Abstract

A complex spectrum of mixed brain pathologies is common in older people. This clinical pathologic conference case study illustrates the challenges of formulating clinicopathologic correlations in late-onset neurodegenerative diseases featuring cognitive-behavioral syndromes with underlying multiple proteinopathy. Studies on the co-existence and interactions of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) with neurodegenerative non-AD pathologies in the aging brain are needed to understand the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration and to support the development of diagnostic biomarkers and therapies.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, corticobasal syndrome, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, multiple proteinopathy, neuropathology

Introduction

Current notions about direct clinicopathologic correlations in neurodegenerative disorders have been recently challenged by observations of frequent co-occurrence of pathologies in the aging brain. The association between the pathological features of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common degenerative neurocognitive disorder, and dementia, is known to attenuate in the oldest old (Savva et al., 2009). At the same time, pathological studies have shown a concomitant age-dependent increase in the prevalence of non-AD pathologies in which presence is independently associated with cognitive decline (Wilson et al., 2013). A complex convergence of neuropathologies featuring protein aggregation is also fairly prevalent in cognitively normal adults (Sonnen et al., 2011) and parkinsonian disorders, including a frequent overlap of major neuropathological diagnoses (Dugger et al., 2014). In this scenario, a number of questions arise regarding the current clinical and research approaches to the problem of age-related neurodegeneration. These include the pathogenic significance of isolated and mixed proteinopathies and other morbidities in neurodegenerative diseases, their usefulness as defining features of clinicopathologic entities or diagnostic biomarkers, and the rationale of targeting them for therapeutic purposes. The complexities of interpreting the clinicopathologic correlations in a neurobehavioral syndrome with underlying mixed pathologies are illustrated here with a clinical pathologic conference case study.

Case presentation

An 80-year-old, right-handed Caucasian man presented with 2 years of progressive memory problems and difficulties moving his left hand. His first symptoms were subjective memory complaints (e.g., problems remembering people’s names, details of recent conversations and events, and repeating himself). About 6 months after the onset of his memory problems, his left hand began to “lose feeling.” He started dropping objects out of his left hand and it became “useless,” as it failed to “do what [he] [told] it to do.” His left hand tended to hang by his side (without levitation or unconscious grasping), was weak, and developed a resting and action tremor and subjective weakness. While he had no symptoms in other limbs, his deficits significantly impaired performing bimanual tasks. One year after the development of his first symptoms, he developed a slow and shuffling gait, problems with balance, falls, and dysarthria without dysphagia. He later developed navigation difficulties, often making the wrong decision about whether to turn right or left while driving. He denied problems with making plans, multitasking, or completing tasks, but he was noted to be more irritable and easily frustrated. He occasionally displayed an uncharacteristic lack of motivation. He denied depression, anxiety, hallucinations, delusions, dietary changes, or sleep difficulties, although his wife had noted whole-body jerks that occurred singly in the middle of the night. His review of systems was positive for anosmia and decreased facial expression. His medical/surgical history was significant for hypercholesterolemia, hypothyroidism, and remote cholecystectomy and tonsillectomy. He reported no drug allergies. His medications included simvastatin, levothyroxine, aspirin, multivitamins, and glucosamine supplements. The patient was estranged from his parents and siblings, and family history of dementia was uncertain. He had no history of head trauma or developmental problems, but he was a war veteran. He completed college education. He had a 10 pack-year history of cigarette smoking and remote history of alcohol abuse. His blood pressure was 130/78 mmHg and heart rate 66 beats/min. His general physical exam was unremarkable. His neurological exam was significant for difficulties mimicking intransitive hand gestures and left limb kinetic apraxia, with preserved ideational and ideomotor praxis. He had a conjugate gaze, and ocular pursuits and saccades were normal in amplitude and velocity. He had a subtle left upper motor neuron pattern of facial weakness. There was a mild-to-moderate action-more-than-resting tremor of the left arm and occasional dystonic posturing of the left hand. Hand pronation/supination and fist opening/closing were severely impaired on the left. Finger taps on the left were moderately slowed. He was unable to name simple objects placed in either hand, although he could readily name them to visual confrontation. He could identify numbers written on his right palm but not on his left palm. Proprioception was impaired in the left hand only. He had a slightly rigid posture, with slow gait, difficulty with tandem gait, and diminished arm swing on the left.

