Abstract

Objective

We set out to document how NHS trusts in the UK record and share disclosures of conflict of interest by their employees.

Design

Cross-sectional study of responses to a Freedom of Information Act request for Gifts and Hospitality Registers.

Setting

NHS Trusts (secondary/tertiary care organisations) in England.

Participants

236 Trusts were contacted, of which 217 responded.

Main outcome measures

We assessed all disclosures for completeness and openness, scoring them for achieving each of five measures of transparency.

Results

185 Trusts (78%) provided a register. 71 Trusts did not respond within the 28 day time limit required by the FoIA. Most COI registers were incomplete by design, and did not contain the information necessary to assess conflicts of interest. 126/185 (68%) did not record the names of recipients. 47/185 (25%) did not record the cash value of the gift or hospitality. Only 31/185 registers (16%) contained the names of recipients, the names of donors, and the cash amounts received. 18/185 (10%) contained none of: recipient name, donor name, and cash amount. Only 15 Trusts had their disclosure register publicly available online (6%). We generated a transparency index assessing whether each Trust met the following criteria: responded on time; provided a register; had a register with fields identifying donor, recipient, and cash amount; provided a register in a format that allowed further analysis; and had their register publicly available online. Mean attainment was 1.9/5; no NHS trust met all five criteria.

Conclusion

Overall, recording of employees’ conflicts of interest by NHS trusts is poor. None of the NHS Trusts in England met all transparency criteria. 19 did not respond to our FoIA requests, 51 did not provide a Gifts and Hospitality Register and only 31 of the registers provided contained enough information to assess employees’ conflicts of interest. Despite obligations on healthcare professionals to disclose conflicts of interest, and on organisations to record these, the current system for logging and tracking such disclosures is not functioning adequately. We propose a simple national template for reporting conflicts of interest, modelled on the US ‘Sunshine Act’.

Keywords: conflict of interest, gifts and hospitality, freedom of information act (foia), pharmaceutical industry, nhs trusts

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We included all NHS Trusts in England.

Responding to Freedom of Information Act (FoIA) requests is a statutory responsibility: we therefore yielded a high (91.9%) response rate.

Trusts who did not respond to our FoIA request may have poorer COI disclosure practices: we may therefore have underestimated the extent of the problems identified.

Introduction

$2.4 billion was given to US doctors by the pharmaceutical industry in 2015.1 48% of all doctors in the US received such payments, the majority of which were ‘general’ payments rather than payments for research. The motive for the pharmaceutical industry in spending this money is widely held to be marketing.2 In the UK the 2015 spend has been reported by industry as £111 million, excluding payments for research.3 Direct gifts and inducements have been prohibited since 2010 by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI), an industry membership organisation that has also become a voluntary regulator of the pharmaceutical industry.4 However, pharmaceutical companies can still pay doctors and other clinicians5 6 to deliver Continuing Professional Development (CPD) lectures or sponsor their attendance at conferences. They can directly provide ‘training’ or ‘updates’ to clinicians, often accompanied by generous catering. They can also sponsor educational and academic events within hospitals, provide restaurant meals, and send marketing staff (commonly known as ‘drug reps’) to meet with doctors directly. Recent systematic reviews7 8 have found an association between contact between prescribers and the pharmaceutical industry and a decrease in their prescribing quality, or an increase in inappropriate prescribing and prescribing cost.

Doctors and other healthcare professionals are required to declare all financial conflicts of interest so that their appropriateness, and any possible impact on professional behaviour, can be assessed independently and transparently. The Physician Payment Sunshine Act (PPSA) Act in the US requires that all payments to doctors are declared onto a single central database that is openly accessible. UK guidelines are more fragmented. The GMC,9 and some other professional organisations10 11 require healthcare providers to declare any potential conflict of interest to both their patients and their employers. NHS England circulated ‘Standards of Business Conduct’ to NHS trusts in 1993,12 which stipulates that all NHS staff ‘should’ declare potential conflicts of interest to their employers, and that these ‘should’ be recorded in a Gifts and Hospitality Register. NHS trusts administer hospitals, mental health and specialist community services, and employ many of the healthcare professionals in the UK. The NHS England guidelines are not binding on trusts, although many do incorporate them into local guidelines and therefore staff contracts. Industry transparency requirements are similarly problematic. In 2016 the ABPI released a database of all payments by UK pharmaceutical companies to healthcare professionals. However, those in receipt of these payments could opt out of having their name declared on this database, leaving the payment recorded only in aggregate for each company. This, and other problems with the database, means that it provides an ‘illusion of transparency’ rather than an auditable resource.13

