Abstract

Bacterial microcompartments are giant protein-based organelles that encapsulate special metabolic pathways in diverse bacteria. Structural and genetic studies indicate that metabolic substrates enter these microcompartments by passing through the central pores in hexameric assemblies of shell proteins. Limiting the escape of toxic metabolic intermediates created inside the microcompartments would confer a selective advantage for the host organism. Here, we report the first molecular dynamics (MD) simulation studies to analyze small-molecule transport across a microcompartment shell. PduA is a major shell protein in a bacterial microcompartment that metabolizes 1,2-propanediol via a toxic aldehyde intermediate, propionaldehyde. Using both metadynamics and replica-exchange umbrella sampling, we find that the pore of the PduA hexamer has a lower energy barrier for passage of the propanediol substrate compared to the toxic propionaldehyde generated within the microcompartment. The energetic effect is consistent with a lower capacity of a serine side chain, which protrudes into the pore at a point of constriction, to form hydrogen bonds with propionaldehyde relative to the more freely permeable propanediol. The results highlight the importance of molecular diffusion and transport in a new biological context.

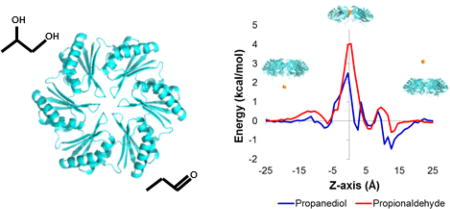

Table of Contents artwork

1. Introduction

Diverse biological processes rely on the regulated transport of small molecules across barriers between cells or between different subcellular compartments. Membrane proteins and channels enable the regulated movement of molecules across lipid bilayers; molecular transport in transmembrane protein systems has been studied at the functional and structural level for over 50 years.1, 2 Recently, an entirely distinct class of proteins has come under investigation in the context of molecular transport into and out of giant protein-based organelles known as bacterial microcompartments. These structures act in diverse bacterial species to sequester key enzymatic pathways that involve toxic or volatile chemical intermediates,3–5 while metabolic substrates must enter and products must escape through diffusive processes.

The outer shells of bacterial microcompartments are formed primarily by a tightly packed layer of hexameric proteins known as BMC shell proteins. These proteins assemble into cyclic hexamers with a narrow central pore. The pore has been shown experimentally to be the route for diffusive molecular transport in these systems (Figure 1).6, 7 The starting substrate for the encapsulated pathway must pass efficiently from the cytosol into the microcompartment interior. Furthermore, it has been argued that a physiological advantage would be conferred by a pore that is less permeable to volatile or cytotoxic intermediates produced in the interior, which would otherwise escape the microcompartment and damage the cell's DNA.8 Moreover, amino acid mutations in the pore that allow more rapid aldehyde release do cause growth defects.7 However, to date it has not been possible to measure experimentally the relative permeabilities of the starting substrate and the toxic intermediate. This is due to the complexity of bacterial microcompartments, which are comprised of thousands of shell proteins and enzyme molecules, and the difficulties of direct transport studies in vitro. Crystal structures of the relevant BMC shell proteins6, 7 offer opportunities to examine their transport properties in atomistic detail via molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

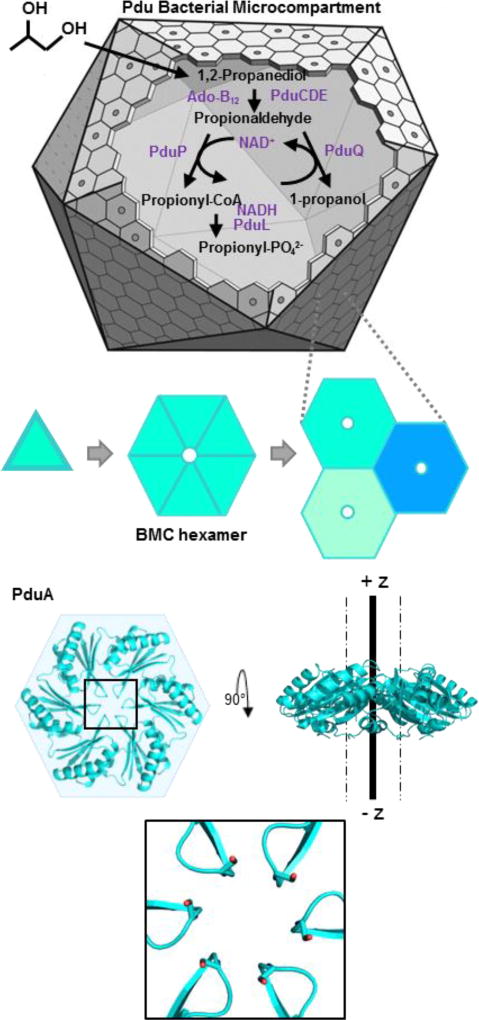

Figure 1.

