% attrition at 5 month follow-up; n = 75 at follow-up | Not measured | Mixed effects on attitudes |

| Rape Supportive Cognitions (RSC)/Victim Empathy (VE) Videos (Schewe & O’Donohue, 1996) | 50-minute video addressing either knowledge/attitudes or victim empathy; plus brief thought exercise involving a hypothetical rape scenario | RCT/74 | 2 weeks | College men | Small sample size | Not measured | Both video conditions had positive effects on self- reported attraction to sexual aggression; RSC video had positive effects on attitudes; VE video had mixed effects on attitudes |

| Date Rape Education Intervention (Lenihan, 1992) | 50-minute presentation including knowledge-based lecture, video, and a personal experience with date rape with being disclosed by one of the presenters | RCT/821 | 1 month | College men and women | Null effects on three out of four attitudinal measures; no significant changes in attitude scores were observed for male participants | Not measured | Mixed effects on attitudes |

All sexual violence outcomes are based on self-report measures, unless otherwise noted.

Findings for risk factors and related outcomes were only reported here when sexual violence behavioral outcomes were not assessed. However, most studies with sexual violence behavioral outcome measures also included measures of sexual violence risk factors or related outcomes.

Although an experimental design was used in Foubert et al. (2007), this study violated randomization by analyzing and reporting selected subgroup effects only. Thus, it cannot be considered rigorous evidence as defined by this review.

4. Conclusions and discussion

The current systematic review sought to address two key objectives in an effort to inform and advance the research and practice fields of sexual violence primary prevention. First, by examining evaluation research on the primary prevention of sexual violence perpetration over nearly 30 years, we aimed to describe and assess the breadth, quality, and evolution of evaluation research and prevention programming in order to identify gaps for future development, implementation, and evaluation work. Second, we categorized sexual violence prevention programs on their evidence of effectiveness in an effort to inform decision-making in the practice field based on the best available research evidence.

4.1. State of the field: research on the primary prevention of sexual violence perpetration

In the last three decades, a sizable literature has emerged examining the effectiveness of strategies to prevent sexual violence perpetration with more than 100 evaluation reports identified since 1985. The number of studies published in the last two years of this review increased notably, suggesting a possible resurgence of research interest in this area. However, our results suggest that the sexual violence prevention evaluation literature has not seen a steady increase in publications over time to mirror the large increases in other types of sexual violence research. A bibliometric analysis of sexual violence research found that publications with the keywords “rape,” “sexual assault,” or “sexual violence” increased over 250% between 1990 and 2010, from approximately 5990 citations in 1990 to about 15,400 citations in 2010 (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2012). Despite this marked increase in general research attention to sexual violence, the current review suggests that the prevention evaluation literature has remained relatively stagnant both in terms of quantity and quality. In part, this trend may reflect the relatively limited resources available during this period for development and rigorous evaluation of sexual violence primary prevention approaches (Jordan, 2009; Koss, 2005). Fortunately, funding for sexual violence evaluation research has increased over the last decade. For example, CDC funded 27 research projects with a focus on sexual violence between 2000 and 2010, resulting in the increased availability of more than $19 million in federal funding for the field; more than half of these projects involved prevention evaluation research (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2012; DeGue, Simon, et al., 2012). Although this funding represents a large proportional increase in federal dollars available for sexual violence research, the total research funding available remains low compared to other forms of violence and other areas of public health (Backes, 2013; DeGue, Massetti, et al., 2012).

In addition to limiting the quantity of evaluation research studies, fiscal constraints may have also resulted in less rigorous research designs, as large randomized controlled trials of prevention strategies are generally considered costly to implement. Indeed, this review found two-thirds of the evaluation studies conducted over nearly 30 years examined brief, one-session interventions with college populations, approaches that are relatively inexpensive to implement and evaluate. In terms of measurement, few of these studies (n = 11) measured sexually violent behavior, and none found consistently positive effects on these key behavioral outcomes. Of course, the predominance of brief awareness and education strategies in the literature not only reflects resource limitations for research but also implementation challenges in the field. Many colleges may limit access to students to only one class period or have policies requiring only 1 h of relevant training—spurring the development of programs to fit this need. Nevertheless, future research is needed that rigorously evaluates a more diverse and comprehensive set of prevention approaches with various populations.