Given the problems with industry disclosure it is hoped that declarations to NHS trusts might provide a better route for transparency around industry payments to healthcare professionals. There has never been a systematic examination of the existence and contents of these registers. We therefore set out to request and describe all UK NHS Gifts and Hospitality registers.

Methods

Our objectives were to: request all COI registers from all English NHS trusts; describe whether they were delivered; assess the contents and structure of hospitals’ disclosure registers; and generate summary statistics describing disclosures overall.

Obtaining COI registers

We sent all 236 NHS Trusts in the UK a Freedom of Information Act (FoIA) request asking for a copy of their Gifts and Hospitality Register for the financial year 2015/16. No Trusts were excluded. We also requested the number of staff members who have been the subject of internal investigations or disciplinary proceedings in relation to purported conflicts of interest, or the failure to declare them, and the outcomes of these investigations or proceedings. The Freedom of Information Requests were sent out in the 2 weeks after ninth July 2016. Contact details were obtained from each Trust’s website and placed into a spreadsheet; a Google Apps script was then used to send standardised emails to each Trust.14 We logged replies until mid-November 2016. Trusts which did not reply were followed up twice. Summary statistics are presented on the proportion of Trusts sending their COI register in total; and the proportion responding within the timescale stipulated by the Act (20 working days). We describe the proportion invoking section 12 to avoid disclosing (a refusal on grounds of cost), and those citing section 40 to remove names from the register (on grounds of privacy). We also logged those trusts who directed us to the ABPI’s summary disclosure database on which healthcare professionals can choose to have their payments anonymised.

Assessing the contents and structure of hospitals’ disclosure registers

We extracted the following structured data to describe the contents of each hospital’s disclosure register: the format the information was delivered in (PDF, document, spreadsheet, scans of handwritten sheets, or text within an email); and the completeness of information given about each individual disclosure (the name of the recipient, the name of the company providing the gift or hospitality, the cash amount of the gift). In addition, we noted whether the register was already publicly available online. We also checked each register for any identifying patient data. We generated summary statistics to describe these contents. Data extraction was performed by one of the authors (HRF). Standards and classifications were discussed with other authors (NJD and BG) before data were extracted. We generated a transparency index assessing whether each Trust met the following criteria: (1) responded on time; (2) provided a register; (3) had a register with fields identifying donor, recipient, and cash amount; (4) provided a register in a format that allowed further analysis; and (5) had their register publicly available online.

Summary statistics on disclosures

Because the data provided was in multiple formats, and frequently not structured, it could not be aggregated for analysis. One author (HRF) manually transcribed data from a random sample of 20 Trust’s disclosures and generated summary statistics on: the number of disclosures per Trust; the size of each individual disclosure; the profession of those making disclosures; and the source of the payment (industry or patient). This sample size was chosen to represent approximately 10% of disclosures, and was limited by researcher time. Where names of staff were given but not job roles, organisation web pages were used to try to ascertain the profession of the individual making the disclosure. The field of commercial entities was ascertained through their company webpages. Where a range of cash values were given (eg, ‘<£50’) the upper value was used.

Analysis

All analyses were conducted in Google Sheets.

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in the design or conduct of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants.

Results

Obtaining trust disclosure registers

Of the 236 trusts sent a Freedom of Information request, 217 responded (91.9%). 185 Trusts (78.4%) provided a copy of their Gifts and Hospitality register for the financial year 2015/16. 10 Trusts (4.2%) declined to share their disclosure register and invoked Section 12 of the FoIA, an exemption available where a public body can assert that the cost of collating and sharing information would exceed £450. Other reasons given for not providing a Gifts and Hospitality register included: no register was held (18/217, 8.3%); the register contained no entries (5/217, 2.3%); the register was on paper only (5/217, 2.3%); and other reasons (3/217, 1.3%). Of those trusts that did not hold a register, two claimed it was not needed because their staff were contractually prohibited from accepting such payments, and six Trusts sent data from the ABPI instead. In three of these cases, a version of the ABPI database was sent with the names of the recipients redacted, even though this information is freely available online with names unredacted. 12 Trusts (5.5%) suggested that we refer to the ABPI database for further or more complete information.

