Abstract

Poly(A) tails are important elements in mRNA translation and stability. However, recent genome-wide studies concluded that poly(A) tail length was generally not associated with translational efficiency in non-embryonic cells. To investigate if poly(A) tail size might be coupled to gene expression in an intact organism, we used an adapted TAIL-seq protocol to measure poly(A) tails in Caenorhabditis elegans. Surprisingly, we found that well-expressed transcripts contain relatively short, well-defined tails. This attribute appears dependent on translational efficiency, as transcripts enriched for optimal codons and ribosome association had the shortest tail sizes, while non-coding RNAs retained long tails. Across eukaryotes, short tails were a feature of abundant and well-translated mRNAs. Although this seems to contradict the dogma that deadenylation induces translational inhibition and mRNA decay, it instead suggests that well-expressed mRNAs accumulate with pruned tails that accommodate a minimal number of poly(A) binding proteins, which may be ideal for protective and translational functions.

Keywords: poly(A) tail, translation, PABP, C. elegans

During transcriptional termination, the majority of eukaryotic mRNAs undergo polyadenylation, resulting in a 3’ tail estimated to contain ~90 (yeast) or ~250 (animals) adenosines1. The poly(A) tail has been shown to be important for protection and translation of the mRNA2,3. These roles are largely mediated by poly(A) binding proteins (PABPs), which coat the tail1. The direct interaction of PABP with the 5’ cap binding complex factor eIF4G is thought to promote mRNA stability and translation by supporting formation of the closed-loop state1–3. Conversely, PABP also binds deadenylation complexes (CCR4-NOT-Tob and PAN2-PAN3) and contributes to microRNA-mediated repression4–6. These seemingly contradictory roles of PABP suggest that poly(A) tail length and, hence, the number of bound PABPs might determine mRNA fate.

In early embryos and other cellular contexts, regulated cytoplasmic polyadenylation lengthens the tails of select mRNAs, resulting in their translational activation7. Yet, recent studies that measured poly(A) tails of individual transcripts genome-wide did not identify a general association between tail size and translational efficiency in most somatic cells8–10. Only transcripts containing poly(A) tails shorter than 20 nt were found to have reduced translational efficiency in cultured cells9. Consistent with single gene studies showing the importance of tail length and translation in early embryogenesis7, recent genome-wide analyses of poly(A) tails in frog, zebrafish and Drosophila early embryos confirmed a positive correlation between tail length and translational efficiency in pre-gastrulation stages10–12. Since cellular context can regulate poly(A) size and function7, we asked if tail length was associated with stability and translation of mRNAs in an intact animal. To do this, we profiled poly(A) tails in Caenorhabditis elegans worms and utilized available datasets to probe for relationships between tail size and gene expression in this organism, as well as in other eukaryotes.

RESULTS

The C. elegans poly(A) profile

Two distinct high-throughput sequencing methods have been developed to assay global poly(A) tail sizes: TAIL-seq8 and PAL-seq (poly(A)-tail length profiling by sequencing)10. We adapted the TAIL-seq protocol to analyze poly(A) tails in C. elegans because it utilizes a standard and direct sequencing platform. However, the TAIL-seq method relies on costly bead-based ribosomal RNA (rRNA) removal procedures that are ineffective or unavailable for many organisms, including C. elegans. Therefore, it was necessary to modify TAIL-seq to minimize contamination by rRNAs. Inspired by the PAL-seq method, we used a splint ligation approach, in which a DNA oligo bridges the last 9 adenosines of the poly(A) tail and the 3’adaptor, greatly favoring the ligation reaction of poly(A)+ RNAs over non-adenylated transcripts (Fig. 1a). This adapted TAIL-seq method produces reliable and reproducible libraries (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c), requires less starting material, and can be readily applied to measure poly(A) tails in any organism. Since our adaptation is very similar to the recently published mTAIL-seq (mRNA-TAIL-seq) method12, we will also refer to it as mTAIL-seq (see Online Methods for our protocol).

Figure 1.

The C. elegans poly(A) profile. (a) Outline of the adapted mTAIL-seq procedure. A splint oligo is used to select for polyadenylated RNAs and exclude other RNA contaminants. (b and c) Global size distribution of C. elegans poly(A) tails measured by mTAIL-seq (b) and bulk poly(A) labeling (c). (d) Distribution of median poly(A) tail-length per gene (n = 13,601 protein coding genes). Genes with a median tail ≤ 70 nt were categorized as short-tailed (n = 3,570), genes with a median tail >70 and ≤ 94 nt were categorized as medium-tailed (n = 6,648) and genes with a median tail > 94 nt were categorized as long-tailed (n = 3,383). (e) Functional annotations (Gene Ontology terms) significantly enriched for genes with short or long tails. The colored bars represent the percent of members in each tail-length category. (f) Tissue enrichment profiles for genes with short, medium or long tails. ▲ significant enrichment; ▼ significant depletion for a tissue category (p<0.01, Fisher test). Poly(A) tail measurements, DAVID Gene Ontology Analysis, and tissue enrichment analysis for C. elegans transcripts are available in Supplementary Data Set 1.

We used mTAIL-seq to investigate the poly(A) tail lengths of transcripts produced during the last larval stage of worm development (L4). We found that 90% of all individual mRNA molecules have tail lengths between 26 and 132 nucleotides (nt) and the median overall poly(A) length is 57 nt (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Data Set 1). These sizes are comparable to the bulk tail lengths measured in mammalian8–10 and Drosophila S2 cells10. Interestingly, the most abundant species of polyadenylated mRNAs were 33–34 nt (Fig. 1b), which is close to the reported 25–30 nt footprint for a single PABP13–15. Additionally, we observed a phasing pattern with peaks at the poly(A) sizes expected to occur with serial binding of PABP (Fig. 1b), suggesting removal of unprotected 3’ adenosines. Furthermore, the sharp drop in frequency of mRNAs with tail-lengths under 30 nt indicates that the minimal tail length required for stability corresponds to the size of one PABP footprint. We validated this phasing pattern with a ~34 nt peak by direct labeling and visualization of bulk poly(A) tails from total C. elegans RNA (Fig. 1c), which was consistent with previous poly(A) profiling of nematode RNA by this method16.

