Abstract

A 77-year-old Caucasian woman with recent abdominal surgery was diagnosed with multiple paradoxical systemic emboli in the mesenteric and renal circulation. Diagnosis was made by direct visualisation of a serpentine thrombus traversing both atria through patent foramen ovale (PFO) by transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE). Concomitantly, the patient was found to have deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A decision was made to pursue cardiothoracic surgery preceded by inferior vena cava filter placement. She was started on intravenous anticoagulation. Repeat TEE was negative for thrombus and the patient did not present any new clinical signs of embolisation by this time. Consequently, the treatment plan was modified and the patient received oral systemic anticoagulation followed by PFO closure with the use of St. Jude Amplatzer Cribriform septal occluder device. During the outpatient follow-up the patient was asymptomatic and there was no significant flow through the device on transthoracic echocardiogram.

Keywords: interventional cardiology, cardiovascular medicine

Background

Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is a common finding on echocardiography. Prevalence is estimated as 25% in general population.1 In majority of cases, this is an incidental finding without clinical significance. Nevertheless, in certain situations this condition can be associated with a phenomenon of paradoxical embolisation. While the proposed mechanism of paradoxical embolisation as a consequence of thrombus migration from venous to systemic circulation via communication in between the atria is generally accepted, causative relationship of these two findings is difficult to be proven.

This is a case of a 77-year-old woman diagnosed with multiple paradoxical systemic embolisation in the mesenteric and renal circulation. Diagnosis was made by direct visualisation of a serpentine thrombus traversing both atria through the PFO in the context of concomitant deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). This is a rarely documented finding with high risk of complications, predominantly reported in the setting of simultaneous PE.2–8

Case presentation

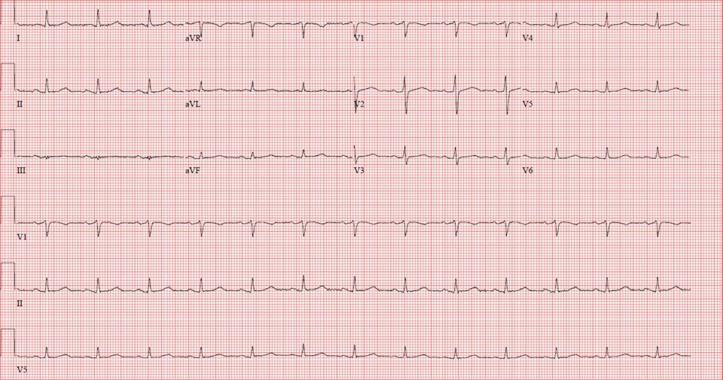

A 77-year-old Caucasian woman presented with progressively worsening abdominal and chest pain. Physical examination was pertinent for lower extremity oedema, a diffusely tender abdomen and absence of cardiac murmur. The ECG showed normal sinus rhythm (figure 1). She was found to have small-bowel obstruction on X-ray. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) obtained during pre-surgical clearance revealed an ejection fraction of 60%–65%, mild-to-moderate pulmonary hypertension and a cylindrical mass in the left atrium suspicious for a thrombus or tumour. She was taken to the operating room where a 10 cm ischaemic appearing terminal ileum was removed.

Figure 1.

ECG with normal sinus rhythm.

