Abstract

Objective

Mixed neuropathologies are the most common cause of dementia at the population level, but how different neuropathologies contribute to cognitive decline at the individual level remains unknown. We quantified the contribution of nine neuropathologies to cognitive loss at an individual level.

Methods

Participants (n=1,079) came from 2 longitudinal clinical-pathologic studies of aging. All completed 2+ cognitive evaluations (maximum = 22), died and underwent neuropathologic examinations to identify Alzheimer's disease (AD), other neurodegenerative diseases, and vascular pathologies. Linear mixed models examined associations of neuropathologies with cognitive decline and estimated the proportion of cognitive loss accounted for by each neuropathology at a person-specific level.

Results

Neuropathology was ubiquitous, with 94% of participants having 1+, 78% having 2+, 58% having 3+, and 35% having 4+. AD was most frequent (65%) but rarely occurred in isolation (9%). Remarkably, more than 230 different neuropathologic combinations were observed, each of which occurred in <6% of the cohort. The relative contributions of specific neuropathologies to cognitive loss varied widely across individuals. Although AD accounted for an average of about 50% of the observed cognitive loss, the proportion accounted for at the individual level ranged widely from 22% to 100%. Lewy bodies and hippocampal sclerosis also had potent effects, but again their impacts varied at the person-specific level.

Interpretation

There is much greater heterogeneity in the comorbidity and cognitive impact of age-related neuropathologies than currently appreciated, suggesting an urgent need for novel therapeutic approaches that embrace the complexity of disease to combat cognitive decline in old age.

Progressive loss of cognitive function is common in old age, and prevention of age-related cognitive decline is a critical public health priority. Efforts to mitigate late life cognitive decline have met with limited success, however, in part due to the complexity of factors that contribute to cognitive aging. Whereas it is widely recognized that Alzheimer’s disease (AD), cerebrovascular disease (CVD) and Lewy body disease (LBD) are important drivers of late life cognitive decline and dementia, recent work has shown that several additional age-related neuropathologies (i.e., TDP43, hippocampal sclerosis, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, atherosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis) also are common and relatively independently associated with decline.1–8 In fact, mixed neuropathologies are the most common cause of the clinical syndrome of dementia, including AD dementia.9–13 Mixed neuropathologies also are common among persons with mild or no cognitive impairment and are related to decline.14,15 Importantly, however, individuals have different combinations of neuropathologies, yet prior studies have not examined the degree to which specific combinations of neuropathologies contribute to cognitive loss at an individual level. Thus, our understanding of the relative effect of any given neuropathology and the potential impact of a therapeutic agent that targets a specific neuropathology in an individual is extremely limited.

We previously reported that common age-related neuropathologies account for less than half of the between-person variability in late life cognitive decline.4 In this study, we examined patterns of neuropathologic comorbidity and quantified the contribution of nine age-related neuropathologies to pathologic cognitive loss at a person-specific level. Participants were more than 1,000 deceased individuals from 2 longitudinal epidemiologic, clinical-pathologic studies of aging, completed at least 2 cognitive evaluations (maximum = 22), died and underwent uniform neuropathologic examinations. In analyses, we used linear mixed models to first examine the associations of the neuropathologies with cognitive decline. We then quantified each person’s cognitive loss attributable to neuropathology over the entire study period and determined the proportion of cognitive loss accounted for by each relevant neuropathology at a person-specific level.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were deceased persons from two longitudinal, epidemiologic, clinical-pathologic studies of aging, the Religious Orders Study and the Memory and Aging Project.16,17 These studies were approved by the Rush Institutional Review Board and informed consent and an Anatomical Gift Act were obtained from each participant. At the time of these analyses (mid-February 2017), 3,272 older persons were enrolled in these studies. Of the 1,636 individuals who had died, 1,416 underwent brain autopsy with an overall autopsy rate of 86.6%. We excluded individuals who only had 1 cognitive assessment before death (N=103) or did not have data on any one or more of the nine neuropathologies assessed (N=234). The analyses were performed on the remaining 1,079 older persons.

Assessment of global cognitive function

Performance on 17 cognitive tests was used to compute a composite measure of global cognition. For computation of the composite measure, scores on individual tests were converted to z scores using the baseline mean and standard deviation of all participants in both studies, and the z scores were averaged together.4 Further information on this measure and the individual tests is published in detail elsewhere.4,8

Neuropathologic evaluation

Brain autopsy procedures have been described in detail and were done by examiners unaware of all clinical information.3,4,8 Briefly, brains were removed, weighed, and hemispheres were cut coronally using a Plexiglas jig into 1-cm slabs. One hemisphere was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. After gross examination of both hemispheres, 9 brain regions of interest (i.e., midfrontal, midtemporal, inferior parietal, anterior cingulate, entorhinal and hippocampal cortices, basal ganglia, thalamus and midbrain) were dissected from the 1-cm slabs of fixed tissue and processed and embedded in paraffin. Sections (6 µm) from the paraffin blocks were stained for assessment of pathology.