The mTAIL-seq method allowed us to analyze the tail distributions and median tail lengths of 13,601 protein coding gene transcripts with 10 or more poly(A) measurements. Within this comprehensive dataset, the most frequent median poly(A) length was 82 nt, with 90% of mRNAs having median tails ranging between 53 and 115 nt (Fig. 1d). To investigate if there were functional classes of genes that tended to have longer or shorter poly(A) tails, genes were sorted according to their median tail lengths. We classified the quartiles of genes with the shortest (short: ≤ 70 nt) and longest (long: > 94 nt) median poly(A) tails (Fig. 1d) and searched for enriched gene ontology (GO) terms within each category (Supplementary Data Set 1). Short-tailed transcripts were highly enriched for genes involved in translation, nucleosome components, and cuticular collagens (Fig. 1e). Conversely, long-tailed transcripts were enriched for genes with regulatory functions, such as transcription factors, signal transduction proteins, mediators of neuronal activity, and hormone receptors (Fig. 1e). The observation that the long-tailed category was enriched for genes associated with neuronal functions prompted us to investigate the relationship between tissue-specific expression17 and poly(A) length. Remarkably, many long-tailed genes were specific to neurons, whereas short-tailed transcripts were enriched for genes with germline and muscle expression (Fig. 1f). Binning of transcripts based on predicted PABP occupancy produced similar results (Supplementary Fig. 1d–e). For example, 68% of “ribosome” genes have median tail lengths expected to bind 1–2 PABPs.

Highly expressed mRNAs have short poly(A) tails

As shortening of the poly(A) tail is usually associated with mRNA destabilization2,3, we were surprised to find that short-tailed transcripts were enriched on highly expressed genes, such as those encoding ribosomal proteins (Fig. 1e). However, this pattern would explain the disparity between the median tail of the global mRNA pool (57 nt) and the median poly(A) size per transcript (82 nt). Our analyses indicate that the transcripts associated with short tails are very abundant, thus skewing the global poly(A) profile towards shorter poly(A) lengths (Fig. 1b and d). To compare steady state transcript levels to poly(A) size, we plotted the median tail lengths of mRNAs categorized by relative abundance (Fig. 2a). This analysis revealed that the majority of highly expressed transcripts contained short tails, whereas the least abundant transcripts had longer tail distributions. When we binned genes according to median poly(A) tail lengths, we observed a striking inverse correlation between poly(A) size and transcript abundance (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 1). The mRNAs with shorter median poly(A) tail lengths were, on average, much more abundant than those with the longest tails. The only exception was the small group of 33 transcripts with median tails in the 29–35 nt range, where many RNAs likely contain tails too short to accommodate a single PABP and are undergoing active degradation. This strong inverse relationship between tail length and transcript abundance was unexpected, as it is generally thought that longer tails are associated with stable and highly expressed RNAs2,5,7,18.

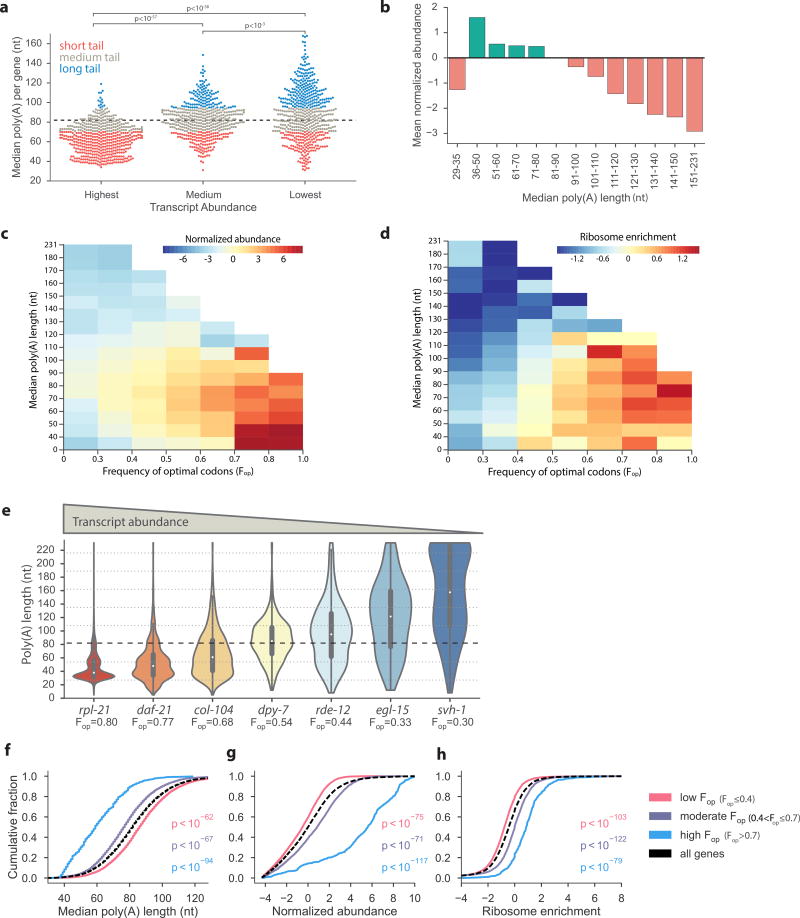

Figure 2.

