Abstract

This essay examines core contributions of a model of psychological well-being (Ryff, 1989; 1995) that has had widespread scientific impact. It drew on distant formulations to identify new dimensions and measures for assessing what it means to be well. Key themes among the 500+ studies using the model are sketched, followed by reflections about why there has been so much interest in this eudaimonic approach to well-being. A final section looks to the future, proposing new directions to illuminate the forces that work against the realization of human potential as well as those that nurture human flourishing and self-realization.

Keywords: Eudaimonia, Purpose in Life, Personal Growth, Health, Inequality, Greed, the Arts

This essay tells the tale behind an article published in Current Directions in Psychological Science (Ryff, 1995) that is one of the top 30 cited articles in APS journals. This work, heralded by Ryff (1989) and elaborated by Ryff & Keyes (1995) and Keyes, Shmotkin, & Ryff (2002), reformulated the meaning and empirical utility of psychological well-being. These publications now have over 15,000 citations. What defined the novelty in the new model is revisited below, giving emphasis to distal sources of inspiration, including Aristotle’s view of eudaimonia. The enthusiastic reception by the scientific community is briefly distilled, and reflections are offered on why so much interest grew up around the model. Final thoughts look to needed future inquiries. An overarching observation is that the scientific task of nurturing better, more realized lives, and relatedly, building better, more just societies requires compelling ideals about what constitute essential parts of being fully human. As recognized by Aristotle over 2,000 years ago, guiding visions of what it means to become the best that one can be are what give the enterprise soul.

The Happening: Infusions from the Past to Enrich Well-Being

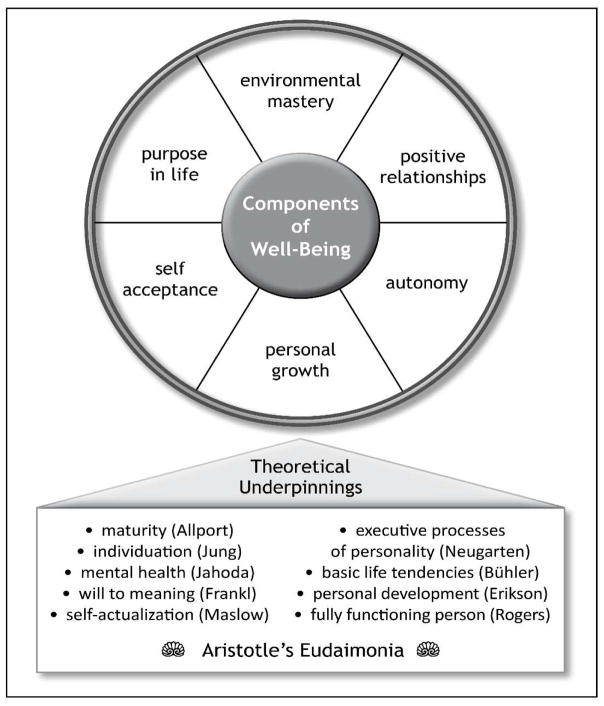

In the middle of the last century, scholars from subfields of psychology embraced the task of articulating the upside of the human experience. Formulations came from clinical (Jahoda, 1958; Jung, 1933), developmental (Bühler, 1935; Erikson, 1959; Neugarten, 1973), existential (Frankl, 1959), humanistic (Maslow, 1968; Rogers, 1961), and social (Allport, 1961) psychology. Their writings delineated numerous characteristics of what it means to be mentally healthy, fully developed, purposefully engaged, self-actualized, fully functioning, and mature. No one perspective stood notably above the rest, but common themes were evident across them. These points of convergence became core components of the model (Ryff, 1989, 1995) that put forth six separate dimensions of well-being depicted in Figure 1. Definitions for each dimension (see Ryff & Singer, 2008) drew from the foundational literatures described above, while also serving as the basis for developing structured self-report tools to operationalize the constructs.