Neuropsychological testing

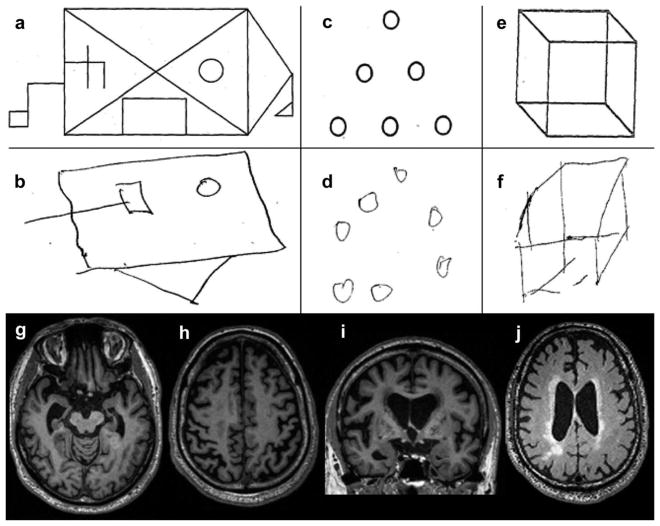

His neuropsychological profile revealed difficulties on measures of visual and verbal episodic memory and impaired visuospatial function. In contrast, language functioning and most aspects of executive function were intact (Table 1 and Figure 1). An interview with his care partner revealed that he remained independent for most activities of daily living. His clinical dementia rating score was 0.5.

Table 1.

Neuropsychological testing*.

| Cognitive domain | Score | Expected score, mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Memory | ||

| CVLT (9) – encoding per trial | 1, 3, 5, 5 | 5.8 (1), 7 (1), 7.4 (1), 8 (1) |

| CVLT (9) – recall at 30 s | 5 | 6.4 (2) |

| CVLT (9) – recall at 10 min | 3 (4 with category cue) | 5.8 (3), cued 6.4 (2) |

| CVLT (9) – recognition (hits/false positives) | 8/8 | 8 (2)/0.8 (1) |

| Modified Rey Osterrieth – recall (17)/recognized | 3/no | 10.2 (3) |

| Visuospatial | ||

| Modified Rey Osterrieth – copy (17) | 12 | 15.6 (1) |

| VOSP (10) | 7 | 8.5 (2) |

| Calculations (5) | 5 | |

| Face perception (12) | 9 | |

| Affect matching (16) | 12 | |

| Language | ||

| BNT (15) | 15 | |

| PPVT (16) | 14 | |

| Sentence comprehension (5) | 4 | |

| Sentence repetition (5) | 4 | |

| Verbal agility (6) | 6 | |

| Executive | ||

| Digit span forward/backward | 6/4 | 6.7 (2)/5.1 (1) |

| Phonemic fluency (words/min) | 18 | 15.9 (5) |

| Semantic fluency (words/min) | 22 | 19.8 (5) |

| Design fluency (designs/min) | 15 | 9.6 (3) |

| Trails – lines, time, errors | 14, 37 sec, 1 | 14, 42 sec (20) |

| Stroop – color naming, errors | 79/0 | 78.9 sec (14) |

| Abstract reasoning (6) | 5 | |

| GDS (30) | 5 | < 9 |

| MMSE (30) | 28 | |

Maximal possible score in parenthesis. Expected score normalized for age and education.

SD: standard deviation; CVLT: California Verbal Learning Test-short form; VOSP: Visual Object Space Perception task; BNT: Boston Naming Test; PPVT: Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; MMSE: Mini-mental State Examination.

Figure 1. Neuropsychological and neuroimaging features in a man with corticobasal syndrome.

(a, b) In the modified Rey Osterrieth figure test, the patient was able to remember only 4 of the 17 figure elements after 10 min; (c, d) his copying of an array of dots was disorganized, and he added an extra dot; (e, f) he copied a three-dimensional cube inaccurately and with the wrong orientation. These findings evidenced visuospatial and visuocontruction deficits localizable to the occipitoparietal cortices; (g) axial views of T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was significant for right-greater-than left hippocampal and entorrhinal cortex atrophy with associated ex-vacuo hydrocephalus of the temporal horn of the lateral ventricles; (h) atrophy was also evident in the bilateral perirolandic cortices; (i) in coronal views, the relative preservation of the temporal neocortex contrasted with mesial temporal, inferior and superior parietal, and insular atrophy; (j) axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images revealed associated right subcortical parietal and periventricular hyperintensities most likely due to chronic microvascular disease.

