Abstract

Fibrils of the protein α-synuclein are implicated in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease and related neurodegenerative disorders. We have reported a high-resolution structure (PDB 2N0A) of an α-synuclein fibril form prepared by in vitro incubation of monomeric protein in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 with 0.1 mM EDTA and 0.01% sodium azide. In parallel with this structure determination, ongoing studies of small molecule ligands binding to α-synuclein fibrils, prepared in 2-amino-2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-propanediol (Tris) buffer, have been in progress, and it is therefore of interest to determine the structural similarity of these forms. Here we report the 13C and 15N resonance assignments for α-synuclein fibrils prepared with Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.7 at 37°C) and 100 mM NaCl. These fibrillization conditions yield a form with fibril core chemical shifts highly similar to those we reported (BMRB 16939) in the course of determining the high-resolution 2N0A structure, with the exception of some small perturbations from T44 to V55, including two sets of peaks observed for residues T44 to V48. Additional differences occur in the patterns of observed residues in the primarily unstructured N-terminus. These results demonstrate a common fold of the fibril core for α-synuclein fibrils prepared in phosphate or Tris-HCl buffer at moderate ionic strength.

Keywords: α-synuclein, fibril, polymorphism, Parkinson’s disease

BIOLOGICAL CONTEXT

The protein α-synuclein (α-syn) aggregates to form fibrils that define the pathology of several neurodegenerative disorders including Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) (Spillantini et al. 1997; Spillantini et al. 1998). One highly ordered form of α-syn fibrils is generated when purified, monomeric α-syn is incubated at 37°C with 200 rpm shaking at a concentration of 15 mg/mL in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 with 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.01% sodium azide (Kloepper et al. 2006). We previously performed a detailed assignment (Comellas et al. 2011a) and structure determination (2N0A, Tuttle et al. 2016a) of this fibril form. Meanwhile, we and others have studied a variety of α-syn fibril forms by SSNMR and found that the conditions of incubation can yield different structural fingerprints (Heise et al. 2005; Gath et al. 2012; Comellas et al. 2012; Gath et al. 2014), as evidenced by the SSNMR spectra, although only one high-resolution structure so far has been determined. Better understanding the range of stable α-syn fibril forms is significant in order to shed light on strain-dependent pathologies and toxicities, a phenomenon observed in cell cultures (Bousset et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2013) and rats (Peelaerts et al. 2015).

Here, we report the 15N and 13C chemical shift assignments for an α-syn fibril sample prepared in Tris-HCl buffer at moderate ionic strength. These conditions were chosen to provide structural data on the fibril form previously utilized for the development of the synuclein imaging ligand (SIL) series of small molecules for quantification of α-syn fibril accumulation by positron emission tomography (PET) imaging (Yu et al. 2012; Bagchi et al. 2013; Chu et al. 2015). Compounds from the SIL series display binding affinity for this α-syn fibril form that is similar to the binding affinity measured in assays with insoluble fractions from postmortem PD brain tissue (Bagchi et al. 2013). Therefore we chose to perform the present NMR study to evaluate structural similarity and establish whether the previously determined structure is a valid basis for structure-based design. We find, based on a comparison of the NMR chemical shifts, that the α-syn fibril prepared in Tris-HCl at moderate ionic strength exhibits a similar core structure to fibrils prepared in phosphate buffer.

METHODS AND EXPERIMENTS

Protein Expression and Purification

Uniformly 13C, 15N-labeled wild-type α-syn was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET28a-AS grown in Studier medium M containing 2 g/L [13C]glucose, 3 g/L [15N]ammonium chloride, and 10 mL/L [13C, 15N]Bioexpress (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc., Tewksbury, MA). Cells were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of 1.2, protein expression induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside, and grown at 25°C for 15 h prior to harvest. The cell lysis, heat denaturation, and ammonium sulfate precipitation was performed as described (Kloepper et al. 2006). The precipitated α-syn protein was solubilized in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8 and loaded onto a QFF anion exchange column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA). Elution was carried out with a linear gradient of 0.2-0.6 M NaCl. The α-syn monomer eluted around 0.3 M. Fractions containing α-syn were pooled, concentrated, and applied to a 26/60 Sephacryl S-200 HR gel filtration column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8 buffer with 100 mM NaCl and 0.01% sodium azide. Fractions containing α-syn were pooled and stored at a concentration of about 1 mg/mL at 4°C until use. Purity was determined to be >95% by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and molecular weight was confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry.

