Abstract

Introduction

Oral submucosal fibrosis (OSMF) is a chronic debilitating fibrotic disease of the oral cavity and is a serious health hazard in south Asia and, increasingly, the rest of the world. The molecular basis behind various treatment modalities to treat OSMF still remains unclear. In this study, we have investigated the in vitro ability of the buccal mucosal cells to reduce the proliferation of the fibroblasts of the fibrotic area in co-culture of cells and also at the molecular levels to reduce the level of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in the OSMF fibroblasts (SMF-F).

Materials and Methods

The study compares isolation, morphological and proliferation kinetics of SMF-F and BMF cells with and without co-culturing with BMEs. In addition, we have compared the mRNA expression levels of CTGF in SMF-F co-cultured BME and non-co-cultured SMF-F cells using validated real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) method.

Results

The basic morphological characteristics of SMF-F were similar to BMF, but the former cells had higher proliferation rate in early passages compared to late passage state. We also observed that the CTGF expression levels in SMF-F under co-culture conditions of BME were consistently and significantly downregulated in all four different SMF-F-derived cells from four different patients.

Conclusion

Rapid proliferation and collagen synthesis in SMF-F as against BMF cells are the factors that confirm the innate nature of fibrosis fibroblasts (SMF-F). Further, the CTGF expression level in SMF-F was significantly suppressed by BME in co-culture conditions against controls (BMF). Considered together, this suggests that the cell therapeutic candidate of BME could be used in treating OSMF.

Keywords: Buccal epithelial cells, Connective tissue growth factor, Fibroblasts, Oral submucosal fibrosis

Introduction

Oral submucosal fibrosis (OSMF) is a chronic and complex debilitating disease of the oral cavity, that extends to the oropharynx, progressively increasing fibrosis, epithelial dysplasia [1] and higher incidence of leukoplakia [1, 2]. In the later stages of the disease, trismus (limited mouth opening) and severe scarring are the norm [3]. While OSMF was earlier confined to Indian subcontinent and nearly 5 million cases have been reported [4–6], it has now spread to Asian population of the UK, the USA and other developed countries and is a global health problem. The empirical methodology of treatment exists because of multi-factorial aetiopathogenesis like betel nut chewing, genetics, nutrition deficiencies, and immunological processes. The betel quid chewers alone constitute about 600 million people worldwide [7]. The main aetiological feature of the inflammatory fibrotic condition in OSMF is induced by arecoline, an alkaloid found in areca nut [8]. The increased lysyl oxidase activity induced by arecoline increases the collagen production by SMF-F with reduced collagen degradation [9]. Activation of the signalling pathway of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signalling also contributes to high collagen synthesis. The cascading event enhances elevated expression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and downregulation of BMP-7 in SMF-F [10, 11].

TGF-β inhibits the degradation of collagen by inducing the activity of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase gene (TIMPs) and thus creating an oversynthesis of collagen via CTGF pathway [11]. The TGF-β1-induced CTGF plays a central role in inducing the myofibroblastic phenotype, thus resulting in higher proliferation and in turn higher collagen synthesis under various fibrotic conditions. Therefore, the CTGF suppression in SMF-F forms the major therapeutic candidate for anti-fibrotic indications. Hence, the present study focuses on comparative cell culture characteristics in terms of morphology, growth kinetics of normal fibroblast (BMF) and fibrosis fibroblast (SMF-F) derived from buccal mucosal cells. This assumes clinical significance along with the examination of efficacy of buccal mucosal epithelial cells to suppress CTGF in SMF-F cells under co-culture conditions.

Materials and Methods

Cell Sourcing

Informed consents were obtained from patients (aged above 52 years) undergoing reconstructive surgery in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Rangadore Memorial Hospital, Bangalore, after approval of the institutional ethics committee. An experienced oral surgeon performed the biopsies from the buccal mucosa under appropriate asepsis and anaesthesia. A small segment of the buccal mucosa from the patients (n = 4) and controls (n = 4) was used to derive the submucous fibrosis fibroblast (SMF-F) and normal fibroblast—the buccal mucosa fibroblast (BMF), respectively. Patients undergoing removal of impacted wisdom teeth served as controls for excision of mucosa from a part of the incision placed to perform the procedure.

