Significance

The ethylene signaling pathway has been extensively investigated in Arabidopsis, and EIN2 is the central component. Rice is a monocotyledonous model plant that exhibits different features in many aspects compared with the dicotyledonous Arabidopsis. Thus, rice provides an alternative system for identification of novel components of ethylene signaling. In this study, we identified a stabilizer of OsEIN2 through analysis of the rice ethylene-insensitive mutant mhz3. We found that MHZ3 stabilizes OsEIN2 likely by binding to its Nramp-like transmembrane domain and impeding protein ubiquitination, blocking proteasome-mediated protein degradation. This study reveals that MHZ3 is required for ethylene signaling and identifies how MHZ3 binds to OsEIN2 via the OsEIN2 N-terminal Nramp-like domain.

Keywords: ethylene, protein stabilization, protein–protein interaction, rice

Abstract

The phytohormone ethylene regulates many aspects of plant growth and development. EIN2 is the central regulator of ethylene signaling, and its turnover is crucial for triggering ethylene responses. Here, we identified a stabilizer of OsEIN2 through analysis of the rice ethylene-response mutant mhz3. Loss-of-function mutations lead to ethylene insensitivity in etiolated rice seedlings. MHZ3 encodes a previously uncharacterized membrane protein localized to the endoplasmic reticulum. Ethylene induces MHZ3 gene and protein expression. Genetically, MHZ3 acts at the OsEIN2 level in the signaling pathway. MHZ3 physically interacts with OsEIN2, and both the N- and C-termini of MHZ3 specifically associate with the OsEIN2 Nramp-like domain. Loss of mhz3 function reduces OsEIN2 abundance and attenuates ethylene-induced OsEIN2 accumulation, whereas MHZ3 overexpression elevates the abundance of both wild-type and mutated OsEIN2 proteins, suggesting that MHZ3 is required for proper accumulation of OsEIN2 protein. The association of MHZ3 with the Nramp-like domain is crucial for OsEIN2 accumulation, demonstrating the significance of the OsEIN2 transmembrane domains in ethylene signaling. Moreover, MHZ3 negatively modulates OsEIN2 ubiquitination, protecting OsEIN2 from proteasome-mediated degradation. Together, these results suggest that ethylene-induced MHZ3 stabilizes OsEIN2 likely by binding to its Nramp-like domain and impeding protein ubiquitination to facilitate ethylene signal transduction. Our findings provide insight into the mechanisms of ethylene signaling.

The phytohormone ethylene regulates multiple aspects of plant growth and development. A linear signaling pathway has been established based on extensive studies in Arabidopsis (1). Ethylene is perceived by a family of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane-bound receptors (2–5). The signal is transmitted through the negative regulator CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE RESPONSE 1 (CTR1) (6) and then the positive regulator ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE 2 (EIN2) (7) and is further amplified via the master transcription factor EIN3 and EIN3-LIKE1 (EIL1)-mediated transcription cascades, which ultimately activate a great deal of ethylene-responsive genes (8–10).

EIN2 is the essential regulator of the ethylene response (7). The N terminus of EIN2 consists of 12 predicted transmembrane helices that show sequence similarity to the Nramp family of metal transporters, and its C terminus has a large hydrophilic domain (7). EIN2 is predominantly localized to the ER (11). In the absence of ethylene, the receptors negatively regulate ethylene responses by activating downstream CTR1 (12). The Raf-like Ser/Thr kinase CTR1 directly phosphorylates EIN2 to prevent it from signaling (13). F-box proteins EIN2-TARGETING PROTEIN1 (ETP1) and ETP2 interact with the EIN2 C terminus and target the protein for proteasome-mediated degradation (14). In the presence of ethylene, unphosphorylated EIN2 undergoes proteolytic cleavage, and the cytosolic C-terminal domain is translocated into the nucleus (13, 15, 16). In the nuclei, EIN2 directly regulates histone acetylation to facilitate EIN3 binding to its target genes (17, 18). Interestingly, the EIN2 C-terminal domain can also be transferred into the P-body to mediate translational repression of EIN3-BINDING F-BOX PROTEIN1 (EBF1) and EBF2 (19, 20), which target EIN3/EIL1 for degradation in the absence of ethylene (21, 22). Extensive studies have elucidated how EIN2 activates downstream signaling through its C-terminal domain; however, the significance of the N-terminal Nramp-like domain is largely unknown.

Rice (Oryza sativa) is a monocotyledonous model plant. In comparison with Arabidopsis, rice exhibits different features in many aspects such as plant structure, living environment, growth and developmental process, and ethylene responses (23). Importantly, rice has limited synteny with Arabidopsis at the genome level (24). These facts suggest that rice can be used as an alternative system for the identification of novel components of ethylene signaling. We have developed a mutant screening system in rice and isolated a set of ethylene-response mutants (25–30). In this study, we characterized the ethylene-insensitive mhz3 mutant. MHZ3 encodes a previously uncharacterized ER membrane protein that genetically acts on and physically interacts with OsEIN2. MHZ3 associates with the OsEIN2 Nramp-like domain to stabilize the protein by inhibiting ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation. Our findings reveal a potential mechanism by which EIN2 transduces ethylene signals via its N-terminal Nramp-like domain.

Results

Phenotypic Analysis and Gene Identification of mhz3 Mutant.