Although the vast majority of preventative interventions evaluated to date have failed to demonstrate sufficient evidence of impact on sexual violence perpetration behaviors, progress is being made. Findings from several large, federally-funded7 effectiveness trials of comprehensive, multi-component primary prevention strategies have been published more recently, with interventions targeting a broader, and younger, segment of the population (e.g., Foshee et al., 2004, 2012; Miller et al., 2012b; Taylor et al., 2013) with additional evaluations underway (e.g., Cook-Craig et al., in press; Espelage, Low, Polanin, & Brown, 2013; Tharp, Burton, et al., 2011). This new research is providing the primary prevention practice field with additional evidence on which to base decisions about resource allocation and implementation in order to prevent sexual violence. However, as we discuss below, more rigorous evaluation research on various prevention approaches is needed before we can expect to see measurable reductions in sexual violence at the population level.

4.1.1. Evaluation methodology

A movement toward evidence-based policymaking has been gaining traction in the US. In 2012, the U.S. Office of Management and Budget directed federal agencies to prioritize rigorous research evidence in budget, management, and policy decisions in order to improve effectiveness and reduce costs (Office of Management & Budget, 2012). These shifting federal priorities reflect a growing push in the field by researchers and advocacy organizations such as the Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy (www.coalition4evidence.org) for increased investment in evaluation research and the implementation of evidence-based programs. Evaluation guidelines provided by these various stakeholders emphasize the value of well-conducted, rigorous evaluations with an emphasis on randomized controlled trials to permit the strongest possible conclusions regarding causality (e.g., Flay et al., 2005; Office of Management & Budget, 2012).

A small majority (58.6%) of the studies in this review utilized an experimental design with randomization, and about three-quarters of these collected follow-up data beyond an immediate post-test. Thus, fewer than half (45%; n = 63) of the included studies met our minimum criteria for a rigorous evaluation. Further, only 17 of the rigorous evaluations included measures of sexually violent behavior, the intended public health outcome of the programs. In summary, after nearly 30 years of research, the field has produced very few evaluation studies using a research design that, if well-conducted, would permit conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the intervention for preventing sexually violent behavior. This shortage of rigorous research accounts, in large part, for the lack of evidence-based interventions available to practitioners to date.

The use of less rigorous methodologies, such as single-group or quasi-experimental designs, is often necessary and cost-effective for the purposes of program development, improvement, and to establish initial empirical support for an intervention (Tharp, DeGue, et al., 2011). However, there is an implicit expectation that the rigor of evaluation research will continue to increase over time, both for individual interventions with promising initial outcomes and for the literature as a whole (Tharp, DeGue, et al., 2011). However, this review did not find evidence of a general shift toward more rigorous evaluation methodology in the field over time. A comparison of studies published before and after 2000 found that evaluations completed from 2000 to 2012 were actually less likely to utilize an experimental design with randomization (53.7% vs. 63%) and more likely to utilize a pre–post design (26.9% vs. 6.8%) than studies from 1985 to 1999. Further, most of the identified interventions were the subject of a single evaluation rather than an evolving program of research, regardless of the initial study quality or findings. Progress in the field is dependent on systematic research initiatives that build off of the existing evidence base and move toward the ultimate goal of identifying “what works”.

4.1.2. Prevention approach

Much has been learned from the prevention science and public health fields about the characteristics of effective prevention strategies. For example, Nation et al. (2003) identified nine “principles of prevention” that were strongly associated with positive effects across multiple literatures and found that effective interventions had the following characteristics: (a) comprehensive, (b) appropriately timed, (c) utilized varied teaching methods, (d) had sufficient dosage, (e) were administered by well-trained staff, (f) provided opportunities for positive relationships, (g) were socio-culturally relevant, (h) were theory-driven, and (i) included outcome evaluation. Similar sets of “best practices” for prevention have been articulated elsewhere (e.g., Small, Cooney, & O’Connor, 2009). With the exception of outcome evaluation which we addressed above, we consider how well the sexual violence literature to date aligns with each of these principles.

4.1.2.1. Comprehensive

Comprehensive strategies should include multiple intervention components and affect multiple settings to address a range of risk and protective factors for sexual violence (Nation et al., 2003). However, the vast majority of interventions evaluated for sexual violence prevention have been fairly one-dimensional — implemented in a single setting, typically a school or college, and often utilizing a narrow set of strategies to address individual attitudes and knowledge related to sexual violence. A minority of programs included content to address individual-level risk factors other than attitudes and knowledge (e.g., relevant skills and behaviors). Fewer than 10% included content to address factors beyond the individual level, such as peer attitudes, social norms, or organizational climate and policies, despite evidence that relationship and contextual factors are also important in shaping risk for sexual violence perpetration (Casey & Lindhorst, 2009; Tharp et al., 2013). Several relatively recent studies have evaluated interventions that utilize a more comprehensive approach by combining educational or skills-building curricula with social norms campaigns, policy changes, community interventions, and/or environmental changes (e.g., Ball et al., 2012; Foshee et al., 2004; Taylor et al., 2011); however, comprehensive interventions remain the exception and not the norm. In order to potentially reduce and prevent sexual violence, program developers should build off of this work and develop a range of comprehensive strategies geared toward multiple populations.

