Abstract

Objective

Screening for diabetes in low-resource countries is a growing challenge, necessitating tests that are resource and context appropriate. The aim of this study was to determine the diagnostic accuracy of a self-administered urine glucose test strip compared with alternative diabetes screening tools in a low-resource setting of Cambodia.

Design

Prospective cross-sectional study.

Setting

Members of the Borey Santepheap Community in Cambodia (Phnom Penh Municipality, District Dangkao, Commune Chom Chao).

Participants

All households on randomly selected streets were invited to participate, and adults at least 18 years of age living in the study area were eligible for inclusion.

Outcomes

The accuracy of self-administered urine glucose test strip positivity, Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)>6.5% and capillary fasting blood glucose (cFBG) measurement ≥126 mg/dL were assessed against a composite reference standard of cFBGmeasurement ≥200 mg/dL or venous blood glucose 2 hours after oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) ≥200 mg/dL.

Results

Of the 1289 participants, 234 (18%) had diabetes based on either cFBG measurement (74, 32%) or the OGTT (160, 68%). The urine glucose test strip was 14% sensitive and 99% specific and failed to identify 201 individuals with diabetes while falsely identifying 7 without diabetes. Those missed by the urine glucose test strip had lower venous fasting blood glucose, lower venous blood glucose 2 hours after OGTT and lower HbA1c compared with those correctly diagnosed.

Conclusions

Low cost, easy to use diabetes tools are essential for low-resource communities with minimal infrastructure. While the urine glucose test strip may identify persons with diabetes that might otherwise go undiagnosed in these settings, its poor sensitivity cannot be ignored. The massive burden of diabetes in low-resource settings demands improvements in test technologies.

Keywords: diabetes, low-resource settings, diagnostics, urine glucose test strip, screening

Strengths and limitations of the study.

This is one of the first studies to determine the prevalence of diabetes and report on the screening accuracy of urine glucose test strips in Cambodia, which are commonly used as screening tests in this setting.

We used a prospective community-based design and had a large sample size with high participation rate, though participation bias towards those able to miss a day of work to attend a clinic visit may still have been an issue.

The use of a composite reference test and not evaluating those with capillary fasting blood glucose >200 mg/dL by the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) could have affected our study results, though the use of OGTT allows comparison of our results with those in a number of other studies.

The urine glucose test was self-administered and self-reported, which is pragmatic and aligns with the practices at MoPoTyso and other clinical settings in Cambodia; however, errors in interpreting the test result could influence accuracy.

Background

According to the International Diabetes Federation, 415 million adults are living with diabetes globally, almost half of whom are undiagnosed, and this number is expected to increase to 642 million by 2040.1 As is the case for most non-communicable diseases, three quarters of those affected live in low-income and middle-income countries. In Cambodia, for example, there are an estimated 230 000 people with diabetes, who are at risk for the associated microvascular and macrovascular complications of this disease, including cardiovascular disease.1 2 Strategies to reduce cardiovascular disease risk may also prevent and control diabetes, which would further reduce rates of eye, kidney and neural damage due to diabetes complications.3 To facilitate screening and monitoring for diabetes in these low-income and middle-income countries, a low-cost, point-of-care diagnostic test that is resource and context appropriate is needed.

In low-resource settings, urine glucose test strips have been used as diabetes screening tools because they are inexpensive, non-invasive and easy to use.4 5 While these tests do not require fasting and are user friendly, they can only detect glucose after it has exceeded the threshold for reabsorption by the kidneys and appears in the urine. The reported threshold varies and is affected by kidney function.6 Although their low sensitivity makes them inadequate for use as a screening tool,7–9 the WHO acknowledges that they may have a place in low-resource settings where other tests are not possible and the prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes may be high.9 Currently, many people are not diagnosed until severe complications develop. Although the sensitivity of the urine test delays diagnosis relative to other methods, it may provide an opportunity to reduce further advancement of complications.

