Abstract

Introduction

Smoking remains the leading cause of preventable death in the USA but can be reduced through policy interventions. Computational models of smoking can provide estimates of the projected impact of tobacco control policies and can be used to inform public health decision making. We outline a protocol for simulating the effects of tobacco policies on population health outcomes.

Methods and analysis

We extend the Smoking History Generator (SHG), a microsimulation model based on data from the National Health Interview Surveys, to evaluate the effects of tobacco control policies on projections of smoking prevalence and mortality in the USA. The SHG simulates individual life trajectories including smoking initiation, cessation and mortality. We illustrate the application of the SHG policy module for four types of tobacco control policies at the national and state levels: smoke-free air laws, cigarette taxes, increasing tobacco control programme expenditures and raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco. Smoking initiation and cessation rates are modified by age, birth cohort, gender and years since policy implementation. Initiation and cessation rate modifiers are adjusted for differences across age groups and the level of existing policy coverage. Smoking prevalence, the number of population deaths avoided, and life-years gained are calculated for each policy scenario at the national and state levels. The model only considers direct individual benefits through reduced smoking and does not consider benefits through reduced exposure to secondhand smoke.

Ethics and dissemination

A web-based interface is being developed to integrate the results of the simulations into a format that allows the user to explore the projected effects of tobacco control policies in the USA. Usability testing is being conducted in which experts provide feedback on the interface. Development of this tool is under way, and a publicly accessible website is available at http://www.tobaccopolicyeffects.org.

Keywords: microsimulation, tobacco control policy, smoke-free air law, policy simulation, cigarette tax, minimum age of legal access to tobacco

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study develops a novel microsimulation method with a module that can be readily adapted to model the effects of different types of tobacco control policies.

The microsimulation model, the Smoking History Generator (SHG), advances existing tobacco policy modelling research by integrating detailed patterns of smoking by age, gender and birth cohort.

The SHG policy module reflects existing evidence and expert opinions on the effects of different tobacco control policies on smoking initiation, prevalence and cessation.

State-level estimates are limited by the fact that the model does not consider population heterogeneity across states as it is based on nationally representative data.

Estimated health outcomes are conservative as they do not include the benefits of reduced secondhand smoke exposure due to tobacco control policies.

Introduction

Over the last half-century, tobacco control efforts have led to an estimated 8 million fewer premature smoking-related deaths in the USA.1 Despite this incredible public health progress, smoking remains the leading cause of preventable death, and health gains from reduced smoking have not been distributed equally across the USA.2 Disparities in the smoking-related disease burden persist by sociodemographic factors and geographically by region.3 4

Large differences in the strength of tobacco control policies across states and localities contribute to these disparities: in New York, the price of a pack of cigarettes is currently $10.44, compared with $5.04 in Virginia.5 While states like California have had smoke-free air laws banning smoking in workplaces, restaurants and bars for years, other states like Oklahoma have no state-level policies prohibiting smoking in public places.6 7 Funding for state tobacco control programme also varies widely; Alaska commits more than $10 million in tobacco control expenditures, matching Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) state funding recommendations at more than 100%, whereas Ohio funds its programmes at 3% of CDC recommendations, totalling less than $4 million.8 These differences in state policies contribute to differences in smoking prevalence across states, which ranged from 9.1% (Utah) to 25.9% (Kentucky) in 2015.9

Computational models of smoking can provide estimates of the projected population health impact of policies and have been used by policymakers and health professionals to guide public health decision making.10 11 Several models of smoking have evaluated the impact of policies by applying macro-level changes to the population.12–17 A recent systematic review identified computational models of US-based tobacco control policies; most used population-level approaches (eg, system dynamics or compartmental models) when evaluating different types of policies.10

In contrast with previous work, we use a novel individual-level approach to evaluate the effects of tobacco policies through microsimulation. The advantage of this method is that it integrates detailed historical information about smoking patterns by birth cohort, age and gender. Furthermore, we develop an adaptable policy module that allows the microsimulation framework to readily integrate policy effects specific to each selected tobacco control policy. We describe an individual microsimulation model that simulates changes to smoking behaviour as a function of policy effects on the rates of smoking initiation and cessation by gender, age and birth cohort. We define policy effect sizes in relative terms as the change to the probability of smoking initiation (or cessation) due to the policy implementation at time t compared with the probability at time t−1. The model can be used to evaluate the effects of tobacco control policies within states and nationwide.

Policy modules have been added to the Cancer Intervention Surveillance Network (CISNET) Smoking History Generator (SHG).18 The SHG simulates individual life histories of US smoking and mortality and has been used in multiple, validated mathematical or statistical models to project long-term smoking and lung cancer outcomes.1 18–21 The SHG is calibrated to data from the National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS) (1964–2015) and has been used to estimate the impact of tobacco control policies on overall population health since 1965,1 and the impact of raising the minimum age of legal access (MLA) to tobacco.22

Our extension of the SHG incorporates policy effects on smoking initiation and cessation rates to project the potential public health impact of implementing tobacco control policies and programmes in the USA. We currently consider the effects of four types of tobacco control policies on population smoking and mortality at the state and national level: (1) cigarette taxes, (2) smoke-free air laws, (3) tobacco control programme expenditures and (4) raising the MLA to tobacco products. We describe a methodology for modelling the effects of these policies on future smoking prevalence and the number of total deaths avoided and life-years gained at the US state and national levels based on changes to individual smoking behaviour; estimates do not include benefits due to reduced secondhand smoke exposure. Finally, we are integrating the results of these simulations into an interactive web-based user interface that is accessible online at http://www.tobaccopolicyeffects.org. This work began in September 2015 and is expected to continue through August 2020.

