This cohort study investigates racial differences in longitudinal visual field variability and their impact on time to detect visual field progression.

Key Points

Question

Are there racial differences in visual field variability over time?

Findings

In a cohort study, individuals of African descent with glaucoma showed a larger variability in standard automated perimetry results, as well as increased times to detect progression on computer simulated analyses, compared with individuals of European descent.

Meaning

Increased visual field variability in glaucomatous eyes in individuals of African descent may result in delayed detection of progression that could potentially contribute to explain higher rates of glaucoma-related visual impairment in this population.

Abstract

Importance

Individuals of African descent have been reported to be at higher risk for becoming visually impaired from glaucoma compared with individuals of European descent.

Objective

To investigate racial differences in longitudinal visual field variability and their impact on time to detect visual field progression.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter prospective observational cohort study included 236 eyes of 173 individuals of European descent and 235 eyes of 171 individuals of African descent followed up for a mean (SD) time of 7.5 (3.4) years.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Differences in test-retest variability and simulated time to detect progression in individuals of African descent and of European descent with glaucoma. Standard automated perimetry mean deviation values were regressed over time for each eye, and SD of the residuals was used as a measure of variability. Distributions of residuals were used in computer simulations to reconstruct “real-world” standard automated perimetry mean deviation trajectories under different assumptions about rate of change and frequency of testing. Times to detect progression were obtained for the simulated visual fields.

Results

Among the 344 patients, the mean (SD) age at baseline was 60.2 (10.0) and 60.6 (9.0) years for individuals of African descent and of European descent, respectively; 94 (52%) and 86 (48%) of individuals of African descent and of European descent were women, respectively. The mean SD of the residuals was larger in eyes of individuals of African descent vs those of European descent (1.45 [0.83] dB vs 1.12 [0.48] dB; mean difference: 0.33 dB; 95% CI of the difference, 0.21-0.46; P < .001). The eyes in individuals of African descent had a larger increase in variability with worsening disease (P < .001). When simulations were performed assuming common progression scenarios, there was a delay to detect progression in eyes of individuals of African descent compared with those of European descent. For a scenario with baseline mean deviation of –10 dB and rate of change of –0.5 dB/y, detection of progression in individuals of African descent was delayed by 3.1 (95% CI, 2.9-3.2) years, when considered 80% power and annual tests.

Conclusions and Relevance

Patients of African descent with glaucoma showed increased visual field variability compared with those of European descent, resulting in delayed detection of progression that may contribute to explain higher rates of glaucoma-related visual impairment in individuals of African descent compared with those of European descent with glaucoma.

Introduction

Glaucoma is a leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide. Population-based studies have shown that the prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma is higher in individuals of African descent compared with those of European descent. In addition to being more prevalent, glaucoma may cause a disproportionally higher rate of functional impairment in individuals of African descent.

The reasons for the higher incidence of functional impairment from glaucoma in individuals of African descent have not been well clarified. Previous studies suggest that glaucoma tends to occur at an earlier age and present with more extensive damage at diagnosis in individuals of African descent compared with those of European descent. It has also been suggested that the disease may progress at a faster rate in individuals of African descent, who may have lower adherence rates.

Standard automated perimetry (SAP) remains the reference test for assessment of functional loss in glaucoma and is still the most widely used method to detect progression of visual field damage. However, SAP is disadvantaged from considerable test-retest variability. Such variability can hinder detection of change, as detection of progression depends on the ability to separate true change (the signal) from test-retest variability (the noise). In the presence of large test-retest variability, significant changes can be missed and lead to delayed initiation or escalation of treatment.

If racial differences exist in visual field variability, this could influence the ability to detect progression with SAP in individuals of African descent and of European descent with glaucoma. To our knowledge, differences in visual field variability by race have not been previously investigated. We hypothesized that increased visual field variability in individuals of African descent may result in delayed detection of progression in this group, potentially leading to delayed treatment and offering an additional or alternative explanation for the increased risk for functional impairment previously reported in this group.

The purpose of this study was to investigate differences in test-retest SAP variability in a large cohort of individuals of African descent and of European descent with glaucoma followed up over time. We also investigated the impact of differences in visual field variability in the time to detect progression in the 2 racial groups by use of computer simulation.

