Abstract

Background

Despite supporting scientific evidence, community water fluoridation (CWF) often fails in public referendums. To understand why, the authors quantitatively analyzed text from news media coverage of CWF referendums.

Methods

Text was analyzed from 234 articles covering 11 CWF referendums conducted in three U.S. cities between 1957 and 2012. Cluster analysis identified each article’s core rhetoric, which was classified according to sentiment and tone. Multilevel count regression models measured the use of positive and negative words regarding CWF.

Results

Media coverage more closely resembled core rhetoric used by anti-fluoridationists than the rhetoric used by pro-fluoridationists. Despite the scientific evidence, the media reports were balanced in tone and sentiment for and against CWF. However, in articles emphasizing children, greater negative sentiment was associated with CWF rejection.

Conclusions

Media coverage depicted an artificial balance of evidence and tone in favor and against CWF. The focus on children was associated with more negative tone in cities where voters rejected CWF.

Practical implications

When speaking to the media, advocates for CWF should give emphasis to benefits for children, using positive terms about dental health rather than negative terms about dental disease.

Keywords: Fluoridation, Public Health/Community Dentistry, Drinking Water, Health Promotion, Public Opinion

BACKGROUND

The dental profession and the scientific community have been united in their advocacy of community water fluoridation (CWF) for 70 years. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention named CWF among the 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century.1 Despite this widespread endorsement, the U.S. general population has remained skeptical, frequently failing to support CWF in local municipal referendums.2

Supporters and opponents of CWF make opposing claims about the health benefits and safety of CWF. Whereas advocates, such as the American Dental Association (ADA), cite its safety and effectiveness in preventing dental caries, opponents, such as the Fluoride Action Network (FAN), cast fluoride as a dangerous chemical added to the water supply. For many people, their source of information about CWF is local media reports in the weeks preceding referendum. Local media generally balance the arguments for and against government actions, known as the “balance bias” and “indexing”5 in which opposing views about contentious and emotional topics are given equal standing, as opposed to interpreting the sides and reporting which is more credible. This leaves readers to decide credibility for themselves.

We perform a quantitative analysis of text to determine whether there is bias. Does media coverage about CWF convey bias towards one of the opposing sides of the debate? Further, how does local media cover emotional topics, such as children’s health, during CWF referendums?

This study examined both historic and contemporary rhetoric concerning fluoridation that appeared prior to a CWF referendum. We did this for three cities: Portland, Oregon; Wichita, Kansas; and San Antonio, Texas. We drew on text from newspaper coverage of CWF referendums conducted over six decades, from the 1950s to 2013. We conducted clustered terms and sentiment analyses of news coverage by comparing media reports with text in documents produced by the ADA and FAN. A comparison of the clustered terms covered in the news relative to the ADA and FAN offers insight as to how the media frames CWF content relative to these opposing organizations. The sentiment analysis determines what drives positive and negative coverage of CWF.

METHODS

We analyzed 234 documents from newspapers in wide circulation in San Antonio, Portland, and Wichita (articles and editorials) covering 11 CWF referendums appearing on ballots between 1957 and 2012 (Appendix Table 1). There were 44 articles from the 2000 San Antonio referendum and 16 articles from the 1978 Portland referendum when CWF was supported. The remaining 174 articles were from referendums when CWF was rejected.

For the most recent elections (Portland, 2013; Wichita, 2012; and San Antonio, 2000), we collected documents from news sources located through searches of Google, LexisNexis, and NewsBank databases using the keyword terms “Fluoride” or “Fluoridation” and the city’s name and year of the election. For the elections that took place prior to 2000, we contacted local libraries to obtain newspaper documents. For the 1966 and 1985 San Antonio elections, the San Antonio Public Library sent scanned copies of newspaper articles from The San Antonio Express-News, The San Antonio Light, and San Antonio Register that featured the topic of fluoride in the relevant election years. To obtain newspaper articles for the 1956, 1962, 1978, and 1980 Portland elections, we identified articles of interest published in The Oregonian and Oregon Journal from the online University of Oregon Newspaper Index using the same search terms, and requested copies. For the 1964 and 1978 Wichita elections, we received copies of The Wichita Eagle newspaper on non-indexed microfilm housed at Wichita State University Libraries. To collect newspaper articles, we manually examined the microfilm and scanned articles that mentioned water fluoridation in the months before and during the election and the month during which the referendum was added to the ballot.

