Abstract

The present paper examines the current status of women-centered substance use disorder treatment in Georgia. Four major issues are identified that adversely impact the delivery of effective services for women with substance use disorders: Policy Issues; Sociocultural Issues; Programmatic/Structural Issues; and Personal/Interpersonal Issues. These four issues are seen to form a complex, dynamic system that serves to maintain the current ineffective service delivery system and suppresses movement toward an effective service delivery for this highly marginalized and at-risk population. How these issues, and their interplay, present continuing barriers to the development and implementation of effective treatment for this population are outlined and discussed. In order to overcome these barriers, solutions must be sought in four areas: Policy reform; Public health campaigns; Development and implementation of comprehensive women-specific confidential treatment models; and Empowering women. Specific goals in each of these areas that would achieve a positive impact on various aspects of the functioning of the current service delivery system for women with substance use disorders are suggested. Simultaneously seeking solutions in all four of these areas would improve the service delivery system and benefits women with substance use disorders.

Keywords: women, substance use treatment, policy

Introduction

In sharp contrast to data available from Europe and the United States (CADAP, 2012; EMCDDA, 2005; Grella, 2007), women comprise only 2% of the known patient population in treatment for substance use disorders in Georgia (Javakhishvili, Sturua, Otiashvili, Kirtadze, & Zabransky, 2011) and 64% of Georgian women with substance use problems have no information about treatment services in their geographical area (International Harm Reduction Development Program, 2009). Moreover, there are no reliable estimates of the prevalence of females with either problem substance use or dependence (Sirbiladze, 2010). Little empirical research has been conducted examining patterns of substance use or lifetime trajectories of substance use in Georgian women.

The few fragmented attempts to address substance use disorders in women have stemmed from pilot women-centered HIV prevention services in Gori and Zugdidi (regional centers in west Georgia). These efforts have provided useful information on the outreach and engagement strategies that might prove effective in meeting the needs of this population within the local context. Despite these limited efforts, women in Georgia with substance use disorders remain one of the single most underserved populations of marginalized and disadvantaged women (Kirtadze et al., 2013a).

Several recent studies that have attempted to describe the environment in which substance use by women in Georgia is initiated and sustained, and to identify factors influencing substance use trajectory and treatment-seeking behavior of women (Kirtadze et al., 2013b; D. Otiashvili et al., 2013). This research has suggested that poor self-concept combined with severe social stigma, absence of comprehensive women-focused treatment programs, and often hostile and judgmental attitudes of health service providers, all play critical roles in creating barriers to both general health and substance-use-related services for women with substance use problems. A Georgian culture that has a gender power imbalance based on male dominance (Chitashvili, Javakhishvili, Arutiunov, Tsuladze, & Chachanidze, 2010; Nizharadze, Stvilia, & Todadze, 2005), and stigmatization from Georgian culture at large – as well as specifically from substance-using males – further contribute to the elevated risks for injection use and sexual transmission of HIV in substance-using women. Women with substance use disorders are likely to inject with more partners, inject with syringes used by male partners, and engage in sexual relationships in exchange for illicit substances or money (Curatio International Foundation & Public Union Bemoni, 2009; Kirtadze, et al., 2013a). In addition, both harsh drug laws and criminalization of substance use are known to more seriously impact substance-using women than substance-using men. Taken together, this nexus of activities describes a complex set of cultural, socio-economic, programmatic, and policy issues that impact on access to treatment and willingness of women to seek health-related services, including but not limited to treatment for substance use disorders (Kirtadze, et al., 2013b; D. Otiashvili, et al., 2013).

Methods

This paper has two objectives. The first objective is to integrate the previous research on substance use disorders in Georgian women in order to provide a working model of the issues and barriers in the treatment system that impact treatment implementation, access, entry, and effectiveness for this population. The second objective is to outline how best to develop policies and practices that would lead to effective and efficient comprehensive women-centered treatment programs for women with substance use disorders in Georgia.

For the purpose of this review there were no primary data that were collected that served as the basis of the review. We conducted a review of two relevant literatures: the empirical literature on substance use disorders and their treatment in Georgia, that includes our own research on women with substance use disorders as well as the research of Georgian colleagues; and, the literature on substance use and public policy. In addition we also performed a desk review of Georgian governmental and policy documentsrelevant to the topic of our research.

