Key Points

Question

What is the prognostic value of current staging systems for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) in nonselected patients?

Findings

In this nested case-control study drawn from a nation-wide cohort of 6721 patients with cSCC, 4 current staging systems distinguished poorly to moderately between patients who developed metastasis and those who did not. The ability to cluster patients with similar outcomes within the same staging category was low, particularly when using the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 7th edition, staging system; the systems used by Breuninger et al and Brigham and Women’s Hospital indicated increasing risk of metastasis by increasing stage or risk category.

Meaning

Four current staging systems for cSCC are unsatisfactory for clinical use in nonselected patients with cSCC.

Abstract

Importance

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) has metastatic potential, but the prognostic value of current staging systems in nonselected patients is uncertain.

Objective

To assess the effect of risk factors for metastasis and to evaluate validity and usefulness of 4 staging systems for cSCC using population-based data.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a nationwide, population-based, nested case-control study. The Cancer Registry of Norway, which receives compulsory data on all cancers in the Norwegian population of approximately 5.2 million inhabitants. All patients diagnosed as having a primary invasive cSCC in the period 2000 to 2004 (n = 6721) were identified. Of these, 112 patients were diagnosed with metastasis within 5 years. As control patients, 112 patients with cSCC without metastases, matched for sex and age at diagnosis, were identified by random. Clinical data and biopsy specimens of primary cSCC were collected for all 224 patients. The biopsies were reexamined histologically by an experienced pathologist using well-established criteria for cSCC, yielding 103 patients with metastasis (cases) and 81 cSCC without metastasis (controls).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The ability of 4 cSCC staging systems (ie, the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 7th edition [AJCC 7] staging system, the staging system used by Breuninger et al, the Brigham and Women’s Hospital [BWH] staging system, and the AJCC, 8th edition [AJCC 8] staging systems) to identify patients who developed metastasis with 5 years of follow-up. External validation was performed by logistic regression, discrimination (sensitivity, specificity, proportion correctly classified, concordance index), and calibration (R2, Hosmer-Lemeshow test, plots) statistics.

Results

Of 6721 patients; 3674 (54.7%) were men and 3047 (45.3%) were women, with a mean age at diagnosis of 78 years. Of the 103 patients with cSCC diagnosed with metastasis within 5 years, 60 [58.3%] were men, and mean [SD] age 72.7 [13.5] years. Of the 81 patients with cSCC without metastasis, 51 [63.0%] were men, and mean [SD] age 74.6 [11.7] 15 years. The staging systems distinguished poorly to moderately between patients who developed metastasis and those who did not. The ability to cluster patients with similar outcomes within the same staging category was low, particularly when using the AJCC 7 system. Using the AJCC 7 system, the risk of metastasis for T2 patients was 3-fold, compared with T1 patients (OR, 2.96; 95% CI, 1.43-6.15). In the system used by Breuninger et al, high-risk categories for diameter and tumor thickness and the BWH system’s T2b category collected relatively homogeneous groups. In the systems used by Breuninger et al and Brigham-Women’s Hospital, risk of metastasis was significantly elevated with increasing stage or risk category. Using the system by Breuninger et al, the risk of metastasis was less than 3-fold for tumors in the high-risk category of the combined variable (OR, 2.72; 95% CI, 1.29-5.74). The BWH system gave ORs for metastasis at 4.6 (95% CI, 2.23-9.49) and 21.31 (95% CI, 6.07-74.88) for the T2a and T2b categories, respectively.

Conclusions and Relevance

Using population-based data, 4 current staging systems for cSCC were unsatisfactory in identifying nonselected cSCC patients at high risk for metastasis. The system used by Breuninger gave the best results.

This nested case-control study assesses the validity and usefulness of 4 staging systems for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma using population-based data.

