Key Points

Question

What are biopsy rates and yield in the 90 days following screening among women with and without a personal history of breast cancer (PHBC)?

Findings

In this population-based cohort including 812 164 women undergoing screening (mammography vs magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] with or without mammography), there were 2-fold higher and 5-fold higher core and surgical biopsy rates following MRI compared with mammography among women with and without a PHBC, respectively, resulting in lower invasive cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ yield for both groups.

Meaning

Women with and without PHBC who undergo screening MRI experience higher biopsy rates coupled with significantly lower cancer yield compared with mammography alone.

This population-based cohort study uses cancer registry data to examine the biopsy rates and yield in the 90 days following screening (mammography vs MRI with or without mammography) among women with and without a personal history of breast cancer.

Abstract

Importance

There is little evidence on population-based harms and benefits of screening breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in women with and without a personal history of breast cancer (PHBC).

Objective

To evaluate biopsy rates and yield in the 90 days following screening (mammography vs magnetic resonance imaging with or without mammography) among women with and without a PHBC.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Observational cohort study of 6 Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) registries. Population-based sample of 812 164 women undergoing screening, 2003 through 2013.

Exposures

A total of 2 048 994 digital mammography and/or breast MRI screening episodes (mammogram alone vs MRI with or without screening mammogram within 30 days).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Biopsy intensity (surgical greater than core greater than fine-needle aspiration) and yield (invasive cancer greater than ductal carcinoma in situ greater than high-risk benign greater than benign) within 90 days of a screening episode. We computed age-adjusted rates of biopsy intensity (per 1000 screening episodes) and biopsy yield (per 1000 screening episodes with biopsies). Outcomes were stratified by PHBC and by BCSC 5-year breast cancer risk among women without PHBC.

Results

We included 101 103 and 1 939 455 mammogram screening episodes in women with and without PHBC, respectively; MRI screening episodes included 3763 with PHBC and 4673 without PHBC. Age-adjusted core and surgical biopsy rates (per 1000 episodes) doubled (57.1; 95% CI, 50.3-65.1) following MRI compared with mammography (23.6; 95% CI, 22.4-24.8) in women with PHBC. Differences (per 1000 episodes) were even larger in women without PHBC: 84.7 (95% CI, 75.9-94.9) following MRI and 14.9 (95% CI, 14.7-15.0) following mammography episodes. Ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive biopsy yield (per 1000 episodes) was significantly higher following mammography compared with MRI episodes in women with PHBC (mammography, 404.6; 95% CI, 381.2-428.8; MRI, 267.6; 95% CI, 208.0-337.8) and nonsignificantly higher, but in the same direction, in women without PHBC (mammography, 279.3; 95% CI, 274.2-284.4; MRI, 214.6; 95% CI, 158.7-280.8). High-risk benign lesions were more commonly identified following MRI regardless of PHBC. Higher biopsy rates and lower cancer yield following MRI were not explained by increasing age or higher 5-year breast cancer risk.

Conclusions and Relevance

Women with and without PHBC who undergo screening MRI experience higher biopsy rates coupled with significantly lower cancer yield findings following biopsy compared with screening mammography alone. Further work is needed to identify women who will benefit from screening MRI to ensure an acceptable benefit-to-harm ratio.

Introduction

Although mammography is the only test with evidence demonstrating breast cancer mortality reduction, its utility is challenged by false-positive recalls leading to additional imaging and invasive benign biopsies, interval invasive cancers, and overdiagnosis. Balancing the benefit-to-harm ratio of screening strategies has generated substantial debate, particularly over what constitutes a harm for whom, and what weight harms should be given relative to the benefit of a potential life saved.

Screening breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended to augment screening mammography for women at high breast cancer risk (eg, >20% lifetime risk); use among average- or low-risk women is not recommended. Screening breast MRI has increased in community practice, but its use still remains low even among the more than 2.8 million US women with a personal history of breast cancer (PHBC). Current guidelines recommend annual mammography for all women with treated breast cancer and recommend against routine MRI screening except for women who meet high-risk criteria for increased breast cancer surveillance. Screening mammography in women with a PHBC has limitations, with approximately 35% of second breast cancers presenting as interval cancers within 1 year of a negative result on a surveillance mammogram, with 5-year risk of interval invasive second breast cancer varying widely across women. This presents a clear opportunity to improve clinical care women with a PHBC. New imaging technologies offer promise for screening, but biopsy rates and yield have not been well established, particularly in community settings.

We previously reported findings from community-based Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) studies on screening mammography and MRI performance and breast cancer outcomes in the 12 months following screening. This study does not incorporate radiologists’ examination interpretation or follow each examination for 12 months; instead, we examine biopsy intensity and yield in the 90 days following a screening examination (screening mammography alone vs screening MRI with or without screening mammography) in community settings by women’s PHBC and by breast cancer risk in women without PHBC.

Methods

This study included data from 6 BCSC registries (Carolina Mammography Registry [North Carolina], Kaiser Permanente Washington Registry [Washington State], Metro Chicago Breast Cancer Registry, New Hampshire Mammography Network, San Francisco Mammography Registry, and Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System). The BCSC registries collect information on examinations performed at participating facilities in their defined catchment areas and link this information to local pathology databases and state tumor registries or regional Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results programs to obtain population-based cancer data. Planned analyses required complete capture of benign and malignant biopsies and their results; therefore, we limited our sample to examinations from BCSC facilities with complete biopsy capture. Demographic and breast cancer risk factor data including age, first-degree family history, and time since last mammogram were collected using a self-reported questionnaire completed at each screening examination.

We included women with at least 1 screening digital mammogram or screening breast MRI from 2003 to 2013. We only included examinations with a radiologist’s indication of screening. For women without a PHBC, a screening examination (mammogram or MRI) was defined as a bilateral examination without the same type of imaging in the prior 9 months. For women with a PHBC, screening examinations included examinations in women without the following: prior bilateral mastectomy, imaging of the same type (mammogram or MRI) within the prior 60 days, or a breast cancer diagnosis within the prior 6 months.