Methods and analysis

The SHG

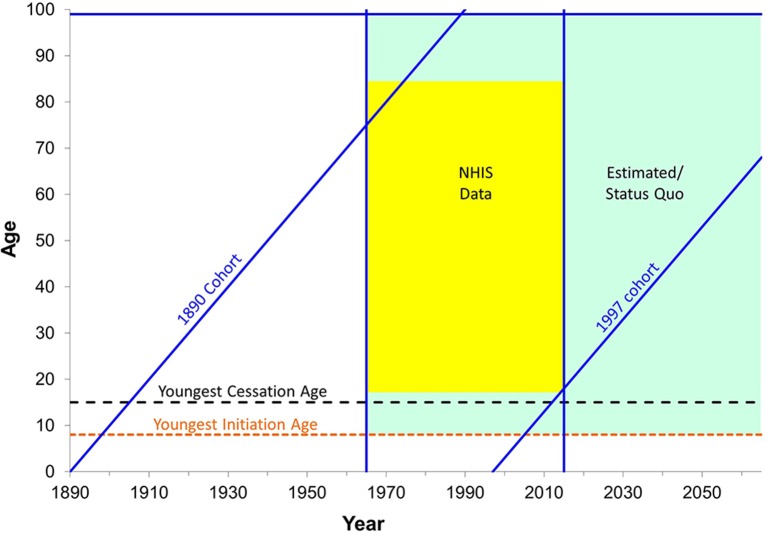

The CISNET SHG is a microsimulator that projects individual smoking initiation and cessation histories. Parameters for the microsimulator were derived by fitting a compartment model for smoking history in which individuals transition from never to current to former smokers based on initiation and cessation rates developed using the NHIS.21 These are cross-sectional data that necessitate correction for bias due to higher mortality among current and former smokers. Separate analyses were conducted for each gender. Data on smoking prevalence by age and survey year for this analysis was obtained from NHIS surveys 1965–1966, 1970, 1974, 1976–1980, 1983, 1985, 1987–1988, 1990–1995 and 1997–2015. A subset of these surveys provided retrospective histories of age at smoking initiation and cessation. Figure 1 shows years and ages covered by NHIS data in yellow, and time when histories were estimated using the fitted model in green.

Figure 1.

Population covered by the National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS) and the Smoking History Generator status quo scenario. Schematic diagram for data sources for Smoking History Generator parameters: years and ages with available NHIS data (yellow), and projection estimates (green), earliest (1890) and latest (1997) cohorts with available data, and youngest initiation (8 years) and cessation ages (15 years).

Ever smokers are those who smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Using retrospective histories for ever smokers, we estimated the probability that an individual initiates smoking at a given age, conditional on the individual being a never smoker at the beginning of that year. The initiation probabilities are calibrated by determining cross-sectional ever smoker prevalence trends by age within cohorts. To align cumulative initiation and cross-sectional estimates of ever smoker prevalence at a specified age, we obtained a multiplicative constant that was applied to the initiation probabilities at younger ages so that the two estimates coincide. The age used was 30 years or the age at the first survey, 1965, whichever was older.

We estimate conditional cessation probabilities based on the proportion of current smokers at a given age, who quit during that year, beginning at age 15 years. These were then used to generate the cumulative probability of quitting by age for each cohort. Cessation probabilities were held constant from age 85 years to 99+ years. Because smoking cessation is often not successful and shows a high rate of relapse in the first 2 years23–26 and since the SHG does not model relapse, we defined an individual as a former smoker if they had quit at least 2 years before the interview; otherwise, their observation was censored at the given age of quitting. Thus, current smokers in the model include those who have quit within the last 2 years, and the estimated cessation probabilities represent successful permanent smoking cessation. Note that smoking prevalence estimates generated by the SHG are thus higher than those reported by the NHIS due to the inclusion of recent quitters as current smokers. We validated the SHG smoking prevalence estimates against NHIS data using a revised definition for current smoking that includes those who quit less than 2 years ago. Figure 2 compares SHG smoking prevalence projections under the status quo scenario with NHIS using the 2-year quit definition.

Figure 2.

SHG adult smoking prevalence projections under the status quo scenario, 1965–2060. SHG and NHIS estimates shown above use an adjusted definition for smoking where ‘current smoking’ is defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, currently smoking every day or some days or having quit smoking less than 2 years ago. SHG, Smoking History Generator; NHIS, National Health Interview Surveys.

We use comprehensive historical data to reconstruct cohort patterns of smoking that have changed over time. The data used in the model to project future patterns initiation and cessation rates were generated using an age–period–cohort (APC) statistical model that specifically allows for age, period and cohort effects in recent years.

An APC model is used for each temporal effect. While interpretation of individual temporal effects are complicated by the well-known identifiability problem, we are only interested in fitted rates that result from the analysis, and these are unique and unaffected by this phenomenon.27 28 Each temporal effect was represented as a constrained natural spline,29 which is a semiparametric function for the additive effects of age, period and cohort.