Results

Working Model of the Issues and Barriers in the Treatment System

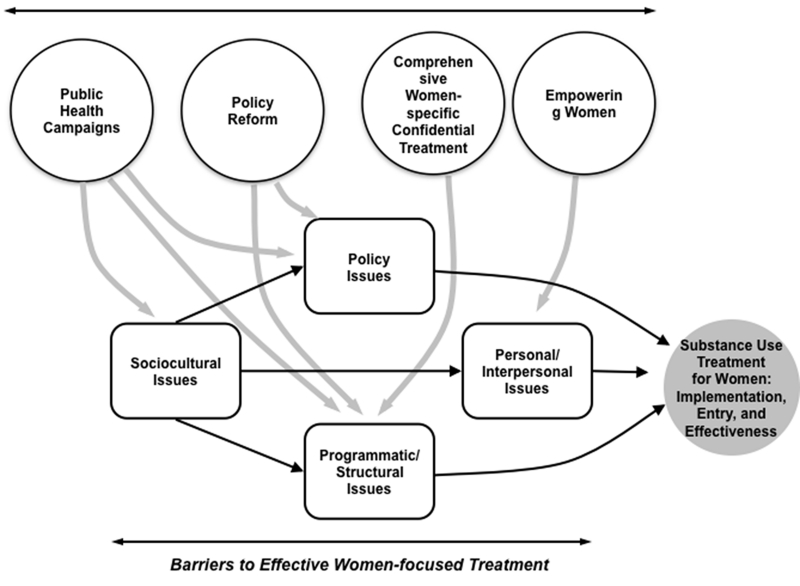

The working model of the issues and barriers in the treatment system in Georgia and their solutions can be found in Figure 1. The issues and barriers can be found in the lower portion of Figure 1. The double-headed arrow is intended to represent the fact that a woman seeking treatment for a substance use disorder in Georgia interacts with the substance abuse treatment system. The treatment system impacts the woman at the same time that the woman impacts the system. The system itself has four ongoing issues that adversely impact treatment effectiveness, and they interact with each other in a dynamic fashion, with the issues reverberating through the system. Solutions to these ongoing issues must be sought from inside and outside the system, and are depicted in the upper portion of Figure 1. These solutions occur at multiple levels (e.g., governmental, individual) and each such solution can be seen to impact some but not all issues that exist in the treatment system. Thus, to effect significant and lasting change in the system, solutions must be sought at all levels.

Figure 1. Solutions for Effective Service Delivery for Women with Substance Use Disorders.

The goal in offering this figure is to present a schematic that is useful in describing critical facets both inside and outside the treatment system that adversely impact treatment for women with substance use disorders, and to serve as a stimulus for future research. It should not be seen as providing a model based on available empirical research, as there are insufficient data in this regard. Rather, it should be considered a working model subject to both revision and expansion.

Table 1 details the critical sociocultural, policy, programmatic/structural, and personal/interpersonal barriers and issues whose interplay adversely impacts the treatment of women for substance use disorders. These barriers and issues have been reported and discussed in our previous publications (Kirtadze, et al., 2013a, 2013b; D. Otiashvili, et al., 2013). The following section highlights three additional forces not detailed in our previous research (Kirtadze, et al., 2013a, 2013b; D. Otiashvili, et al., 2013) that are acting to maintain the status quo for treatment services and treatment service delivery for women with substance use disorders in Georgia.

Table 1. Issues that Present Barriers to the Development of Effective Treatment for Women with Substance Use Disorders.

| Policy Issues | Sociocultural Issues | Programmatic/Structural Issues | Personal/Interpersonal Issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legislation: Criminalization and imprisonment |

Women who use drugs encounter stigma and discrimination from their culture, society, family and social networks |

Lack of women-specific substance use disorder treatment services |

Fear of disclosure of substance use |

| No guarantee of confidentiality and anonymity |

Denial that women can be mothers, wives, and use substances |

Absence of quality assurance of treatment system in Georgia |

Fear of stigma, discrimination, abandonment, violence |

| Insufficient government funding of comprehensive women-specific services |

Social norms and expectations | Cost of treatment | Guilt and shame |

| Intolerance | Hostile and judgmental service delivery environment |

Lack of knowledge regarding and prejudice towards substance use disorder treatment Lack of funds to pay for treatment |

