Abstract

Adiponectin exerts renoprotective effects against diabetic nephropathy (DN) by activating the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/peroxisome proliferative-activated receptor–α (PPARα) pathway through adiponectin receptors (AdipoRs). AdipoRon is an orally active synthetic adiponectin receptor agonist. We investigated the expression of AdipoRs and the associated intracellular pathways in 27 patients with type 2 diabetes and examined the effects of AdipoRon on DN development in male C57BLKS/J db/db mice, glomerular endothelial cells (GECs), and podocytes. The extent of glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis correlated with renal function deterioration in human kidneys. Expression of AdipoR1, AdipoR2, and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase–β (CaMKKβ) and numbers of phosphorylated liver kinase B1 (LKB1)– and AMPK-positive cells significantly decreased in the glomeruli of early stage human DN. AdipoRon treatment restored diabetes-induced renal alterations in db/db mice. AdipoRon exerted renoprotective effects by directly activating intrarenal AdipoR1 and AdipoR2, which increased CaMKKβ, phosphorylated Ser431LKB1, phosphorylated Thr172AMPK, and PPARα expression independently of the systemic effects of adiponectin. AdipoRon-induced improvement in diabetes-induced oxidative stress and inhibition of apoptosis in the kidneys ameliorated relevant intracellular pathways associated with lipid accumulation and endothelial dysfunction. In high-glucose–treated human GECs and murine podocytes, AdipoRon increased intracellular Ca2+ levels that activated a CaMKKβ/phosphorylated Ser431LKB1/phosphorylated Thr172AMPK/PPARα pathway and downstream signaling, thus decreasing high-glucose–induced oxidative stress and apoptosis and improving endothelial dysfunction. AdipoRon further produced cardioprotective effects through the same pathway demonstrated in the kidney. Our results show that AdipoRon ameliorates GEC and podocyte injury by activating the intracellular Ca2+/LKB1-AMPK/PPARα pathway, suggesting its efficacy for treating type 2 diabetes–associated DN.

Keywords: AdipoRon, Lipotoxicity, diabetic nephropathy, oxidative stress

Although diabetic nephropathy (DN) is traditionally characterized by hyperglycemia-induced metabolic and hemodynamic changes, accumulating evidences suggest that derangements in lipid metabolism play a crucial role in DN development and progression. Accumulation of free fatty acids, which are otherwise used as an energy source, in tubular epithelial cells of diabetic kidneys indicates a state of energy surplus.1 This state of energy surplus (referred to as lipotoxicity) is characterized by the deposition of fatty acid metabolites such as diacylglycerols and ceramides in nonadipose organs and leads to toxicity and cell death.2 Although mainstream research indicates that slowdown of fatty acid β-oxidation leads to the accumulation of different lipid products,3 emerging evidence indicates that rapid but incomplete β-oxidation in the nonadipose tissue and by-products of oxidative stress promote the formation of toxic lipid intermediates.4

Adiponectin is one of the numerous adipokines secreted by adipocytes.5 It exerts favorable effects in the milieu of metabolic syndrome through anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, and antioxidant effects.6 Adiponectin mediates fatty acid metabolism by inducing AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation and increasing peroxisome proliferative-activated receptor–α (PPARα) expression, which in turn upregulate the expression of acyl CoA oxidase and uncoupling proteins involved in energy consumption.7,8 Low circulating adiponectin levels in obese patients with a risk of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease9 and increased adiponectin expression in state of albuminuria indicate the protective and compensatory role of adiponectin10 to mitigate further renal injury against the development of overt nephropathy.5,11 These beneficial effects of adiponectin have prompted research on drugs that mimic adiponectin, yet this manner of increasing the level of circulating adiponectin is not a panacea. Moreover, adiponectin overexpression is associated with adverse effects such as reduced bone density, left ventricular hypertrophy, weight gain, tumor growth, and infertility.12–14 Therefore, there is a need to develop a novel agent that could deliver the favorable effects of adiponectin but not the detrimental pitfalls due to adiponectin excess.

AdipoRon is an orally active synthetic adiponectin receptor agonist developed by Okada-Iwabu et al.15 In db/db mice, AdipoRon binds to AdipoRs AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 to activate AMPK and PPARα, respectively, and induces such prometabolic effects as improved insulin sensitivity, weight neutrality, and expanded life span.15 Diminished adiponectin-associated metabolic effect in AdipoR1-/AdipoR2-knockout mice and restoration of obesity-induced metabolic alterations in high-fat-diet–fed mice by AdipoRon administration with implication on fatty acid combustion suggest that AdipoRon is a promising agent for treating type 2 diabetes.15,16 This instigated us to investigate the favorable effects of AdipoRon against DN in db/db mice, human glomerular endothelial cells (GECs), and murine podocytes. In addition, we examined renal AdipoR1/AdipoR2 expression and CaMKKβ/phosphorylated Ser431LKB1/phosphorylated Thr172AMPK pathway activation in type 2 diabetes and hypothesized that AdipoRon treatment ameliorated lipotoxicity and oxidative stress by activating the AMPK/PPARα pathway by increasing AdipoR1/AdipoR2 expression.

Results

Human Diabetic Kidneys Show Decreased Intraglomerular AdipoR1/AdipoR2 Expression and Decreased CaMKKβ/Phosphorylated Ser431LKB1/Phosphorylated Thr172AMPK/PPARα Pathway

The patient group included 27 patients with biopsy-proven DN. Clinical characteristics of these patients are shown (Supplemental Table 1). Nondiabetic subjects included healthy controls (n=6) with minor urinary abnormalities. In diabetes, the extent of glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis markedly increased with renal function deterioration (Figure 1, A and B). Immunofluorescence analysis showed that AdipoR1/AdipoR2, CaMKKβ, and nephrin expression and phosphorylated AMPK- and phosphorylated LKB1-positive cell number significantly decreased in the glomerulus of human diabetic kidneys compared with that of nondiabetic control kidneys even in the earliest CKD stage. There were no significant differences in the expression of AdipoRs and their relevant downstream molecules with increasing stages of CKD (Figure 1, C–L) and in those with or without angiotensin II receptor blocker use in the kidneys (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Human diabetic kidneys show characteristic diabetic alterations in line with decreased expression of intraglomerular AdipoRs and relevant molecules according to CKD stages. Representative sections stained with (A and B) PAS reagent, (C–L) immunofluorescence staining, and quantitative analyses of AdipoR1, AdipoR2, CaMKKβ, phosphorylated Ser431LKB1, phosphorylated Thr172AMPK, and nephrin levels in the human diabetic and nondiabetic kidneys according to CKD stages. *P<0.05; #P<0.001 compared with other groups.

AdipoRon Improves Renal Function without Affecting Serum Adiponectin and Glucose Levels in db/db Mice

Serum adiponectin level was higher in nondiabetic mice than in diabetic mice. AdipoRon treatment did not affect body weight or food intake. Moreover, it did not affect plasma glucose, HbA1c, and serum creatinine levels in both nondiabetic and diabetic mice. There were no differences in systolic BP among study groups and creatinine clearance decreased in db/db mice treated with AdipoRon. Moreover, albuminuria, urinary nitric oxide metabolites (NOx), and homeostatic model assessment–insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) index improved in db/db mice treated with AdipoRon compared with those in db/db control and in diabetic mice before the treatment (Table 1). These results suggest that AdipoRon ameliorates metabolic and renal function parameters independently of serum adiponectin and glucose levels.