Introduction

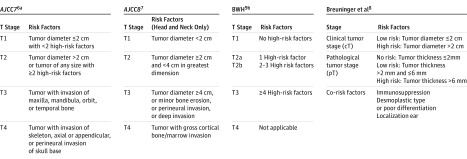

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is increasing in incidence and is now ranked as the second most common skin cancer world-wide. When excised surgically with free margins, the prognosis is mostly good, but it is poor if metastasis has occurred. Several staging systems for cSCC have been developed to predict patients’ risk of metastasis and to individualize treatment and the follow-up schedule (Figure 1). In 2011, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) published the 7th edition of its staging system (AJCC 7), which is based on tumor diameter and several risk features, including tumor depth, perineural invasion, primary site, and degree of differentiation as well as bone invasion. Although widely used, the AJCC 7 staging system has been criticized for low specificity and for being too complicated for use in clinical practice. Other staging systems have been introduced by Breuninger and coworkers (hereinafter, Breuninger system), primarily based on clinical tumor size and histological tumor thickness, and by a research group at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BHW), with 4 risk features defining the risk categories. Recently, an 8th edition of the AJCC staging system, to be used for cSCCs in the head-and-neck area only, has been introduced and will be implemented in 2018.

Figure 1. Overview of 4 Staging Systems for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma.

AJCC indicates American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual; BWH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

aHigh-risk factors: tumor thickness >2 mm, Clark level IV/V, poor or undifferentiated, perineural invasion, localization at ear or lip.

bHigh-risk factors: Tumor diameter ≥2 cm, invasion beyond subcutaneous fat, poorly differentiated, and perineural invasion.

These 4 staging systems for cSCC have been constructed using patients from large, tertiary referral centers, and none of them has been validated using population-based patient cohorts, making their validity in nonselected patients uncertain. In this study, we aimed to externally validate the 4 staging systems using population-based data from a high-quality national cancer registry. The results are reported according to the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement.

Methods

Since 1952, the Cancer Registry of Norway (CRN) has received compulsory information on all patients with cancer in Norway (population in 2015: approximately 5.2 million inhabitants). Information from several sources (eg, clinical records, pathology reports, and death certificates) ensures complete and high-quality data. We defined cSCC according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), code 44 (nonmelanoma skin cancer), and the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O-3) morphology codes: 80513 (verrucous carcinoma), 80523 (papillary squamous cell carcinoma), 80833 (basaloid squamous cell carcinoma) 80943 (basosquamous cell carcinoma), 80953 (metatypical carcinoma), and 80700 to 80769 (squamous cell carcinoma). We identified all patients registered in the CRN with a first, histologically verified, primary, and invasive cSCC from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2004 (6721 patients). Data on sex, age at diagnosis, date of diagnosis, anatomical site of the tumor, clinical stage, and histopathological variables were obtained from the CRN records. Kidney transplant recipients were identified by cross-linking the cohort with the national kidney transplantation registry, using the 11-digit personal identification number system implemented in Norway in 1964. Metastasis was coded according to local coding practice at the CRN, giving 2 categories: no metastases (ie, local disease only) and metastasis (ie, regional lymph nodes metastasis and/or distant metastasis). The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway (REG-REK 2012/21) and by the ethics review board at Oslo University Hospital.

Within 5 years of individual follow-up, 112 patients were diagnosed as having metastasis (eFigure and eReferences in Supplement). Among the 6609 patients without metastasis during follow-up, 112 patients, matched for sex and age at diagnosis, were selected at random. Tissue blocks from excision specimens of the tumors from these 224 patients were retrieved from 20 hospital laboratories throughout Norway. Histological slides from the original tissue blocks were cut, stained with hematoxylin-eosin, and reexamined by an experienced pathologist (O.P.F.C.), who was blinded regarding the metastatic status of the patient, using well-established diagnostic criteria for cSCC. When the diagnosis of cSCC could not be confirmed, the patient was excluded from further analyses, yielding a study sample of 103 patients with cSCC with metastasis (cases) and 81 patients without metastasis (controls). For both patient groups, information on immunosuppressive therapy (yes, no), anatomical site of the tumor (ear or lip, other), tumor diameter (in centimeters), tumor thickness (in millimeters), Clark level (I/II/II and IV/V), invasion beyond subcutaneous fat (yes, no), degree of differentiation (high to moderate and poor), perineural invasion (yes, no) and desmoplastic type (yes, no) were registered. Some variables were not assessable in all patients. Descriptive statistics are presented as means (SDs) and range for continuous variables and as frequencies with proportions for categorical variables.