Investigations

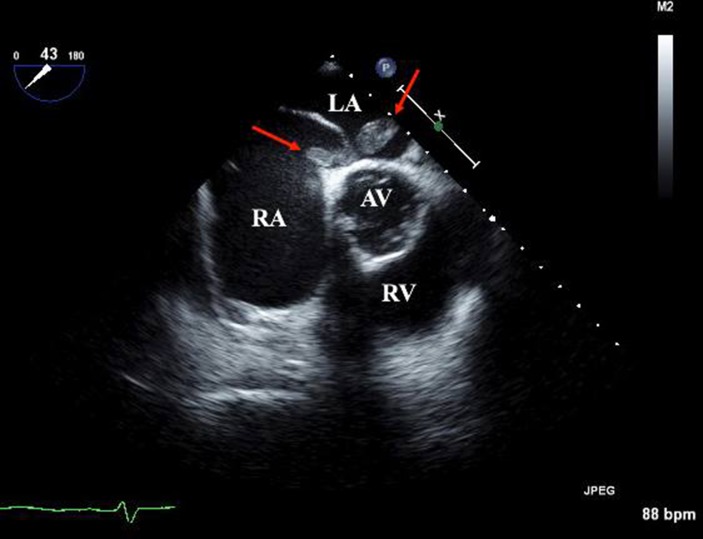

Cardiology was consulted for further evaluation of interatrial finding. Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) revealed a large 6 cm × 1 cm serpentine thrombus in both the left and right atrium traversing through the PFO (figure 2, video 1). CT revealed filling defects in the right basilar pulmonary vessels, non-occlusive thrombi in the super mesenteric artery and numerous renal infarcts. Ultrasound scan of the lower extremities revealed acute thrombi in the left femoral, popliteal and posterior tibial veins. Cardiac monitoring did not register any episodes of atrial fibrillation during the admission.

Figure 2.

TEE mid-oesophageal AV short-axis. Red arrows pointing thrombus traversing both atria via interatrial communication. AV, aortic valve; LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; TEE, transesophageal echocardiogram.

Video 1.

Transesophageal echocardiogram mid-oesophageal aortic valve long-axis revealing longitudinal 6 cm thrombus in left.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of the initial finding on TTE included thrombus or intracardiac mass, which could represent either primary tumour, most commonly myxoma, or metastatic lesion. Peripheral embolisation visualised on CT likely represented paradoxical embolisation through the PFO, but could also be the consequence of atrial fibrillation.

Treatment

Post TEE she was started on a heparin drip. Cardiothoracic surgery was consulted for possible thrombus intervention and closure of the PFO. A decision was made to place an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter and perform repeat TEE before the possible cardiothoracic procedure. The IVC filter was placed without complications. Repeat TEE revealed a tunnel-like PFO without thrombus. By this time, no new clinical signs of peripheral embolisation were observed. In this context, cardiothoracic surgery was cancelled and the patient remained on systemic anticoagulation with resolution of chest pain, followed by successful transcutaneous PFO closure with a 35 mm St. Jude Amplatzer Cribriform septal occluder device (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN) after few weeks. As the episode of DVT was classified as non-provoked, the patient qualified for life-long anticoagulation.

Outcome and follow-up

During postprocedural cardiology outpatient follow-up visit, the patient remained asymptomatic from cardiac standpoint and did not present any signs of repetitive systemic embolisation. TTE showed no significant flow across the device.

Discussion

PFO is an embryological remnant of physiological connection in between the left and right atrium in fetal circulation. In majority of cases, the foramen ovale closes within the first 2 weeks postnatally. In 20%–25% of cases though, the foramen ovale persists.1 The gold standard of diagnosis includes TEE with agitated saline contrast. Sensitivity can be additionally enhanced by performing a Valsalva manoeuvre during the procedure.9 Contrast-enhanced transcranial Doppler is an innovatory, low-cost, non-invasive diagnostic alternative.10 It is important to distinguish PFO from atrial septal defect (ASD), which is a structural lesion, resulting from developmental failure of the septum primum or secundum in heart embryogenesis starting in the fifth week of gestation.11 PFO though may coexist with any anatomical defect including ASD or septum aneurysm. Usually in asymptomatic patients, PFO is an incidental finding without any clinical implication. Nevertheless, PFO is associated with certain medical conditions including paradoxical embolisation, migraine, especially with aura, caisson disease and orthodeoxia syndrome.12