Neurodegenerative pathologies

AD pathology (i.e., neuritic plaques, diffuse plaques and neurofibrillary tangles) was visualized using a modified Bielschowsky silver stain and a diagnosis of pathologic AD was determined according to modified recommendations of the National Institute on Aging (NIA)–Reagan criteria (i.e., intermediate or high likelihood).9 The presence of neocortical Lewy body pathology was determined using antibodies to α-synuclein.13 The presence of hippocampal sclerosis was determined using H&E stain.19 The presence of TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusions was determined using antibodies to phosphorylated TDP-43 (pS409/410; 1:100); TDP-43 distribution was grouped into 3 stages (stage 1, localized to amygdala; stage 2, extension to hippocampus or entorhinal cortex; stage 3, extension to the neocortex) and TDP-43 was considered present if positive for stages 2 or 3.8,11

Vascular pathologies

Gross (chronic) infarcts were identified by visually examining slabs and pictures from both brain hemispheres and confirmed histologically, and microinfarcts (chronic) were identified under microscopy using hematoxylin and eosin stain.4,12 Moderate-severe arteriolar sclerosis was detected by use of hematoxylin and eosin stained sections of the anterior basal ganglia.3 Moderate-severe atherosclerosis was detected by visual inspection of vessels in the Circle of Willis.3,5 Moderate-severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy was detected using amyloid-β immunostaining in 4 cortical regions.3,5

Statistical Analysis

The frequencies of each of the age-related neuropathologies are reported. Using annual cognitive scores as the continuous longitudinal outcome, we used linear mixed models to examine the associations of the neuropathologic indices with cognitive decline over many years prior to death. The primary model was specified as follows. Denote the observed cognitive score for participant i at time j by yij and denote the presence of neuropathologic index k for participant i by Xik, where i = 1 ⋯ N, j = 1 ⋯ mi and k = 1 ⋯ K. The score yij was estimated by . The term tij refers to time in years prior to death. The adjusted mean rate of cognitive decline was estimated by β0 and the association of kth neuropathology with cognitive decline was estimated by βk.

Notably, the model specification allowed us to examine the relative impact of specific neuropathologies on cognition while taking into account each person’s combination of neuropathologies (i.e., at a person-specific level). Specifically, for participant i, the total loss of cognition over the entire study period associated with the participant’s specific combination of the K neuropathologies was estimated by ; then, the proportion of cognitive loss due to a particular pathology k was calculated as . The distribution of person-specific proportions of cognitive loss accounted for by each neuropathology was graphically examined and summary statistics were used to quantify the relative impact of each neuropathology on cognition. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS/STAT software, version 9.4 for Linux (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). The models were controlled for age, sex and education. Statistical significance was determined at α level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of study participants

Participants were followed annually for up to 22 years (mean=8.3, Standard deviation (SD)=4.8) and died at a mean age of 89.7 years (SD=6.5). All had undergone brain autopsies with a mean postmortem interval of 9.1 hours (SD=7.8). Considerable decline in cognition was observed over the course of follow up; this was evident from the difference between the starting level of cognition (mean=−0.10, SD=0.62) and the level proximate to death (mean=−0.84, SD=1.11). By the time of death, 459 participants (43.2%) were diagnosed with the clinical syndrome of AD dementia, 18 (1.7%) with another primary cause of dementia, 261 (24.6%) with mild cognitive impairment, and 324 (30.5%) had no cognitive impairment.

Frequency and comorbidity of age-related neuropathologies

At autopsy, over 94% of participants (N=1,017) exhibited at least one neuropathology. Consistent with our previous findings, AD was most commonly observed, with 65.3% of participants meeting criteria for pathologic AD according to NIA Reagan criteria. TDP-43 pathology was observed in over a third of participants (34.9%). Chronic macroscopic infarcts and chronic microinfarcts were present in 36.0% and 30.0%, respectively. Cerebral vessel diseases were also quite common; 35.8% of the participants had moderate to severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy, 33.2% had moderate to severe atherosclerosis and 31.3% had arteriolosclerosis. Neocortical Lewy bodies (13.3%) and hippocampal sclerosis (10.4%) were less common.