Tumors were classified according to the AJCC 7, Breuninger, BWH and AJCC 8 staging systems. For each of the staging systems, comparisons of groups with and without metastasis were performed, using χ2 test. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to estimate the relative risk of metastasis by stage or risk category within each staging system. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs.

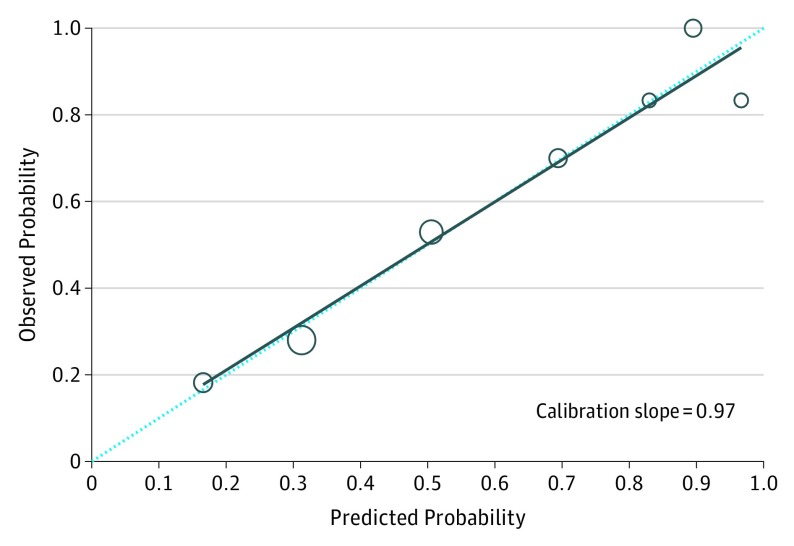

Evaluation of model performance was assessed in terms of calibration and discrimination. Calibration was related to goodness-of-fit, which reflects the agreement between observed outcomes and predictions. The calibration plot presents predicted probabilities (for groups) on the x-axis and the mean observed outcome on the y-axis. Perfect calibration should lie on a 45° line of the plot (ie, slope equals 1). The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test is calculated when the number of “risk groups” is so large that continuous approximation is feasible. P < .05 indicates a poor calibration of the model. The plot and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test was calculated for the Breuninger system. The AJCC 7, AJCC 8, and BWH systems consisted of only 1 variable (eg, T-stages). Thus, the underlying assumption performing the Hosmer-Lemeshow test is not fulfilled, and a presentation of calibration plot is not justifiable. Furthermore, as a measure of overall performance, we considered the explained variation (R2) by the model using the definition proposed by Nagelkerke.

Discrimination refers to the ability of a prediction model to differentiate between 2 outcome classes (ie, patients who developed metastasis and those who did not). Sensitivity, specificity, and proportion of cases correctly classified were used to evaluate classification performance. The concordance index (C-index), which is mathematically identical to area under the curve (AUC) for binary outcomes, is the most widely used measure to indicate discriminatory ability. The C-index can be interpreted as the probability that a patient with an outcome is given higher probability of the outcome by the model than a randomly chosen patient without the outcome. A value of 0.5 indicates that the model has no discriminatory ability, and a value of 1.0 indicates that the model has perfect discrimination ability. All data were analyzed using Stata statistical software (release 14; StataCorp LP).

Results

Mean age at diagnosis of cSCC was lower in patients with metastasis, particularly in those using immunosuppressive medication (Table 1). In patients with metastasis, primary tumor was more frequently located on ear and lip, had more often a diameter greater than 2 cm, tumor thickness greater than 6 mm, invasion beyond subcutaneous fat, and poor differentiation, and was more often of desmoplastic type, compared with tumors in patients without metastasis (Table 1). With 112 patients with cSCC developing metastasis within 5 years, the 5-year metastasis rate was 1.5%.