The epidemiology of paradoxical embolisation is not established yet. It has been proposed that increased risk for paradoxical embolisation may be associated with the PFO size and the presence of atrial septal aneurysm, prominent Eustachian valve, Chiari network and hypercoagulability.13 Apart from Valsalva manoeuvre, PFO-related events may be provoked by other situations enhancing shunting by increase in right atrial pressure, including mechanical ventilation,14 diving,15 pulmonary embolisation16 or a right-sided cardiac tumour.17 It is implied in the literature that <1% of myocardial infarctions are caused by paradoxical embolism via an interatrial communication.18

The most important from a clinical perspective is the association between PFO and cryptogenic stroke. Consequently, the beneficence of PFO closure as secondary stroke prevention is being intensively investigated.19 20 Large PFO closure studies included CLOSURE I, PC-Trial, RESPECT and the most recent CLOSE and REDUCE trials.21–25 All trials are directed towards superiority of PFO closure versus medical therapy alone, nevertheless neither CLOSURE nor PC-Trial achieved the level of statistical significance. Long-term follow-up of RESPECT trial was the first study showing the advantage of PFO closure for secondary prophylaxis of cryptogenic stroke. As a result, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in October 2016 approved the use of Amplatzer PFO occluder in patients between 18 and 60 years old with cryptogenic stroke. More recently, CLOSE and REDUCE trials also revealed the superiority of PFO closure over medical treatment.

Current guidelines of the American Heart Association and American Academy of Neurology recommend against routine PFO closure in cryptogenic stroke. There are certain special circumstances where percutaneous closure of the PFO may be offered, including recurrent stroke of unknown mechanism despite adequate antiplatelet therapy and PFO with concomitant DVT with high risk of reoccurrence.26 27

The finding of trapped thrombi in the PFO as presented in our case adequately supports its causative role in the pathogenesis of systemic embolisation. Potential risk factors for the patient for PFO-related complications included hypercoagulability complicated with DVT and PE. Additionally, the patient’s clinical situation was problematical due to intestinal ischaemia requiring emergent surgery, which furthermore increased the patient’s risk for paradoxical embolisation in the light of temporal need for mechanical ventilation. As trapped-in PFO thrombus is a rare finding, no standardised treatment has been established yet. There are reported cases of successful treatment with both conservative and surgical approach.2–8 It was implied though that surgical approach is associated with a lower overall incidence of post-treatment embolic events and a lower 60-day mortality compared with systemic thrombolysis or anticoagulation.16 Prophylactic PFO closure should also be considered in the presence of hypercoagulable state.28 Surgical approach was our initial plan, which was modified in the view of subsequent negative TEE findings for thrombus. Fortunately, the patient did not develop any new signs of ischaemia at that time and further treatment with systemic anticoagulation followed by percutaneous PFO closure appeared to be successful.

In conclusion, the above case presents a rarely documented phenomenon of trapped thrombi in PFO with finding of multiple paradoxical emboli. This is an exceptional occurrence, beyond current guidelines, where prompt treatment should be applied to prevent further complications, including stroke.

Learning points.

Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is a potential, but rare cause of systemic embolisation.

Thrombus trapped in PFO is an uncommon finding requiring prompt treatment.

Current American Heart Association and American Academy of Neurology guidelines recommend against routine PFO closure for secondary stroke prevention.