Contents and structure of hospitals’ disclosure registers

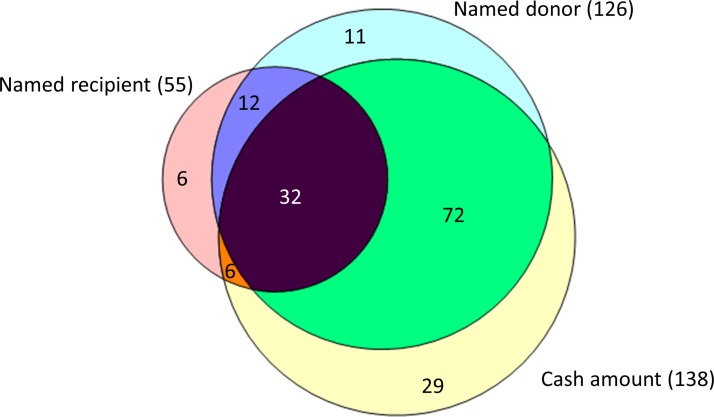

Of the 185 registers received, only 31/185 (16.7%) were complete – containing fields recording the name of the recipient, the name of the donor and the cash amount received. However, even when there were fields to record these data, incomplete records were common. 126 registers (68.1%) did not have a field for the name of the recipient. 14 Trusts (7.6%) explicitly stated that they had redacted this field under Section 40 of the Freedom of Information Act, arguing that it constituted personal information. Some Trusts redacted only the names of staff under a certain pay band. 59 registers (31.9%) did not have a field for the name of the donor. 47 registers (25.4%) did not have a field for the cash value of the gift or hospitality. The overlap between these elements is shown in a Venn diagram in figure 1. Of note, 18 registers (9.7%) contained none of: recipient name, donor name, or declaration of the cash amount received.

Figure 1.

Venn diagram showing the information contained in the registers received.

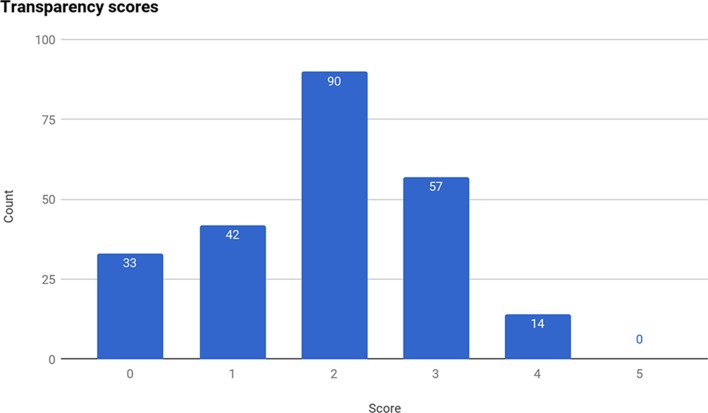

The proportion of Trusts meeting each of our five transparency criteria is given in table 1; the distribution of the total number of criteria met is given in figure 2. Mean attainment was 1.9/5. No NHS trust met all five criteria.

Table 1.

Number and percentage of trusts achieving each transparency criteria

| Transparency element | Number of trusts achieving criteria | Proportion of trusts achieving criteria |

| Responded on time | 165 | 69.9% |

| Provided a register | 185 | 78.4% |

| Contained fields for named donor, named recipient and cash amount | 31 | 13.1% |

| Provided the register in a format that allowed further analysis (ie, spreadsheet, csv) | 53 | 22.5% |

| Made register publicly available online | 15 | 6.4% |

Figure 2.

Distribution of total number of transparency criteria met, across all NHS Trusts.

Breaches of patient confidentiality in trust responses

11/185 (5.9%) of the registers contained information which could potentially breach patient confidentiality - for example, giving the name of the patient or relative who had given a gift to a healthcare professional. To protect patients’ confidentiality we have therefore removed the disclosures made by these Trusts from our shared dataset.

