Key Points

Question

What are the most common complications of facial implants, locations associated with complications, and factors raised in litigation related to facial implants?

Findings

Thirty-nine adverse events reported to the US Food and Drug Administration were included in this cross-sectional study, with infection the most common complication reported and 32 patients requiring removal of their implants. Half of malpractice cases involved allegedly inadequate informed consent.

Meaning

Prior to facial implant surgery, it is critical to have a thorough discussion of possible complications and techniques to treat them.

This cross-sectional study examines complications and litigation following facial implant surgery.

Abstract

Importance

Facial implants represent an important strategy for providing instant and long-lasting volume enhancement to address both aging and posttraumatic defects.

Objective

To better understand risks of facial implants by examining national resources encompassing adverse events and considerations facilitating associated litigation.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A cross-sectional study reviewed complications following facial implants. The procedures reviewed were performed on patients at locations throughout the United States from January 2006 to December 2016. Data collection was completed in March 2017.

The Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience database, which contains medical device reports submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), was searched for complications that occurred from January 2006 to December 2016 involving facial implants made by Implantech, MEDPOR, Stryker, KLS Martin, and Synthes. Furthermore, the Thomson Reuters Westlaw legal database was searched for relevant litigation.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The complications of facial implants were analyzed in relation to the location of implant and severity of complication. Litigation was analyzed to determine which factors determine outcome.

Results

Thirty-nine instances of adverse events reported to the FDA were identified. Sixteen (41%) involved malar implants, followed by 12 chin implants (31%). The most common complications included infection (18 [46%]), implant migration (9 [23%]), swelling (7 [18%]), and extrusion (4 [10%]). Thirty-two patients (83%) had to have their implants removed. Infection occurred at a mean (SD) of 83.3 (68.8) days following the surgery. One-third of complications involved either migration or extrusion. The mean (range) time to migration or extrusion was 381.1 (10-2400) days. In 12 malpractice cases identified in publicly available court proceedings, alleged inadequate informed consent and requiring additional surgical intervention (ie, removal) were the most commonly cited factors.

Conclusions and Relevance

Infection and implant migration or extrusion are the most common complications of facial implants. Most of these complications necessitate removal. These considerations need to be discussed with patients preoperatively as part of the informed consent process, as allegedly inadequate informed consent was cited in a significant proportion of resultant litigation, and there were overlapping considerations among adverse events reported to the FDA and factors brought up in relevant litigation. Cases resolved with settlements and jury-awarded damages encompassed considerable award totals.

Level of Evidence

NA.

Introduction

Facial implants represent an attractive strategy for addressing the aging face and rehabilitating prior injury.1 Commonly used in conjunction with other procedures, facial implants promote increased definition in the mental and malar regions, leading to a youthful appearance and enhancing the nose-chin relationship.2,3 Although these procedures are generally considered safe, the true incidence of complications may be difficult to ascertain. To our knowledge, there have been no large-scale analyses of related adverse events. Improving our understanding of associated complications may improve preoperative counseling and avoid complications.

To better characterize adverse events related to facial implants, we examined a national resource for reported complications as well as specific factors raised in malpractice litigation. Prior studies4,5,6 analyzing malpractice litigation involving facial plastic surgery procedures have demonstrated that a perceived lack of informed consent is among the most commonly cited factors. Hence, comprehensive preoperative discussions with patients might help decrease the incidence of malpractice litigation.7 Our objective with this project was to enhance the information available to physicians surrounding adverse events of facial implants, facilitating a comprehensive preoperative patient-physician discussion with the hope of ultimately improving patient satisfaction and minimizing malpractice litigation.

Methods

This study used publicly available data that did not contain patient identifying information; therefore, internal review board approval and patient consent were not required. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database was used to identify reportable events over the most recent decade of information available (January 2006 to December 2016). The FDA mandates adverse event reporting, and manufacturers have 10 days to submit cases after being informed of these events. Each report is a master record that contains information relating to the outcome of the event and any associated interventions. Injuries from facial implants provided by the following companies were available through this resource: Implantech, MEDPOR, Stryker, KLS Martin, and Synthes. This resource has shown its unique value in numerous other analyses examining injury-related events.8,9,10,11,12 The location of implantation, specific complication(s) reported, time to complication, and other clinical issues available were included in this analysis.