Footnotes

Contributors: DMZ and YA were resident physicians admitting and following up the patient during the hospitalisation. JKK was the attending cardiologist performing TEE and following up the patient during the admission and in outpatient cardiology clinic.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hara H, Virmani R, Ladich E, et al. Patent foramen ovale: current pathology, pathophysiology, and clinical status. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:46 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mascarenhas V, Kalyanasundaram A, Nassef LA, et al. Simultaneous massive pulmonary embolism and impending paradoxical embolism through a patent foramen ovale. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1338 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rinaldi JP, Latcu DG, Saoudi N. Real-time 3-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography for the diagnosis of a thrombus straddling the patent foramen ovale. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:e7 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koullias GJ, et al. Massive paradoxical embolism: caught in the act. Circulation 2004;109:3056–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000132371.91318.6D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramani GV, Kligerman S, Lehr E. Multimodality imaging of thrombus in transit crossing a patent foramen ovale. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:e19 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukumoto A, et al. Continuous thrombus in the right and left atria penetrating the patent foramen ovalis. Circulation 2005;112:e143–e144. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.489906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdelsalam M, Mumtaz M, Sackman I. Thrombus in transit through a patent foramen ovale. Heart 2012;98:1184 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-301659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sattar A, Win TT, Schevchuck A, et al. Extensive biatrial thrombus straddling the patent foramen ovale and traversing into the left and right ventricle. BMJ Case Rep 2016;2016:bcr2016216761 10.1136/bcr-2016-216761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinto FJ. When and how to diagnose patent foramen ovale. Heart 2005;91:438–40. 10.1136/hrt.2004.052233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blersch WK, Draganski BM, Holmer SR, et al. Transcranial duplex sonography in the detection of patent foramen ovale. Radiology 2002;225:693–699. 10.1148/radiol.2253011572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore KL. The developing human: clinically oriented embryology. 6th ed Philadelphia: Saunders, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kutty S, Sengupta P, Khandheria B, et al. The Known and the To Be Known. Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:1665–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun YP, Homma S, Ovale PF. and Stroke. Circ J 2016;80:1665–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cujec B, Polasek P, Mayers I, et al. Positive end-expiratory pressure increases the right-to-left shunt in mechanically ventilated patients with patent foramen ovale. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:887–94. 10.7326/0003-4819-119-9-199311010-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boussuges A, Blanc F, Carturan D. Hemodynamic changes induced by recreational scuba diving. Chest 2006;129:1337–43. 10.1378/chest.129.5.1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seo WW, Kim SE, Park MS, et al. Systematic review of treatment for trapped thrombus in patent foramen ovale. Korean Circ J 2017;47:776–85. 10.4070/kcj.2016.0295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diaz Castro O, Bueno H, Nebreda LA. Acute myocardial infarction caused by paradoxical tumorous embolism as a manifestation of hepatocarcinoma. Heart 2004;90:e29 10.1136/hrt.2004.033480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleber FX, Hauschild T, Schulz A, et al. Epidemiology of myocardial infarction caused by presumed paradoxical embolism via a patent foramen ovale. Circ J 2017;81:1484–9. 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-0995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L, Luo S, Yan L, et al. A systematic review of closure versus medical therapy for preventing recurrent stroke in patients with patent foramen ovale and cryptogenic stroke or transient ischemic attack. J Neurol Sci 2014:337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kent DM, Dahabreh IJ, Ruthazer R, et al. Device closure of patent foramen ovale after stroke: pooled analysis of completed randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:907–17. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elmariah S, Furlan AJ, Reisman M, et al. Predictors of recurrent events in patients with cryptogenic stroke and patent foramen ovale within the closure i (evaluation of the starflex septal closure system in patients with a stroke and/or transient ischemic attack due to presumed paradoxical embolism through a patent foramen ovale) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2014;7:913–20. 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.01.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meier B, Kalesan B, Mattle HP, et al. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic embolism. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2013;368:1083–91. 10.1056/NEJMoa1211716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saver JL, Carroll JD, Thaler DE, et al. Long-term outcomes of patent foramen ovale closure or medical therapy after stroke. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1022–32. 10.1056/NEJMoa1610057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mas JL, Derumeaux G, Guillon B, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure or anticoagulation vs. antiplatelets after stroke. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1011–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1705915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sondergaard L, Kasner SE, Rhodes JF, et al. Gore REDUCE clinical study investigators. patent foramen ovale closure or antiplatelet therapy for cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1033–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke 2014;45:2160–236. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Messé SR, Gronseth G, Kent DM, et al. Practice advisory: recurrent stroke with patent foramen ovale (update of practice parameter): report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the american academy of neurology. Neurology 2016;87:815 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chow V, Wang W, Wilson M, et al. Thrombus in transit within a patent foramen ovale: an argument for consideration of prophylactic closure? J Clin Ultrasound 2012;40:115–8. 10.1002/jcu.20820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]