Assembly and molecular transport across the bacterial PduA shell proteins in the Pdu microcompartment. The 1,2-propanediol utilization (Pdu) pathway catabolizes 1,2-propanediol via a toxic aldehyde intermediate. PduA is a BMC shell protein of the Pdu microcompartment and is the route of substrate (1,2-propanediol) entry. The thick line, running from −z to +z, indicates the molecular six-fold axis; the pair of broken lines parallel to this axis demarcate the radial limits (in our cylindrical coordinate system). Inset shows a zoomed in view of the PduA hexamer pore (cartoon) showing residue S40 lining the pore (radius 2.8Å).

In this first study of molecular transport through BMC shell proteins, we examine the hexameric shell protein known as PduA, whose structure we determined in an earlier study.6 The PduA pore is the route for the diffusive influx of 1,2-propanediol into the Pdu microcompartment. The encapsulated enzymes transform the substrate into the cytotoxic intermediate propionaldehyde and then into non-toxic metabolites. These last steps must occur before the aldehyde can diffuse outward across the shell and into the cytosol.7–9 We tested the hypothesis that the PduA pore is more permeable to the propanediol (PDO) substrate compared to the propionaldehyde (PPN) intermediate by computing free energy profiles of the two small molecules along the diffusion pathway across the pore.

2. Methods

The atomic coordinates for PduA are from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 (PDB code: 3NGK). An infinite 2-D layer of PduA hexamer proteins was effectively constructed via periodic boundary conditions, using a hexagonal prism solvation box with 30 Å between the centers of mass of two PduA layers. The system was protonated at pH 7.0 and solvated with approximately 40,000 TIP3P waters. Na+ or Cl− ions were added to neutralize the charge on the PduA hexamers using the Xleap program in AmberTools14.10, 11 The Amber FF99SB force field12 was used to describe the energetics of the protein. For the parameterizations of the small molecules, we followed the recommended procedure for General Amber Force Field (GAFF), as described earlier.13 The geometries of the small molecules were optimized at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory using Gaussian 09 software.14 The lowest energy conformer of each metabolite was identified and used to assign force field parameters (see Supporting Data for details). The covalent energy parameters as well as Lennard-Jones radii of the constituent atoms were parametrized using AmberTools14. Atomic partial charges were assigned via the Restrained Electrostatic Potential (RESP) method.15 We used Antechamber software included in AmberTools14 to deduce atomic partial charges that best fit the spatial charge distribution from the single point energies computed at the HF/6-31G(d)//B3LYP/6-31G(d) level theory. The optimized geometries of the metabolites in gas phase as well as the RESP charges used throughout the MD simulations are given in Table S1.

Each solvated system was (i) energy-minimized over 500 steps with restraints imposed to Cα atoms (ii) heated from 0 to 300 K over 1 ns of dynamics, (iii) equilibrated in the NVT ensemble, and then (iv) propagated as an equilibration run in the NPT ensemble for 10 ns. The pressure of the solvated system was controlled by scaling the three periodic unit cell dimensions independently in NPT equilibration and production. The temperature was regulated by employing Langevin thermostat with a collision frequency of 5.0 ps−1 using an integration time step of 2 fs. Long-range electrostatic interactions were modeled using the particle mesh Ewald method16 and Lennard-Jones interactions were cutoff at 9Å. The The systems were then treated according to the MD techniques applied using NAMD 2.9 molecular simulation software.17

For the metadynamics simulations, replicas of each system were simulated in parallel, following the general approach of Raiteri et al.18 The number of replicas was chosen to maximize computation speed and efficiency. The well-tempered metadynamics algorithm19, 20 was used in order to achieve relatively smoothly converging free energy profiles. The bias temperature was 500 K, the default hill height was 0.01 kcal/mol, the default hill width was , and the hill update frequency was 1000 MD steps. The collective variables module implemented in NAMD software was used to define the cylindrical coordinate system specific to the metabolites of interest.21 Of note, the coordinate origin of the collective variables were simultaneously evolving with the center of the Pdu pore constriction. The small molecules were restrained from moving > 15 Å from the z-axis.