Isolation and Cell Culture

The BME cells were isolated using dual enzymatic steps consisting of dispase II (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA, USA) treatment to separate epithelial cell sheets, followed by collagenase type IV (Life technologies, Waltham, MA, USA) to get the suspended cells. The isolated cells (n = 1) were cultured in Epi-Life complete medium (Life Technologies, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions and subcultured till passage 2 (P2) for further use in co-culture experiments. The SMF-F and BMF cells were isolated from the biopsy samples by collagenase IV digestion and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). The cells were grown at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator, cryopreserved at P2 and further passaged to P7. The morphological changes observed during cultivation of the cells were recorded using a phase-contrast inverted microscope (Olympus INV, Morristown, New Jersey, USA) at 280× magnification.

Proliferation Kinetics

The proliferation kinetics of SMF-F and BMF cells were studied up to P7 using initial seeding density of 5000 cells per cm2. The cumulative population doublings (CPDs) and population doubling time (PDT) were calculated following Yuan et al. [4, 12].

Co-culture Experiments

The 0.3 × 106 cells of SMF-F were seeded in 6-well plates, and 0.3 × 106 of BME cells were separately seeded in polyurethane cell culture inserts (ThinCert™ Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Germany) of 0.4-µM pore size. Wells containing SMF-F and BMF cells alone at the same seeding density were used as controls. The cell cultures were prepared in separate compartments (inserts and wells) a day before the co-culture. DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS was used as the standard culture medium for all the cell types prior to induction. The following day, the co-culture was induced by placing the inserts containing BME onto SMF-F wells. The medium used during the induction phase was DMEM supplemented with 0.5% FBS, and the cells were confluent in inserts and wells under these conditions. Co-culture of BME and SMF-F cells was continued for additional 24 h, and the respective fibroblasts was analysed for residual CTGF levels by QPCR. Experiments were done in four batches in triplicate, unless mentioned otherwise.

qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from SMF-F and BME/SMF-F cells using TRIzol™ Plus RNA Purification Kit (Invitrogen, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions, and the RNA concentration was measured using NanoDrop (Thermoscientific, CA, USA). All the RNA samples were treated with HL-ds DNase from (ArticZymes, Norway) to remove the contaminating genomic DNAs and then transcribed to cDNA using SuperScript III Platinum one-step qRT-PCR Kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Briefly, the RT reaction was carried out in a final volume of 40 µl containing 1X SuperScript Master Mix, Oligo (dT) (Thermo Scientific, USA), and 500 ng of total RNA. Reactions were carried out at 50 °C for 50 min followed by incubation at 75 °C for 15 min to inactive the residual RT activity. Three microlitres of the prepared cDNA was taken as a template for qPCR of human GAPDH gene using GAPDH-specific primers. Based on the copy numbers of GAPDH content in the cDNA samples, the total cDNA was normalized and subjected to qPCR for human CTGF gene using CTGF-specific primers.

Quantitative PCR was performed in Qiagen qPCR machine (Qiagen, Germany). The conditions for qPCR were initial denaturation 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 57 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s. At the end of the PCR cycles, the melt curve was analysed for examining specific amplification of the product of interest. The experiments were done in four batches of fibrous fibroblasts in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

All values were expressed as mean ± SEM (standard error of mean), and the data were analysed by Student’s t test and ANOVA using GraphPad Prism (version 5, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant between the groups tested (***P < 0.001).

