Abstract

A 45-year-old woman was diagnosed as having multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A in 2014. She had bilateral pheochromocytoma, medullary thyroid carcinoma and biopsy-proven cutaneous lichen amyloidosis in the interscapular area. She underwent bilateral adrenalectomy; following which, she achieved clinical and biochemical remission. She was planned for total thyroidectomy at a later date; however, she was lost to follow-up. She presented to us again in December 2016 with abdominal pain. Examination revealed hypertension with postural drop. Positron emission tomography scan showed Ga68 and fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid suprarenal, hepatic, peritoneal and mesenteric masses with abdominal lymph nodes. Twenty-four-hour urinary metanephrines/normetanephrines were elevated. Serum calcitonin was as high as it was 2-1/2 years ago. Ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) from the liver mass revealed neuroendocrine cells that did not stain for calcitonin. Hence, a diagnosis of metastatic pheochromocytoma was made. She underwent total thyroidectomy and was started on cyclophosphamide, vincristine, dacarbazine-based chemotherapy regimen.

Keywords: adrenal disorders, thyroid disease, endocrine cancer

Background

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A (MEN 2A) is an autosomal-dominant syndrome characterised by the presence of two or more specific endocrine tumours in a single individual, namely medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC), pheochromocytoma and/or parathyroid adenoma/hyperplasia. MTC affects over 95% of individuals with MEN 2A and tends to be bilateral and multifocal. Moreover, cervical lymph node involvement is demonstrable in about 40%–50% of such patients at diagnosis, making cure difficult. Pheochromocytoma, on the other hand, occurs in only 50% of patients with MEN 2A. In most cases, they involve both the adrenals, although metachronous development is common. Unlike MTC, pheochromocytomas in MEN 2A are usually benign, with malignancy being reported in only 3%–4% of cases.1 2 Herein, we report a case of a 45-year-old woman who was diagnosed as having MEN 2A 2 years back and had undergone laparoscopic bilateral adrenalectomy. Now she presented to us with abdominal pain and on evaluation was found to have bilateral suprarenal, peritoneal and intrahepatic masses; fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology with immunohistochemistry was suggestive of pheochromocytoma. She was started on cyclophosphamide/vincristine/dacarbazine (CVD)-based chemotherapy regimen.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old woman presented to our institute in March 2014 with the history of a pruritic rash over her upper back that had been bothering her for the last 4 years. This was associated with paroxysms of headache, sweating and palpitations over the past 3 years and giddiness on standing for the last year. On examination, she had hypertension with significant postural drop of blood pressure. There was a hyperpigmented, scaly skin rash over the interscapular area. She had grade I hypertensive retinopathy. Investigations revealed elevated 24-hour urinary vanillylmandelic acid (49 mg/day, range 0.0–13.6 mg/day), elevated plasma-free metanephrine (404 pg/mL, range <90 pg/mL) and raised serum calcitonin level (377 pg/mL, range <0.0–11.5 pg/mL). Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen revealed bilateral hypervascular suprarenal lesions with a solid-cystic appearance (right measuring 3.4×3.6×4.1 cm and left measuring 3.8×3.1×3.5 cm), suggestive of bilateral pheochromocytoma. Ga68-DOTATATE scintigraphy revealed somatostatin receptor expression in them. Ultrasonography (USG) of the neck showed multifocal heterogeneous hypoechoic nodules in both the lobes of the thyroid gland with central amorphous calcifications; however, there was no cervical lymphadenopathy. Fine-needle aspirate from the largest nodule was suggestive of MTC. Skin biopsy from the interscapular area revealed cutaneous lichen amyloidosis (CLA). In view of MTC, bilateral pheochromocytomas and CLA, a clinical diagnosis of MEN 2A was made. Genetic analysis revealed a mutation in codon 634 at exon 11 of the RET proto-oncogene (cysteine-to-arginine substitution, C634R). She was started on α-blockers, followed by β-blockers and underwent laparoscopic bilateral adrenalectomy in April 2014. The perioperative period was uneventful. Histopathology was suggestive of bilateral pheochromocytoma with a Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score of 8. Postoperatively, she became normotensive and plasma-free metanephrine repeated 2 weeks after surgery had normalised (14 pg/mL). She was discharged on oral hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone replacement and was advised to follow up after 3 months for total thyroidectomy. However, she was lost to follow-up.