We conducted three analyses to gauge clustered terms, tone, and sentiment of news coverage in the three cities. We gauged the competing clustered terms that form the core rhetoric present in news coverage against the official positions of the ADA and FAN. Both organizations have news coverage and press releases about their activities and positions. The documents from both organizations reflect their unfiltered positions. We downloaded all 50 articles that the ADA6 posted, the 50 most recent articles from FAN,7 and the primary documents on both websites detailing their position on fluoridation.8,9

Statistical analysis

We conducted a hierarchical cluster analysis of the text contents and depict the results graphically, using dendrograms. The process calculates the scaled Euclidean distance between non-sparse and mostly stemmed words, grouping terms into the most parsimonious clusters by similarity.10 Dendrograms depict the core words from which other words were derived. Dendrograms also show the extent of dissimilarity of the core clusters and their ordering in relation to one other. Clusters of words branch off from each other, with words higher in the diagram being more influential and dissimilar.

We likewise analyzed text from news coverage where CWF was rejected and where CWF passed. Although cluster analysis does not employ statistical significance tests for definitive conclusions,10 the more similar news coverage terms are to the ADA or to FAN, the more in favor the topic coverage is to that organization.

We then measured the general tone of news coverage, using generic positive and negative word dictionaries.11 The positive dictionary includes 2,006 words while the negative dictionary includes 4,783. We also determine the sentiment of text through a manually created dictionary of pro- and anti-CWF words derived from ADA and FAN publications, respectively. The process involved recording words that conveyed bias to one side over the other, and then comparing the results to the dictionaries established in two previous fluoride sentiment studies.12,13 For example, pro-fluoride words spoke of the benefits of fluoride in preventing decay, while anti-fluoride words spoke of fluoride’s alleged harmful medical side effects and costs. Our primary departure from a prior study on article coverage for Portland’s CWF referendum12 is the removal of words like “children,” that anti-fluoride activists apply in the context of fluoride being harmful to children.

Using news coverage of the referendums, we modeled tone and sentiment (i.e., number of positive words, negative words, pro-fluoridation words and anti-fluoridation words) using four multilevel regression models for count data, each with random effects for city, year and media type. When the data were over-dispersed, we used a negative binomial regression model and otherwise a multilevel Poisson regression model. The first main independent variable of interest was a dichotomous indicator for CWF passage (coded 1) versus rejection (coded 0). A second independent variable measured the article’s number of references to “children”, an emotional topic. Given that most of the epidemiologic evidence showing benefits of CWF comes from studies of dental caries in children and that FAN espouses alleged side effects of fluoride on children, we expected to see an increase in non-neutral words. We also created an interaction term between references to children and CWF victory to determine if coverage of children differed concerning the positive/negative and pro/anti words. Random intercepts in the model were indicator variables for news type (article, editorial, or advertorial), year and city.

Parameter estimates from the regression models and their 95% confidence intervals were used to test for differences in CWF election coverage. Specifically, we tested whether CWF rejection was associated with topics more similar to FAN, more negative tone and anti-fluoride sentiment. We also tested whether references to children were associated with more non-neutral words in news coverage. We expected that more references to children should be associated with less negative and anti-CWF words in San Antonio in 2000, and more so with positive and pro-CWF words.