Table 1.

Biochemical and physical characteristics of mice in the four groups before and after 4 weeks of AdipoRon treatment

| Characteristics | db/m Cont | db/m AdipoRon | db/db Cont | db/db AdipoRon | 16 w db/db Cont |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 36.2±1.7 | 37.2±1.8 | 53.0±7.3a | 51.1±4.8a | 49.9±3.4a |

| Kidney weight, g | 0.20±0.04 | 0.21±0.03 | 0.21±0.04 | 0.21±0.01 | 0.22±0.01 |

| Heart weight, g | 0.18±0.02 | 0.18±0.02 | 0.18±0.04 | 0.17±0.02 | 0.17±0.03 |

| FBS, mg/dl | 152±14 | 138±7 | 534±89a | 532±93a | 640±150a |

| HbA1c, % | 4.0±0.2 | 3.9±0.2 | 10.5±0.49a | 11.5±0.8a | 8.8±0.7b |

| HOMAIR | 0.06±0.01 | 0.06±0.01 | 2.37±0.02a | 0.21±0.01b | 2.11±0.11a |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.70±0.41 | 2.65±0.51 | 3.51±0.42c | 3.39±0.55c | 3.80±0.50c |

| Triacylglycerols, mmol/L | 1.21±0.21 | 1.32±0.19 | 2.18±0.33a | 1.60±0.22c | 1.96±0.29a |

| Nonesterified fatty acid, mmol/L | 0.62±0.22 | 0.67±0.19 | 1.42±0.20c | 1.21±0.15c | 1.41±0.21c |

| 24-h albuminuria, µg/d | 10.0±2.0 | 8.2±2.8 | 223.0±51.9a | 100.0±18.8b | 163.2±30.3a |

| Urine volume, ml | 0.8±0.2 | 1.0±0.2 | 14.5±4.5a | 10.3±3.4a,c | 11.4±4.3a,c |

| Serum Cr, µmol/L | 17.1±3.1 | 17.3±1.7 | 19.3±3.7 | 17.5±3.9 | 18.3±3.1 |

| Ccr, ml/min | 0.36±0.11 | 0.32±0.23 | 1.13±0.34a | 0.74±0.25c | 1.15±0.33a |

| Mean systolic BP, mm Hg | 101±7 | 102±5 | 106±7 | 103±4 | 105±4 |

| Serum adiponectin, μg/ml | 10.6±1.2 | 10.8±1.4 | 4.6±0.5a | 4.7±0.9a | 4.5±0.7a |

Data are mean±SD. Cont, control; FBS, fasting blood sugar; HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1c; HOMAIR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; Cr, Creatinine; Ccr, creatinine clearance.

P<0.001 compared with other groups.

P<0.01 compared with other groups.

P<0.05 compared with other groups.

AdipoRon Activates the CaMKKβ/Phosphorylated Ser431LKB1/Phosphorylated Thr172AMPK/PPARα Pathway by Increasing Intrarenal AdipoR1/AdipoR2 Expression in db/db Mice

AdipoRon treatment restored diabetes-induced decrease in renal AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 expression to the levels present in control db/m mice, as indicated by abundant AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 distribution throughout the renal ultrastructure of diabetic mice (Figure 2, A–F). AdipoRon treatment increased CaMKKβ and phosphorylated LKB1 expression (Figure 2, D and G–I) and activated phosphorylated AMPK and PPARα, which are established to be the primary downstream targets of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2, respectively (Figure 2, J–L).

Figure 2.

AdipoRon activates the CaMKKβ/phosphorylated Ser431LKB1/phosphorylated Thr172AMPK/PPARα pathway by increasing intrarenal AdipoR1/AdipoR2 expression in db/db mice. (A–C) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining and quantitative analyses of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 expression. (D–I) Representative images of western blotting and quantitative analyses of AdipoR1, AdipoR2, CaMKKα, CaMKKβ, phosphorylated Ser431LKB1, total LKB1, and β-actin levels. (J–L) Representative images of western blotting and quantitative analyses of phosphorylated AMPK Thr172, total AMPK, PPARα, and β-actin levels. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus db/db mice. Cont, control.

AdipoRon Ameliorates Diabetes-Induced Renal Damage by Reducing Intrarenal Lipotoxicity and Oxidative Stress in db/db Mice