For REUS22 simulations, the small molecules were restrained with a 0.5 kcal/mol/Å2 spring constant, at 59 overlapping windows of width 0.5 Å across the z-axis through the PduA pore. Additionally, to keep the metabolite within the cylindrical guide, a restraining force (100 kcal/mol/Å) was applied to its center of mass when its radial coordinate exceeded 15 Å from the z-axis. For every 500 MD steps, replica exchange trials were made following the Metropolis criterion.23 The acceptance ratios for the simulations of 1,2-propanediol and propionaldehyde were 0.20 and 0.21, respectively.

For conventional MDs (cMD), production simulations were extended for 100ns (for 3 replicas) with the small molecules restrained with a spring constant of 2.0 kcal/mol/Å2 at z=0.5Å, and 0 ≤ r ≤ 5 Å in the PduA pore. The cMD trajectories were analyzed using the hydrogen bond analysis tool in VMD software.24

3. Results and Discussions

We carried out a series of metadynamics MD simulations to quantify the energy barrier that a metabolite experiences across the PduA pore. In the PduA hexamer system, the center of mass of a small molecule was chosen as the collective variable describing the reaction coordinate for diffusion within the hexamer pore region (Fig. 1). We defined a cylindrical coordinate system relative to the pore center, where the z-axis passes through the center of the pore and positive values of z correspond to the side believed to face the cytosol. The radial distance from the z-axis (r) and the vertical position (z) of the small molecule were analyzed in all simulations. In order to model an intact two-dimension layer of protein molecules, the hexameric PduA shell protein was constructed as a tiled layer, as would be found on a flat facet of the Pdu microcompartment shell.6, 25 In addition to the PduA hexamer, our simulation systems contain explicit solvent and a small molecule, either the substrate 1,2-propanediol (PDO) or the intermediate propionaldehyde (PPN) (see Supporting Data for details). In the metadynamics approach, the Hamiltonian of the solvated system is augmented with a history-dependent bias potential (Vmeta). The bias potential gradually flattens the underlying energy landscape for a given set of reaction coordinates (i.e., collective variables). The flattening process ultimately reduces energy barriers between energy minima and accelerates sampling of the system’s phase space. Without a biasing potential, conventional unbiased MD simulations are often too slow in exploring important but rare events in complex systems with rugged energy landscapes. Upon convergence of a metadynamics simulation, the biasing potential reveals the underlying (unbiased) free energy landscape defined by the collective variables.19, 21, 26. (See Supporting Data for handling of the Jacobian term for the cylindrical coordinate system employed).