RESULTS

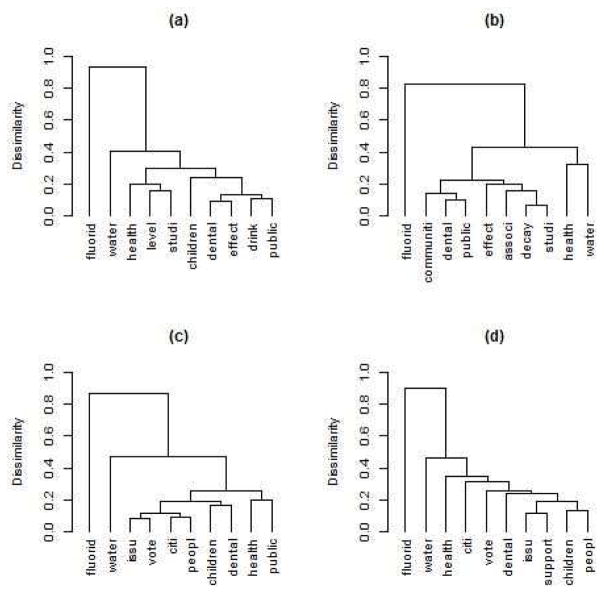

Analysis of news coverage and text attributed to the ADA and the FAN are presented in dendrograms (Figure 1). All four dendrograms reflect the core overarching cluster of fluoride, with the sub clusters more similar than dissimilar. The words that appear in all four dendrograms are “fluoride,” “water,” “health,” and “dental.” Between FAN (Figure 1a) and the ADA (Figure 1b), we find that six words are shared, with the addition of “public” and “effect.” A key substantive difference is that the word “children” is its own cluster for FAN, while the ADA focuses instead on “decay” and “prevent.” This difference fits in with anti-fluoride activist rhetoric of serious fluoride-induced diseases in children (i.e. autism), while the ADA focuses more on the benefits of fluoride preventing decay. These results do not mean that the ADA ignores children; rather, the ADA mentions children as a subcomponent of the other clusters.

Figure 1.

The news article coverage expectedly contain election related clusters, such as “vote,” “issu-,” “people,” and “citi-.” This is true for both where CWF lost and won. News articles where CWF lost (Figure 1c) share six clusters with FAN and only five with the ADA. The FAN cluster present in news coverage where CWF lost is “children.” News coverage where CWF won (Figure 1d) also has “children” as a cluster, though replaces the cluster “public” with “support.”

Although we cannot draw strong conclusions from these dendrograms alone, they suggest that news coverage slightly favors anti-fluoride topics. FAN’s focus on children makes its way into news coverage. This demonstrates that an emotional topic, which tend to induce extreme risk aversion14 among readers, is a core part of CWF coverage.

Tone and sentiment analysis

Table 1 presents the six most common words for the tone and sentiment analysis of the 234 news articles, showing some overlap between the tone and sentiment terms. However, where the tone will leave readers with a general feeling after reading a given article, the sentiment conveys the position that an article takes on the merits of CWF.

Table 1.

Six Most Frequent Terms Classified According to Tone and Sentiment Appearing in 234 News Articles

| Tone | Sentiment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Term (frequency) | Negative Term (frequency) | Pro-CWF Term (frequency) | Anti-CWF Term (frequency) |

|

|

|

||

| Support (124) | Decay (124) | Health (177) | Problem (65) |

| Benefit (85) | Problem (65) | Dental (167) | Lead (55) |

| Like (84) | Concern (52) | Decay (124) | Poison (39) |

| Safe (80) | Harm (49) | Prevent (99) | Bone (33) |

| Good (74) | Severe (44) | Cost (89) | Dose (30) |

| Work (71) | Reject (40) | Benefit (85) | Cancer (29) |

Terms in the tone and sentiment dictionaries are not mutually exclusive. Positivity or negativity of tone is classified independently of pro- or anti-CWF sentiment.

Notice that there are four combinations by tone and sentiment: positive and pro-CWF (benefit), positive and anti-CWF, negative and pro-CWF (decay), and negative and anti-CWF (problem). There are no terms that are positive in tone and anti-CWF. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind the potential differences in tone and sentiment, and how readers might remember an article given its tone and sentiment.

Count Regression Models

Table 2 presents four count regression models for the tone and sentiment of news coverage. Model 1 employs negative binomial regression while Models 2 through 4 employ Poisson regression. The Appendix provides justification for the different modeling methods.

Table 2.

Count Regression Models of News Coverage Tone and Sentiment

| Dependent variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive words | Negative words | Pro-CWF words | Anti-CWF words | ||

| Independent variable | |||||

| Referendum outcome (0= CWF rejection, 1= CWF support)) | β | 0.48 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 0.84 |

| 95% CL | (−0.40, 1.35) | (−0.29, 1.53) | (−0.44, 1.05) | (0.14, 1.55) | |

| P-value | p = 0.29 | p = 0.18 | p = 0.43 | p = 0.02 | |

| Child references (number) | β | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.51 |

| 95% CL | (0.16, 0.39) | (0.26, 0.40) | (0.23, 0.41) | (0.38, 0.64) | |

| P-value | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | |

| Interaction: Child references X referendum outcome | β | −0.18 | −0.16 | −0.07 | −0.21 |

