Abstract

A patient with a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm (CAP) presented to the emergency department with upper abdominal and back pain. The patient also had clinical signs of sepsis. CT revealed gallstones with acute suppurative cholecystitis with a gallbladder perforation. In addition, a CAP was also suspected and subsequently diagnosed on CT angiography. The pseudoaneurysm was treated with embolisation and a cholecystostomy was performed for the gallbladder perforation. Following her acute admission, the patient underwent an elective cholecystectomy and made a good recovery post surgery.

Keywords: biliary intervention, general surgery

Background

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm (CAP) is a rare condition, and around 25 cases have been previously described in the literature.1

The main causes include acute cholecystitis and iatrogenic injury following cholecystectomy. With respect to cholecystectomy-related injury, patients can present acutely a few months following their procedure. In addition, vascular malformation and tumour involvement have also been described.2

Patients with CAP tend to present as an emergency admission and the diagnosis is usually achieved by CT angiography (CTA).3 We present a case of CAP secondary to cholecystitis presenting as an acute admission and its subsequent management.

Case presentation

A 25-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with upper abdominal and back pain, and vomiting. The patient also had clinical symptoms and signs of sepsis. There was no significant medical history.

Physical examination revealed a soft abdomen with right upper quadrant tenderness. However, the patient had fever, tachycardia and low blood pressure.

Laboratory analysis revealed an increased white cell count with a haemoglobin level within normal range.

Following resuscitation, a CT revealed acute suppurative cholecystitis with a perforation of the gall bladder (figure 1). Gallstones were also noted. In addition, a CAP was also suspected. A subsequent CTA confirmed the diagnosis of CAP (figure 2).

Figure 1.

CT abdomen with contrast showing the cystic artery pseudoaneurysm.

Figure 2.

CT angiography showing the cystic artery pseudoaneurysm.

Due to the fact the patient presented with sepsis and had unstable observations (tachycardia and low blood pressure), a decision to embolise the CAP and drain the perforated gall bladder was made. The rationale behind this decision was that a cholecystostomy would assist in treating the underlying sepsis and embolisation of the pseudoaneurysm would prevent haemorrhage. As part of the patient’s subsequent definitive management plan, an interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy would be performed.

Arterial embolisation was performed by the interventional radiologist on-call (figures 3 and 4). The cystic artery was occluded using 3 mm×5 mm AZUR Hydrocoil and Histoacryl glue/Lipiodol (1:8). In addition, a radiologically guided cholecystostomy drain, via a transperitoneal approach, was inserted into the perforated gall bladder.

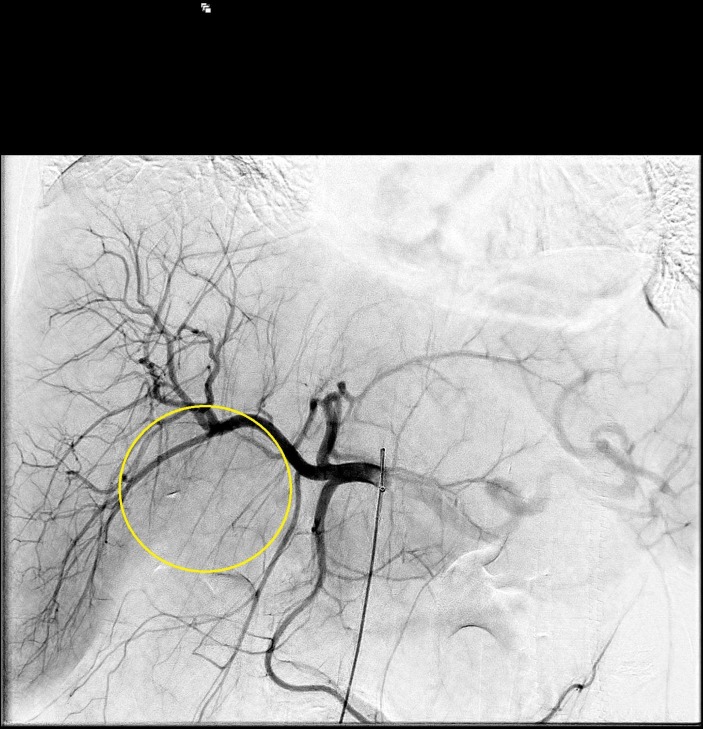

Figure 3.

Angiography showing the cystic artery pseudoaneurysm pre-embolisation.

Figure 4.

Angiography showing the cystic artery pseudoaneurysm postembolisation (disappeared).

The patient made a good recovery and was subsequently discharged home after 12 days and underwent an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Investigations

CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast

CTA.

Differential diagnosis

acute cholecystitis

perforated gastric/duodenal ulcer

acute appendicitis.

Treatment

embolisation of the CAP

cholecystostomy

elective cholecystectomy.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient made a good recovery following arterial embolisation of the CAP and percutaneous cholecystostomy.

She was discharged with the cholecystostomy drain in situ, and an interval tubogram demonstrated no obstruction in the common bile duct. The drain was removed following this procedure. The patient recently underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy and made an uneventful recovery post surgery.