The Thomson Reuters Westlaw database was accessed and searched for litigation progressing to inclusion in publicly available federal and state court records. This resource is subscription based and among the databases most widely used by legal professionals. It has been examined for medicolegal analyses relating to numerous other issues relevant to physicians performing facial aesthetic procedures.4,5,6,13,14,15,16 Verdict and settlement reports were obtained using the advanced search function with the following search terms: “medical malpractice” AND “chin implant” OR “facial implant” OR “malar implant” OR “submalar implant” OR “cheek implant” OR “nasal implant” OR “nose implant” OR “malar” OR “submalar” OR “tear trough” OR “mandible augmentation” OR “mandible implant” OR “jaw augmentation” OR “jaw implant” OR “cheek augmentation” OR “cheek implant” OR “chin augmentation” OR “face implant” OR “midfacial augmentation” OR “midface augmentation” OR “midface implant.” Each individual jury verdict and settlement report was evaluated for outcome, award, defendant specialty, location of implant, other clinical characteristics, and factors facilitating the decision to pursue malpractice litigation.

As data were not normally distributed, Mann-Whitney U tests and the Fisher exact test were used for comparison of continuous and categorical variables, respectively. To account for multiple comparisons on the same data set, the Dunn-Sidak correction was used. P values were considered statistically significant if they were below the corrected threshold of .007. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS version 20 (IBM). Data collection was completed in March 2017.