MoPoTsyo, a non-governmental organisation, provides screening and care services to people with diabetes and hypertension in Cambodia through an innovative, community-based peer educator model.10–12 MoPoTsyo uses urine glucose test strips issued in the community and self-administered by patients as the initial method of diabetes screening, which has allowed them to screen over 700 000 adults, followed by confirmation with blood glucose testing for those who have a positive urine test. The aim of this study was to determine the diagnostic accuracy of a self-administered urine glucose test strip compared with alternative diabetes screening tools in a low-resource setting of Cambodia. We also explored whether individuals with diabetes who were detected by urine glucose test strips differed in health status compared with those who were missed by this test but detected by blood glucose measurement. Greater understanding of the performance of this test by the MoPoTsyo programme will help to inform its optimal use.

Methods

Study design and procedures

A prospective cross-sectional study was performed among members of the Borey Santepheap Community in Cambodia (Phnom Penh Municipality, District Dangkao, Commune Chom Chao) from November 2013 to October 2014. All households on randomly selected streets were invited to participate by a local peer educator, who described the study to all potential household members. Adults at least 18 years of age living in the study area were eligible for inclusion. Individuals were excluded if they had diabetes or hypertension or had taken medications for diabetes and/or high blood pressure in the last 30 days, had kidney disease or had received dialysis. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Study methods and results are reported in alignment with the 2015 standards for reporting diagnostic accuracy (STARD) recommendations.13

After enrolment, all participants were screened for diabetes using a self-administered and self-reported urine glucose test strip (Sichuan Medicines and Health Products, Chengdu, China). Participants were taught how to use the test strip and read the results with assistance of a colour chart and were given several ways to report results to their peer educator. All participants were then invited to attend the clinic following an 8-hour fast for laboratory-confirmed tests for diabetes and associated comorbid risk factors. Upon arriving at the clinic, all participants provided a urine sample, a venous blood sample and a finger stick blood sample for capillary fasting blood glucose (cFBG) measurement (On Call Plus Glucometer, Acon Laboratories, San Diego, USA, https://www.aconlabs.com/us/glucose/on-call/plus-bgms/). If the cFBG was less than 200 mg/dL, they were asked to consume a 75 g oral glucose load for the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). The oral glucose load was ingested within 5 min of starting consumption, and 2 hours after ingestion, further venous blood and finger stick blood samples were obtained for glucose measurements. During the visit, a health history was completed based on the WHO STEPSSurveillance Questionnaire14 and blood pressure measured by trained clinical staff using an electronic device (Omron Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). All devices used in the study were owned and used previously by MoPoTsyo within the guidelines of the Cambodian Ministry of Health; none of the devices were investigational. Additional laboratory tests performed included HbA1c (DCA Vantage Analyzer, Siemens AG, Germany), serum creatinine, glucose, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides (Humalyzer 3000 Chemistry Analyzer, Human Diagnostics, Germany) and spot urine creatinine, protein and albumin tests (Combilyzer Dipstick Reader, Human Diagnostics, Germany).

A sample size of 1315 participants was calculated for a desired precision range of 10% and an estimated sensitivity and specificity of the urine glucose test strip of 21% and 90%, respectively, which is also sufficient for analysis of HbA1c, OGTT and FBG as the test strip has the lowest performance. The sample size for the study was calculated based on Buderer’s formula,15 accounting for a 3% dropout rate and a 5% national prevalence of diabetes.16

Data analysis

The index tests of interest were a positive self-administered urine glucose test strip, HbA1c>6.5% and cFBG ≥126 mg/dL. Diagnostic accuracy was assessed against a composite reference standard, which was cFBG ≥200 mg/dL, or venous blood glucose, 2 hours after OGTT ≥200 mg/dL.17 18 If the participant’s cFBG was >200 mg/dL, the patient was considered to have diabetes and an OGTT was not performed. Other measures were defined as follows: overweight (body mass index (BMI) ≥25 or waist circumference >90 cm for men or >80 cm for women19), elevated blood pressure (systolic pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic pressure ≥90 mm Hg), albuminuria (≥20 mg/L) and elevated albumin/creatinine ratio (≥30 mg/g). We calculated sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio (LR+) and negative LR (LR–), with 95% CIs.