Highly expressed mRNAs have short poly(A) tails. (a) Tail-length distribution is different in pools of genes with distinct expression levels. The transcript abundance categories represent the highest expressed genes (n = 500), those closest to the median expression (n = 500), and lowest expressed (n = 500). All three distributions were significantly different (Mann-Whitney U test). (b) Global relationship between poly(A) length and abundance was measured by plotting the mean normalized abundance of bins of genes (n = 13,601 protein coding genes) divided by median tail lengths. (c and d) Heat maps demonstrating the interplay of the frequency of optimal codons (Fop) and tail size with transcript abundance (n = 13,421 protein coding genes) (c) and ribosome enrichment25 (n = 13,370 protein coding genes) (d). (e) Violin distribution plots with inlaid box-plots (white dot represents the median) of all tail-length measurements in genes with different frequencies of optimal codons (Fop) and abundance levels. (f to h) C. elegans genes were classified according to codon optimization, demonstrating a significant relationship between translational efficiency and the cumulative distribution of poly(A) length (f), transcript abundance (g) and ribosome enrichment25 (h). Normalized abundance was calculated as the log2 of the fold-change of the number of tags in a transcript over the median transcript level. P-values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test between each codon optimization category and all genes sampled. Poly(A) tail measurements, abundance, Fop, and ribosome enrichment for C. elegans transcripts are available in Supplementary Data Sets 1 and 2.

We next asked if poly(A) tail size was associated with translational efficiency. In general, the ribosome occupancy and frequency of optimal codons in a given mRNA are indicators of its translational status19–21. Additionally, it was recently shown in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Zebrafish that transcripts with optimized codons have higher rates of translational elongation and are more stable than genes with suboptimal codons20,22–24. Consistent with these reports, we found that in C. elegans the most abundant transcripts were enriched for optimal codons (Fig. 2c) and ribosome association (Fig. 2d), using data from previously published ribosome profiling studies25. Moreover, these favored translation substrates were strongly biased towards short poly(A) tails (Fig. 2c–d and Supplementary Date Sets 1 and 2). However, for these genes, and almost all others, we were still able to detect transcripts with tail lengths consistent with the very long (>200 nt) poly(A) tails synthesized on nascent mRNAs1. Specifically, we detected molecules with tail sizes ≥ 200 nt for 78% and ≥ 160 nt for 90% of all genes assayed (Supplementary Fig. 2a). More variability was observed for the minimum and overall range of poly(A) tail sizes of mRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 2b–c). The finding that genes with the highest frequencies of optimal codons were represented by mRNAs that spanned the entire range of detectable tail sizes but were strongly biased for short tailed species (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 2c) suggests that well-expressed mRNAs undergo poly(A) tail shortening to a defined length, which we refer to as pruning.

Examination of the distribution of poly(A) tail lengths for individual genes revealed distinct patterns based on transcript abundance and codon composition (Fig. 2e). For highly expressed and codon-optimized genes such as rpl-21 (a ribosomal protein) and daf-21 (HSP90 - a molecular chaperone), tail lengths ranged from 5–231 nt but concentrated prominently around lengths that would accommodate 1–2 PABPs (~30–60 nt). In contrast, less abundant mRNAs with poorly optimized codons, such as egl-15 (fibroblast growth factor receptor) and svh-1 (neuronal growth factor), tended to have much longer and more diffusely distributed poly(A) tail sizes. On a genome-wide scale, we observed significant differences in the distribution of median poly(A) lengths, abundance and ribosome enrichment for transcripts containing low, medium, and high levels of optimal codons (Fig. 2f–h). Consistent with the general trend of highly expressed genes being compact26, we found that C. elegans genes with short poly(A) tails tended to have short open reading frame (ORF) and 3’ untranslated region (UTR) lengths (Supplementary Table 1).

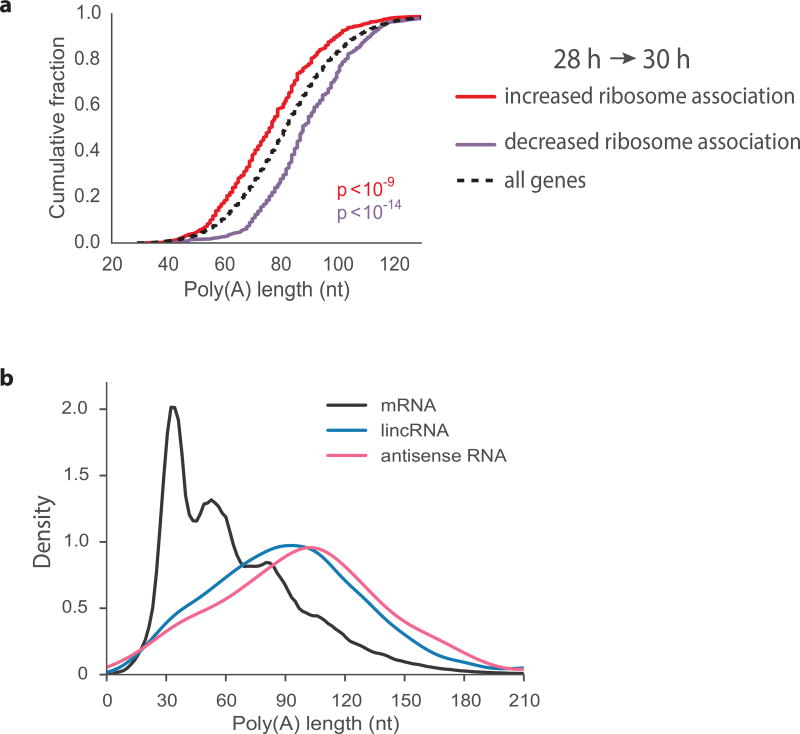

To further investigate the relationship between gene expression and poly(A) tail size, we focused on a set of mRNAs undergoing translational activation or repression during the last larval stage of development, using published RNA-seq and ribosome profiling time course data for C. elegans25. During a two-hour window that spans the time point we used for mTAIL-seq, transcripts for 365 genes become at least 8-fold enriched while those for 341 genes become at least 8-fold depleted from ribosomes, after normalization to changes in mRNA abundance. Remarkably, the ribosome enriched transcripts, and presumably more actively translated group, had significantly shorter median poly(A) tail sizes compared to the transcripts associated with translational repression (Fig. 3a). Further evidence suggesting an inverse relationship between poly(A) tail size and translation surfaced from our analysis of annotated long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs)27. In general, lncRNAs, including antisense RNAs, had long poly(A) tails and showed no evidence of the phasing seen for mRNAs (Fig. 3b). Taken together, our findings suggest that pruned poly(A) tails are a feature of well-translated mRNAs.