Methods

Individuals were enrolled from the Diagnostic Innovations in Glaucoma Study and the African Descent and Glaucoma Evaluation Study. The study collaboration included the Hamilton Glaucoma Center, University of California, San Diego; Edward S. Harkness Eye Institute, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York; and Department of Ophthalmology, University of Alabama at Birmingham. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and methods adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. All 3 institutions provided institutional review board approval.

At each annual visit during follow-up, patients underwent a comprehensive ophthalmologic examination that included review of medical history, best-corrected visual acuity, slitlamp biomicroscopy, Goldmann tonometry, dilated ophthalmoscopic examination, stereoscopic optic disc photograph (Kowa Nonmyd WX3D; Kowa Optimed, Inc), and SAP using the Swedish interactive threshold algorithm standard 24-2 test (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc). Individuals were excluded if they had any ocular or systemic disease that could affect the optic nerve or the visual field.

All patients had the diagnosis of primary open-angle glaucoma at baseline based on the presence of repeatable (at least 3 consecutive) abnormal SAP test results with associated glaucomatous appearance of the optic disc. Abnormal SAP was defined as a pattern standard deviation with P < .05 and/or glaucoma hemifield test results outside normal limits. Optic disc damage was evaluated by masked assessment of stereophotographs. Glaucomatous optic disc appearance was defined based on the presence of neuroretinal rim thinning, excavation, notching, or characteristic retinal nerve fiber layer defects. For inclusion in the analyses, each eye was required to have had at least 5 SAP tests over a follow-up duration of at least 2 years with 6-month intervals between the visits.

Standard Automated Perimetry

Visual fields were performed using SAP Swedish interactive threshold algorithm 24-2. Visual fields were excluded if they had more than 33% fixation losses or more than 15% false-positive errors. Visual fields were excluded in the presence of the following artifacts: eyelid, rim artifacts, fatigue effects, inappropriate fixation, evidence that the visual field results were caused by a disease other than glaucoma, or inattention. Visual fields exhibiting a learning effect (ie, initial test results showing consistent improvement on visual field indices) were excluded.

Socioeconomic Variables

Information on socioeconomic variables was also collected by self-reported questionnaire for all patients. The questionnaire contained degree of education (at least high school degree [yes/no]), marital status (married [yes/no]), health insurance coverage (yes/no), and income (less than $25 000 per year [yes/no]).

Data Analysis

Ordinary least squares linear regression models of SAP mean deviation (MD) over time were fit to the sequence of visual field tests for each eye in individuals of African descent and of European descent. The residuals from the trend lines were calculated, and the SD of the residuals was used as a measure of variability. The SD of the residuals was compared between the 2 racial groups using a Wilcoxon rank sum test. Subsequently, we evaluated the association of race with the SD of the residuals in a multivariable model adjusting for average MD during the follow-up period, age, and duration of follow-up. As the association between variability and visual field sensitivity is nonlinear, it was modeled using restricted cubic splines, with the number of knots determined by cross-validation. We investigated whether the association of race with the SD of the residuals depended on visual field sensitivity by including second-order interaction terms between race and splines representing average MD.

Next, we used computer simulations to estimate time to detect visual field progression in both racial groups. The ordinary least squares residuals of MD trends over time obtained from the original cohort were binned according to the fitted levels of MD. Empirical distributions of residuals were then available for each level of MD, allowing reconstruction of MD trajectories over time by computer simulation, according to expected “true” rates of glaucoma progression. A similar approach has been described previously by Russell et al. Given a “true” MD value, the empirical distributions of MD residuals contain the range of measured values that would be expected for a given test. Longitudinal sequences of visual field tests were then simulated by assuming a “true” baseline MD and a “true” rate of change and then sampling from the empirical distributions of residuals to reconstruct what the test MD would be at each time. For example, assuming a “true” baseline MD of –5 dB and an annual rate of change of –1 dB/y, “true” MD measurements would be –5, –6, –7, –8, and –9 dB in the first 4 years of follow-up. However, visual field data are affected by noise, which in our simulations was added to the “true” values by sampling from the empirical distributions of residuals for each corresponding level of MD. For example, one of the simulated visual fields for this situation had MD values of –5.3, –4.9, –7.5, –8.6, and –7.9 dB for the first 4 years of follow-up. Visual field data were simulated for each racial group, taking into account race-specific empirical distributions of residuals. We simulated 10 000 sequences of visual fields for each racial group, assuming equivalent fixed-test intervals for each racial group. We then obtained the earliest time to detect progression for each sequence of visual fields in each racial group. Progression was defined as a statistically significant negative slope of MD over time with P < .05. This allowed us to construct cumulative probability functions of time to detect progression for each racial group and estimate differences in time to detect progression under specific visual field scenarios. All statistical analyses were performed with commercially available software (Stata, version 14 [StataCorp] and MatLab, version R2016a [MathWorks]). The α level (type I error) was set at .05.