Results

Isolation and Cell Culture

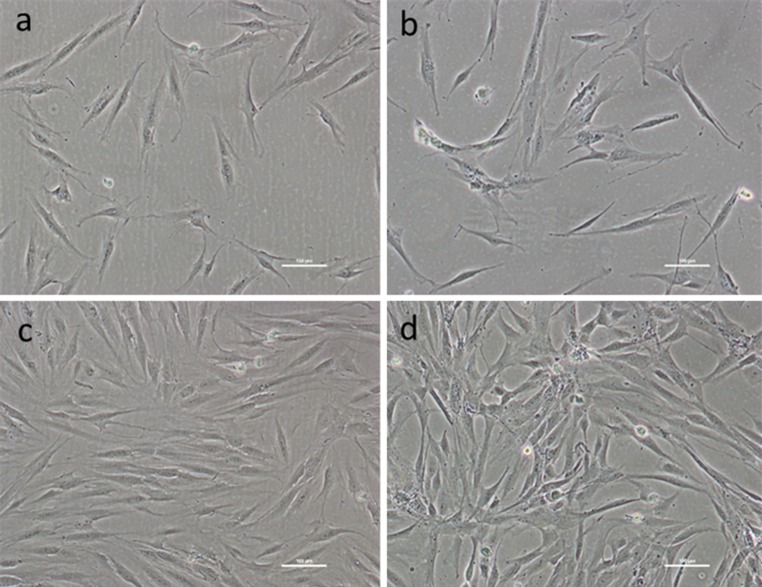

The biopsy samples of BMF and SMF-F cells from different patients were shipped to the cell culture manufacturing facility of SRTE, Bangalore, India, in sterile transportation container containing transportation media in cold (2–8 °C). The seeding density at passage 0 (P0) of BMF and SMF-F isolated cells was 50,000 cells per cm2 and 5000 per cm2 at subsequent passages. It was observed that BMF in early passages attained 80–90% confluency at a slower rate than the rate of growth of SMF-F cells in early passages. The PreP0 cell yield of BMF and SMF-F cells was 0.75 ± 0.28 and 0.44 ± 0.15 million per 9.6 cm2, respectively. Although BMF and SMF-F cells showed general nature of spindle-shaped cells with tapering ends, the SMF-F cultures contained relatively larger number of small spindle-shaped cells compared to BMF cells (Fig. 1). On the other hand, BMF cells in early passages at subconfluent stage looked uniform, while SMF-F was slightly pleomorphic with hill and valley morphology [12]. Similarly, the morphology, growth and functional characteristics of BME cells were also studied [13].

Fig. 1.

Comparative morphological characteristics of early (a, b) and late confluency (c, d) stage of buccal mucosal normal fibroblast (BMF) cells—(a, c); oral submucosal fibrosis fibroblast (SMF-F) (b, d) at passage 2 (P2). Scale bar ~ 100 µm

Proliferation Kinetics

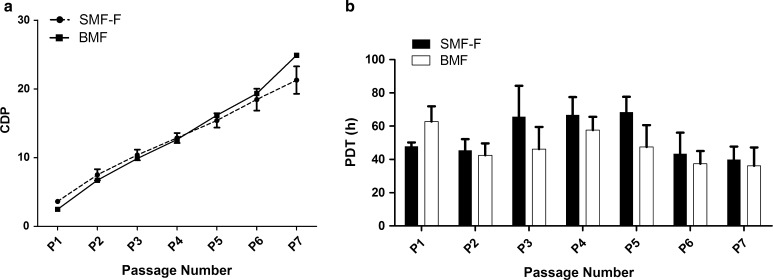

The proliferation kinetics of BMF and SMF-F cells across passages P1–P7 showed no significant difference in terms of CPD as evident from growth kinetics plots (Fig. 2a). However, SMF-F cells in early passages showed prominently higher CPD forming the crossover at P4. Similarly, SMF-F cells in the early passage have substantially lower PDT compared to BMF (Fig. 2b). Overall, SMF-F cells showed differential dynamics in growth kinetics at early- and late-stage passages and reached a similarity in PDT at P6 and P7.

Fig. 2.

Comparative proliferation kinetics profiles of BMF and SMF-F. a Cumulative population doublings (CPDs), b Population doubling time (PDT)