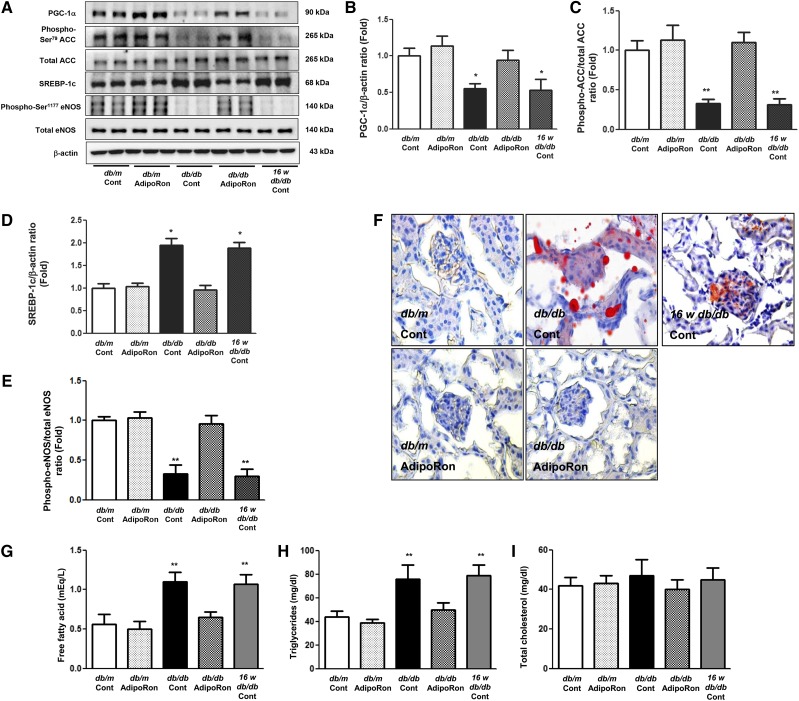

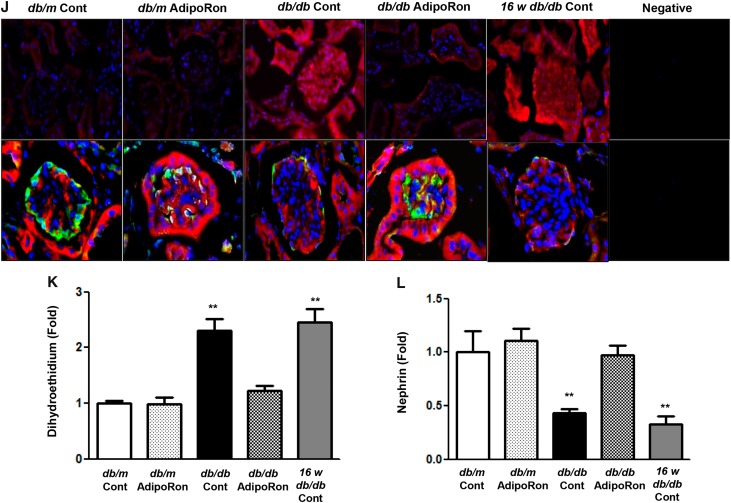

AdipoRon treatment restored PGC-1α, phosphorylated Ser75ACC, and phosphorylated Ser1177eNOS expression and decreased SREBP-1c expression in diabetic mice to the degree of those present in nondiabetic control mice (Figure 3, A–E). Even distribution of red lipid droplets throughout the glomerulus of diabetic mice disappeared after AdipoRon treatment (Figure 3F). Consistently, AdipoRon treatment decreased intrarenal triacylglycerol (TG) and FFA levels (Figure 3, G–I). Immunofluorescence analysis showed that AdipoRon treatment attenuated red chromophore (DHE) formation and transformed blackout into green (nephrin) in the glomerulus of db/db mice (Figure 3, J–L). Renal phenotypes of diabetic control and those before the treatment exhibited similar degree of diabetes-induced alterations; increased expansion of the mesangial area and numbers of glomerular collagen IV-, TGF-β–, and F4/80-positive cells. These renal alterations were restored by AdipoRon administration to the level present in nondiabetic control mice (Figure 4, A–E). Electron microscopy analysis revealed recovery of podocyte injury, including attenuation of glomerular basement membrane thickness, foot process effacement, and slit diaphragm width, in db/db mice (Figure 4, F–I). Moreover, AdipoRon treatment reduced the amount of TUNEL-positive endothelial (PECAM-1–positive) cells (Figure 4, J and K) and TUNEL-positive (WT-positive) podocytes (Figure 4, L–N) in diabetic mice. AdipoRon treatment decreased the levels of urinary oxidative stress markers 8-OH-dG and isoprostane in 24-hour urine collected from diabetic mice (Figure 4, O and P). Overall, AdipoRon-AdipoR1/AdipoR2 interaction–induced activation of the AMPK/PPARα pathway ameliorated lipotoxicity, apoptosis, and oxidative stress, which in turn alleviated the features of DN.

Figure 3.

AdipoRon ameliorates diabetes-induced intrarenal lipotoxicity and oxidative stress in db/db mice. (A–E) Representative images of western blotting and quantitative analyses of PGC-1α, phosphorylated ACC, total ACC, SREBP-1c, phosphorylated Ser1177eNOS, total eNOS, and β-actin levels. (F–I) Representative images of oil red O staining of the renal cortex and quantitative analyses of intrarenal NEFA, TG, and TC levels. (J–L) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining and quantitative analyses of DHE and nephrin expression. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus db/db mice. Cont, control.

Figure 4.

AdipoRon ameliorated features of DN through decreased intrarenal fibrosis, inflammation, apoptosis, and recovered podocyte injury. (A) Representative sections stained with PAS reagent are shown to estimate the mesangial fractional area (%) (B) together with the results of quantitative analysis according to groups. Immunohistochemical staining and quantitative analyses of (A and C) type IV collagen-, (A and D) TGF-β1-, and (A and E) F4/80-positive area. (F–I) Representative electron microscopic images of the glomerulus and quantitative analysis according to groups. (J and L, respectively) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining of TUNEL-positive endothelial cells and podocytes and (K, M, and N, respectively) quantitative analyses of the results. (O and P) Twenty-four-hour urinary 8-OH-dG and isoprostane levels in the study mice; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and #P<0.001 compared with other groups. Col IV, type IV collagen; Cont, control.

In Vitro Studies

AdipoRon-Induced Increase in Intracellular Ca++ Level Activates the CaMKKβ/Phosphorylated Ser431LKB1/Phosphorylated Thr172AMPK/PPARα Pathway and Ameliorates Lipotoxicity and Oxidative Stress in HGECs