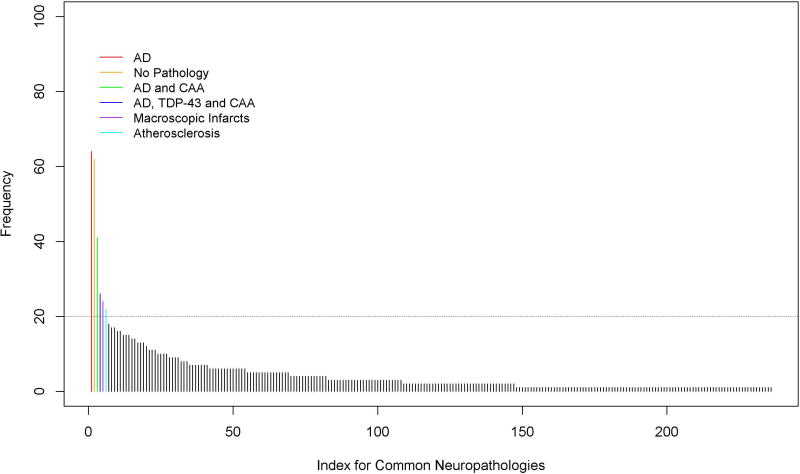

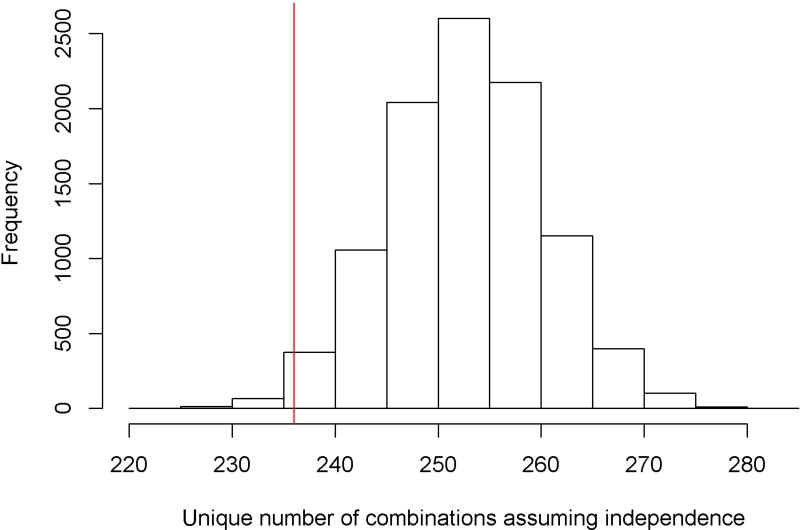

Age-related neuropathologies were frequently comorbid. Of the participants who had at least 1 neuropathology (94.3%), 77.8% had 2 or more, 58.2% had 3 or more, 35.0% had 4 or more, and 16.8% had 5 or more. Even the most frequently occurring pathology, AD, very rarely occurred in isolation (9%). Most commonly, AD was comorbid with at least one other neurodegenerative and vascular pathology (44%) or at least one vascular pathology (40%). However, individuals differed greatly with respect to their specific neuropathologic comorbidity. Surprisingly, 236 combinations of neuropathology were observed, each of which occurred in <6% of the cohort, with nearly 100 combinations present only in a single individual. Figure 1 shows the frequencies for various combinations of neuropathologies, with each bar corresponding to a single combination; a comprehensive listing of each of the specific combinations is provided in Supplementary Table 1. The neuropathologies that were most commonly present together were AD, TDP-43 and amyloid angiopathy; notably, however, these were present in combination in between 22 and 41 individuals depending on the specific combination. All other combinations were present in fewer than 20 individuals, indicating tremendous heterogeneity in neuropathologic comorbidity. To provide further context for these findings, we compared the total number of observed combinations with a simulation assuming no intercorrelation between the 9 neuropathologies. To do so, we generated 10,000 data sets, each having a sample size of N=1709. Within each set, the presence of each neuropathology was simulated as a binary random variable with the probability being the sample prevalence (Table 1). Notably, the simulated numbers of unique combinations under independent assumption had a median of 253 (interquartile range of 248–258), suggesting that the number of observed combinations (236) was close in number to that expected by chance. Figure 2 illustrates the simulation results; the vertical line shows the number of combinations observed in this dataset.

Figure 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Variable | Mean (SD) or N (percent) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age at death | 89.7 (6.5) |