Current Status of the Problem from a Public Policy Perspective

This section attempts to articulate how barriers that impede effective policy-making actually operate, and how policy-making may unintentionally or intentionally maintain current policies and programs. It also presents how to stimulate relevant organizations and individuals to develop policies that would lead to effective and efficient comprehensive treatment programs for women with substance use disorders in Georgia. The problems related to treatment access for substance-using women are examined within the context of systemic challenges that the field of service delivery for substance use disorders for adult men and women are facing. It would be an unavailing exercise to analyze barriers to the establishment of comprehensive women-centered treatment for substance use disorders without understanding the policy environment and often contradictory institutional roles and interests that ultimately shape the development of a broader response to the problem of substance use in Georgia.

Police Response to Substance Use

The Ministry of Internal Affairs (MOIA) has historically been a major stakeholder in the field of illicit drug trade and consumption. Rather than focusing on the police’s involvement with controlling drug trafficking and fighting organized drug markets, in this section of the paper we emphasize their role in targeting individuals who use illicit substances in what has been promoted as a “measure to reduce drug-related demand through preventive effect of punishment”. In response to the evident drug use epidemic in the mid-2000s, Georgia introduced a zero tolerance policy – strict administrative and criminal sanctions were put in place and law enforcement agencies were ordered to implement what can be described as a “Georgian drug war”. A dramatic increase in police activity aimed at identifying individuals who use illicit substances through massive street drug testing [an exercise that has been labeled as “random street drug testing” (D. Otiashvili, Kirtadze, Tsertsvadze, Chavchanidze, & Zabransky, 2012; D. Otiashvili, Sárosi, & Somogyi, 2008)] has resulted in tens of thousands of Georgian citizens and visitors to the country forced to undergo urine drug screening following a police officer’s “reasonable doubt” (defined by the Code of Criminal Procedure of Georgia as a doubt that allows objectively and with high probability to assume that individual had committed unlawful action). For example, in 2007 in an unprecedented move on the part of Georgian police forces, about 5% of Georgia’s male population ages 15-64 were forced to undergo testing for illicit substances (D. Otiashvili, et al., 2008). It is not medical personnel, or a social service agency worker, or a low-threshold program outreach worker who represents the primary contact points for people with substance-use-related problems. Rather, it is a person in police uniform who has been given the prime mandate to solve the country’s drug problem. Thus, the vast majority of initial contacts that individuals suspected of drug consumption have with any state or non-governmental institution in Georgia is with a member of the police force. In 2011 about 6,500 adults who used illicit substances received any kind of substance use treatment and HIV prevention services, in sharp contrast to more than 27,000 episodes of police-instigated drug testing that were registered that year (Javakhishvili et al., 2012). Notably, legislation and police practices do not provide options for applying measures alternative to punishment and no legal or administrative mechanism exists that would allow police to refer individuals in need of assistance to the services from which they might benefit.

Funding for Treatment for Substance Use Disorders

Funding of substance-use-related services has remained a major issue affecting the availability and accessibility of treatment for substance-use-related disorders for both women and men. A significant part of services provision, in particular, low-threshold harm reduction services, relies solely on international funding. Given the recent restructuring of the Global Fund’s funding model (AIDSPAN, 2011) and Georgia’s improving economic indicators (lower-middle income economy with low burden of disease) the country faces the challenge of losing this single major source of funding for HIV prevention within the near future. Although national health expenditures have been increasing since 2001 in monetary terms (Chanturidze T., Ugulava T., Dura’n A., Ensor T., & Richardson E., 2009) access to health care, including to substance use treatment, is limited to a large extent by an individual’s ability to pay rather than an entitlement program that allows access to different pre-paid services. This practice severely affects access to treatment for women with substance use disorders because in most of the cases they are financially dependent on family of origin and/or on their male partner, who very often also has a substance use disorder, and is not supportive of his partner seeking such treatment (Kirtadze, et al., 2013b; D. Otiashvili, et al., 2013). Importantly, neither state-funded insurance nor private insurance programs cover screening, assessment, or treatment for substance-use-related problems for either women or men.