Table 1. Demographic and Tumor Characteristics in Patients With Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma With and Without Metastasis Within 5 Years of Individual Follow-upa.

| Characteristic | With Metastasis (n = 103) |

Without Metastasis (n = 81) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 72.7 (13.5) | 74.6 (11.7) |

| (Range) | (32-95) | (32-92) |

| Sex | ||

| Women | 43 (41.7) | 30 (37.0) |

| Men | 60 (58.3) | 51 (63.0) |

| Immunosuppression | ||

| No | 96 (93.2) | 79 (97.5) |

| Yes | 7 (6.8) | 2 (2.5) |

| Site | ||

| Ear | 21 (20.4) | 12 (14.8) |

| Lip | 18 (17.5) | 6 (7.4) |

| Other sites | 64 (62.1) | 63 (77.8) |

| Diameter | ||

| ≤2 cm | 55 (53.4) | 74 (91.4) |

| >2 cm | 40 (38.8) | 7 (8.6) |

| Nonassessable | 8 (7.8) | 0 |

| Histological thickness | ||

| <2 mm | 7 (6.8) | 24 (29.6) |

| 2-6 mm | 48 (46.6) | 50 (61.7) |

| >6 mm | 34 (33.0) | 6 (7.4) |

| Nonassessable | 14 (13.6) | 1 (1.2) |

| Clark level | ||

| I/II/III | 10 (9.7) | 25 (30.9) |

| IV/V | 74 (71.8) | 54 (66.7) |

| Nonassessable | 19 (18.5) | 2 (2.5) |

| Invasion beyond subcutaneous fat | ||

| No | 50 (48.5) | 74 (91.4) |

| Yes | 33 (32.0) | 6 (7.4) |

| Nonassessable | 20 (19.4) | 1 (1.2) |

| Differentiation | ||

| Highly/moderately | 65 (63.1) | 78 (96.3) |

| Poorly | 23 (22.3) | 2 (2.5) |

| Nonassessable | 15 (14.6) | 1 (1.2) |

| Perineural invasion | ||

| No | 82 (79.6) | 78 (96.3) |

| Yes | 5 (4.9) | 2 (2.5) |

| Nonassessable | 16 (15.5) | 1 (1.2) |

| Desmoplastic type | ||

| No | 71 (69.0) | 74 (91.4) |

| Yes | 16 (15.5) | 6 (7.4) |

| Nonassessable | 16 (15.5) | 1 (1.2) |

Data are given as number (percentage). Data on race/ethnicity were not available. Most patients (>95%) were white.

Staging

A large proportion of patients with (83 [85.6%]) and without (54 [66.7%]) metastasis fell into the T2 category of the AJCC 7 system, while none were in the T3 and T4 categories (Table 2). Using the Breuninger system, a higher proportion of patients with metastasis fell into the high-risk categories: tumor diameter, tumor thickness, and a combined variable of these and 1 or more of 4 high-risk features, compared with patients without metastasis (Table 2). Using the BWH system, most patients without metastasis fell into the T1 category, while patients with metastasis were almost equally distributed in the T1, T2a, and T2b categories (Table 2). When the patients were categorized according to the AJCC 8 system, about 10% of the patients with and without metastasis fell into the T2 category, while less than 20% of patients without metastasis and more than 50% of patients with metastasis fell into the T3 category (Table 2). No patients had tumors that fitted with the T4 category.

Table 2. Patients With Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma With and Without Metastasis Within 5 Years of Individual Follow-up, Staged According to 4 Staging Systems.

| Staging System | No. (%) | χ2 Test P Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| With Metastasis (n = 103) |