Results

Reportable Adverse Events

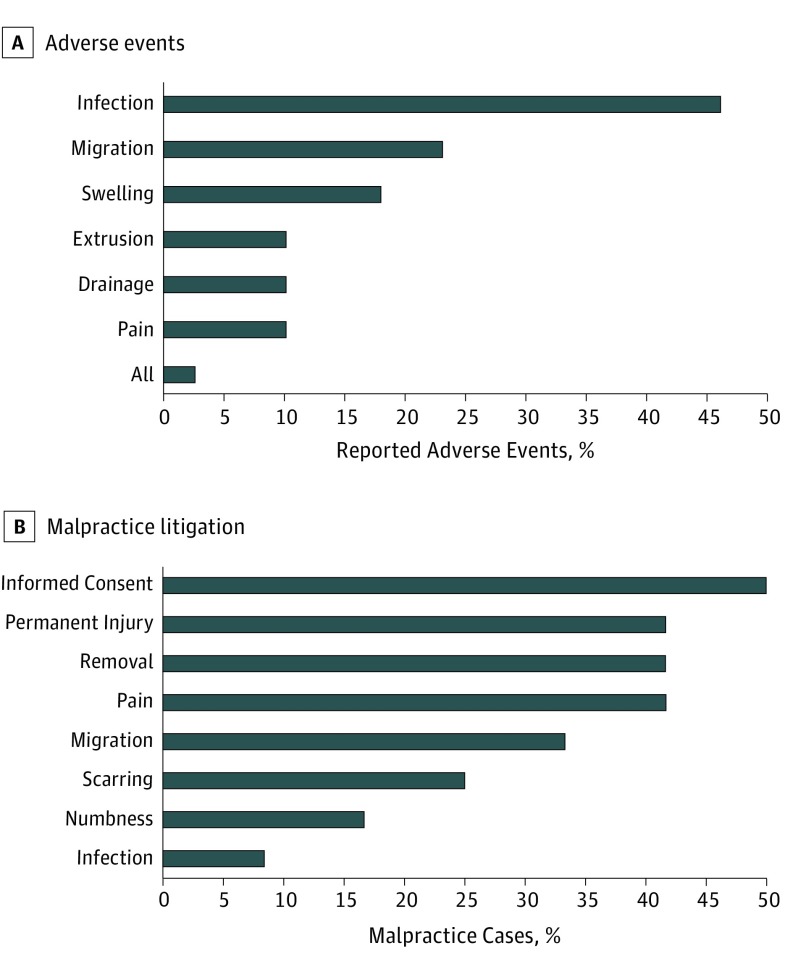

Thirty-nine instances of adverse events relating to the use of facial implants were identified in the MAUDE database. Sixteen (41%) involved implants in the malar region, followed by injuries from chin implants (12 [31%]) and submalar implants (4 [10%]). Nearly half of all adverse events reported involved infection (18 [46%]), followed in frequency by migration (9 [23%]), swelling (7 [18%]), and extrusion (4 [10%]). Other complications reported are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Complications Among Cases Reported to the US Food and Drug Administration and Allegations Raised in Relevant Litigation.

A, Infection was the most commonly reported adverse event, followed by migration, swelling, and extrusion. B, Allegedly inadequate informed consent was the issue most commonly cited in malpractice litigation. Permanent injury, removal of the implant, and pain were also commonly cited.

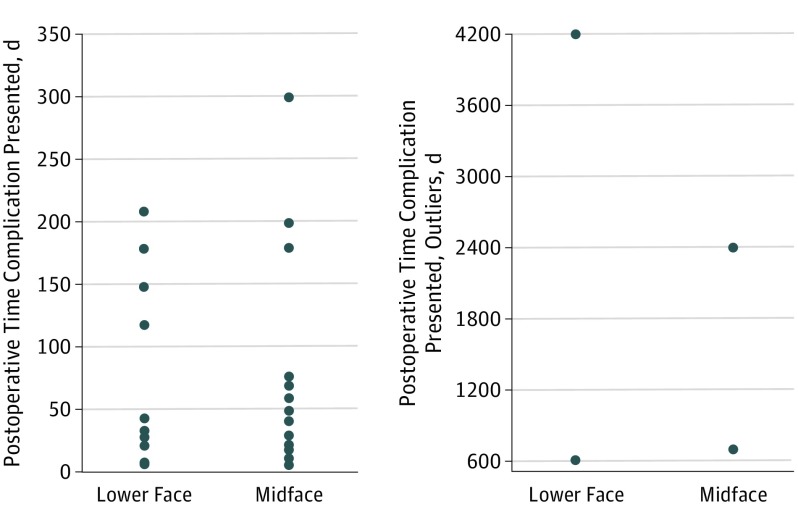

Reported events occurred during a wide range of times following implant placement. For lower face implants (ie, mandible and chin implants), these complications were reported at a median (range) of 45 (8-2400) days postoperatively compared with 45.5 (6-2400) days for midface implants (Mann-Whitney U test, P = .88) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Timing of Adverse Events Among Complications Reported to the US Food and Drug Administration.

Reported events occurred during a wide range of times following implant placement. For lower face implants (ie, mandible and chin implants), these complications were reported at a median (range) of 45 (8-2400) days postoperatively compared with 45.5 (6-2400) days for midface implants.

Trends in adverse events organized by general facial location (lower face for chin/mandible implant vs midface for others) are illustrated in Table 1. Notably, although a greater proportion of lower face complications involved pain (3 [20%]), migration (4 [27%]), and infection (4 [27%]) compared with adverse events reported for midface implants (1 [4%], 5 [21%], and 5 [21%], respectively), these comparisons did not reach statistical significance (P > .007 for all).