Although funding for treatment of substance use disorders in Georgia has been increasing in recent years, reaching $US 2,000,000 in 2012 (Javakhishvili, et al., 2012), it still remains highly inadequate to the needs identified. It is estimated that public expenditures on substance demand reduction was approximately 38€ per adult with problem substance use in 2013 (Government of Georgia, 2012). This amount is extremely low compared to average European expenditures of about 2,000€ per adult with problem substance use (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2004). Given this lack of funding, it is not surprising that substance use treatment and harm reduction programs altogether are able to deliver services to only 5-10% of adults with problem substance use in Georgia (Javakhishvili, et al., 2012). Importantly, neither state-funded treatment programs, nor programs supported by international donors focus on a provision of gender-specific services. Countrywide, there is not a single treatment facility that offers comprehensive women-centered treatment for women with substance use disorders.

Options for raising additional funds to support treatment for substance use disorders have long been discussed among policy-makers and the professional community. Among other strategies, it was proposed to increase (already high) administrative fines for substance use and re-direct this money to treatment programs for individuals with substance use disorders. Unfortunately, this idea found support among a number of providers of clinical services, which raises obvious ethical questions because such a policy would undermine the fundamental trust that treatment beneficiaries would need to have in services provided by the “caregivers who first want to force you to pay a fine, have the state take your money and pay their clinics, and then do good for you”.

Continuous reliance on financial assistance from external agencies and dependence on ‘easy’ solutions (such as the “pay fine-be treated” option) reflect both the lack of political will on the part of policy-makers, along with the resistance of health care providers to engage in direct political advocacy. Too often, political leaders are unwilling to engage in activities that would call into question their position of being ‘hard on drugs’, and/or provide reasons for critics to blame them for wasting ever-scarce public resources on helping “junkies who should be solely responsible for their problems”. Service providers, in their turn, are sensitive about their relationships with decision-making institutions and want to ensure they are guaranteed at least the level of funding at which they are currently funded. Therefore, in many cases they avoid taking a position that might be seen as too critical of the current service delivery models and therefore tend to espouse a position that would create the least problems for administrators in relevant government offices.

Inertia in the Treatment System

While drug legislation and lack of funding have been identified as major legislative issues impeding development of effective treatment for substance use disorders, the treatment system in turn has long suffered from a lack of leadership and lack of commitment to implement major reforms. Current substance use service delivery models in Georgia are functioning in the absence of both quality standards for treatment and clinical protocols. There are no commonly-agreed-upon indicators to measure treatment success, and clinicians in both substance-free medication-assisted withdrawal and agonist maintenance programs rely on individual perceived outcome measures in assessing effectiveness of programs they are implementing (Kirtadze, Menon, Beardsley, & Forsythe, 2012; Kirtadze, et al., 2013b). In addition, the Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Affairs (MOLHSA) has abandoned a system of continuing education for the health care professions since early 2008. Therefore, health care personnel have few opportunities and little incentive to advance their professional qualifications and seek current knowledge and new skills. This situation has resulted in treatment systems in which very few providers of substance-use-related services have sufficient knowledge and skills to effectively address the needs of specific groups of patients, in particular women with substance use disorders. Moreover, both the treatment capacity and professional commitment to effectively address special needs that populations such as substance-using women might have is largely lacking. Not surprisingly, the relatively rapid expansion of medication-assisted treatment has failed to benefit women with substance use disorders. In 2011 only 1% of patients in methadone maintenance programs were females (Javakhishvili, et al., 2012). It may be necessary to provide agonist treatment more widely in order to effect change in the treatment system for substance use disorders; however, such change is unlikely to be sufficient to meet the unique needs and issues of women in need of such treatment.

Solution for Effective Service Delivery for Women with Substance Use Disorders

The upper portion of Figure 1 outlines the four areas in which it is essential that changes be undertaken in order to yield an effective treatment system that provides woman-focused treatment for substance use disorders, and how each area impacts the barriers and issues that currently exist to impede effective treatment for women with substance use disorders in Georgia. Below we outline the changes that need to be made in this interdependent system to effect change. Table 2 outlines the proposed solutions that are necessary within these four areas: Public health campaigns, policy reform, comprehensive women-focused confidential treatment, and empowering women.