Without Metastasis (n = 81) |

||

| AJCC, Seventh Edition | .003 | ||

| T1 | 14 (14.4) | 27 (33.3) | |

| T2 | 83 (85.6) | 54 (66.7) | |

| T3 | 0 | 0 | |

| T4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown | 6 (5.8) | 0 | |

| Breuninger et al | <.001 | ||

| Diameter | |||

| Low-risk (≤2 cm) | 55 (53.4) | 74 (91.4) | |

| High-risk (>2 cm) | 40 (38.8) | 7 (8.6) | |

| Unspecified | 8 (7.8) | 0 | |

| Depth of invasion | |||

| No risk (<2 mm) | 7 (6.8) | 24 (29.6) | |

| Low-risk (2-6 mm) | 48 (46.6) | 50 (61.7) | |

| High-risk (>6 mm) | 34 (33.0) | 6 (7.4) | |

| Unspecified | 14 (13.6) | 1 (1.2) | |

| With additional factors | |||

| Low-risk | 49 (47.6) | 61 (75.3) | |

| High-risk | 54 (52.4) | 20 (24.7) | |

| BWH | <.001 | ||

| T1 | 32 (31.1) | 62 (76.5) | |

| T2a | 38 (36.9) | 16 (19.8) | |

| T2b | 33 (32.0) | 3 (3.7) | |

| T3 | 0 | 0 | |

| AJCC, Eighth Edition | <.001 | ||

| T1 | 26 (32.9) | 39 (69.6) | |

| T2 | 8 (10.1) | 6 (10.7) | |

| T3 | 45 (57.0) | 11 (19.7) | |

| T4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown | 5 (4.9) | 0 | |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual; BWH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Risk of Metastasis

Using the AJCC 7 system, the risk of metastasis for T2 patients was 3-fold, compared with T1 patients (OR, 2.96; 95% CI, 1.43-6.15). Using the Breuninger system, the risk of metastasis were 6-fold for tumor diameter greater than 2 cm (OR, 5.92; 95% CI, 2.18-16.07), 9-fold for tumors with depth of invasion greater than 6 mm (OR, 9.00; 95% CI, 3.51-32.31), but less than 3-fold for tumors in the high-risk category of the combined variable (OR, 2.72; 95% CI, 1.29-5.74). The BWH system gave ORs for metastasis at 4.6 (95% CI, 2.23-9.49) and 21.31 (95% CI, 6.07-74.88) for the T2a and T2b categories, respectively. Finally, the AJCC 8 system gave 2-fold (OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 0.62-6.44) and 6-fold (OR, 6.14; 95% CI, 0.41-1.09) risk of metastasis for the T2 and T3 categories, respectively, although this was not statistically different from the T1 category. Invasion beyond subcutaneous fat was the strongest predictor for metastasis when using AJCC 8.

External Validation

The AJCC 7 system had highest sensitivity, but lowest specificity, lowest proportion of correctly classified cases, and results regarding C-index and R2 test (Table 3). In contrast, AJCC 8 had lower sensitivity but much higher specificity and improvement in proportion of correctly classified tumors, C-index, and R2 compared with AJCC 7. The BWH system had the highest specificity and the second highest proportion of correctly classified tumors and C-index. The external validation demonstrated the best results for the Breuninger system, with high sensitivity (77.3%), specificity (75.0%), correctly classified tumors (76.2%), and C-index (0.81). The model was well calibrated, with a slope of 0.97 and Hosmer-Lemeshow test P = .11, the largest value of R2 (0.23) (Figure 2 and Table 3).

Table 3. External Validation of 4 Staging Systems for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Presented as Discrimination and Calibration Statistics.

| Staging System | No. | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Correctly Classified % | C Index | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AJCC, Seventh Edition | 178 | 85.6 | 33.3 | 61.8 | 0.59 | 0.04 |

| Breuninger et al | 168 | 77.3 | 75.0 | 76.2 | 0.81 | 0.23 |

| BWH | 184 | 68.9 | 76.5 | 72.3 | 0.75 | 0.18 |

| AJCC, Eighth Editiona | 135 | 67.1 | 69.6 | 68.2 | 0.70 | 0.12 |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual; BWH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Head and neck tumors only.

Sensitivity, specificity, correctly classified, concordance index (C index), and Nagelkerke R2.

Figure 2. Calibration Plot Based on Risk Features of the Breuninger et al Staging System.

Calibration plot of observed proportion against predicted probability of having metastasis in patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, based on risk features in the Breuninger et al staging system. The dotted diagonal lines represent the ideal line where the actual probability of metastasis matches the predicted probability. The larger circles indicate that these points are based on more data.