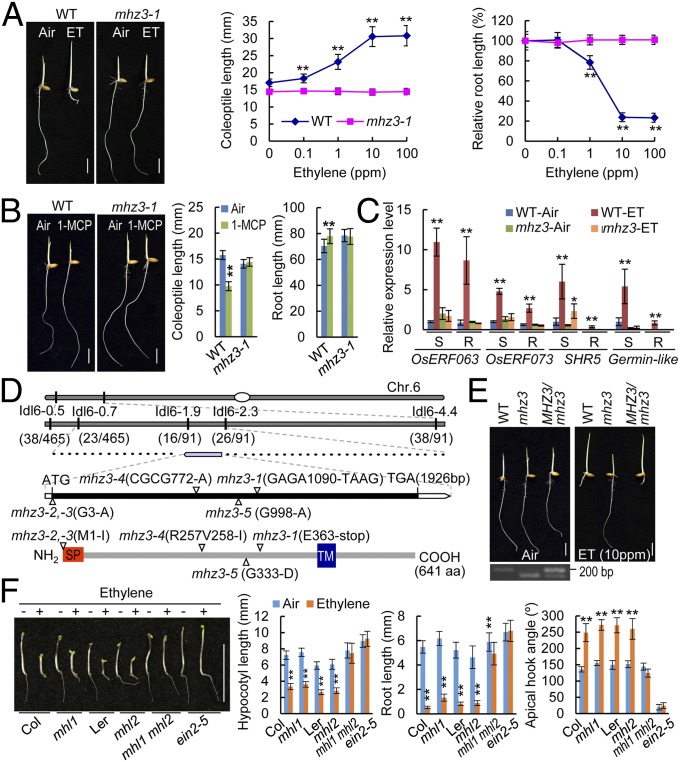

Five allelic mhz3 mutants (mhz3-1 to mhz3-5) were previously identified in our genetic screen for rice ethylene-response mutants (25). Ethylene treatment inhibited root growth but promoted coleoptile elongation in dark-grown wild-type (WT) rice seedlings (Fig. 1A). By contrast, the effects of ethylene on coleoptile and root growth of etiolated rice seedlings are almost completely blocked by the mhz3 mutation (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B). Treatment with 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP), an inhibitor of ethylene perception, reduced coleoptile length and increased root length in WT seedlings due to repression of the activity of endogenous ethylene. However, 1-MCP treatment has no effects on mhz3 seedlings (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that mhz3 is insensitive to both endogenous and exogenous ethylene. The ethylene responsiveness of mhz3 was further confirmed at the molecular level by examining the expression of ethylene-inducible genes, and ethylene induction of the genes was abolished or hampered in the mhz3 mutant (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic analysis and gene identification of mhz3. (A) Ethylene-response phenotype of mhz3. Etiolated seedlings were treated with various concentrations of ethylene for 3 d. Representative seedlings grown in the air and in 10 ppm ethylene (ET) are shown (Left). Coleoptile (Center) and root lengths (Right) are means ± SD, n > 30 (**P < 0.01; Student’s t test; compared with 0 ppm). (B) mhz3 is insensitive to 1-MCP. (Left) Etiolated seedlings were treated with 10 ppm 1-MCP or without (Air) for 3 d. Coleoptile (Center) and root lengths (Right) are means ± SD (n > 30). Asterisks indicate significant difference between Air and 1-MCP (P < 0.01; Student’s t test). (C) Ethylene-induced gene expression is abolished in mhz3. Total RNAs from etiolated 2-d-old seedlings treated with 10 ppm ethylene or without (Air) for 8 h were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis. Data are means ± SD, n = 3 (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; Student’s t test; compared with Air). R, root; S, shoot. (D) Map-based cloning of MHZ3. The mutation sites are indicated in schematic diagrams. (E) Functional complementation of mhz3-1 with WT MHZ3 genomic DNA (Upper). (Lower Left) Confirmation of the transgene by PCR. (F) Triple response of mhl1 mhl2 double mutant of Arabidopsis. (Left) Etiolated seedlings were treated with (+) or without (−) 10 ppm ethylene for 4 d. (Right) Data are means ± SD, n > 15 (P < 0.01; Student’s t test; compared with “Air”). (A, B, E, and F scale bars, 10 mm.)

The MHZ3 gene was identified by map-based cloning. All mhz3 mutants harbored a mutation at the LOC_Os06g02480 locus (Fig. 1D). The mutation sites were further confirmed by PCR-based analysis using cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) or derived CAPS primers (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). Genetic transformation with the WT genomic DNA fragment rescued the ethylene-insensitive phenotype of mhz3-1 (Fig. 1E). The results convincingly demonstrate that MHZ3 is located at the LOC_Os06g02480 locus. Gene expression and promoter-GUS analyses revealed that MHZ3 is universally expressed in the rice organs examined from vegetative to reproductive stages (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The deduced MHZ3 protein has no domains of known function, except for a signal peptide (SP) and one transmembrane helix (TM) (Fig. 1D). BLAST search and phylogenetic analysis revealed that MHZ3 belongs to a previously uncharacterized plant-specific gene family that is distributed from algae to land plants (SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S4). Ortholog search in the Rice Genome Annotation Project database (rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/) reveals that MHZ3 is a single-copy gene in the rice genome but has two copies in the Arabidopsis genome. We named these Arabidopsis homologous genes MHZ3-Like1 (MHL1, At1g75140) and MHL2 (At1g19370), which share 40% and 38% identity with MHZ3, respectively. Although the mhl1 and mhl2 single mutants exhibited WT-like ethylene response likely due to functional redundancy, the mhl1 mhl2 double mutant displayed ethylene-insensitive phenotype, indicating that MHL1 and MHL2 are required for ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis (Fig. 1F and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A–C). However, it appears that the ethylene-insensitive phenotype of the double mutant is weak compared with that of ein2-5 mutant, suggesting that the function of MHZ3-like genes may not be as strong as that of EIN2 in ethylene signaling.

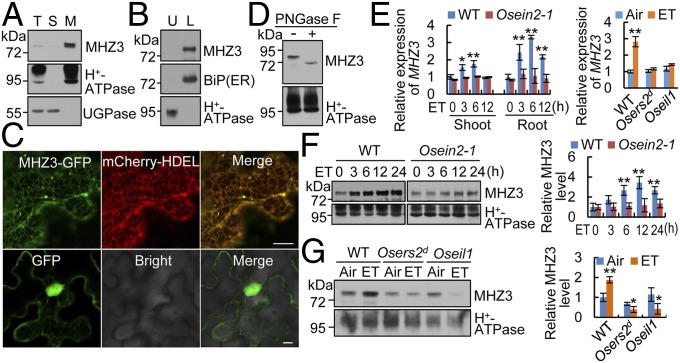

MHZ3 Is an ER-Localized Glycosylated Membrane Protein.