|

| |

| Education | 16.1 (3.6) |

|

| |

| Female | 745 (69.1%) |

|

| |

| Baseline global cognition | −0.10 (0.62) |

|

| |

| Global cognition proximate to death | −0.84 (1.11) |

|

| |

| Final clinical diagnosis | |

| No cognitive impairment | 324 (30.5%) |

| Mild cognitive impairment | 261 (24.6%) |

| AD dementia | 459 (33.2%) |

| Other dementia | 18 (1.7%) |

|

| |

| Pathologic AD (Reagan criteria) | 704 (65.3%) |

|

| |

| Gross infarcts | 388 (36.0%) |

|

| |

| Cerebral amyloid angiopathy | |

| None | 229 (21.2%) |

| Mild | 464 (43.0%) |

| Moderate | 250 (23.2%) |

| Severe | 136 (12.6%) |

|

| |

| TDP 43 | |

| None | 496 (46.0%) |

| Inclusions in amygdala | 206 (19.1%) |

| Inclusions in amygdala and limbic regions | 218 (20.2%) |

| Inclusions in amygdala, limbic and neocortical regions | 159 (14.7%) |

|

| |

| Atherosclerosis | |

| None | 217 (20.1%) |

| Mild | 504 (46.7%) |

| Moderate | 278 (25.8%) |

| Severe | 80 (7.4%) |

|

| |

| Arteriolosclerosis | |

| None | 312 (28.9%) |

| Mild | 429 (39.8%) |

| Moderate | 253 (23.4%) |

| Severe | 85 (7.9%) |

|

| |

| Microscopic infarcts | 324 (30.0%) |

|

| |

| Cortical Lewy bodies | 143 (13.3%) |

|

| |

| Hippocampal sclerosis | 112 (10.4%) |

Figure 2.

Association of neuropathologies with cognitive loss

Using linear mixed models, we first examined the associations of the neuropathologies with longitudinal cognitive decline. With the exception of microinfarcts, all of the neuropathologies were independently associated with a lower level of cognition proximate to death and a faster rate of cognitive decline over time (Table 2). AD, the most commonly observed neuropathology, was also the most potent (i.e., had the strongest effect) when present; the less commonly observed Lewy bodies and hippocampal sclerosis followed AD with respect to potency.

Table 2.

Association of demographics and common neuropathologies with late life cognitive decline

| Variable | Cognitive level† | Rate of cognitive decline |

|---|---|---|

| Age at death | 0.003 (0.005),0.526 | 0.002 (0.0005), <0.001 |

| Female sex | 0.111 (0.070), 0.112 | 0.015 (0.007), 0.018 |

| Education | 0.037 (0.009), <0.001 | 0.001 (0.0008), 0.111 |

| AD | −0.679 (0.070), <0.001 | −0.062 (0.006), <0.001 |

| Macroscopic infarcts | −0.280 (0.069), <0.001 | −0.025 (0.006), <0.001 |

| Cerebral amyloid angiopathy | −0.265 (0.068), <0.001 | −0.018 (0.006), 0.005 |

| TDP-43 | −0.347 (0.072), <0.001 | −0.032 (0.007), <0.001 |

| Atherosclerosis | −0.281 (0.070), <0.001 | −0.021 (0.007), 0.001 |

| Arteriolosclerosis | −0.240 (0.071), <0.001 | −0.024 (0.007), <0.001 |

| Microinfarcts | −0.032 (0.070), 0.647 | 0.006 (0.006), 0.366 |

| Cortical Lewy bodies | −0.592 (0.094), <0.001 | −0.062 (0.009), <0.001 |

| Hippocampal sclerosis | −0.685 (0.110), <0.001 | −0.038 (0.010), <0.001 |

level proximate to death; statistics presented are Estimate (Standard error), p-value.