Data on disciplinary hearings

199 trusts returned information on the number of disciplinary hearings related to conflict of interest. Of these, 174 had had none. The mean number per Trust was 0.2. The definition of ‘conflict of interest’ was interpreted broadly by Trusts and included actions such as having a second job and working while on sick leave.

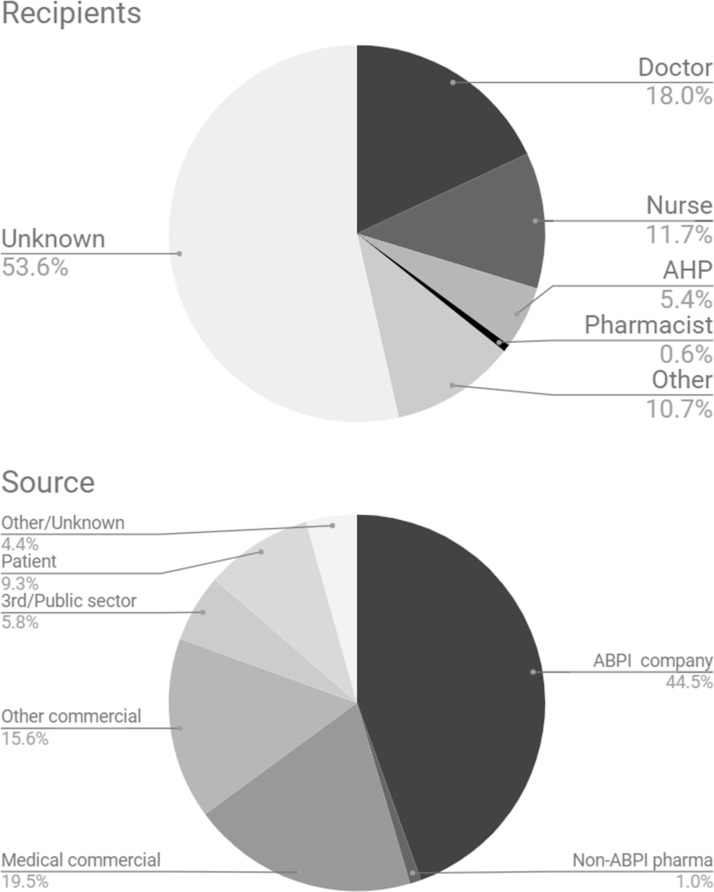

Summary statistics on disclosures

Data from 20 trusts was transcribed into spreadsheet format to produce summary statistics. The registers transcribed contained a mean of 30.8 entries (range 4–175, total 616). 428 entries gave the cash amount of the declaration, totalling £162,245 - a mean declaration size of £379. However, there was substantial rightward skew with a median declaration of £127.50 and 122 entries with value £30 or less. Further data about the sources and recipients of the payments on these registers is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Recipients and sources of the payments disclosed in the 20 randomly selected registers we quantified.

Trusts with a ‘zero’ disclosure

Unexpectedly, five trusts stated that they had no entries on their register, and another two delivered empty registers. For those trusts which described or returned no entries, we found 230 records in the ABPI disclosure database relating to payments to individuals employed at these Trusts, totalling £119,851.35. In addition, we found 107 records of payments to these trusts directly, an average of £22 293 per trust.

Two of these trusts stated that a disclosure register was not needed as their policies prohibited staff from taking such payments. One, East London Foundation Trust, stated: ‘Trust Policy prohibits the acceptance of payments from pharmaceutical companies to members of staff. We therefore have no such register.’ A search of the ABPI database (dated 19/04/2017) returned 7 payments to five individuals who registered their institution as East London Foundation Trust, with a total value of £2050.63. Hertfordshire Community NHS Foundation Trust stated: ‘We do not have a ‘gifts’ register, as under the Trust’s Standards of Business Conduct Policy (previously supplied) a gift is either acceptable (in which case it doesn’t need to be reported) or it is not acceptable.’ A search of the ABPI database returned 5 payments to four individuals who registered their institution as Hertfordshire Community NHS Foundation Trust, totalling £734.43. Since clinicians are permitted to withhold disclosure of their data on the ABPI, and non-disclosure rates on the ABPI database are high, this is likely to be an incomplete list.