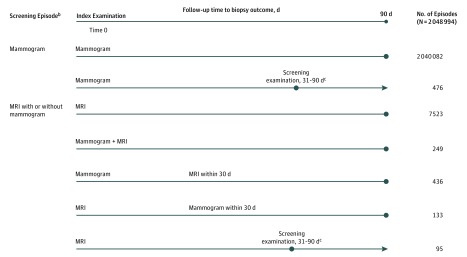

Analyses were conducted at the level of a screening episode (Figure 1). Each examination was followed for 90 days, unless there was another screening examination in the 90-day follow-up. The first examination within the episode is referred to as the index examination. In cases with 2 screening examinations within 30 days, we combined these into 1 episode followed for 90 days from the index examination. For screening examinations that occurred 31 to 90 days apart, the index examination was followed until the next screening examination more than 30 days later; the second screening examination started another screening episode with 90 days’ follow-up. Magnetic resonance imaging episodes included screening MRI with or without a screening mammogram because MRI alone really means MRI with adjunct mammography outside the 30-day window.

Figure 1. Screening Examinationsa With Follow-up Time and Associated Screening Episodeb Definitions.

aOnly examinations with radiologist indication of screening were considered. For women without a personal history of breast cancer (PHBC), a screening examination (mammogram or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) was defined as a bilateral examination and without imaging of the same type (mammogram or MRI) in the prior 9 months. For women with a PHBC, a screening examination was defined as an examination without the following: a prior bilateral mastectomy, imaging of the same type (mammogram or MRI) within the prior 60 days, or a diagnosis of cancer within 6 months before the screen.

bAll analyses were conducted at the level of a screening episode. Each screening examination was turned into a screening episode. Each examination was followed for 90 days, unless there was another screening examination in the 90-day follow-up. When a screening examination was followed within 30 days, these were rolled up to the first index screening examination and followed for 90 days from the index examination.

cScreening examination occurred 31 to 90 days after index examination. The second screening examination started another screening episode with 90 days’ follow-up.

All biopsies were linked with an individual screening episode to ensure that biopsy intensity was based on the most invasive biopsy performed (surgical biopsy greater than core biopsy greater than fine-needle aspiration) within the 90-day follow-up period. For 571 episodes (476 mammography and 95 MRI episodes), the follow-up period for biopsy ascertainment was truncated by another screening episode occurring within 31 to 90 days following the index examination. This ensured that a biopsy was only linked to 1 episode. Biopsy result was based on the most invasive finding found from any biopsy (invasive greater than ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS] greater than high-risk benign greater than benign). High-risk benign diagnoses included lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical hyperplasia; benign findings included usual ductal hyperplasia, fibroadenoma, cystosarcoma phyllodes, and calcifications. We separated high-risk benign diagnoses from other benign results because the clinical course of action may differ.

We calculated the BCSC 5-year risk score to evaluate imaging limited to women without a PHBC because the risk score is not designed for women with a PHBC. Risk scores were calculated for each episode using age, race, first-degree family history, breast biopsy history, and Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) breast density, and were categorized into low (<1.00%), average (1.00%-1.66%), intermediate (1.67%-2.49%), and high/very high (≥2.50%) risk. We used BI-RADS breast density interpretation from the index examination. Women’s addresses at each episode were geocoded using census block group and linked to median household income. Facility characteristics included profit status, academic affiliation, hospital-based location, and on-site MRI biopsy capability.

The BCSC registries and the Statistical Coordinating Center received institutional review board approval for active or passive consenting processes to enroll participants, link data, and perform analytic studies and a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality and other protections for the identities of participating women, physicians, and facilities.

Statistical Analysis

Frequency distributions of biopsy intensity, biopsy result within biopsy intensity, demographic characteristics (age at examination, race/ethnicity, income, rurality, BCSC risk, family history), mammography (examination year, density, time since last mammogram), and facility characteristics were examined and stratified by screening episode type and PHBC.

Unadjusted rates of each biopsy intensity (per 1000 episodes) were computed using the total number of screening episodes having a specific biopsy intensity divided by the total number of episodes. Unadjusted rates of biopsy yield (high-risk benign/DCIS/invasive) were computed within each biopsy intensity category (rate = total number of screening episodes linked to a specific biopsy intensity and result divided by the total number of screening episodes linked to a specific biopsy intensity). For age-adjusted rates, logistic regression models were fit for each outcome of interest (eg, core biopsy) including age as a covariate. Parameter estimates from each model were used to compute predicted probabilities based on age values in our sample. Finally, predicted probabilities were combined using weights based on the age distribution of the overall sample. We used the same approach to examine rates by BCSC risk category (low, average, intermediate, high/very high) for episodes in women without a PHBC. We combined core and surgical biopsy categories, and DCIS and invasive categories. Rates were stratified by screening modality and PHBC.

We conducted a propensity-matched sensitivity analysis to tightly control for potential confounding between women receiving different episode types. Predicted probability of MRI episodes was computed using a logistic regression model with BCSC registry, age, examination year, family history, and breast density. A SAS macro was used to perform 2 mammogram:1 MRI matching (without replacement) based on a 0.2–standard deviation caliper width of the propensity score logit. Unadjusted and age-adjusted biopsy intensity and finding rates were computed (on the subsets of matched episodes) separately by PHBC. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

We examined 2 048 994 imaging episodes from 812 164 women; the median number of episodes per woman was 2 for mammography and 1 for MRI (interquartile range, 1-3 overall). Mammogram episodes included 101 103 episodes in 36 318 women with PHBC and 1 939 455 episodes in 780 373 women without a PHBC; MRI episodes included 3763 episodes in 2323 women with PHBC and 4673 episodes in 3149 women without PHBC. Biopsy rate was higher following MRI than mammography: 6.3% (n = 236) vs 2.2% (n = 2231) in PHBC episodes and 10.5% (n = 489) vs 1.6% (n = 30 757) in episodes without a PHBC (Table 1). There was little difference in biopsy intensity by imaging modality regardless of PHBC status; most episodes had core biopsies as the most intensive biopsy.