Figure 1.

Core Dimensions of Psychological Well-Being and Their Theoretical Underpinnings.

Reflections about Aristotle’s eudaimonia were present from the beginning and were subsequently elaborated (Ryff & Singer, 2008). He described many virtues in the Nichomachean Ethics (translated by Ross, 1925), but gave primary emphasis to the highest of all virtues, which he saw as growth toward realization of one’s true and best nature. Thus, for Aristotle, the highest of all human goods was activity of the soul in accord with virtue. The key task in life is thus to know and live in truth with one’s daimon, a kind of spirit given to all persons at birth. Eudaimonia embodied the Greek imperatives of self-truth (know thyself) and striving toward an excellence consistent with innate potentialities (become what you are). These ideas deepened the philosophical significance of the new approach to psychological well-being.

The new model stood in marked contrast to other views of subjective well-being at the time, which revolved around assessments of happiness, life satisfaction, and positive and negative affect (Andrews & Withey, 1976; Bradburn, 1969; Campbell, 1981; Diener, 1984; Larson, 1978). These approaches were not centrally concerned with the philosophical meanings of well-being; some, in fact, acknowledged the atheoretical nature of questions about happiness and life satisfaction. Later, Ryan and Deci (2001), in a review marking the new millennium, partitioned the field of well-being into two broad traditions, one dealing with happiness (hedonic well-being) and the other dealing human potential (eudaimonic well-being). Both were traceable to the ancient Greeks. Contemporary psychological research had thus transformed ancient philosophical ideas into empirically tractable science. Using data from a national sample of Americans, Keyes, Shmotkin, and Ryff (2002) provide the first evidence that the two approaches were, indeed, empirically distinct. Thus, a central premise of Ryff (1989), namely that the prior reigning indicators of subjective well-being “neglected important aspects of positive psychological functioning” (p.1070) was scientifically documented. Effectively, contemporary research had embraced new, conceptually-enriched ideas about what it means to be well (self-realized, fully functioning, purposefully engaged).

The Response: Enthusiastic Engagement

The new scales took on a life of their own: they were translated to more than 30 languages from which 500+ publications were generated. A look at this proliferation (Ryff, 2014) revealed several topics of interest, beginning with the psychometric properties of the new scales – did they support a 6-factor model, including in different cultural contexts? When assessed with adequate depth of measurement (long-form scales), most evidence supported the guiding model. Other research addressed developmental questions – what happens to eudaimonic well-being across the decades of adult life? Is it stable or changing? A replicable set of findings brought attention to the challenges of aging: multiple national studies documented longitudinal decline in purpose in life and personal growth in the transition from midlife to old age, thus drawing attention to the contemporary reality that living longer does not necessarily translate to meaningful living.

Other studies contextualized experiences of well-being by linking them to work and family life. Occupational psychologists tied variations in well-being to whether one was engaged in paid or unpaid work, the degree to which work was stressful, and how work life enhanced or undermined family life. Scientists from sociology, human development, family studies, and social work compared levels of well-being between those who were married, single or divorced, or who were parents, including of a child with disabilities. Losses in family life (death of spouse, death of child) and caregiving responsibilities were also linked to well-being. Across these endeavors, the new model offered opportunities to probe how core experiences of adult life related to people’s perceptions of themselves as living by their own convictions (autonomy), being capable (environmental mastery), meaningfully engaged (purpose in life), connected to others (positive relations), realizing their potential (personal growth) and experiencing positive self-regard (self-acceptance).

Arguably the greatest innovations in science followed from eudaimonia’s entry into the health arena. Some studies linked illnesses and disabilities to differing aspects of well-being, while epidemiological studies documented the protective influence of well-being (especially purpose in life) in reducing later life risk for cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and osteoporosis (e.g., Boyle et al., 2010, 2012; Kim et al., 2013). Prospective studies showed extended length of life among those with higher purpose in life (after adjusting for numerous confounds and covariates), including a multi-country meta-analysis (Cohen, Bavishi, & Rozanski, 2016). Underscoring relevance across cultures, the Japanese concept of ikigai, focused on reasons for being, was part of the meta-analysis.

