Abstract

This education intervention study reports on voluntary, patient-centered opioid tapering in outpatients with chronic pain without behavioral treatment.

The risks associated with prescription opioids are well described.1,2 Although reducing opioid use is a national priority, existing opioid tapering models use costly interdisciplinary teams that are largely inaccessible to patients and their physicians.3,4 Patients and physicians need solutions to successfully reduce long-term prescription opioid dosages in settings without behavioral services. We conducted a study of voluntary, patient-centered opioid tapering in outpatients with chronic pain without behavioral treatment.

Methods

Patients with non–cancer-related chronic pain prescribed long-term opioids at a community pain clinic were provided education about the benefits of opioid reduction (reduced health risks without increased pain) by their prescribing physician. Physicians offered to partner with patients to slowly reduce their opioid dosages over 4 months. The only exclusion was current treatment for substance use disorder. The study was approved by the Stanford University institutional review board; participants provided written or electronic informed consent, and no compensation was provided to participants.

Of the 110 eligible patients, 82 (75%) agreed to taper their opioid dosages; of those, 68 provided baseline demographics, information on opioid use, pain, marijuana use and psychosocial measures. Patients received a self-help book on reducing opioid use, and a slow, individually designed taper. Opioid dosages were reduced up to 5% for up to 2 dose reductions in month 1 to minimize negative physical and emotional response, withdrawal symptoms, and to facilitate patient confidence in the process. In months 2 to 4, patients were asked to further reduce use by as much as 10% per week; dose decrements were tailored to the patient. Patient responses were monitored with close clinical follow-up (at least monthly) and doses adjusted accordingly. Follow-up surveys were administered at 4 months; patients who provided data at 4 months were considered study completers. We confirmed patient-reported opioid prescription with medical record review. We documented patient compliance and accuracy of reported medication use with periodic urine drug testing and continuous monitoring of the state Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP). No compliance issues or aberrant prescriptions were noted. We converted opioid doses to morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD). Change in MEDD from baseline was the primary outcome and pain intensity was a secondary outcome. Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test was used for continuous variables and χ2 test for polychotomous variables.

Results

The patients’ mean (SD) age was 51 (12) years, and 41 (60%) were female. Thirty-one of 82 enrolled patients (38%) did not complete a 4-month follow-up survey and therefore were considered to have dropped out of the study. Depression negatively correlated (P = .05) and baseline marijuana use positively correlated (P = .04) with study completion. The Table provides characteristics and results for the sample; we found no sex association with study completion or opioid reduction.

Table. Characteristics and Outcomesa .

| Variable | Completers (n = 51) | Dropoutsb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 4 mo | P Valuec | Baseline | P Valued | ||||

| Median (IQR) | NA | Median (IQR) | NA | Median (IQR) | NA | |||

| Age | 52 (43-50) | 1 | 57 (50-63) | 0 | .12 | |||

| Opioid duratione | 6 (3-11) | 10 | 6 (5-8) | 4 | .57 | |||

| Opioid dosef | 288 (153-587) | 0 | 150 (54-248) | 0 | .002 | 244 (147-311) | 1 | .45 |

| Pain intensity | 5.0 (3.0-7.0) | 0 | 4.5 (3.0-7.0) | 3 | .29 | 3.5 (3.0-6) | 1 | .10 |

| PCS | 22 (10-30) | 1 | 15 (7-23) | 5 | .04 | 22 (20-30) | 0 | .39 |

| Fatigueg | 60 (54-65) | 4 | 59 (51-65) | 3 | .64 | 63 (59-66) | 2 | .45 |

| Anxietyg | 60 (53-64) | 1 | 54 (46-62) | 3 | .06 | 62 (59-63) | 1 | .35 |

| Depressiong | 56 (49-64) | 1 | 55 (48-61) | 2 | .31 | 62 (57-65) | 1 | .05 |

| Sleep disturbanceg | 59 (54-70) | 2 | 56 (50-64) | 2 | .13 | 62 (53-67) | 1 | .66 |

| Pain interferenceg | 63 (58-67) | 1 | 63 (57-67) | 2 | .44 | 66 (61-68) | 1 | .13 |

| Pain behaviorg | 60 (57-63) | 2 | 59 (56-64) | 2 | .47 | 62 (60-64) | 1 | .14 |

| Physical functiong,h | 39 (34-41) | 1 | 39 (34-43) | 2 | .78 | 36 (34-41) | 1 | .07 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; PCS, Pain Catastrophizing Scale.