For the baseline, or ‘status quo’, scenario, the SHG uses smoking history parameters estimated from the APC model for observed times and projects them forward holding corresponding APC parameters unchanged into the future. For instance, initiation probabilities for age 8 years and older used the estimated parameters from the model, holding values fixed at the estimated level for the 2015 period and the 1997 cohort (ie, individuals who were 18 at the last survey in 2015). Analogously, cessation probabilities for age 15 years and older used model parameters held at 2015 for period and 1985 for birth cohort (ie, individuals who were 30 at the last survey in 2015) for years not covered by NHIS. The implication of extrapolating the ‘status quo’ projections in this way is that cross-sectional estimates of current smoking prevalence will continue to decline until everyone born before 2015 is deceased (but this decline will slow down substantially as those born before 2015 represent ever smaller portions of the US population). Under this operational definition, status quo represents a future where the impact of tobacco control efforts on smoking initiation and cessation through 2015 will continue to accrue to future generations. It does not take into account the unrealised potential of current tobacco efforts or any potential back-sliding if efforts are not continued.

The SHG was developed in C++. A version of the SHG microsimulation model is available on request from the CISNET lung group. For requests, please send a message to shg-distrib@lung.cisnet-group.org.

The SHG policy module

We extend the SHG to directly evaluate the impact of policy changes on the baseline smoking initiation and cessation probabilities in separate modules for four policies: cigarette taxes, smoke-free air laws, tobacco control programme expenditures and raising the MLA to tobacco products. The SHG policy module does not consider the impact of these policies on secondhand smoke exposure.

The SHG policy modules first simulate smoking behaviour at the individual level, with annual smoking initiation, smoking cessation and death probabilities. The initiation and cessation rates are then modified to simulate policy scenarios. The modifiers (policy effects) are age specific and incorporate decay rates to account for the declining impact of a policy on initiation or cessation rates over time. These data at the individual level are subsequently aggregated to derive population current and former smoking prevalence as final outputs for each policy scenario (figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Smoking History Generator (SHG) policy module. The SHG policy module simulates the effects of tobacco control policies by modifying initiation and cessation probabilities at the individual level. Data can be aggregated to generate population level estimates.

The effects of each tobacco control policy are translated into modifiers for the SHG policy module based on existing literature and expert opinions. These effects depend on the current level of policies, with the magnitude of alternative policy effects scaled to incorporate the existing policy environment for each of the four policies. The web-based user interface provides baseline ‘status quo’ scenarios at the state level.

Smoking initiation and cessation rates under the baseline scenario are applied to hypothetical cohorts of 100 000 men and women born in the years 1910–2060 for a total of 30 million individuals simulated per policy scenario. The smoking initiation and cessation rates are age, gender and birth cohort specific and have been previously reported by CISNET.21 Under each tobacco control policy, individual smoking initiation and cessation probabilities are modified by age group, year of policy implementation and years since implementation. These modifiers adjust for differences in the policy’s effects across age groups and the level of existing policy coverage. The SHG policy module was developed in python, and the mortality and life year calculations were developed in R V.3.1.3.

Cigarette taxes

Raising cigarette taxes has been shown to be a highly effective tobacco control intervention; a large evidence-base demonstrates conclusively that increasing tax on cigarettes decreases cigarette consumption and reduces smoking.30–34 Taxes on cigarettes are generally per pack and can be levied at the local, state or federal levels. The current federal tax rate per pack is $1.71, and state tax rates vary from $4.35 (New York) to $0.17 (Missouri).5

The SHG policy module simulates the effects of increasing the price per pack of cigarettes through a one-time permanent tax. The model assumes that the tax is passed on directly to consumers as an increased price per pack of cigarettes. This assumption is based on prior research35 and has been used in previous models.36–40 It also assumes that the impact of the tax increase does not erode with inflation, which overestimates the effects for later years.

The effect of the cigarette tax on smoking behaviour depends on the price elasticities for cigarette initiation and cessation, measured as the per cent change in smoking initiation or cessation rates divided by the per cent change in price. The model also makes the conservative assumption of a constant price elasticity across price ranges, so effects may be even larger at higher prices. We developed initiation and cessation elasticities to conform (and match) to the more robust literature on smoking prevalence elasticities, rather than drawing from the smaller number of studies examining initiation and cessation elasticities per se.41 Larger price elasticities are used for younger ages, based on evidence that younger individuals are more responsive to price changes (table 1).42

Table 1.

Price elasticities by age group

| Age group (years) |

Cessation elasticity | Initiation elasticity |

| Ages 10–17 | 2.00 | −0.4 |

| Ages 18–24 | −0.3 | |

| Ages 25–34 | −0.2 | |

| Ages 35–64 | 0 | |

| Age 65+ | 0 |

Specifically, we apply higher price elasticities for lower age groups such that for each 10% increase in price, initiation rates are reduced by 4% for ages 10–17 years, by 3% for ages 18–24 years and by 2% for ages 25–34 years, with no impact on smoking initiation rates for those ages 35+ years. We also assume that a 10% increase in price translates into an initial 20% increase in smoking cessation rates for individuals at all ages. This effect on cessation decays with each year.

To model the effects of raising cigarette taxes, three inputs are required: the initial price per pack of cigarettes, the proposed tax increase and the year of policy implementation. The percent change in price is defined as the change in price divided by the average over the pre-tax and post-tax price of a pack of cigarettes. This assumption of a tax change relative to the average is based on calculations of the arc elasticity of demand.43

where K is the initial price per pack of cigarettes and T the proposed tax increase.

Price elasticity is assumed to be independent of the baseline price per pack of cigarettes. The % change in price is then multiplied by the corresponding price elasticities to calculate the policy effects on initiation and cessation in percentage terms relative to initial levels.