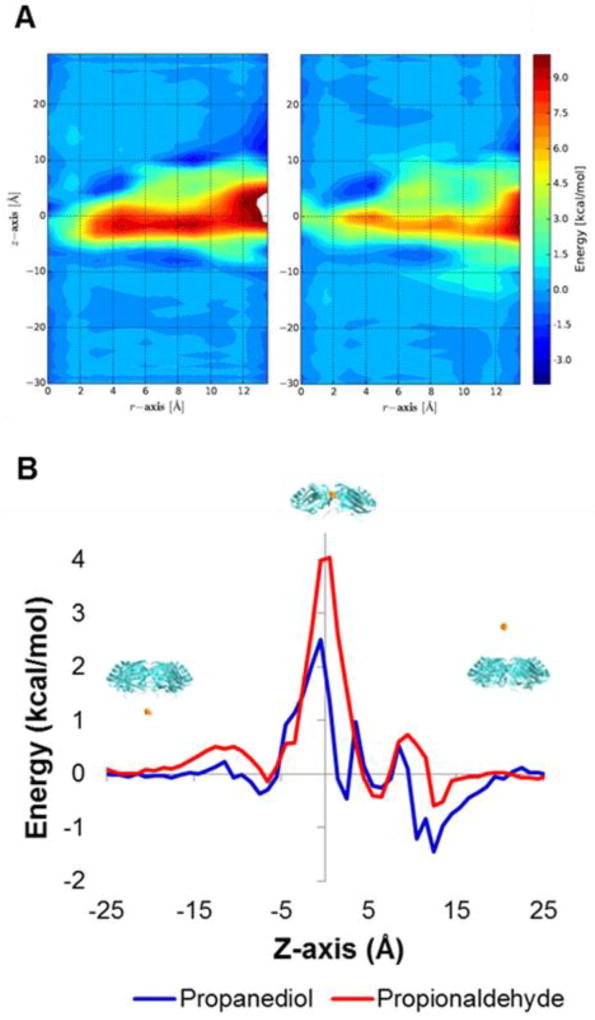

Figure 2 shows the potential of mean force (PMF) profile of the two metabolites through the PduA pore. The dynamics of diffusing small molecules (PDO and PPN) were simulated across the PduA pore, with the accumulated simulation time of 648 ns. Each molecule was confined within a cylinder whose radius was 15 Å and height was 60 Å. The center of geometry of the cylinder was aligned with the PduA pore. Inside the PduA protein (−8 Å < z < 8 Å), each substrate experiences a higher energy than in the bulk solvent region (z > 8 Å or z < −8 Å) (Fig. 2 A). Minima of the potential energy barriers are found near the center of the pore (z=0 Å and r=0 Å). The computed barrier height for PDO is 2.4±0.1 kcal/mol and for PPN is 3.9±0.2 kcal/mol. As expected, the path of lowest energy passes through the open center of the pore rather than through interior regions of the protein molecules. A comparison of the two potential of mean force profiles through the pore reveals that the aldehyde (PPN) experiences a higher free-energy barrier, by 1.5 kcal/mol, in the middle of the pore near z=0 Å (Fig. 2B). We averaged the PMF over the radial coordinate (r) to achieve the 1 dimensional PMF profile along the axial coordinate (z).

Figure 2.

Metadynamics potential of mean force profiles for small molecules diffusing through the PduA hexamer pore represented as (A) 2-dimensional heatmaps for propanediol (left) and propionaldehyde (right), and as (B) 1-dimensional line plots through the center of the pore for propanediol (blue) and propionaldehyde (red).

We compared relative permeabilities of the diffusing metabolites using microscopic theories of molecular diffusion.27 In a simplified treatment, the rate of transport is dictated only by the free energy peak height according to the Boltzmann distribution, and the peak height energy difference between the two cases provides an indication of the relative permeability:

| (1) |

where Prel is the relative permeability, β = 1/kBT is the Boltzmann factor at room temperature, and and are the energy barrier heights of PDO and PPN, respectively. With an energy difference in the present case of 1.5 kcal/mol, the relative permeability ratio would be about 13 in favor of the PDO substrate. A more sophisticated treatment of diffusive rates can account for the full free energy profiles as a function of the axial position, z. An expression of the following form can be obtained for the diffusive permeability:

| (2) |

where P is the permeability, D is the diffusion coefficient, and G(z) is the free energy as a function of the radial coordinate, z. When averaged over the last 180 ns of the metadynamics MD simulations, the computed relative permeability is 9.7±1.8. This improved estimate differs only modestly from the value obtained by the simpler treatment of peak heights. The derivation of Eq. 2 is explained in the Supporting Data. Our derivation of permeability of small molecules diffusing through a channel parallels the study by Bauer and Nadler on the transport of particles that can bind in a channel.28 Of note, the experimental diffusion coefficients of the two metabolites in water are similar: D = 1.0 × 10−5cm2/s for PDO and 1.15 × 10−5cm2/s for PPN29. We also analyzed the diffusion coefficients of the two metabolites during MD simulations computationally (see Supporting Data IV). We found good agreement for the computed diffusion coefficients for the metabolites in water, and a similar reduction by a factor of approximately two for both metabolites when present near the center of the PduA pore. Thus, in comparing the relative permeabilities, we ignored small differences in the diffusion coefficients for the two molecules in question (i.e. we accounted only for the denominator term in equation (2)), and evaluated the integral over the range of z values corresponding to the region of constriction in the pore (−5.5 Å < z < 5.5 Å). In short, we conclude that the 1,2-propanediol metabolite has a permeability roughly 10 times higher than that of propionaldehyde.

