Abstract

National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs) provide independent, evidence-informed advice to assist their governments in immunization policy formation. However, many NITAGs face challenges in fulfilling their roles. Hence the many requests for formation of a network linking NITAGs together so they can learn from each other. To address this request, the Health Policy and Institutional Development (HPID) Center (a WHO Collaborating Center at the Agence de Médecine Préventive - AMP), in collaboration with WHO, organized a meeting in Veyrier-du-Lac, France, on 11 and 12 May 2016, to establish a Global NITAG Network (GNN). The meeting focused on two areas: the requirements for (a) the establishment of a global NITAG collaborative network; and (b) the global assessment/evaluation of the performance of NITAGs. 35 participants from 26 countries reviewed the proposed GNN framework documents and NITAG performance evaluation. Participants recommended that a GNN should be established, agreed on its governance, function, scope and a proposed work plan as well as setting a framework for NITAG evaluation.

Keywords: Advisory committee, Vaccine decision-making, Vaccine evaluation, Evidence-based immunization policy, Global network on immunization, Immunization, National Immunization Technical Advisory Group, NITAG, Vaccine

Abbreviations: AMP, Agence de Médecine Préventive; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; GNN, Global NITAG Network; HPID Center, Health Policy and Institutional Development Center; NITAG, National Immunization Technical Advisory Group; NRC, NITAG Resource Center; SIVAC, Supporting Independent Immunization and Vaccine Advisory Committees

1. Introduction

The Global Vaccine Action Plan states as Strategic Objective 1 that “All countries commit to immunization as a priority” [1]. In support of this, National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs) provide independent, evidence-informed advise on the entire range of vaccines suited to the population across the age range that can assist the government’s immunization policy formation [2]. The contributions of NITAGs are now well recognized and valued by high-income countries and at the global level. However, in some low- and middle-income, NITAGs are still lacking or face significant challenges [3], [4], [5]. The Health Policy and Institutional Development Unit (HPID) of the Agence de Médecine Préventive (AMP) is a World Health Organization Collaborating Center on evidence-informed immunization policy-making that was tasked in 2008 with supporting the establishment and strengthening of NITAGs in low-income countries, the Supporting Immunization and Vaccine Advisory Committees (SIVAC) Initiative [6]. At the request of many countries, the NITAG Resource Center (NRC) was revamped by HPID in 2015 to serve as a platform for exchanges across NITAGs [7], [8], [9]. While this is seen as a useful tool and a positive step forward, many NITAGs called for the establishment of a network of NITAGs to allow experiences and lessons learned to be more readily shared and discussed; i.e., to go beyond the sharing of documents on the NRC.

In order to address this request, the AMP-HPID Center organized, in collaboration with WHO, a meeting in Veyrier-du-Lac, France, the 11 and 12 May 2016, to establish a Global NITAG Network (GNN). This meeting focused on two areas: the requirements for (a) the establishment of a global NITAG Collaborative Network; and (b) the global assessment/evaluation of NITAG performance.

To facilitate discussion and make the meeting more manageable from a logistics and cost perspective, the number of countries invited was limited. Countries were selected based on several criteria the functionality of their NITAG, income, geographic location, regional influence, and eligibility for SIVAC support. The invitations were sent to the NITAG Chair or country via email, either directly or through the WHO regional office. Most of the countries were interested in attending. Invitations were sent to 46 countries; 26 were able to attend with 18 of these sponsored by AMP-HPID and WHO. The remaining eight attending countries self-funded. Amongst the 20 invited countries not attending, the main reasons given were lack of funding/sponsorship, calendar conflicts with country internal program meetings, administrative obstacles and/or visa and last minute plane complications. Countries with NITAGs were represented by their NITAG Chair and/or Secretariats, and countries without a formal NITAG (three in total) sent the relevant staff as designated by their Ministry of Health. Appendix A lists participants by countries as well as representatives from the organizing, partner and donor institutions that attended.

In advance of the meeting, the AMP-HPID Center circulated a draft document that provided an overview of the proposed principles, functions, roles and governance of a GNN to serve as a template for discussion. Similarly, a tool for assessing and evaluating a NITAG’s performance was developed and circulated in advance to participants. We report here on the outcome and recommendations from this workshop as well as the results of a participant questionnaire about the proposed GNN and NITAG evaluation.