She presented to us 2-1/2 years later in December 2016 with diffuse abdominal pain which she had been experiencing for the past 3 months. She had hypertension and postural drop on examination. There were no clinically palpable lumps in the abdomen or in the neck.

Investigations

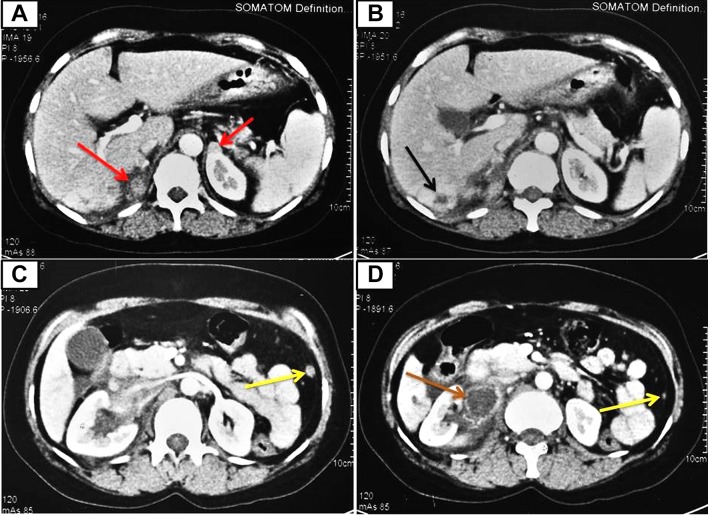

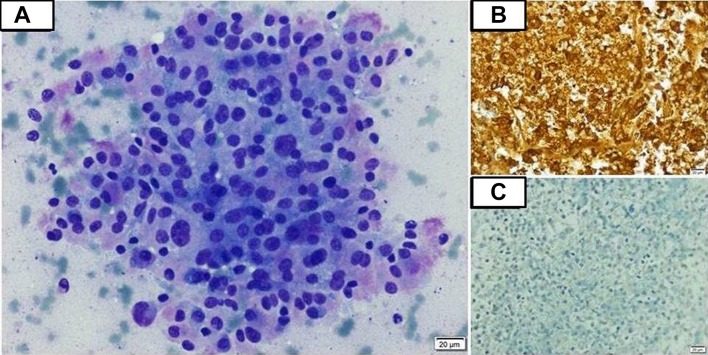

Complete blood count revealed haemoglobin 10.3 g/dL, total leukocyte count (TLC) 5.2×109/L and platelet count 362×109/L. Renal and liver function tests were normal. Her corrected serum calcium was 9.5 mg/dL. Twenty-four-hour urinary metanephrine (2662.5 µg/day, range <350 µg/day) and normetanephrine (10 998.75 µg/day, range <600 µg/day) were highly elevated. Serum calcitonin level was high (403 pg/mL, range 0.0–11.5 pg/mL). Serum carcinoembryonic antigen level was normal (2.1 ng/mL, range 0.0–5.0 ng/mL). USG of the abdomen revealed bilateral suprarenal masses along with a space occupying lesion in segment VI of the liver. USG of the neck showed hypodense lesions in bilateral thyroid lobes with no cervical lymphadenopathy (as was present in 2014). Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen (figure 1) revealed bilateral enhancing suprarenal lesions (marked in red arrows), hypodense lesion in segment VI of the liver (marked in black arrow), multiple enhancing peritoneal deposits (marked in yellow arrows) and a peripherally enhancing, centrally necrotic coalescing lymph node mass in the right renal hilar region (marked in brown arrow). Whole-body positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scan revealed Ga68 and FDG-avid bilateral suprarenal lesions (right measuring 2.2×3.0 cm, left measuring 1.2×1.0 cm), a hypodense lesion in the liver (measuring 2.7×2.5 cm), multiple lesions in the perirenal, perisplenic, peripancreatic locations and diffuse peritoneal and omental deposits. In addition, there were mild tracer avid hypodense lesions in both lobes of the thyroid with no cervical lymph node involvement. FNA was performed under USG guidance from the hepatic space-occupying lesion. Cytological examination showed moderately pleomorphic tumour cells with round-to-oval nuclei, coarse chromatin, moderate-to-abundant cytoplasm with fine pink granules (figure 2A). Immunocytochemistry revealed neuron-specific enolase and chromogranin positivity (figure 2B) indicating neuroendocrine origin of the tumour cells; however, they were negative for calcitonin (figure 2C) and inhibin, ruling out MTC and adrenocortical carcinoma, respectively.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen showing heterogeneously enhancing bilateral suprarenal lesions (marked in red arrows), a hypodense lesion in segment VI of the liver (marked in black arrow), multiple enhancing nodular peritoneal deposits (marked in yellow arrows) and a peripherally enhancing, centrally necrotic coalescing lymph node mass in the right renal hilar region (marked in brown arrow).