Data sharing

All responses15 and all analyses16 are shared on FigShare. Where we have concerns that Trusts have breached patient confidentiality in their returns, we have redacted any potential personal information. In order to illustrate the issues described in summary text above we have also shared a range of illustrative examples17: an example of a register which mostly lists trivial gifts from patients (3.1), a register which mostly discloses additional employment (3.2), a register which covers only board members and not staff (3.3), and data structure which is almost impenetrable to analysis and audit (3.4).

We have set up a new website (coi.theycareforyou.org), to make data on Trusts' COI declarations more accessible for all interesed parties; all data from our paper is shared accessibly here. NHS Trusts are welcome to submit their most up-to-date register to this site.

Conclusion

Summary of findings

Overall, recording of the interests of employees by NHS trusts is poor. None of the NHS Trusts in England met all transparency criteria by: (1) responding on time; (2) providing a register; (3) that register having a complete data structure; (4) providing the data in a reusable (spreadsheet) format; (5) making the register publicly available online. 59/185 trusts did not record the donor of the payment or hospitality, which makes it impossible to assess the conflict of interest. 18 trusts did not hold a disclosure register at all.

Strengths and limitations of the study design

The use of a statutory framework - the Freedom of Information Act (FoIA) - led to a very high (91.9%) response rate in this study. The presence of missing data is in itself informative: responses that were absent or incomplete are an important finding. However, it is possible that Trusts which failed to respond to a FoIA request are also failing on other administrative issues. The absence of their disclosures may result in our study underestimating the problems with Trust registers by only coding those from Trusts which did respond.

Findings in context

We have previously outlined the problems with the ABPI’s ‘Disclosure UK’ as a platform for reporting conflicts of interest in particular that healthcare professionals can choose to redact themselves from that dataset, and routinely do so.13 Barriers to accessing UK COI data mean that there is little prior work analysing such disclosures. In the US, disclosures are managed on a national level by the federal government. The PPSA was passed as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010.18 The PPSA requires industry to report all payments to doctors (but not other healthcare professionals, who also receive significant attention from pharmaceutical marketing5 6) and teaching hospitals in excess of $10, to the Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). This includes payments for ‘general’ categories such as educational materials or food and beverage, as well as funding for research and ownership stakes in the reporting entities. CMS then makes this data available through the publicly searchable Open Payments website. The Open Payments website19 currently houses all reported payments from first August 2013 to 31 st December 2016. Over this time, the Open Payments database has grown to include details of nearly $25 billion worth of payments to doctors and teaching hospitals including $7 001 435 854 in general payments to 9 05 238 individual doctors. For the full 3.5 years covered by the PPSA, the mean number of general (non-research) payments to doctors is 43 and the mean amount received from these payments is $7734.36.20

The comprehensive and accessible nature of Open Payments has allowed researchers to assess and quantify the impact of pharmaceutical payments. For example, there is a dose-response relationship between receiving more pharmaceutical payment and increased prescribing cost21 and branded drug prescribing,22 which has been demonstrated by linking publicly available Medicare prescribing data with Open Payments data.23 Others have used the data to characterise industry payments within their specialty24 25 or auditing targeted groups such as guideline authors.26 27 While the programme is still new, there is evidence that industry spending may be decreasing since the launch of Open Payments.28 29 Some researchers are even beginning to use PPSA data to examine association between relationships with industry and clinical practice.30 The public availability of the data has also been an asset to investigative journalism into the medical profession.31 32

However, the PPSA and Open Payments have faced criticisms. They exclude non-doctor prescribers from required reporting5 6 33 and have been unpopular with some doctors for a variety of reasons.34 As the US experience shows, creating centralised and standardised disclosure databases for physicians presents challenges around how to collect, validate, and present data in accurate, useful, and meaningful ways. These difficulties, however, should not dissuade attempts to improve on the current status quo on countries like the UK. As our findings show, when disclosure is required only through broad, unspecific, and unenforced regulations its utility and accessibility is greatly compromised. Efforts like the ABPI database also fall short of a programme like Open Payments as it is a voluntary endeavour without the authority of the state to require reporting and compel compliance. These limitations preclude the prospect of any comprehensive research on the state of COI in the UK, an area that is flourishing in the US among more comprehensive disclosure standards and despite programmatic limitations.