2. Materials and methods

Presentations from the meeting have been made available at the NITAG Resource center <http://www.nitag-resource.org/fr/mediatheque/resultats-de-recherche?document_type=54&topic=37&disease=&geographical_area=&sort=recent&offset=0>.

2.1. Day 1: GNN establishment

Plenary sessions: The meeting began with a discussion of the proposed GNN principles, roles, management and governance. Presenters from WHO and other partner institutions gave an overview of global recommendations on NITAGs and the challenges in meeting these. This was followed by presentations on the budding regional NITAG networks in Europe and in South-East Asia including their mandates and other perspectives. The plenary session concluded with an overview of the NRC, the online platform that could serve as a backbone for such networks.

Small group discussions: Country representatives then gathered in breakout sessions with balanced groups of 10 and 11 persons to discuss the pre-circulated draft GNN strategic document. They suggested revisions to the GNN’s format, mandate, roles, governance and discussed funding risks and opportunities.

GNN Survey: Participants were then surveyed to assess their perceptions about a global network, their level of interest and the desired outcome. Participants were asked to rate the importance of a global network for their own country’s NITAG and globally for NITAGs on a four items Liekert scale [10]: Extremely important; quite important; fairly important; not important at all.

2.2. Day 2: NITAG evaluation

Plenary sessions: The second day started with a presentation on the NITAG evaluation tool developed by AMP-HPID and partners, followed by presentations from countries on their NITAG evaluation experiences and by plenary discussions.

Small group discussions: Participants then met in breakout groups to discuss their NITAG requirements for performance evaluation and the possible forms of support expected from the GNN and partners in this regard.

Participants from donor and technical partner organizations were briefed beforehand so that they could facilitate, guide and help summarize the breakout group’ discussions during the plenary.

3. Results: Observations and recommendations from the meeting

3.1. Global NITAG network establishment

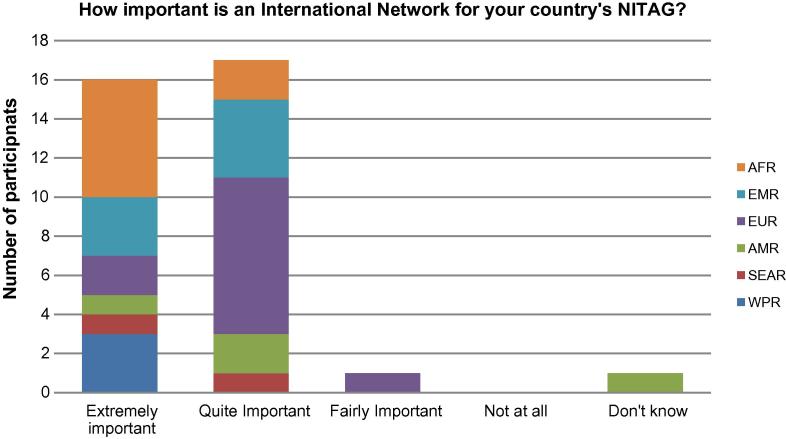

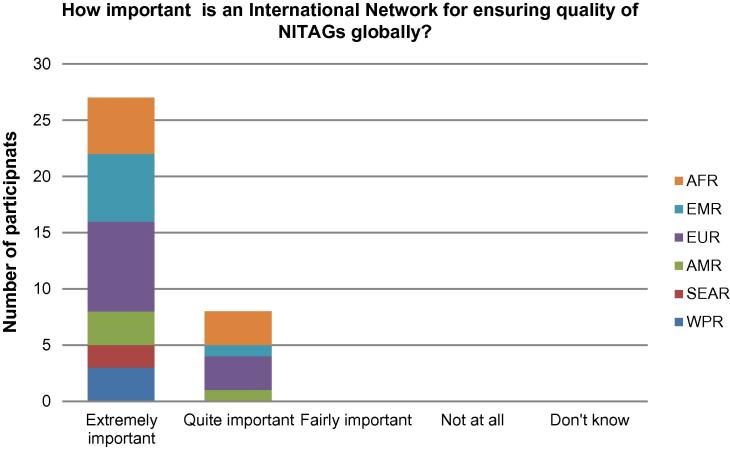

As shown in Fig. 1, participants considered the establishment of a GNN of high importance for their own NITAG. 16/35 participants (45.7%) rated it as “extremely important” and 17/35 (48.5%) as “quite important”. With respect to the importance of the GNN for ensuring quality of NITAGs globally, as shown in Fig.2, 28/35 participants (80%) rated it as “extremely important”.