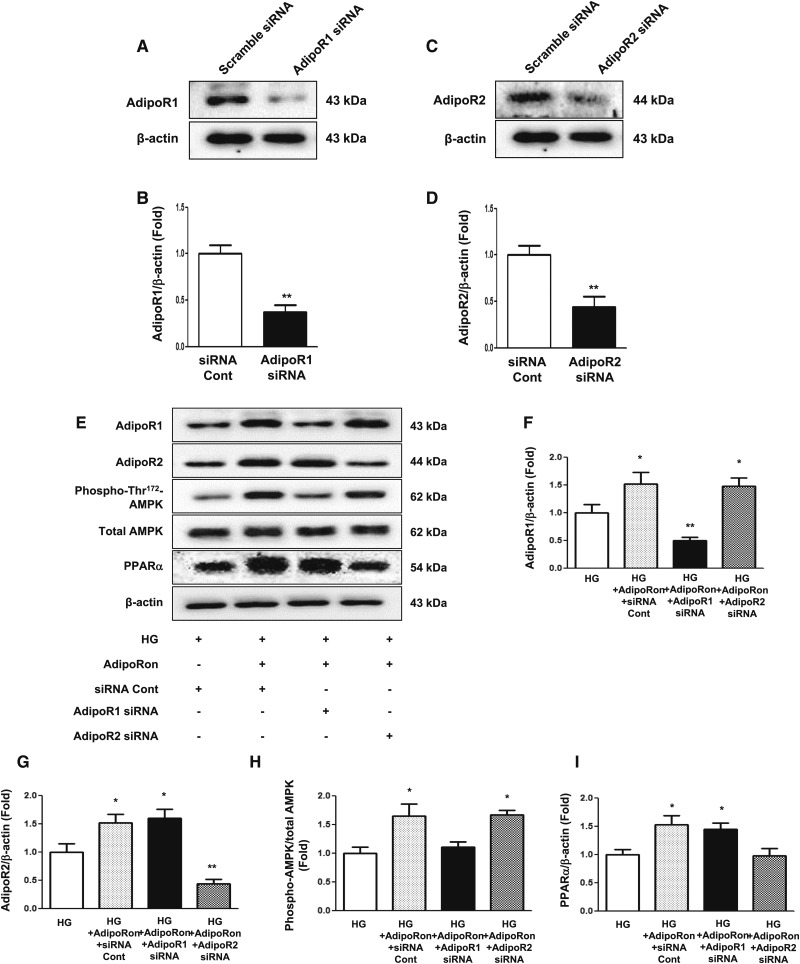

AdipoRon treatment increased intracellular Ca++ level in HGECs cultured in both low- and high-glucose media in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5, A–D). Immunofluorescence analysis showed that AdipoRon treatment increased phosphorylated LKB1 and phosphorylated AMPK levels in HGECs cultured in high-glucose medium (Figure 5, E–L). Moreover, AdipoRon-induced increase in CaMKKβ, phosphorylated LKB1, phosphorylated AMPK, and PPARα expression was associated with increased expression of their downstream effectors such as PGC-1α, phosphorylated ACC, and phosphorylated Ser1177eNOS and decreased expression of SREBP-1c in HGECs cultured in high-glucose medium (Figure 5, M–Q). Moreover, AdipoRon treatment attenuated DHE expression and decreased TUNEL-positive cell number (Figure 5, R–T). HGECs cultured in high-glucose medium were transfected with small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against genes encoding AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 to verify which one of the adiponectin receptors was responsible for activating its downstream effectors. Transfection of HGECs with AdipoR1 siRNA suppressed AdipoR1 expression and increased AdipoR2 expression to the level present in siRNA control–transfected cells treated with AdipoRon and vice versa (Figure 6, A–G). AdipoRon treatment increased phosphorylated AMPK, total AMPK, and PGC-1α expression in HGECs transfected with AdipoR2 siRNA but not in HGECs transfected with AdipoR1 siRNA; moreover, AdipoRon treatment increased PPARα expression in HGECs transfected with AdipoR1 siRNA but not in HGECs transfected with AdipoR2 siRNA (Figure 6, E and H–K). Moreover, AdipoRon treatment did not increase phosphorylated ACC, total ACC, phosphorylated endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), total eNOS, and NOx expression in HGECs transfected with AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 siRNA (Figure 6, J and L–N).

Figure 5.

AdipoRon-induced increase in intracellular Ca++ concentration activates its downstream signaling and ameliorates lipotoxicity and oxidative stress in HGECs. (A–D) Intracellular Ca++ concentration in HGECs cultured in low- or high-glucose medium with or without AdipoRon. (E–G) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining and quantitative analyses of phosphorylated Ser431LKB1 and phosphorylated Thr172AMPK levels. (H) Representative images of western blotting analysis of CaMKKβ, phosphorylated Ser431LKB1, phosphorylated Thr172AMPK, total AMPK, PPARα, and β-actin levels and (I–L) their quantitative analyses. (M–Q) Representative images of western blotting and quantitative analyses of PGC-1α, phosphorylated ACC, total ACC, SREBP-1c, phosphorylated Ser1177eNOS, total eNOS, and β-actin levels. (R–T) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining and quantitative analyses of DHE expression and TUNEL-positive cells. *P<0.05 compared with LG 0; **P<0.001 compared with LG and HG control, respectively; #P<0.001 compared with LG+10 and HG+10, respectively. Cont, control; HG, high-glucose; LG, low-glucose.

Figure 6.

Effect of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 siRNAs on downstream signaling of AdipoRon-treated HGECs indicates that AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 activate the AMPK and PPARα pathway, respectively. (A–I) Representative images of western blotting and quantitative analyses of AdipoR1, AdipoR2, phosphorylated Thr172AMPK, total AMPK, PPARα, and β-actin levels. (J–N) Representative images of western blotting and quantitative analyses of PGC-1α, phosphorylated ACC, total ACC, phosphorylated Ser1177eNOS, total eNOS, NOx, and β-actin levels; *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 compared with other groups. HG, high glucose; LG, low glucose.

AdipoRon-Induced Increase in Intracellular Ca++ Level Activates the CaMKKβ/Phosphorylated Ser431LKB1/Phosphorylated Thr172AMPK/PPARα Pathway and Ameliorates Lipotoxicity and Oxidative Stress in Murine Podocytes

AdipoRon treatment increased intracellular Ca++ level in murine podocytes cultured in both low- and high-glucose media in a dose-dependent manner (Supplemental Figure 2, A–D). Immunofluorescence analysis showed that AdipoRon treatment increased phosphorylated LKB1 and phosphorylated AMPK expression in murine podocytes cultured in high-glucose medium (Supplemental Figure 2, E–G). Moreover, AdipoRon-induced increase in CaMKKβ, phosphorylated LKB1, phosphorylated AMPK, and PPARα expression was associated with further increase in the expression of their downstream effectors such as PGC-1α, phosphorylated ACC, and phosphorylated Ser1177eNOS and decrease in the expression of SREBP-1c in murine podocytes cultured in high-glucose medium (Supplemental Figure 2, H–Q). Moreover, AdipoRon treatment attenuated DHE expression and decreased TUNEL-positive cell number in murine podocytes (Supplemental Figure 2, R–T).

AdipoRon-Induced Increase in Cardiac AdipoR1/AdipoR2 Expression Activates the CaMKKβ/Phosphorylated Ser431LKB1/Phosphorylated Thr172AMPK/PPARα Pathway and Ameliorates Cardiac Function and Phenotype

AdipoRon treatment improved systolic and diastolic functions as represented by increased fractional shortening, velocity of circumferential shortening, and E/A ratio without affecting cardiac mass in diabetic mice (Supplemental Figure 3, A and B). AdipoRon also decreased expression of trichrome-, collagen IV-, TGF-β1–, and CTGF-positive area and reduced TUNEL- and F4/80-positive cells, indicating improvement in cardiac fibrosis, apoptosis, and inflammation (Supplemental Figure 3, C–J). These favorable alterations were in line with increased expression of AdipoR1/AdipoR2 and CaMKKβ/phosphorylated Ser431LKB1/phosphorylated Thr172AMPK/PPARα pathway in the same study group (Supplemental Figure 3, K–R).

Discussion

Significant decrease in circulating adiponectin level with a concomitant decrease in AdipoR1/AdipoR2 expression in the muscle and adipose tissues of insulin-resistant ob/ob mice may be causally related to insulin resistance, dysfunctional lipid metabolism, and obesity.17 This is accompanied with decreased AMPK and PPARα activation, which further downregulates AdipoR expression. The resultant decrease in fatty acid oxidation and increase in fatty acid synthesis contribute to the progression of type 2 diabetes.18 Results of immunofluorescence staining of relevant receptors and molecules in the human diabetic kidneys performed in this study were consistent with those of previous studies, which showed a decrease in AdipoRs and CaMKKβ, LKB1, and AMPK expression, signifying the implication of AdipoR agonism in diabetes. Several studies have reported the favorable renal effect of adiponectin against albuminuria development in rodent models. Sharma et al.19 verified the renoprotective effects of adiponectin by using adiponectin-knockout mice. They showed that adiponectin treatment restored renal oxidative stress and that this was achieved through the activation of AMPK, which in turn was responsible for decreased podocyte permeability and albuminuria.19 Identification of AdipoR1/AdipoR2 prompted the need to develop the synthetic AdipoR agonist AdipoRon that mimicked the prometabolic effects of adiponectin but did not exert adverse effects associated with the chronic upregulation in serum adiponectin level.16