Table 1. Screening Episode Modality by Biopsy Intensity and Biopsy Result Stratified by Women With a Personal History of Breast Cancer (PHBC).

| Parameter | No. (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Episodes | Episodes Among Women With PHBC | Episodes Among Women With No PHBCa | |||||||

| Total (N = 2 048 994) | Mammography Alone (n = 2 040 558) | MRI With or Without Mammographyb (n = 8436) | Total (n = 104 866) | Mammography Alone (n = 101 103) | MRI With or Without Mammography (n = 3763) | Total (n = 1 944 128) | Mammography Alone (n = 1 939 455) | MRI With or Without Mammography (n = 4673) | |

| Biopsy during follow-upc | |||||||||

| No | 2 015 281 (98.4) | 2 007 570 (98.4) | 7711 (91.4) | 102 399 (97.6) | 98 872 (97.8) | 3527 (93.7) | 1 912 882 (98.4) | 1 908 698 (98.4) | 4184 (89.5) |

| Yes | 33 713 (1.6) | 32 988 (1.6) | 725 (8.6) | 2467 (2.4) | 2231 (2.2) | 236 (6.3) | 31 246 (1.6) | 30 757 (1.6) | 489 (10.5) |

| Biopsy intensity | |||||||||

| FNA | 1954 (5.8) | 1919 (5.8) | 35 (4.8) | 112 (4.5) | 100 (4.5) | 12 (5.1) | 1842 (5.9) | 1819 (5.9) | 23 (4.7) |

| Core biopsyd | 25 226 (74.8) | 24 706 (74.9) | 520 (71.7) | 1694 (68.7) | 1530 (68.6) | 164 (69.5) | 23 532 (75.3) | 23 176 (75.4) | 356 (72.8) |

| Surgical biopsye | 6533 (19.4) | 6363 (19.3) | 170 (23.4) | 661 (26.8) | 601 (26.9) | 60 (25.4) | 5872 (18.8) | 5762 (18.7) | 110 (22.5) |

| Biopsy resultf,g by intensityh | |||||||||

| FNA | |||||||||

| Benign | 1862 (95.3) | 1834 (95.6) | 28 (80.0) | 91 (81.3) | 83 (83.0) | 8 (66.7) | 1771 (96.1) | 1751 (96.3) | 20 (87.0) |

| High-risk benign | 14 (0.7) | 13 (0.7) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 13 (0.7) | 13 (0.7) | 0 |

| DCIS | 13 (0.7) | 13 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 12 (0.7) | 12 (0.7) | 0 |

| Invasive | 65 (3.3) | 59 (3.1) | 6 (17.1) | 19 (17.0) | 16 (16.0) | 3 (25.0) | 46 (2.5) | 43 (2.4) | 3 (13.0) |

| Core biopsy | |||||||||

| Benign | 19 216 (76.2) | 18 780 (76.0) | 436 (83.8) | 1063 (62.8) | 939 (61.4) | 124 (75.6) | 18 153 (77.1) | 17 841 (77.0) | 312 (87.6) |

| High-risk benign | 837 (3.3) | 819 (3.3) | 18 (3.5) | 68 (4.0) | 60 (3.9) | 8 (4.9) | 769 (3.3) | 759 (3.3) | 10 (2.8) |

| DCIS | 1699 (6.7) | 1677 (6.8) | 22 (4.2) | 191 (11.3) | 178 (11.6) | 13 (7.9) | 1508 (6.4) | 1499 (6.5) | 9 (2.5) |

| Invasive | 3474 (13.8) | 3430 (13.9) | 44 (8.5) | 372 (22.0) | 353 (23.1) | 19 (11.6) | 3102 (13.2) | 3077 (13.3) | 25 (7.0) |

| Surgical biopsy | |||||||||

| Benign | 2344 (35.9) | 2261 (35.5) | 83 (48.8) | 172 (26.0) | 144 (24.0) | 28 (46.7) | 2172 (37.0) | 2117 (36.7) | 55 (50.0) |

| High-risk benign | 774 (11.8) | 740 (11.6) | 34 (20.0) | 47 (7.1) | 37 (6.2) | 10 (16.7) | 727 (12.4) | 703 (12.2) | 24 (21.8) |

| DCIS | 1079 (16.5) | 1061 (16.7) | 18 (10.6) | 106 (16.0) | 99 (16.5) | 7 (11.7) | 973 (16.6) | 962 (16.7) | 11 (10.0) |

| Invasive | 2336 (35.8) | 2301 (36.2) | 35 (20.6) | 336 (50.8) | 321 (53.4) | 15 (25.0) | 2000 (34.1) | 1980 (34.4) | 20 (18.2) |

Abbreviations: DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Includes 620 078 episodes with unknown PHBC.

Includes 818 MRI with mammography (436 with mammography first then MRI, 133 with MRI then mammography, 249 with mammography and MRI same day).

Follow-up period for biopsy/FNA = 90 d after index screen (and prior to start of next episode, if one exists).

Includes 373 episodes with FNA also during follow-up.

Includes 4052 episodes with FNA and/or core biopsy also during follow-up.

Biopsy result is based on most invasive result (invasive greater than DCIS greater than benign high-risk greater than benign) found from all biopsy/FNA procedures during follow-up.

High-risk benign = lobular carcinoma in situ or atypical hyperplasia; benign = ductal hyperplasia, fibroadenoma, cystosarcoma phyllodes, calcifications, benign findings.

Biopsy intensity is based on the highest intensity biopsy (surgical biopsy greater than core biopsy greater than FNA) found during follow-up.

Compared with MRI, mammography episodes with core and surgical biopsies had a higher yield of DCIS and invasive breast cancer and lower benign biopsy rates regardless of PHBC. Among episodes with a PHBC, 531 (34.7%) of core biopsies associated with a mammography episode resulted in a DCIS or invasive cancer diagnosis compared with 32 (19.5%) associated with an MRI episode; for surgical biopsies the percent was higher but had the same comparative relationship. For episodes without a PHBC, overall DCIS and invasive cancer rates were lower than among episodes with a PHBC, but we observed the same comparative relationship.

Compared with mammography episodes, MRI episodes (Table 2) were more likely to occur in women with a first-degree family history of breast cancer, particularly among episodes without a PHBC (72.3% vs 16.4% mammography only). Higher breast density (heterogeneously or extremely dense) was more likely in women with MRI vs mammography episodes. The BCSC 5-year breast cancer risk was higher in MRI episodes.