Further science began looking for mediators to account for the above health benefits, such as practicing better health behaviors (e.g., Kim, Strecher, & Ryff, 2014). The biological correlates of well-being received extensive attention with numerous studies showing that higher eudaimonia was linked with better physiological regulation measured in terms of stress hormones, inflammatory markers, glucose regulation, cardiovascular risk factors, and allostatic load (Zilioli et al., 2015). Some physiological benefits were also documented among disadvantaged segments of society, thereby underscoring the resilience-promoting features of purposeful life engagement, personal growth, and positive ties to others in the face of inequality and limited life chances (e.g., Morozink, Friedman, Coe, & Ryff, 2010). Gene expression involved in inflammatory processes has been linked to well-being, with findings showing salubrious effects for eudaimonic but not hedonic well-being (e.g., Cole, Levine, Arevalo, et al., 2015).

The neuroscience of eudaimonia was launched: findings documented better emotional recovery from negative stimuli among those with higher levels of purpose in life and that eudaimonic well-being is involved in activation of brain regions involved in emotion and executive function. Sustained engagement of reward circuitry in response to positive stimuli was evident among those with higher eudaimonic well-being, a pattern further linked to lower diurnal cortisol profiles (Heller, van Reekum, Schaefer et al., 2013). Eudaimonic well-being was also linked with greater insular cortex volume, which is involved in a variety of higher-order functions (see Ryff et al., 2016 for further neuroscience findings).

Clinical applications have grown up around eudaimonic well-being. Intervention studies focused on the promotion of well-being as new targets for treatment to prevent relapse of major depression and to reduce symptoms of anxiety. Interventions have also been extrapolated beyond the clinic to schools, workplace settings, and community centers for older adults. Collectively, these endeavors seek to enhance well-being as a strategy prevent mental illness and promote resilience (see Ruini & Ryff, 2016 for more detail).

Finally, a new Handbook on Eudaimonia (Vittersó, 2016) includes 38 chapter by leading psychologists from around the world, all focused on a topic largely absent in scientific research only decades ago. Not all such work is guided by Ryff (1989, 1995), though it is referred to as a classic in the introductory chapter. Reflections about why this widespread transformation in the science of well-being occurred are below.

The Accounting: Why All the Interest?

Three explanations are offered for why the new model attracted widespread interest from the scientific community.

Intellectually Vital Ideas and Ideals

Contemporary science needs to grapple with fundamental questions of the human condition, such as how we should live. Further, responses need to be guided by intellectually vital, indeed, beautiful ideas and ideals (Ryff, 2016a). Thus, one reason why the new model of well-being had wide ranging impact is that it reaches, in the fashion of Aristotle, for essential meanings of what constitutes the best that is within us. His timeless insights, combined with later input from existential, humanistic, developmental, and clinical psychology, reconfigured well-being so that it had philosophical and spiritual gravitas (the soul part). Stated otherwise, one might say that scientists from diverse disciplines recognize a compelling model when they see it, and then choose to adopt in investigating the questions that motivate their work. This is a phenomenon of resonating to what matters in life when it is distilled from vital, nourishing wellsprings.

Scientific Relevance and Versatility

Many topics in psychology have relevance across wide domains of inquiry. Well-being is one – as conveyed by the above glimpse of findings. Questions about core aspects of living (life course development, work and family life, health and related biological mechanisms, neuroscience, inequality), including how they vary by cultural context, are advanced with thoughtfully formulated ideas about well-being. In addition, the indicators themselves have unique versatility, serving sometimes as antecedent variables (does eudaimonic well-being promote longer life?), sometimes as consequent variables (does age, or ethnicity, or socioeconomic status, or culture predict differing levels of eudaimonic well-being?), and increasingly as moderating variables (does eudaimonic well-being buffer against the adverse health effects of inequality or the challenges of aging?). Simply put, a rich formulation of well-being, because it matters for so many aspects of the human experience, is destined for scientific omnipresence.