Discussion

The goal of any cancer staging system is to separate patients with cancer into groups that have significantly different prognosis and different need for treatment and follow-up. These groups should differ in terms of outcome (distinctiveness), have similar outcome within each group (homogeneity), and have worsening outcome with increasing stage (monotonousness). By estimating the relative contribution of risk factors for metastasis from cSCC in multivariate data analyses, we have estimated the validity and usefulness of 4 staging systems in nonselected patients with cSCC. To our knowledge, this is the first study to externally validate current staging systems for cSCC using population-based data.

The 4 staging systems distinguished poorly to moderately between patients who developed metastases and those who did not. The poorest results were found for the AJCC 7 system, which is most widely used. This is in line with results from hospital-based cohort studies. The Breuninger system’s high-risk categories and the BWH system’s T2b category collected relatively homogenous groups. The BWH system and, to a lesser degree, the Breuninger system gave significantly elevated risk of metastasis by increasing stage or risk category. Although the AJCC 7 system gave increased risk of metastasis for T2 patients compared with T1 patients, no patients were in the T3 and T4 categories. Similar findings have been reported in hospital-based cohort studies, making this staging system less useful. Similar objections have been put forward by other authors based on clinical experience.

The AJCC 7 system has also been criticized for being too complicated owing to the high number of combined variables. The Breuninger system is simpler, being based on clinical tumor size (with 2 categories) and histological tumor thickness (with 3 categories). The BWH staging system is also relatively straightforward, with only 4 variables, with the number of prognostic factors defining the risk categories. The AJCC 8 staging system is a major revision of the AJCC 7 system, including head and neck cSCCs only, and thereby limiting its usefulness.

Only 1.5% of the cSCCs metastasized within 5 years, which is a considerably lower rate than the metastatic rate found in studies from tertiary centers. Our cohort is population-based, which we believe is a major strength, and probably includes more patients with small or thin cSCC than hospital-based studies. A recently published population-based study, from the United Kingdom, reports a cSCC metastasis rate of 1.2% (ie, close to our finding). Our data were retrieved from a high-quality national cancer registry, yielding reliable data from nonselected patients. The CRN has been shown to be close to complete, and there are no indications that this is not valid for cSCC metastasis too. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out that metastasis in some patients with cSCC may have been missed, especially in very old patients.

By obtaining specimens from surgical excisions of primary cSCC in patients with and without metastasis, we were able to include all risk factors in the 4 staging systems. All specimens were reexamined by 1 experienced pathologist (O.P.F.C.), using well-established diagnostic criteria.

Limitations

A limitation of our study is that more controls than cases were excluded from the analyses after diagnostic reevaluation. However, the underlying assumption for performing the Hosmer-Lemeshow test for the AJCC 7, BWH, and AJCC 8 systems would still not be fulfilled with more controls. Moreover, most ORs in our logistic regression analyses were significant, making it unlikely that an increase in the number of controls would change the results in a meaningful way. An additional search for more patients without metastasis would have been ideal, but was not possible within limited time and resources. Other limitations were lack of information on local recurrences and that death was not included as an outcome. Moreover, some nonkidney organ transplant recipients may have been misclassified as immunocompetent, because data on nonkidney organ transplant recipients were not available.

A staging system for cSCC has to be suitable for use in everyday clinical practice. Risk factors should be easy to measure, and the measurements should be robust and reliable. The interobserver agreement should be high, as has been shown to be the case for pathologists’ measurements of tumor thickness and assessments of tumor differentiation. For clinicians, tumor diameter is easy to measure, although this is not always done, and clinical tumor diameter and histological tumor thickness are shown to correlate well. For many biopsy specimens, however, accurate assessment of tumor depth may not be possible because the tumor boundary extends beyond the base of the biopsy. Punch biopsies can therefore not be used to correctly identify key prognostic factors in cSCC, unless the biopsy is large and the tumor small. Using shaving and curettage techniques, the tissue architecture will not be preserved, and thus it might be difficult to measure the true tumor depth. Therefore, variables included in the 4 staging systems validated in this study may be difficult to assess accurately, which give them limited value for clinicians, as also pointed out by other authors.