Neuroimaging studies and genetic testing

Brain MRI revealed severe right-greater-than-left mesial temporal atrophy, with relative preservation of the temporal neocortex. Significant volume loss was also seen in the bilateral right-greater-than-left parietal and mid-insular cortices. The perirolandic cortices showed more severe atrophy than the rostral frontal lobes. Additional significant findings included right greater than left putaminal T2 hyperintensities, suggesting remote lacunar infarcts, and periventricular white matter hyperintensities, with prominent confluent white matter signal in the left parietal centrum semiovale and corona radiata. Genetic testing was negative for pathogenic mutations in PSEN1, PSEN2, APP, GRN, C9ORF72, TARDBP, MAPT, and FUS. Further analyses of dementia-associated risk genotypes included APOEε3/ε3, MAPT A152T G/G, MAPT H1/H2, and GRN rs5848 C/T. The patient died four years later and neuropathology studies were performed.

Clinical differential diagnosis

This patient’s neurocognitive presentation included (1) episodic amnestic syndrome, (2) cortical sensorimotor (perirolandic) syndrome, (3) parkinsonism, and (4) apathy and irritability. The amnestic syndrome appeared first and consisted of episodic verbal and visual memory deficits that correlated with significant asymmetric atrophy of the entorhinal cortex and hippocampal formation. The cortical sensorimotor syndrome consisted of focal subjective weakness, left limb kinetic apraxia, dystonic posturing, impaired imitation of hand gestures, and right lower facial weakness accompanied by tactile agnosia, agraphesthesia, and impaired proprioception. Extrapyramidal features suggested nigrostriatal involvement with potential additional motor fronto-subcortical dysfunction. Finally, anterior cingulate dysfunction is suggested by apathy. The chronic and progressive course is compatible with a neurodegenerative disorder. White matter hyperintensities on brain MRI suggest cerebrovascular disease, which may be a contributing factor. Confluent subcortical white matter hyperintensities may also be indicative of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. There is no strong clinical data supporting an infectious, neoplastic, metabolic/toxic, or autoimmune process. He meets criteria for possible corticobasal syndrome (CBS) given the presence of limb dystonia in combination with cortical sensory deficit and alien limb phenomenon (Armstrong et al., 2013). He had impairments of daily activities stemming primarily from motor symptoms. His memory and visuospatial deficits fit less well with CBS and adds a concern for early stage AD-type dementia spectrum. Early Parkinson’s disease (PD) or PD dementia (PDD) are also possible, although PDD is usually diagnosed when cognitive deficits appear at least 1 year after well-established lateralized extrapyramidal symptoms that are responsive to levodopa. In addition, patients with PDD usually show predominant executive deficits, which are absent in this case. Thus, the patient’s presentation is compatible with CBS and multidomain mild cognitive impairment. In a 10-year retrospective study from our dementia referral center, tauopathies were the underling pathology in about 50% of CBS cases, including corticobasal degeneration (CBD) (35%), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) (12%), Pick’s disease (3%), or multiple system tauopathy (3%) (Lee et al., 2011). The remaining CBS cases were explained by AD (22%), frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TAR DNA binding protein of 43 kDa-immunoreactive inclusions (FTLD-TDP, type A) (12%), or mixed pathology (13%) (Lee et al., 2011). Cases with mixed pathology showed a combination of CBD, PSP, or FTLD-TDP associated with intermediate probability AD. Other reports suggest that CBS may occasionally show underlying Lewy body disease (LBD) (Haug, Boyer, & Kluger, 2013) or sporadic Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease at autopsy (Valverde, Costa, Timoteo, Ginestal, & Pimentel, 2011). Although a primary tauopathy is the most common cause of CBS, a few atypical characteristics argue against FTLD-tau in our patient. Early, profound memory impairment should raise the index of suspicion for AD in a patient with CBS. Sporadic four-repeat (4R) tauopathies, such as CBD or PSP, show patterns of atrophy that usually spare the mesial temporal lobes. Finally, most patients with a 4R tauopathy have an H1/H1 as opposed to an H1/H2 MAPT haplotype (Lee et al., 2011). Thus, mixed pathology should be considered, given the rapid onset and progression of cortical sensorimotor and extrapyramidal signs. In summary, the clinical presentation is compatible with a mixed CBS-amnestic syndrome, possibly due to underlying AD or a mix of FTLD and AD pathology.