4.1.2.2. Appropriately-timed

More than two-thirds of sexual violence prevention strategies evaluated thus far have targeted college samples. There is consensus that college men and women are at a particularly high risk for sexual violence perpetration and victimization, making this a key population for intervention. However, because many college men have already engaged in sexual violence before arriving on campus or will shortly thereafter (Abbey & McAuslan, 2004), prevention initiatives that address this age group may miss the window of opportunity to prevent sexual violence before it starts. Primary prevention efforts may be best targeted at younger populations—before college. Sexually violent behavior is often initiated in adolescence (Abbey & McAuslan, 2004), and more than 40% of victims will experience their first completed rape before age 17 (Black et al., 2011). Only about one-quarter of the studies reviewed here evaluated interventions in high schools, middle schools, or elementary schools. However, younger populations are getting increased attention from program developers and evaluators in recent years. One-third of the evaluations involving school-aged youth in this review were published in 2010 or later, and several randomized trials of school-based strategies are underway in the field (Cook-Craig et al., in press; Espelage et al., 2013; Tharp, Burton, et al., 2011). It is notable that the only strategies with evidence of effectiveness on sexually violent behavior, to date, target adolescents. This is consistent with findings from a recent review of intimate partner violence prevention strategies (Whitaker, Murphy, Eckhardt, Hodges, & Cowart, 2013), suggesting that adolescence may represent a critical window to intervene on these related behaviors. Better targeting our prevention strategies to adolescents and evaluating these efforts into the college years will aid in our understanding about the preventative effects of these interventions.

4.1.2.3. Varied teaching methods

Research indicates that preventative interventions are most successful when they include interactive instruction and opportunities for active, skills-based learning (Nation et al., 2003). Prior reviews of sexual violence prevention programs also suggest that engaging participants in multiple ways (e.g., writing exercises, role plays) and with greater participation may be associated with more positive outcomes (Paul & Gray, 2011). In the current review, nearly one-third of interventions utilized a single mode of intervention delivery (or teaching method) and another 40% utilized two modes of instruction. The most common modes of intervention delivery involved interactive presentations (i.e., presentations with opportunities for questions or discussion), didactic-only lectures, and/or videos. Only about one-third of the programs involved active participation in the form of role playing, skills practice, or other group activities. The effectiveness of program development efforts may be increased by focusing on integrating more active learning methods in order to increase the likelihood that participants acquire and retain skills and knowledge.

4.1.2.4. Sufficient dose

Prevention approaches must provide a sufficient “dose” of the intervention, as measured by total exposure to program content or contact hours, to have an effect on the behavior of participants (Small et al., 2009). The intensity needed to be effective will vary by the type of approach, the needs and risk level of participants, and the nature of the targeted behavior, but longer programs may be more likely to achieve lasting results (Nation et al., 2003). Our findings suggest that the dose received by participants is often small. Three-quarters of interventions had only one session, and half of all studies involved a total exposure of 1 h or less. While it may be possible to impact some behaviors with a brief, one-session strategy, it is likely that behaviors as complex as sexual violence will require a higher dosage to change behavior and have lasting effects. Indeed, we found that interventions with consistently positive effects in this review tended to be 2 to 3 times longer, on average, than interventions with null, negative, or mixed effects. Of course, there are practical limitations on the time and resources available to implement prevention strategies in most settings. The most efficient interventions would balance the necessity of providing a sufficient dose to achieve intended outcomes with the need for long-term sustainability and scalability. But, outcomes are critical: No matter how brief or low-cost an intervention may be, if it does not impact the outcomes of interest, implementation will not be an efficient or effective use of resources.