Co-culture Experiments

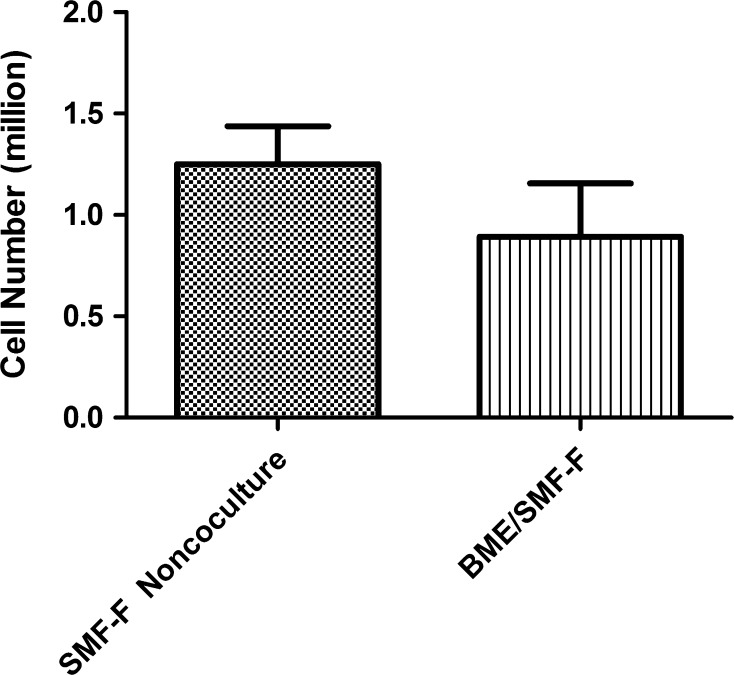

The fibroblast inhibition by proliferating BMEs during co-culture induction was evident when compared to non-co-cultured SMF-F cells (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of cell number in BME co-cultured fibroblast cells (BME/SMF-F) and non-co-cultured SMF-F cells

qPCR

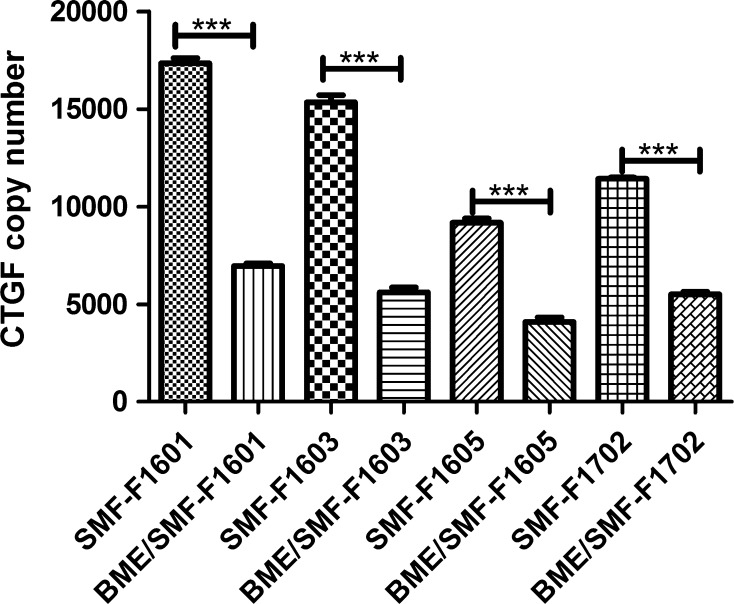

The comparative CTGF expression from qPCR of non-co-cultured SMF-F and co-cultured BME/SMF-F cells was significantly suppressed by BME as evident by the decreased levels of CTGF copy numbers in BME/SMF-F cells of all the four sets of samples (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

BME downregulates twofold to threefold of CTGF expression in co-cultured BME/SMF-F compared to the non-co-cultured SMF-F

Discussion

OSMF is a progressive and potentially malignant fibrotic disease occurring due to increased addiction of various forms of chewing areca nuts. The incidence of this clinical condition is increasing from 0.25 million cases in 1980 to ~ 5 million cases in 2002 in the Indian subcontinent [5, 6]. The precise aetiology and pathogenesis for OSMF condition are not clearly understood as many causative and contributing agents are involved like local irritants, nutritional deficiency, smoking, autoimmunity, and genetic predisposition [14]. The multiple contributing agents have led to multiple management modalities to reverse the existing fibrosis [15]. The corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid, enzymes such as collagenase, hyaluronidase, chymotrypsin and minerals, vitamins are mostly palliative for the treatment of OSMF, while use of drugs like IFN gamma that have shown promise in the improvement in mouth opening needs further clinical validation [16]. The currently available non-surgical treatment forms for OSMF are inadequate to reverse the established fibrosis, and hence, cell-based therapies assume critical significance. In an earlier study, the authors have demonstrated the molecular basis of anti-fibrotic activity of BME cells using urethral stricture fibroblasts. The data here reinforce the conclusion of the previous report. As a logical step forward, in the current study, we have demonstrated that the co-cultured BME with SMF-F significantly reduces the CTGF levels than non-co-cultured SMF-F cells, indicating the possible role of BME cells in reducing fibrosis.

