Abstract

We present a case of a 39-year-old man who presented with chronic bilateral upper extremity pain associated with innumerable angiomyolipomas that developed 5 years after a motor vehicle accident involving his upper extremities. Our case notes the rare nature of painful adipose tissue deposits and the diagnostic challenges.

Keywords: dermatology, musculoskeletal and joint disorders, skin, pain (neurology)

Background

Adiposis dolorosa (Dercum’s disease) is a rare, sporadic disease characterised by generalised obesity with pronounced pain in the adipose tissue.1 Neurologist Francis Dercum first described the condition in 1888,2 characterising it as painful adipose deposits associated with obesity and psychiatric disturbances. Adiposis dolorosa should be diagnosed through physical examination and a comprehensive exclusion of alternative diagnoses, especially as varied unusual signs have been described.1 A high index of suspicion is needed for appropriate diagnosis as the symptomatology overlaps with numerous common and uncommon diseases.

Case presentation

A 39-year-old Caucasian man with obesity and chronic lower back pain presented in consultation to the pain management service. Further investigation disclosed that the nodules and upper extremity pain had started in the same region as a traumatic injury sustained from a motorcycle accident about 5 years prior. Previously, he described a suboptimal response to multiple therapeutic interventions including narcotics, acupuncture and carpal tunnel release surgery.

On initial evaluation, he was being prescribed amitriptyline, baclofen, valsartan, gabapentin, meclizine, metformin, morphine extended release (ER), oxycodone-acetaminophen, pantoprazole, tizanidine and triamterene. With his current regimen, he estimated that he had only a 30% improvement in his pain and level of functioning.

His medical history included hypertension, type I2 diabetes mellitus, fibromyalgia, chronic lower back pain and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. He had no significant family history including no history of drug or alcohol abuse. He was unemployed without any litigation or compensation issues related to his pain.

On examination, he was severely obese with a body mass index of 47.25 and was found to have numerous diffuse palpable tender subcutaneous nodules in the upper extremities. He had mild weakness of the palmar adductors and dorsal abductors with otherwise preserved upper and lower extremity strength. He was observed to have no dystrophic skin or nail changes, differential skin colouration or temperature or differential sweating.

Investigations

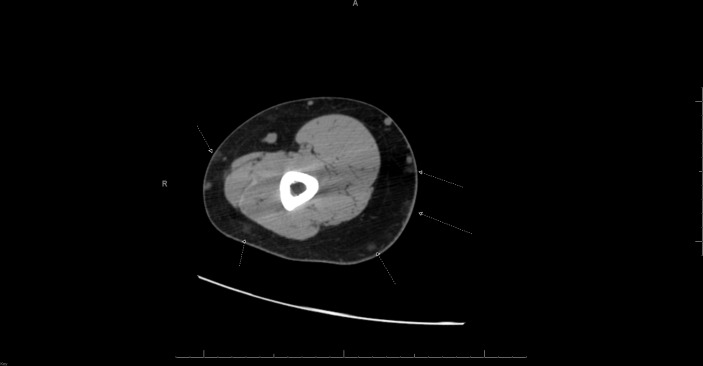

Previous investigation by CT scan of the upper extremity reported ‘innumerable small subcutaneous lesions throughout both arms, many of which contain fat with other several small lesions having soft tissue appearance’ (figure 1). About 4 years prior to presentation, he had a surgical excision of three masses in his right arm and two masses of his left arm. A pathology report of the specimen from the right forearm described a yellow, fatty thinly encapsulated piece of tissue, and a final diagnosis of angiolipoma was described.

Figure 1.

Innumerable small subcutaneous lesions throughout both arms, many of which contain fat with other several small lesions having soft tissue appearance. The lipomatous lesions and small soft tissue nodules are indeterminate. Arrows point to innumerable small subcutaneous lesions through both arms.

On review of his laboratory testing, notable findings included a borderline elevation of his inflammatory markers, including a C reactive protein of 1.04 mg/dL (reference range: <1.00 mg/dL) and sedimentation rate of 16 mm/hour (reference range of 0 to 15 mm/hour). An antinuclear antibody screen and rheumatoid factor were negative. Testing of complement activity with C3 and C4 levels were within normal limits. A thyroid-stimulating hormone test and total T4 was unremarkable. His creatinine phosphokinase was within normal limits at 93 IU/L (reference range: 30 to 223 IU/L). A serum immunofixation study reported a normal pattern with no monoclonal proteins seen.

Differential diagnosis

Adiposis dolorosa is a proliferation of painful subcutaneous nodules. Diagnostic criteria have yet to be elucidated and is often only definitively made histopathology. A list of conditions that need to be excluded include fibromyalgia, Cushing syndrome, multiple symmetric lipomatosis, familial multiple lipomatosis and lipoedema.