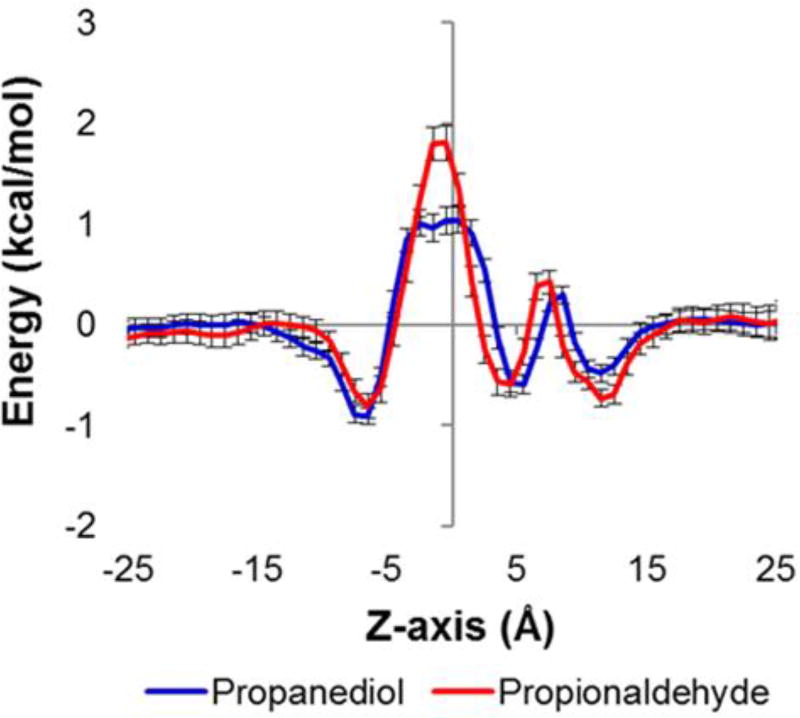

To validate our results by another independent method, we employed replica exchange umbrella sampling (REUS)11–14 to examine the PMF of the two small molecules through the PduA pore. The PMF profiles in the bulk solvent region (|z| > 8 Å) computed by the metadynamics MD simulations fluctuate significantly, a drawback of metadynamics MD simulations reported previously.30 In REUS, the small molecule was restrained, with a 0.5 kcal/mol/Å2 spring constant, at 59 overlapping windows of width 1.0 Å across the z-axis through the PduA pore. The REUS simulations were computed for 1003 ns and 590 ns for PDO and PPN, respectively. The total simulation time analyzed for PDO was twice as long as that for PPN, since the simulations of PDO converged more slowly. Once finished, PMF profiles were evaluated using the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM).31, 32 Figure 3 shows the PMF profiles of PDO and PPN through the WT PduA pore. The computed barrier height of PDO from the US simulations is 1.0±0.2 kcal/mol and that for PPN is 1.7±0.3 kcal/mol. The results indicate a barrier for PPN that is about 0.7 kcal/mol higher than that of PDO. (see Supporting Data for details of the error analysis). Following the same treatment as described above for analyzing the effects of the free energy profile, the permeability of the propanediol substrate is calculated to be 3.2±1.8 times higher than that of the propionaldehyde intermediate, using the simplified treatment for the relative permeability (Eq. 1).

Figure 3.

PMF profiles of propanediol (blue) and propionaldehyde (red) through the PduA hexamer pore, computed from REUS simulations. Consistent with the metadynamics-based PMF (Figure 2), note that the propionaldehyde energy barrier (red trace) exceeds the propanediol peak near z = 0.

While the energy profiles based on the two molecular dynamics methods are well-correlated (Fig. 2B, Fig. 3), the differences in the peak magnitudes obtained in the two cases are notable. For instance, the barrier height of PDO at the center is 2.5 kcal/mol from the metadynamics MD simulations and 1.0 kcal/mol from the REUS simulations, and a similar deviation is seen for the case of PPN. We ascribe this to systematic differences in the application of collective variables in the two approaches: e.g. a 2-dimensional radial and axial system in the metadynamics MD vs a series of effectively 1-dimensional radial simulations (one at each z value) in the REUS. A relevant issue in our REUS approach is that, by evaluating energies separately at each z value, differences (as a function of z) in the natural entropic costs associated with confining the metabolites to narrower regions of the pore are overlooked. This important aspect of the energetics is accounted for in our metadynamics approach, because it considers the radial and axial dimensions together. Indeed, the energy barriers are found to be higher with this method in the constricted regions of the pore. This illustrates the nuances involved in analyzing the energetics of transport in complex systems using different computational approaches. Importantly, despite such issues, both methods applied here agree on the conclusion that the energetics favor permeability of PPO over PPN, with the more complete metadynamics treatment indicating the higher difference in permeability between the two metabolites.