| 95% CL | (−0.42, 0.07) | (−0.28, −0.03) | (−0.24, 0.11) | (−0.44, 0.03) | |

| P-value | p = 0.16 | p = 0.02 | p = 0.47 | p = 0.09 | |

| Intercept | β | 1.51 | 1.41 | 0.86 | −0.04 |

| 95% CL | (1.13, 1.90) | (1.00, 1.82) | (0.52, 1.20) | (−0.58, 0.50) | |

| P-value | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p = 0.89 | |

| Ob servations: # news articles | 234 | 234 | 234 | 234 | |

| Model Log Likelihood | −675.7 | −858.3 | −521.06 | −446.49 | |

CWF = community water fluoridation

β=Regression parameter estimate; 95% CL = 95% confidence limits; P-value from test of null hypothesis that β=0

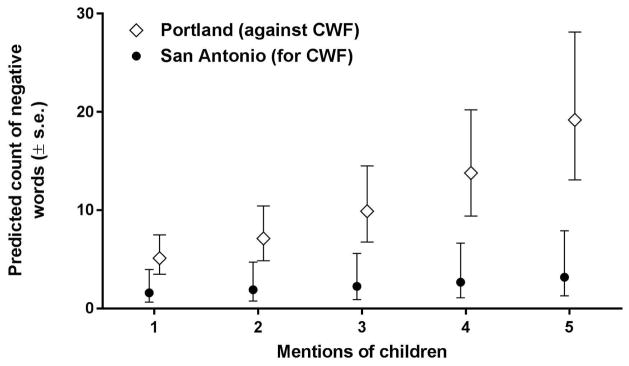

In all four models, the number of references to children exerts a positive and significant effect (p<.001). Results can be interpreted by exponentiating the coefficients to find the rate ratio. For model 1, greater reference to children increases the count of positive words on average by a factor of 1.3. The interaction between references to children and CWF victory does not reach significance in model 1. The coefficient for CWF victory is positive, though does not exert a significant effect (p = 0.29). In model 2 analyzing negative terms in news coverage, CWF victory was not a statistically significant effect, although references to children and its interaction with CWF victory was significant (p<0.01). The expected count of negative words increases by approximately 1.35 in referendums where CWF lost for every additional reference to children. However, this effect reduces to about 1.19 for CWF victory. Figure 2 illustrates the interaction by showing that negative words were associated with CWF rejection only when articles made frequent reference to children.

Figure 2.

In model 3, the number of references to children was the only feature that had a significant association with pro-CWF words, and the effect was positive. In model 4, the variable “references to children” is also significantly associated with more anti-CWF terms. Further, there is a significant (p<0.05) effect for CWF victory, indicating that where CWF won there were 2.32 times as many anti-CWF terms than where CWF lost. Like model 2, there was a positive interaction between children references and CWF victory that nearly reaches statistical significance (p=0.09). Despite the interaction effects, there is no significant difference in aggregate tone and sentiment differentiated by whether a city won or lost a CWF referendum.

DISCUSSION

There were three principal findings from the text analysis. First, news coverage of CWF reflects some evidence of a media balance bias. Second, greater reference to children is associated with an increase in non-neutral terms. Third, the extent of negative tone is more strongly associated with CWF defeat as an article’s number of references to children increases.

Our results suggest that the tone in articles is approximately balanced, with a slight favor towards pro-CWF terms than anti-CWF. However, the media balances positive with negative, and pro-CWF with anti-CWF, when children are written about. These results are consistent with complaints by scientists that journalists force a false balance of arguments, and hence generate controversy.16,17 Coverage of CWF largely appears to conform with media desires to appear balanced to the general audience and sell the news.

Among referendum items, CWF is infamous for its level of polarization despite being an established public health good. Opposition to marginal increases in public water fluoridation arose upon the inception of CWF, with accusations against fluoride focused on the theme of forced medication,12 dangerous side effects18 and contamination of natural resources.4,12,18 Due to public contention, water fluoridation is the most competitive type of referendum and receives the lowest level of support in the event of passage.19 Among the initial reasons given to CWF’s poor performance is that CWF opponents “[N]eed only to create doubt about fluoridation; they do not need to convince the electorate of all their points” (page 60, italics in original).7 The concept of doubt derailing changes to the status quo has since received wider support in research on issue framing and agenda setting; those who seek to change status quo policy need to refute the opposition and present a positive message to make clear that their alternative is superior.20,21 When anti-fluoride activists raise concerns of fluoride-induced cancer, coupled with the frame of easy opt-in to fluoride via tablets, CWF referendums can easily fail.12,18,22

In this study, the media gave similar coverage to anti-fluoride arguments and scientific evidence, especially in relation to children. Although we do not know how voters interpreted these conflicting views, the balanced yet biased coverage did not aid pro-fluoride activists.