We generated a specific anti-MHZ3 antibody for detecting the endogenous protein. Total proteins of WT seedlings were separated into soluble and microsomal fractions by ultracentrifugation. MHZ3 was mainly detected in the microsomal fraction, indicating that MHZ3 is a membrane-bound protein (Fig. 2A). The microsomal membranes were further separated into plasma membrane (upper phase) and endomembrane systems (lower phase) by aqueous two-phase partitioning. MHZ3 was solely detected in the lower phase, indicating an endomembrane localization of MHZ3 (Fig. 2B). To further determine the subcellular localization, we transiently expressed MHZ3-GFP in tobacco leaf cells. GFP fluorescence was mainly detected in a reticular network-like structure that is labeled by the ER marker protein mCherry-HDEL, suggesting that MHZ3 is predominantly localized at the ER (Fig. 2C). In addition, we observed fluorescent signals in distinct dots along with the ER networks (Fig. 2C), implying that MHZ3 may also target to organelles/compartments other than the ER. Its localization outside the ER may suggest that MHZ3 has additional functions in ethylene signaling and/or in other processes. The MHZ3 protein is predicted to contain three potential N-glycosylation sites, and two of these are conserved in all species (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Deglycosylation assay detected N-glycosylation modification of MHZ3 (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

MHZ3 is an ER-localized glycosylated membrane protein, and its expression is induced by ethylene. (A) Membrane association of MHZ3. Equal amounts of total protein (T), soluble protein (S), and microsomal membranes (M) were immunoblotted for MHZ3, H+-ATPase (plasma membrane marker), and UGPase (cytoplasm marker). (B) Endomembrane association of MHZ3. Microsomal membranes were separated into plasma membrane (upper phase; U) and endomembrane (lower phase; L) systems and then immunoblotted for MHZ3, BiP, and H+-ATPase. (C) ER localization of MHZ3 as revealed by transient expression of MHZ3-GFP in tobacco leaf epidermal cells. mCherry-HDEL is used as an ER marker. GFP is used as a control. (Scale bars, 10 µm.) (D) Deglycosylation assay of MHZ3 using PNGase F. (E) MHZ3 transcript level is induced by 10 ppm ethylene (ET) as revealed by qRT-PCR analysis. Data are means ± SD, n = 3 [*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; Student’s t test; compared with 0 h (Left) or Air (Right)]. (F and G) MHZ3 protein level is induced by ethylene, but the induction is impaired in ethylene-insensitive mutants. (Left) Membrane proteins isolated from rice shoots (F) or roots (G) of etiolated seedlings were immunoblotted for MHZ3 and H+-ATPase (loading control). (Right) Statistical analysis of the relative MHZ3 levels from three independent replicates is presented, and the data are means ± SD, n = 3 [*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; Student’s t test; compared with 0 h (F) or Air (G)].

MHZ3 Expression Is Induced by Ethylene, and the Gene Overexpression Confers Ethylene Hypersensitivity.

We examined MHZ3 gene expression in response to ethylene. The transcript level of MHZ3 was significantly induced by ethylene treatment in both shoots and roots of etiolated WT seedlings, whereas the induction was largely blocked in Osein2-1, Osers2d (a dominant ethylene receptor gain-of-function mutation), and Oseil1 seedlings (Fig. 2E). In Arabidopsis, the transcript level of MHL2 was also significantly induced by ethylene, whereas MHL1 expression was unaffected by ethylene treatment (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D). The protein level of MHZ3 increased steadily upon ethylene treatment (Fig. 2F). However, the ethylene-induced accumulation of MHZ3 protein was completely abolished in Osers2d, Osein2-1, and Oseil1 mutants (Fig. 2 F and G). These results suggest that MHZ3 expression is induced by ethylene at both transcriptional and protein levels and that the induction requires an intact ethylene signaling pathway. Notably, ethylene treatment significantly reduced the MHZ3 level in Osers2d and Oseil1 mutants. This may be due to the depletion of basal MHZ3 protein in stabilizing OsEIN2 (as revealed in the following sections) in the presence of ethylene. Furthermore, we examined MHZ3 localization under ethylene treatment and in Osein2 null backgrounds. Introduction of 35S:MHZ3-GFP into mhz3-1 plants rescued the mutant phenotype, indicating that GFP tagging does not affect MHZ3 function (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). The localization pattern of MHZ3 as revealed by GFP fluorescence is not altered upon ethylene treatment (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). The 35S:MHZ3-GFP and 35S:mCherry-HDEL constructs were cotransformed into rice protoplasts of Osein2 null mutants, and the OsEIN2 mutations did not affect MHZ3 localization (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C).

Next, we overexpressed MHZ3 in WT rice plants to study gene function (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A and B). Compared with the WT and low-expression line (OX26), the high-expression lines (OX21, OX22, and OX24) exhibited slightly but significantly longer coleoptiles and shorter roots when grown in the air and displayed strong inhibition of root growth upon ethylene treatment (SI Appendix, Fig. S7C). 1-MCP treatment only partially reduced the constitutive ethylene response of MHZ3-OX lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S7C). The results suggest that MHZ3 overexpression confers ethylene hypersensitivity in etiolated rice seedlings. At adult stages, MHZ3 overexpression altered some important agricultural traits including reduction of plant height, promotion of leaf senescence, and enhancement of grain size and grain weight (SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