Figure 3.

Efficient translation is associated with short poly(A) tails. (a) Cumulative median tail length distributions of genes that are enriched (n = 365) or depleted (n = 341) in ribosomes (at least 8 fold) over a 2 hour period25 that spans the time point used for mTAIL-seq (29 h). P-values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test between each category and all genes sampled. (b) Density plot comparing the bulk distribution of poly(A) tails between mRNAs and two classes of long non-coding RNAs: lincRNAs (long intervening non-coding RNAs) and antisense RNAs. Poly(A) tail measurements are available in Supplementary Data Set 1.

Short poly(A) tails are associated with highly expressed genes across eukaryotes

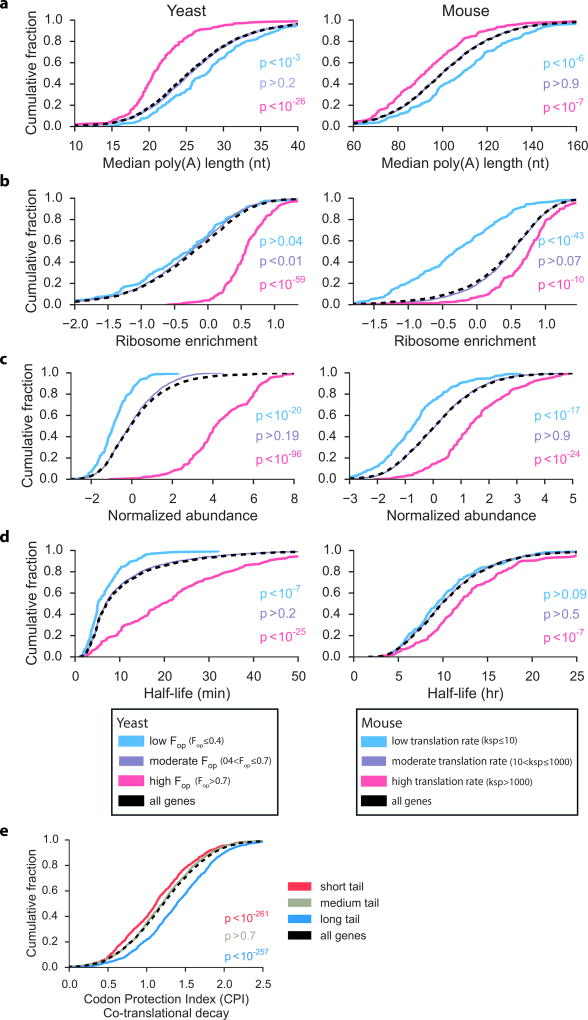

We next asked if the association between mRNA expression and poly(A) tail size might be conserved in other eukaryotes. We analyzed published datasets for poly(A) tail lengths10, ribosome enrichment10, RNA stability20,28,29, and translation29 for S. cerevisiae, Drosophila and mouse transcripts. We observed that highly translated mRNAs tended to have shorter tails (Fig. 4a–b and Supplementary Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 1), higher steady state expression levels (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 1), and longer half-lives (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Table 1). Notably, the shorter relative median tail length of transcripts encoding ribosomal proteins was well conserved among the different organisms (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Additionally, in the C. elegans dataset this class of mRNAs exhibited highly uniform median tail lengths of ~40 nt (Supplementary Fig. 4a), with the largest fraction of tails sized to accommodate one, and to a lesser extent, two PABPs (Supplementary Fig. 4b–c). Overall, these results suggest that pruned poly(A) tails are a feature of stable and efficiently translated mRNAs across species.

Figure 4.

Short poly(A) tails are features of highly expressed mRNAs in yeast and mouse. (a to d) Cumulative distribution plots showing the relationship between translation levels and poly(A) length10 (yeast n = 3,526; mouse n = 3,469) (a), ribosome enrichment10 (yeast n = 3,394; mouse n = 3,214) (b), transcript abundance10 (yeast n = 3,394; mouse n = 3,214) (c), and transcript half-lives (yeast n = 2,702; mouse n = 3,469) (d) in S. cerevisiae20 and mouse NIH3T329 cells. In mouse cells, translation rate constants (ksp) represent the number of proteins synthesized per mRNA per hour29. In yeast, translation rates are reflected in the codon optimization of the transcripts. (e) Relationship between poly(A) tail size and co-translational decay in yeast transcripts (n = 2,994). Higher CPI (Codon Protection Index) values correspond to higher rates of co-translational 5’decapping28. P-values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test between each tail size category (short = 1st quartile; medium = 2nd and 3rd quartiles; long = 4th quartile, based on median length) and all genes sampled. Source data are from refs. 10, 20, 28, 29 and summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Recent studies have shown that codon composition strongly influences mRNA stability and translation efficiency20,22–24. In S. cerevisiae, a series of HIS3 reporters that differ only in their percentages of optimal codons revealed that mRNA half-life is remarkably sensitive to this variable24. Using these same reporters, we analyzed steady state poly(A) tail lengths and observed that transcripts with high percentages of optimal codons accumulated with relatively short poly(A) tails (Supplementary Fig. 5). In contrast, transcripts with lower codon optimality had longer, more diffuse tail sizes (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results suggest that the influence of codon optimality on translation efficiency and mRNA stability extends to poly(A) tail length regulation.

Initially, it was puzzling to find that the class of relatively unstable and poorly translated mRNAs had the longest median poly(A) tail sizes (Figs. 2 and 4). One possibility is that this pool mainly consists of recently synthesized transcripts that have not yet been targeted for rapid decay. In yeast, unstable mRNAs have been shown to undergo rapid deadenylation to a ~10 nt oligo(A) tail length, followed by decapping and 5’ to 3’ exonucleolytic degradation30. Although decay intermediates are rare in wild type cells31,32, a recent study used deep sequencing methods (5PSeq) to identify decapped yeast mRNAs on a genome-wide scale28. Using published 5PSeq datasets for yeast mRNAs28, we found that genes for transcripts with long median tails were represented by the highest levels of 5’ decapped mRNAs (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table 1). The 5’ decay intermediates only accounted for ~12% of cellular RNAs that could be captured by oligo(dT) isolation methods28, which is consistent with the brief existence of decapped RNAs in wild type cells31,32. Thus, many transcripts in the “long” poly(A) tail class may actually be detected in a transient state prior to rapid destabilization. Conversely, most “short” class transcripts seem to be those that accumulate with pruned poly(A) tails.