Results

The study included a total of 471 eyes of 344 patients followed up for a mean (SD) of 7.5 (3.4) years with a mean (SD) number of 13.4 (6.3) visual field tests. From the 471 eyes, 235 eyes (49.9%) were from 171 individuals of African descent, and 236 eyes (50.1%) were from 173 individuals of European descent. Table 1 shows demographic and clinical characteristics of included individuals from the 2 groups. There was no difference between the number of field tests during follow-up in individuals of African descent and of European descent (mean [SD], 13.6 [6.1] vs 13.2 [6.4], respectively; P = .46). Seventy-two eyes (31%) were detected as progressing in individuals of African descent vs 95 (40%) in individuals of European descent (P = .03). There was no difference in average rate of change in progressing eyes for individuals of African descent and of European descent (mean [SD], –0.60 [0.64] dB/y vs –0.61 [0.54] dB/y, respectively; P = .91).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Patients.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| African Descent | European Descent | |

| Total eyes | 235 | 236 |

| Total patients | 171 | 173 |

| Age, y | 60.0 (10.6) | 60.8 (9.1) |

| Women, No. (%) | 55 (32.2) | 50 (28.9) |

| Baseline SAP MD 24-2, dB | −6.5 (6.7) | −6.4 (5.5) |

| Baseline SAP PSD 24-2, dB | 5.5 (3.7) | 6.9 (4.0) |

| Baseline IOP, mm Hg | 17.4 (5.2) | 19.4 (7.4) |

| Baseline RNFL thickness, μm | 78.9 (17.5) | 74.1 (15.5) |

| Progressing eyes, % | 31 (13.2) | 40 (16.9) |

| Rate of change in progressing eyes, dB/y | −0.6 (0.6) | −0.6 (0.5) |

| Follow-up time, y | 8.6 (0.2) | 6.4 (0.3) |

| No. of tests | 13.6 (6.1) | 13.2 (6.4) |

| Education level (at least high school degree), No. (%) | 67 (39.2) | 83 (48.0) |

| Income (>$25 000), No. (%) | 69 (40.4) | 88 (50.9) |

| Marital status (married), No. (%) | 33 (19.3) | 68 (39.3) |

| Insurance (yes), No. (%) | 92 (53.8) | 92 (53.2) |

Abbreviations: IOP, intraocular pressure; MD, mean deviation; PSD, pattern standard deviation; RNFL, retinal nerve fiber layer; SAP, standard automated perimetry.