4.1.2.5. Fosters positive relationships

Strategies that foster positive relationships between participants and their parents, peers, or other adults have been associated with better outcomes in past prevention research (Nation et al., 2003). Although the short length and didactic nature of most interventions reviewed here do not lend themselves well to relationship-building, strategies that work to nurture or capitalize on positive relationships are beginning to gain traction in the field. For example, programs that engage youth in facilitated peer support groups (e.g., Expect Respect; Ball et al., 2012) can leverage positive peer influences to reduce violent behavior. Further, strategies that train and empower youth to serve as active bystanders (e.g., Bringing in the Bystander; Banyard, Moynihan, & Plante, 2007; or, Green Dot; Cook-Craig et al., in press) utilize existing peer networks to diffuse positive social norms and messages about dating and sexual violence. In addition, recent work to involve parents in dating violence prevention is a promising new direction (see for example, Families for Safe Dates; Fo et al., 2012). Although these particular interventions have not yet demonstrated effects on sexual violence perpetration in a rigorous evaluation, research is ongoing, and the attention to the role of relationships in behavior modification and risk may prove fruitful.

4.1.2.6. Sociocultural relevance

Prevention programs that are sensitive to and reflective of community norms and cultural beliefs may be more successful in recruitment, retention, and achieving outcomes (Nation et al., 2003; Small et al., 2009). Only three interventions were identified that included content designed for specific racial/ethnic groups, including Asian-Pacific Islander (Stephens, 2008), African-American (Weisz & Black, 2001) and Latino/a (Nelson et al., 2010) populations. Fourteen studies (10% of the total) evaluated programs targeting fraternity men, male athletes, or members of the military. No studies evaluated programs targeting sexual minority populations. Overall, about two-thirds of the interventions reviewed were implemented with majority-White samples. Nation et al. (2003) note that involving members of the target population in the development and implementation of prevention strategies may improve the programs’ perceived relevance to the community’s needs. Future program development and evaluation research efforts should gauge the extent to which interventions with culturally specific approaches result in increased cultural relevance, recruitment, retention, and impact on preventing sexual violence.

4.1.2.7. Well-trained staff

Effective programs tend to have staff or implementers that are stable, committed, competent, and can connect effectively with participants (Mihalic, Irwin, Fagan, Ballard, & Elliott, 2004). Sufficient “buy-in” to the program model is also important to credibly deliver and reinforce program messages (Nation et al., 2003). Although researchers are increasingly recognizing the importance of measuring and describing characteristics of implementers and training procedures, few reports included this information. Reports were typically limited to a basic description of the type of implementer (e.g., peer, school staff, professional). About one-quarter of the interventions were implemented by professionals with expertise related to sexual violence prevention and extensive knowledge of the program model (e.g., program developers, sexual violence prevention practitioners). The majority of programs were implemented by peer facilitators, advanced students, or school/agency staff who may not have specific expertise in the topic. The sexual violence prevention field would benefit from more extensive descriptions of program staff and training and implementation research to determine characteristics of program staff that may enhance the preventative effects of our programs.

4.1.2.8. Theory-driven

A recent review by Paul and Gray (2011) concluded that sexual violence prevention strategies often lack a strong theoretical framework and fail to utilize established social psychological and behavior change research to inform program development. Etiological theories that identify modifiable points for intervention in the development of health risk behaviors are extremely valuable as a basis for prevention development (Nation et al., 2003), especially when supported by evidence that the factors identified represent causal influences in a theoretical model. Although we did not systematically examine the theoretical underpinnings of interventions, attention to etiological theory (e.g., risk and protective factors and processes; Nation et al., 2003) was implicit in many studies with a focus on changing presumed sexual violence risk factors. The most common risk factors addressed were knowledge and attitudes about rape, women, and sex. There is limited empirical evidence linking legal or sexual knowledge to sexual violence perpetration (Tharp, DeGue, et al., 2011) and virtually no theoretical reason to believe that rape is caused by a lack of awareness about laws prohibiting it. However, education about rape laws and statistics remains a frequent component of sexual violence prevention strategies. Attitudes are similarly attractive targets for intervention because they are relatively easy to measure and assess for change in the short-term. However, more empirical and theoretical work is needed to establish these factors as functional pieces in violence development rather than merely correlates or indicators and to provide well-developed, integrative theories to explain the role of attitudes and their potential value as primary prevention targets. On the other hand, cognitive factors, including hostility toward women, traditional gender role adherence, and hypermasculinity, have shown consistent links to sexual violence perpetration (Tharp et al., 2013) but are rarely addressed directly in prevention programs. Strategies that involve working with young men to shape and support healthy views of masculinity and relationships, such as Men Can Stop Rape (www.mencanstoprape.org) or Coaching Boys into Men (Miller et al., 2012b), are promising exceptions, but more evaluation research is needed in order to ascertain whether these programs have an impact on sexual violence.