DISCUSSION

Here we provide genome-wide evidence that short poly(A) tail sizes are a feature of abundant and efficiently translated mRNAs across eukaryotes. Previous poly(A) tail sequencing studies concluded that tail length was not associated with translational efficiency in non-embryonic cells8–10. However, the PAL-seq study reported that in yeast and mouse NIH3T3 cells tail sizes and measures of translation rates were negatively correlated (Rs = −0.12, P<10−9 (S. cerevisiae); Rs = −0.20, P<10−16 (mouse))10, findings confirmed in our analyses (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 1). Additionally, the classes of transcripts found to have long or short tails by our study and PAL-seq10 are largely in agreement, with short-tailed transcripts generally considered to be among the most abundant and well translated in the cell. These observations are also consistent with conclusions from direct labeling experiments where short poly(A) tails were associated with the most stable mRNAs in vegetatively growing Dictyostelium discoideum cells33,34. Presently, it is unclear why other analyses of poly(A) tail size on individual genes in yeast or NIH3T3 cells found that ribosomal protein and other abundantly expressed transcripts had relatively long tails8,35. Those conclusions are at odds with single-gene Northern Blot or PCR based assays that have detected relatively short poly(A) tails on ribosomal protein mRNAs in yeast10,36,37, mouse NIH3T3 cells38, and worms (Supplementary Fig. 4c). It is possible that, like with translation, gene specific control of poly(A) tail length is sensitive to differences in cellular contexts39–41. Furthermore, the categories of “short” and “long” are relative to the population of polyadenylated transcripts analyzed, which was limited in some of the previous studies8,35.

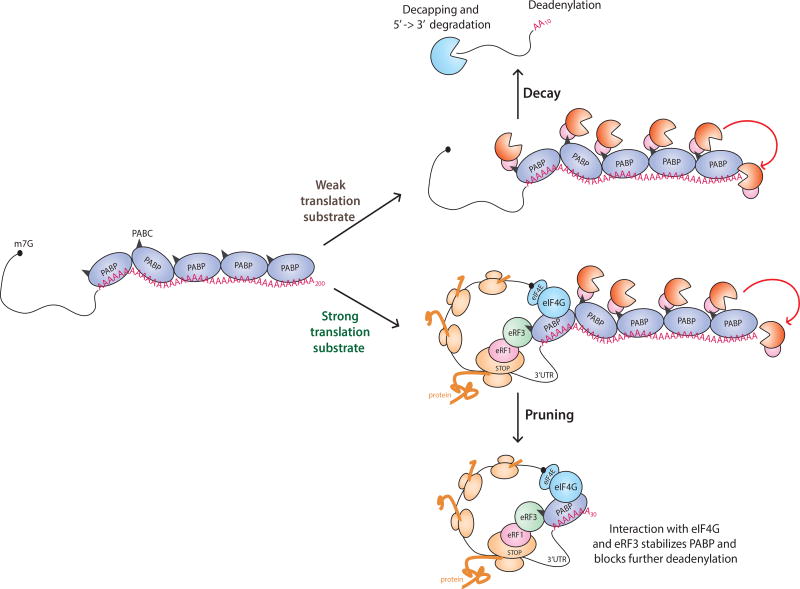

Although our study challenges the longstanding idea that longer tails promote mRNA stability and translation2,5,7,18, it suggests that instead there might be an optimal tail size that results from a shortening process we refer to as pruning. Since poorly translated mRNAs and non-coding transcripts were found to contain long, less defined poly(A) tails, pruning seems to be associated with translational activity. Additionally, bulk and single gene analyses revealed a ~30 nt distribution of poly(A) tail sizes that was primarily associated with highly expressed mRNAs. This phased binding pattern of PABP may be related to translation status and, thus may help distinguish coding from long ncRNAs. The currently available datasets are insufficient for determining if translation directly promotes pruning or stabilizes mRNAs with short poly(A) tails. In a model open to either possibility, the initially long poly(A) tails on newly synthesized transcripts become deadenylated to different extents depending on translational status: for well translated mRNAs, tail shortening ceases at lengths that accommodate a minimal number of PABPs, and for inefficiently translated mRNAs, deadenylation progresses to critically short lengths that trigger decapping and rapid mRNA decay (Fig. 5). Processive deadenylation may result when the last PABP is dislodged from the poly(A) tail, and efficient translation may antagonize this event by stabilizing the PABP-poly(A) tail association, perhaps through direct interactions with initiation (eIF4G) and termination (eRF3) factors1,42. Numerous studies have pointed to dual, seemingly contradictory, roles for PABP in regulating mRNA stability. Whereas binding of PABP can protect the poly(A) tail from degradation43,44, it also has been shown to recruit the major deadenylase complexes PAN2-PAN3 and CCR4-NOT45–47. The multiple PABPs bound to initially long tailed transcripts could engage deadenylation factors that either reduce the tails to lengths that exclude PABP binding, resulting in rapid decay, or that stall at short tail sizes bound by a minimal number of PABPs stably associated with actively translated mRNAs (Fig. 5). While consistent with the well-established connection between translation and mRNA decay3,48, this model implicates an optimal poly(A) tail length that is achieved through translational activity and, in turn, may contribute to the stability and efficient decoding of the mRNA. Overall, our analyses led to the surprising conclusion that in somatic cells short poly(A) tails are a general feature of highly-expressed genes across eukaryotes.

Figure 6.