Conclusions

The 4 current staging systems for cSCC performed unsatisfactory in identifying patients with cSCC at high risk for metastasis, in a nonselected material. The Breuninger system, primarily based on clinical tumor size and histological tumor thickness, gave the best results. Our findings indicate a need for a more reliable, easy-to-perform and clinical useful staging system than those presently available.

eTable. Odds ratios for metastasis

eReferences

References

- 1.Lomas A, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath-Hextall F. A systematic review of worldwide incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(5):1069-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(13):975-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brantsch KD, Meisner C, Schönfisch B, et al. . Analysis of risk factors determining prognosis of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(8):713-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mourouzis C, Boynton A, Grant J, et al. . Cutaneous head and neck SCCs and risk of nodal metastasis: UK experience. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2009;37(8):443-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brougham ND, Dennett ER, Cameron R, Tan ST. The incidence of metastasis from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and the impact of its risk factors. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106(7):811-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farasat S, Yu SS, Neel VA, et al. . A new American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: creation and rationale for inclusion of tumor (T) characteristics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(6):1051-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O’Sullivan B, et al. . Head and neck cancers: major changes in the American Joint Committee on cancer Eighth Edition Cancer Staging Manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):122-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breuninger H, Brantsch K, Eigentler T, Häfner HM. Comparison and evaluation of the current staging of cutaneous carcinomas. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10(8):579-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karia PS, Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Harrington DP, Murphy GF, Qureshi AA, Schmults CD. Evaluation of American Joint Committee on Cancer, International Union Against Cancer, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital tumor staging for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(4):327-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warner CL, Cockerell CJ. The new seventh edition American Joint Committee on Cancer staging of cutaneous non-melanoma skin cancer: a critical review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12(3):147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KG. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ. 2015;350:g7594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen IK, Småstuen M, Johannesen TB, et al. . Data quality at the Cancer Registry of Norway: an overview of comparability, completeness, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(7):1218-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonerandi JJ, Beauvillain C, Caquant L, et al. ; French Dermatology Recommendations Association (aRED) . Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 5):1-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagelkerke N. Miscellanea: a note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika. 1991;78(3):691-692. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu MB, Slutsky JB, Dhandha MM, et al. . Evaluation of the definitions of “high-risk” cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma using the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging criteria and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. J Skin Cancer. 2014;2014:154340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lansbury L, Bath-Hextall F, Perkins W, Stanton W, Leonardi-Bee J. Interventions for non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: systematic review and pooled analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2013;347:f6153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kauvar AN, Arpey CJ, Hruza G, Olbricht SM, Bennett R, Mahmoud BH. Consensus for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment, part II: squamous cell carcinoma, including a cost analysis of treatment methods. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(11):1214-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller SJ. Staging cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(4):472-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stratigos A, Garbe C, Lebbe C, et al. ; European Dermatology Forum (EDF); European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO); European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) . Diagnosis and treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(14):1989-2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breuninger H. Seventh edition American Joint Committee on Cancer staging of cutaneous non-melanoma skin cancer: viewpoint by Helmut Breuninger. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12(3):155-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Kanetsky PA, Karia PS, et al. . Evaluation of AJCC tumor staging for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and a proposed alternative tumor staging system. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(4):402-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(6):976-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinberg AS, Ogle CA, Shim EK. Metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: an update. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(8):885-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karia PS, Han J, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(6):957-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmults CD, Karia PS, Carter JB, Han J, Qureshi AA. Factors predictive of recurrence and death from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a 10-year, single-institution cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(5):541-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roozeboom MH, Lohman BG, Westers-Attema A, et al. . Clinical and histological prognostic factors for local recurrence and metastasis of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: analysis of a defined population. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93(4):417-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson TG, Ashton RE. Low incidence of metastasis and recurrence from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma found in a UK population: do we need to adjust our thinking on this rare but potentially fatal event? J Surg Oncol. 2017;116(6):783-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westers-Attema A, Joosten VM, Roozeboom MH, et al. . Correlation between histological findings on punch biopsy specimens and subsequent excision specimens in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(2):181-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buethe D, Warner C, Miedler J, Cockerell CJ. Focus issue on squamous cell carcinoma: practical concerns regarding the 7th Edition AJCC staging guidelines. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:156391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Odds ratios for metastasis

eReferences