Whereas AdipoR1 is abundantly expressed in the skeletal muscle,20 AdipoR2 is mainly expressed in the liver.16 Both AdipoR1/AdipoR2 serve as the major AdipoRs for regulating glucose and lipid metabolism in different organs. In the view of renal structure, AdipoR1 is abundantly expressed in proximal tubular cells and endothelial cells, podocytes, mesangial cells, and Bowman’s capsule epithelial cells of the glomerulus; in contrast, AdipoR2 expression is relatively scarce across the renal structure.21,22 Models of chronic renal failure show increased renal AdipoR1/AdipoR2 expression with consistently upregulated serum and urinary adiponectin levels.23 This evidence suggests that upregulation of AdipoR expression is a compensatory mechanism to prevent ongoing renal damage. This study showed that AdipoRon treatment restored diabetes-induced downregulation of AdipoR1/AdipoR2 expression. However, this finding was challenging to the conventional concept that renal AdipoR2 expression is scarce, less announced than renal AdipoR1 expression.22 Results of this study showed that AdipoR2 expression was comparable to AdipoR1 expression and recovered after AdipoRon treatment. Because decreased AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 expression may decrease adiponectin sensitivity, upregulation of AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 expression after AdipoRon treatment may restore the renoprotective function of adiponectin. Regarding the mechanism through which AdipoR1/R2 become activated, it is reported that AdipoR1/AdipoR2 expression is inversely correlated with plasma insulin levels in vivo. Moreover, previous in vitro studies indicate that insulin decreases AdipoR1/AdipoR2 expression in hepatocytes through a phosphoinositide 3–kinase/FOXO1-dependent pathway.17 In line with this, improvement in the HOMA-IR index of diabetic mice suggests that increased insulin sensitivity is involved in AdipoR1/AdipoR2 activation.

The established concept on the role of AdipoRs and their associated pathway indicates that AdipoR1 activates the AMPK pathway, whereas AdipoR2 is associated with PPARα activation thus comprehensively reducing oxidative stress and increasing fatty acid oxidation.15 We investigated the AdipoR responsible for activating its downstream effectors by transfecting cultured HGECs with AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 siRNA. Consistent with the established role-play assigned to each AdipoR, inhibition of either one of the two receptors increased the expression of the other receptor to a greater extent as a compensatory mechanism. Moreover, suppression of either one of the two receptors affected the expression of one’s assumable downstream effectors, confirming that phosphorylated AMPK/PGC1α pathway and PPARα were the primary downstream targets of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2, respectively. However, expression of further downstream effectors, including phosphorylated ACC, total ACC, phosphorylated eNOS, total eNOS, and NOx, did not increase in HGECs transfected with AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 siRNA even after AdipoRon treatment, suggesting that dual activation of AdipoR1/AdipoR2 is required for exerting prometabolic effects through the AMPK/PPARα axis.

AdipoR activation stimulates AMPK and PPARα to produce antidiabetic effects through their downstream effectors PGC-1α, ACC, and SREBP-1c. AMPK and PPARα modulate lipid metabolism by regulating fatty acid oxidation. ACC, a key enzyme that catalyzes the rate-limiting steps of fatty acid synthesis, is inactivated upon phosphorylation by AMPK, further accelerating fatty acid oxidation. On the other hand, AMPK and PPARα activation suppresses the expression of such lipogenesis-associated enzymes as SREBP-1c. Moreover, PPARα-activated PGC-1α/β/estrogen-related receptor (ERR)–1α axis reduces oxidative stress by enhancing mitochondrial oxidative capacity.24,25 Increased eNOS level is expected to neutralize ROS, reduce adhesion molecule synthesis, and suppress cell proliferation, which collectively help confer protective effects on endothelial cells against albuminuria development.26–28

In keeping with an expanding body of evidence that endothelial dysfunction is a major contributor in the pathogenesis of DN and because glomerular podocyte injury is a major cause of albuminuria and glomerulosclerosis in patients with diabetes,29 we explored changes in relevant signaling pathways in both HGECs and podocytes. The decreased number of functioning podocytes is an independent risk factor for the development and progression of DN.29 In this study, results of in vitro experiments were consistent with those of in vivo experiments, suggesting that AdipoRon exerted favorable effects on cellular levels as well by activating AMPK. The net effect was reduced oxidative stress and apoptosis in different cell types, which improved the renal phenotype in terms of restored podocyte number and decreased podocyte foot process widening. These alterations ultimately decreased urinary albumin excretion rate. Moreover, decreased creatinine clearance observed in AdipoRon-treated db/db mice proposes its possible renoprotective mechanism in which improved hyperinsulinemia-induced hyperfiltration would further enhance reciprocal regulation between HGECs and podocytes, resulting in reduced albuminuria. Collectively, the results of in vitro experiments suggest that endothelial dysfunction affects podocyte injury and resultant albuminuria by altering paracrine communication or crosstalk between HGECs and podocytes.

Next, we explored the expression of LKB1 and CaMKK, which are upstream AMPK kinases,30 to determine the missing link between AdipoRs and key AdipoR-activated molecules. Enhanced cytosolic LKB1 localization and Ca++-induced CaMKK activation promote adiponectin-stimulated AMPK activation in muscle cells.31 Among two isoforms of CaMKK, AdipoRon seems to activate CaMKKβ rather than CaMKKα in the kidneys by stimulating intracellular Ca++ release. AdipoRon treatment of HGECs and murine podocytes increased intracellular Ca++ concentration in a dose-dependent manner. Although LKB1 activates AMPK primarily through an AMP-dependent mechanism under high cellular energy stress,32 CaMKKs phosphorylate AMPK through Ca++/calmodulin independent of AMP.33 Viewed in this light, both the upstream signaling pathways involved in AdipoRon-induced AMPK activation provide a mechanism in which regulation of AMPK activity could be dynamically yet finely tuned in accordance with the surrounding environmental and nutritional requirements.34 Moreover, CaMKKβ activation by AdipoRon-induced Ca++ influx serves as exercise mimetics further enhancing PGC-1α expression independently of AMPK.

Several studies have reported that AdipoRon exerts a glucose-lowering effect. However, this study did not show changes in serum glucose and HbA1c levels in AdipoRon-treated db/db mice.15 This discrepancy may be because of the use of different doses (50 mg/kg versus 30 mg/kg) and treatment durations (10 days versus 4 weeks). Nevertheless, these favorable results reinforce to attest to the role of AdipoRon in attenuating renal lipotoxicity independent of its systemic glucose-lowering effect.

In terms of hemodynamic effect, AdipoRon improved both systolic and diastolic heart functions without affecting cardiac mass that was accompanied by decreased cardiac fibrosis, inflammation, and apoptosis. These favorable effects on diabetic heart were delivered through the activation of both AdipoRs and their downstream pathway that was delineated in the kidney. This is in accordance with previous studies that associate reduced expression of AdipoR1 in the heart muscle to intolerance of ischemic injury35 and consequent pathologic processes36 and that reduced activities of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes; i.e., of AMPK, and PGC1 signaling contribute to diabetic cardiomyopathy.37

Results of this study clearly demonstrated that AdipoRon improved high-glucose–induced oxidative stress and lipotoxicity by activating intrarenal AdipoR1/AdipoR2, which in turn activated the intracellular Ca++/AMPK/PPARα pathway without affecting serum adiponectin level. Human diabetic kidneys exhibit decreased AdipoR1/AdipoR2, CaMKKβ, phosphorylated AMPK, phosphorylated LKB1, and nephrin expression even in the early stages of CKD and show negligible changes in relevant molecular expression with increasing stages of CKD. Moreover, significant improvements in renal function and phenotype before and after the treatment of AdipoRon to the degree comparable to that of db/m control mice represent its reversal effect in the progression of DN. These findings suggest that when translated into the clinical field, AdipoR agonism in the kidneys is a promising therapeutic strategy for activating AMPK. In this context, AdipoRon may be a novel promising candidate to start with in greeting the new era of DN.