Table 2. Proposed Solutions for Effective Service Delivery for Women with Substance Use Disorders.

| Policy Reform | Public Health Campaigns | Development and Implementation of Comprehensive Women-specific Confidential Treatment Models |

Empowering Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changing drug legislation (decriminalization; alternatives to imprisonment) |

Stigma and discrimination reduction campaigns |

Creation of tolerant treatment environment supportive of women’s needs and aspirations |

Education, job training, and employment assistance |

| Increasing funding for women-specific comprehensive drug use disorder treatment services |

Public health education campaigns to educate the public about addiction as a treatable disorder |

Outreach training for reaching vulnerable and stigmatized women |

Self-support groups |

| Legislative regulation and enforcement of confidentiality and anonymity |

Educate and sensitize policy-makers about women’s issues |

Educate Providers of Primary and Specialty Health Care |

Educating women about effects of substance use and treatment options and opportunities |

| Inclusion of women in policy discussion and policy-making and program development process |

Educate staff providing low threshold and drug treatment services |

Programs for families in recovery |

Policy Reforms

MOIA and its current functioning presents a striking example highlighting the need for major legal reform in regard to treatment of substance use disorders for women. MOIA is Georgia’s principal law enforcement agency – yet it continues to focus on its obligation to closely obey the letter of the law rather than to engage in a policy dialogue to critically assess the rationale and public impact of the current legislation and police and judiciary practices. Moreover, no shift in policy is feasible without major resource re-allocation towards increasing funding for treatment. Again, the role of politicians and decision-makers at all levels of government will be critical to ensure that ever-limited resources are directed to cover the most effective and cost-effective interventions for substance use disorders, and funding for treatment programs for which there is a major need. However, there are significant challenges to building an overall culture of rational evidence-driven decision-making that prioritizes careful long-term planning and impact-based programming. At present, decisions about funding for substance use treatment have been made in accord with political necessity – or, on the basis of the personal beliefs and opinions of particular government officials – rather than being informed by present research. Georgia, like other countries in the post-Soviet region, must begin to focus its decision-making based on research findings and the accumulated clinical knowledge base rather than continuing to believe that the sole way to address substance use is through punitive judicial activity.

Public Health Campaigns

A hostile social environment and the misunderstanding of substance use as a moral failing rather than a condition that has resulted from a complex interaction among biological, psychological, and social factors, necessitate public health education campaigns aimed at sensitization of the general public in the hopes of bringing about attitude change, especially as these issues relate to women. Interestingly, there have been a number of initiatives in Georgia supporting civil society efforts to raise public awareness about issues surrounding various marginalized populations and/or forms of behavior. Major international donors such as the European Commission (EC), Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GF), United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Open Society Foundation (OSF) and others, have supported activities focusing on improving rights of different groups such as individuals who use illicit substances, HIV+ individuals, and men who have sex with men. Nevertheless, the largely fragmented character of these efforts and lack of coordination and cooperation between these agencies and the general failure to launch initiatives directed towards these populations have prevented tangible results in terms of changing public opinion in favor of more tolerance of these heavily stigmatized populations. Civil society agencies and organizations will need to take a leading role in shaping the agenda and advocating for reforming public attitudes regarding substance use.

Both international and national funding agencies have to be encouraged to reconsider their priorities and include in their agendas funding for the one of the most underserved populations in need – women with substance use disorders. However, securing involvement of health care providers and other professional community representatives, and state institutions, as well as ensuring synergy between various initiatives will be of critical importance in achieving this goal. Given the severe stigmatization and intolerance of women who use substances from the Georgian society in general, as well as the known antipathy towards this population on the part of service providers, and the resulting low self-esteem and self-stigmatization so often found within this population (Kirtadze, et al., 2013a), public education and raising awareness becomes of particular importance in case of substance-using women in Georgia.

This public health campaign should begin with two goals. The first goal should be to educate the general public regarding the following: 1) substance dependence is a behavioral disorder not a moral failing; 2) substance dependence is treatable; 3) individuals who have substance use problems should be encouraged to seek treatment; and 4) being in treatment for a substance use problem is no different than being in treatment for any medical or psychological problem. The second goal should be a focus on educating health service providers, not simply about substance use and its treatment, but also regarding the specific needs and vulnerability of individuals with substance use problems, ethics, non-discriminative and non-judgmental approach, and encourage creation of caring and supportive service delivery environment. Such general efforts would likely remove important barriers preventing women from seeking substance-use-related and general health care services. In order for this public health campaign to bring about meaningful change for women in need of treatment for substance use disorders, within each of these two goals there should be a specific and well-defined emphasis on the unique problems that women with substance abuse disorders face in Georgia, and their unique treatment needs.