These effects are then translated into corresponding initiation and cessation modifiers for each age group. The effects of the tax on smoking initiation probabilities are assumed to remain constant over time. However, the effects of the tax on smoking cessation decay over time at rate d with the majority of quitting taking place in the first few years immediately following policy implementation.

For year n, the initiation and cessation modifiers are computed as follows:

where d is the decay rate and n 0 is the year when the policy was implemented.

These modifiers are then applied to the probabilities of smoking initiation and cessation for each individual in the SHG microsimulation. The SHG policy module thus adjusts for differences in tax effects by age, the relative change in price compared with the initial price of a pack of cigarettes and years since the tax increase went into effect. A 0.2 decay rate was estimated during model calibration, so that in conjunction with the SHG cessation probabilities, the model reproduced reported policy effects on smoking prevalence over time. This reflected the immediate impact with continued effects over time, as indicated by studies of price increases on smoking prevalence.44 These time patterns are also consistent with results from the validated SimSmoke model.

Smoke-free air laws

Smoke-free air policies prohibit smoking in designated areas and usually are applied to indoor settings. These laws are typically applied to three types of venues—workplaces (private and public), restaurants and bars—and are implemented at the state and local levels. Currently, 25 states have comprehensive smoke-free air laws that prohibit smoking in non-hospitality work sites, restaurants and bars.7 We do not consider smoke-free air laws in other settings such as public transit, shopping areas or parks.

Research on smoke-free air laws shows that they are effective in reducing smoking prevalence45 and that they increase cessation rates.46–48 We assume that approximately 66% of reductions associated with comprehensive smoke-free air laws can be attributed to smoking bans applied to workplaces. Based on the evidence,49 50 it is estimated that comprehensive smoking bans (complete bans in workplaces, restaurants and bars) reduce smoking prevalence by 9% within 5 years, with the majority of this effect due to workplace smoking bans (6% reduction attributed to worksites, 2% attributed to restaurants and 1% attributed to bars). We assume then different relative effects of bans on smoking for workplaces , restaurants and bars . These relative effects were reviewed by an expert panel as part of an extensive assessment of the literature conducted for a previously validated model of smoke-free air laws.50–52

For smoke-free air laws, we calibrated the policy effects to reach desired changes to smoking prevalence based on existing policy evaluation literature. The SHG policy module was calibrated such that complete smoking bans in workplaces, restaurants and bars reduced adult smoking prevalence by 9%–10% within 5 years for ages <65 years and by 5% for ages 65+ years, as this population is less likely to be in the workforce and therefore less affected by smoking bans in workplaces. Age-specific scaling factors were used to adjust the effects by age. These calibration targets were achieved when the policy reduced initiation rates by 10% and increased cessation rates by 50% . Thus, these are the assumed policy effects of a comprehensive smoking ban assuming no existing smoke-free air law coverage.

The effects of a given smoke-free air law are moderated based on the per cent of workplaces , restaurants and bars that are already covered by existing smoke-free air laws and which venues the policy is applied to .

Inputs for the specific venues of the smoke-free air law , the level of existing smoke-free air law coverage for that venue type , the effect sizes for the specific venues and the year of policy implementation are used to model the effects of a given smoke-free air policy and translate these into modified initiation and cessation probabilities. To model the effect of smoke-free air laws in the SHG policy module, for year n and age a, the initiation and cessation modifiers are computed as follows:

where are 0.10, 0.50 and 0.20, respectively, and is the year when the policy was implemented.

This process applies the appropriate initiation and cessation probabilities for each individual simulated adjusting for differences in smoke-free air policy effects by age (a), years since policy implementation the venues the policy is applied to and their relative contributions () and the existing smoke-free air policy environment .

As with cigarette taxes, it is assumed that smoke-free air laws decrease initiation rates for all individuals in the first year implemented and that these effects on initiation remain constant going into the future. The effects of smoke-free air laws on cessation decay over time at rate d, as those who are most prone to quit in response to the policy change have already done so in the early years. A 0.2 decay rate was also calibrated to reflect evidence of the effects of this policy on smoking prevalence over time.

Tobacco control programme expenditures

Comprehensive tobacco control programmes are coordinated interventions to reduce tobacco use, increase tobacco cessation, reduce secondhand smoke exposure and prevent youth smoking initiation.53 These programmes can be implemented at the local, state or national levels and combine multiple components including: mass-reach health communication interventions, cessation interventions, surveillance and evaluation and state and community interventions (eg, school-based programmes). Prior research has found investing in these programmes to have positive impact on smoking-related outcomes.54–56 The CDC provides recommended annual levels of state investment in comprehensive tobacco control programmes to all 50 states and Washington, DC.57 We operationalise comprehensive tobacco control programmes as a policy intervention based on the amount of expenditures invested relative to the level of funding recommended by the CDC. We assume that the policy level of funding is sustained in the future.

Figure 4 presents estimated policy effect sizes, or the relative change to the probability of smoking initiation or cessation due to a policy, by the level of tobacco control programme expenditures. Based on a review of 56 studies58 and a recent analysis on the impact of comprehensive programmes,59 we assume that a change in investment in comprehensive tobacco control spending from 0% to 100% of CDC recommendations translates into an approximate 10% decrease to initiation probabilities and a 12.5% increase to cessation probabilities applied to all ages.

Figure 4.