Concise Methods

Study Subjects

The study recruited a total of 33 healthy subjects (n=6) and type 2 diabetic patients (n=27) with various stages of CKD according to the modified GFR (Supplemental Table 1). We reviewed biopsy samples of human diabetic kidneys and nondiabetic kidneys according to CKD stages. Experimental research involving human specimens was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the College of Medicine, Catholic University of Korea (KC16SISI0158).

Experimental Methods

Six-week-old male C57BLKS/J db/m and db/db mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Male C57BLKS/J db/m and db/db mice were divided into four groups, and received either a regular diet chow or a diet containing AdipoRon. AdipoRon (30 mg/kg; Sigma, St Louis, MO) was mixed into the standard chow diet and provided to db/db mice (db/db+AdipoR, n=8) and age- and sex-matched db/m mice (db/m+AdipoR, n=8) from 16 weeks of age for 4 weeks. Control db/db (db/db cont, n=8) and db/m mice (db/m cont, n=8) were fed normal diet chow. At weeks 16 and 20, all animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 30 mg/kg tiletamine plus zolazepam (Zoletil; Virbac, Carros, France) and 10 mg/kg xylazine hydrochloride (Rompun; Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany) to compare the effect of AdipoRon before and after the treatment. Blood was collected from the left ventricle and the plasma was stored at −70°C for subsequent analyses. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Laboratory Animals Welfare Act, Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the College of Medicine, Catholic University of Korea (CUMC-2017–0251–01).

Assessment of Renal Function and Oxidative Stress and Intrarenal Lipids

A 24-hour urine collection was obtained using metabolic cages at weeks 16 and 20 and urinary albumin concentration was measured by an immunoassay (Bayer, Elkhart, IN). Plasma and urine creatinine concentrations were measured by an enzymatic creatinine assay (Samkwang Medical Laboratory, Seoul, Korea). The concentration of serum adiponectin was determined by ELISA (Biosource, Camarillo, CA). To evaluate oxidative stress, we measured the 24-hour urinary 8-OH-dG (8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine; OXIS Health Products, Inc., Portland, OR), 8-epi-PG F2α (OXIS Health Products, Inc., Portland, OR), and NOx (BioVision, Mountain View, CA). The kidney lipids were extracted by the method of Bligh and Dyer with slight modifications as previously described.38 Total cholesterol and TG concentrations were measured by an autoanalyzer (Hitachi 917, Tokyo, Japan) using commercial kits (Wako, Osaka, Japan). Nonesterified fatty acid levels were measured with a JCA-BM1250 automatic analyzer (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). In addition, we performed oil red O staining to evaluate the effect of AdipoRon on lipid accumulation in the glomerulus.

Light Microscopic Study

Kidney samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. The histology was assessed after periodic acid–Schiff staining (PAS) and trichrome staining. The mesangial matrix and glomerular tuft areas were quantified for each glomerular cross-section using PAS-stained sections as previously reported.39 More than 30 glomeruli which were cut through the vascular pole were counted per kidney and the average was used for analysis. Heart samples collected after systemic perfusion with PBS were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Ten consecutive heart cross-sections stained in trichrome were analyzed.

Immunohistochemistry

We performed immunohistochemistry for TGF-β1, type IV collagen, F4/80, TUNEL, and CTGF. Renal (4-µm thick) and cardiac (5-µm thick) tissue sections were incubated overnight with anti–TGF-β1 (1:100; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), anti-COL IV (1:200; Biodesign International, Saco, ME), and anti-F4/80 (1:200; Serotek, Oxford, UK) antibodies with additional cardiac tissue staining for anti-CTGF (1:250 in blocking solution; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and the in situ TUNEL assay (Apoptag Plus; Intergen, New York, NY) in a humidified chamber at 4°C. The antibodies were localized using a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and the Vector Impress kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) with a 3,3-diamninobenzidine substrate solution with nickel chloride enhancement. The sections were then dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in xylene, and mounted without counterstaining. The sections were examined in a blinded manner under light microscopy (Olympus BX-50; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan). To quantify the stained areas, approximately 20 views (200× and 400× magnifications) were used, which were located randomly in the renal cortex and corticomedullary junction of each slide (Scion Image Beta 4.0.2, Frederick, MD). For cardiac tissues, 20 views were randomly located in the middle portion of the myocardium of each slide (Scion Image Beta 4.0.2).

Immunofluorescence Analysis

We performed immunofluorescence analysis for AdipoR1, AdipoR2, CaMKKβ, pLKB1, pAMPKα, PECAM-1, WT1, DHE, TUNEL, and nephrin by using tyramide signal amplification fluorescence system (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) and counterstained with the 4,6-diamidino2-phenylindole (DAPI). Detection of apoptotic cells in the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue was performed by in situ TUNEL, using an ApopTag In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Chemicon-Millipore, Billerica, MA). The TUNEL reaction was assessed in the whole glomeruli biopsy sample under 200× and 400× magnifications. The fluorescent images were examined under a laser scanning confocal microscope system (Carl Zeiss LSM 700, Oberkochen, Germany).

Electron Microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy, kidney specimens were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer overnight at 4°C. After washing in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, the specimens were postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer for 1 hour. The specimens were then dehydrated using a series of graded ethanol, exchanged through acetone, and embedded in Epon 812. Ultrathin sections (approximately 70–80 nm) were obtained by ultramicrotome (Leica Ultracut UCT, Leica, Germany) and were double stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined using a transmission electron microscope (JEM 1010, Tokyo, Japan) at 60 kV. We measured GBM thickness, slit diaphragm diameter, and foot process width within at least four glomeruli from each mouse, and four mice from each study group were examined.

Western Blot Analysis and Enzyme Activity Determination

The total proteins of the renal cortical and cardiac tissues were extracted with a Pro-Prep Protein Extraction Solution (Intron Biotechnology, Gyeonggi-Do, Korea), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Western assay was performed with specific antibodies for AdipoR1 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), AdipoR2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), phospho-Thr172 AMPK (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), total AMPK (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), PPARα (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), PPARγ coactivator (PGC)–1α (1:2000; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), sterol regulatory element–binding protein (SREBP)–1c (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), phosphorylated acetyl-CoA carboxylase (pACC) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), total ACC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), phospho-Ser1177 eNOS (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), total eNOS (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After incubation with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), target proteins were visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (ECL Plus; GE Healthcare Bio-Science, Piscataway, NJ).