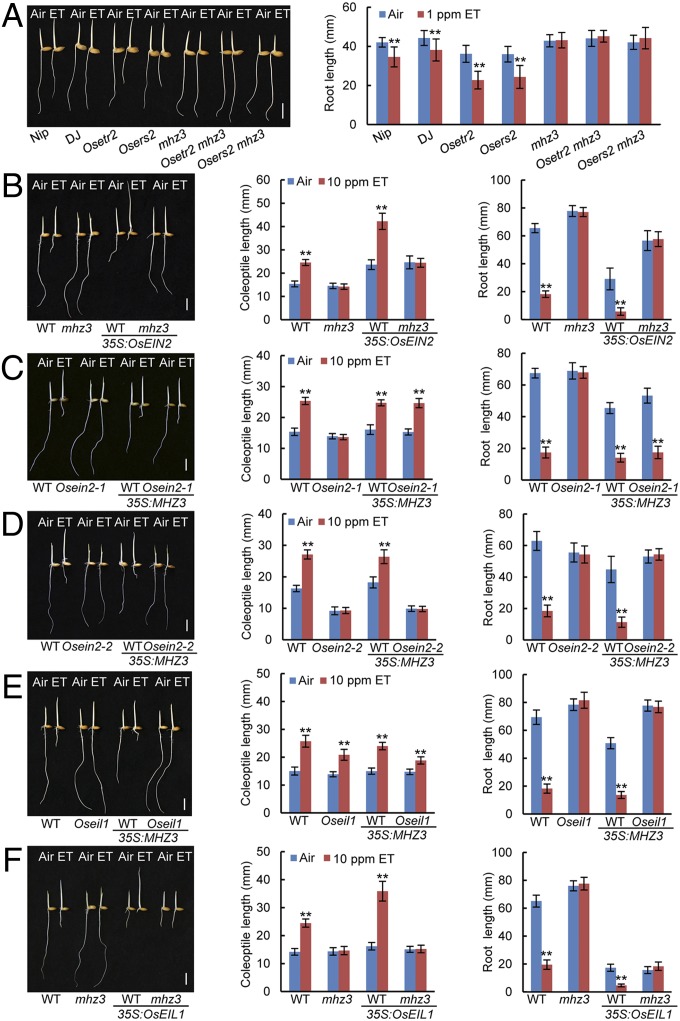

MHZ3 Genetically Acts at OsEIN2.

Genetic analyses were performed to position MHZ3 in the ethylene signaling pathway. Double-mutant analysis showed that ethylene hypersensitivity in the roots of Osetr2 and Osers2 ethylene-receptor loss-of-function mutants was completely abolished by mhz3 mutation, indicating that MHZ3 may act at or downstream of ethylene receptors (Fig. 3A). To examine the epistatic relationship between MHZ3 and CTR1, we constructed the mhl1 mhl2 ctr1 triple mutant of Arabidopsis. The constitutive signaling caused by ctr1 mutation was fully suppressed by mhl1 mhl2 double knockout, implying that MHZ3 may act at or downstream of ctr1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Next, we examined the genetic interaction between MHZ3 and OsEIN2. Overexpression of OsEIN2 in WT seedlings resulted in strong constitutive and enhanced ethylene responses (Fig. 3B) (25). In contrast, OsEIN2 overexpression in mhz3 background led to a weak constitutive ethylene response in the air, but no further response to ethylene treatment (Fig. 3B). The results reveal that the effect of OsEIN2 on rice ethylene response depends on MHZ3 function, suggesting that MHZ3 may act at or downstream of OsEIN2. We previously identified two types of mhz7/Osein2 allelic mutants (25). Osein2-1 harbors an 8-aa-deletion in the loop 2 located between the second and third transmembrane helices in the Nramp-like domain, and Osein2-2 contains a premature stop codon in the nuclear localization signal located at the C-terminal end (25). Interestingly, overexpression of MHZ3 in Osein2-1 fully suppressed its ethylene insensitivity (Fig. 3C). However, MHZ3 overexpression in Osein2-2 was unable to suppress the mutant phenotype (Fig. 3D). Together, these results suggest that MHZ3 likely acts at the OsEIN2 level in the signaling pathway. Next, we further examined the epistatic relationship between MHZ3 and OsEIL1, which mainly regulates rice root ethylene responses as previously identified (26). Overexpression of MHZ3 in Oseil1 was unable to rescue the mutant phenotype (Fig. 3E). In contrast, overexpression of OsEIL1 in mhz3 led to strong inhibition of root growth in the absence of ethylene, which was indistinguishable from that conferred by OsEIL1 overexpression in WT (Fig. 3F). These results indicate that MHZ3 likely functions upstream of OsEIL1. On the other hand, in the presence of ethylene, the 35S:OsEIL1/mhz3 seedlings did not show any further ethylene response relative to the seedlings of 35S:OsEIL1/WT, which exhibited shorter roots and longer coleoptiles upon ethylene treatment (Fig. 3F), indicating that MHZ3 is required for ethylene-induced OsEIL1 activity. Considering the fact that ethylene-induced EIN3/EIl1 stabilization fully relies on the presence of the upstream EIN2 protein (31), our observations agree that MHZ3 works at the OsEIN2 level to modulate OsEIL1 activity.

Fig. 3.

MHZ3 genetically acts at OsEIN2 in ethylene signaling pathway. (A) Ethylene hypersensitivity caused by Osetr2 and Osers2 loss-of-function mutations is fully suppressed by mhz3. (Left) Etiolated seedlings were grown in the air or 1 ppm ethylene (ET) for 2 d. (Right) Root lengths were means ± SD, n = 30 (**P < 0.01; Student’s t test; compared with Air). DJ, Dongjin; Nip, Nipponbare. (B) OsEIN2 overexpression could not restore the ethylene response of mhz3. (Left) Etiolated seedlings were grown in the air or 10 ppm ethylene for 3 d. Coleoptile (Center) and root lengths (Right) are means ± SD, n > 30 (**P < 0.01; Student’s t test; compared with Air). The ethylene response assays were the same in B–F. (C) Overexpression of MHZ3 in Osein2-1 rescued the mutant phenotype. (D) Overexpression of MHZ3 in Osein2-2 could not rescue the mutant phenotype. (E) Overexpression of MHZ3 in Oseil1 could not rescue the mutant phenotype. (F) Overexpression of OsEIL1 in mhz3 results in constitutive ethylene response, but no further response to ethylene treatment. (Scale bars, 10 mm.)

To further validate the genetic relationship between MHZ3 and OsEIN2, we compared their downstream ethylene-response genes (ERGs) identified by RNA-seq analysis (National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive, accession no. SRP041468). In rice shoots, 97.2% (3,702) of MHZ3-dependent ERGs were regulated by OsEIN2; in the roots, 81.5% (682) of MHZ3-dependent ERGs were regulated by OsEIN2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). The results indicate that MHZ3 and OsEIN2 regulate a similar subset of downstream ERGs. Collectively, genetic analyses demonstrate that MHZ3 likely acts at the OsEIN2 level in the signaling pathway.