Interpretation and policy implications

The current system of piecemeal private declarations to NHS employers, and optional declarations through the ABPI’s ‘Disclosure UK’, is not delivering transparency on COI in the UK. Through our analysis of these records, we identify four main barriers to transparency.

First, there is no central system for disclosures to employers. This allows wide variations in the standards of reporting and recording COI. Many healthcare professionals will also have more than one public sector employer simultaneously, or sequentially over a short time period. Declaring separately with each employer makes it unlikely that any one organisation will have access to full information about their employees. Second, there is poor auditing of records, and a lack of evidence that contents are reflected on locally. Most Trusts allowed incomplete records to be returned, seemed not to compare their declarations with other sources such as the ABPI database, and appeared happy to accept implausibly empty registers. If this information is collected but not examined or acted on, there is a risk that this gives an unwarranted appearance of transparency and rigorous management. Thirdly, the variation in types of information disclosed and how it was presented suggests that there is lack of clarity about what constitutes a COI; and a lack of consensus around how to handle diverse categories of COI such as income from private work, interactions with industry, and gifts from patients. Lastly, COI records are generally not made public. Most Trusts did not place their registers on the internet, and most did not give the names of recipients on their COI register.

Some NHS Trusts cited the Freedom of Information Act as a reason to withhold the identity of recipients, specifically Section 40 of the Act, which aims to protect individuals’ personal privacy. In our view there are good grounds to argue that this is not a legitimate use of Section 40: employees were largely acting in a professional capacity when they received payments; disclosure represents a legitimate public interest; FoIA emphasises the importance of ‘transparency and accountability’ when considering personal data disclosure; healthcare professionals have existing disclosure obligations to professional regulators (for example, the GMC requires doctors to inform their patients about any conflicts of interest); and staff expectations at the time of disclosure to a Trust are therefore likely to have been that this COI information should or could be made public. These issues can be resolved through an extensive process of appeals to the Information Commissioner, although this process may take years rather than months.

On ninth February 2017, NHS England published new guidance about managing conflict of interest within the NHS.35 This guidance aims to offer more complete and consistent principles for managing COI in NHS Trusts, CCGs and NHS England. The guidance emphasises that declarations must be collected and recorded, and recommends that the declarations of ’decision-making staff' are published (with names) on an organisation’s website. However, it is not binding on Trusts, and each organisation is free to adopt whatever standards it wishes. There is no proposal that the data should be centralised. The template disclosures ask for a ‘description’ of the interest in a single text field meaning that information can be omitted, or shared as unstructured free text, meaning that work done in the US on structured open data would continue to be impossible for UK disclosures. There is no guidance on identifying and managing the impact of pharmaceutical gifts and hospitality on prescribing. The new NHS COI policy would therefore not resolve the lack of transparency identified by our study.

We propose that the UK should ideally follow the lead set by the US, requiring simple annual compulsory disclosure of all financial COI by NHS healthcare professionals and donors to a central openly accessible database of COI, recording cash value, type of COI, donor, and recipient. Short of this, the GMC could remind doctors and Trusts that they expect the GMC requirement for open disclosure of COIs to patients to be upheld, and clarify that complete and openly shared NHS Trust COI registers allow doctors to meet their GMC requirements. This could be done with no changes to either legislation or the GMC document ‘Good Medical Practice’, which states: ‘you must be honest in financial and commercial dealings with patients employers, insurers and other organisations or individuals’ and ‘if you are faced with a conflict of interest, you must be open about the conflict, declaring your interest formally.’

Lastly, since COI is an issue for all those working in healthcare, not only doctors, we propose that it would be desirable to create and encourage the use of an openly accessible voluntary register where any healthcare professional, manager, or researcher in the UK could openly log their conflicts of interest in a structured searchable format as has been previously proposed for researchers in various territories.36–38 We are now seeking funds to deliver and maintain such a database.