Cell Culture and siRNA Transfection

HGECs (Angio-Proteomie, Boston, MA) were cultured in endothelial growth medium (Angio-Proteomie, Boston, MA) at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere. Passages 4–8 were used in all experiments. We also cultured conditionally immortalized mouse podocytes that were kindly provided by Dr. Kang (Yonsei University, College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea) as previously described.40 The HGECs and podocytes were then exposed to low glucose (5 mmol/L D-glucose) or high glucose (35 mmol/L D-glucose), with or without the additional 6-hour application of AdipoRon (5, 10, and 50 nM). Western blot analysis was performed with specific antibodies for AdipoR1, AdipoR2, phospho-Thr172 AMPK, total AMPK, and β-actin. siRNAs, targeted to AdipoR1, AdipoR2, and scrambled siRNA (siRNA cont), were complexed with transfection reagent (Lipofectamine 2000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The sequences of the siRNAs were as follows: AdipoR1, 5′-GGACAACGACUAUCUGCUACATT-3′; AdipoR2, 5′-CCAACUGGAUGGUACACGA-3′; and nonspecific scrambled siRNA, 5′-CCUACGCCACCAAUUUCGU-3′ (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea). HGECs in six-well plates were transfected with a final concentration of 50 nM AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 siRNAs using Lipofectamine2000 in Opti-MEM(R) I reduced serum medium (Gibco Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 24 hours and then the medium was changed back to growth medium for additional incubation. After transfection, cells were treated with AdipoRon (50 nM) in high-glucose media to evaluate the effects of siRNAs on HGECs reactions.

Intracellular Ca2+ Measurement

Calcium concentrations were determined from the ratio of fura-2 fluorescence intensity at 340-nm excitation and 380-nm excitation. The 340-nm fluorescence of fura-2 increases and the 380-nm fluorescence decreases with increasing intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i). For [Ca2+]i measurements, HGECs and podocytes (20,000 cells/well) were plated on black 96-well plates with a clear bottom in complete medium. After 1 day the cells were serum-starved for 2 hours. In the last 45 minutes of calcium-free serum-starvation, 5 µM FURA-2AM was added to the cells, then rinsed with Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY). FURA-2AM–loaded cells were sequentially excited at 340 and 380 nm by spectrophotometer microplate reader (Synergy MX; BioTek, Winooski, VT). AdipoRon-induced [Ca2+]i were quantified by measurement of area under curve and peak amplitude for the rise in relative [Ca2+]i.

Assessment of Cardiac Function by Echocardiographic Parameters

Cardiac size and function were assessed by an echocardiogram using a Hewlett-Packard Sonus 4500 ultrasound machine (Agilent Technologies, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada) while the animals were anesthetized.

Statistical Analyses

The data are expressed as means±SD. Differences between the groups were examined for statistical significance using ANOVA with Bonferroni correction using SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (J.H.L.: 2015R1D1A1A01056984, and C.W.P.: 2016R1A2B2015980).

The abstract of this study appeared on a poster for the American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week 2017, held in New Orleans, LA, on November 2, 2017.