Figure 2.

(A) Photomicrograph of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) smear showing moderately pleomorphic tumour cells with round-to-oval nuclei, coarse chromatin and moderate-to-abundant amount of cytoplasm with fine pink granules (May-Grunwald Giemsa; 200x). (B) Photomicrograph of FNA smear showing strongly positive chromogranin staining by the tumour cells suggestive of a neuroendocrine tumour (100x). (C) Photomicrograph of FNA smear showing absence of calcitonin staining by the tumour cells, thus ruling out medullary thyroid carcinoma (100x).

Differential diagnosis

When a patient of MEN 2A presents with distant metastasis, the diagnosis is rather straightforward: metastatic MTC. This seemed the likely possibility in our patient, too, as she had been harbouring the MTC for more than 2 years. However, there were two odd points. First, cervical lymph nodes were not involved, neither clinically nor on imaging. Distant metastasis in the absence of cervical lymph node spread is rare in MTC.3 Second, her serum calcitonin level at this admission was 403.0 pg/mL. Serum basal calcitonin levels above 500 pg/mL indicate high risk of local or distant metastasis.4 In addition, rising calcitonin levels correlate with disease activity and calcitonin doubling time of less than 25 months tend to predict tumour progression.5 However, her calcitonin level was almost the same even after 2-1/2 years. These factors pointed against metastatic MTC and we had to get an FNA done from the liver lesion to clinch the diagnosis.

Treatment

Patient’s blood pressure was adequately controlled with α-blockade followed by β-blockade. She underwent total thyroidectomy with prophylactic central lymph node dissection in February 2017. Histopathological examination of the excised tissue was suggestive of multifocal MTC, being positive for calcitonin on immunohistochemistry. The resection margins and the excised lymph nodes were free of tumour. She was started on oral levothyroxine supplementation. Serum calcitonin level was repeated 2 weeks after surgery which came out to be undetectable, further supporting our diagnosis of metastatic pheochromocytoma rather than metastatic MTC. Lutetium177-based therapy was planned; however, in view of extensive metastasis, it could not be done. Hence, she was started on CVD-based chemotherapy regimen (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, dacarbazine) after informed consent.

Outcome and follow-up

To date, she has received six cycles of CVD-based chemotherapy at an interval of every 21 days. Post three cycles of chemotherapy, her antihypertensive requirement diminished and we were able to stop α-blockers and β-blockers altogether after the fourth cycle. She has been tolerating the chemotherapy well; however, after the fourth cycle, she developed febrile neutropaenia which was successfully managed with broad-spectrum antibiotics and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor) injections. Whole-body PET-CT done at the completion of six cycles of chemotherapy showed progressive disease as per Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumours (RECIST); however, metabolic uptake of 18FDG by the existing metastatic lesions decreased significantly. Biochemical evaluation after six cycles revealed 24-hour urinary metanephrine of 1702.4 µg/day and normetanephrine of 2042.88 µg/day, a drastic reduction from the prechemotherapy values. She is completely asymptomatic and is presently having an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 1. She is planned for cisplatin-based second-line chemotherapy.

Discussion

Pheochromocytoma is found in about 50% of patients with MEN 2A. Pheochromocytomas in MEN 2A are usually adrenal in location, benign and bilateral, although they may be metachronous in origin. In most cases, MTC tends to predate the occurrence of pheochromocytomas; however, they may be synchronous in 34% of patients.6 Malignant pheochromocytoma in MEN 2A is a rare entity. Most of the largest case series of MEN 2A reported in the world literature to date do not mention about metastatic pheochromocytoma.6–8 Occasional case series have, however, reported an incidence of 3%–4%.1 2 These are supported by a handful number of anecdotal case reports.9–15 This contrasts against sporadic pheochromocytoma where the incidence of malignancy can be as high as 10%.