Future directions

We aim to repeat this study to assess the impact of the new NHS guidance on disclosure, while acknowledging that such change is unlikely for the reasons given above. We also aim to expand our study to include Primary Care, where 55% of UK prescribing costs occur,39 by assessing the recording of COI by Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs). This has received attention recently after an audit in April 2016 showed that COI were inconsistently recorded within CCGs, and new binding guidance was released in July 2016.40

Conclusions

Information on COI is poorly collected, poorly managed, and poorly disclosed by NHS Trusts in England. The ongoing absence of transparency around COI in the UK may undermine public trust in the healthcare professions. Simple clear legislation and a requirement for open disclosure of COI to a central body, similar to that in the US, would present a simple and effective solution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

BG conceived the study with JM and DEC, who undertook a pilot audit in 2012. BG and HRF designed the study. HRF collected and analysed the data with input from ND and BG. HRF drafted the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript. BG and HRF conceived the associated website resource which was built by Seb Bacon. BG supervised the project. BG and HRF are guarantors.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare the following: JM reports grants from Oak Foundation, NordForsk, ESRC and Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research, and grants and other from Scottish Institute for Policing Research. JM has received a very small additional income (under £150 in total) for writing about problems around evidence and policy. These are all outside the submitted work. BG is funded by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation to conduct work on research integrity, but not specifically this project. No funder had any involvement in the study design or the decision to submit. BG has also received funding from the Wellcome Trust, the NHS National Institute for Health Research, the Health Foundation, and the World Health Organisation; he also receives personal income from speaking and writing for lay audiences on the misuse of science. ND is employed on BG’s grant from LJAF. HRF has received research funding from the Wellcome Trust, Green Templeton College, Guarantors of Brain and Oxford University Clinical Academic Graduate School. DEC has received research funding from the Jean Shanks Foundation and the Wellcome Trust. He has received software development funding from the Open Society Foundations, Jisc and the Public Library of Science (PLOS). He has received travel funding from PLOS and the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All underlying data and analysis is shared alongside this manuscript on FigShare.

References

- 1.Tringale KR, Marshall D, Mackey TK, et al. . Types and distribution of payments from industry to physicians in 2015. JAMA 2017;317:1774–84. 10.1001/jama.2017.3091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kremer STM, Bijmolt THA, Leeflang PSH, et al. . Generalizations on the effectiveness of pharmaceutical promotional expenditures. International Journal of Research in Marketing 2008;25:234–46. 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2008.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkes N. Doctors getting biggest payments from drug companies don’t declare them on new website. BMJ 2016;354:i3679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ABPI. Code of practice. 2016. http://www.abpi.org.uk/our-work/library/guidelines/Documents/code_of_practice_2016.pdf

- 5.Grundy Q, Bero L, Malone R. Interactions between non-physician clinicians and industry: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001561 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grundy Q, Bero LA, Malone RE. Marketing and the most trusted profession: the invisible interactions between registered nurses and industry. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:733–9. 10.7326/M15-2522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brax H, Fadlallah R, Al-Khaled L, et al. . Association between physicians' interaction with pharmaceutical companies and their clinical practices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0175493 10.1371/journal.pone.0175493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spurling GK, Mansfield PR, Montgomery BD, et al. . Information from pharmaceutical companies and the quality, quantity, and cost of physicians' prescribing: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000352 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.General Medical Council. Good medical practice. 2013. http://www.gmc-uk.org/static/documents/content/GMP_.pdf

- 10.Nursing and Midwifery Council. The code for professional standardsof practice and behaviourfor nurses and midwives. https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/nmc-code.pdf

- 11.General Pharmaceutical Council. Standards for pharmacy professionals. 2017. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/standards_for_pharmacy_professionals_may_2017_0.pdf

- 12.NHS Employers. Executive meetings for NHS staff. 2017. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4065045.pdf

- 13.Kmietowicz Z. Disclosure UK website gives "illusion of transparency," says Goldacre. BMJ 2016;354:i3760 10.1136/bmj.i3760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldman H, Goldacre B, DeVito N. Appendix 1. Figshare [epub ahead of print 22 Dec 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman H, Goldacre B, DeVito N. Appendix 2. Figshare [Epub ahead of print 22 Dec 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldman H, Goldacre B, DeVito N. Appendix 4. Figshare [Epub ahead of print 22 Dec 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldman H, Goldacre B, DeVito N. Appendix 3. Figshare [Epub ahead of print 22 Dec 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrawal S, Brown D. The physician payments sunshine act--two years of the open payments program. N Engl J Med 2016;374:906–9. 10.1056/NEJMp1509103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Open payments. https://www.cms.gov/openpayments/ (accessed 14 Jun 2017).