Table 2. Characteristics by Screening Modality,a Stratified by Personal History of Breast Cancer (PHBC).

| Parameter | All Episodes | Episodes Among Women With PHBC | Episodes Among Women With No PHBC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 2 048 994) | Mammography Alone (n = 2 040 558) | MRI With or Without Mammography (n = 8436) | Total (n = 104 866) | Mammography Alone (n = 101 103) | MRI With or Without Mammography (n = 3763) | Total (n = 1 944 128) | Mammography Alone (n = 1 939 455) | MRI With or Without Mammography (n = 4673) | |

| Age at screening examination, y | |||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 56 (48-66) | 56 (48-66) | 52 (44-59) | 66 (58-75) | 66 (58-75) | 55 (49-62) | 56 (48-65) | 56 (48-65) | 49 (42-56) |

| No. (%) | |||||||||

| <30 | 1417 (0.1) | 1232 (0.1) | 185 (2.2) | 45 (0) | 27 (0) | 18 (0.5) | 1372 (0.1) | 1205 (0.1) | 167 (3.6) |

| 30-39 | 49 836 (2.4) | 48 919 (2.4) | 917 (10.9) | 841 (0.8) | 648 (0.6) | 193 (5.1) | 48 995 (2.5) | 48 271 (2.5) | 724 (15.5) |

| 40-49 | 544 120 (26.6) | 541 689 (26.5) | 2431 (28.8) | 7949 (7.6) | 7111 (7.0) | 838 (22.3) | 536 171 (27.6) | 534 578 (27.6) | 1593 (34.1) |

| 50-59 | 613 216 (29.9) | 610 275 (29.9) | 2941 (34.9) | 22 981 (21.9) | 21 513 (21.3) | 1468 (39.0) | 590 235 (30.4) | 588 762 (30.4) | 1473 (31.5) |

| 60-64 | 266 220 (13.0) | 265 241 (13.0) | 979 (11.6) | 15 647 (14.9) | 15 062 (14.9) | 585 (15.5) | 250 573 (12.9) | 250 179 (12.9) | 394 (8.4) |

| 65-69 | 211 513 (10.3) | 210 926 (10.3) | 587 (7.0) | 16 134 (15.4) | 15 755 (15.6) | 379 (10.1) | 195 379 (10.0) | 195 171 (10.1) | 208 (4.5) |

| 70-79 | 261 239 (12.7) | 260 905 (12.8) | 334 (4.0) | 25 458 (24.3) | 25 229 (25.0) | 229 (6.1) | 235 781 (12.1) | 235 676 (12.2) | 105 (2.2) |

| ≥80 | 101 433 (5.0) | 101 371 (5.0) | 62 (0.7) | 15 811 (15.1) | 15 758 (15.6) | 53 (1.4) | 85 622 (4.4) | 85 613 (4.4) | 9 (0.2) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | |||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1 396 942 (73.7) | 1 390 419 (73.7) | 6523 (84.1) | 78 728 (80.5) | 75 769 (80.4) | 2959 (83.0) | 1 318 214 (73.3) | 1 314 650 (73.3) | 3564 (85.1) |

| Black | 201 975 (10.7) | 201 765 (10.7) | 210 (2.7) | 8308 (8.5) | 8222 (8.7) | 86 (2.4) | 193 667 (10.8) | 193 543 (10.8) | 124 (3.0) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 4048 (0.2) | 4032 (0.2) | 16 (0.2) | 200 (0.2) | 192 (0.2) | 8 (0.2) | 3848 (0.2) | 3840 (0.2) | 8 (0.2) |

| Asian | 171 054 (9.0) | 170 549 (9.0) | 505 (6.5) | 6288 (6.4) | 5994 (6.4) | 294 (8.2) | 164 766 (9.2) | 164 555 (9.2) | 211 (5.0) |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific islander | 999 (0.1) | 994 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) | 58 (0.1) | 56 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 941 (0.1) | 938 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) |

| Hispanic | 86 582 (4.6) | 86 316 (4.6) | 266 (3.4) | 2577 (2.6) | 2460 (2.6) | 117 (3.3) | 84 005 (4.7) | 83 856 (4.7) | 149 (3.6) |

| Other/mixed | 33 632 (1.8) | 33 405 (1.8) | 227 (2.9) | 1655 (1.7) | 1555 (1.6) | 100 (2.8) | 31 977 (1.8) | 31 850 (1.8) | 127 (3.0) |

| Unknown | 153 762 (7.5) | 153 078 (7.5) | 684 (8.1) | 7052 (6.7) | 6855 (6.8) | 197 (5.2) | 146 710 (7.6) | 146 223 (7.5) | 487 (10.4) |

| Census block group income, No. (%), $ | |||||||||

| ≤36 000 | 132 463 (7.6) | 132 196 (7.6) | 267 (4.2) | 8426 (9.2) | 8311 (9.4) | 115 (4.0) | 124 037 (7.5) | 123 885 (7.5) | 152 (4.4) |

| 36 001-47 500 | 220 440 (12.7) | 219 964 (12.7) | 476 (7.5) | 12 320 (13.5) | 12 104 (13.7) | 216 (7.5) | 208 120 (12.6) | 207 860 (12.6) | 260 (7.5) |

| 47 501-64 600 | 419 973 (24.1) | 418 428 (24.1) | 1545 (24.4) | 22 718 (24.8) | 22 018 (24.8) | 700 (24.3) | 397 255 (24.1) | 396 410 (24.1) | 845 (24.4) |

| ≥64 601 | 967 938 (55.6) | 963 885 (55.6) | 4053 (63.9) | 48 027 (52.5) | 46 181 (52.1) | 1846 (64.2) | 919 911 (55.8) | 917 704 (55.8) | 2207 (63.7) |

| Unknown | 308 180 (15.0) | 306 085 (15.0) | 2095 (24.8) | 13 375 (12.8) | 12 489 (12.4) | 886 (23.6) | 294 805 (15.2) | 293 596 (15.1) | 1209 (25.9) |

| Rurality, No. (%) | |||||||||

| Urban focused | 1 271 973 (76.3) | 1 266 613 (76.3) | 5360 (77.3) | 64 972 (71.2) | 62 529 (71.0) | 2443 (77.7) | 1 207 001 (76.6) | 1 204 084 (76.6) | 2917 (76.9) |

| Large rural | 196 746 (11.8) | 196 054 (11.8) | 692 (10.0) | 12 012 (13.2) | 11 715 (13.3) | 297 (9.4) | 184 734 (11.7) | 184 339 (11.7) | 395 (10.4) |

| Small rural | 94 798 (5.7) | 94 345 (5.7) | 453 (6.5) | 6909 (7.6) | 6705 (7.6) | 204 (6.5) | 87 889 (5.6) | 87 640 (5.6) | 249 (6.6) |

| Isolated rural | 103 176 (6.2) | 102 745 (6.2) | 431 (6.2) | 7300 (8.0) | 7101 (8.1) | 199 (6.3) | 95 876 (6.1) | 95 644 (6.1) | 232 (6.1) |

| Unknown | 382 301 (18.7) | 380 801 (18.7) | 1500 (17.8) | 13 673 (13.0) | 13 053 (12.9) | 620 (16.5) | 368 628 (19.0) | 367 748 (19.0) | 880 (18.8) |

| Year of screening examinations, No. (%) | |||||||||

| 2003 | 16 226 (0.8) | 16 202 (0.8) | 24 (0.3) | 1031 (1.0) | 1020 (1.0) | 11 (0.3) | 15 195 (0.8) | 15 182 (0.8) | 13 (0.3) |