Fig. 1.

Responses by individual meeting participants on importance of a NITAG network for their individual country’s NITAG.

Fig. 2.

Responses by individual meeting participants on the importance of an international NITAG network for ensuring quality of NITAGs globally.

After reviewing the draft document on the establishment of a GNN, participants highlighted a number of key points.

3.1.1. Background and rationale

NITAGs are currently not well connected and many face challenges that inter-NITAG relationships might help to address e.g. a lack of expertise and capacity building needs. A GNN can facilitate such relationships, but there would need to be a clear rationale, vision and mission as well as a coordinating body if the GNN is to be accepted and function well. For NITAG participation to be maximized, joining the GNN must not increase the burden on individual countries' NITAGs and must facilitate and support NITAGs but not drive their national agendas. Contributions must be voluntary and made in accordance with each country’s abilities and permissions. The GNN would also work more smoothly if roles and interactions between the GNN and the regional NITAG networks, where they exist, are clarified in advance so that the GNN does not duplicate or act as a replacement for a country NITAG nor limit the value of regional networks.

3.1.2. Values and principles

Every NITAG has something valuable to share. Membership in the GNN should be free of charge and voluntary, as should be collaboration and sharing of information. Inter-relationships between NITAGs must not be forced or prescriptive. Each country alone must decide on the confidentiality of their various NITAG-related documents i.e. which can and cannot be shared. The GNN must accept that there are different levels of confidentiality of documents to be shared across NITAGs. Active exchange of information encouraged by the GNN Secretariat (see below) rather than current simple passive sending of files through the NRC is recommended. Capacity-building activities are also needed. These could potentially be more efficient and effective if thought about at a global rather than regional or local level. Participants highlighted the value of interactions with their direct geographic neighbors, as well as the importance of opportunities to learn from NITAGs in similar economic settings or from those speaking the same language(s).

3.1.3. Governance and coordination

A Board of a reasonable size with both a steering and an advisory role is required to lead the activities of the GNN. The Board’s ideal composition was not determined but participants suggested that it could be composed of NITAG representatives with a regular rotation of membership. Criteria could be set to guide the choice of countries, the inclusion of representatives from regional networks as well as the rotation time. Straightforward guidelines are also needed to inform the setting of the GNN’s priorities and agenda items. These tasks would be coordinated and managed by the GNN Secretariat. The majority of participants suggested that the HPID Center at AMP may serve as the GNN Secretariat considering its role as a WHO CC.

The roles of the GNN’s Board would involve strategic direction setting, increasing the GNN’s visibility as well as fundraising for the GNN’s functioning and activities.

The need to raise funds for the GNN was considered essential. The South East Asia NITAG funding model, in which countries fund their own participation in Network meetings and the host country chairs the meeting and facilitates the logistics, was not seen as viable for all countries. Participants emphasized that mobilizing resources needs to (a) reflect the governing principles of the GNN and (b) should not be charged per country. Strategies for funding and securing support for the GNN is expected to be a major initial focus for the GNN Board and Secretariat.

3.1.4. GNN assessment

The participants agreed that it would be critical to monitor and evaluate the GNN in a regular and practical way. A baseline needs-assessment should be conducted so that the true impact can be measured later. For example, the way the GNN work plan items fit in with, and respond to the needs of individual countries is crucial. A few methods were proposed to systematically assess functioning and ensure usefulness of the GNN, such as the measurement of time and cost-savings for member NITAGs, satisfaction surveys, recognition of contributions and a collection of examples of how countries have helped each other on specific topics. These measurements could also help with external reporting to outside funders and supporting institutions. The GNN assessment outcomes would also be reviewed and monitored by a steering committee and shared across the member countries.