Model for short poly(A) tails on highly expressed mRNAs. Newly transcribed mRNAs receive long (>200 nt) tails, which are coated with PABP1. The PABP C-terminal domain (PABC, black triangles) binds the CCR4-NOT-Tob and PAN2-3 deadenylation complexes5,6. In strong translation substrates, interactions between a proximal PABP and translation initiation factor eIF4G promote a closed-loop structure and the translation termination factor eRF3 may compete with the deadenylases for binding the PABC domain6,42. These interactions are predicted to stabilize the proximal PABP and prevent processive deadenylation of the transcript, allowing the tail to be pruned to a defined length. Trimming of the poly(A) tail to limit the number of associated PABPs may be important for removing binding sites for factors that catalyze deadenylation and translational repression. For weak translation substrates, the deadenylases recruited to the PABC domain can act processively without the impediment of stabilizing interactions provided by translational activity, resulting in critically short tails that trigger decapping and 5’→3’ degradation of the mRNA.

ONLINE METHODS

Nematode culture and RNA extraction

WT Caenorhabditis elegans (N2 Bristol) animals were cultured on OP50 bacteria at 25°C, and collected at the last larval stage (mid-L4 – 29 h time point). Standard worm synchronization methods were used49. RNA was extracted with Trizol and DNAse treated. RNA quality was measured by 260/280 ratio and confirmed by gel electrophoresis.

Bulk poly(A) labeling

1 µg total RNA (DNase treated) was 3’ labeled by performing a 3’ ligation reaction containing 20 U T4 RNA Ligase (NEB) and 1 µM [32P]pCp (Perkin Elmer) overnight at 16 °C. Enzymes were inactivated at 68 °C for 5 min and unincorporated nucleotides were removed with MicroSpin G-50 columns (GE Healthcare). Labeled RNA was digested with 80 U RNase T1 and 4 ug RNase A (which cannot act on the poly(A) tail) for 2 h at 37 °C; 40 µg unlabeled yeast RNA was used as ballast. The reaction was stopped by Proteinase K digestion of the RNases and the labeled poly(A)s were extracted with acid-phenol:chloroform:IAA and ethanol precipitated. Labeled poly(A) tails were resuspended in 20 µL, of which 5 µL were run on a long 15% Urea-PAGE sequencing gel along with labeled Decade RNA Marker (Ambion). The gel was dried onto whatman paper and scanned on a PhosphorImager.

Poly(A) analysis by northern blot

As detailed in Sallés et al., 199950, total RNA samples were digested with RNase H (NEB) in the presence of a gene specific complementary oligonucleotide and, in the case of poly(A)- samples, also oligo(dT)18. The samples were then resolved on a 6% Urea-PAGE minigel along with RNA Century marker (Ambion) for size determination of the fragments. Northern blotting was performed as described in Van Wynsberghe et al., 201151.

Yeast culture and RNA analysis

RNA samples from strains expressing HIS3 mRNA reporters with varying degrees of codon optimality were prepared and subjected to poly(A) tail length analyses by RNase H Northerns as previously described24,32.

mTAIL-seq

mTAIL-seq was performed as in the original TAIL-seq8, with the following modifications. 3’ adaptor splint ligation: A splint oligonucleotide was used to favor capture of poly(A)+ RNAs. We incubated 20 ug of total RNA in a 5 uL volume with 1 uL 10 uM biotinylated 3’ adaptor and 1 uL 10 uM splint oligonucleotide (5’-NNNGTCAGTTTTTTTTT-3’) at room temperature for 5 min. Next, 1 uL 10× RNA ligase buffer (NEB), 0.5 uL of Superase-In (Ambion) and 1 uL T4 RNA ligase 2 truncated (NEB) were added and the ligation was performed overnight at 18 °C. RNA Size selection: After partially digesting the RNA from the ligation reaction with 2 U of RNase T1 (1U /uL) for 5 min at 22 °C and performing the original protocol for biotin pull-down and on-bead 5’ phosphorylation, we eluted the RNA and size-selected fragments of 250–1000 nt. This was done by gel extraction and purification from a 6% Urea-PAGE gel. Libraries were normalized, pooled and then sequenced in the Illumina MiSeq platform (51 × 251 bp paired end run) with PhiX control library and the spike-in controls mixture. The quantified fluorescent signals were saved and processed by tailseeker2. Since this protocol is very similar to the recently published method, mTAIL-seq12, we refer to our method by the same name.

mTAIL-seq data analysis

Base calling, trimming of adapter sequences, removal of duplicated reads and determination of poly(A) tail sizes were performed by tailseeker2. Reads were analyzed by mapping to the WS247 assembly of the C. elegans genome using RNA-STAR52. Poly(A) lengths were then assigned to individual coding genes by intersecting the mapped sequences with WormBase.org WS247 gene annotations using BEDTools53. Assignment to WormBase annotated non-coding RNAs27 was determined after ruling out matches to other overlapping coding and non-coding transcripts. Sequenced tags without a poly(A) tail were discarded and represented less than 0.02 percent of the data. The minimal poly(A) length detected was 5 nt.

RNA-seq

Three independent replicates of wildtype C. elegans were cultured at 25° and collected at the L4 stage for RNA. These samples were prepared for sequencing by rRNA depletion with Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Mix – Gold (Illumina), and the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina) according to the Low Sample Protocol. After sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq platform, read counts were quantified using kallisto54 and aligned to C. elegans genome WS247.

Frequency of optimal codons (Fop) and ribosome enrichment

Optimal codons have been identified for yeast20, C. elegans55 and D. melanogaster56. Fop was calculated as in a previous study55 and represents the ratio of optimal codons relative to the total number of codons in a transcript, excluding codons for amino acids represented by a single codon (methionine and tryptophan) and stop codons. Values can range from 0 to 1, with a Fop of 1 meaning that every codon is optimal. Ribosome enrichment was determined by calculating the log2 fold change of normalized RPKM values for each transcript in the ribosome fraction relative to total RNA using paired RNA-seq and ribosome profiling datasets10,25. The first 50 nucleotides of the ORF were excluded from this analysis in order to avoid biases at the start codon.