Table 1. Complications by Anatomical Location.

| Location, No. | Total, No. | No. (%) | Postoperative Time Complication Presented, d | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | Swelling | Extrusion | Migration | Drainage | Infection | Permanent Injury | Removal | |||

| Midface | 24 | 1 (4) | 5 (21) | 3 (13) | 5 (21) | 3 (13) | 5 (21) | 3 (13) | 10 (42) | 45.5 |

| Malar | 16 | 0 | 3 (19) | 1 (6) | 3 (19) | 2 (13) | 12 (75) | 3 (19) | 6 (38) | 55 |

| Nasal | 3 | 0 | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (100) | 300 |

| Submalar | 4 | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (25) | 35.5 |

| Tear trough | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| Lower face | 15 | 3 (20) | 2 (13) | 1 (7) | 4 (27) | 1 (7) | 4 (27) | 1 (7) | 7 (47) | 40 |

| Chin | 12 | 3 (25) | 2 (17) | 1 (8) | 2 (17) | 1 (8) | 4 (33) | 1 (8) | 5 (42) | 35 |

| Mandible | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (67) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (67) | 150 |

Malpractice Litigation

Of 18 initial jury verdict and settlement and reports obtained, 6 were excluded (1 duplicate and 5 nonrelevant). Of 12 cases analyzed, 9 (75%) related to chin implants, 2 (17%) involved nasal implants, and 1 (8%) involved a mandible implant. The most commonly cited defendants were plastic surgeons (8 cases [67%]), otolaryngologists (2 cases [17%]), anesthesiologists (2 cases [17%]), an oral surgeon (1 case [8%]), and a chiropractor (1 case [8%]). With regard to the cases involving an anesthesiologist, in 1 case the otolaryngologist (a facial plastic surgeon) and anesthesiologist were accused of “abandoning” the patient postoperatively; the patient was found in cardiac arrest by a nurse. In the other case, a chin implant was performed in conjunction with tonsillectomy and septoplasty, and during this procedure faulty endotracheal tube placement was not recognized and the patient sustained hypoxic brain injury. The other 10 malpractice cases involved intraoperative or postoperative sequelae directly related to the facial implants used.

Nine cases (75%) were resolved in the defendant’s favor, while the other cases were resolved with jury-awarded damages to the plaintiff (Table 2). Common allegations included inadequate informed consent (6 cases [50%]), permanent injury (5 cases [42%]), requiring implant removal (5 cases [42%]), and pain (5 cases [42%]). Other allegations raised are illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 2. Individual Jury Verdict Reports for Facial Implant Malpractice Litigationa.

| Patient No. | Location | Verdict in Favor of (Awards, US $) | Defendant | Inadequate Informed Consent | Death | Permanent Injury | Paresthesias | Time When Complication Occurred | Migration/ Removal Required |

Scarring or Poor Cosmesis | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chin | Defendant | Plastic surgeon | Yes | No | No | No | NA | Yes/Yes | No | Incorrectly sized |

| 2 | Chin | Defendant | Plastic surgeon | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Immediately postoperatively | No/No | No | Mental nerve injury |

| 3 | Mandible | Plaintiff (15 000) | Oral surgeon | No | No | Yes | No | 20 y | No | No | Teflon, resorption |

| 4 | Chin | Defendant | Plastic surgeon | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Immediately postoperatively | No/No | No | NA |

| 5 | Nasal | Plaintiff (237 000) | Plastic surgeon | No | No | Yes | No | 2 y | No/Yes | Yes | Retained after attempted removal |

| 6 | Chin | Plaintiff (100 000) | Plastic surgeon | No | No | No | No | 23 y | No/Yes | Yes | Dacron, foreign body reaction |

| 7 | Nasal | Defendant | Plastic surgeon | Yes | No | No | No | 6 wk | Yes/Yes | No | NA |

| 8 | Chin | Defendant | Plastic surgeon | No | No | No | No | NA | Yes/No | No | “Asymmetric” chin |

| 9 | Chin | Defendant | Chiropractor | Yes | No | No | No | NA | Yes/No | Yes | Displaced implant with jaw manipulation |

| 10 | Chin | Defendant | Plastic surgeon/ anesthesiologist |

No | Yes | No | No | Immediately postoperatively | No/No | No | Postoperative cardiac arrest |

| 11 | Chin | Defendant | Plastic surgeon | Yes | No | No | No | NA | No/No | No | Denied consenting |

| 12 | NA | Defendant | Otolaryngologist/ anesthesiologist |

No | No | Yes | No | Immediately postoperatively | No/No | No | Dislodged endotracheal tube, anoxic brain injury |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

Please note that all of these are allegations brought up in relevant cases.