Effects of increasing tobacco control programme expenditures. Policy effects represent the relative change to the probability of smoking initiation or cessation due to an increase in the level of tobacco control programme expenditures. CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We also assume, based on our interpretation of the literature and feedback from two tobacco control experts, increasing and then decreasing returns for the effects as the level of funding shifts from 0% to 100% of recommendations. This shape of the curve is also consistent with prior work on the effects of mass media campaigns,60 which are a major component of such expenditures. In order for tobacco control expenditures to be effective, it is assumed that they must reach an initial level before the returns on that investment begin to increase. Then the magnitude of effects for a given relative change in funding becomes larger, as shown by the steeper slope of the curve in figure 4, before reaching higher levels where the curve flattens and the change in effect size diminishes.

For example, raising the level of expenditures from 10% () to 50% of CDC recommendations, where =7.1% and =0.7%, translates into a 6.4% increase in cessation probabilities. Likewise, this increase in tobacco control programme expenditures corresponds to a 7.9% decrease in initiation probabilities (9.0%–1.1%).

As with the previous two policies, these effects are implemented through initiation and cessation modifiers. We assume the same decay rate d as for smoke-free air laws and for tax increases. For year n, the initiation and cessation modifiers are computed as follows:

Note that and represent the proposed level of expenditure investment at year n and the initial level of expenditure investment when the policy was implemented , respectively.

Minimum age of legal access

The MLA to tobacco products is set by local, state and federal laws to prevent individuals under a specified age from legally purchasing tobacco products. At the federal level, the MLA is 18 years; however, some states have raised the MLA to age 19 years (Alaska, Alabama and Utah) and 21 years (Hawaii, California, New Jersey, Maine and Oregon).

Research shows that raising the MLA to 21 years reduces youth smoking.61 Evidence on policies restricting youth access to cigarettes and alcohol strongly indicates that increasing enforcement of the MLA would reduce smoking.22 Regarding raising the age to 21 years, a recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report concluded that ‘increasing the MLA to tobacco products will likely prevent or delay initiation of tobacco use by adolescents and young adults’.22 The SHG policy module uses effect sizes that were developed by the IOM Committee to evaluate the impact of raising the MLA to ages 19, 21 or 25 years (table 2).22

Table 2.

Effects of raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products

| Reduction in initiation by age group (years) | Effect of raising the MLA | ||

| E19 (%) | E21 (%) | E25 (%) | |

| 0–14 | 5 | 15 | 15 |

| 15–17 | 10 | 25 | 30 |

| 18 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| 19–20 | 0 | 15 | 20 |

| 21–25 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

The SHG policy module assumes that raising the MLA to tobacco products only impacts smoking initiation rates for youth and young adults, with no impact on smoking cessation behaviour. These effects on initiation are scaled down based on the level of existing MLA coverage in a given state or region. Four inputs to the model are required: the proposed MLA (19, 21 or 25), and the per cent of the population already covered by local or state MLA laws at age 19 , 21 and 25 . This approach accounts for different MLA effects by age group and the existing MLA policy environment. The effect for an MLA policy at 19 , 21 and 25 is calculated for each simulated individual’s age, a, where a=0, 1,…, 25, as follows:

Note that is the effect of raising the MLA to the hypothesised age ‘i’ on reduction in smoking initiation among people whose age are a.

For year n and age a, the initiation modifier is computed for a given MLA policy as follows:

Model outcomes

Projected smoking prevalence and the number of population deaths avoided and life years gained are calculated for each simulated policy scenario. The number of deaths avoided is calculated by subtracting the total number of smoking-attributable deaths under the policy scenario from the total deaths under the baseline scenario. Using the same methodology previously described by the IOM committee on raising the MLA to tobacco,22 total smoking-attributable deaths are calculated by first multiplying the prevalence of current smokers and former smokers by the corresponding population sizes (P) for each age group (a) and gender (g), and then again by the difference in mortality rates between current or former smokers and never smokers ():

For each smoking-attributable death of a current or former smoker at a given age, the number of life years lost due to smoking is equivalent to the remaining expected years of life for never smokers at that age (). Thus, by applying the never smoker life expectancy (in years) to the number of smoking-attributable deaths at a given age, the total years of life lost () in the population can be calculated by summing this value across all ages and genders.

Life years gained are calculated by subtracting the total years of life lost due to smoking under the policy scenario from the total under the baseline scenario.

The estimates for health outcomes do not include benefits attributable to reductions in secondhand smoke exposure, which is particularly important for smoke-free air policies. The CISNET SHG was developed using national-level data, and it currently does not account for state population heterogeneity or differences by geographic region. To approximate the policy effects for state populations, we adjust the SHG policy module results generated for the US population to the populations in each US state and Washington, DC. This is accomplished by taking the resulting national-level smoking prevalence, deaths avoided and life years gained under specific scenarios and directly scaling these data to the projected population size and smoking prevalence of each US state and Washington, DC. For example, if a state’s smoking prevalence is 10% higher than the smoking prevalence for the US population, all projected prevalence and policy estimates for that state are inflated by 10%. Likewise, the calculations of the smoking attributable deaths and life years gained are done using state-specific projected populations by gender and age. State population sizes and smoking prevalence are derived from Census Bureau population estimates in 2015 and the 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, respectively,62 and projected state population sizes for 2016–2060 are obtained by applying the census national projected population changes by age and gender to the 2015 state populations.

Web-based user interface

We are developing a web-based interface that allows the user to explore the model outcomes generated for each policy. To ensure that the website will be useful to its target audience and to avoid misinterpretation of the results, we conducted three rounds of usability testing of a working prototype of the site in October 2016, February 2017 and August 2017. Following each round of testing, we incorporated changes based on our findings, integrating user feedback. We are continuing to resolve issues with user comprehension to make entering model inputs more intuitive.