Subgroup analyses were not prespecified, and therefore used to explore the performance of the urine glucose test strip in participants at increased risk for diabetes mellitus, including age (≥50 years), BMI (≥25), gender and waist circumference (>90 cm for men or >80 cm for women). Logistic regression analyses were also used to determine if the diagnostic accuracy of the index test was impacted by these clinical features. Prevalence of diabetes by subgroup was compared by Χ2 test. We also explored whether the individuals correctly classified by the urine glucose test strip had better or worse controlled diabetes than those misclassified by the test, as defined by various clinical and laboratory measures. Mean values of continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test, while proportions of dichotomous values were compared using the Χ2 test. Data were analysed using Stata/SE 13.1 (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA).

Results

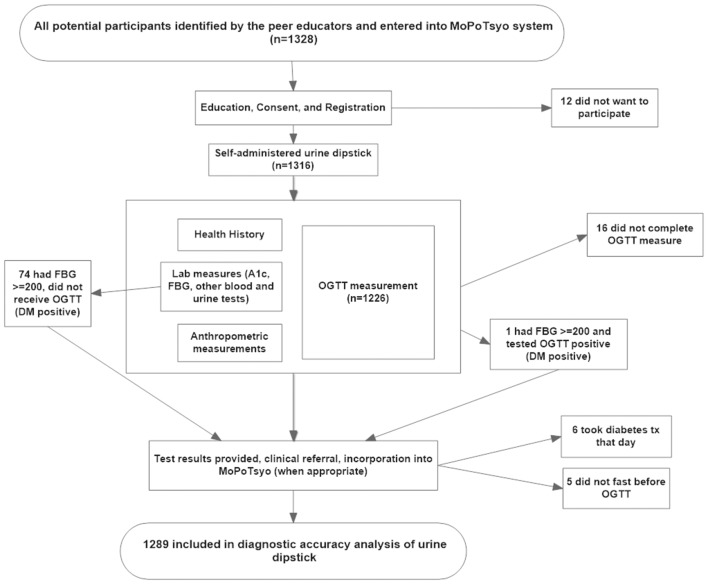

Of 1328 eligible study subjects, 1316 participated in the study and 1289 were included in the analysis (figure 1). Participants were excluded from the analysis if they did not complete the OGTT due to vomiting or other reasons (16), were not fasting prior to the clinic visit (5) or reported taking medication for diabetes that day (6). Of the analysed participants, 75% (972/1289) were women, mean age was 51 years, 31% had high BMI and 13% had elevated blood pressure, although only 8% were taking antihypertensive medications. Characteristics of the participants included in the analysis are presented in table 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. DM, diabetes mellitus; FBG, fasting blood glucose; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included participants

| Mean (SD) or % n=1289 | |

| Age (years) | 51.4 (14.9) |

| Female (%) | 75.4 |

| BMI* | 23.2 (4.1) |

| High BMI (%) | 30.5 |

| Waist circumference above cut-off (%)† | 46.1 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 123.5 (20.6) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 80.8 (12.1) |