Fibromyalgia is a disease characterised by widespread musculoskeletal pain in addition to psychiatric symptoms, cognitive disturbances and fatigue.3 Though the diseases may present similarly, the pain of adiposis dolorosa is specifically associated with fatty nodules though this distinction may be distorted by obesity.4 In addition, the pain pattern in adiposis dolorosa has been described to be more focal, while fibromyalgia is more generalised, worsened after exercise and is often associated with sleep disturbances not seen in adiposis dolorosa.5 Even the correct diagnosis of adiposis dolorosa does not exclude the possibility of concomitant fibromyalgia, since fibromyalgia also affects many patients diagnosed with other chronic inflammatory and rheumatological syndromes.

Cushing syndrome is a disorder of excess cortisol characterised by proximal muscle weakness, increased fat deposition (face, back, abdomen) and lethargy. A number of neuropsychiatric symptoms may also be seen including depression and memory loss.6 Typically, the pain or discomfort of Cushing syndrome is not associated with nodular deposits of fat. A 24-hour urinary free cortisol excretion or a dexamethasone suppression test should distinguish the two, as cortisol excess is seen in Cushing and should not be seen in adiposis dolorosa.7

Multiple symmetric lipomatosis (MSL) is a rare disorder of abnormal lipid metabolism characterised deposition of large symmetric lipomatous masses on the neck shoulders, arms and trunk. The disease is seen with a male to female ratio of 15:1 to 30:1 and is commonly seen with a history of alcoholism. MSL is seen both with sporadic and autosomal-dominant inheritance.8 Notably, the fatty deposition of MSL is not associated with pain and is familial, so it can usually be differentiated from adiposis dolorosa.1

Familial multiple lipomatosis (FML) is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterised by asymmetric deposition of fat that is clinically distinct from multiple symmetric lipomatosis. The hallmark of FML is multiple widespread painless lipomas that predominate in the extremities with sparing of the head and shoulders.9 10 Absence of pain and the hereditary nature of FML should distinguish it from adiposis dolorosa.

Lipoedema is disease of lipid metabolism characterised by symmetric lower extremity swelling due to abnormal deposition of fatty deposits. Interestingly, the disease is seen nearly exclusively in women and may have a hereditary basis. On palpation, the lower extremities will be tender and the disease course is typically gradually progressive.11

Several more serious systemic conditions should also be considered. A high clinical index of suspicion needs to be maintained for possible cutaneous malignant metastasis. The clinical presentation is often subtle and a recent study has supported the use of dermoscopy as a helpful tool in diagnosis, especially in patients with a history of known cancer. Some helpful clinical presentations reportedly include, in order of frequency, multiple or single nodules, plaques and ulcers. The aforementioned case series noted a high prevalence of vascular on dermoscopy with the most common pattern being serpentine vessels.12 Absence of pain favours the diagnosis of cutaneous malignant metastases, as these are typically not painful.1

Cutaneous involvement of sarcoidosis is an additional consideration in the workup of subcutaneous nodules. Its manifestations vary significantly in terms of morphology and, as such, it is often referred to as a ‘great imitator’. Common clinical signs include papules, plaques or lupus pernio. Ultimately, diagnosis is contingent on both compatible clinical evidence in conjunction with histology suggesting non-caseating granulomas.13 To complicate matters, the distinction between sarcoidosis and sarcoid-like reactions is increasingly debated, with recent diagnostic criteria proposed but not yet clinically implemented.14 Differentiation currently requires a combination of diagnostic testing to exclude or prove infectious, tumorous or immunogenic antigens in addition to a genetic profile of the patient.15 Absence of pulmonary symptoms and a normal chest X-ray make this highly unlikely here.

Finally, cutaneous tuberculosis may need to be entertained in the appropriate setting. Cutaneous involvement has been posited to be secondary exogenous inoculation, continuous spread or haematogenous dissemination. Systemic symptoms, including fever, chills, weight loss and cough with haemoptysis should point towards this diagnosis. Diagnosis is made more easily by sputum culture, but skin biopsy with PCR can also make the diagnosis.16

Treatment

Prior to our consultation, the patient had undergone surgical excision of a total of five masses in his forearms and had trials of a wide range of analgesic medications including narcotics, benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, antidepressants and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Multiple additional promising investigational therapies have been reported including treatment with transcutaneous frequency rhythmic electrical modulation system (FREMS). A case report observed marked improvement in functional and health status in addition to reduced pain and improvement in subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness and fat compactness with FREMS electrotherapy.17

Outcome and follow-up

On presentation, patient was being treated with multiple classes of pain medications including narcotics (morphine ER; oxycodone-acetaminophen), benzodiazepines (clonazepam), muscle relaxants (baclofen; tizanidine), antidepressants (amitriptyline) and NSAIDs (ibuprofen). Following our consultation, he has been instructed to taper off the clonazepam with plans to transition to tapentadol as a replacement for morphine ER and oxycodone-acetaminophen pending a sleep study.