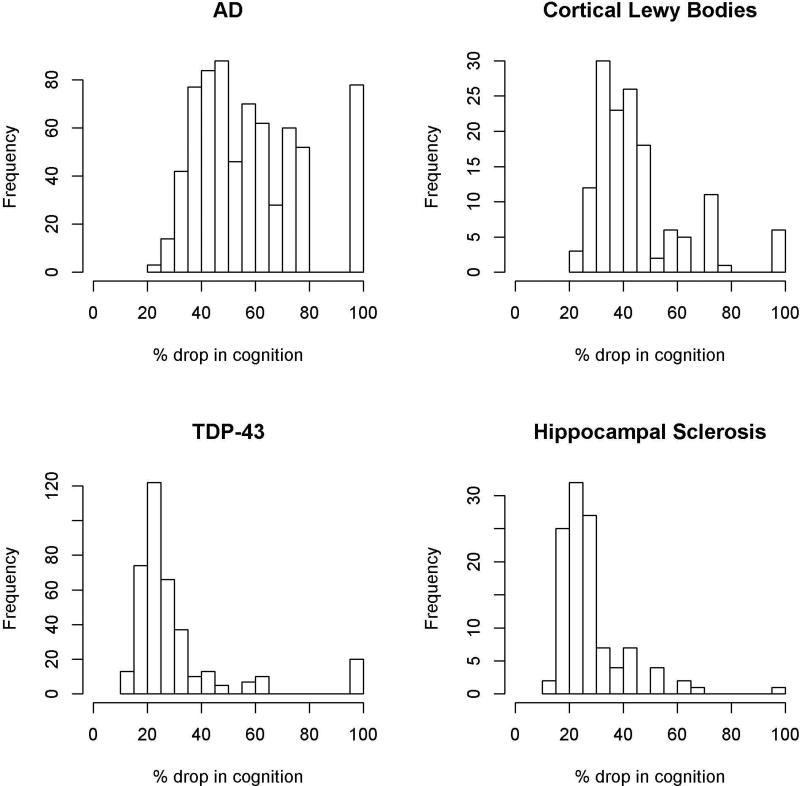

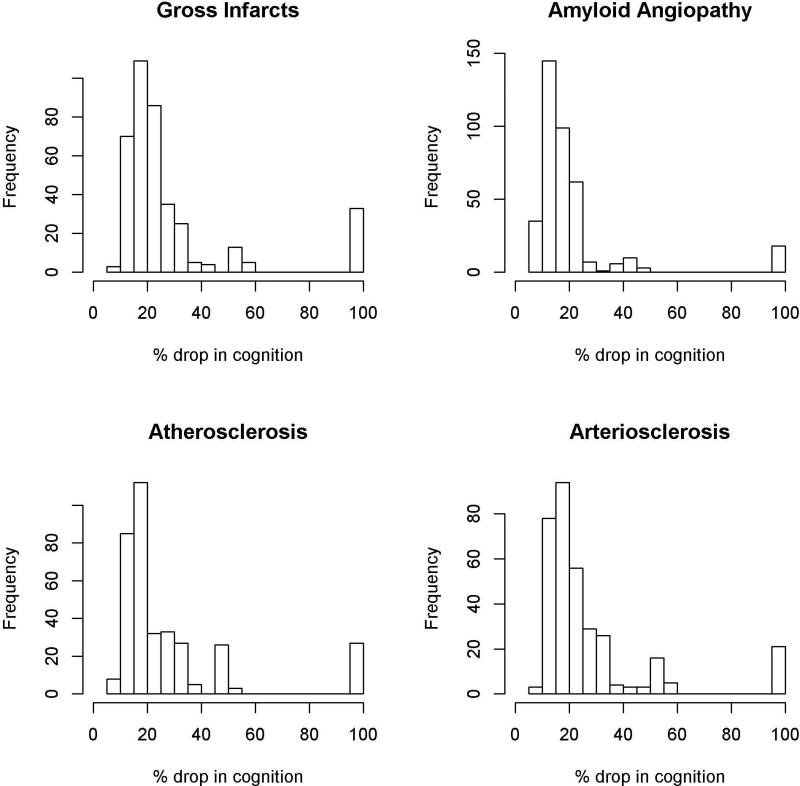

Next, for each person, we determined the proportion of the total loss of cognition accounted for by each relevant neuropathology (i.e., based on that individual’s specific combination of neuropathologies). Given that the presence of microinfarcts was not related to cognitive decline in the full model, this quantification was based on a reduced model that did not include microinfarcts. Table 3 summarizes the distribution of the proportion of cognitive loss attributable to each relevant neuropathology across individuals. As expected, the proportion of the total cognitive loss accounted for by each neuropathology differed across individuals as a result of their specific neuropathologic comorbidity.

Table 3.

Proportions of cognitive loss associated with specific neuropathologies

| N | Mean | SD | Median | Q1 | Q3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | 704 | 57.9% | 19.9% | 53.7% | 42.7% | 72.4% |