| Elevated blood pressure (%) | 12.9 |

| Take treatment for high blood pressure (%) | 8.2 |

A total of 234 individuals had diabetes based on the composite reference standard of either cFBG (70, 30%) or OGTT (164, 70%), corresponding to a prevalence of 18%. The 70 individuals with cFBG ≥200 mg/dL also all had HbA1c measurements >6.5%. Of the index tests evaluated, the urine glucose test strip had lower sensitivity (14.1%, 95% CI: 9.90 to 19.2) than cFBG (73.9%, 95% CI: 67.8 to 79.4) and HbA1c (75.2%, 95% CI: 69.2 to 80.6). All three tests offered high specificity (99.3%, 95% CI: 98.6 to 99.7; 96.8%, 95% CI: 95.5 to 97.8 and 98.5%, 95% CI: 97.5 to 99.1, respectively) (table 2). The urine glucose test strip failed to identify 201 individuals with diabetes (false negatives) and falsely identified seven participants without diabetes (false positives). The 201 patients with diabetes who were not identified by the urine test had significantly lower venous FBG, lower 2-hour OGTT and lower HbA1c compared with those correctly diagnosed, but were similar in other characteristics (table 3). The seven false positive individuals had higher HbA1c, higher systolic blood pressure and higher proportion receiving treatment for hypertension than those with true negative results (table 3).

Table 2.

Diagnostic accuracy of urine glucose test strip, capillary fasting glucose and HbA1c determined by comparison with the composite reference standard (n=1289)*

| Urine glucose test strip positive | cFBG≥126 mg/dL | HbA1c>6.5% | |

| True positive (n) | 33 | 173 | 176 |

| False positive (n) | 7 | 34 | 16 |

| False negative (n) | 201 | 61 | 58 |

| True negative (n) | 1048 | 1021 | 1039 |

| True diabetes prevalence† (95% CI) | 18%, 234/1289 (16 to 20.4) | ||

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | 14.1 (9.90 to 19.2) | 73.9 (67.8 to 79.4) | 75.2 (69.2 to 80.6) |

| Specificity (95% CI) | 99.3 (98.6 to 99.7) | 96.8 (95.5 to 97.8) | 98.5 (97.5 to 99.1) |

| Positive PV (95% CI) | 82.5 (67.2 to 92.7) | 83.6 (77.8 to 88.3) | 91.7 (86.8 to 95.2) |

| Negative PV (95% CI) | 83.9 (81.7 to 85.9) | 94.4 (92.8 to 95.7) | 94.7 (93.2 to 96.0) |

| Positive LR (95% CI) | 21.3 (9.50 to 47.5) | 22.9 (16.3 to 32.2) | 49.6 (30.3 to 81.1) |

| Negative LR (95% CI) | 0.90 (0.80 to 0.90) | 0.30 (0.20 to 0.30) | 0.30 (0.20 to 0.30) |

*Excludes individuals taking diabetes treatment that day (n=6), did not fast before OGTT as instructed (n=5) or did not complete the OGTT (n=16).

†Composite reference standard: OGTT ≥200 mg/dL or cFBG ≥200 mg/dL. Seventy patients with cFBG≥200 were not tested by OGTT.

cFBG, capillary fasting blood glucose; LR, likelihood ratio; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; PV, predictive value.

Table 3.

Diagnostic accuracy of the urine glucose test strip by patient characteristics

| Patient characteristic: mean (SD) or % | Diabetic* | Non-diabetic* | ||

| True positive n=33 |

False negative n=201 |

False positive n=7 |

True negative n=1048 |

|

| Age | 57 (9.3) | 58 (10.5) | 56 (11.9) | 50 (15.5) |

| Female (%) | 81.8 | 74.6 | 85.7 | 75.3 |

| Venous fasting blood glucose | 207 (75.3) | 166 (73.2) | 95 (16.9) | 90 (13.1) |

| Venous blood glucose 2 hours after OGTT | 310 (60.8) | 275 (62.2) | 115 (43.2) | 120 (31.0) |

| Change in venous blood glucose during OGTT | 160 (50.8) | 146 (49.8) | 20 (47.7) | 30 (30.0) |

| HbA1c | 10 (2.3) | 8 (2.4) | 6 (0.7) | 5 (0.5) |

| BMI | 24 (3.9) | 24 (3.9) | 26 (3.2) | 23 (4.1) |

| High BMI (%) | 33.3 | 36.8 | 57.1 | 29.0 |

| Waist circumference above cut-off (%) | 60.6 | 61.7 | 71.4 | 42.8 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 132 (24.9) | 130 (20.6) | 146(14.0) | 122 (20.2) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 85 (9.6) | 84 (11.7) | 87 (6.5) | 80 (12.1) |