| 2004 | 31 764 (1.6) | 31 736 (1.6) | 28 (0.3) | 1782 (1.7) | 1765 (1.7) | 17 (0.5) | 29 982 (1.5) | 29 971 (1.5) | 11 (0.2) |

| 2005 | 69 440 (3.4) | 69 277 (3.4) | 163 (1.9) | 3225 (3.1) | 3148 (3.1) | 77 (2.0) | 66 215 (3.4) | 66 129 (3.4) | 86 (1.8) |

| 2006 | 124 356 (6.1) | 123 824 (6.1) | 532 (6.3) | 5210 (5.0) | 4995 (4.9) | 215 (5.7) | 119 146 (6.1) | 118 829 (6.1) | 317 (6.8) |

| 2007 | 180 389 (8.8) | 179 567 (8.8) | 822 (9.7) | 7312 (7.0) | 6953 (6.9) | 359 (9.5) | 173 077 (8.9) | 172 614 (8.9) | 463 (9.9) |

| 2008 | 263 578 (12.9) | 262 520 (12.9) | 1058 (12.5) | 11 805 (11.3) | 11 345 (11.2) | 460 (12.2) | 251 773 (13.0) | 251 175 (13.0) | 598 (12.8) |

| 2009 | 350 118 (17.1) | 349 117 (17.1) | 1001 (11.9) | 15 894 (15.2) | 15 437 (15.3) | 457 (12.1) | 334 224 (17.2) | 333 680 (17.2) | 544 (11.6) |

| 2010 | 349 365 (17.1) | 347 969 (17.1) | 1396 (16.5) | 17 413 (16.6) | 16 752 (16.6) | 661 (17.6) | 331 952 (17.1) | 331 217 (17.1) | 735 (15.7) |

| 2011 | 303 849 (14.8) | 302 436 (14.8) | 1413 (16.7) | 16 749 (16.0) | 16 115 (15.9) | 634 (16.8) | 287 100 (14.8) | 286 321 (14.8) | 779 (16.7) |

| 2012 | 223 456 (10.9) | 222 157 (10.9) | 1299 (15.4) | 14 871 (14.2) | 14 291 (14.1) | 580 (15.4) | 208 585 (10.7) | 207 866 (10.7) | 719 (15.4) |

| 2013 | 136 453 (6.7) | 135 753 (6.7) | 700 (8.3) | 9574 (9.1) | 9282 (9.2) | 292 (7.8) | 126 879 (6.5) | 126 471 (6.5) | 408 (8.7) |

| BCSC 5-y risk (for episodes without PHBC) | |||||||||

| Median (IQR) | … | … | … | … | … | … | 1.24 (0.82-1.72) | 1.24 (0.82-1.72) | 1.78 (1.11-2.67) |

| No. (%) | |||||||||

| Low (0-1.00%) | … | … | … | … | … | … | 566 602 (35.0) | 565 870 (35.1) | 732 (20.4) |

| Average (1.00%-1.66%) | … | … | … | … | … | … | 623 622 (38.5) | 622 706 (38.6) | 916 (25.6) |

| Intermediate (1.67%-2.49%) | … | … | … | … | … | … | 301 405 (18.6) | 300 499 (18.6) | 906 (25.3) |

| High/very high (≥2.50%) | … | … | … | … | … | … | 126 335 (7.8) | 125 308 (7.8) | 1027 (28.7) |

| Unknown | … | … | … | … | ... | … | 326 164 (16.8) | 325 072 (16.8) | 1092 (23.4) |

| First-degree family history of breast cancer, No. (%) | |||||||||

| Yes | 342 948 (16.9) | 338 729 (16.8) | 4219 (53.3) | 25 437 (24.4) | 24 331 (24.2) | 1106 (30.6) | 317 511 (16.5) | 314 398 (16.4) | 3113 (72.3) |

| No | 1 684 839 (83.1) | 1 681 135 (83.2) | 3704 (46.7) | 78 745 (75.6) | 76 236 (75.8) | 2509 (69.4) | 1 606 094 (83.5) | 1 604 899 (83.6) | 1195 (27.7) |

| Unknown | 21 207 (1.0) | 20 694 (1.0) | 513 (6.1) | 684 (0.7) | 536 (0.5) | 148 (3.9) | 20 523 (1.1) | 20 158 (1.0) | 365 (7.8) |

| BI-RADS density, No. (%) | |||||||||

| Fatty | 197 856 (10.3) | 197 527 (10.3) | 329 (4.8) | 11 237 (11.6) | 11 125 (11.8) | 112 (4.0) | 186 619 (10.2) | 186 402 (10.2) | 217 (5.4) |

| Scattered fibroglandular | 824 351 (42.8) | 822 353 (42.8) | 1998 (29.2) | 48 525 (50.1) | 47 625 (50.6) | 900 (31.8) | 775 826 (42.4) | 774 728 (42.4) | 1098 (27.3) |

| Heterogeneously dense | 752 647 (39.1) | 749 448 (39.0) | 3199 (46.7) | 33 263 (34.3) | 31 878 (33.9) | 1385 (48.9) | 719 384 (39.3) | 717 570 (39.3) | 1814 (45.1) |

| Extremely dense | 151 288 (7.9) | 149 961 (7.8) | 1327 (19.4) | 3920 (4.0) | 3487 (3.7) | 433 (15.3) | 147 368 (8.1) | 146 474 (8.0) | 894 (22.2) |

| Unknown | 122 852 (6.0) | 121 269 (5.9) | 1583 (18.8) | 7921 (7.6) | 6988 (6.9) | 933 (24.8) | 114 931 (5.9) | 114 281 (5.9) | 650 (13.9) |

| Onsite MRI biopsy capabilityb | |||||||||

| Yes | 953 593 (49.9) | 946 171 (49.7) | 7422 (93.4) | 54 041 (53.2) | 50 688 (51.7) | 3353 (94.8) | 899 552 (49.7) | 895 483 (49.6) | 4069 (92.2) |

| No | 958 941 (50.1) | 958 414 (50.3) | 527 (6.6) | 47 503 (46.8) | 47 318 (48.3) | 185 (5.2) | 911 438 (50.3) | 911 096 (50.4) | 342 (7.8) |

| Unknown | 110 227 (5.5) | 110 148 (5.5) | 79 (1.0) | 1755 (1.7) | 1713 (1.7) | 42 (1.2) | 108 472 (5.7) | 108 435 (5.7) | 37 (0.8) |