Comprehensive Women-focused Confidential Treatment for Substance Use Disorders

Previous research has indicated the need to develop comprehensive women-centered substance abuse treatment programs that incorporate components such as women-only groups, mental health programming, childcare, and other women-focused topics (Kirtadze, et al., 2013b; D. Otiashvili, et al., 2013). Training of professionals – addiction specialists, obstetricians and gynecologists, and primary-care providers – and networking among the members of these various professional organizations will help in determining the processes of identification and referral of women in need of such treatment. Moreover, such training would develop a knowledge base and skills among health care providers that could effectively address the specific needs of women with substance use problems. It is also the case that training and education of ‘front-line’ professionals – primary care physicians, nursing staff, and social workers – who have frequent and/or continuing contact with women in need of referral to treatment for substance use disorders may prove extremely helpful in the timely identification of a substance use problem. Substance use education and training of health care and mental health professionals represents a critical aspect of service delivery reform and requires thorough examination and discussion on the part of both the professional organizations involved and the larger community, including both policy-makers and beneficiary groups. Such a discussion lies beyond the focus of the present paper. However, Table 3 outlines basic needs in education and training for various professionals involved with health and social care delivery to women with substance use problems in Georgia, and can be considered as a useful starting point for further in-depth analysis and debate.

Table 3. Substance use disorder related training needs of health care providers in Georgia.

| Profession | Issue | Training needs |

|---|---|---|

| Primary health care workers and specialist health care providers (mental health, infectious disease, gynecologists, obstetricians, pediatricians) |

Health care providers are not properly trained to recognize substance use disorders; if they do recognize them, do not know how to address them |

Basic knowledge on substance use disorders; core knowledge of effective prevention, treatment, rehabilitation practices and strategies. Competency in screening and early identification, brief intervention, secondary prevention |

|

| ||

| Staff of addiction services (physicians, psychologists, nurses, social workers) |

Addiction service providers have no knowledge to address specific needs of women with substance use disorders |

Core knowledge and skills to identify and address gender-specific issues (childcare, violence, childhood abuse (physical, sexual, emotional), mental health, gynecology, endocrinology and other) |

In addition to these universal conditions, Georgia-specific needs have to be addressed in order to ensure service providers can provide treatment to prospective patients and that such treatment will be attractive and acceptable to women who should ultimately benefit from it. First, given the stigmatized nature of women’s substance use in Georgia and the overarching negative social environment in which the majority of women with substance use problems live, the need for effective outreach services, including peer outreach, cannot be overstated. Second, creating an empathetic treatment environment in which women are not judged and treated with care and respect will be a critical condition for making treatment for substance use disorders sought after – and efficacious.

It is obvious that the process of developing comprehensive women-centered substance abuse treatment models requires multi-sector and multi-stakeholder collaboration, in which the MOLHSA should play a leading role. However, most substance use services are provided by private (for-profit) and non-governmental (non-profit) organizations, and so involvement of civil society organizations along with the professional community is crucial. The Association of Narcologists and recently established Association of Addictologists have important roles to contribute to this process. Other professional associations will need to contribute to the development and implementation of not only the ethical standards for the treatment of women but also minimum acceptable standards for treatment – and they will have to ensure that health service organizations adhere to these standards. These organizations will need to establish collaborations with service provider facilities and conduct workshops and utilize other training venues (e.g., presentations at annual meetings of organizations of health service providers in Georgia). They also will need to work with teaching institutions in order to incorporate topics related to ethical and professional standards into the educational programs for health and social care providers.

Empowering Women

In our previous research we discussed issues related to personal and interpersonal barriers that play important roles in shaping the demand for treatment, and the willingness of women to utilize substance use related services (D. Otiashvili, et al., 2013). We have argued that in a current atmosphere of social hostility, stigmatization and self-stigmatization, and strong feelings of guilt and embarrassment on the part of women in need of treatment for substance use disorders, it is highly unlikely that such women will be willing to disclose their substance use and enter treatment, even if effective treatment options are available. Developing comprehensive women-centered treatment models should be implemented in parallel with, and should meaningfully incorporate activities and interventions aiming at women’s empowerment, raising self-esteem, allowing for the perception of dignity as both woman and person, coupled with equal opportunities for vocational success and personal fulfillment. Considering the sociocultural biases inherent in a Georgian culture that fail to support women with substance use problems, or actively suppress their achievement of personal and professional goals (Kirtadze, et al., 2013a, 2013b), particular attention has to be paid to fostering the development of life coping skills, and providing education, job training and employment assistance, as well as other social reintegration components. Self-support groups, family education, and parenting skills training all can serve as potentially effective mechanisms in order to develop and maintain healthy interpersonal relationships and support women’s network of relationships (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2009).