Where CWF won might offer some insight in CWF messaging. Although mention of children drove the contentious balanced coverage, the rate at which negative and anti-CWF terms were mentioned was significantly less. When people read the news, they read less generally negative and anti-CWF coverage associated with children. Given that people often tend to forget the context of news and associate the tone of coverage with the appeal of the issue in question,2,14,23 it makes sense that more negative coverage in general might impair passage of CWF. Further, the targeted use of anti-CWF terms in relation to children may very well have associated fluoride with harm to children. Case studies conducted of fluoridation in 1985 found that positive messaging and direct outreach greatly aided in the passage of CWF.24

Given the importance of doubt in derailing CWF referendums, it is necessary to consider the messaging that voters receive from the media. If doubt is all that is needed to prevent pro-fluoridation votes, then even a few hints of anti-fluoride information may be enough to bring down CWF. Fluoride campaigns in California in the 1950s only succeeded in the event of overwhelming support for fluoride without any serious opposition.18 More recently in Portland, Oregon in 2013, even purportedly balanced coverage did not prevent a lopsided defeat for CWF.12 Established models of referendum voting demonstrate that voters vote for a change in the status quo only when they are certain that the change will result in a better outcome.20 Given that the average person does not scientifically understand fluoridation or the credibility of information sources,4,25 mixed messages that introduce even some uncertainty should be enough to lead to a rejection at the polls.

There is no easy way forward to overcome reluctance to accept CWF. One step is to start employing an easy to understand and positive message with direct outreach to voters.24 Handing out accessible information at dental offices and door-to-door would bypass the media filter and resolve confusion. While this will require resources and effort, the status quo does not appear to be working.

Strategies for Advocacy

Advocates for community water fluoridation should be conscious of the media’s tendency for “balance bias” in which equal weight is assigned to opposing views, regardless of the strength of evidence supporting those views. One way for dentists to avert the bias is by communicating directly with their patients in dental offices and the public at large at community gatherings. When messages are conveyed via the media, it is advisable to prepare accessible and non-specialized information for journalists in advance of elections. Reviews of scientist-press relations recommend establishing an early rapport with journalists in order to ensure that reporters do not falsely balance scientific and pseudo-scientific studies.16,17 A journalist covering an election with a clear understanding of the differing scientific merit of each side will be able to conduct more investigative studies as opposed to reporting on argumentum ad passions logical fallacious arguments against CWF. One specific strategy, suggested by findings from this study, is to recognize and counteract anti-CWF language as it relates to children, such as purported harmful effects of CWF for children’s health. For example, fluorides’ benefits for children can be depicted using positive terms (improving dental health) instead of negative ones (reducing tooth decay).

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UH2DE025494. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The underlying data, code, and other materials necessary to reproduce results presented in the article will be preserved and made publicly available online via the UNC Dataverse (https://dataverse.unc.edu/) hosted by the Odum Institute Data Archive at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

APPENDIX

Establishing the Document Term Matrices

We conducted the analysis via the document term matrices that we derived from the articles used in this study. All articles were copied and pasted to text documents for archive and replication purposes. We read in the articles as a corpus, where we applied standard transformations. These included removing URLs, punctuation, whitespace, and transforming all words to lower case. From there we analyzed the data and removed uninformative words and replaced synonyms with a common word. These included all synonyms of fluoride, science and children. Words that referenced locations were also removed.

For the creation of the dendrograms, we read in the top ten most frequently occurring words from the term document matrix and scaled the distance between the words based on Euclidean distance. We then normalized the distances onto a zero to one scale by dividing the distances by the maximum distance between the words. Once the distances were normalized, we plotted the results based on the average distance.

The tone and sentiment text analysis required the creation of unique cleaning profiles with the respective dictionaries attached. Other cleaning commands were the same as described above. Following the creation of document term matrices, we summed the data by column (article), and then merged the tone and sentiment counts to a single data frame by their article IDs.