3.2. NITAG evaluations

The second day of the meeting was dedicated to the critical topic of NITAG evaluations. Indicators previously used in NITAG evaluations assessed their operations, or their processes, outputs and outcomes. However, while useful [11], a more fulsome assessment tool was still lacking, one that could guide NITAG evaluators through the planning, conduct and analysis of the evaluations. Such a tool would ensure consistency and comparability of evaluation outputs across countries. To address this gap, and based on the lessons learned from previous evaluation experiences led by AMP-HPID in Mongolia, Nepal, Uganda and Ivory Coast and from partners [12], a NITAG evaluation tool [13] developed by the AMP- HPID Center, was revised by WHO partners and the US-CDC before circulation pre meeting to the participants. This evaluation tool uses a multi-dimensional approach looking specifically at three NITAG dimensions: NITAG functioning, the quality of its recommendations, and its integration into the national immunization decision-making processes. The tool includes a detailed questionnaire to review each aspect within these dimensions. It comprises guidance on (a) how to plan for a NITAG evaluation (defining a scope, a perspective, a plan of analysis, etc.); (b) how to adapt the questionnaire to the country's context; and (c) how to analyze results and make recommendations. This tool has been used to evaluate NITAGs in Armenia and Moldova in 2016 [14]. The NITAG evaluation tool was designed for use by external evaluators, but could also be used for self-evaluation.

The meeting discussion on the need for a more comprehensive and standardized NITAG evaluation highlighted many advantages and benefits, not just for the purposes of accountability globally but also for their potential use in advocacy and communications at country level. Participants noted that results and recommendations from sequential NITAG evaluations could be used to demonstrate the added value of NITAGs to decision-makers. It was acknowledged that some countries might not permit sharing or publishing of the their country’s evaluation but countries could still provide feedback on the tool itself through the GNN Secretariat. The NITAG evaluation tool could also help an individual country's NITAG to compare itself with NITAGs in other similar or different countries.

Two main themes emerged from the discussion on NITAG evaluations: firstly, the need to form a pool of trained evaluators and, secondly, the need to raise awareness of the benefits of NITAG evaluations, at a minimum to the NITAG Chairperson, Secretariats and members. The Network could facilitate the training of trainers. A guide for evaluators or a short introduction module would be helpful to facilitate the use of the tool. It was noted that it may be of more value for the evaluation to be conducted by an individual who is familiar with the way the NITAG functions rather than an expert in evaluations as the NITAG tool itself guides the evaluator through each of the steps of the evaluation. The more critical aspect of the evaluation rests in the interpretation of the findings, and for this an understanding and knowledge of NITAG work and functioning is crucial. Twenty-two participants agreed to be included in the pool of trainers who will help NITAGs to conduct their evaluation.

Participants agreed on the value of systematically evaluating their NITAG using the tool presented. Furthermore, they were committed to sharing the results of the evaluations. Participants suggested that, although an independent evaluation is important, countries should be encouraged to conduct an initial self-assessment (if possible) to adjust their functioning prior to external evaluation. They could subsequently request support from partners for external evaluation if needed. Partners can provide technical assistance but countries should favor local solutions as much as possible to reduce costs. Other “local” solutions could include working with neighboring countries to provide low-cost assistance.

Participants agreed to provide feedback and/or share results on the NITAG evaluation tool, either by email immediately after the meeting or once they have used it internally. A template will need to be developed to facilitate and systematize feedback from countries.

Overall, the assembly recommended that NITAGs should:

-

–

Consider the relevance of conducting a self-evaluation before engaging in a larger external evaluation.

-

–

Share their evaluation results (via the NRC).

-

–

Document the implementation of their evaluation and the follow-up on the recommendations and engage in peer-to-peer support for evaluation.

-

–

Get support from the GNN for their evaluation via a pool of trained evaluators.

-

–

Rely on materials developed by the Network Secretariat, to familiarize and train NITAGs in the evaluation process.

3.3. Next steps

The meeting participants agreed that a core group to steer the next steps will be selected from the countries that volunteered during the meeting, including: Albania, Argentina, Australia, Canada, Costa Rica, Indonesia, Mozambique, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, the Sudan, the United Kingdom, and Uganda. The length of term for these initial GNN core group countries will need to be staggered, represent diversity e.g. including amongst developing countries and also support links to regional NITAGs.