- 20.Devito NJ. Open payments general payment data through 2016. Figshare 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perlis RH, Perlis CS. Physician payments from industry are associated with greater medicare part d prescribing costs. PLoS One 2016;11:e0155474 10.1371/journal.pone.0155474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian J, Hansen RA, Surry D, et al. . Disclosure of industry payments to prescribers: industry payments might be a factor impacting generic drug prescribing. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2017;26:819–26. 10.1002/pds.4224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grochowski Jones R, Ornstein C. Matching industry payments to medicare prescribing patterns: an analysis. Pro Publica 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang JS. The physician payments sunshine act: data evaluation regarding payments to ophthalmologists. Ophthalmology 2015;122:656–61. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiner JA, Cook RW, Hashmi S, et al. . Factors associated with financial relationships between spine surgeons and industry: an analysis of the open payments database. Spine 2017;42:1412-1418 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramzi Dudum GWU, Omar Harfouch GWU, Heather A Young GWU, et al. . ACC/AHA guideline authors self-disclosed relationships compared to the open payments database: do discrepancies represent undisclosed conflicts of interest? In: GW research days 2016 - present, 2016. http://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/gw_research_days/2016/SMHS/60 (accessed 15 Jun 2017).

- 27.Mitchell AP, Basch EM, Dusetzina SB. Financial relationships with industry among national comprehensive cancer network guideline authors. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1628–31. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brockbank B, Amendola MF. IP175. Is there a difference in device- and medication-related payments made to vascular surgeons and interventional radiologists? insights from the open payments database. J Vasc Surg 2017;65:102S 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.03.191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gangopadhyay N, Chao AH. Abstract: the impact of the sunshine act open payments database on industry financial relationships in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2016;4(9 Suppl):37–8. 10.1097/01.GOX.0000502909.01781.d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook RW, Weiner JA, Schallmo MS, et al. . Effects of conflicts of interest on practice patterns and complication rates in spine surgery. Spine 2017;42:1322–9. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellis B, Hicken M, Hernandez S. How CNN reported on Nuedexta. CNN 2017. http://edition.cnn.com/2017/10/12/health/nuedexta-methodology-invs/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bankhead C. Derm guideline authors’ financial info questioned - industry payments common, often reported inaccurately. Medpage Today 2017. https://www.medpagetoday.com/publichealthpolicy/ethics/68640 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ladd E, Hoyt A. Shedding light on nurse practitioner prescribing. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners 2016;12:166–73. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2015.09.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chimonas S, DeVito NJ, Rothman DJ. Bringing transparency to medicine: exploring physicians' views and experiences of the sunshine act. Am J Bioeth 2017;17:4–18. 10.1080/15265161.2017.1313334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.NHS England Power Point template. Managing conflicts of interest in the NHS. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/guidance-managing-conflicts-of-interest-nhs.pdf

- 36.Dunn AG. Set up a public registry of competing interests. Nature 2016;533:9 10.1038/533009a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunn AG, Coiera E, Mandl KD, et al. . Conflict of interest disclosure in biomedical research: a review of current practices, biases, and the role of public registries in improving transparency. Res Integr Peer Rev 2016;1 10.1186/s41073-016-0006-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lichter AS, McKinney R. Toward a harmonized and centralized conflict of interest disclosure: progress from an IOM initiative. JAMA 2012;308:2093–4. 10.1001/jama.2012.51172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.NHS Digital. Prescribing costs in hospitals and the community, England 2015/16. http://www.content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB22302/hosp-pres-eng-201516-report.pdf

- 40.NHS England. NHS 70: celebrating 70 years of the NHS. https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2016/06/revsd-coi-guidance-june16.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.