| Gross infarcts | 388 | 28.8% | 23.7% | 20.1% | 16.1% | 27.6% |

| Cerebral amyloid angiopathy | 386 | 20.6% | 19.0% | 15.7% | 11.9% | 22.1% |

| TDP 43 | 377 | 30.5% | 19.3% | 23.8% | 20.5% | 34.1% |

| Atherosclerosis | 358 | 27.4% | 23.1% | 18.5% | 14.9% | 27.7% |

| Arteriolosclerosis | 338 | 27.5% | 21.5% | 19.8% | 15.8% | 28.1% |

| Cortical Lewy bodies | 143 | 45.1% | 17.2% | 41.0% | 33.7% | 49.0% |

| Hippocampal sclerosis | 112 | 28.1% | 12.6% | 24.9% | 21.3% | 28.9% |

SD: Standard deviation; Q1 Lower Quartile; Q3 Upper Quartile

We observed interesting patterns with regard to the relative impact of specific neuropathologies on cognition. Specifically, when present, pathologic AD accounted for an average of more than 50% of the total cognitive loss (Interquartile Range (IQR): 42.7%–72.4%; Table 3). However, at a person-specific level, the relative contribution of AD varied widely, accounting for as little as 22.3% and as much as 100% of the cognitive loss depending on the other neuropathologies present (Figure 3). By contrast, although neocortical Lewy bodies and hippocampal sclerosis were much less commonly observed, when present, Lewy bodies and hippocampal sclerosis accounted for an average of 41.0% (IQR: 33.7%–49.0%) and 24.9% (IQR: 21.3%–28.9%) of the cognitive loss, respectively (Figure 3). At a person-specific level, however, their relative contributions did not range quite as dramatically as AD, mostly hovering between 20% and 50%. TDP-43 was relatively common and, when present, accounted for an average of 23.8% of the cognitive loss (IQR: 20.5%–34.1%); at a person-specific level, the contribution of TDP-43 also was more restricted than AD, mostly hovering between 15% and 35% (Figure 3). Macroscopic infarcts and other vascular pathologies were fairly common but somewhat less potent (Figure 4). Specifically, when present, macroscopic infarcts accounted for an average of 20.1% of the cognitive loss (IQR: 16.1%–27.6%), amyloid angiopathy accounted for an average of 15.7% (IQR: 11.9–22.2), atherosclerosis accounted for an average of 18.5 (IQR: 14.9–27.7), and arteriolosclerosis accounted for an average of 19.8 (IQR: 15.8–28.1). At a person-specific level, their relative contributions were fairly restricted, hovering mostly between 10% and 30%.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Finally, we performed a series of sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our findings. First, since participants with shorter follow-ups prior to death may experience a precipitous drop in cognition in the years just prior to death, we evaluated whether the findings were different if the analysis was restricted to participants with at least 4 cognitive assessments (N=943). Second, because a small percentage of the participants had a relatively long time interval between the last cognitive assessment and death, which may affect the estimation accuracy of cognitive loss, we repeated the analysis by excluding participants for whom the time interval from the last evaluation to death was more than 2 years. Third, the primary linear mixed model used time in years prior to death. To examine whether our findings were sensitive to the choice of time reference, we reran the linear mixed model by using time in years since baseline. Notably, in all of these analyses, the proportions of cognitive loss due to different neuropathologies were very similar, suggesting that our findings were robust against the length of follow-ups, the time interval between last cognitive evaluation and death, and the choice of time reference.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined neuropathologic comorbidity and quantified the person-specific contribution of nine neuropathologies to cognitive loss in more than 1000 well-characterized older persons who underwent detailed annual evaluations of cognition for up to 22 years prior to death. We found that neuropathology was ubiquitous, with nearly all participants having at least one neuropathology, more than 3/4 having two or more, more than 1/2 having 3 or more, and more than 1/3 having 4 or more. AD was the most frequent neuropathology but rarely occurred in isolation. Remarkably, more than 230 combinations of neuropathology were observed, none of which were present in >6% of the cohort. This is nearly the same number as could occur by chance. AD was the most virulent neuropathology, accounting for an average of more than 50% of the cognitive loss observed, but its relative contribution varied widely at a person-specific level, ranging from about 20% to 100% depending on the other neuropathologies present. Some less frequent neuropathologies such as neocortical Lewy bodies and hippocampal sclerosis also exerted relatively potent effects when present, accounting for an average of about 41% and 25% of the cognitive loss, respectively, but again their impacts varied at a person-specific level. Vascular pathologies were somewhat less potent, with macroscopic infarcts accounting for about 20% of the cognitive loss and amyloid angiopathy, atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis accounting for between 16–20%. These findings suggest that there is considerably greater heterogeneity in both the comorbidity and relative impact of age-related neuropathologies than currently recognized. These findings highlight an urgent need for novel approaches that embrace the heterogeneity and complexity of disease to facilitate effective strategies to combat cognitive decline in old age.

The present study expands prior work in four important ways. First, this study shows that there is remarkable neuropathologic heterogeneity in old age at the person-specific level. Although it is increasingly recognized that the brains of older persons frequently exhibit mixed neuropathology and that mixed neuropathology is the most common cause of dementia, prior studies have not examined patterns of comorbidity considering all nine of the neuropathologies studied here.1,2,4,12,13 Taking all of these diseases into account in this cohort of just over 1,000 older persons, we observed more than 230 different combinations of neuropathology. Moreover, although AD, TDP43, and CAA were the most commonly comorbid, combinations thereof were present in a surprisingly small number of persons (<45). Other combinations were even less frequent (present in <20 persons), with nearly 100 present in a single individual, indicating tremendous heterogeneity in brain aging. This heterogeneity suggests that cognitive aging is not driven by a common subset of diseases (e.g., AD plus infarcts), but rather is quite complex and multifactorial in nature.