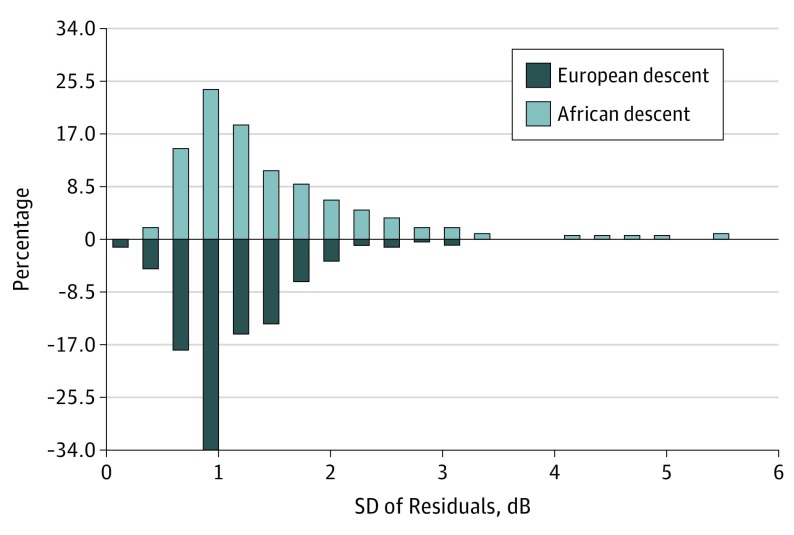

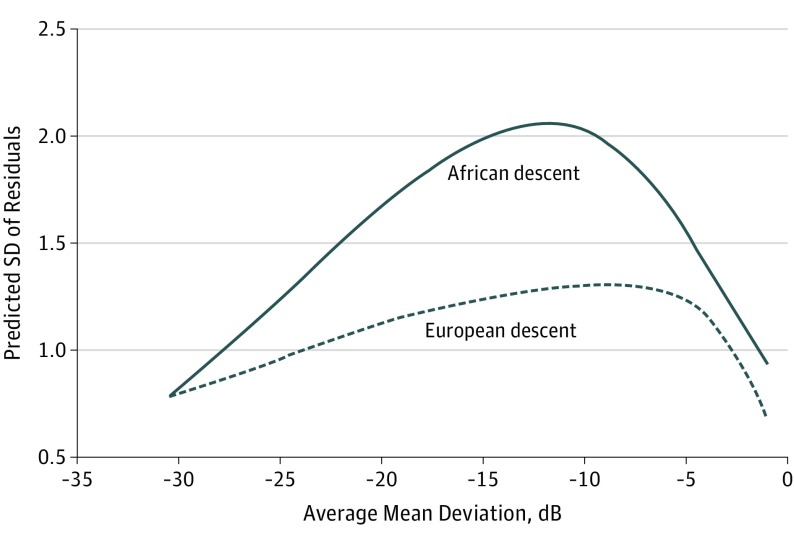

The average SD of the residuals was larger in the individuals of African descent vs those of European descent (mean [SD], 1.45 [0.83] dB vs 1.12 [0.48] dB; mean difference, 0.33 dB; 95% CI, 0.21- 0.46; P < .001), with greater visual field variability over time in eyes of individuals of African descent. Figure 1 shows a histogram of SD of the residuals for the 2 groups. Table 2 shows the multivariable model investigating the association of race with visual field variability adjusted for disease severity (average MD during follow-up), age, and duration of follow-up. Race was associated with visual field variability (P < .001, joint Wald test). Worse visual field damage was also associated with increased variability (P < .001, joint Wald test). The nonlinear association was modeled by splines (Figure 2). There was an interaction between race and disease severity to determine visual field variability. This can be seen in Table 2 by the coefficients associated with the interaction terms between race and MD splines (P < .001; joint Wald test for interaction terms). The difference in visual field variability between individuals of African descent and of European descent initially increased with worse visual field damage but then decreased as the visual field damage became advanced. The greatest difference between the 2 groups was seen at an MD of approximately –12 dB.

Figure 1. Distribution of the SD of the Residuals in European and African Descent Groups.

Table 2. Results of Multivariable Regression Model Evaluating the Association of Race With Visual Field Variability (SD of Residuals) Adjusting for Covariates.

| Parameter | Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals of African descent | 1.911 (1.014 to 2.808) | <.001 |

| SAP MD spline 1, per 1 dB lower | 0.030 (−0.010 to 0.069) | .14 |

| SAP MD spline 2, per 1 dB lower | −0.029 (−0.076 to 0.019) | .24 |

| SAP MD spline 3, per 1 dB lower | −1.249 (−3.151 to 0.654) | .20 |

| Race × SAP MD spline 1 | 0.063 (0.014 to 0.111) | .01 |

| Race × SAP MD spline 2 | −0.119 (−0.184 to −0.054) | <.001 |

| Race × SAP MD spline 3 | 3.163 (0.473 to 5.583) | .02 |

| Age, per 1 y older | −0.002 (−0.008 to 0.004) | .48 |

| Follow-up duration, per 1 y | 0.094 (0.031 to 0.158) | .004 |

Abbreviations: MD, mean deviation; SAP, standard automated perimetry.

Figure 2. Association Between Visual Field Variability and Visual Field Severity.

The nonlinear association between visual field variability and visual field severity modeled by splines in European and African descent groups. The main difference between the 2 groups was seen at mean deviation of approximately –12 dB.

The eTable in the Supplement shows the multivariable model investigating the association of race with visual field variability adjusted for disease severity (average MD during follow-up), age, duration of follow-up, and socioeconomic variables. Race was significantly associated with visual field variability (P < .001) even adjusted for socioeconomic data.