Completers provided 4-month data, dropouts enrolled but did not provide month 4 data.

Thirty-one enrolled; 17 provided the baseline data.

Probability of difference between week baseline and 4 months for completers where null hypothesis is true.

Probability of baseline difference between completers and dropouts where null hypothesis is true.

Opioid duration (years taking opioids).

Opioid dose (morphine equivalent daily dose).

Patient Reported Outcomes Information System (PROMIS) measure.

Lower scores reflect worse function, pain (numeric rating scale).

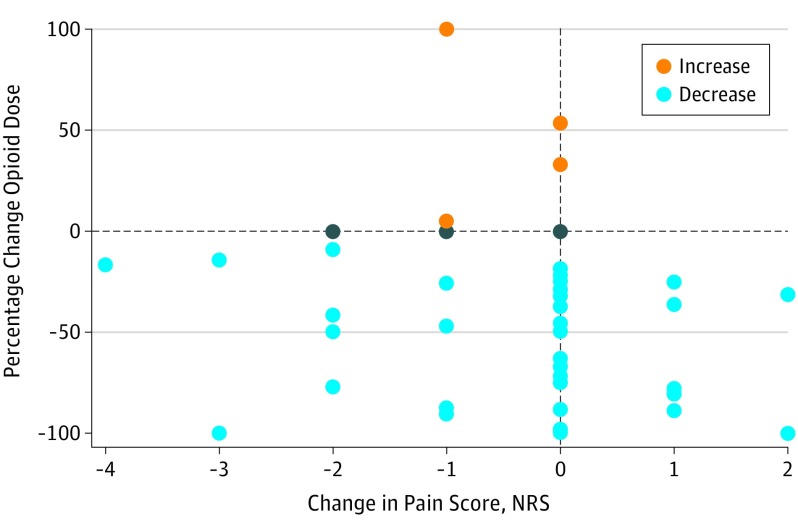

Among study completers (n = 51) baseline median MEDD (interquartile range [IQR]) was 288 (153-587) mg, with a median 6-year duration (IQR, 3-9) duration of opioid use. Median pain intensity was moderate (5 out of 10 on a numeric pain rating). After 4 months, the median MEDD was reduced to 150 (IQR, 54-248) mg (P = .002). The likelihood of a greater than 50% opioid dose reduction was not predicted by starting dose, baseline pain intensity, years prescribed opioids, or any psychosocial variable. Neither pain intensity (P = .29) nor pain interference (P = .44) increased with opioid reduction. The Figure shows the relationship between percentage change in MEDD and pain intensity in study completers.

Figure. Change in Opioid Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose and Absolute Change in Pain Intensity Score From Baseline to Month 4 for Study Completers.

NRS indicates numeric rating scale.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that a substantial fraction of patients at a pain clinic may wish to engage in voluntary opioid tapering. Our data challenge common notions that patients taking high-dose opioids will fail outpatient opioid tapers or that duration of opioid use predicts taper success. Combining patient education about the benefits of opioid reduction with a plan that reduces opioids more slowly than current tapering algorithms5 with close clinician follow-up may help patients engage and succeed in voluntary outpatient tapering. Because our data are generated from a single pain clinic, studies are needed to assess how well our protocol would generalize to other types of patients and settings.

References

- 1.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Russo JE, DeVries A, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. The role of opioid prescription in incident opioid abuse and dependence among individuals with chronic noncancer pain: the role of opioid prescription. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):557-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darnall BD, Stacey BR, Chou R. Medical and psychological risks and consequences of long-term opioid therapy in women. Pain Med. 2012;13(9):1181-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy JL, Clark ME, Banou E. Opioid cessation and multidimensional outcomes after interdisciplinary chronic pain treatment. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(2):109-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sullivan MD, Turner JA, DiLodovico C, D’Appollonio A, Stephens K, Chan YF. Prescription opioid taper support for outpatients with chronic pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain. 2017;18(3):308-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berna C, Kulich RJ, Rathmell JP. Tapering long-term opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain: evidence and recommendations for everyday practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(6):828-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]