Participants strongly recommended that each participant try to ensure that their country send a representative to the GNN meeting on an annual basis and that the meeting be organized by AMP-HPID. Suggested workshop themes for upcoming meetings included methods on: reviews, decision-making, specific evidence-grading methodologies such as the “Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE)” [15], economic analysis and a review of the resources and training required to do this work.

4. Discussion

This global workshop led to constructive discussions on the establishment of a GNN linking NITAGs around the world. The GNN would provide the opportunity for each country and the institutional partners to share views and challenges on NITAG work. Countries attending the meeting were keen to form the GNN. The meeting highlighted the value to countries of sharing their experiences and lessons learned in conducting NITAG work. Participants emphasized the value of having such an opportunity to learn from each other and to be officially linked within a network, with the NRC as a platform. For the GNN to work well, it needs to meet on a regular basis. Using a GNN to facilitate NITAG evaluation was also an area of high interest to all the countries attending. Despite the possibility that confidentiality rules may preclude the sharing of some information, overall country NITAG representatives felt that NITAGs should be encouraged to share evaluation results and feedback via the NRC to support future evaluations. Additional suggestions were made during the meeting on how to move forward with the GNN evaluation program such as the potential for joint NITAG evaluations with EPI review programs.

Discussions also highlighted the difficulty of funding future GNN activities, including country-specific research and training programs, operations support, IT solutions, translation of documents and materials and meeting costs. The fear that money from funding agencies, partners and high-income countries might create a conflict of interest with respect to agenda and priority setting was seen as a challenge to the GNN fundraising team. This might be mitigated with a strong management of conflict of interest policy for the GNN.

WHO and other partners noted that the global framework of the Sustainable Development Goals and Universal Health Coverage is an overarching environment that supports this GNN initiative. While only about half of the world’s currently in place NITAGs were invited to attend this meeting and funding was provided for a very limited number, the breadth of attendance in terms of WHO regions and country income levels was very encouraging. As other country NITAGs learn of the GNN, it is expected that membership will expand. As the GNN develops, it will enable information and evidence to be leveraged not only at country level but also on a collaborative platform and around the globe.

Funding and conflict of interest statements

The meeting was organized by the Health Policy and Institutional Development (HPID) Center, a WHO Collaborating Center, which is part of a separate legal entity within AMP that receives no support from vaccine manufacturers. The meeting was funded by a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. No conflicts of interest are declared.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank WHO colleagues, Isabelle Wachsmuth and Kamel Senouci, who kindly provided technical advice during the preparation of meeting materials and to Andrée Diakité of AMP, who provided logistical support to participants attending the meeting. Our particular thanks to all invitees who expressed an interest in attending but were not able to obtain funding for their trip and/or get a visa.

Appendix A. First GNN meeting participants

Country participants

Albania: Iria Preza and Eduard Kakarriqi; Argentina: Pablo Bonvehi and Daniel Stecher; Australia: Madeleine Hall; Burkina Faso: Rasmata Ouedraogo; Canada: Robert Lerch; Costa Rica: Roberto Arroba; Côte d’Ivoire: Vroh Joseph Benie Bi and Emmanuel Bissagnene; Egypt: Hamed El-Khayat and Mohamed Genedy; France: Daniel Levy-Bruhl; Indonesia: Toto Wisnu Hendrarto; Malawi: Macpherson Mallewa; Moldova: Victoria Bucov and Tiberiu Holban; Mozambique: Jahit Sacarlal; Nepal: Rajendra Prasat Pant and Rupa Sing Rajbhandari; Netherlands: Hanneke Dominicus; Panama: Xiomara de Mendieta; Philippines: Gerardo Bayugo; Portugal: Teresa Fernandes and Graça Freitas; Saudi Arabia: Aisha Alshammary and Ibrahim Zaid Bin Hussain; Senegal: Anta Tal Dia; Sudan: Zainelabdein Karrar; Sweden: Adam Roth; Tunisia: Souad Bousnina; Uganda: Celia Nalwada and Nelson Sewankambo; United Kingdom: Andrew Earnshaw and Anthony Harnden; Vietnam: Nguyen Xuan Tung.