| Time since last screening examination, No. (%), y | |||||||||

| No previous mammogram | 73 429 (3.8) | 73 387 (3.8) | 42 (0.5) | 182 (0.2) | 177 (0.2) | 5 (0.1) | 73 247 (4.0) | 73 210 (4.0) | 37 (0.9) |

| <1 | 33 421 (1.7) | 27 453 (1.4) | 5968 (75.2) | 14 604 (14.1) | 11 893 (11.9) | 2711 (74.8) | 18 817 (1.0) | 15 560 (0.8) | 3257 (75.6) |

| 1-2 | 1 677 924 (86.0) | 1 676 246 (86.3) | 1678 (21.2) | 86 999 (83.7) | 86 197 (85.9) | 802 (22.1) | 1 590 925 (86.1) | 1 590 049 (86.3) | 876 (20.3) |

| 3-4 | 105 680 (5.4) | 105 548 (5.4) | 132 (1.7) | 1456 (1.4) | 1404 (1.4) | 52 (1.4) | 104 224 (5.6) | 104 144 (5.7) | 80 (1.9) |

| ≥5 | 60 763 (3.1) | 60 650 (3.1) | 113 (1.4) | 681 (0.7) | 629 (0.6) | 52 (1.4) | 60 082 (3.3) | 60 021 (3.3) | 61 (1.4) |

| Unknown | 97 777 (4.8) | 97 274 (4.8) | 503 (6.0) | 944 (0.9) | 803 (0.8) | 141 (3.8) | 96 833 (5.0) | 96 471 (5.0) | 362 (7.8) |

Abbreviations: BI-RADS, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System; BCSC, Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; IQR, interquartile range; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Screening modality is based on information within 30 d of the index examination.

Numbers and percentages based on examinations from registries that collect this facility characteristic; 1 registry is excluded.

The same patterns were observed regardless of PHBC, with higher biopsy rates and intensity for MRI vs mammography episodes (Table 3). Age-adjusted core and surgical biopsy rates (per 1000 episodes) were nearly double (57.1; 95% CI, 50.3-65.1) following MRI compared with mammography (23.6; 95% CI, 22.4-24.8) in women with a PHBC, with larger differences in women without a PHBC. High-risk benign lesions were more commonly identified following MRI compared with mammography regardless of PHBC; confidence intervals overlapped in women with a PHBC but not in women without a PHBC. In contrast, DCIS and invasive yield (per 1000 episodes) was significantly higher following mammography compared with MRI episodes in women with a PHBC (mammography, 404.6; 95% CI, 381.2-428.8; MRI, 267.6; 95% CI, 208.0-337.8) and nonsignificantly higher, but in the same direction, in women without a PHBC (mammography, 279.3; 95% CI, 274.2-284.4; MRI, 214.6; 95% CI, 158.7-280.8).

Table 3. Unadjusted and Age-Adjusted Rates of Biopsy Intensity and Biopsy Result by Screening Modality and Personal History of Breast Cancer (PHBC).

| Parameter | Episodes Among Women With PHBC | Episodes Among Women With No PHBCa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (Denominator) | Rate (95% CI) per 1000 Episodes | No. (Denominator) | Rate (95% CI) per 1000 Episodes | |||

| Unadjusted | Age Adjusted | Unadjusted | Age Adjusted | |||

| Biopsy Intensity | ||||||

| Mammography | ||||||

| FNA | 100 (101 103) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | … | 1819 (1 939 455) | 0.9 (0.9-1.0) | … |

| Core biopsy | 1530 (101 103) | 15.1 (14.4-15.9) | 16.8 (15.8-17.9) | 23 176 (1 939 455) | 11.9 (11.8-12.1) | 11.9 (11.7-12.0) |

| Surgical biopsy | 601 (101 103) | 5.9 (5.5-6.4) | 6.8 (6.1-7.5) | 5762 (1 939 455) | 3.0 (2.9-3.0) | 3.0 (2.9-3.1) |

| Core + surgical | 2131 (101 103) | 21.1 (20.2-22.0) | 23.6 (22.4-24.8) | 28 938 (1 939 455) | 14.9 (14.8-15.1) | 14.9 (14.7-15.0) |

| MRI | ||||||

| FNA | 12 (3763) | 3.2 (1.6-5.6) | … | 23 (4673) | 4.9 (3.1-7.4) | … |

| Core biopsy | 164 (3763) | 43.6 (37.3-50.6) | 41.6 (35.8-48.6) | 356 (4673) | 76.2 (68.7-84.2) | 61.1 (53.8-69.7) |

| Surgical biopsy | 60 (3763) | 15.9 (12.2-20.5) | 15.5 (12.1-20.3) | 110 (4673) | 23.5 (19.4-28.3) | 24.3 (19.2-31.3) |

| Core + surgical | 224 (3763) | 59.5 (52.2-67.6) | 57.1 (50.3-65.1) | 466 (4673) | 99.7 (91.3-108.7) | 84.7 (75.9-94.9) |

| Biopsy Resultb | ||||||

| Mammography and core or surgical biopsy | ||||||

| High-risk benign | 97 (2131) | 45.5 (37.1-55.2) | 52.4 (42.0-66.1) | 1462 (289 38) | 50.5 (48.0-53.1) | 50.2 (47.7-52.8) |

| DCIS | 277 (2131) | 130.0 (116.0-145.0) | 137.4 (120.9-156.3) | 2461 (28 938) | 85.0 (81.9-88.3) | 89.0 (85.7-92.5) |

| Invasive | 674 (2131) | 316.3 (296.6-336.5) | 269.5 (249.7-290.6) | 5057 (28 938) | 174.8 (170.4-179.2) | 190.1 (185.7-194.7) |

| DCIS + invasive | 951 (2131) | 446.3 (425.0-467.7) | 404.6 (381.2-428.8) | 7518 (28 938) | 259.8 (254.8-264.9) | 279.3 (274.2-284.4) |

| MRI and core or surgical biopsy | ||||||

| High-risk benign | 18 (224) | 80.4 (48.3-124.0) | 75.3 (48.0-126.8) | 34 (466) | 73.0 (51.1-100.5) | 122.7 (79.1-186.9) |

| DCIS | 20 (224) | 89.3 (55.4-134.5) | 114.0 (73.3-176.6) | 20 (466) | 42.9 (26.4-65.5) | 76.3 (42.7-139.3) |

| Invasive | 34 (224) | 151.8 (107.5-205.6) | 156.8 (113.0-220.6) | 45 (466) | 96.6 (71.3-127.1) | 142.4 (97.4-206.9) |

| DCIS + invasive | 54 (224) | 241.1 (186.6-302.5) | 267.6 (208.0-337.8) | 65 (466) | 139.5 (109.3-174.3) | 214.6 (158.7-280.8) |

Abbreviations: DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; ellipses, not estimated due to small sample size; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Includes 620 078 episodes with unknown PHBC.