Isolation of BMF and SMF-F cells from biopsy tissues reveals a distinct decrease in fibroblast in SMF-F cells in comparison with BMF cells, and this may be due to accumulation and the gradual disintegration of senescent fibroblasts supporting the reports of Pitiyage et al. [17].

Although SMF-F and BMF cells meet the general spindle-shaped morphological characteristics (Fig. 1), they contain a subpopulation of fibroblasts-like small spindle-shaped cells of non-uniform nature in SMF-F cells too. The stated morphological features of SMF-F correlate with the pleomorphic nature in SMF-F as reported by Mathew et al. [18]. This pleomorphic nature of culture may be due to the lack of natural defence and inherently irreversible DNA double-strand breaks [17, 19].

The early passages of SMF-F cells showed prominently higher proliferation as evident by higher CPDs and lower PDT (Fig. 2), and the possible reason for the activation of prominent proliferation in early passage is probably due to induction of TGF beta pathway by a causative agent of fibrosis [10]. Since CTGF is one of the primary early targets of TGF beta pathway, we used the early passage cells of SMF-F to examine the effect of such cells on CTGF levels under co-culture conditions. Further, increased expression of CTGF is one of the well-known factors in several fibrotic diseases, besides increased expression of TGF beta and VEGF [20–24].

Epithelial cell-conditioned medium inhibits the fibroblasts growth [25] [8], and we have shown earlier that urethral stricture fibroblast when co-cultured with BME results in downregulation of CTGF by BME [26]. In this present study, we have used buccal mucosal epithelial cells and have observed suppression of CTGF by these cells when co-cultured with fibrous fibroblasts cells. This supports the reports of fibroblast suppression by keratinocytes in co-culture conditions by Werner et al. [27]. The current study also suggesting downregulation of CTGF by BME cells appears to be a novel method for treating OSMF.

Current study is limited by small number of samples studied. We have used the CTGF as one of the marker for fibrosis, though there are multiple agents involved in wound healing and fibrosis. Fibrosis fibroblast may be at different periods of healing and may react differently to the inhibition by BME cells. In spite of all these limitations, this study seems to indicate significant reduction in CTGF by the potent BME cells on co-culture.

Conclusions

Detection of differential expression of CTGF in BMF and SMF-F is the primary diagnostic driver, although it is increasingly important to know the other variable factors that play an intrinsic role in reversing the fibrosis. The CTGF suppression in SMF-F cells by the first-of-its-kind study demonstrates this at cellular and molecular levels. The BME cells appear as potent cell therapeutic agents to direct the reversal of established fibrosis. Hence, further efforts focusing on dosing regimen and cell delivery methodologies for better tissue regeneration to treat the OSMF would be useful.