4.2. What works (and what doesn’t) to prevent sexual violence perpetration?

Emphasizing rigorous evaluation and behavioral outcomes, we developed and applied a set of criteria to identify specific interventions with more or less evidence of effectiveness for the primary prevention of sexual violence perpetration in order to serve as a guide for decision-making. Communities and organizations are increasingly interested in and required to implement evidence-based interventions with an expectation of achieving reductions in sexual violence. Table 3 is intended to serve as a resource and tool for this purpose. Although we believe that this approach has many practical advantages, it has notable limitations as well. Most importantly, it is limited by the ever-growing and evolving nature of the evaluation research literature. Over time, additional effective interventions will be identified, some will be found to be ineffective, and others will find that their effects can be replicated—or not—in different populations. The current review provides only a snapshot of knowledge regarding “what works” currently to prevent sexual violence. Practitioners are encouraged to consider this information in the context of the needs, goals, and resources of their organization and to supplement this summary with additional information about the strategy and new research findings as they become available. This summary may also be useful in identifying promising strategies in need of further research or when developing new comprehensive strategies that combine the strengths of multiple evidence-based approaches. Future research investments should reflect the best available science and theory, and move beyond approaches that have proven ineffective or insufficient.

4.2.1. What works (so far)?

Only three strategies, to date, have evidence of at least one positive effect on sexual violence perpetration behavior using a rigorous, controlled evaluation design. The best available evidence suggests that these strategies, if well-implemented with an appropriate population, may be effective in preventing sexually violent behavior. Notably, none of these evaluations have been replicated and it is not known whether their effects will generalize to other populations, age groups, or to forms of sexual violence that were not assessed. In addition, it is likely that none of these approaches, in isolation, will be sufficient to reduce rates of sexual violence at the population-level, even if brought “to scale” (Dodge, 2009). Instead such approaches should be viewed as potential components of an evidence-based, comprehensive, multi-level strategy to combat sexual violence.

Safe Dates is a universal dating violence prevention program for middle- and high-school students involving a 10-session curriculum addressing attitudes, social norms, and healthy relationship skills, a 45-minute student play about dating violence, and a poster contest. Results from one rigorous evaluation using an RCT design showed that four years after receiving the program, students in the intervention group were significantly less likely to be victims or perpetrators of self-reported sexual violence involving a dating partner relative to students in the control group (Foshee et al., 2004).

Shifting Boundaries is a universal, school-based dating violence prevention program for middle school students with two components: a 6-session classroom-based curriculum and a building-level intervention addressing policy and safety concerns in schools. Results from one rigorous evaluation indicated that the building-level intervention, but not the curriculum alone, was effective in reducing self-reported perpetration and victimization of sexual harassment and peer sexual violence, as well as sexual violence victimization (but not perpetration) by a dating partner (Taylor et al., 2011, 2013).

The U.S. Violence Against Women Act of 1994 (VAWA) aimed to increase the prosecution and penalties associated with sexual assault, stalking, intimate partner violence and other forms of violence against women, as well as to fund research, education and awareness programs, prevention activities, and victim services (Boba & Lilley, 2009). Results of a rigorous, controlled quasi-experimental evaluation suggest that VAWA-related grant funding through the U.S. Department of Justice for criminal justice-related activities was associated with a .066% annual reduction in rapes reported to the police, as well as reductions in aggravated assault. Given the deficit of policy, environmental, or community-level change strategies with empirical, or even theoretical, evidence in this field (DeGue, Holt, et al., 2012), communities and researchers may be able to learn from the programs and strategies funded by VAWA to inform development or implementation of similar approaches to prevent sexual violence.

4.2.2. What (probably) doesn’t work, or might be harmful?

This review identified five interventions with evidence of null effects on sexually violent behavior in at least one rigorous evaluation. It is notable that most of these programs have shown positive effects on other related outcomes, including potential risk factors or moderators. In some cases, positive effects on behavioral outcomes were identified using non-rigorous evaluation designs. Additional research that evaluates these strategies with different measures of sexual violence perpetration, stronger implementation, different populations, longer follow-up periods, or larger sample sizes may possibly reveal positive effects on behavior. However, the most rigorous evidence currently available suggests that these strategies have so far not been effective in changing rates of sexual violence perpetration after a reasonable follow-up period.