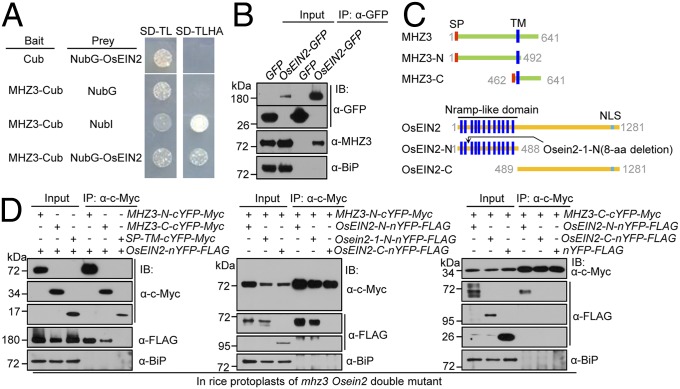

MHZ3 Physically Interacts with OsEIN2 via Association with Its N-Terminal Nramp-Like Domain.

InterPro Domain Scan (www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) analysis revealed that the N terminus of MHZ3 has a domain (amino acids 139 to 458) belonging to a seven-bladed WD β-propeller superfamily that facilitates protein binding, implying that MHZ3 may function through protein–protein interaction. To test this possibility, we performed a membrane-based yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay to examine the interaction of MHZ3 with OsEIN2. In comparison with the negative controls coexpressing the bait or prey with empty vectors, the yeast cells coexpressing MHZ3-Cub and NubG-OsEIN2 were able to grow on the selective media (Fig. 4A), suggesting that MHZ3 can directly interact with OsEIN2 in yeast cells. To validate the protein–protein interaction, we performed a coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay in transgenic rice plants stably expressing OsEIN2-GFP. MHZ3 protein was strongly coimmunoprecipitated by OsEIN2-GFP, but not by the GFP tag, suggesting that MHZ3 associates with OsEIN2 in planta (Fig. 4B). The MHZ3–OsEIN2 interaction was further confirmed using bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays in tobacco leaf epidermal cells and in rice protoplasts (SI Appendix, Fig. S11).

Fig. 4.

MHZ3 physically interacts with OsEIN2 through association with its N-terminal Nramp-like domain. (A) Split-ubiquitin Y2H assay for interaction of MHZ3 and OsEIN2. NubI is the WT N-terminal half of ubiquitin and serves as positive control. (B) Co-IP of MHZ3 with OsEIN2 in planta. Transgenic rice seedlings stably expressing 35S:OsEIN2-GFP or 35S:GFP were treated with 10 ppm ethylene for 3 d. Total proteins were immunoprecipitated with GFP-Trap and immunoblotted with anti-GFP, anti-MHZ3, and anti-BiP (internal control) antibodies. (C) Diagrams of full-length and truncated versions of MHZ3 (Upper) and OsEIN2 (Lower) used in interaction domain mapping studies. (D) Co-IP assays for interaction domain mapping of MHZ3 and OsEIN2. The SP-TM-cYFP-Myc construct contains SP and TM of MHZ3 and was used as a negative control. The constructs were cotransformed into rice protoplasts. Total proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc affinity gel and immunoblotted with anti-c-Myc, anti-FLAG, and anti-BiP antibodies.

Next, we performed interaction domain mapping by using Co-IP assay in rice protoplasts of Osein2 mhz3 double-knockout mutant. MHZ3 was divided into N- terminal (MHZ3-N) and C-terminal (MHZ3-C) halves, both of which contained the SP and TM to ensure proper membrane topology of the truncated proteins (Fig. 4C). OsEIN2 was divided into Nramp-like domain (OsEIN2-N) and C-terminal domain (OsEIN2-C) (Fig. 4C). MHZ3-N and MHZ3-C strongly coprecipitated with OsEIN2 (Fig. 4D, Left). Unexpectedly, both MHZ3-N and MHZ3-C associated with OsEIN2-N, but not with OsEIN2-C (Fig. 4D, Center and Right). Interaction domain mapping was confirmed by BiFC assays in rice protoplasts (SI Appendix, Fig. S11B). The results suggest that MHZ3 interacts with OsEIN2 by associating with its Nramp-like domain. Interestingly, MHZ3-N can also interact with the mutated Osein2-1-N (Fig. 4D, Center and SI Appendix, Fig. S11B). This provides a potential molecular basis for recovery of the ethylene response of Osein2-1 by MHZ3 overexpression.

MHZ3 Is Required for Proper Accumulation of OsEIN2.

Given that MHZ3 physically interacts with OsEIN2, we examined the effects of MHZ3 on OsEIN2 activity. GFP tagging does not affect OsEIN2 function (SI Appendix, Fig. S12A). A similar ER localization pattern of OsEIN2 was observed in the WT and mhz3 protoplasts transiently expressing OsEIN2-GFP, suggesting that MHZ3 does not influence the subcellular localization of OsEIN2, although the percentage of fluorescent cells in the mhz3 background is obviously lower as compared with WT (SI Appendix, Fig. S12B). Moreover, nucleus-localized OsEIN2 C-terminal fragments were detected in both WT and mhz3 plants stably expressing the OsEIN2-GFP transgene, indicating that MHZ3 does not affect the nuclear translocation of OsEIN2 C-terminal domain (SI Appendix, Fig. S12C). Gene expression analysis revealed that neither mhz3 mutation nor MHZ3 overexpression significantly altered the transcript levels of OsEIN2 compared with those in WT seedlings (SI Appendix, Fig. S13), suggesting that MHZ3 does not affect OsEIN2 expression at the transcriptional level.