Discussion

Cystic artery aneurysm is a rare condition, with the majority of cases being pseudoaneurysms.3 The most common underlying aetiology of CAP is secondary to cholecystectomy-related injury. Other reported causes include an intra-abdominal inflammatory process such as cholecystitis or pancreatitis and liver trauma.4 5 Although the underlying mechanism of laparoscopic cholecystectomy-related pseudoaneurysm formation is unclear, it is thought that these injuries occur as a result of direct injury, diathermy thermal transmission through the applied surgical clips and/or bile leakage.6 The presence of bile around the portal triad and surrounding infection is thought to weaken and cause erosion of the arterial wall, leading to pseudoaneurysm formation.7 In this case, the CAP was probably caused by surrounding inflammation around the portal triad secondary to cholecystitis. The subsequent perforation of the gall bladder resulting in bile leakage and infection could have eroded the vessel walls of the cystic artery and led to the aneurysm formation.

CAP frequently present with bleeding, usually in the form of haemobilia.8 There have also been cases where patients have presented with haematemesis and/or melaena.9 Clinical symptoms including nausea, vomiting and vague abdominal pain are also a presenting feature in the early stage of presentation. It is crucial to diagnose this condition, and in the majority of reported cases the diagnosis was achieved with a CTA.10

Because of the rarity of this disease, there are currently no guidelines on the management of this condition. Nevertheless, besides identifying the presence of CAP, it is also important to treat the underlying cause, in particular if the patient presents with sepsis. Fluid resuscitation and antibiotic therapy should be part of the initial management. Blood transfusion is rarely required in the early stage of presentation.

There are two options to treat this condition: (1) proceed to cholecystectomy or (2) arterial embolisation prior to cholecystectomy. The treatment choice should be dependent on the patient’s clinical presentation. Due to the risk of rupture, arterial embolisation of the CAP prior to cholecystectomy is thought to be the preferred pathway of treatment.11 However, this treatment may not be possible due to hepatic arterial abnormalities12 or the availability of this service.

Definitive management of these cases is cholecystectomy if the patient is fit for surgery. This can be considered during the acute presentation. However, if the patient is septic and has unstable observations, arterial embolisation of the pseudoaneurysm and a cholecystostomy are an effective ‘bridging’ treatment of this condition prior to cholecystectomy.

Learning points.

CT scan is an important investigation for young patients presenting with indeterminate sudden onset of severe abdominal pain.

Early intervention of pseudoaneurysms, including cystic artery pseudoaneurysm (CAP), is indicated to prevent rupture and bleeding.

Arterial embolisation of CAP is an effective treatment to prevent and control bleeding, and also enables the patient to recover from the acute presentation until their definitive treatment (cholecystectomy) is performed.

Footnotes

Contributors: MSK: surgical registrar who was responsible for the treatment and follow-up of the case, and he is the primary author. AA: surgical registrar and helped with the writing. YH: radiology consultant who participated in the treatment of the case and provided the needed pictures. DG: the treating consultant of the case and the supervisor of the writing of the case report.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Loizides S, Ali A, Newton R, et al. Laparoscopic management of a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm in a patient with calculus cholecystitis. Int J Surg Case Rep 2015;14:182–5. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng W, Yue D, ZaiMing L, et al. Hemobilia following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: computed tomography findings and clinical outcome of transcatheter arterial embolization. Acta Radiol 2017;58:46–52. 10.1177/0284185116638570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nkwam N, Heppenstall K. Unruptured Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery associated with acute calculus cholecystitis. J Surg Case Rep 2010;2010:4 10.1093/jscr/2010.2.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimada K, Sakamoto Y, Esaki M, et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery associated with xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Dig Surg 2008;25:8–9. 10.1159/000114194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed I, Tanveer UH, Sajjad Z, et al. Cystic artery pseudo-aneurysm: a complication of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Br J Radiol 2010;83:e165–e167. 10.1259/bjr/34623636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart BT, Abraham RJ, Thomson KR, et al. Post-cholecystectomy haemobilia: enjoying a renaissance in the laparoscopic era? Aust N Z J Surg 1995;65:185–8. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1995.tb00604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagiwara A, Tarui T, Murata A, et al. Relationship between pseudoaneurysm formation and biloma after successful transarterial embolization for severe hepatic injury: permanent embolization using stainless steel coils prevents pseudoaneurysm formation. J Trauma 2005;59:49–55. 10.1097/01.TA.0000171457.18637.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saluja SS, Ray S, Gulati MS, et al. Acute cholecystitis with massive upper gastrointestinal bleed: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol 2007;7:12 10.1186/1471-230X-7-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrou A, Brennan N, Soonawalla Z, et al. Hemobilia due to cystic artery stump pseudoaneurysm following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: case presentation and literature review. Int Surg 2012;97:140–4. 10.9738/CC52.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machida H, Ueno E, Shiozawa S, et al. Unruptured pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery with acute calculous cholecystitis incidentally detected by computed tomography. Radiat Med 2008;26:384–7. 10.1007/s11604-008-0243-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hague J, Brennand D, Raja J, et al. Cystic artery pseudoaneurysms in hemorrhagic acute cholecystitis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2010;33:1287–90. 10.1007/s00270-010-9861-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sibulesky L, Ridlen M, Pricolo VE. Hemobilia due to cystic artery pseudoaneurysm. Am J Surg 2006;191:797–8. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]