Rate (95% CI) per 1000 episodes with core or surgical biopsy.

Propensity matching yielded comparable populations (eTable 1 in the Supplement) to the main sample with 2 notable differences: a much larger proportion of mammogram episodes having a family history in women without a PHBC, and higher density distributions in mammogram episodes in women with and without a PHBC. There were few differences in the unadjusted and age-adjusted propensity-matched results compared with the main analysis. Continued higher DCIS and invasive cancers yield was observed in mammogram episodes with larger differences in episodes without PHBC (eTable 2 in the Supplement). However, high-risk benign findings were no longer higher in MRI episodes in women with a PHBC, which may be due to propensity matching leading to a higher density distribution in a smaller sample of mammogram episodes.

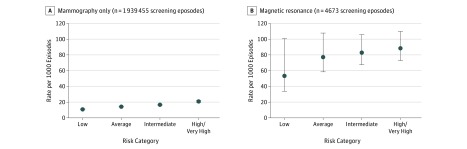

Among women without PHBC, age-adjusted core and surgical biopsy rates following mammography and MRI episodes were stratified by BCSC 5-year breast cancer risk (Figure 2). Among mammography episodes, age-adjusted biopsy rates increased with increasing risk. Biopsy rates were approximately 5-fold higher for MRI compared with mammography episodes across BCSC risk groups. Age-adjusted biopsy rates in MRI episodes increased by risk category, but with overlapping confidence intervals.

Figure 2. Age-Adjusted Rate of Core and Surgical Breast Biopsies by Screening Modality and Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium 5-Year Breast Cancer Risk Among 783 522 Women Without a Personal History of Breast Cancer.

Discussion

We evaluated biopsy rates by intensity and yield within 90 days following screening mammography and MRI episodes among women with and without a PHBC. After accounting for age, we observed more than 2-fold higher core and surgical biopsy rates following MRI among women with a PHBC and more than 5-fold higher core and surgical biopsy rates following MRI in women without, compared with mammography. Regardless of PHBC status, rates of DCIS and invasive cancer diagnosed within 90 days were higher following mammography vs MRI, with significantly higher rates following mammography among women with a PHBC. In contrast, higher rates of high-risk benign lesions were detected following MRI compared with mammography regardless of PHBC; this was not observed in our propensity-matched sensitivity analysis. Differences in core and surgical biopsy rates by imaging modality were not explained by breast cancer risk because higher biopsy rates were observed across all risk groups following MRI compared with mammography. We expected and observed higher DCIS and invasive cancer rates with increasing biopsy intensity. We also expected higher biopsy rates following MRI because of its higher sensitivity and lower specificity compared with mammography. While positive findings on mammography may be resolved with subsequent diagnostic mammography and/or ultrasound, positive screening MRI results are usually resolved with short-interval follow-up MRI or biopsy.

Many individuals believe that reports of the rapid increase in use of MRI mean that MRI is overused. The reality is that most women with a PHBC, as well as high-risk women without a PHBC, do not receive breast MRI in community settings. This is consistent with the recommendation that women not receive routine MRI screening except those meeting high-risk criteria for increased breast cancer surveillance. The use of MRI may facilitate identifying high-risk women eligible for genetic counseling and/or primary prevention by identifying high-risk benign lesions that would increase 5-year risk to greater than 3%, but guidelines have not been established to support this practice. Our findings support the need to define and identify the appropriate selection of women for MRI screening to minimize the harms in low-risk women. Better understanding clinical pathway patterns of multimodality screening and their associated outcomes could help to simultaneously improve the patient care experience and the health of populations while reducing per capita costs for achieving high-quality outcomes for high-risk populations and among the growing population of women with a PHBC.

Our results should not be compared with traditional screening performance measures, which take into account examination interpretation with 12 months’ follow-up for cancer outcomes. We included any biopsy occurring within a 90-day period following a screening examination regardless of examination interpretation; thus, these results are not comparable to cancer detection rates, which include interpretation and 12-month follow-up. Multimodality screening with mammography and MRI is recommended for women with at least 20% lifetime breast cancer risk and some women with a PHBC. Nearly all women who receive screening MRI receive it as an adjunct to mammography. However, there is substantial variability as to how adjunct imaging occurs—from same day with MRI or mammography first to a 6-month alternating interval. Differences in timing between screening examinations are driven by multiple factors including clinician preference and availability/access and were major drivers in our intentional analytic strategy to focus on screening episodes with a limited biopsy follow-up period. We defined our MRI episodes to include MRI in combination with screening mammography within 30 days of one another and also included MRI alone with no adjunct screening, in part due to small sample size, but also due to the underlying clinical relevance because MRI alone really means MRI with adjunct mammography outside the 30-day window.

Despite reports demonstrating rapid increases in the uptake of screening MRI, we did not see big changes in MRI episodes by year regardless of PHBC status; only a small percentage of imaging episodes in women with a PHBC (<4%) or among high-risk women (<1%) were MRIs. We found important differences regardless of PHBC in who received MRI, including younger age and other demographic characteristics. Age adjustment was critical to help account for differences in biopsy rates and findings by imaging modality and will be important for other evaluations comparing imaging strategies and performance. Interestingly, our propensity-matched analyses yielded results similar to those of our full sample. We were able to evaluate whether BCSC 5-year risk explained differences in biopsy intensity and findings, but only among women without a PHBC. Genetic mutation data are not routinely available in the BCSC, which would likely improve our ability to characterize the underlying risk of women and appropriateness of screening MRI. It remains possible that our analyses have residual confounding by risk, but it is unlikely to account for the magnitude of difference observed by imaging modality; however, we are reassured by the fact that our propensity-matched sensitivity analyses yielded similar results.

Important strengths include the inclusion of biopsy intensity and findings from 2 040 558 mammogram episodes and 8436 MRI episodes from 136 BCSC community and academic radiology facilities linked to pathology databases, as well as state and regional tumor registries. Our study includes a geographically and racially representative US population sample, likely reflecting US clinical radiology practice.