Neuropathological evaluation

The fresh brain was obtained 5.8 h after death and weighed 1172 g. Gross atrophy was primarily observed in the medial temporal regions associated with episodic memory processing and in the right frontal, parietal opercular, perirolandic, and insular structures, correlating with left hand movement and praxis deficits. Immunohistochemical analyses revealed a complex pathological picture, showing a high level of AD pathology (Montine et al., 2012), with frequent neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in clinically implicated regions, but also FTLD-TDP, and, more variably, LBD pathology in vulnerable regions (Table 2). Amyloid-beta immunohistochemistry revealed diffuse and neuritic plaques in the neocortex, hippocampus, basal forebrain, and striatum, and reached as far caudally as the midbrain, commensurate with a Thal amyloid plaque phase of 4. Tau neurofibrillary pathology was abundant in the neocortex and homotypical isocortex, consistent with AD Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage 6. This tau neurofibrillary pathology was abundant in the precentral and postcentral gyri, which is uncommon in early stages of typical AD, but is believed to be the most likely cause of the CBS in this case. Limbic, neocortical, and brainstem FTLD-TDP, as well as diffuse neocortical LBD are additional contributing diagnoses that may explain the neuropsychiatric and parkinsonian features, respectively. The FTLD-TDP pathology consisted of small compact/round or crescentic inclusions and short, chaotic neuropil threads, most prominent in superficial layers, which most strongly resembled type A pathology (Mackenzie et al., 2011). The LBD predominated in the substantia nigra and limbic structures but reached the neocortex, earning the designation of diffuse neocortical type (McKeith et al., 2005). In addition, there were three incidentally noted co-morbid pathologies thought to have contributed little, if at all, to the patient’s clinical deficits: (1) limbic argyrophilic grain disease, (2) moderate arteriolosclerosis, and (3) moderate cerebral amyloid angiopathy, as often seen in patients with AD (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Regional severity of neuropathological findings.

| Region | Pathology

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amyloid plaques | Amyloid angiopathy | Tau tangles | Tau neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions | TDP-43 neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions | Synuclein Lewy bodies/neurites | Arteriolosclerosis | |

| Anterior orbital gyrus | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | + + + | − | + + + | − | + | + +/+ + + | + |

| Middle frontal gyrus | + + + | + | + + | − | − | +/+ | + |

| Inferior frontal gyrus, pars opercularis | − | − | + + + | − | − | − | + |

| Subgenual cingulate cortex | − | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| Precentral gyrus | − | − | − | + | + | − | + + |

| Superior frontal sulcus | − | − | + + + | + | − | − | − |

| Middle insula | + + + | − | + + + | + | + + + | − | + |

| Entorrhinal cortex | + + + | − | + + + | − | + + + | + + +/+ + + | − |

| Inferior temporal gyrus | + + + | + | + + + | − | + + + | − | − |

| Superior/middle temporal gyrus | + + + | − | + + + | − | − | − | − |

| Postcentral gyrus | − | − | − | + | + + | − | − |

| Posterior cingulate gyrus | − | − | + + + | + | − | − | − |

| Angular gyrus | + + + | + + | + + + | + | − | − | + + |

| Striate cortex | + + + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Amygdala | − | − | − | − | + + + | + + +/+ + + | − |

| Dentate gyrus | − | − | − | + | + | ± | − |

| CA1-subiculum | + + + | − | + + + | − | + + | − | − |

| CA2 | + | − | + | + + + | + | ± + | − |

| CA3-4 | + + | − | + + | + + | − | +/+ | − |

| Ventral striatum | − | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| Putamen | + + | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| Globus pallidus | − | − | − | − | + | − | + + |

| Subthalamic nucleus | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Thalamus | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Claustrum | + + + | − | + + | + | − | − | + |

| Dentate nucleus | + + + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Substantia nigra | + + + | − | + + | − | − | + + +/+ + + | − |

| Tectum | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Periaqueductal gray | − | − | + | − | − | ± | − |

| Dorsal raphe | − | − | + + | + | − | ± | − |

| Oculomotor nucleus | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Locus ceruleus | − | − | + + + | − | − | +/+ + | − |

| Median raphe | − | − | + + + | − | − | ± + | − |

| Hypoglossal nucleus | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Dorsal efferent nucleus, vagus | − | − | − | − | − | +/+ + | − |

+ = mild, + + = moderate, + + + = severe, − = none.