Discussion

Facial implants can provide immediate and permanent augmentation of the face,1 and improvements in their design have further enhanced their use. Common sites of use include cheek implantation for malar hypoplasia, mentum augmentation, mandible implantation to provide more definition and improve the angle of the mandible, and dorsal nasal augmentation. In addition, computer-assisted custom-designed implants can be used to augment congenital and traumatic deformities.17 Despite the use of these implants, there have been no large-scale studies analyzing complications, to our knowledge. Having a thorough knowledge of potential complications is critical to the informed consent process, and deficiencies in preoperative patient counseling are often cited in associated malpractice litigation.5,6

A comparison between FDA-reported complications and factors cited in malpractice litigation demonstrated multiple areas of overlap. Of the cases reported to MAUDE, 9 (23%) cited implant migration as a complication, and in 8 of these cases (91%) the implant had to be removed. Five of the malpractice cases reviewed (42%) required implant removal, and of these cases 4 (33%) involved implant migration. One case involved migration of the implant into the maxillary sinus, detected by computed tomography. Implant migration and extrusion are often secondary to deficient surgical planning; adequate surgical dissection in the subperiosteal plane to create appropriate pocket sizes for the implant minimizes the risk of this.18 Pain was cited as a factor in 5 malpractice cases (42%) related to facial implants and was a complication in 4 cases (10.3%) reported to the FDA, including 3 cases (20%) specifically involving the lower face (Table 1). Pain was much more commonly cited in malpractice cases. Pain is subjective and difficult to quantify, and different patients have different thresholds. It is a commonly cited factor in malpractice litigation that can influence outcome.19

Infection was the most commonly reported complication (18 cases [46%]), and in 15 cases (83%) necessitated removal of the implant. However infection was reported as a factor in only 1 malpractice case (8%). Infection is seldom attributed to the implant material itself and most commonly results from poor surgical technique. The use of preoperative and postoperative antibiotics, aseptic technique, soaking the implant in antibiotic-impregnated solution, irrigating with antibiotic solution, and meticulous closure should greatly minimize the incidence of infection.20 Therefore, one would expect infection to be more often cited in malpractice litigation. Possible reasons for the low incidence of infection in malpractice litigation include generally adequate preoperative counseling about the risks of the surgery and the possible need for implant removal. Swelling was present in 5 midface complications (20.8%) compared with 2 lower face complications (13.3%). Midface implants are more commonly associated with swelling because of the increased soft-tissue dissection and the increased potential for seroma and hematoma compared with implants of the lower face.20 There are adverse events that appear commonly in litigation, including implant migration and procedures requiring implant removal. It is crucial that these possible complications are thoroughly discussed with patients preoperatively as part of comprehensive informed consent, as this may decrease the incidence of litigation.

Analysis of patient education materials demonstrated that a large portion of these websites fail to even mention complications of the surgery. With deficient informed consent being cited as a factor for litigation in a large number of malpractice cases, improving information available to patients may be a critical first step in remedying this problem.

There was no significance in timing of complication based on location. Most complications occurred within the first 60 days of surgery, with a median (range) of 47.5 (6-4200) days. The median (range) time for infection was 60 (8-210) days postoperatively. Close monitoring of patients is critical during this period to avoid missing a potential complication. Analysis of malpractice cases demonstrated that factors facilitating litigation were occurring 20 years following the initial surgery. These cases were related to foreign body reactions to implant materials such as Teflon, which is no longer used. Despite this, it is critical to maintain close follow-up of the patient for the first year to promptly diagnose any adverse consequences and appropriately manage them.

