Abstract

This survey examines knowledge of the association of human papillomavirus and head and neck cancer among students at 10 New York State medical schools.

Millions of Americans are infected with human papillomavirus (HPV), with rates of HPV-positive head and neck cancer (HNC) expected to surpass cervical cancer by 2020. Nevertheless, most adults are not aware of associations between HPV and HNC. Although debate surrounds HPV vaccine efficacy against these cancers, one trial demonstrated that the vaccine prevents 93.3% of prevalent oral HPV infections. This has the potential to reduce HNC burden if paired with high vaccine uptake, but only 60% of US teens have initiated the HPV series. Strong recommendations for vaccination are linked to increased HPV vaccine uptake; thus, physicians must be educated about the association between HPV and HNC. Studies suggest that only 47% of pediatricians routinely discuss HPV-positive HNC owing to a self-reported lack of knowledge. It becomes imperative to examine how we are training our next generation of physicians regarding this epidemic. We examined knowledge about HPV-positive cancer among New York State medical students to determine whether there is an educational gap in HNC knowledge.

Methods

A survey administered through REDCap (https://projectredcap.org) collected information on level of training, objective HPV-positive cancer knowledge, and self-assessment of knowledge. Surveys were sent to medical students at 10 medical schools in New York State via representatives at each institution, with 1 reminder email sent to each representative. Because we did not track responses by school or official distribution by representatives, we could not determine response rates. Objective knowledge was assessed using 2 knowledge-based questions. Self-assessment of knowledge was obtained using a 5-point Likert scale, from 1, representing no knowledge, to 5, representing excellent knowledge, and presented as mean (SD). Data were analyzed with SPSS statistical software version 21.0.0.0 (IBM Corp). Proportional differences were assessed using the phi coefficient (φ) and differences in Likert scores using the Cohen d statistic with 95% CIs. This study was deemed exempt from formal review or the need for informed participant consent by the institutional review board of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

Results

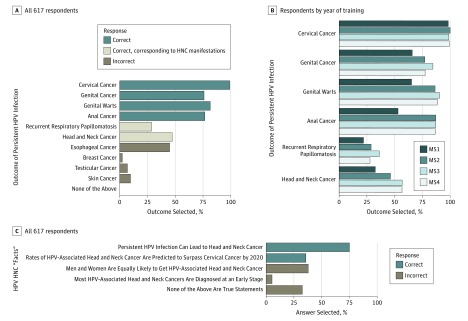

Seven hundred seven medical students initiated the survey and 617 completed it. Of those who completed the survey, 187 (30.3%) were in their first year of training (MS1), 132 (21.4%) were MS2, 169 (27.4%) were MS3, and 129 (20.9%) were MS4. Six hundred eleven students (99.0%) correctly identified associations between persistent HPV infection and cervical cancer, whereas 468 (75.9%) associated HPV with genital cancers, 503 (81.5%) with genital warts, and 473 (76.7%) with anal cancer. Fewer students correctly selected recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP) (176 students [28.5%]) or HNC (291 [47.2%]) than selected cervical cancer (φ = 0.733 for RRP; φ = 0.585 for HNC), with selection rates similar to incorrect responses such as esophageal cancer (n = 277 [44.9%]; φ = 0.023 vs HNC; φ = 0.170 vs RRP) (all responses shown in Figure 1A with year of training breakdown in Figure 1B). Rates of HNC selection increased slightly as medical school progressed (MS1, 61 of 187 [32.6%]; MS4, 73 of 129 [56.6%]; φ = 0.238). In contrast, rates of cervical cancer selection remained high throughout training (MS1, 184 of 187 [98.4%]; MS4, 128 of 129 [99.2%]; φ = 0.036). Selection rates for the veracity of HPV-positive HNC facts are presented in Figure 1C.

Figure 1. Objective Knowledge of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)–Positive Cancers.

A and B, Outcomes selected by all 617 students and by students according to their year of training in response to the question, “Persistent HPV infection can lead to which of the following?” C, Answers selected by all 617 students in response to the request, “From the list below, please indicate which of the following are true statements.” HNC indicates head and neck cancer; MS1, MS2, MS3, and MS4, first, second, third, and fourth year of medical school, respectively.

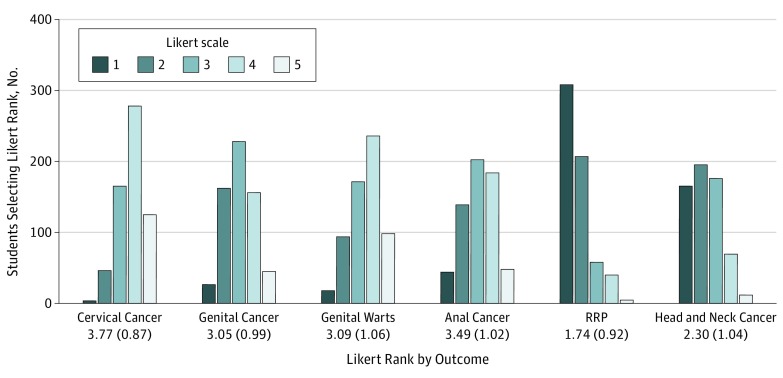

Compared with cervical cancer, self-reported knowledge scores were lower for HNC (mean difference, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.36-1.58; Cohen d = 1.53) and RRP (mean difference, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.93-2.12; Cohen d = 2.27). The magnitude of difference was smaller compared with the next highest reported score, anal cancer (mean difference vs HNC, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.07-1.31; Cohen d = 1.15; mean difference vs RRP, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.64-1.85; Cohen d = 1.75). Likert data are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Self-reported Knowledge on Human Papillomavirus–Associated Cancers.

Knowledge was ranked on a Likert scale, with 1 representing no knowledge and 5, excellent knowledge. Mean (SD) Likert rankings are given for each possible outcome. RRP indicates recurrent respiratory papillomatosis.

Discussion

Our data suggest an educational gap about HPV-positive cancers among medical students. Despite clear awareness of cervical cancer risks, fewer students are aware of HPV’s head and neck manifestations. Only about half of medical students graduate with knowledge about this association. Although this study is limited by its low response rate (617 students) relative to the total number of medical students in New York state, this education gap may be generalizable to students nationally. To increase HPV vaccination rates and have an impact on the future of this epidemic, physicians must be informed; thus, head and neck manifestations of persistent HPV infection should be emphasized in medical school curricula.

References

- 1.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4294-4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luryi AL, Yarbrough WG, Niccolai LM, et al. Public awareness of head and neck cancers: a cross-sectional survey. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(7):639-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrero R, Quint W, Hildesheim A, et al. ; CVT Vaccine Group . Reduced prevalence of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 years after bivalent HPV vaccination in a randomized clinical trial in Costa Rica. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;662017:874-882. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6633a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohammed KA, Vivian E, Loux TM, Arnold LD. Factors associated with parents’ intent to vaccinate adolescents for human papillomavirus: findings from the 2014 National Immunization Survey–Teen. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14(E45):1-12. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):pii: e20161764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gnagi SH, Gnagi FT, Schraff SA, Hinni ML. Human papillomavirus vaccination counseling in pediatric training: are we discussing otolaryngology-related manifestations? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155(1):87-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]