Generation of α-syn fibrils

Protein was concentrated to 15 mg/mL using an Amicon stirred cell concentrator (EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and stored quiescent at 4°C during the course of each addition described here. Prior to each addition, the monomer was filtered using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter unit with a 50 kDa nominal molecular weight limit (EMD Millipore). Fibrillization was performed using a method similar to protein-misfolding cyclic amplification used to amplify prion protein (Saborio et al. 2001). The seed fibrils were produced using natural-abundance α-syn monomer as described (Bagchi et al. 2013). The fibrils were separated from monomer by centrifugation at 15,000 g for 15 min in 1.5 mL ultracentrifuge tubes (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). The fibrils were amplified by addition of uniformly 13C, 15N-labeled α-syn monomer in a 1:1 ratio by volume. The volume of pellet was estimated to be 25 μL. The tubes were then vortexed and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C with 200 rpm shaking. This process of adding fresh monomer, vortexing, and incubating was repeated a total of eight times. Following the final addition, the samples were incubated for three weeks. The seeds were prepared in 20 mM Tris-HCl and the amplification was performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl. After incubation, the fibrils were harvested by ultracentrifugation, washed with ultrapure water, dried under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas, packed in a 3.2 mm limited speed rotor (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), and rehydrated with water, as described (Tuttle et al. 2016b).

Solid-State NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were collected using an Infinity Plus spectrometer, manufactured in 2003 by Varian (Palo Alto, CA, Walnut Creek, CA and Fort Collins, CO) and an Oxford Instruments (Oxford, UK) wide-bore (89 mm) superconducting magnet operating at a static magnetic field of 14.1 T (600 MHz 1H frequency) equipped with a Balun 3.2-mm triple-resonance (1H, 13C, 15N) probe (Varian, Fort Collins, CO). Spinning was controlled using a Varian magic-angle spinning (MAS) controller to 13,333 ± 5 Hz and a variable-temperature (VT) air-flow setting of −10°C, resulting in an actual sample temperature of −3 ± 3°C as determined by calibration with ethylene glycol. Sequential backbone and side-chain chemical shift assignments were made using a combination of CC, NCA, and CA(NCO)CX 2D spectra as well as NCACX, NCOCX, CANCO, and CAN(CO)CX 3D spectra (Comellas and Rienstra 2013). All experiments used 1H-13C or 1H-15N tangent ramped cross-polarization (CP) (Metz et al. 1994) and ~75 kHz SPINAL-64 decoupling during evolution and acquisition periods (Fung et al. 2000), optimized as described (Comellas et al. 2011b). Where utilized, CC mixing was performed with 50 ms DARR (Takegoshi et al. 2001). The 15N 1D CP-MAS spectrum used to investigate the H50 Nδ1/Nε2 shifts was collected on a Varian VNMRS spectrometer and wide-bore magnet operating at 11.7 T (500 MHz 1H frequency) with a MAS rate of 11,737 ± 8 Hz and VT setting of 10°C, corresponding to an actual sample temperature of 14 ± 3°C. Details on the SSNMR experiments are located in Supplementary Table 1. Chemical shifts were referenced externally to the downfield peak of adamantane at 40.48 ppm (Morcombe and Zilm 2003). Data were converted and processed with NMRPipe (Delaglio et al. 1995). In the direct dimensions, back-linear prediction and polynomial baseline correction was used. Time domain data was zero-filled, Fourier transformed, and apodized using Lorentzian-to-Gaussian line broadening and/or sine bells to optimize line shapes and resolution. Peak picking was performed using Sparky (Goddard and Kneller 2006).