| Elevated blood pressure (%) | 15.2 | 20.9 | 14.3 | 11.3 |

| Take treatment for high blood pressure (%) | 18.2 | 11.4 | 28.6 | 7.1 |

| Total cholesterol | 242 (62.3) | 227 (69.8) | 240 (63.1) | 213 (56.3) |

| Proteinuria (n=1116)† (%) | 20.0 | 17.2 | 0 | 3.0 |

| Albuminuria (%) | 51.5 | 47.8 | 14.3 | 21.7 |

| Abnormal albumin/creatinine ratio (%) | 39.3 | 39.3 | 14.3 | 17.3 |

Bold, significantly different (P≤0.05) by Student’s t-test or Χ2 test.

*Diagnosis by the composite reference standard: venous OGTT ≥200 mg/dL or cFBG ≥200 mg/dL. Seventy patients with cFBG ≥200 were not tested by OGTT.

†Four missing values; 169 indeterminate measurements not included in analysis.

BMI, body mass index; cFBG, capillary fasting blood glucose; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

The prevalence of diabetes (diagnosed by the composite reference standard) was significantly higher in participants who were 50 years of age or older compared with those under 50 years (24% vs 9.6%); those with high BMI compared with those with normal BMI (22% vs 17%) and those with greater waist circumference compared with those with normal waist (24% vs 13%), but was the same in men and women (table 4). The diagnostic accuracy of the urine glucose test strip was similar among subgroups of patients with various cofactors, with overlapping CIs (table 4). Additionally, multivariate and univariate logistic regression analyses also indicated that the diagnostic accuracy of the index test was not significantly impacted by these cofactors.

Table 4.

Diagnostic accuracy of urine glucose test strip by participant cofactors (n=1289)*

| Results | Cofactors | |||||||

| Age | BMI † | Gender | Waist circumference ‡ | |||||

| <50 | ≥50 | <25 | ≥25 | Male | Female | Normal | High | |

| Number of participants | 531 | 758 | 895 | 393 | 317 | 972 | 691 | 598 |

| True positive (n) | 8 | 25 | 22 | 11 | 6 | 27 | 13 | 20 |

| False positive (n) | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 5 |

| False negative (n) | 43 | 158 | 127 | 74 | 51 | 150 | 77 | 124 |

| True negative (n) | 477 | 571 | 743 | 304 | 259 | 789 | 599 | 449 |

| True diabetes prevalence § |

9.6% (7.2 to 12.4) | 24% (21.0 to 27.4) | 17% (14.0 to 19.3) | 22% (18.0 to 26.0) | 18% (14.0 to 22.7) | 18% (16.0 to 20.8) | 13% (11.0 to 15.8) | 24% (21.0 to 27.7) |

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | 15.7 (7.0 to 28.6) | 13.7 (9.0 to 19.5) | 14.8 (9.5 to 21.5) | 12.9 (6.6 to 22.0) | 10.5 (4.0 to 21.5) | 15.3 (10.3 to 21.4) | 14.4 (7.9 to 23.4) | 13.9 (8.7 to 20.6) |

| Specificity (95% CI) | 99.4 (98.2 to 99.9) | 99.3 (98.2 to 99.8) | 99.6 (98.8 to 99.9) | 98.7 (96.7 to 99.6) | 99.6 (97.9 to 100) | 99.2 (98.4 to 99.7) | 99.7 (98.8 to 100) | 98.9 (97.4 to 99.6) |

| Positive PV (95% CI) | 72.7 (39 to 94.0) | 86.2 (68.3 to 96.1) | 88 (68.8 to 97.5) | 73.3 (44.96 to 92.2) | 85.7 (42.1 to 99.6) | 81.8 (64.5 to 93.0) | 86.7 (59.5 to 98.3) | 80 (59.3 to 93.2) |