From data on visual field variability of the 2 groups, we simulated a variety of scenarios to estimate the difference in time to detect progression between patients of African descent and of European descent. We assumed baseline MD values of –5 dB and –10 dB and true rates of MD change of –0.25 dB/y (slow), –0.5 dB/y (moderate), and –1 dB/y (fast), with annual testing. Table 3 reports mean predicted times to detect progression as well as predicted times to detect progression to achieve 80% power (when 80% of the progressing eyes would be detected as progressing). Individuals of African descent had longer times to detect progression than those of European descent. For the scenario of a baseline MD of –10 dB, true rate of progression of –0.5 dB/y, and annual testing, it would take 11.4 years to detect 80% of progressing eyes of individuals of African descent vs 8.3 years to detect 80% of progressing eyes of those with European descent, with a mean difference of 3.1 years.

Table 3. Time to Detect Progression According to Different Scenarios of Visual Field Loss Over Time in Eyes of Individuals of African Descent and for Those of European Descent and Assuming Annual Testing.

| Baseline Disease Severity, dB | “True” Rate of Change, dB/y | Mean Time to Detect Progression, Mean (SD), y | Time to Detect Progression in 80% of Eyes (80% Power), y | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Descent | African Descent | European Descent | African Descent | ||

| −5 | −0.25 | 9.5 (4.0) | 11.2 (4.9) | 13.1 | 15.6 |

| −0.5 | 6.5 (2.4) | 7.6 (3.0) | 8.6 | 10.3 | |

| −1.0 | 4.6 (1.5) | 5.2 (1.8) | 5.9 | 6.9 | |

| −10 | −0.25 | 9.4 (3.5) | 12.5 (5.8) | 12.6 | 17.7 |

| −0.5 | 6.4 (2.1) | 8.6 (3.3) | 8.3 | 11.4 | |

| −1.0 | 4.5 (1.4) | 5.9 (2.1) | 5.7 | 7.7 | |

Discussion

In the current study, we demonstrated that patients of African descent with glaucoma show larger visual field variability over time compared with individuals of European descent. To our knowledge, this is the first study to suggest the existence of racial differences in visual field variability, which could potentially affect the ability to detect glaucomatous change over time. Our findings may have significant implications to establish strategies for monitoring disease progression.

Test-retest variability may significantly affect the ability to detect change over time. In our study, test-retest variability was estimated by the SDs of residuals, which were on average approximately 30% larger in individuals of African descent vs those of European descent. A previous study suggested that SAP variability must be reduced by approximately 20% for a clinically appreciable improvement in detection of visual field change. Therefore, using a similar reasoning, an increase of 30% in variability would likely result in a clinically appreciable worsening in the ability to detect visual field change in individuals of African descent. Of note, racial differences in variability were more pronounced for MD values close to –10 dB, which was the result of a significant interaction between race and visual field severity in explaining levels of variability (Figure 2). This is an especially important result, as at these levels of damage any further visual field worsening could significantly compromise quality of life.

We performed computer simulations to investigate the impact of increased variability on the time to detect progression. Assuming a common progression scenario with a baseline MD of –10 dB and rate of change of –0.5 dB/y, there was a difference of 3.1 years in the time to detect progression in eyes of individuals with African descent vs those of European descent, assuming 80% power and annual testing. Even with faster rates of change of –1 dB/y, there was still a 2-year lag in detecting change between the 2 groups. Moreover, previous studies have suggested that patients of African descent actually get less frequent visual field testing in clinical practice. For example, Ostermann et al found that patients of African descent with glaucoma were 32% less likely to undergo an eye examination during the year compared with those of European descent. Wang et al showed that Medicare beneficiaries of African descent were only 67% as likely as their counterparts of European descent to use eye care services. Therefore, it is likely that the frequency of visual field examinations in patients of African descent with glaucoma may be lower than in those of European descent, which would magnify the differences in time to detect progression found in our study. Delayed detection of progression could result in late initiation/escalation of treatment and irreversible functional loss. In addition, delayed detection could lead to loss of follow-up by giving a false sense of security to patients that the condition has not been progressing and no follow-up is needed. Large variability may also result in an increase in the number of visual fields declared as progression when in fact no true change has occurred. These false positives may lead to unnecessary escalation of treatment with potential adverse effects to patients.