ASSIGNMENTS AND DATA DEPOSITION

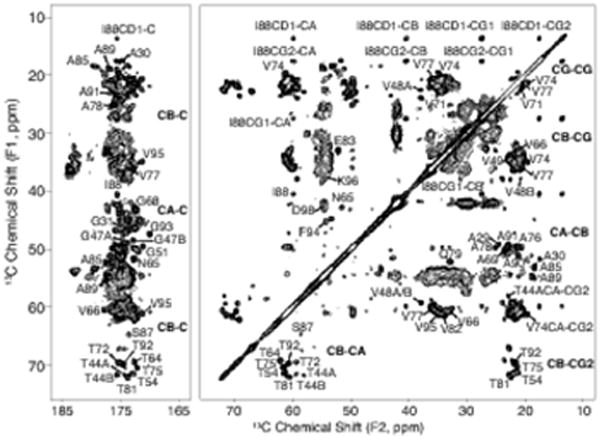

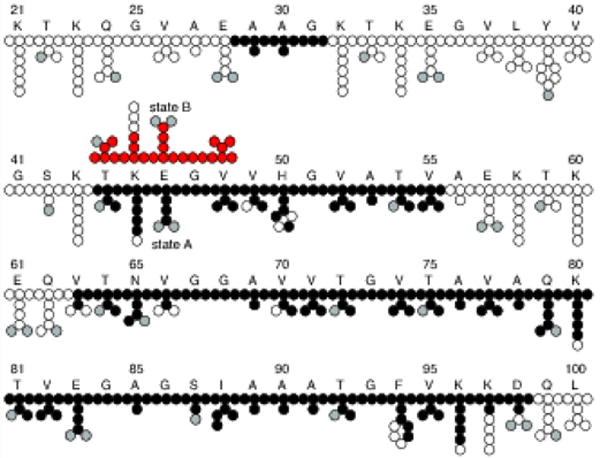

The SSNMR experiments and chemical shift assignments reported here were performed using a single U-13C, 15N labeled α-syn fibril sample. The MAS rotor contained 17 mg of fibrils hydrated to 40±10% (w/w) with water as determined by 1H NMR. A CC 2D spectrum collected with 50 ms DARR mixing, 20 ms indirect evolution, and 20 ms direct acquisition is shown in Fig. 1. For clarity, only unique and well-resolved assignments are labeled on the spectrum. Residues that have fully resolved spin systems in the 2D, with signal-to-noise (S/N) of individual peaks greater than 20, include A30, G51, T54, N65, T75, A85, I88, A89, T92, and G93. Backbone walk assignments were performed using a suite of 3D spectra (NCACX, NCOCX, and CANcoCX). Typical line widths in the 3Ds were 0.5 ppm for 15N, 0.4 ppm for the indirect 13C dimensions, and 0.5-0.8 ppm for the direct 13C dimension. We assigned a continuous backbone stretch and most side chains for residues V63 to D98, which comprise most of the rigid fibril core. In addition, we assigned the backbone and most side chain atoms for the stretch from T44 to V55, as well as a three-residue stretch from A29 to G31 (Fig. 2). Residues T44 to V48 exhibit two sets of peaks, which we refer to as state A and state B. The assignments are deposited in the BMRB under accession number 26890. The majority of resonances exhibit secondary chemical shifts consistent with β-strand structure.

Fig. 1.

C- C correlation spectrum of U-13C, 15N α-synuclein fibril sample showing the carbonyl and aliphatic regions. Data was acquired with 50 ms DARR mixing, 20.48 ms acquisition, and 20.48 ms t1 evolution and processed with 30 Hz net Lorenzian-to-Gaussian line broadening and a second order 50° shifted sine bell. The first contour is cut at 13 times the root-mean-square noise. Residues T44 - V48 exist in two states, labeled A and B

Fig. 2.

Assigned atoms showing residues K21 to L100 out of 140 total amino acids in the α-synuclein primary sequence. Atoms with assignments are represented as filled black circles, filled gray circles are oxygen, and empty circles are unassigned or left empty due to uncertainty in the assignment. Atoms from residues T44 - V48 have two sets of peaks referred to here as states A and B. The atoms for state B are filled red for clarity

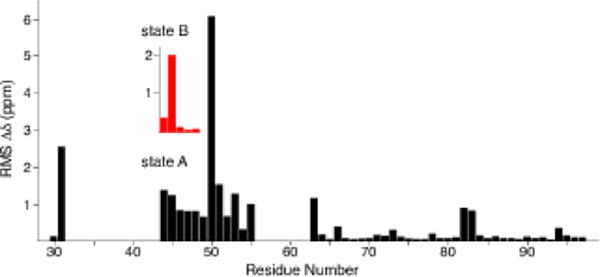

We compared the chemical shifts with the assignments corresponding to Comellas et al. 2011a (BMRB 16939). The chemical shift perturbations are localized primarily at the most N-terminal β-strand (residues T44 to V55), with larger perturbations observed for G31 and H50 (Fig. 3). In addition, the H50 Cδ2 and Cε1 signals are assigned and the H50 Nδ1/Nε2 signals appear as sharp peaks at 166.3 and 255.3 ppm in the 15N 1D CP spectrum, which were not observed previously. Residues T44 to V48 exhibit large perturbations for state A, but perturbations are only observed for K45 for state B, relative to BMRB 16939. Additional individual perturbations are observed for residues (such as V63, V82 and E83) located on the periphery of the structure. The assignments for the fibril core are highly similar between these two forms, suggesting that the fold is conserved despite the differences in incubation conditions. Thus, the fibril form produced under the incubation conditions used here—i.e., similar to those used for development of α-syn imaging agents— appears to exhibit the same fibril core arrangements as the recently reported structure (2N0A, Tuttle et al. 2016a).

Fig. 3.