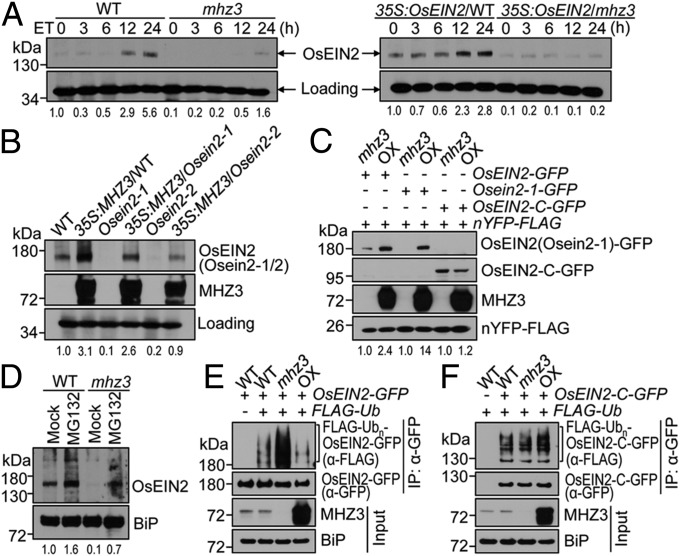

Next, we examined the effects of MHZ3 on OsEIN2 protein level. We generated a specific anti-OsEIN2 antibody to detect the endogenous OsEIN2 protein. In WT seedlings, the level of OsEIN2 protein was apparently elevated by ethylene treatment (Fig. 5A, Left). However, in mhz3 seedlings, OsEIN2 was nearly undetectable at most time points, and only a slight accumulation of the protein was observed after 24 h of ethylene treatment (Fig. 5A, Left). Similarly, in the OsEIN2-overexpressing line in the WT background, the OsEIN2 level gradually increased upon ethylene treatment, but in the mhz3 background, OsEIN2 was detected at very low levels, and no detectable accumulation of the protein was observed upon ethylene treatment (Fig. 5A, Right). The results suggest that mhz3 mutation reduces the basal OsEIN2 level and attenuates ethylene-induced OsEIN2 accumulation. Furthermore, we tested the effect of MHZ3 overexpression on OsEIN2 protein level in WT, Osein2-1, and Osein2-2 backgrounds using the transgenic lines in Fig. 3 C and D. MHZ3 overexpression markedly elevated OsEIN2 abundance in WT seedlings (Fig. 5B). Similarly, overexpression of MHZ3 in Osein2-1 and Osein2-2 backgrounds apparently enhanced accumulation of the Osein2 mutant proteins which were almost undetectable in the single mutants (Fig. 5B). The results suggest that MHZ3 overexpression facilitates the accumulation of both WT and mutated OsEIN2 proteins. Together, our data demonstrate that MHZ3 is indispensable for the proper accumulation of OsEIN2 protein.

Fig. 5.

MHZ3 is required for OsEIN2 accumulation and impedes the protein ubiquitination. (A) Ethylene-induced OsEIN2 accumulation is impaired by mhz3 mutation. Etiolated 2-d-old seedlings of WT, mhz3, and 35S:OsEIN2 transgenic lines (the same lines as in Fig. 3B) were treated with 10 ppm ethylene for 0 to 24 h. Total proteins were immunoblotted for OsEIN2. A nonspecific band was used as a loading control. The values at the bottom indicate averages of relative OsEIN2 levels from three independent replicates; this is same in B–D. (B) MHZ3 overexpression elevates OsEIN2 abundance. Total proteins isolated from etiolated 2-d-old seedlings of WT, Osein2 mutants, and 35S:MHZ3 transgenic lines (the same lines as in Fig. 3 C and D) were immunoblotted for OsEIN2 and MHZ3. Others are as in A. (C) The Nramp-like domain of OsEIN2 is crucial for MHZ3-mediated OsEIN2 accumulation. The constructs were cotransformed into mhz3 and MHZ3-OX22 (OX) protoplasts. nYFP-FLAG served as an internal control for normalizing the transformation efficiency. Total proteins were immunoblotted with anti-GFP, anti-FLAG, and anti-MHZ3 antibodies. (D) OsEIN2 protein in mhz3 mutant is stabilized by MG132. (E and F) Ubiquitination analysis for OsEIN2 (E) and OsEIN2-C (F) in different MHZ3 backgrounds. The constructs were cotransformed into rice protoplasts and incubated in the presence of 3 µM MG132 for 16 h. Total proteins were immunoprecipitated using GFP-Trap and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG and anti-GFP antibodies. Input proteins were immunoblotted for MHZ3 and BiP (loading control).

The Association of MHZ3 with OsEIN2 Nramp-Like Domain Is Crucial for OsEIN2 Accumulation.

To evaluate the specificity of the MHZ3-OsEIN2 interaction for OsEIN2 accumulation, we examined the effect of MHZ3 on the accumulation of the OsEIN2 C-terminal domain, which could not interact with MHZ3 as shown earlier (Fig. 4D). GFP-tagged full-length OsEIN2 and Osein2-1 and the truncated OsEIN2 C-terminal domain were transiently expressed in rice protoplasts isolated from mhz3 mutant and MHZ3-OX (OX22) seedlings. The full-length OsEIN2 and Osein2-1 proteins obviously accumulated when expressed in OX22 protoplasts compared with those in the mhz3 mutant (Fig. 5C). This is consistent with the observations in stable transgenic plants (Fig. 5B). By contrast, no significant difference in the protein levels of the truncated OsEIN2 C-terminal domain was detected when expressed in mhz3 mutant and OX22 backgrounds (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that the N-terminal Nramp-like domain is required for the MHZ3-mediated accumulation of OsEIN2 protein. Consequently, it can be concluded that the binding of MHZ3 to the OsEIN2 Nramp-like domain is crucial for OsEIN2 accumulation.

MHZ3 Impedes OsEIN2 Ubiquitination.