Y.K., J.H.L., M.Y.K., E.N.K., H.E.Y., S.J.S., B.S.C., Y.S.K., Y.S.C., and C.W.P. designed and conceptualized the experiments. Y.K., J.H.L., M.Y.K., and C.W.P. conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. Y.K. and C.W.P. wrote the manuscript. All of the authors critically analyzed the manuscript and approved its final version for publication.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2017060627/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Jiang T, Wang Z, Proctor G, Moskowitz S, Liebman SE, Rogers T, Lucia MS, Li J, Levi M: Diet-induced obesity in C57BL/6J mice causes increased renal lipid accumulation and glomerulosclerosis via a sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 280: 32317–32325, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg IJ, Trent CM, Schulze PC: Lipid metabolism and toxicity in the heart. Cell Metab 15: 805–812, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu L, Shi X, Bharadwaj KG, Ikeda S, Yamashita H, Yagyu H, Schaffer JE, Yu YH, Goldberg IJ: DGAT1 expression increases heart triglyceride content but ameliorates lipotoxicity. J Biol Chem 284: 36312–36323, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yilmaz M, Hotamisligil GS: Damned if you do, damned if you don’t: The conundrum of adipose tissue vascularization. Cell Metab 17: 7–9, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hotta K, Funahashi T, Arita Y, Takahashi M, Matsuda M, Okamoto Y, Iwahashi H, Kuriyama H, Ouchi N, Maeda K, Nishida M, Kihara S, Sakai N, Nakajima T, Hasegawa K, Muraguchi M, Ohmoto Y, Nakamura T, Yamashita S, Hanafusa T, Matsuzawa Y: Plasma concentrations of a novel, adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in type 2 diabetic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 1595–1599, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Jong PE, Curhan GC: Screening, monitoring, and treatment of albuminuria: Public health perspectives. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2120–2126, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG: AMP-activated protein kinase: Ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab 1: 15–25, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, Terauchi Y, Kubota N, Hara K, Mori Y, Ide T, Murakami K, Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Ezaki O, Akanuma Y, Gavrilova O, Vinson C, Reitman ML, Kagechika H, Shudo K, Yoda M, Nakano Y, Tobe K, Nagai R, Kimura S, Tomita M, Froguel P, Kadowaki T: The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med 7: 941–946, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamba S, Nakatsuji H, Kishida K, Noguchi M, Ogawa T, Okauchi Y, Nishizawa H, Imagawa A, Nakamura T, Matsuzawa Y, Funahashi T, Shimomura I: Relationship between visceral fat accumulation and urinary albumin-creatinine ratio in middle-aged Japanese men. Atherosclerosis 211: 601–605, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kacso IM, Bondor CI, Kacso G: Plasma adiponectin is related to the progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes patients. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 72: 333–339, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christou GA, Kiortsis DN: The role of adiponectin in renal physiology and development of albuminuria. J Endocrinol 221: R49–R61, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cha DR, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Wu J, Su D, Han JY, Fang X, Yu B, Breyer MD, Guan Y: Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha/gamma dual agonist tesaglitazar attenuates diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice. Diabetes 56: 2036–2045, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holland WL, Scherer PE: Cell Biology. Ronning after the adiponectin receptors. Science 342: 1460–1461, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang J, Zhang D, Li J, Zhang X, Fan F, Guan Y: Role of PPARgamma in renoprotection in Type 2 diabetes: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Clin Sci (Lond) 116: 17–26, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okada-Iwabu M, Yamauchi T, Iwabu M, Honma T, Hamagami K, Matsuda K, Yamaguchi M, Tanabe H, Kimura-Someya T, Shirouzu M, Ogata H, Tokuyama K, Ueki K, Nagano T, Tanaka A, Yokoyama S, Kadowaki T: A small-molecule AdipoR agonist for type 2 diabetes and short life in obesity. Nature 503: 493–499, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamauchi T, Nio Y, Maki T, Kobayashi M, Takazawa T, Iwabu M, Okada-Iwabu M, Kawamoto S, Kubota N, Kubota T, Ito Y, Kamon J, Tsuchida A, Kumagai K, Kozono H, Hada Y, Ogata H, Tokuyama K, Tsunoda M, Ide T, Murakami K, Awazawa M, Takamoto I, Froguel P, Hara K, Tobe K, Nagai R, Ueki K, Kadowaki T: Targeted disruption of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 causes abrogation of adiponectin binding and metabolic actions. Nat Med 13: 332–339, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuchida A, Yamauchi T, Ito Y, Hada Y, Maki T, Takekawa S, Kamon J, Kobayashi M, Suzuki R, Hara K, Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Froguel P, Nakae J, Kasuga M, Accili D, Tobe K, Ueki K, Nagai R, Kadowaki T: Insulin/Foxo1 pathway regulates expression levels of adiponectin receptors and adiponectin sensitivity. J Biol Chem 279: 30817–30822, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Handa P, Maliken BD, Nelson JE, Morgan-Stevenson V, Messner DJ, Dhillon BK, Klintworth HM, Beauchamp M, Yeh MM, Elfers CT, Roth CL, Kowdley KV: Reduced adiponectin signaling due to weight gain results in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through impaired mitochondrial biogenesis. Hepatology 60: 133–145, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma K, Ramachandrarao S, Qiu G, Usui HK, Zhu Y, Dunn SR, Ouedraogo R, Hough K, McCue P, Chan L, Falkner B, Goldstein BJ: Adiponectin regulates albuminuria and podocyte function in mice. J Clin Invest 118: 1645–1656, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwabu M, Yamauchi T, Okada-Iwabu M, Sato K, Nakagawa T, Funata M, Yamaguchi M, Namiki S, Nakayama R, Tabata M, Ogata H, Kubota N, Takamoto I, Hayashi YK, Yamauchi N, Waki H, Fukayama M, Nishino I, Tokuyama K, Ueki K, Oike Y, Ishii S, Hirose K, Shimizu T, Touhara K, Kadowaki T: Adiponectin and AdipoR1 regulate PGC-1alpha and mitochondria by Ca(2+) and AMPK/SIRT1. Nature 464: 1313–1319, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cammisotto PG, Londono I, Gingras D, Bendayan M: Control of glycogen synthase through ADIPOR1-AMPK pathway in renal distal tubules of normal and diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F881–F889, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perri A, Vizza D, Lofaro D, Gigliotti P, Leone F, Brunelli E, Malivindi R, De Amicis F, Romeo F, De Stefano R, Papalia T, Bonofiglio R: Adiponectin is expressed and secreted by renal tubular epithelial cells. J Nephrol 26: 1049–1054, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu Y, Bao BJ, Fan YP, Shi L, Li SQ: Changes of adiponectin and its receptors in rats following chronic renal failure. Ren Fail 36: 92–97, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong YA, Lim JH, Kim MY, Kim TW, Kim Y, Yang KS, Park HS, Choi SR, Chung S, Kim HW, Kim HW, Choi BS, Chang YS, Park CW: Fenofibrate improves renal lipotoxicity through activation of AMPK-PGC-1α in db/db mice. PLoS One 9: e96147, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim MY, Lim JH, Youn HH, Hong YA, Yang KS, Park HS, Chung S, Ko SH, Shin SJ, Choi BS, Kim HW, Kim YS, Lee JH, Chang YS, Park CW: Resveratrol prevents renal lipotoxicity and inhibits mesangial cell glucotoxicity in a manner dependent on the AMPK-SIRT1-PGC1α axis in db/db mice. Diabetologia 56: 204–217, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis BJ, Xie Z, Viollet B, Zou MH: Activation of the AMP-activated kinase by antidiabetes drug metformin stimulates nitric oxide synthesis in vivo by promoting the association of heat shock protein 90 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Diabetes 55: 496–505, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouedraogo R, Wu X, Xu SQ, Fuchsel L, Motoshima H, Mahadev K, Hough K, Scalia R, Goldstein BJ: Adiponectin suppression of high-glucose-induced reactive oxygen species in vascular endothelial cells: Evidence for involvement of a cAMP signaling pathway. Diabetes 55: 1840–1846, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rakatzi I, Mueller H, Ritzeler O, Tennagels N, Eckel J: Adiponectin counteracts cytokine- and fatty acid-induced apoptosis in the pancreatic beta-cell line INS-1. Diabetologia 47: 249–258, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siddiqi FS, Advani A: Endothelial-podocyte crosstalk: The missing link between endothelial dysfunction and albuminuria in diabetes. Diabetes 62: 3647–3655, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Minokoshi Y, Ito Y, Waki H, Uchida S, Yamashita S, Noda M, Kita S, Ueki K, Eto K, Akanuma Y, Froguel P, Foufelle F, Ferre P, Carling D, Kimura S, Nagai R, Kahn BB, Kadowaki T: Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat Med 8: 1288–1295, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou L, Deepa SS, Etzler JC, Ryu J, Mao X, Fang Q, Liu DD, Torres JM, Jia W, Lechleiter JD, Liu F, Dong LQ: Adiponectin activates AMP-activated protein kinase in muscle cells via APPL1/LKB1-dependent and phospholipase C/Ca2+/Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem 284: 22426–22435, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanders MJ, Grondin PO, Hegarty BD, Snowden MA, Carling D: Investigating the mechanism for AMP activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Biochem J 403: 139–148, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suter M, Riek U, Tuerk R, Schlattner U, Wallimann T, Neumann D: Dissecting the role of 5′-AMP for allosteric stimulation, activation, and deactivation of AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 281: 32207–32216, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woods A, Dickerson K, Heath R, Hong SP, Momcilovic M, Johnstone SR, Carlson M, Carling D: Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta acts upstream of AMP-activated protein kinase in mammalian cells. Cell Metab 2: 21–33, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Su S, Zong X: Analysis of the association between adiponectin, adiponectin receptor 1 and diabetic cardiomyopathy. Exp Ther Med 7: 1023–1027, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Ma XL, Lau WB: Cardiovascular adiponectin resistance: The critical role of adiponectin receptor modification. Trends Endocrinol Metab 28: 519–530, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koentges C, König A, Pfeil K, Hölscher ME, Schnick T, Wende AR, Schrepper A, Cimolai MC, Kersting S, Hoffmann MM, Asal J, Osterholt M, Odening KE, Doenst T, Hein L, Abel ED, Bode C, Bugger H: Myocardial mitochondrial dysfunction in mice lacking adiponectin receptor 1. Basic Res Cardiol 110: 37, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delaney B, Nicolosi RJ, Wilson TA, Carlson T, Frazer S, Zheng GH, Hess R, Ostergren K, Haworth J, Knutson N: Beta-glucan fractions from barley and oats are similarly antiatherogenic in hypercholesterolemic Syrian golden hamsters. J Nutr 133: 468–475, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin SJ, Lim JH, Chung S, Youn DY, Chung HW, Kim HW, et al.: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha activator fenofibrate prevents high-fat diet-induced renal lipotoxicity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertens Res. 32: 835–845, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mundel P, Reiser J, Zúñiga Mejía Borja A, Pavenstädt H, Davidson GR, Kriz W, Zeller R: Rearrangements of the cytoskeleton and cell contacts induce process formation during differentiation of conditionally immortalized mouse podocyte cell lines. Exp Cell Res 236: 248–258, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.