Determining Count Model Fit

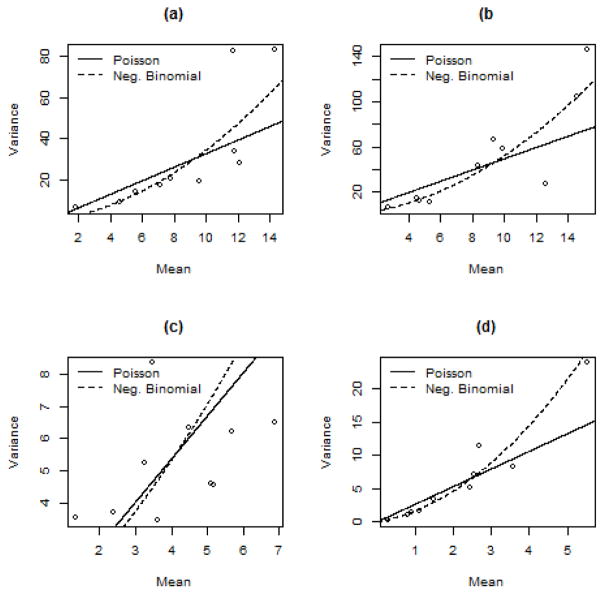

We determined the best model for tone and sentiment based on first, whether the model converged, and second, the presence of over dispersion in the data. Poisson regression assumes that the count mean and variance are equivalent.1 When this is not true, the results produced will generally be biased. Negative binomial models account for variances greater than the mean and scale the standard errors relative to the level of over dispersion. However, negative binomial models take up more degrees of freedom and can lead to inefficiency. Given that we account for three different random effects, city, election date, and media type, there is the risk of non-convergence as the model becomes impossible to compute.2 Unlike single level models, multilevel models with random effects can reduce the bias that would otherwise afflict Poisson regression models, with observation level effects eliminating all potential bias.3 We therefore seek the best unbiased model that is also computationally possible.

Figure 1 demonstrates the mean relative to the variance for all four models, fitting the data to Poisson and negative binomial lines. As can be seen in the figures, the Poisson models do a sufficient job at explaining the data up until the high mean values. It is at the higher means that the negative binomial lines adjust easier to the higher variances and account for potential bias. It would therefore be ideal to use negative binomial models. However, besides the positive count data, the models do not converge when negative binomial models are used. This is due to the random effects providing too few degrees of freedom. While unfortunate, given that the higher mean values are few in number, the Poisson multilevel models as used for models 2 – 4 offer the best, albeit, imperfect means to run our analyses.

Figure 1. Count Model Dispersion Plots.

Plot (a) is model 1 of the positive word count, plot (b) is model 2 of the negative word count, plot (c) is model 3 of the pro-CWF word count, and plot (d) is model 4 of the anti-CWF word count. All plots demonstrate the best fit lines of the multilevel Poisson models compared to the negative binomial models. For all models, the Poisson model explains most of the data up until the high mean values. Higher means are better explained by negative binomial models. However, in the data the random effects largely explained by the high mean values, and the lack of degrees of freedom lead to a failure of multilevel negative binomial models to converge. Therefore, the Poisson multilevel models explaining the data sufficiently

Appendix Table 1.

Characteristics of referendums and source of articles

| Portland, Oregon | Wichita, Kansas | San Antonio, Texas | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referendum year | 1956 | 1962 | 1978 | 1980 | 2013 | 1964 | 1978 | 2012 | 1966 | 1985 | 2000 |

| Referendum decision | Against | Against | For | Against | Against | Against | Against | Against | Against | Against | For |

| % voting in favor of fluoridation | 42% | 45% | 51% | 46% | 39% | 37% | 46% | 40% | 32% | 48% | 53% |

| Number of votes cast | 181,140 | 144,300 | 139,373 | 115,408 | 164,301 | 50,997 | 84,139 | 129,199 | 38,855 | 81,373 | 292,811 |

| Population size | 373,628 | 372,676 | 382,619 | 366,383 | 733,764 | 254,698 | 276,554 | 356,724 | 587,718 | 785,880 | 1,385,695 |

| News media type | |||||||||||

| Article | 14 | 13 | 14 | 10 | 12 | 19 | 5 | 23 | 5 | 19 | 26 |

| Editorial | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 12 | 6 | 18 |

| Advertisement | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 15 | 15 | 16 | 12 | 24 | 27 | 10 | 25 | 21 | 25 | 44 |