Participants from organizing institution

AMP-HPID center: Alex Adjagba; Bruna Alves de Rezende; Antoinette Ba-Nguz; Laura Davison; Antoine Durupt; Louise Henaff; Inmaculada Ortega Perez; Chloé Thion; AMP-HPID interns: Sara Bahnini and Bridget Relyea; Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada: Noni E MacDonald.

Participants from technical partner institutions

AMP: Alfred da Silva; WHO HQ: Kaushik Banerjee; Philippe Duclos; Melanie Marti; Kamel Senouci; Isabelle Wachsmuth; WHO African region: Blanche-Philomène Melanga Anya.

WHO Eastern Mediterranean region: Mustapha Ramadan (consultant); WHO European region: Liudmila Mosina; WHO American region: Cara Janusz; WHO Western Pacific Region: Laura Davison (AMP staff posted in WHO WPRO); US-AID HQ: Endale Beyene; US-CDC: Kathy Cavallaro and Abigail Sheffer.

References

- 1.Strategic advisory group of experts on immunization-who. global vaccine action plan. <http://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/GVAP_Strategic_Objective_1-6.pdf?ua=1> [10 December 2016, date last accessed].

- 2.Duclos P., Dumolard L., Abeysinghe N., Adjagba A., Janusz C.B., Mihigo R. Progress in the establishment and strengthening of national immunization technical advisory groups: analysis from the 2013 WHO /UNICEF joint reporting form, data for 2012. Vaccine. 2013;31:5314–5320. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.HPID Center-NITAG Resource center. SIVAC initiative. <http://www.nitag-resource.org/who-we-are> [accessed 15 March 2017].

- 4.Adjagba A., Senouci K., Biellik R., Batmunkh N., Faye P.C., Durupt A. Supporting countries in establishing and strengthening NITAGs: lessons learned from 5 years of the SIVAC initiative. Vaccine. 2015;33(5):588–595. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ba-Nguz A., Adjagba A., Wisnu Hendrarto T., Sewankambo N.K., Nalwadda C., Kisakye A. The role of national immunization advisory groups (NITAGs) in the introduction of injectable polio vaccine (IPV) for the polio endgame strategy. J Infect Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw601. Accepted for publication December. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senouci K., Blau J., Nyambat B., Coumba Faye P., Gautier L., Da Silva A. The supporting independent immunization and vaccine advisory committees (sivac) initiative: a country-driven, multi-partner program to support evidence-based decision making. Vaccine. 2010;28:A26–A30. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nijsten D., Houweling H., Durupt A., Adjagba A. Overlapping topics in advisory reports issued by five well-established european national immunization technical advisory Groups from 2011 to 2014. Vaccine. 2016;34:6200–6208. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perronne C., Adjagba A., Duclos P., Floret D., Houweling H., Le Goaster C. Implementing efficient and sustainable collaboration between national immunization technical advisory groups: report on the 3rd international technical meeting, Paris, France 8–9 December, 2014. Vaccine. 2016;34(11):1325–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adjagba A., Henaff L., Duclos P. The NITAG Resource Center (NRC): one-stop shop towards a collaborative platform. Vaccine. 2015;36:4365–4367. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Pshycology. 1932;22:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blau J., Sadr-Azodi N., Clementz M., Abeysinghe N., Cakmak N., Duclos P. Indicators to assess National immunization technical advisory groups (NITAGs) Vaccine. 2013;31:2653–2657. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.HPID Center-NITAG Resource center. ivory coast NITAG evaluation. <http://www.nitag-resource.org/media-center/document/3426-evaluation-du-gtcv-de-la-cote-d-ivoire-cneiv-ci> [accessed March 15, 2017].

- 13.HPID Center-NITAG resource center. evaluation tool. <http://www.nitag-resource.org/media-center/document/1517-evaluation-tool-for-national-immunization-technical-advisory-groups-nitags> [accessed March 15, 2017].

- 14.HPID Center-NITAG resource center. armenian NITAG evaluation. <http://www.nitag-resource.org/media-center/document/3424-armenian-nitag-evaluation> [accessed March 15, 2017].

- 15.The GRADE working group. <http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org> [accessed March 15, 2017].