| Negative PV (95% CI) | 91.7 (89 to 94) | 78.3 (75.2 to 81.3) | 85.4 (82.9 to 87.7) | 80.4 (76.1 to 84.3) | 83.5 (78.9 to 87.5) | 84 (81.5 to 86.3) | 88.6 (86 to 90.9) | 78.4 (74.8 to 81.7) |

| Positive LR (95% CI) | 25.1 (6.9 to 91.6) | 19.6 (6.9 to 55.7) | 36.7 (11.1 to 121) | 10.0 (3.3 to 30.5) | 27.4 (3.4 to 223) | 20.2 (8.5 to 48.2) | 43.4 (10.0 to 189) | 12.6 (4.8 to 33) |

| Negative LR (95% CI) | 0.8 (0.8 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.8 to 0.9) | 0.9 (0.8 to 0.9) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 0.85 (0.80 to 0.91) | 0.86 (0.79 to 0.94) | 0.87 (0.82 to 0.93 |

Bold, significantly different (P≤0.05), Χ2 test.

*Excludes individuals taking diabetes treatment that day (n=6), did not fast before OGTT as instructed (n=5) or did not complete the OGTT (n=16).

†n=1288.

‡High waist circumference =>90 cm for men, >80 cm for women.19

§Composite reference standard: OGTT ≥200 mg/dL or cFBG ≥200 mg/dL. Seventy patients with cFBG≥200 were not tested by OGTT.

BMI, body mass index; cFBG, capillary fasting blood glucose; LR, likelihood ratio; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; PV, predictive value.

Discussion

Urine glucose test strips had much lower sensitivity than either cFBG or HbA1c, but all three tests offered high specificity. Patients who tested positive with the urine glucose test who were confirmed to have diabetes by the reference standard (true positives) had higher FBG, higher OGTT and higher HbA1c levels compared with the false negative group (urine test negative in patients with diabetes), suggesting that the urine glucose test may identify individuals with poor glycaemic control. This suggests a subset of patients with diabetes is being identified that may potentially be at higher risk of advancing complications or comorbidities and who may benefit the most from further care.20 In addition, testing for urine glucose was highly specific (99%), with positive LRs in the 20 s, indicating that when positive, this test is highly indicative of diabetes.

The prevalence of diabetes in the MoPoTsyo population in Cambodia was 18%. This is much higher than the national prevalence for Cambodia, which is reported at 3.0%.1 This may be due to the high proportion of individuals over 50 years of age in our study population, which could be explained by a participation bias towards those who were able to miss a day of work to attend a clinic visit. Additionally, our study took place in a rapidly changing urban population, which had a 2.4 times higher diabetes prevalence in the STEP survey country report from 2010.21

A wide range of sensitivities for the urine glucose test strip has been reported, and its use remains controversial. A review in 2000 found six adequately designed studies that reported performance of urine test strips for glucose.8 Among these, sensitivities in two reports of fasting patients were 16% and 35%; two using random samples found sensitivities of 18% and 64% and three using postprandial and post-load measurements reported sensitivities between 39% and 48%. This review concluded that blood glucose measurements were preferred over urinary glucose or HbA1c, and particularly, postprandial over fasting measures. Another review found five studies reporting a range of sensitivity from 18% to 74% for urine glucose test strips.7 The review concluded that urine glucose test strips are not sufficient for screening for diabetes.