Conclusion

Drug policy in Georgia has long been a subject of debate among national stakeholders. It has been repeatedly argued, that despite rhetoric endorsing a balanced approach to substance use problems (Parliament of Georgia, 2007), substance-use-related legislation and law enforcement practices heavily emphasize a punitive rather than a rehabilitative approach to the problem of substance use (D. Otiashvili, et al., 2012; D. Otiashvili, et al., 2008). Results of the current analyses and previous reports identified Georgian drug legislation and judiciary practices as a principal barrier to improving access to services for people with substance-use-related problems (Kiknadze & Otiashvili, 2007; D. Otiashvili & Balanchivadze, 2008). Stigma and hostile public attitudes toward individuals who use illicit substances, the use of fines as the main deterrent for substance use, and the lack of availability of specialized treatment services – all have served as inter-related cogs in a system that maintains a currently ineffective service delivery environment and suppresses movement towards major reforms in either funding for treatment services for substance use or legal reforms that focus on substance use as a public health issue rather than a crime. This antiquated service delivery environment is particularly biased against service delivery of any kind – not only for treatment of substance use disorders but also for general health issues – for women. Therefore, achieving sustainable, forward-thinking substance use policy can only be brought about through a simultaneous, well-coordinated set of advocacy activities in multiple public and private sectors directed towards all problem areas, with a particular emphasis on the needs of women.

Approaching illicit substance use from a public health perspective is a necessary first step. Such an effort, with a goal of providing effective treatment to women with problematic substance use, should not be understood as meaning that problematic use of illicit substances is a ‘medical problem’ or a ‘medical issue’. As noted above, the development of problematic substance use is a complex interaction among biological, psychological, and social factors. Treatment of such problems will necessarily be comprehensive in nature, and will involve professionals who approach such treatment from different perspectives (e.g., psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, nurses). Certainly, any future policy debate, if it is to foster development of effective treatment for substance use disorders in women, will need to develop a broader agenda that includes psychosocial, economic, human rights, and freedom of choice perspectives on the problem.

Drug policy reform advocacy can only be successful if involvement of relevant stakeholders is a central aspect of the model for effecting change. Participation of individuals directly affected by substance use problems in the design and implementation of drug policies can bring critical emotional change and can act as a moving force for policy reform. We acknowledge the importance of involving clinicians, researchers, and academia in political advocacy. Such involvement brings unique professional perspectives into the policy-related debate and provides much-needed support to the efforts of civil society groups and other activists engaged in advocacy. And finally, to achieve major policy changes, advocacy needs to occur at both national and community levels. Importantly, there is an opportunity to work with local governments and to advocate for developing and supporting local demand reduction programs at a municipal level.

Major policy reform is being discussed by the Georgian legislature in 2013 – an Interagency Coordinating Council to Fight Drug Abuse has been established and drug-related legislative initiatives have been reviewed in Parliament. Importantly, this process has been inclusive and transparent, and has engaged all major stakeholders – policy-makers, service providers, field experts, and representatives of affected groups. The first-ever National Drug Strategy and Action Plan were approved in Fall 2013. Both Strategy and Action Plan include development and implementation of women-centered substance use treatment in the list of priorities. It is hoped that in parallel to the adoption and implementation of National Strategy and Action Plan, the newly elected government will be committed to recalibrate current drug policy practices and build a social culture and climate in which tolerance and care for individuals in need, effectiveness of substance use interventions is valued, and evidence-driven decision-making will be prioritized. And in that debate will be a continuing focus on the needs of one of the single most vulnerable and marginalized populations in Georgia – women with substance use disorders.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIDA grant R01 DA029880 (Hendrée E. Jones, PI). The authors would like to thank project IMEDI research staff who participated in data collection and study participants for their valuable time and effort.

Role of Funding Source

The IMEDI study, parent study to the present paper, was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). NIDA played no role in the: 1) study design; 2) collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; 3) writing of the report; or 4) decision to submit or where to submit the paper for publication.