To explore the underlying mechanisms by which MHZ3 stabilizes OsEIN2, we treated mhz3 seedlings with the proteasome inhibitor MG132. The treatment partially restored OsEIN2 accumulation in mhz3 mutant, suggesting that MHZ3 modulates OsEIN2 accumulation through the proteasomal pathway (Fig. 5D). Next, we examined the ubiquitination of OsEIN2 in different MHZ3 backgrounds using the protoplast transient expression system. Compared with that in WT protoplasts, the ubiquitination level of OsEIN2 was obviously enhanced in mhz3 mutant but suppressed in MHZ3-OX backgrounds, suggesting that MHZ3 negatively modulates OsEIN2 ubiquitination (Fig. 5E). In comparison with the full-length OsEIN2, no significant difference in the ubiquitination level of the OsEIN2 C-terminal domain was detected in WT, mhz3, and MHZ3-OX backgrounds (Fig. 5F), implying that the N-terminal Nramp-like domain of OsEIN2 is required for MHZ3-modulated OsEIN2 ubiquitination. Collectively, our results suggest that MHZ3 stabilizes OsEIN2 likely by binding to its Nramp-like domain and impeding protein ubiquitination.

In addition to OsEIN2, we also investigated the effects of MHZ3 on the protein levels of other ER-localized ethylene signaling components, including OsETR2, OsERS2, and OsCTR2 (32). Transient expression of Myc- or GFP-tagged OsETR2, OsERS2, or OsCTR2 in rice protoplasts from WT, mhz3, and MHZ3-OX seedlings revealed that the protein levels of the ethylene receptors and OsCTR2 were unaffected by MHZ3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S14).

Discussion

In this study, we identified a modulator of OsEIN2 function. Interaction with MHZ3 is required for the proper accumulation of OsEIN2 protein. MHZ3 stabilizes OsEIN2 likely by binding to its Nramp-like domain and impeding protein ubiquitination, avoiding proteasome-mediated protein degradation. Since the MHZ3 sequence is conserved from algae to land plants, the mhl1 mhl2 double mutant of Arabidopsis homologous genes exhibits similar ethylene-insensitive phenotypes; and since the known ethylene signaling components are functionally conserved between lower and higher plants (33), the potential regulatory mechanism of MHZ3 in ethylene signaling may be conserved throughout the plant kingdom.

Multiple lines of genetic evidence suggest that MHZ3 acts at the OsEIN2 level in the ethylene signaling pathway. MHZ3 directly interacts with OsEIN2 as demonstrated from the Y2H, Co-IP, and BiFC assays in our study. Protein–protein interaction usually plays a crucial role in regulation of protein stabilization (34–36). Presently, interaction with MHZ3 is required for OsEIN2 accumulation, but not for the ER localization or nuclear translocation of OsEIN2. Our biochemical data show that MHZ3 interacts with OsEIN2 through binding to its N-terminal Nramp-like domain. Without the Nramp-like domain, MHZ3 was unable to stabilize OsEIN2, demonstrating that association of MHZ3 with the OsEIN2 Nramp-like domain is crucial for OsEIN2 accumulation. Importantly, MHZ3-inhibited OsEIN2 ubiquitination also depends on the presence of the Nramp-like domain. Although extensive studies have demonstrated that the C-terminal domain of EIN2 can be cleaved and translocated into the nucleus and P-body to activate downstream signaling (7, 13, 15, 16, 19, 20), the function of its N-terminal Nramp-like domain has long been unknown. Expression of the EIN2 C-terminal domain in ein2-5 was unable to restore the triple response, suggesting that the Nramp-like domain is essential for triggering ethylene responses in Arabidopsis etiolated seedlings (7). Our findings provide a potential mechanism for how EIN2 works through its Nramp-like transmembrane domain.

Ubiquitination analyses revealed that MHZ3 impedes OsEIN2 ubiquitination likely by binding to its N-terminal Nramp-like domain; however, the underlying mechanism is not clear. One possibility is that the binding of MHZ3 to the OsEIN2 Nramp-like domain may lead to a conformational change in the protein, preventing the binding of ETP1/ETP2-like proteins to OsEIN2 for degradation. Unfortunately, ETP1/ETP2-like genes were not identified in the rice genome (37). Thus, identification of the F-box proteins involved in OsEIN2 degradation is necessary to elucidate the mechanisms by which MHZ3 stabilizes OsEIN2. On the other hand, ethylene receptors, CTR1, and EIN2 can form a signaling complex on the ER through protein–protein interactions (38–40). Therefore, as an alternative mode of action, MHZ3 may function as a molecular chaperone involved in the regulation of the signaling complex, although the protein levels of OsETR2, OsERS2, and OsCTR2 were not affected by MHZ3.

It should be noted that although ethylene induces MHZ3 expression, the fact that the 35S:MHZ3-GFP transgene can restore normal ethylene response in mhz3 mutant suggests that the ethylene regulation of MHZ3 may be dispensable for the function of this gene in the ethylene response. Additionally, MHZ3 overexpression with massive accumulation of the protein leads to only slight ethylene hypersensitivity. In contrast, mild accumulation of MHZ3 in response to ethylene is sufficient to trigger ethylene response. These facts suggest an alternative mechanism by which MHZ3 may play a housekeeping role rather than a regulatory function in the signaling pathway.

Collectively, we identified the ethylene-induced and ER-localized modulator MHZ3, which interacts with the Nramp-like domain of OsEIN2 and stabilizes the protein to facilitate ethylene signaling. Manipulation of the gene may improve agronomic traits, especially in food crops.