Second, this study provides novel information regarding the relative impact of specific age-related neuropathologies on cognitive aging. This is an important advance, as prior work has not determined the person-specific contribution of neuropathologies to cognitive loss. This is in part because very few studies have the requisite sample size with longitudinal cognitive and detailed neuropathologic data to examine this issue. Not surprisingly, our results showed that AD was the most potent neuropathology, accounting for an average of half of the cognitive loss associated with the neuropathologies studied here. Surprisingly, however, the impact of AD varied widely at a person-specific level, accounting for between a fifth and all of the cognitive loss depending on the other neuropathologies present. By contrast, while neocortical Lewy bodies and hippocampal sclerosis were present only in about 10% of the cohort, they also were potent. On average, the two pathologies accounted for over a third and a quarter of the cognitive loss, respectively, but again their impacts varied at a person-specific level. Other age-related neuropathologies such as TDP43 and vascular diseases accounted for a proportion of the cognitive loss, but they were relatively less potent overall.

Third, the present findings have important implications for therapeutics, especially in the era of emerging precision medicine approaches. Currently, much of the emphasis is on finding a disease-modifying treatment for AD, particularly drugs that target amyloid. Our findings suggest that pathologic AD, when present, accounted for about 50% of the cognitive loss observed in this large cohort of older persons. This calls into question whether ongoing and planned clinical trials are adequately powered. Moreover, even if a drug that eliminated amyloid (assuming that also removes its downstream effects via tangles) were available, it would not eliminate clinical AD dementia. Clinical AD dementia is almost always the result of mixed disease. In this dataset, of the 35% of persons who did not meet criteria for pathologic AD, 21% had clinical AD dementia; further, of the 44% who had clinical AD dementia proximate to death, 17% did not meet pathologic criteria for AD. A complementary approach to amyloid studies is to identify in vivo biomarker profiles for other neuropathologies and develop therapeutics for those. Given our results showing that older persons exhibit literally hundreds of combinations of neuropathologies (with more than a third having 4 or more) and that their impacts vary widely depending on the specific combination present, one has to question whether it would be scalable or effective to provide a cocktail for each of these pathologies. These data also suggest that the effectiveness of any agent targeting a specific neuropathology or even class of neuropathologies (e.g., neurodegenerative, vascular) will vary depending on the other neuropathologies present, raising further challenges for drug development and clinical trial design. While it is possible that a common biologic pathway underlies the pathogenesis of certain related neurodegenerative diseases such as AD, TDP43, and hippocampal sclerosis, more work is needed to establish this pathway. Thus, our findings highlight an urgent need for precision medicine approaches that embrace the heterogeneity of disease and leverage an individual’s biological makeup (e.g., genetic, epigenetic, biomarker, lifestyle) to target specific biological subsets rather than broad clinical entities (i.e., AD dementia) that have multiple pathologic substrates.20

Fourth, these findings highlight a need for novel approaches to develop alternative therapeutic targets such as resilience factors.21 Importantly, our prior work showed that, when considered together, common age-related neuropathologies account for less than half of the between-subject variability in cognitive decline.4 Thus, while the present findings provide new information regarding the impact of specific neuropathologies on the proportion of cognitive decline that is driven by neuropathology, the fact that considerable variability remains unexplained suggests that the true impact of any specific neuropathology is actually much less than what was observed here. The unexplained variability is due in part to the fact that cognitive aging reflects a balance between neuropathology and resilience factors (e.g., factors that help preserve cognition agnostic of neuropathology).21 Indeed, we and others have identified many risk factors for cognitive decline and AD dementia, including experiential and genomic risk factors, most of which do not impact any known neuropathology and instead exert their effects independent of known pathologies.22–26 Thus, a potential therapeutic agent that targets resilience may support cognition even in the face of accumulating disease pathology and therefore circumvent the need for multiple cocktails. An increased focus on resilience may facilitate the identification of novel therapeutic targets that can be applied much more broadly and may have an even greater impact on cognitive outcomes than interventions targeting specific disease mechanisms.

This study has strengths and limitations. Strengths are that findings are based on a large cohort of participants recruited from the community without known dementia and who underwent detailed annual cognitive evaluations for up to 22 years, autopsy rates were very high, nine age-related neuropathologies were assessed, and the statistical approach leveraged person-specific information. The study also has limitations. One is that these analyses were based on dichotomized pathology variables. This was done in order to facilitate comparisons of the effects of different neuropathologies; however, it will be important to consider the severity of each of the different pathologies in the future in order to more precisely quantify their effects on cognition. A second limitation is that the measures of some neuropathologies are incomplete and there were additional pathologies we did not quantify (e.g., white matter disease). Finally, the findings are from a selected cohort. Future work is needed to better understand the impact of neuropathologies in population-based studies and more securely establish the degree to which they contribute to cognitive loss in old age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study came from the National Institute on Aging (R01AG34374, R01AG42210, R01AG17917, P30AG10161, R01AG15819) and the Illinois Department of Public Health

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: PAB, LY, DAB, RSW and JAS contributed to the conception and design of the study; PAB, DAB, RSW, JAS, SEL, and LY contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data; PAB and LY contributed to the drafting of the text and preparation of figures and tables; all authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript.