A key finding that emerged during usability testing of the interface was that data needed to be presented at the state level, since most policy decisions are made by or within states. Because the underlying data are from the NHIS, which is designed to provide statistics at the national level, we developed strategies for scaling each measure, as described in the section above.

The web-based interface will allow the user to select either one of 50 states or Washington DC, or select an average representing the USA as a whole. Once one of these is selected, the interface self-populates with default settings for the policy environment for their selected state based on recent datasets from the CDC, National Cancer Institute and advocacy groups. These prepopulated values may be adjusted by the user. The user is then able to examine policy outcomes under a user-determined policy scenario. The range of user-determined policy inputs are presented in table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of user inputs for tobacco control policy scenarios

| Tobacco control policy | User inputs | ||

| Baseline scenario | Policy scenario | Policy start year | |

| Cigarette taxes | Initial price per pack of cigarettes (initial price): $4.00–$10.00 | Tax increase (tax): $0.50–$6.00 | 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020 |

| Smoke-free air laws | Percent of existing smoke-free air law coverage in workplaces, restaurants, bars (paci): 0%–100% | 100% coverage smoke-free air law applied to workplaces, restaurants and/or bars (Ii) | |

| Tobacco control programme expenditures | Initial level of expenditures as % of CDC recommendation (F0): 0%–100% | Policy level of expenditures as 100% of CDC recommendation (Fn) | |

| Minimum age of legal access (MLA) | Percent of population already covered by MLA at age 19 years or age 21 years (pac19 and pac21): 0%–100% | Raise MLA to age 19, 21 or 25 years (MLA19, 21 or 25) | |

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

State-level data on existing tobacco control policies for smoke-free air laws in workplaces, restaurants and bars6; cigarette prices per pack,5 level of tobacco control expenditures8 57 and the MLA to tobacco22 63 will be compiled and integrated into the interface as default settings. For smoke-free policies in workplaces, we use state-level data from the 2014-2015 Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey on the per cent of the working population reporting that their workplace is smoke free (includes policies implemented by private firms). This is because implementing a state law to ban smoking in workplaces would have a limited impact in private workplaces that already have existing smoke-free policies.

Once the user selects the relevant inputs for their policy scenario, graphs from the pregenerated SHG policy module simulations are displayed. These will include comparisons of the baseline scenario with the policy scenario for each outcome: smoking prevalence (by age group, gender and birth cohort), number of population deaths avoided by gender and life years gained by gender. These estimates will be conservative as they do not include benefits due to reduced secondhand smoke exposure.

The interface uses previously generated results using prespecified input value combinations for each of the policies. Anticipating input parameter requirements for the target audience and pregenerating results for each combination of input values is a novel approach and has significant benefits. Users can obtain results based on different input assumptions instantaneously rather than rely on a lengthy wait and often costly simulation process to be prepared and executed. The availability of instantaneous visualisation of the outcomes facilitates comparisons between states and data exploration for a given state.

A choropleth map will be shown for each policy to further assist users in comparing outcomes between states. The colour scheme for each map is derived from the potential impact that the policy would have for a given state based on what is known about the initial conditions. For each policy, users can easily determine which states have the most potential impact if they were to apply the policy relative to other states. An example of the map for the smoke-free air laws policy is shown in figure 5. In this case, states with darker colours have a lower current smoke-free air law coverage and thus have the most potential to benefit from a smoke-free air law that would increase the coverage to 100%. Colours correspond to the weighted average across workplaces , restaurants and bars .

Figure 5.

Choropleth map of policy conditions across US states. Colours represent existing smoke-free air law coverage using a weighted average of the per cent of the population covered by smoke-free workplaces, restaurants and bars. Light-coloured states have higher existing coverage, while darker coloured states have lower levels of smoke-free air law coverage. Policy data are from the Americans for Non-Smokers Rights Foundation and the NCI and CDC State Cancer Profiles.6 7 CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCI, National Cancer Institute.

Future developments

We plan to conduct sensitivity analyses to assess the extent to which parameter uncertainty may influence the model results. Table 4 summarises model estimates, assumptions and limitations for each tobacco control policy as previously described. For each parameter (eg, policy decay rate and price elasticities), we will develop plausible ranges for the numerical estimate. Then for each simulated tobacco control policy, we will use standard techniques, such as latin hypercube or joint multivariate methods, to jointly sample from within those sets of parameter ranges during simulation. By varying all the parameters simultaneously for a given scenario, we will produce a range of possible outcomes and quantify the degree of uncertainty in the modelling. This additional analysis ensures a more rigorous assessment of the model assumptions and their implications for policies.

Table 4.

Summary of model estimates and assumptions

| Tobacco control policy | Estimates | Assumptions | Limitations |

| Cigarette taxes |

|

|

|

| Smoke-free air laws |

|

|

|

| Tobacco control programme expenditures |

|

|

|

| Minimum age of legal access (MLA) |

|

|

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We also plan to extend this model to consider additional health outcomes and different subpopulations across the USA. As one example, the current model simulates the impact of policies on the number of deaths due to any cause; we will eventually evaluate the impact of policies on deaths due to lung cancer specifically. Future work may also include considering the impact of policies on morbidity in addition to mortality.

Patterns of smoking are known to differ by geographic region and sociodemographic characteristics, with important disparities in smoking initiation, cessation and prevalence across the population. Although the current model is based on national-level data, and a rescaling approach based on state-level population and smoking prevalence, we will use additional data to develop state-specific smoking parameters in future work. We also plan to extend the underlying SHG to simulate differences by level of educational attainment.