The reasons for the larger visual field variability found in individuals of African descent are not clear. We conducted separate analysis by site, and race was still associated with visual field variability for each site: San Diego (1.24 dB; 95% CI, 0.93-1.55; P < .001), Alabama (2.44 dB, 95% CI, 1.74-3.14; P < .001), and New York (0.95 dB; 95% CI, 0.28-1.62; P = .006). Therefore, it is unlikely that our results could be explained by site differences. Differences in socioeconomic or educational background could potentially affect visual field variability. In our sample, individuals of African descent had a lower mean income and lower mean educational level compared with those of European descent. However, the association of race with visual field variability was still present even after adjustment for these factors. It should be noted, however, that socioeconomic variables were obtained by self-reported questionnaires and may be subject to reporting biases. In addition, it is possible that the measured variables might not have fully captured other existing socioeconomic differences between the 2 groups. A 2017 study by Diniz-Filho et al concluded that cognitive decline was associated with increased visual field variability over time. Although we were not able to assess overall cognitive status in the individuals enrolled in the current study, the association between cognitive decline and race in the literature has been controversial. As another potential reason for the differences in variability, it is possible that technician supervision while performing perimetry may have differed between the 2 groups. Although patients were all part of a prospective longitudinal study with a rigorous protocol for testing, differences may still have existed, which would be difficult to quantify.

Regardless of the underlying reason for the increased variability found in individuals of African descent, it is likely that the differences found in our study represent realistic scenarios found in clinical practice. Although the differences in variability found in our study are most likely due to uncontrolled covariates rather than a direct racial effect per se, it is likely that in practice, such scenarios are present at a similar, if not worse, degree. Therefore, clinicians may need to increase the frequency of testing to obtain more precise estimates of indices of change over time or use complementary tests for assessment of progression, such as structural imaging of the optic nerve, nerve fiber layer, or macula. Alternatively, methods combining structural and functional tests may also be helpful.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. Assessment of visual field variability and progression was based solely on investigation of trend analysis of MD over time. There are other methods available to detect visual field changes, which rely on assessment of localized losses and also on event-based approaches. It is possible that the impact of variability on times to detect progression would be different by these methods. However, it is likely that the effects of increased variability would be even higher in assessing localized losses compared with a global index such as MD. As another limitation of our study, the classification of race was based on self-reported assessment by the study individuals. The term race is complex and may represent a large biodiversity of cultural, geographic, biological, and socioeconomic characteristics. However, it has been shown that studies using “self-described race” are useful as long as this information can be obtained in a standardized manner. In addition, it has been shown that “self-described race” has a good correlation with measures of racial classification using genetic admixture techniques.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrated that individuals of African descent with glaucoma have increased longitudinal visual field variability compared with individuals of European descent with the disease. The increased variability may lead to delayed detection of progression and possible delayed intervention, which could explain in part the higher incidence of glaucoma-related visual impairment in individuals of African descent compared with those of European descent.

eTable. Results of Multivariable Regression Model Evaluating the Effect of Race on Visual Field Variability (SD of Residuals) Adjusting for Covariates and Socioeconomic Variables