Embracing Integrative Science

Great science often involves drilling down with ever greater precision and focus. Increasingly, there is recognition that big picture science, which puts expertise across differing fields together, is also needed. Such science is illustrated by the MIDUS (Midlife in the U.S.) national longitudinal study (www.midus.wisc.edu), which brought together scientists from population-level disciplines (demography, epidemiology, sociology) to collaborate with scientists (many from psychology) focused on behavioral, biological, and neuroscientific mechanisms and processes. MIDUS also blended longitudinal and experimental methods in collecting vast amounts of data (sociodemographic factors, psychosocial factors, chronic and acute life stress, responses to laboratory challenges, biomarkers, neuroimaging assessments, health status, mortality) on the same respondents followed repeatedly through time. To probe cultural influences on biopsychosocial integration, a parallel longitudinal study known as MIDJA (Midlife in Japan) was also launched.

The publicly available data from both studies have had a tremendous response from the scientific community: more than 30,000 unique users and 800+ publications have been generated. One prominent area of inquiry has been psychological well-being (150+ publications), assessed with a comprehensive battery of eudaimonic and hedonic measures. Thus, a further explanation for the proliferation of research described in this essay is the emergence of big, multidisciplinary, public-use studies like MIDUS and MIDJA.

New Directions: Forces Against and For Eudaimonia

Paradoxically, research on the upside of the human experience often requires focusing on the downside – the forces that compromise human potential and self-realization. Inequality, now evident on a global scale, is one such force. Scientists, including many psychologists, now study inequalities in health. Most work focuses on the adversities experienced by disadvantaged groups and how they compromise health and ultimately shorten lives. Missing is research at the other end of the hierarchy – namely, the problem of greed among privileged elites, a likely root cause of inequality. Akin to well-being, greed has timeless qualities. Along with fraud and dishonesty, Dante placed the sins of greed and gluttony in his nine circles of hell in The Divine Comedy (14th century). Adam Smith promoted self-interest in his Wealth of Nations (18th century), but also recognized the problem of greed, depicted by him as the limitless appetites of the vain and insatiable. The ancient Greeks were also concerned about problems of greed and injustice (Balot, 2001), which they saw as contributing to civic strife.

Future research needs to better understand how the greed of the few who sit in positions power and leadership in companies, organizational settings, universities, local communities and national governments matters for the well-being of those below them in the status hierarchies. This is not entirely novel territory: motivational psychologists previously linked the quest for money to lower well-being (Kasser & Ryan, 1993), while social psychologists have shown that higher social class standing is linked with increased entitlement, narcissism and more unethical behavior compared to lower class standing (Piff, 2014; Piff et al., 2012). Economists have focused on “values-based organization” (Bruni & Smerilli, 2009) wherein core objectives are examined – are they tied to ideals greater than profit and material incentives? Such values are then examined as explanations for which organizations flourish and which deteriorate over time. Economists have also drawn attention to relevant behaviors in the corporate world – i.e., dramatic differences in the size of yearly bonuses for those at the top relative to salaries of lower-echelon workers (Piketty, 2014)., New studies are needed that build on these lines of inquiry by bringing facets of greed (extrinsic motivation, sense of entitlement, narcissism, need for power, selfishness, unethical behavior) into real-world contexts. The key task is to explicate what manifestations of greed at the top means for others – specifically, how do the behaviors and values of self-serving versus beneficent leaders matter for the eudaimonic well-being (especially aspects of purpose in life, personal growth, and self-acceptance) of those over whom they wield great influence?