Figure 2. Alzheimer’s disease-associated multiple proteinopathy underlying corticobasal syndrome.

(a) Effacement of the gray-white matter boundary (white asterisk) within the precentral gyrus. Compare to normal appearing adjacent cortical regions (white arrow). Scale bar = 500 mm; (b) The primary motor cortex displayed severe gliosis, vacuolation, neuronal loss, and neuritic plaques (black arrow) (hematoxylin and eosin, scale bar 500 μm); (c) immunostaining for amyloid-beta in the right angular gyrus with frequent diffuse and neuritic plaques seen throughout the neocortex, hippocampus, basal forebrain, and brainstem nuclei (4G8 anti-amyloid-beta, scale bar 500 μm). Moderate cerebral amyloid angiopathy (inset) involving the leptomeninges (black arrow) and penetrating cortical arterioles (black arrowhead) is also seen; (d) numerous neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads consistent with Alzheimer’s disease pathology were seen in entorrhinal cortex and CA1/subiculum (CP13 anti-hyperphosphorylated tau, scale bar 5 mm); (e) striking phosphorylated tau protein accumulation in the precentral and postcentral gyri, representing advanced, Braak Stage VI Alzheimer’s disease (CP13 anti-hyperphosphorylated tau, scale bar 100 μm). This pathological finding correlates with the corticobasal syndrome and is rarely seen in patients with memory-predominant AD lacking motor features; (f) phosphorylated tau pathology included grains and pre-tangles with perinuclear halos in CA2, classical findings of argyrophilic grain disease (CP13 anti-hyperphosphorylated Tau, scale bar 100 μm); (g) TDP-43 immunohistochemistry revealed compact round or ovoid cytoplasmic inclusions (arrowheads) within dentate gyrus granule cells. Mild-to-moderate FTLD-TDP pathology (TDP-43 antibody, scale bar 50 μm) was found in hippocampus, amygdala, and other regions (Table 2) but was difficult to classify due to sparsity; (h) the middle insula showed more advanced TDP-43 deposition, resembling FTLD-TDP type A, a finding that also co-existed with AD pathology in the primary motor cortex (TDP-43 antibody, scale bar 100 μm); (i) Lewy bodies (inset) and Lewy neurites were observed in the substantia nigra, brainstem, limbic structures, and middle frontal gyrus (anti-alpha-synuclein, scale bar 100 μm).

Discussion

This is a case of AD with an uncommon presentation as CBS. The case illustrates that the etiology of unusual degenerative neurobehavioral syndromes may go beyond simple 1:1 clinicopathological relationships, especially in the elderly. Community-based neuropathology series demonstrate that different brain pathologies not only independently influence cognitive decline, but they also frequently coexist in the aging brain (Rahimi & Kovacs, 2014). For example, TDP-43 inclusions and Lewy bodies are co-pathologies detected in about 40% of patients with AD neuropathology, although their distribution and patterns are different from those seen in FTLD or LBD. FTLD-associated TDP-43 inclusions predominate in insula, cingulate, and frontotemporal regions, whereas in AD they are usually seen in amygdala, hippocampus, and temporal neocortex, only occasionally escaping to the heteromodal association neocortex of the frontal and parietal lobes. Similarly, Lewy bodies are seen in select brainstem and subcortical nuclei in PD, PDD, and DLB, whereas in AD Lewy bodies tend to follow a progressive pattern from the amygdala, where they co-occur in neurons that also have neurofibrillary tangles, to neocortical areas (Hu et al., 2008; Uchikado, Lin, DeLucia, & Dickson, 2006).