References

- 1.Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1901-1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson R, Richardson TM, Hertzmark E, Grant WM. Race as a risk factor for progressive glaucomatous damage. Ann Ophthalmol. 1985;17(10):653-659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tielsch JM, Sommer A, Katz J, Royall RM, Quigley HA, Javitt J. Racial variations in the prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma: the Baltimore Eye Survey. JAMA. 1991;266(3):369-374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosoko-Lasaki O, Gong G, Haynatzki G, Wilson MR. Race, ethnicity and prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(10):1626-1629. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leske MC, Connell AM, Schachat AP, Hyman L. The Barbados Eye Study: prevalence of open angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112(6):821-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson MR. Glaucoma in blacks: where do we go from here? JAMA. 1989;261(2):281-282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiller R, Kahn HA. Blindness from glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;80(1):62-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muñoz B, West SK, Rubin GS, et al. . Causes of blindness and visual impairment in a population of older Americans: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(6):819-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin MJ, Sommer A, Gold EB, Diamond EL. Race and primary open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99(4):383-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glaucoma Laser Trial (GLT): 5: subgroup differences at enrollment. Ophthalmic Surg. 1993;24(4):232-240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant WM, Burke JF Jr. Why do some people go blind from glaucoma? Ophthalmology. 1982;89(9):991-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilensky JT, Gandhi N, Pan T. Racial influences in open-angle glaucoma. Ann Ophthalmol. 1978;10(10):1398-1402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenidge KC, Dweck M. Glaucoma in the black population: a problem of blindness. J Natl Med Assoc. 1988;80(12):1305-1309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flammer J, Drance SM, Zulauf M. Differential light threshold: short- and long-term fluctuation in patients with glaucoma, normal controls, and patients with suspected glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102(5):704-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flammer J, Drance SM, Fankhauser F, Augustiny L. Differential light threshold in automated static perimetry: factors influencing short-term fluctuation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102(6):876-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flammer J, Drance SM, Augustiny L, Funkhouser A. Quantification of glaucomatous visual field defects with automated perimetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985;26(2):176-181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heijl A, Lindgren G, Olsson J. Normal variability of static perimetric threshold values across the central visual field. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105(11):1544-1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flammer J, Drance SM, Schulzer M. Covariates of the long-term fluctuation of the differential light threshold. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102(6):880-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz J, Sommer A. A longitudinal study of the age-adjusted variability of automated visual fields. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105(8):1083-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Racette L, Liebmann JM, Girkin CA, et al. ; ADAGES Group . African Descent and Glaucoma Evaluation Study (ADAGES): III: ancestry differences in visual function in healthy eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(5):551-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sample PA, Girkin CA, Zangwill LM, et al. ; African Descent and Glaucoma Evaluation Study Group . The African Descent and Glaucoma Evaluation Study (ADAGES): design and baseline data. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(9):1136-1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruse A, Lim L. Cubic splines as a special case of restricted least squares. J Am Stat Assoc. 1977;72:64-68. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith PL. Splines as a useful and convenient statistical tool. Am Stat. 1979;33:57-62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell RA, Garway-Heath DF, Crabb DP. New insights into measurement variability in glaucomatous visual fields from computer modelling. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russell RA, Crabb DP, Malik R, Garway-Heath DF. The relationship between variability and sensitivity in large-scale longitudinal visual field data. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(10):5985-5990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turpin A, McKendrick AM. What reduction in standard automated perimetry variability would improve the detection of visual field progression? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(6):3237-3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medeiros FA, Gracitelli CP, Boer ER, Weinreb RN, Zangwill LM, Rosen PN. Longitudinal changes in quality of life and rates of progressive visual field loss in glaucoma patients. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(2):293-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang F, Javitt JC, Tielsch JM. Racial variations in treatment for glaucoma and cataract among Medicare recipients. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1997;4(2):89-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostermann J, Sloan FA, Herndon L, Lee PP. Racial differences in glaucoma care: the longitudinal pattern of care. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(12):1693-1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diniz-Filho A, Delano-Wood L, Daga FB, Cronemberger S, Medeiros FA. Association between neurocognitive decline and visual field variability in glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(7):734-739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yaffe K, Fiocco AJ, Lindquist K, et al. ; Health ABC Study . Predictors of maintaining cognitive function in older adults: the Health ABC study. Neurology. 2009;72(23):2029-2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sachs-Ericsson N, Blazer DG. Racial differences in cognitive decline in a sample of community-dwelling older adults: the mediating role of education and literacy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(11):968-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masel MC, Peek MK. Ethnic differences in cognitive function over time. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(11):778-783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee HB, Richardson AK, Black BS, Shore AD, Kasper JD, Rabins PV. Race and cognitive decline among community-dwelling elders with mild cognitive impairment: findings from the Memory and Medical Care Study. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(3):372-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karlamangla AS, Miller-Martinez D, Aneshensel CS, Seeman TE, Wight RG, Chodosh J. Trajectories of cognitive function in late life in the United States: demographic and socioeconomic predictors. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(3):331-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atkinson HH, Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, et al. . Predictors of combined cognitive and physical decline. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1197-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alley D, Suthers K, Crimmins E. Education and cognitive decline in older Americans: results from the AHEAD sample. Res Aging. 2007;29(1):73-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medeiros FA, Zangwill LM, Girkin CA, Liebmann JM, Weinreb RN. Combining structural and functional measurements to improve estimates of rates of glaucomatous progression. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(6):1197-205.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medeiros FA, Leite MT, Zangwill LM, Weinreb RN. Combining structural and functional measurements to improve detection of glaucoma progression using Bayesian hierarchical models. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(8):5794-5803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenberg NA, Pritchard JK, Weber JL, et al. . Genetic structure of human populations. Science. 2002;298(5602):2381-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Girkin CA, Nievergelt CM, Kuo JZ, et al. ; ADAGES Study Group . Biogeographic ancestry in the African Descent and Glaucoma Evaluation Study (ADAGES): association with corneal and optic nerve structure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(3):2043-2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Results of Multivariable Regression Model Evaluating the Effect of Race on Visual Field Variability (SD of Residuals) Adjusting for Covariates and Socioeconomic Variables