Discussion

Adiposis dolorosa is a disease of unknown prevalence and is listed by the National Organization of Rare Disorders.18 A clinical hallmark of adiposis dolorosa is the accumulation of subcutaneous nodules or lipomas. Associated symptoms commonly seen may include weakness, fatigue, depression, bruising and anxiety.19 A proposal in 1901 by Roux and Vitaut proposed four cardinal symptoms including multiple painful fatty masses, generalised obesity, weakness and susceptibility to fatigue and psychiatric manifestations.20 Recent recommendations put forth describe fewer diagnostic criteria, including obesity and chronic pain (>3 months) in the adipose tissue.1

The aetiology of adiposis dolorosa is unknown, though multiple theories have been purported, including inflammation, adipose tissue dysfunction and trauma.1 On histopathology, the fat deposition in adiposis dolorosa is notable for mature adult fatty tissue and sometimes, a number of blood vessels suggesting angiolipoma. Adiposis dolorosa has not been associated with malignancy.4

Learning points.

Adiposis dolorosa is a rare disease characterised by painful adipose tissue with multiple associated symptoms.

A high index of suspicion is necessary as the presentation commonly overlaps with other diagnoses.

Prompt recognition and validation of adiposis dolorosa as a source of legitimate pain may help guide next therapeutic steps.

Footnotes

Contributors: DH, NU and AAD contributed equally to writing the manuscript. DH conducted the literature search. AO was primarily involved in patient care. All the authors have given final approval for the version to be submitted.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Review of Dercum’s disease and proposal of diagnostic criteria, diagnostic methods, classification and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012;7:23 10.1186/1750-1172-7-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dercum FX. A subcutaneous connective tissue dystrophy of the arms and back, associated with symptoms resembling myxoedema. J Nerv Ment Dis 1888;13:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bennett RM. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2009;35:215–32. 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wortham NC, Tomlinson IP. Dercum’s disease. Skinmed 2005;4:157–62. 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2005.03675.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McGevna LF. Adiposis dolorosa. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1082083-overview

- 6. Nieman LK. Cushing’s syndrome: update on signs, symptoms and biochemical screening. Eur J Endocrinol 2015;173:M33–M38. 10.1530/EJE-15-0464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al. . The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:1526–40. 10.1210/jc.2008-0125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jang JH, Lee A, Han SA, et al. . Multiple symmetric lipomatosis (Madelung’s disease) presenting as bilateral huge gynecomastia. J Breast Cancer 2014;17:397–400. 10.4048/jbc.2014.17.4.397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gologorsky Y, Gologorsky D, Yarygina AS, et al. . Familial multiple lipomatosis: report of a new family. Cutis 2007;79:227–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tana C, Tchernev G. Familial multiple lipomatosis. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2014;371:1237 10.1056/NEJMicm1316241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shin BW, Sim YJ, Jeong HJ, et al. . Lipedema, a rare disease. Ann Rehabil Med 2011;35:922–7. 10.5535/arm.2011.35.6.922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chernoff KA, Marghoob AA, Lacouture ME, et al. . Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol 2014;150:429–33. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Katta R. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: a dermatologic masquerader. Am Fam Physician 2002;65:1581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chokoeva AA, Tchernev G, Tana M, et al. . Exclusion criteria for sarcoidosis: a novel approach for an ancient disease? Eur J Intern Med 2014;25:e120 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tchernev G, Tana C, Schiavone C, et al. . Sarcoidosis vs. sarcoid-like reactions: the two sides of the same coin? Wien Med Wochenschr 2014;164:247–59. 10.1007/s10354-014-0269-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hill MK, Sanders CV. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr 2017;5 10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0010-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martinenghi S, Caretto A, Losio C, et al. . Successful treatment of Dercum’s disease by transcutaneous electrical stimulation: a case report. Medicine 2015;94:e950 10.1097/MD.0000000000000950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dercum’s Disease. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/dercums-disease/

- 19. Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A. Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;56:901–16. 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roux J, Vitaut M. Maladie de dercum (adiposis dolorosa). Revue Neurol 1901;9:881–8. [Google Scholar]