Equally, if not more important, for the future are studies on the forces for eudaimonia – namely, what elements of life enrich and nourish the realization of human potential? One promising direction involves bringing the arts and humanities into research on eudaimonic well-being. Evidence on multiple fronts suggest now is an auspicious time for such inquiry. In medical fields, there is growing recognition that philosophy, literature, poetry, art, film, music afford benefits in health and healthcare and contribute to more compassionate physicians (Crawford et al., 2015; Stuckey & Nobel, 2010). A recent report entitled “The Arts, Health, and Well-Being” from the Royal Society for Public Health in the United Kingdom (2013) elaborates on these ideas. here is also growing interest within the arts and humanities in demonstrating their role in nurturing well-lived lives and good societies via the identification of key ideals and the meaning-making practices of culture (Edmondson, 2004, 2015; Nussbaum, 2010; Small, 2013). Such messages are critically important as we witness the declining status of the arts and humanities within the academy (Hanson & Health, 2998) and reduced participation of citizens in art exhibits and the performing arts (Cohen, 2013).

From the world of museums, there is interest among curators in making their holdings of greater interest and relevance to the general public, including those who are economically and educationally disadvantaged, or even incarcerated (Mid Magasin, 2015). Such efforts bring principles of social justice to the museum world. Related activities conceive of new ways to encounter literature and art so that they provoke and enrich people’s lives (de Botton, 1997, 2013). Finally, within psychology and education, there is heightened interest in how the arts, broadly defined, contribute to diverse aspects of well-being (Lomas, 2016; Ryff, 2016b). These directions signal a return to insights from Dewey(1934) about how we experience art and how it matters in our lives. Contemporary educators now claim that the promotion of well-being, rather than economic gain, should be the primary goal of higher education (Harward, 2016).

In sum, key ideals of eudaimonia are to be virtuous and to grow. Applied to the science of well-being, these require caring about the things that make human lives, and the world in which we live, better. Socially relevant research must thus embrace the pernicious forces that work against eudaimonia and fuel unjust societies, while also attending to the beautiful and sublime aspects of life that nurture experiences of purposeful engagement, meaningful living, and self-realization.

References

- Allport GW. Pattern and growth in personality. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle . In: The Nicomachean Ethics. Ross WD, translator. New York: Oxford University Press; 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Balot RK. Greed and injustice in classical Athens. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Buckman AS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimers disease and mild cognitive impairment in community- dwelling older persons. Archives General Psychiatry. 2010;67:304–310. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PO, Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Yu L, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Effect of purpose in life on the relation between Alzheimer disease pathologic changes on cognitive function in advanced age. Archives General Psychiatry. 2012;69:499–506. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni L, Smerilli A. The value of vocation: The crucial role of intrinsically motivated people in values-based organizations. Review of Social Economy. 2009;67:271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Bühler C. The curve of life as studied in biographies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1935;43:653–673. doi: 10.1037/h0054778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. The New York Times. 2013. Sep 26, A new survey finds drop in art attendance. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R, Bavishi C, Rozanski A. Purpose in life and its relationship to all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2016;78:122–133. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000274. doi:20.2097/psy.0000000000000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Levine ME, Arevalo JMG, Ma J, Weir DR, Crimmins EM. Loneliness, eudaimonia, and the human conserved transcriptional response to adversity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;62:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford P, Brown B, Baker C, Tischler V, Abrams B. Health humanities. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dante . In: The divine comedy. Longfellow HW, Amari-Parker A, translators. New York: Chartwell Books, Inc; 1308/2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Botton A. How Proust can change your life: Not a novel. Visalia, CA: Vintage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- De Botton A, Armstrong A. Art as therapy. London, UK: Phaidon Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey J. Art as experience. New York: Penguin; 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson M. Self and soul: A defense of ideals. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson M. Why read? New York, NY: Bloomsbury; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity and the life cycle: Selected papers. Psychological Issues. 1959;1:1–171. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl VE. Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Harward DW. Well-being and higher education: A strategy for change and the realization of education’s greater purposes. Washington, D.C: Bringing Theory to Practice; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Heller AS, van Reekum CM, Schaefer SM, Lapate RC, Radler BT, Ryff CD, Davidson RJ. Sustained ventral striatal activity predicts eudaimonic well-being and cortisol output. Psychological Science. 2013;24(11):2191–2200. doi: 10.1177/0956797613490744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda M. Current concepts of positive mental health. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Jung CG. In: Modern man in search of a soul. Dell WS, Baynes CF, translators. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World; 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T, Ryan RM. A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;65:410–422. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM, Shmotkin D, Ryff CD. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:1007–1022. doi: 10.1037/0022.3514.82.6.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES, Strecher VJ, Ryff CD. Purpose in life and use of preventive health care services. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(46):16331–16336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414826111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES, Sun JK, Park N, Kubzansky LD, Peterson C. Purpose in life and reduced risk of myocardial infarction among older U.S. adults with coronary heart disease: a two-year follow-up. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2013;36:124–133. doi: 10.1007/sl0865.012.2906.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas T. Positive art: Artistic expression and appreciation as an exemplary vehicle for flourishing. Review of General Psychology. 2016;10:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. Toward a psychology of being. 2. NY: Van Nostrand; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Magasin MiD. Museumformidlere i Denmark. 2015. Why museums? 32, Marts. [Google Scholar]