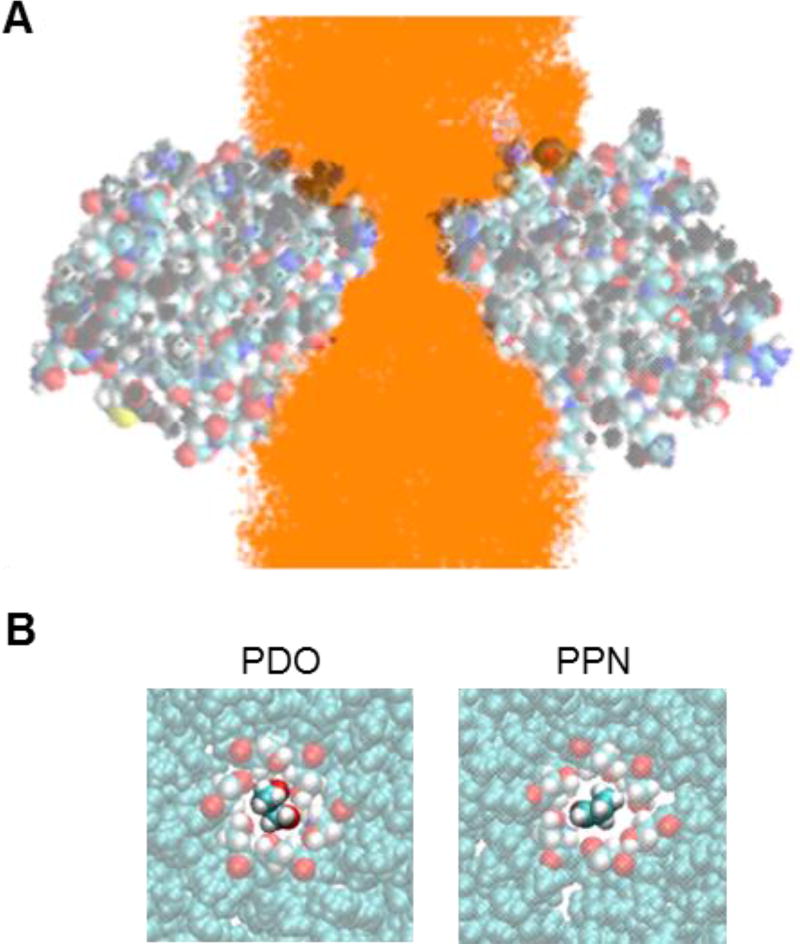

We analyzed the positions occupied by the metabolites during the course of the metadynamics MD simulations to ensure that transport was through the pore (Fig. 4A). As anticipated, the passage of small molecules across the PduA hexamer is only through the pore and not through residues or holes in the regions surrounding the pore. This path coverage was observed for both PDO and PPN through the PduA hexamer pore in the metadynamics MD simulations as well as the replica exchange umbrella sampling (REUS).

Figure 4.

(A) Path coverage of a small molecule (orange points) through the PduA hexamer pore (translucent spheres, cytosolic face up), shown as a cross-sectional view. (B) Dominant orientation of small molecules PDO (left) and PPN (right) approaching the PduA pore (Ser40 colored by atom type)

To elucidate a possible structural basis for differential permeabilities of the two small molecules, we studied specific interactions that could explain the higher energy barrier encountered by PPN relative to PDO (Fig. 4B). It has been suggested that differences in the hydrogen bonding capacities of the aldehyde vs. the diol might be important, particularly in light of the presence of (six copies of) a serine residue (Ser40) at the point of narrowest constriction in the PduA pore.6 We therefore examined 100 ns of conventional constant temperature-pressure MD trajectories, where each small molecule was restrained at the center of the pore at the position lined by Ser40 residues. We evaluated the number of hydrogen bonds that the Ser40 residues make with either water molecules or diffusing solute (aldehyde or diol) molecules. In the conventional MD runs with the small molecule corralled near the PduA hexamer pore, the six Ser40 residues exhibited an average of 7.8±0.4 hydrogen bonds to waters or small molecule per frame in the presence of PDO, and 6.9±0.6 hydrogen bonds to waters or small molecule per frame with PPN. This result suggests that the serine side chains hydrogen bond more readily with PDO. This is an intuitive finding, given the additional hydrogen bond donor of PDO versus PPN. Hydrogen bonds and other energetic interactions in the pore are expected to enhance the flux of favorably-interacting species. Theoretical analysis has shown that this phenomenon—enhanced translocation by favorable energetic interactions—is explained by a large increase in the probability of a diffusing molecule reaching and occupying the pore; this surmounts the potential increase in mean first passage time that might accompany an energy well.28