Bibliography

- 1.Long S. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1997. pp. 217–250. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolker BM, Brooks ME, Clark CJ, Geange SW, Poulsen JR, Stevens MHH, White JSS. Generalized linear mixed models: a practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2009;24:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison XA. Using observation level random effects to model overdispersion in count data in ecology and evolution. [Accessed July 29, 2017];PeerJ. 2014 2 doi: 10.7717/peerj.616. Available at http://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

Disclosure. None of the authors reported any discloures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Ten great public health achievements--United States, 1900–1999. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(12):241–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochschild JL, Einstein KL. Do facts matter? Information and misinformation in American politics. Polit Sci Q. 2015;130(4):585–624. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metz AS. An analysis of some determinants of attitude toward fluoridation. Soc Forces. 1966;44(4):477–484. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin B. The sociology of the fluoridation controversy: A reexamination. Sociol Q. 1989;30(1):59–76. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett WL. Toward a theory of press-state relations in the United States. J Commun. 1990;40(2):103–127. [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Dental Association. [Accessed Apr. 11, 2017];ADA news on fluoridation. Available at: http://www.ada.org/en/public-programs/advocating-for-the-public/fluoride-and-fluoridation/ada-fluoridation-recent-news.

- 7.Fluoride Action Network. Fluoride articles. [Accessed April 11, 2017];Mercola. Available at: http://fluoride.mercola.com/

- 8.American Dental Association. Fluoridation facts. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; Jul, 2005. [Accessed July 20, 2016]. Available at: http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Member%20Center/FIles/fluoridation_facts.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connett P. 50 reasons to oppose fluoridation. Birmingham, NY: Fluoride Action Network; Sep, 2012. [Accessed July 20, 2016]. Available at: http://fluoridealert.org/articles/50-reasons/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mouchet M, Guilhaumon F, Villéger S, Mason NWH, Tomasini J-A, Mouillot D. Towards a consensus for calculating dendrogram-based functional diversity indices. Oikos. 2008;117(5):794–800. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu M, Liu B. Mining opinion features in customer reviews. Paper presented at: 19th National Conference on Artificial Intelligence; July 27, 2004; San Jose, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bianchi A, Bergren MD, Lewis PR. Portland water fluoridation: A newspaper analysis. Public Health Nurs. 2017;34(2):152–165. doi: 10.1111/phn.12284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard A. Fluoride in the media: A review of newspaper articles from 1999 to 2009. DentUpdate. 2011;38(2):86–92. doi: 10.12968/denu.2011.38.2.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hetherington MJ. Why trust matters: Declining political trust and the demise of American liberalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hlavac M. stargazer: Well-formatted regression and summary statistics tables. [Accessed July 20, 2016];R package version 5.2. 2015. Available at: http://cran.r-project.org/package=stargazer.

- 16.Dean C. Am I making myself clear? A scientist’s guide to talking to the public. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baron N. Escape from the ivory tower: A guide to making your science matter. 2. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mueller JE. The politics of fluoridation in seven California cities. West Polit Q. 1966;(1):54–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hahn H. Voting in Canadian communities: A taxonomy of referendum issues. Can J Polit Sci. 1968;1(4):462–469. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riker WH, Calvert RL, Mueller JE, Wilson RK. The strategy of rhetoric: Campaigning for the American Constitution. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1996. p. 283. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hänggli R, Kriesi H. Political framing strategies and their impact on media framing in a Swiss direct-democratic campaign. Polit Commun. 2010;27(2):141–157. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scism TE. Fluoridation in local politics: Study of the failure of a proposed ordinance in one American city. Am J Public Health. 1972;62(10):1340–1345. doi: 10.2105/ajph.62.10.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berinsky AJ. Rumors and health care reform: Experiments in political misinformation. Br J Polit Sci. 2015;47(02):241–262. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Margolis FJ, Cohen SN. Successful and unsuccessful experiences in combating the antifluoridationists. Pediatrics. 1985;76(1):113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gans HJ. A study of CBS Evening News, NBC Nightly News, Newsweek, and Time. 2. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press; 2004. Deciding what’s news. [Google Scholar]