- Morozink JA, Friedman EM, Coe CL, Ryff CD. Socioeconomic and psychosocial predictors of interleukin-6 in the MIDUS national sample. Health Psychology. 2010;29(6):626–635. doi: 10.1037/a0021360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugarten BL. Personality change in late life: A developmental perspective. In: Eisodorfer C, Lawton MP, editors. The psychology of adult development and aging. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1973. pp. 311–335. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum MC. Not for profit: Why democracy needs the humanities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Piff PK. Wealth and the inflated self: Class, entitlement and narcissism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2014;40:34–43. doi: 10.11770/0146167213401699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piff PK, Stancato DM, Côté S, Mendoza-Denton R, Keltner D. Higher social class predicted increased unethical behavior. Proceedings of the National Academies of Science (PNAS) 2012;109:4086–4091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118373109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piketty T. In: Capital in the twenty-first century. Goldhammer A, translator. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CR. On becoming a person. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Society and Public Health Working Group. Arts, health and well-being beyond the millennium: How far have we come where do we want to go? London, UK: Royal Society for Public Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57(6):1069–1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruini C, Ryff CD. Using eudaimonic well-being to improve lives. In: Wood AM, Johnson J, editors. Wiley Handbook of Positive Clinical Psychology. West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell; 2016. pp. 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Psychological well-being in adult life. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4:99–104. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2014;83(1):10–28. doi: 10.1159/000353263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Beautiful ideas and the scientific enterprise: Sources of intellectual vitality in research on eudaimonic well-being. In: Vittersó J, editor. The Handbook of Eudaimonia. New York: Springer; 2016a. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Eudaimonic well-being and education: Probing the connections. In: Harward DW, editor. Well-being and higher education: A strategy for change and the realization of education’s greater purposes. Washington, DC: Bringing Theory to Practice; 2016b. pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer BH. Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2008;9(1):13–39. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Heller AS, Schaefer SM, van Reekum C, Davidson RJ. Purpose engagement, healthy aging, and the brain. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s40473-016-0096-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small H. The value of the humanities. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. In: An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations: Two volumes. Campell RH, Skinner AS, editors. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Press; 1776/1981. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey HL, Nobel J. The connection between art, healing, and public health: A review of current literature. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:254–263. doi: 10.2105/ALPH.2008.156497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittersó J, editor. Handbook of eudaimonia. New York: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zilioli S, Slatcher R, Ong AD, Gruenewald TL. Purpose in life predicts allostatic load ten years later. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2015;79:451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]