4. Conclusion

Our studies of 1,2-propanediol and propionaldehyde with the PduA protein are the first all-atom MD simulations to probe small-molecule transport through the pores of BMC shell proteins. Our MD results provide biophysical evidence to support the hypothesis that the shells of bacterial microcompartments have pores that are evolved to be selective for uptake of the necessary substrates, and less permeable to the metabolic intermediates produced inside. The generality of this result is, however, an open question. In the carboxysome—a different type of microcompartment comprised of shell proteins that are homologous to PduA—structural features (such as a positively charged pore) support the idea that the shell could be more permeable to the negatively charged carboxysome substrate (bicarbonate) versus the CO2 intermediate produced inside.33 However, recent metabolic modeling calculations argue that the carboxysome could operate efficiently without having to be selectively permeable to bicarbonate versus CO2.34

Further study of molecular transport phenomena in diverse microcompartments will be necessary to more fully understand these extraordinary systems. Future MD studies of BMC shell pores could be extended to the alpha and beta-type carboxysomes, ethanolamine utilizing microcompartments, and more recently discovered types that sequester glycyl radical-based enzymatic pathways.33, 35, 36 A clearer view of molecular transport would enlighten the design of more efficient systems, or even novel compartments for the biosynthesis of drugs, therapeutics, and biofuels.37–39

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01AI081146 (TOY and TAB) and NIH grant GM097200 (KNH). SC was supported by the CBI NIH training grant (T32-GM008496) and by the UCLA Graduate Division.

The authors thank Cameron Mura for a critical reading of the manuscript and members of the J. Andrew McCammon laboratory for early discussions. Computations from this work were run and analyzed on the UCLA IDRE Hoffman2 cluster, the Keeneland and Stampede supercomputers through the XSEDE program (TGCHE040013N), and the UCLA-DOE Cassini cluster, supported by the BER program of the DOE Office of Science under award # DEFC02-2ER63421.