References

- AIDSPAN Board Cancels Round 11 and Introduces Tough New Rules for Grant Renewals. Article 1 from GFO Issue 167 - 23 November 2011. 2011 Retrieved 13 March, 2012, from http://www.aidspan.org/index.php?issue=167&article=1.

- CADAP . Kyrgyzstan Country Overview: Drug situation 2010. The European Union’s Central Asia Drug Action Programme (CADAP); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment . Substance Abuse Treatment: Addressing the Specific Needs of Women. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanturidze T, Ugulava T, Durán A, Ensor T, Richardson E. Georgia: Health system review. Health Systems in Transition. 2009;11(8):1–116. [Google Scholar]

- Chitashvili M, Javakhishvili N, Arutiunov L, Tsuladze L, Chachanidze S. NATIONAL RESEARCH ON DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN GEORGIA. Tbilisi: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Curatio International Foundation. Public Union Bemoni . Bio-behavioral surveillance surveys among injecting drug users in Georgia (Tbilisi, Batumi, Zugdidi, Telavi, Gori, 2008 - 2009) 2009. [Google Scholar]

- EMCDDA . European Drug Situation Technical Data Sheet. 2005. Differences in patterns of drug use between women and men. [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction . Public Expenditure on Drugs in the European Union 2000-2004. EMCDDA – “Strategies and Impact Programme”. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Georgia 2013 budget of the Ministry of Labour, Health and Social Affairs of Georgia. 2012 Retrieved 7 February, 2013: http://www.moh.gov.ge/files/01_GEO/Biujrti/2013-Biujeti5.pdf.

- Grella CE. Substance abuse treatment services for women: A review of policy initiatives and recent research. Integrated Substance Abuse Programs; Los Angeles: UCLA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- International Harm Reduction Development Program . Women, Harm Reduction, and HIV: Key Findings from Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Ukraine. New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Javakhishvili DJ, Balanchivadze N, Kirtadze I, Sturua L, Otiashvili D, Zabransky T. Overview of the Drug Situation in Georgia, 2012. Global Initiative on Psychiatry/Alternative Georgia; Tbilisi: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Javakhishvili DJ, Sturua L, Otiashvili D, Kirtadze I, Zabransky T. Overview of the Drug Situaion in Georgia. Adictologie. 2011;11(1):42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kiknadze N, Otiashvili D. Georgia: anti-drug law violates human rights. HIV AIDS Policy Law Rev. 2007;12(2-3):69–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirtadze I, Menon V, Beardsley K, Forsythe S. Assessing the Costs of Medication-Assisted Treatment for HIV Prevention in Georgia. Futures Group, USAID | Health Policy Initiative Costing Task Order; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kirtadze I, Otiashvili D, O’Grady KE, Zule WA, Krupitskii EM, Wechsberg WM, et al. Drug-using Women in the Republic of Georgia: In their Own Words. 2013a. Under review. [Google Scholar]

- Kirtadze I, Otiashvili D, O’Grady KE, Zule WA, Krupitskii EM, Wechsberg WM, et al. Twice stigmatized: Health service provider’s perspectives on drug-using women in the Republic of Georgia. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2013b;45(1):1–9. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2013.763554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nizharadze G, Stvilia K, Todadze K. HIV and AIDS in Georgia: A Socio-Cultural Approach. UNESCO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Otiashvili D, Balanchivadze N. Alternative Georgia publications. Tbilisi: 2008. The system of registration and follow-up of drug users in Georgia. [Google Scholar]

- Otiashvili D, Kirtadze I, O’Grady KE, Zule WA, Krupitskii EM, Wechsberg WM, et al. Access to treatment for substance-using women in the Republic of Georgia: Socio-cultural and structural barriers. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otiashvili D, Kirtadze I, Tsertsvadze V, Chavchanidze M, Zabransky T. How Effective Is Street Drug Testing. Alternative Georgia; Tbilisi: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Otiashvili D, Sárosi P, Somogyi G. The Beckley Foundation Drug Policy Program, Briefing paper fifteen. 2008. Drug control in Georgia:drug testing and the reduction of drug use? [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of Georgia . Approval of Principal Directions of Georgia’s National Anti-Drug Strategy. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sirbiladze T. Estimating the prevalence of injection drug use in Georgia: Concensus report. Bemoni Public Union; Tbilisi: 2010. [Google Scholar]