The input parameters and uncertainty estimates presented here may change based on future feedback on the model and its results. In subsequent peer-reviewed publications of the model’s findings, we will note any deviations from this protocol.

Ethics and dissemination

Results from the SHG policy module will be released as a publicly accessible website to support public health decision making. A separate manuscript outlining the findings from this work will be published and disseminated in an open-access publication following release of the website.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Stephanie Land and Carolyn Reyes-Guzman for their critical input on drafts of this protocol manuscript. We would also like to thank our reviewers for their helpful feedback and suggestions for improvement.

Footnotes

Contributors: JT drafted the manuscript. JT, RM and DTL operationalised the SHG policy module for each of the policies. TRH, JJ, EJF and RM contributed to the development of the SHG and status quo projections. JC and TH developed the web-based user interface with input from RM, JT and DTL. SG conducted usability testing. All authors were involved in manuscript revisions and approved the final version of the protocol.

Funding: This work is funded by NCI grant U01CA199284-01.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was submitted to the Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB-HSBS) at the University of Michigan and received an exemption due to the absence of risk to the human subjects.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Holford TR, Meza R, Warner KE, et al. Tobacco control and the reduction in smoking-related premature deaths in the United States, 1964-2012. JAMA 2014;311:164–71. 10.1001/jama.2013.285112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion,. BRFSS Prevalence & Trends Data [online]: Division of Population Health, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/ (accessed 5 Apr 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jamal A, King BA, Neff LJ, et al. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2005-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1205–11. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6544a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. State cigarette tax rates & rank, date of last increase, annual pack sales & revenues, and related data. 2017. http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/research/factsheets/pdf/0099.pdf (accessed 5 Sept 2017).

- 6. National Cancer Institute, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State cancer profiles. 2017. https://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/risk/ (accessed 1 Jul 2017).

- 7. Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation. Smokefree lists, maps, and data. 2017. http://no-smoke.org/goingsmokefree.php?id=519 (accessed 10 Aug 2017).

- 8. Huang J, Walton K, Gerzoff RB, et al. State tobacco control program spending–United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:673–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current cigarette use among adults (behavior risk factor surveillance system). 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/cigaretteuseadult.html (accessed 15 Apr 2014).

- 10. Feirman SP, Glasser AM, Rose S, et al. Computational models used to assess us tobacco control policies. Nicotine Tob Res 2017;19:1257–67. 10.1093/ntr/ntx017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feirman SP, Donaldson E, Glasser AM, et al. Mathematical modeling in tobacco control research: initial results from a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:229–42. 10.1093/ntr/ntv104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mendez D, Warner KE, Courant PN. Has smoking cessation ceased? Expected trends in the prevalence of smoking in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 1998;148:249–58. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mendez D, Warner KE. Adult cigarette smoking prevalence: declining as expected (not as desired). Am J Public Health 2004;94:251–2. 10.2105/AJPH.94.2.251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Warner KE, Méndez D. Accuracy and importance of projections from a dynamic simulation model of smoking prevalence in the United States. Am J Public Health 2012;102:2045–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Levy DT, Mabry PL, Graham AL, et al. Reaching Healthy People 2010 by 2013: A SimSmoke simulation. Am J Prev Med 2010;38(3 Suppl):S373–81. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levy DT, Pearson JL, Villanti AC, et al. Modeling the future effects of a menthol ban on smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths in the United States. Am J Public Health 2011;101:1236–40. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levy DT, Boyle RG, Abrams DB. The role of public policies in reducing smoking: the Minnesota SimSmoke tobacco policy model. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:S179–86. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jeon J, Meza R, Krapcho M, et al. Chapter 5: Actual and counterfactual smoking prevalence rates in the U.S. population via microsimulation. Risk Anal 2012;32(Suppl 1):S51–S68. 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01775.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moolgavkar SH, Holford TR, Levy DT, et al. Impact of reduced tobacco smoking on lung cancer mortality in the United States during 1975-2000. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:541–8. 10.1093/jnci/djs136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Koning HJ, Meza R, Plevritis SK, et al. Benefits and harms of computed tomography lung cancer screening strategies: a comparative modeling study for the U.S. preventive services task force. Annals of Internal Medicine 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Holford TR, Levy DT, McKay LA, et al. Patterns of birth cohort-specific smoking histories, 1965-2009. Am J Prev Med 2014;46:e31–7. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. IOM (Institute of Medicine). Health implications of raising the minimum age for purchasing tobacco products. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krall EA, Garvey AJ, Garcia RI. Smoking relapse after 2 years of abstinence: findings from the VA Normative Aging Study. Nicotine Tob Res 2002;4:95–100. 10.1080/14622200110098428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hughes JR, Peters EN, Naud S. Relapse to smoking after 1 year of abstinence: a meta-analysis. Addict Behav 2008;33:1516–20. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hawkins J, Hollingworth W, Campbell R. Long-term smoking relapse: a study using the british household panel survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:1228–35. 10.1093/ntr/ntq175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 2004;99:29–38. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holford TR. The estimation of age, period and cohort effects for vital rates. Biometrics 1983;39:311–24. 10.2307/2531004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holford TR. Understanding the effects of age, period, and cohort on incidence and mortality rates. Annu Rev Public Health 1991;12:425–57. 10.1146/annurev.pu.12.050191.002233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med 1989;8:551–61. 10.1002/sim.4780080504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith K, Gilmore A, Chaloupka F, et al. IARC handbooks of cancer prevention: tobacco control volume 14 effectiveness of price and tax policies for control of tobacco. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2011:31–90. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Contreary KA, Chattopadhyay SK, Hopkins DP, et al. Economic impact of tobacco price increases through taxation: a community guide systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2015;49:800–8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chaloupka FJ, Straif K, Leon ME. Working Group, International Agency for Research on Cancer. Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tob Control 2011;20:235–8. 10.1136/tc.2010.039982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chaloupka FJ, Yurekli A, Fong GT. Tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. Tob Control 2012;21:172–80. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Warner KE. Death and taxes: using the latter to reduce the former. Tob Control 2014;23(Suppl 1):i4–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sung Hai-Yen, Hu Teh-Wei, Keeler TE. Cigarette taxation and demand: an empirical model. Contemp Econ Policy 1994;12:91–100. 10.1111/j.1465-7287.1994.tb00437.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ahmad S. Increasing excise taxes on cigarettes in California: a dynamic simulation of health and economic impacts. Prev Med 2005;41:276–83. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ahmad S, Franz GA. Raising taxes to reduce smoking prevalence in the US: a simulation of the anticipated health and economic impacts. Public Health 2008;122:3–10. 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Emery S, Ake CF, Navarro AM, et al. Simulated effect of tobacco tax variation on Latino health in California. Am J Prev Med 2001;21:278–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kaplan RM, Ake CF, Emery SL, et al. Simulated effect of tobacco tax variation on population health in California. Am J Public Health 2001;91:239–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Levy DT, Friend K. Examining the effects of tobacco treatment policies on smoking rates and smoking related deaths using the SimSmoke computer simulation model. Tob Control 2002;11:47–54. 10.1136/tc.11.1.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. The Community Preventive Services Task Force. Reducing Tobacco Use and Secondhand Smoke Exposure: Interventions to Increase the Unit Price for Tobacco Products. 2014. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/tobacco-use-and-secondhand-smoke-exposure-interventions-increase-unit-price-tobacco (accessed 29 May 2017).