Limitations

We acknowledge that there may be misattribution of the most significant pathological findings with the most invasive biopsy finding, but we believe that it would be unlikely for women to undergo a more intensive biopsy after identifying DCIS or invasive cancer. There were a few DCIS and invasive findings associated with fine-needle aspiration, suggesting that we may have missed some additional biopsies in this small number of cases. We were also unable to evaluate biopsy guidance, which we acknowledge as clinically important.

There is hope that tomosynthesis will decrease the rate of false-positive results and improve biopsy yield. However, in addition to increased radiation dose, acquisition and interpretation time, and cost, tomosynthesis has been shown in nonrandomized studies to improve cancer detection and recall rates, but potentially increase benign biopsy rates. We were unable to evaluate tomosynthesis in this study.

Conclusions

In women with and without a PHBC, we observed clinically and statistically higher biopsy rates in the 90 days following screening MRI compared with mammography episodes, which resulted in lower rates of DCIS and invasive cancer findings following MRI. Higher biopsy rates and lower cancer yield following MRI were not explained after accounting for age or 5-year breast cancer risk or propensity-matched analyses. Further work is needed to identify women who will benefit from screening MRI to ensure an acceptable benefit-to-harm ratio. Women who undergo screening MRI should also be notified that their likelihood of undergoing a core or surgical breast biopsy is significantly higher than for women undergoing mammography alone, with a lower likelihood of clinically actionable findings.

eTable 1. Distribution of covariates in the propensity score matched sample (matching was done separately based on personal history of breast cancer)

eTable 2. Propensity score matched unadjusted and age-adjusted rates of biopsy intensity and biopsy result by screening modality and history of breast cancer

References

- 1.Esserman L, Shieh Y, Thompson I. Rethinking screening for breast cancer and prostate cancer. JAMA. 2009;302(15):1685-1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):1998-2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myers ER, Moorman P, Gierisch JM, et al. Benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1615-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson HD, Pappas M, Cantor A, Griffin J, Daeges M, Humphrey L. Harms of breast cancer screening: systematic review to update the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):256-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marmot MG. Sorting through the arguments on breast screening. JAMA. 2013;309(24):2553-2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al. ; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group . American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(2):75-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Breast Cancer. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Vol 1 Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wernli KJ, DeMartini WB, Ichikawa L, et al. ; Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium . Patterns of breast magnetic resonance imaging use in community practice. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):125-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stout NK, Nekhlyudov L, Li L, et al. Rapid increase in breast magnetic resonance imaging use: trends from 2000 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):114-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haas JS, Hill DA, Wellman RD, et al. Disparities in the use of screening magnetic resonance imaging of the breast in community practice by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Cancer. 2016;122(4):611-617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):611-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buist DS, Abraham LA, Barlow WE, et al. ; Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium . Diagnosis of second breast cancer events after initial diagnosis of early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124(3):863-873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houssami N, Abraham LA, Miglioretti DL, et al. Accuracy and outcomes of screening mammography in women with a personal history of early-stage breast cancer. JAMA. 2011;305(8):790-799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houssami N, Abraham LA, Kerlikowske K, et al. Risk factors for second screen-detected or interval breast cancers in women with a personal history of breast cancer participating in mammography screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(5):946-961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JM, Buist DS, Houssami N, et al. Five-year risk of interval-invasive second breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(7):djv109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JM, Ichikawa L, Valencia E, et al. Performance benchmarks for screening breast MR imaging in community practice. Radiology. 2017;285(1):44-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lehman CD, Arao RF, Sprague BL, et al. National performance benchmarks for modern screening digital mammography: update from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Radiology. 2017;283(1):49-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium website. 2016. http://www.bcsc-research.org/. Accessed June 11, 2017.

- 19.Ballard-Barbash R, Taplin SH, Yankaskas BC, et al. Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium: a national mammography screening and outcomes database. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169(4):1001-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.BCSC Glossary of Terms, Version 2. 2017. http://www.bcsc-research.org/data/bcsc_data_definitions_version2_final__2017.pdf. Accessed July 31, 2017.

- 21.Menes TS, Kerlikowske K, Lange J, Jaffer S, Rosenberg R, Miglioretti DL. Subsequent breast cancer risk following diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia on needle biopsy. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):36-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menes TS, Rosenberg R, Balch S, Jaffer S, Kerlikowske K, Miglioretti DL. Upgrade of high-risk breast lesions detected on mammography in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Am J Surg. 2014;207(1):24-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tice JA, O’Meara ES, Weaver DL, Vachon C, Ballard-Barbash R, Kerlikowske K. Benign breast disease, mammographic breast density, and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(14):1043-1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiluk JV, Acs G, Hoover SJ. High-risk benign breast lesions: current strategies in management. Cancer Control. 2007;14(4):321-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tice JA, Miglioretti DL, Li CS, Vachon CM, Gard CC, Kerlikowske K. Breast density and benign breast disease: risk assessment to identify women at high risk of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(28):3137-3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coca-Perraillon M. Local and global optimal propensity score matching. Paper presented at: SAS Global Forum; April 16-19, 2007; Orlando, Florida. Paper 185-2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svahn TM, Houssami N, Sechopoulos I, Mattsson S. Review of radiation dose estimates in digital breast tomosynthesis relative to those in two-view full-field digital mammography. Breast. 2015;24(2):93-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert FJ, Tucker L, Gillan MG, et al. The TOMMY trial: a comparison of tomosynthesis with digital mammography in the UK NHS Breast Screening Programme—a multicentre retrospective reading study comparing the diagnostic performance of digital breast tomosynthesis and digital mammography with digital mammography alone. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(4):i-xxv, 1-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zuley ML, Guo B, Catullo VJ, et al. Comparison of two-dimensional synthesized mammograms versus original digital mammograms alone and in combination with tomosynthesis images. Radiology. 2014;271(3):664-671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardesty LA. Issues to consider before implementing digital breast tomosynthesis into a breast imaging practice. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(3):681-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee CI, Lehman CD. Digital breast tomosynthesis and the challenges of implementing an emerging breast cancer screening technology into clinical practice. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;10(12):913-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedewald SM, Rafferty EA, Rose SL, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2499-2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skaane P. Breast cancer screening with digital breast tomosynthesis. Breast Cancer. 2017;24(1):32-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Distribution of covariates in the propensity score matched sample (matching was done separately based on personal history of breast cancer)

eTable 2. Propensity score matched unadjusted and age-adjusted rates of biopsy intensity and biopsy result by screening modality and history of breast cancer