This is one of the first studies to determine the prevalence of diabetes in Cambodia and report on the screening accuracy of urine glucose test strips which are commonly used as screening tests in this setting. We used a prospective community-based design and had a large sample size with high participation rate. The study had several limitations. First, we used a composite reference test and those with cFBG >200 mg/dL were not evaluated by the OGTT. When evaluating the index test of cFBG, the index test is included in the reference test, though at a different threshold. This can cause incorporation bias resulting in an inflated test accuracy. Here, the three different index tests are included for comparison; however, the likely overestimation of diagnostic accuracy for cFBG is important to keep in mind. While OGTT is considered the gold standard reference test for assessing diagnostic accuracy, there has been some question of its performance. Two studies in China, each on more than 200 participants, found that the reproducibility of the OGTT was 56%22 and 66%.23 Though our choice of the reference standards, particularly OGTT, could have affected our study results, its use allows comparison of our results with those in a number of other studies. Second, the urine glucose test was self-administered and self-reported. While this was pragmatic and aligns with the practices at MoPoTyso and other clinical settings in Cambodia, errors in interpreting the test result could influence accuracy. We were not able to repeat this test when patients attended their clinic visit as they were fasting at the clinic visit, and thus their urine would not have been the random non-fasting urine test obtained at home. Third, we were not able to obtain haemoglobin levels (or test for haemoglobin variants) as these tests are not available in this setting, and hence cannot assess the impact of anaemia or haemoglobinopathy on test performance.24 Fourth, glucose test strip accuracy may be subject to effects of heat and humidity, and we were not able to explore their possible impact on our results.

For clinicians working in settings similar to ours, the question is how useful is the urine glucose test as a screening or diagnostic test, and is it ‘better than nothing’? The low sensitivity certainly reduces the value of this test as a screening tool, but the high specificity means that positive tests can be used to rule in patients with diabetes, suggesting that urine glucose may have some diagnostic value in this setting. The false positive rate was extremely low, and only seven patients without disease were identified as positive by urine glucose test strip. From a population perspective, the value of a low cost, poorly sensitive yet highly specific test for diabetes is unclear in terms of balancing the opportunity to identify a subset of patients with less well-controlled diabetes who would not have been identified otherwise, with the downside of a high false negative rate.25

Not surprisingly, usability parameters and cost make urine glucose test strips a highly desirable test in this and other low-resource settings.9 Product attributes such as low complexity and infrastructure requirements, short time to results and low participant burden greatly contribute to the acceptability and desirability of the screening tool. The large patient burden and the frequent inability to comply with fasting requirements reduce the feasibility of using OGTT or FBG tests. While HbA1c testing does not require fasting, current tests are too expensive for use in most low-income countries. The role of a poorly sensitive test like urine glucose in resource poor settings such as Cambodia is debatable; on the one hand, the test will identify some patients previously undiagnosed, and assuming treatment can be initiated will reduce severity of complications from this disease. On the other hand, the test will miss the majority of patients with diabetes, thus risking a false reassurance, further postponement of diagnosis and risking patient’s respect for the healthcare system.

There may be strategies to improve the performance (particularly sensitivity) of the urine glucose test strip. First, using the presence of risk factors such as high waist circumference or BMI may increase the pretest probability of diabetes and lead to improved performance. In our study, the sensitivity of the urine glucose test strip among overweight men with high waist circumference was twice the overall sensitivity (29% vs 14% respectively). Second, using random, postprandial or glucose-loaded measurements may be superior than fasting because the renal threshold for glucose is more often reached in non-fasting states.8 Third, improving the limit of detection may be possible by modifications in the test strip itself or improvement in the way it is read either manually (with trained users) or automatically (with electronic reading devices). Finally, increasing screening frequency may be feasible in low-resource settings, if the urine glucose test strip truly does identify a smaller but more advanced fraction of patients with diabetes.

Conclusion

Low cost, easy to use diabetes screening, diagnosis and monitoring tools are essential for low-resource communities with minimal infrastructure. While the urine glucose test strip has some value as a screening test in these settings, its performance is far from optimal. Progress is urgently needed to improve the performance, availability and access of essential testing technologies for diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Borey Santepheap Community in Cambodia (Phnom Penh Municipality, District Dangkao, Commune Chom Chao) for participating in this study. We also acknowledge the input of Dr Annette Fitzpatrick and Dr Jim LoGerfo from the University of Washington.