Abbreviations

- PDO

1,2-propanediol

- PPN

propionaldehyde

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website in PDF format.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. SC and JP contributed equally to the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Doyle DA, Morais Cabral J, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280(5360):69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacKinnon R. Potassium channels. FEBS Lett. 2003;555(1):62–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chowdhury C, Sinha S, Chun S, Yeates TO, Bobik TA. Diverse bacterial microcompartment organelles. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2014;78(3):438–68. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00009-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeates TO, Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC, Shively JM. Protein-based organelles in bacteria: carboxysomes and related microcompartments. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6(9):681–91. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng S, Liu Y, Crowley CS, Yeates TO, Bobik TA. Bacterial microcompartments: their properties and paradoxes. Bioessays. 2008;30(11–12):1084–95. doi: 10.1002/bies.20830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowley CS, Cascio D, Sawaya MR, Kopstein JS, Bobik TA, Yeates TO. Structural insight into the mechanisms of transport across the Salmonella enterica Pdu microcompartment shell. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(48):37838–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chowdhury C, Chun S, Pang A, Sawaya MR, Sinha S, Yeates TO, Bobik TA. Selective molecular transport through the protein shell of a bacterial microcompartment organelle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(10):2990–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423672112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sampson EM, Bobik TA. Microcompartments for B12-dependent 1,2-propanediol degradation provide protection from DNA and cellular damage by a reactive metabolic intermediate. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(8):2966–71. doi: 10.1128/JB.01925-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Havemann GD, Bobik TA. Protein content of polyhedral organelles involved in coenzyme B12-dependent degradation of 1,2-propanediol in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(17):5086–95. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.17.5086-5095.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Chemical Physics. 1983;79(2):926–35. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Case DA, Babin V, Berryman JT, Betz RM, Cai Q, Cerutti DS, Cheatham TE, III, Darden TA, Duke RE, Gohlke H, Goetz AW, Gusarov S, Homeyer N, Janowski P, Kaus J, Kolossváry I, Kovalenko A, Lee TS, LeGrand S, Luchko T, Luo R, Madej B, Merz KM, Paesani F, Roe DR, Roitberg A, Sagui C, Salomon-Ferrer R, Seabra G, Simmerling CL, Smith W, Swails J, Walker RC, Wang J, Wolf RM, Wu X, Kollman PA. AMBER 14. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hornak V, Abel R, Okur A, Strockbine B, Roitberg A, Simmerling C. Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins. 2006;65(3):712–725. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Wolf RM, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA, Case DA. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25(9):1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JJA, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian~09 Revision D.01. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bayly CI, Cieplak P, Cornell WD, Kollman PA. A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges: the RESP model. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle Mesh Ewald - An N.Log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98(12):10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kalé L, Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26(16):1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raiteri P, Laio A, Gervasio FL, Micheletti C, Parrinello M. Efficient reconstruction of complex free energy landscapes by multiple walkers metadynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110(8):3533–3539. doi: 10.1021/jp054359r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barducci A, Bussi G, Parrinello M. Well-tempered metadynamics: a smoothly converging and tunable free-energy method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100(2):020603–020603. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.020603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonomi M, Parrinello M. Enhanced sampling in the well-tempered ensemble. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;104(19):190601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.190601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiorin G, Klein M, Henin J. Using collective variables to drive molecular dynamics simulations. Mol. Phys. 2013;111(22–23):3345–3362. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugita Y, Kitao A, Okamoto Y. Multidimensional replica-exchange method for free-energy calculations. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2000;113(15):6042–6051. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chemical Physics Letters. 1999;314(1–2):141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dryden KA, Crowley CS, Tanaka S, Yeates TO, Yeager M. Two-dimensional crystals of carboxysome shell proteins recapitulate the hexagonal packing of three-dimensional crystals. Protein Sci. 2009;18(12):2629–35. doi: 10.1002/pro.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bussi G, Laio A, Parrinello M. Equilibrium free energies from nonequilibrium metadynamics. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96(9):090601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.090601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanggi P, Talkner P, Borkovec M. Reaction-rate theory: 50 years after Kramers. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1990;62(2):251–341. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bauer WR, Nadler W. Molecular transport through channels and pores: effects of in-channel interactions and blocking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(31):11446–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601769103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yaws CL. Transport Properties of Chemicals and Hydrocarbons. Elsevier Inc; 2009. pp. 502–596. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cavalli A, Spitaleri A, Saladino G, Gervasio FL. Investigating drug-target association and dissociation mechanisms using metadynamics-based algorithms. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48(2):277–85. doi: 10.1021/ar500356n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grossfield A. WHAM: the weighted histogram analysis method, version 2.0.9. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar S, Rosenberg JM, Bouzida D, Swendsen RH, Kollman PA. The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. J. Comput. Chem. 1992;13(8):1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerfeld CA, Sawaya MR, Tanaka S, Nguyen CV, Phillips M, Beeby M, Yeates TO. Protein structures forming the shell of primitive bacterial organelles. Science. 2005;309(5736):936–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1113397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mangan NM, Flamholz A, Hood RD, Milo R, Savage DF. pH determines the energetic efficiency of the cyanobacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(36):E5354–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525145113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka S, Sawaya MR, Yeates TO. Structure and mechanisms of a protein-based organelle in Escherichia coli. Science. 2010;327(5961):81–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1179513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jorda J, Lopez D, Wheatley NM, Yeates TO. Using comparative genomics to uncover new kinds of protein-based metabolic organelles in bacteria. Protein Sci. 2013;22(2):179–95. doi: 10.1002/pro.2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frank S, Lawrence AD, Prentice MB, Warren MJ. Bacterial microcompartments moving into a synthetic biological world. J Biotechnol. 2013;163(2):273–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim EY, Tullman-Ercek D. Engineering nanoscale protein compartments for synthetic organelles. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24(4):627–32. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai F, Sutter M, Bernstein SL, Kinney JN, Kerfeld CA. Engineering bacterial microcompartment shells: chimeric shell proteins and chimeric carboxysome shells. ACS Synth Biol. 2015;4(4):444–53. doi: 10.1021/sb500226j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.