Materials and Methods

Details for plant growth and ethylene-response assay, gene expression analysis, protein fractionation, membrane-based Y2H assay, Co-IP and BiFC assays, and ubiquitination analysis are described in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods. The primers used in this study are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Wei-Cai Yang for kindly providing the pCAMBIA1300-35S-mCherry-HDEL plasmid and Drs. Hao-Wei Chen, Jian-Jun Tao, and Cui-Cui Yin for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 31670274 and 31530004), the 973 Project (Grant 2015CB755702), and the State Key Laboratory of Plant Genomics.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. C.C. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1718377115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ju C, Chang C. Mechanistic insights in ethylene perception and signal transduction. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:85–95. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang C, Kwok SF, Bleecker AB, Meyerowitz EM. Arabidopsis ethylene-response gene ETR1: Similarity of product to two-component regulators. Science. 1993;262:539–544. doi: 10.1126/science.8211181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hua J, Chang C, Sun Q, Meyerowitz EM. Ethylene insensitivity conferred by Arabidopsis ERS gene. Science. 1995;269:1712–1714. doi: 10.1126/science.7569898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen YF, Randlett MD, Findell JL, Schaller GE. Localization of the ethylene receptor ETR1 to the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19861–19866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma B, et al. Subcellular localization and membrane topology of the melon ethylene receptor CmERS1. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:587–597. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.080523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieber JJ, Rothenberg M, Roman G, Feldmann KA, Ecker JR. CTR1, a negative regulator of the ethylene response pathway in Arabidopsis, encodes a member of the raf family of protein kinases. Cell. 1993;72:427–441. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90119-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alonso JM, Hirayama T, Roman G, Nourizadeh S, Ecker JR. EIN2, a bifunctional transducer of ethylene and stress responses in Arabidopsis. Science. 1999;284:2148–2152. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chao Q, et al. Activation of the ethylene gas response pathway in Arabidopsis by the nuclear protein ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and related proteins. Cell. 1997;89:1133–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solano R, Stepanova A, Chao Q, Ecker JR. Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: A transcriptional cascade mediated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3703–3714. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang KN, et al. Temporal transcriptional response to ethylene gas drives growth hormone cross-regulation in Arabidopsis. eLife. 2013;2:e00675. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bisson MM, Bleckmann A, Allekotte S, Groth G. EIN2, the central regulator of ethylene signalling, is localized at the ER membrane where it interacts with the ethylene receptor ETR1. Biochem J. 2009;424:1–6. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hua J, Meyerowitz EM. Ethylene responses are negatively regulated by a receptor gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell. 1998;94:261–271. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ju C, et al. CTR1 phosphorylates the central regulator EIN2 to control ethylene hormone signaling from the ER membrane to the nucleus in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:19486–19491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214848109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiao H, Chang KN, Yazaki J, Ecker JR. Interplay between ethylene, ETP1/ETP2 F-box proteins, and degradation of EIN2 triggers ethylene responses in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2009;23:512–521. doi: 10.1101/gad.1765709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiao H, et al. Processing and subcellular trafficking of ER-tethered EIN2 control response to ethylene gas. Science. 2012;338:390–393. doi: 10.1126/science.1225974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wen X, et al. Activation of ethylene signaling is mediated by nuclear translocation of the cleaved EIN2 carboxyl terminus. Cell Res. 2012;22:1613–1616. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang F, et al. EIN2-dependent regulation of acetylation of histone H3K14 and non-canonical histone H3K23 in ethylene signalling. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13018. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang F, et al. EIN2 mediates direct regulation of histone acetylation in the ethylene response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:10274–10279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707937114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W, et al. EIN2-directed translational regulation of ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2015;163:670–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merchante C, et al. Gene-specific translation regulation mediated by the hormone-signaling molecule EIN2. Cell. 2015;163:684–697. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo H, Ecker JR. Plant responses to ethylene gas are mediated by SCF(EBF1/EBF2)-dependent proteolysis of EIN3 transcription factor. Cell. 2003;115:667–677. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00969-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Potuschak T, et al. EIN3-dependent regulation of plant ethylene hormone signaling by two Arabidopsis F box proteins: EBF1 and EBF2. Cell. 2003;115:679–689. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00968-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma B, Chen SY, Zhang JS. Ethylene signaling in rice. Chin Sci Bull. 2010;55:2204–2210. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goff SA, et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica) Science. 2002;296:92–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma B, et al. Identification of rice ethylene-response mutants and characterization of MHZ7/OsEIN2 in distinct ethylene response and yield trait regulation. Mol Plant. 2013;6:1830–1848. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang C, et al. MAOHUZI6/ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3-LIKE1 and ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3-LIKE2 regulate ethylene response of roots and coleoptiles and negatively affect salt tolerance in rice. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:148–165. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma B, et al. Ethylene-induced inhibition of root growth requires abscisic acid function in rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin CC, et al. Ethylene responses in rice roots and coleoptiles are differentially regulated by a carotenoid isomerase-mediated abscisic acid pathway. Plant Cell. 2015;27:1061–1081. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiong Q, et al. Ethylene-inhibited jasmonic acid biosynthesis promotes mesocotyl/coleoptile elongation of etiolated rice seedlings. Plant Cell. 2017;29:1053–1072. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang C, Lu X, Ma B, Chen SY, Zhang JS. Ethylene signaling in rice and Arabidopsis: Conserved and diverged aspects. Mol Plant. 2015;8:495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.An F, et al. Ethylene-induced stabilization of ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3 and EIN3-LIKE1 is mediated by proteasomal degradation of EIN3 binding F-box 1 and 2 that requires EIN2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2384–2401. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.076588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Q, Zhang W, Yin Z, Wen CK. Rice CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE-RESPONSE2 is involved in the ethylene-receptor signalling and regulation of various aspects of rice growth and development. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:4863–4875. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ju C, et al. Conservation of ethylene as a plant hormone over 450 million years of evolution. Nat Plants. 2015;1:14004. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2014.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon GM, Kieber JJ. 14-3-3 Regulates 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase protein turnover in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:1016–1028. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.110106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Botër M, et al. Structural and functional analysis of SGT1 reveals that its interaction with HSP90 is required for the accumulation of Rx, an R protein involved in plant immunity. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3791–3804. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang X, et al. Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G proteins regulate immunity by directly coupling to the FLS2 receptor. eLife. 2016;5:e13568. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Navarro-Quezada A, Schumann N, Quint M. Plant F-box protein evolution is determined by lineage-specific timing of major gene family expansion waves. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao Z, et al. Localization of the Raf-like kinase CTR1 to the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis through participation in ethylene receptor signaling complexes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34725–34732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bisson MM, Groth G. New insight in ethylene signaling: Autokinase activity of ETR1 modulates the interaction of receptors and EIN2. Mol Plant. 2010;3:882–889. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bisson MM, Groth G. New paradigm in ethylene signaling: EIN2, the central regulator of the signaling pathway, interacts directly with the upstream receptors. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6:164–166. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.1.14034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.