Footnotes

Contributors: MHvP, SB, TN, HM and BHW designed the study; MHvP, SB, TN and BHW implemented the study; HLS, MT, HM and BHW analysed and interpreted the data; HLS, MHvP, FD, MT, HM and BHW contributed to writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from Medtronic Foundation and received additional support from PATH and the University of Washington Department of Family Medicine. The funding source had no involvement in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript or the decision to publish the results.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: The protocol was approved by the PATH Research Ethics Committee and the National Ethics Committee for Health Research (Cambodia Institutional Review Board).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data sets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 7th Edn Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol Rev 2013;93:137–88. 10.1152/physrev.00045.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1343–50. 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dyerberg J, Pedersen L, Aagaard O. Evaluation of a dipstick test for glucose in urine. Clin Chem 1976;22:205–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van der Sande MA, Walraven GE, Bailey R, et al. Is there a role for glycosuria testing in sub-Saharan Africa? Trop Med Int Health 1999;4:506–13. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taal MW, Chertow GM, Marsden PA, et al. Laboratory Assessment of Kidney Disease: Glomerular Filtration Rate, Urinalysis, and Proteinuria. In Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wei OY, Teece S. Best evidence topic report. Urine dipsticks in screening for diabetes mellitus. Emerg Med J 2006;23:138 10.1136/emj.2005.033456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Engelgau MM, Narayan KM, Herman WH. Screening for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2000;23:1563–80. 10.2337/diacare.23.10.1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization. Screening for Type 2 Diabetes. Report of a World Health Organization and International Diabetes Federation meeting. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Pelt M. Improving access to education and care in Cambodia. Diabetes Voice 2009;54. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Taniguchi D, LoGerfo J, van Pelt M, et al. Evaluation of a multi-faceted diabetes care program including community-based peer educators in Takeo province, Cambodia, 2007-2013. PLoS One 2017;12:e0181582 10.1371/journal.pone.0181582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Olmen J, Eggermont N, van Pelt M, et al. Patient-centred innovation to ensure access to diabetes care in Cambodia: the case of MoPoTsyo. J Pharm Policy Pract 2016;9:1 10.1186/s40545-016-0050-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ 2015;351:h5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization. WHO STEPS surveillance manual. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Obuchowski NA. Sample size calculations in studies of test accuracy. Stat Methods Med Res 1998;7:371–92. 10.1177/096228029800700405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. King H, Keuky L, Seng S, et al. Diabetes and associated disorders in Cambodia: two epidemiological surveys. Lancet 2005;366:1633–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67662-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2016 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin Diabetes 2016;34:3–21. 10.2337/diaclin.34.1.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bartoli E, Fra GP, Carnevale Schianca GP. The oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) revisited. Eur J Intern Med 2011;22:8–12. 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization. Waist circumference and waist-hip ratio: report of a WHO expert consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nathan DM, Genuth S, Lachin J, et al. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993;329:977–86. 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. University of Health Sciences Cambodia, Ministry of Health Cambodia. Prevalence of non-communicable disease risk factors in Cambodia; STEPS Survey Country Report. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: University of Health Sciences Cambodia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu M, Pan CY, Jin MM, et al. [The reproducibility and clinical significance of oral glucose tolerance test for abnormal glucose metabolism]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2007;46:1007–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ko GT, Chan JC, Woo J, et al. The reproducibility and usefulness of the oral glucose tolerance test in screening for diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors. Ann Clin Biochem 1998;35(Pt 1):62–7. 10.1177/000456329803500107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. English E, Idris I, Smith G, et al. The effect of anaemia and abnormalities of erythrocyte indices on HbA1c analysis: a systematic review. Diabetologia 2015;58:1409–21. 10.1007/s00125-015-3599-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Flessa S, Zembok A. Costing of diabetes mellitus type II in Cambodia. Health Econ Rev 2014;4:24 10.1186/s13561-014-0024-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.