Limitations

The MAUDE database is a surveillance database, and underreporting may be inherent to its design. In addition, some records may be incomplete. Furthermore, there is no information on the frequency of facial implantation in the United States overall, so no conclusions can be made regarding prevalence and incidence of complications. Despite these limitations, this database is useful for analyzing common factors cited in reports of adverse events and their ultimate outcome. The Thomson Reuters Westlaw database used to analyze litigation has shown its value in myriad prior analyses but is not without limitations. The types of cases progressing to inclusion in public records differ by jurisdiction, so the database is useful for an analysis of factors raised in litigation (eg, this analysis) rather than for an estimate of the incidence of malpractice litigation in society as a whole. Hence, there are likely many proceedings, such as out-of-court settlements, that do not progress to the point of inclusion into public records.

Conclusions

Facial implants are a critical part of the facial plastic surgeon’s repertoire and can be used to treat patients who have undergone trauma or have congenital deformities or to enhance aesthetics. The most common adverse event reported is infection, and 32 reported adverse events (83.3%) involved patients having their implants surgically removed. The most common alleged factors raised in litigation related to facial implants included inadequate informed consent, permanent disfigurement, and implant removal. This does not strictly follow the incidence of reported complications, in which infection was most common. As many reported adverse events are also commonly noted in malpractice litigation, it is important for physicians to have a thorough discussion with patients preoperatively about potential complications, particularly the ones cited in this analysis. As an increasing number of patients learn about procedures from the internet, enhancing online patient education materials can help improve patients’ understanding of potential complications and facilitate the informed consent process.

References

- 1.Constantinides MS, Galli SK, Miller PJ, Adamson PA. Malar, submalar, and midfacial implants. Facial Plast Surg. 2000;16(1):35-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metzinger SE, McCollough EG, Campbell JP, Rousso DE. Malar augmentation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125(9):980-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prendergast M, Schoenrock LD. Malar augmentation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;115(8):964-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svider PF, Blake DM, Husain Q, et al. In the eyes of the law. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30(2):119-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svider PF, Eloy JA, Folbe AJ, Carron MA, Zuliani GF, Shkoukani MA. Craniofacial surgery and adverse outcomes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;124(7):515-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svider PF, Keeley BR, Zumba O, Mauro AC, Setzen M, Eloy JA. From the operating room to the courtroom. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(8):1849-1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herruer JM, Prins JB, van Heerbeek N, Verhage-Damen GW, Ingels KJ. Negative predictors for satisfaction in patients seeking facial cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(6):1596-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alemzadeh H, Raman J, Leveson N, Kalbarczyk Z, Iyer RK. Adverse events in robotic surgery. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0151470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connor MJ, Marshall DC, Moiseenko V, et al. Adverse events involving radiation oncology medical devices. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97(1):18-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez J, Soni A, Calva D, Susarla SM, Jallo GI, Redett R. Iatrogenic surgical microscope skin burns. Burns. 2016;42(4):e74-e80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raz Y. The utility of the MAUDE database in researching cochlear implantation complications. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131(3):251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tambyraja RR, Gutman MA, Megerian CA. Cochlear implant complications. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131(3):245-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blake DM, Svider PF, Carniol ET, Mauro AC, Eloy JA, Jyung RW. Malpractice in otology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(4):554-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farida JP, Lawrence LA, Svider PF, et al. Protecting the airway and the physician. Head Neck. 2016;38(5):751-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovalerchik O, Mady LJ, Svider PF, et al. Physician accountability in iatrogenic cerebrospinal fluid leak litigation. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(9):722-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rayess HM, Gupta A, Svider PF, et al. A critical analysis of melanoma malpractice litigation. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(1):134-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binder WJ, Kaye A. Reconstruction of posttraumatic and congenital facial deformities with three-dimensional computer-assisted custom-designed implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94(6):775-785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel K, Brandstetter K. Solid implants in facial plastic surgery. Facial Plast Surg. 2016;32(5):520-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor CL, Ranum D. Patient safety in neurosurgical practice. World Neurosurg. 2016;93:159-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkinson TS. Complications in aesthetic malar augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;71(5):643-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]