Acknowledgement

SRTE is fully supported by Sri Sringeri Sharada Peetam.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The author discloses no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Shirani S, Kargahi N, Razavi SM, Homayoni S. Epithelial dysplasia in oral cavity. Iran J Med Sci. 2014;39:406–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surej KL, Kurien NM, Sakkir N. Buccal fat pad reconstruction for oral submucous fibrosis. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2010;1:164–167. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.79222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta SK, Rana AS, Gupta D, Jain G, Kalra P. Unusual causes of reduced mouth opening and it’s suitable surgical management: our experience. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2010;1:86–90. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.69150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bari S, Metgud R, Vyas Z, Tak A. An update on studies on etiological factors, disease progression, and malignant transformation in oral submucous fibrosis. J Cancer Res Ther. 2017;13:399–405. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.179524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiu CJ, Chang ML, Chiang CP, Hahn LJ, Hsieh LL, Chen CJ. Interaction of collagen-related genes and susceptibility to betel quid-induced oral submucous fibrosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:646–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox SC, Walker DM. Oral submucous fibrosis: a review. Aust Dent J. 1996;41:294–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1996.tb03136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta PC, Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of areca nut usage. Addict Biol. 2002;7:77–83. doi: 10.1080/13556210020091437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prabhu RV, Prabhu V, Chatra L, Shenai P, Suvarna N, Dandekeri S. Areca nut and its role in oral submucous fibrosis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2014;6:e569–e575. doi: 10.4317/jced.51318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang SF, Hsieh YS, Tsai CH, Chen YJ, Chang YC. Increased plasminogen activator inhibitor-1/tissue type plasminogen activator ratio in oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Dis. 2007;13:234–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan I, Kumar N, Pant I, Narra S, Kondaiah P. Activation of TGF-beta pathway by areca nut constituents: a possible cause of oral submucous fibrosis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e51806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ihn H. Pathogenesis of fibrosis: role of TGF-beta and CTGF. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2002;14:681–685. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200211000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan H, Kaneko T, Matsuo M. Relevance of oxidative stress to the limited replicative capacity of cultured human diploid cells: the limit of cumulative population doublings increases under low concentrations of oxygen and decreases in response to aminotriazole. Mech Ageing Devel. 1995;81:159–168. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(95)01584-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottipamula S, Saraswat SK, Sridhar KN. Comparative study of isolation, expansion and characterization of epithelial cells. Cytotherapy. 2017;19:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arakeri G, Rai KK, Hunasgi S, Merkx MAW, Gao S, Brennan PA. Oral submucous fibrosis: an update on current theories of pathogenesis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46:406–412. doi: 10.1111/jop.12581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arakeri G, Rai KK, Boraks G, Patil SG, Aljabab AS, Merkx MAW, et al. Current protocols in the management of oral submucous fibrosis: an update. J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46:418–423. doi: 10.1111/jop.12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chole RH, Gondivkar SM, Gadbail AR, Balsaraf S, Chaudhary S, Dhore SV, et al. Review of drug treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitiyage GN, Slijepcevic P, Gabrani A, Chianea YG, Lim KP, Prime SS, et al. Senescent mesenchymal cells accumulate in human fibrosis by a telomere-independent mechanism and ameliorate fibrosis through matrix metalloproteinases. J Pathol. 2011;223:604–617. doi: 10.1002/path.2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathew DG, Skariah KS, Ranganathan K. Proliferative and morphologic characterization of buccal mucosal fibroblasts in areca nut chewers: a cell culture study. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:879. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.94693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rehman A, Ali S, Lone MA, Atif M, Hassona Y, Prime SS, et al. Areca nut alkaloids induce irreparable DNA damage and senescence in fibroblasts and may create a favourable environment for tumour progression. J Oral Pathol Med. 2016;45:365–372. doi: 10.1111/jop.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abrahams AC, Habib SM, Dendooven A, Riser BL, van der Veer JW, Toorop RJ, et al. Patients with encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis have increased peritoneal expression of connective tissue growth factor (CCN2), transforming growth factor-beta1, and vascular endothelial growth factor. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Jian Z, Yang ZY, Chen L, Wang XF, Ma RY, et al. Increased expression of connective tissue growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta-1 in atrial myocardium of patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Cardiology. 2013;124:233–240. doi: 10.1159/000347126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng YH, Tian C, Liu L, Wang L, Chang Q. Elevated expression of connective tissue growth factor, osteopontin and increased collagen content in human ascending thoracic aortic aneurysms. Vascular. 2014;22:20–27. doi: 10.1177/1708538112472282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mize TW, Sundararaj KP, Leite RS, Huang Y. Increased and correlated expression of connective tissue growth factor and transforming growth factor beta 1 in surgically removed periodontal tissues with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2015;50:315–319. doi: 10.1111/jre.12208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang P, Shi M, Wei Q, Wang K, Li X, Li H, et al. Increased expression of connective tissue growth factor in patients with urethral stricture. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2008;215:199–206. doi: 10.1620/tjem.215.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nath N, Saraswat SK, Jain S, Koteshwar S. Inhibition of proliferation and migration of stricture fibroblasts by epithelial cell-conditioned media. Indian J Urol. 2015;31:111–115. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.152809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gottipamula S, Ashwin K, Saraswat K, Sundarrajan S, Das M. Co-culture of Buccal Mucosal Epithelial Cells Downregulate CTGF Expression in Urethral Stricture Fibroblasts. J Stem Cells Clin Pract. 2017;1:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Werner S, Krieg T, Smola H. Keratinocyte-fibroblast interactions in wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:998–1008. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]