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.White LR, Edland SD, Hemmy LS, Montine KS, Zarow C, Sonnen JA, et al. Neuropathologic comorbidity and cognitive impairment in the Nun and Honolulu-Asia Aging Studies. Neurology. 2016;86:1000–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brayne C, Richardson K, Matthews FE, Fleming J, Hunter S, Xuereb JH, Paykel E, MukaetovaLadinska EB, Huppert FA, O'Sullivan A, Dening T. Cambridge City Over-75s Cohort Cc75c Study Neuropathology Collaboration. Neuropathological correlates of dementia in over-80-year old brain donors from the population-based Cambridge city over-75s cohort (CC75C) study. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2009;18:645–658. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Relation of cerebral vessel disease to Alzheimer's disease dementia and cognitive function in elderly people: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet Neurology. 2016;15:934–43. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30029-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Yu L, Barr AM, Honer WG, Schneider JA, et al. Much of late life cognitive decline is not due to common neurodegenerative pathologies. Annals of Neurology. 2013;74:478–89. doi: 10.1002/ana.23964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle PA, Yu L, Nag S, Leurgans S, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cognitive outcomes in community-based older persons. Neurology. 2015;85:1930–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson PT, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Kryscio RJ, Jicha GA, Smith CD, et al. Modeling the association between 43 different clinical and pathological variables and the severity of cognitive impairment in a large autopsy cohort of elderly persons. Brain Pathology. 2010;20:66–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson PT, Schmitt FA, Lin Y, Abner EL, Jicha GA, Patel E, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis in advanced age: clinical and pathological features. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 5):1506–18. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson RS, Yu L, Trojanowski JQ, Chen EY, Boyle PA, Bennett DA, et al. TDP-43 pathology, cognitive decline, and dementia in old age. JAMA Neurology. 2013;70:1418–24. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. The neuropathology of probable Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Annals of Neurology. 2009;66:200–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.21706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dodge HH, Zhu J, Woltjer R, et al. SMART data consortium. Risk of incident clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease-type dementia attributable to pathology-confirmed vascular disease. Alzheimers and Dementia. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.11.003. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.James BD, Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Trojanowski JQ, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. TDP-43 stage, mixed pathologies, and clinical Alzheimer's-type dementia. Brain. 2016;139:2983–93. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69:2197–204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapasi A, DeCarli C, Schneider JA. Impact of multiple pathologies on the threshold for clinically overt dementia. Acta Neuropathologica. 2017;134:171–86. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1717-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Schneider JA. Relation of neuropathology to cognition in persons without cognitive impairment. Annals of Neurology. 2012c;72:599–609. doi: 10.1002/ana.23654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyle PA, Yu L, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Relation of neuropathology with cognitive decline among older persons without dementia. Frontiers in Aging and Neuroscience. 2013;5:50. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the religious orders study. Current Alzheimer’s Research. 2012;9:628–45. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the rush Memory and Aging Project. Current Alzheimer’s Research. 2012;9:646–63. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson RS, Beckett LA, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Bach J, Evans DA, et al. Individual differences in rates of change in cognitive abilities of older persons. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17:179–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nag S, Yu L, Capuano AW, Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis and TDP-43 pathology in aging and Alzheimer disease. Annals of Neurology. 2015;77:942–52. doi: 10.1002/ana.24388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cholerton B, Larson EB, Quinn JF, et al. Precision Medicine: Clarity for the Complexity of Dementia. The American Journal of Pathology. 2016;186(3):500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett DA. Mixed pathologies and neural reserve: Implications of complexity for Alzheimer disease drug discovery. PLoS Med. 2017:14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Yu L, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Life-span cognitive activity, neuropathologic burden, and cognitive aging. Neurology. 2013;81:314–21. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829c5e8a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu L, Lutz MW, Farfel JM, Wilson RS, Burns DK, Saunders AM, De Jager PL, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Neuropathologic features of TOMM40 '523 variant on late-life cognitive decline. Alzheimers and Dementia. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.05.002. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson RS, Nag S, Boyle PA, Hizel LP, Yu L, Buchman AS, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Neural reserve, neuronal density in the locus ceruleus, and cognitive decline. Neurology. 2013;80:1202–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182897103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett DA, Arnold SE, Valenzuela MJ, Brayne C, Schneider JA. Cognitive and Social Lifestyle: Links with Neuropathology and Cognition in Late Life. Acta neuropathologica. 2014;127(1):137–150. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1226-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buchman AS, Yu L, Boyle PA, Schneider JA, DeJager PL, Bennett DA. Higher brain BDNF gene expression is associated with slower cognitive decline in older adults. Neurology. 2016;86:735–41. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.