It can be argued that the clinical presentation in unusual AD cases is driven by independent pathologies (amyloid-beta, tau, TDP-43, and alpha-synuclein). Their co-occurrence as seen here in a single patient, however, raises the possibility of several candidate mechanistic interactions. Co-occurrence of multiple protein aggregates might, on the one hand, be seen as a marker of proteostasis failure due to upstream pathogenic processes influenced by genetic, epigenetic, metabolic, environmental, or stochastic factors yet to be determined. On the other hand, multiproteinopathy could be interpreted as a phenomenon of “cross-seeding” of one corruptive misfolded protein by another (Giasson et al., 2003). Further studies are required to define the role and meaning of multiple proteinopathies as determinants of common and atypical neurocognitive phenotypes. This case illustrates the principle that coexistence of multiple molecular pathologies in brains of older patients represents the rule rather than the exception (Hu et al., 2008; Jellinger & Attems, 2015; Wilson et al., 2013), which has major potential implications for the development of biomarkers and effective therapies for neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIA, Frontotemporal dementia: genes, images and emotions (AG019724); NIH, 2T32 (AG023481); Hellman Family Foundation and Hillblom Foundation.

Funding

This work was supported by the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation; Hellman Family Foundation; NIH [AG023481]; National Institute of Aging [AG019724].

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: Rojas, Seeley

Acquisition of data: All authors

Analysis, interpretation of data and manuscript drafting: Rojas, Stephens.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Study supervision, administrative, technical, and material support: Seeley.

References

- Armstrong MJ, Litvan I, Lang AE, Bak TH, Bhatia KP, Borroni B, … Weiner WJ. Criteria for the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration. Neurology. 2013;80:496–503. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827f0fd1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugger BN, Adler CH, Shill HA, Caviness J, Jacobson S, Driver-Dunckley E, … Arizona Parkinson’s DC. Concomitant pathologies among a spectrum of parkinsonian disorders. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2014;20:525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giasson BI, Forman MS, Higuchi M, Golbe LI, Graves CL, Kotzbauer PT, … Lee VM. Initiation and synergistic fibrillization of tau and alpha-synuclein. Science. 2003;300:636–640. doi: 10.1126/science.1082324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug A, Boyer P, Kluger B. Diffuse lewy body disease presenting as corticobasal syndrome and progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome. Movement Disorders. 2013;28:1153–1155. doi: 10.1002/mds.25368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu WT, Josephs KA, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Petersen RC, Parisi JE. Temporal lobar predominance of TDP-43 neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 2008;116:215–220. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0400-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinger KA, Attems J. Challenges of multimorbidity of the aging brain: A critical update. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2015;122:505–521. doi: 10.1007/s00702-014-1288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, Rabinovici GD, Mayo MC, Wilson SM, Seeley WW, DeArmond SJ, … Miller BL. Clinicopathological correlations in corticobasal degeneration. Annals of Neurology. 2011;70:327–340. doi: 10.1002/ana.22424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Baborie A, Sampathu DM, Du Plessis D, Jaros E, … Lee VM. A harmonized classification system for FTLD-TDP pathology. Acta Neuropathologica. 2011;122:111–113. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0845-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O’Brien JT, Feldman H Consortium on DLB. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, … Alzheimer’s A. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: A practical approach. Acta Neuropathologica. 2012;123:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi J, Kovacs GG. Prevalence of mixed pathologies in the aging brain. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2014;6:82. doi: 10.1186/s13195-014-0082-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savva GM, Wharton SB, Ince PG, Forster G, Matthews FE, Brayne C, … Ageing S. Age, neuropathology, and dementia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360:2302–2309. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnen JA, Santa Cruz K, Hemmy LS, Woltjer R, Leverenz JB, Montine KS, … Montine TJ. Ecology of the aging human brain. Archives of Neurology. 2011;68:1049–1056. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchikado H, Lin WL, DeLucia MW, Dickson DW. Alzheimer disease with amygdala Lewy bodies: A distinct form of alpha-synucleinopathy. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2006;65:685–697. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000225908.90052.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde AH, Costa S, Timoteo A, Ginestal R, Pimentel J. Rapidly progressive corticobasal degeneration syndrome. Case Reports in Neurological Medicine. 2011;3:185–190. doi: 10.1159/000329820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Yu L, Trojanowski JQ, Chen EY, Boyle PA, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. TDP-43 pathology, cognitive decline, and dementia in old age. JAMA Neurology. 2013;70:1418–1424. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]