Gene Ontology (GO) and tissue enrichment analysis

GO terms associated with long and short-tailed gene pools were identified using DAVID57. Analysis for tissue enrichment in long and short-tailed genes was performed by employing scores from a dataset of global predictions of tissue-specific gene expression in C. elegans17.

Statistics

Fisher’s exact test was used to test for enrichment in gene classes. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to test for differences in the distribution of values belonging to specific gene categories and all genes tested. Spearman correlations were used to measure the strength and direction of association between two ranked variables.

Data availability

The datasets generated in this study for analyzing poly(A) tail length and RNA expression in L4 stage C. elegans are available on GEO under the accession number GSE104502. Source data for figures 1d–f; 2a–d, f–h; 3a; Supplementary figures 2a–c; 4a; Supplementary Table 1 are available with the paper online. Previously published datasets used in this study are summarized in Supplementary Table 2 and include the following, C. elegans: ribosome profiling and RNA-seq25, ORF and 3’UTR lengths58; S. cerevisiae: poly(A) measurements10, ribosome profiling and RNA-seq10, RNA half-life20, and co-translational 5’ decapping (codon protection index of cycloheximide treated cells)28. NIH3T3: poly(A) measurements10, ribosome profiling and RNA-seq10, RNA half-life29, and translation rates29. Drosophila S2: poly(A) measurements and RNA-seq10. HeLa: poly(A) measurements10. Other data are available upon request. A Life Sciences Reporting Summary for this article is available.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank V.N. Kim, J. Lim, and H. Chang for providing a detailed TAIL-seq protocol, their algorithm (tailseeker2), and technical assistance; E. Van Nostrand and members of the Yeo lab for assistance with the Illumina MiSeq platform; J. Chen and J. Broughton for programming support; J. Lykke-Andersen, H. Cook-Andersen, M. Wilkinson and members of the Pasquinelli lab for suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript. L.B.C. and A.L.N. were supported by the UCSD Cellular and Molecular Genetics Training Program through an institutional grant from the National Institute of General Medicine (T32 GM007240) and NSF Graduate Research Fellowships DGE-1650112 (L.B.C.) and DGE-1650112 (A.L.N.). This work was supported by grants from the NIH (GM071654) and UCSD Academic Senate to A.E.P.; NIH (GM118018) to J.C; NIH (HG004659) to G.W.Y.; S.A.L. is an international HHMI predoctoral fellow.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.E.P. and S.A.L. designed the project and wrote the paper. S.A.L. conducted the experiments and data analysis with help from L.B.C., A.L.N., B.A.Y. and G.W.Y. Y.H.C and J.C. designed and performed experiments for Supp FIG 5.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Mangus DA, Evans MC, Jacobson A. Poly(A)-binding proteins: multifunctional scaffolds for the post-transcriptional control of gene expression. Genome Biol. 2003;4:223. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-7-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstrohm AC, Wickens M. Multifunctional deadenylase complexes diversify mRNA control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:337–44. doi: 10.1038/nrm2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roy B, Jacobson A. The intimate relationships of mRNA decay and translation. Trends Genet. 2013;29:691–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonas S, Izaurralde E. Towards a molecular understanding of microRNA-mediated gene silencing. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:421–33. doi: 10.1038/nrg3965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wahle E, Winkler GS. RNA decay machines: deadenylation by the Ccr4-not and Pan2-Pan3 complexes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829:561–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie J, Kozlov G, Gehring K. The "tale" of poly(A) binding protein: the MLLE domain and PAM2-containing proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:1062–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weill L, Belloc E, Bava FA, Mendez R. Translational control by changes in poly(A) tail length: recycling mRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:577–85. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang H, Lim J, Ha M, Kim VN. TAIL-seq: genome-wide determination of poly(A) tail length and 3' end modifications. Mol Cell. 2014;53:1044–52. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park JE, Yi H, Kim Y, Chang H, Kim VN. Regulation of Poly(A) Tail and Translation during the Somatic Cell Cycle. Mol Cell. 2016;62:462–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subtelny AO, Eichhorn SW, Chen GR, Sive H, Bartel DP. Poly(A)-tail profiling reveals an embryonic switch in translational control. Nature. 2014;508:66–71. doi: 10.1038/nature13007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eichhorn SW, et al. mRNA poly(A)-tail changes specified by deadenylation broadly reshape translation in Drosophila oocytes and early embryos. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.16955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim J, Lee M, Son A, Chang H, Kim VN. mTAIL-seq reveals dynamic poly(A) tail regulation in oocyte-to-embryo development. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1671–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.284802.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baer BW, Kornberg RD. The protein responsible for the repeating structure of cytoplasmic poly(A)-ribonucleoprotein. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:717–21. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith BL, Gallie DR, Le H, Hansma PK. Visualization of poly(A)-binding protein complex formation with poly(A) RNA using atomic force microscopy. J Struct Biol. 1997;119:109–17. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Z, Day N, Trifillis P, Kiledjian M. An mRNA stability complex functions with poly(A)-binding protein to stabilize mRNA in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4552–60. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nousch M, Techritz N, Hampel D, Millonigg S, Eckmann CR. The Ccr4-Not deadenylase complex constitutes the main poly(A) removal activity in C. elegans. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:4274–85. doi: 10.1242/jcs.132936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chikina MD, Huttenhower C, Murphy CT, Troyanskaya OG. Global prediction of tissue-specific gene expression and context-dependent gene networks in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jalkanen AL, Coleman SJ, Wilusz J. Determinants and implications of mRNA poly(A) tail size--does this protein make my tail look big? Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;34:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingolia NT. Ribosome profiling: new views of translation, from single codons to genome scale. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:205–13. doi: 10.1038/nrg3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Presnyak V, et al. Codon optimality is a major determinant of mRNA stability. Cell. 2015;160:1111–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quax TE, Claassens NJ, Soll D, van der Oost J. Codon Bias as a Means to Fine-Tune Gene Expression. Mol Cell. 2015;59:149–61. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bazzini AA, et al. Codon identity regulates mRNA stability and translation efficiency during the maternal-to-zygotic transition. EMBO J. 2016;35:2087–2103. doi: 10.15252/embj.201694699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishima Y, Tomari Y. Codon Usage and 3' UTR Length Determine Maternal mRNA Stability in Zebrafish. Mol Cell. 2016;61:874–85. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radhakrishnan A, et al. The DEAD-Box Protein Dhh1p Couples mRNA Decay and Translation by Monitoring Codon Optimality. Cell. 2016;167:122–132 e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendriks GJ, Gaidatzis D, Aeschimann F, Grosshans H. Extensive oscillatory gene expression during C. elegans larval development. Mol Cell. 2014;53:380–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson MK, Gilbert WV. mRNA length-sensing in eukaryotic translation: reconsidering the "closed loop" and its implications for translational control. Curr Genet. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00294-016-0674-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nam JW, Bartel DP. Long noncoding RNAs in C. elegans. Genome Res. 2012;22:2529–40. doi: 10.1101/gr.140475.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelechano V, Wei W, Steinmetz LM. Widespread Co-translational RNA Decay Reveals Ribosome Dynamics. Cell. 2015;161:1400–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwanhausser B, et al. Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature. 2011;473:337–42. doi: 10.1038/nature10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coller J, Parker R. Eukaryotic mRNA decapping. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:861–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu CL, Stevens A. Yeast cells lacking 5'-->3' exoribonuclease 1 contain mRNA species that are poly(A) deficient and partially lack the 5' cap structure. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4826–35. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu W, Sweet TJ, Chamnongpol S, Baker KE, Coller J. Co-translational mRNA decay in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2009;461:225–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palatnik CM, Storti RV, Capone AK, Jacobson A. Messenger RNA stability in Dictyostelium discoideum: does poly(A) have a regulatory role? J Mol Biol. 1980;141:99–118. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palatnik CM, Storti RV, Jacobson A. Fractionation and functional analysis of newly synthesized and decaying messenger RNAs from vegetative cells of Dictyostelium discoideum. J Mol Biol. 1979;128:371–95. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beilharz TH, Preiss T. Widespread use of poly(A) tail length control to accentuate expression of the yeast transcriptome. RNA. 2007;13:982–97. doi: 10.1261/rna.569407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown CE, Sachs AB. Poly(A) tail length control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae occurs by message-specific deadenylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6548–59. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tucker M, et al. The transcription factor associated Ccr4 and Caf1 proteins are components of the major cytoplasmic mRNA deadenylase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. 2001;104:377–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong YY, et al. Cordycepin inhibits protein synthesis and cell adhesion through effects on signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:2610–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.071159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gowrishankar G, et al. Inhibition of mRNA deadenylation and degradation by different types of cell stress. Biol Chem. 2006;387:323–7. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hilgers V, Teixeira D, Parker R. Translation-independent inhibition of mRNA deadenylation during stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA. 2006;12:1835–45. doi: 10.1261/rna.241006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kleene KC, Cataldo L, Mastrangelo MA, Tagne JB. Alternative patterns of transcription and translation of the ribosomal protein L32 mRNA in somatic and spermatogenic cells in mice. Exp Cell Res. 2003;291:101–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoshino S. Mechanism of the initiation of mRNA decay: role of eRF3 family G proteins. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2012;3:743–57. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coller JM, Gray NK, Wickens MP. mRNA stabilization by poly(A) binding protein is independent of poly(A) and requires translation. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3226–35. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Decker CJ, Parker R. A turnover pathway for both stable and unstable mRNAs in yeast: evidence for a requirement for deadenylation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1632–43. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.8.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ezzeddine N, et al. Human TOB, an antiproliferative transcription factor, is a poly(A)-binding protein-dependent positive regulator of cytoplasmic mRNA deadenylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7791–801. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01254-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Funakoshi Y, et al. Mechanism of mRNA deadenylation: evidence for a molecular interplay between translation termination factor eRF3 and mRNA deadenylases. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3135–48. doi: 10.1101/gad.1597707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siddiqui N, et al. Poly(A) nuclease interacts with the C-terminal domain of polyadenylate-binding protein domain from poly(A)-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25067–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shoemaker CJ, Green R. Translation drives mRNA quality control. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:594–601. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Porta-de-la-Riva M, Fontrodona L, Villanueva A, Ceron J. Basic Caenorhabditis elegans methods: synchronization and observation. J Vis Exp. 2012:e4019. doi: 10.3791/4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salles FJ, Richards WG, Strickland S. Assaying the polyadenylation state of mRNAs. Methods. 1999;17:38–45. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Wynsberghe PM, Chan SP, Slack FJ, Pasquinelli AE. Analysis of microRNA expression and function. Methods Cell Biol. 2011;106:219–52. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-544172-8.00008-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:841–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, Pachter L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:525–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stenico M, Lloyd AT, Sharp PM. Codon usage in Caenorhabditis elegans: delineation of translational selection and mutational biases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2437–46. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.13.2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akashi H. Synonymous codon usage in Drosophila melanogaster: natural selection and translational accuracy. Genetics. 1994;136:927–35. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Contrino S, et al. modMine: flexible access to modENCODE data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1082–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated in this study for analyzing poly(A) tail length and RNA expression in L4 stage C. elegans are available on GEO under the accession number GSE104502. Source data for figures 1d–f; 2a–d, f–h; 3a; Supplementary figures 2a–c; 4a; Supplementary Table 1 are available with the paper online. Previously published datasets used in this study are summarized in Supplementary Table 2 and include the following, C. elegans: ribosome profiling and RNA-seq25, ORF and 3’UTR lengths58; S. cerevisiae: poly(A) measurements10, ribosome profiling and RNA-seq10, RNA half-life20, and co-translational 5’ decapping (codon protection index of cycloheximide treated cells)28. NIH3T3: poly(A) measurements10, ribosome profiling and RNA-seq10, RNA half-life29, and translation rates29. Drosophila S2: poly(A) measurements and RNA-seq10. HeLa: poly(A) measurements10. Other data are available upon request. A Life Sciences Reporting Summary for this article is available.