Plot of weighted average chemical shift perturbations for all assignments common between the sample studied here and Comellas et al. 2011a (BMRB 16939) for which we solved the structure (PDB code 2N0A, BMRB 25518, (Tuttle et al. 2016a)). The inset with red bars shows the chemical shift perturbations for state B of residues T44 - V48. RMS Δδ was calculated as (Σ_(ΔδCi)2 + (0.4 * ΔδN,)2 }1/2, where i refers to α, β, γ, δ, and ε

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01-GM073770 (to C.M.R.), a Michael J. Fox Foundation grant for nuclear magnetic resonance analysis to support development of alpha-synuclein imaging agents (to C.M.R.), and a Michael J. Fox Foundation Alpha-Synuclein Imaging Consortium grant to support development of alpha-synuclein imaging agents (to P.T.K.). A.M.B. is a trainee of the NIH Molecular Biophysics Training Grant at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (T32-GM008276). J.M.C. is a recipient of a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. We thank Deborah A. Berthold for help with sample preparation.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBER

Chemical shift assignments for α-synuclein fibrils prepared in Tris buffer at moderate ionic strength can be accessed on the BioMagResBank (BMRB) under entry number 26890.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Table S1 Experimental details of SSNMR experiments used to make 13C and 15N chemical shift assignments of α-synuclein fibrils

References

- Bagchi DP, Yu L, Perlmutter JS, et al. Binding of the radioligand SIL23 to α-synuclein fibrils in Parkinson disease brain tissue establishes feasibility and screening approaches for developing a parkinson disease imaging agent. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousset L, Pieri L, Ruiz-Arlandis G, et al. Structural and functional characterization of two alpha-synuclein strains. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2575. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu W, Zhou D, Gaba V, et al. Design, synthesis, and characterization of 3-(Benzylidene)indolin-2-one derivatives as ligands for α-synuclein fibrils. J Med Chem. 2015;58:6002–6017. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comellas G, Lemkau LR, Nieuwkoop AJ, et al. Structured regions of α-synuclein fibrils include the early-onset Parkinson’s disease mutation sites. J Mol Biol. 2011a;411:881–895. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comellas G, Lopez JJ, Nieuwkoop AJ, et al. Straightforward, effective calibration of SPINAL-64 decoupling results in the enhancement of sensitivity and resolution of biomolecular solid-state NMR. J Magn Reson. 2011b;209:131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comellas G, Lemkau LR, Zhou DH, et al. Structural intermediates during α-synuclein fibrillogenesis on phospholipid vesicles. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:5090–5099. doi: 10.1021/ja209019s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comellas G, Rienstra CM. Protein structure determination by magic-angle spinning solid-state NMR, and insights into the formation, structure, and stability of amyloid fibrils. Annu Rev Biophys. 2013;42:515–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, et al. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based On UNIX Pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung BM, Khitrin AK, Ermolaev K. An improved broadband decoupling sequence for liquid crystals and solids. J Magn Reson. 2000;142:97–101. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gath J, Habenstein B, Bousset L, et al. Solid-state NMR sequential assignments of α-synuclein. Biomol NMR Assign. 2012;6:51–55. doi: 10.1007/s12104-011-9324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gath J, Bousset L, Habenstein B, et al. Yet another polymorph of α-synuclein: solid-state sequential assignments. Biomol NMR Assign. 2014;8:395–404. doi: 10.1007/s12104-013-9526-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY 3. University of California; San Francisco: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Guo JL, Covell DJ, Daniels JP, et al. Distinct α-synuclein strains differentially promote tau inclusions in neurons. Cell. 2013;154:103–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise H, Hoyer W, Becker S, et al. Molecular-level secondary structure, polymorphism, and dynamics of full-length α-synuclein fibrils studied by solid-state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15871–15876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506109102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloepper KD, Woods WS, Winter KA, et al. Preparation of α-synuclein fibrils for solid-state NMR:expression, purification, and incubation of wild-type and mutant forms. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;48:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz G, Wu X, Smith SO. Ramped-amplitude cross polarization in magic-angle-spinning NMR. J Magn Reson Ser A. 1994;110:219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Morcombe CR, Zilm KW. Chemical shift referencing in MAS solid state NMR. J Magn Reson. 2003;162:479–486. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(03)00082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peelaerts W, Bousset L, Van der Perren A, et al. α-synuclein strains cause distinct synucleinopathies after local and systemic administration. Nature. 2015;522:340–344. doi: 10.1038/nature14547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saborio GP, Permanne B, Soto C. Sensitive detection of pathological prion protein by cyclic amplification of protein misfolding. Nature. 2001;411:810–813. doi: 10.1038/35081095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM-Y, et al. α-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, et al. α-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6469–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takegoshi K, Nakamura S, Terao T. 13C-1H dipolar-assisted rotational resonance in magic-angle spinning NMR. Chem Phys Lett. 2001;344:631–637. [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle MD, Comellas G, Nieuwkoop AJ, et al. Solid-state NMR structure of a pathogenic fibril of full-length human α-synuclein. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016a;23:409–415. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle MD, Courtney JM, Barclay AM, Rienstra CM. Protein Amyloid Aggregation. In: Eliezer D, editor. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 2016b. pp. 173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Cui J, Prashanth PK, et al. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of α-synuclein ligands. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:4625–4634. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.