- 42. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Allen RGD. The concept of arc elasticity of demand: I. Rev Econ Stud 1934;1:226–9. 10.2307/2967486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention, Tobacco Control, Vol 14: Effectiveness of Tax and Price Policies for Tobacco Control. Lyon, France 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hopkins DP, Razi S, Leeks KD et al. Smokefree policies to reduce tobacco use. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:S275–89. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Burns D, Anderson C, Johnson M. Cessation and cessation measures among daily adult smokers: national-and state-specifıc data. Population Based Smoking Cessation Monograph No 12. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health. National Cancer Institute, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Farkas AJ, Gilpin EA, Distefan JM, et al. The effects of household and workplace smoking restrictions on quitting behaviours. Tob Control 1999;8:261–5. 10.1136/tc.8.3.261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Glasgow RE, Cummings KM, Hyland A. Relationship of worksite smoking policy to changes in employee tobacco use: findings from COMMIT. Community Intervention Trial for Smoking Cessation. Tob Control 1997;6(suppl 2):S44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ohsfeldt RL, Boyle RG, Capilouto EI. Tobacco taxes, smoking restrictions, and tobacco use: National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Levy DT, Friend K, Polishchuk E. Effect of clean indoor air laws on smokers: the clean air module of the SimSmoke computer simulation model. Tob Control 2001;10:345–51. 10.1136/tc.10.4.345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Levy DT, Meza R, Zhang Y, et al. Gauging the effect of U.S. tobacco control policies from 1965 through 2014 using simsmoke. Am J Prev Med 2016;50:535–42. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Levy DT, Friend KB. The effects of clean indoor air laws: what do we know and what do we need to know? Health Educ Res 2003;18:592–609. 10.1093/her/cyf045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. The Community Preventive Services Task Force. Reducing tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure: comprehensive tobacco control programs. 2014. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/tobacco-use-and-secondhand-smoke-exposure-comprehensive-tobacco-control-programs (accessed 29 May 2017).

- 54. Farrelly MC, Pechacek TF, Chaloupka FJ. The impact of tobacco control program expenditures on aggregate cigarette sales: 1981-2000. J Health Econ 2003;22:843–59. 10.1016/S0167-6296(03)00057-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tauras JA, Chaloupka FJ, Farrelly MC, et al. State tobacco control spending and youth smoking. Am J Public Health 2005;95:338–44. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.039727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Farrelly MC, Pechacek TF, Thomas KY, et al. The impact of tobacco control programs on adult smoking. Am J Public Health 2008;98:304–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.106377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs—2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guide to Community Preventive Services. Reducing tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure: smoke-free policies. Atlanta: CDC, 2016. http://www.thecommunityguide.org/tobacco/smokefreepolicies.html (accessed 14 Jul 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rhoads JK. The effect of comprehensive state tobacco control programs on adult cigarette smoking. J Health Econ 2012;31:393–405. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Levy DT, Friend K. A computer simulation model of mass media interventions directed at tobacco use. Prev Med 2001;32:284–94. 10.1006/pmed.2000.0808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kessel Schneider S, Buka SL, Dash K, et al. Community reductions in youth smoking after raising the minimum tobacco sales age to 21. Tob Control 2016;25:355–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey data. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Preventing Tobacco Addiction Foundation. Tobacco twenty-one state by state: list of all tobacco 21 cities. 2017. http://tobacco21.org/state-by-state/ (accessed March 1 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.