Considering its rarity, making a diagnosis of metastatic pheochromocytoma in our patient was not a piece of cake. Distant metastasis is a well-known entity in MTC; hence, metastatic MTC was high on the cards. However, as has already been mentioned, the absence of cervical lymph node involvement and the ‘relatively stationary’ calcitonin levels were the soft pointers against a diagnosis of metastatic MTC. On the contrary, the resurgence of hypertension and the sky high urinary metanephrine and normetanephrine levels were hinting towards metastatic pheochromocytoma. Whole-body FDG and Ga68-DOTATATE PET-CT were not of much help either in differentiating between the two entities, as FDG and Ga68 avidity have both been described in metastatic MTC and pheochromocytoma. Finally, FNA from the liver lesion clinched the diagnosis. It showed that tumour cells that were positive for neuroendocrine markers (that could be seen in both MTC and pheochromocytoma), however, were negative for calcitonin, thereby ruling out MTC. Moreover, post total thyroidectomy, her serum calcitonin levels became undetectable, thereby confirming the diagnosis of metastatic pheochromocytoma.

Treating metastatic pheochromocytoma has always been challenging and, mostly, disappointing. Combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, vincristine and dacarbazine remains the first-line therapy. Averbuch et al had reported a complete and partial (radiological) response of 57% following a median duration of therapy of 21 months. Biochemical response was noted in 79% of patients with objective improvement in blood pressure in all the responding patients.16 On the contrary, Deutschbein et al treated eight patients of malignant pheochromocytoma with CVD regimen and after a median of six cycles of chemotherapy, none could achieve complete remission while only two patients achieved partial remission. The median progression-free survival was 5.4 months.17 In another study, Huang et al reported a complete response rate of 11% and a partial response rate of 44%. However, over 22 years of follow-up, there was no difference in the overall survival among patients whose tumours objectively shrank in size versus those with stable or progressive disease.18 Moreover, patients who have already been treated with chemotherapy but demonstrate new progressive lesions on follow-up, subsequent courses may result in relevant disease stabilisation and prolong progression-free survival.17 Second-line chemotherapy regimens include anthracycline plus CVD or etoposide plus a platinum-based drug. In addition, the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib offers a ray of hope for patients who have failed on both first-line and second-line chemotherapy regimens. Our patient did show clinical improvement on chemotherapy in the form of amelioration of hypertension and preservation of general well-being; however, PET-CT at the end of six cycles of chemotherapy showed evidence of progressive disease as per RECIST19 in spite of the fact that there was a significant reduction in the metabolic uptake of 18FDG by the existing tumorous lesions. The discrepancy between clinical and radiological response highlights the fact that RECIST alone might not be sufficient for assessment of treatment response in neuroendocrine tumours like malignant pheochromocytomas.20

Learning points.

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A (MEN 2A) is usually metastatic; however, distant metastasis in the absence of cervical lymph node involvement is rare.

Rising serum calcitonin levels and a short calcitonin doubling time predicts MTC progression.

Metastatic pheochromocytoma, although rare, can occur in patients with MEN 2A.

Footnotes

Contributors: RP prepared the manuscript. AR helped in the management of the patient. SK had been the operating surgeon. AB conceptualised the manuscript and provided overall guidance.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Casanova S, Rosenberg-Bourgin M, Farkas D, et al. Phaeochromocytoma in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 A: survey of 100 cases. Clin Endocrinol 1993;38:531–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1993.tb00350.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Modigliani E, Vasen HM, Raue K, et al. Pheochromocytoma in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2: European study. The Euromen Study Group. J Intern Med 1995;238:363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Machens A, Holzhausen H-J, Lautenschläger C, et al. Enhancement of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis of thyroid carcinoma: A multivariate analysis of clinical risk factors . Cancer 2003;98:712–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Machens A, Dralle H. Biomarker-based risk stratification for previously untreated medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:2655–63. 10.1210/jc.2009-2368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laure Giraudet A, Al Ghulzan A, Aupérin A, et al. Progression of medullary thyroid carcinoma: assessment with calcitonin and carcinoembryonic antigen doubling times. Eur J Endocrinol 2008;158:239–46. 10.1530/EJE-07-0667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thosani S, Ayala-Ramirez M, Palmer L, et al. The characterization of pheochromocytoma and its impact on overall survival in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:E1813–9. 10.1210/jc.2013-1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nguyen L, Niccoli-Sire P, Caron P, et al. Pheochromocytoma in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2: a prospective study. Eur J Endocrinol 2001;144:37–44. 10.1530/eje.0.1440037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lairmore TC, Ball DW, Baylin SB, et al. Management of pheochromocytomas in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 syndromes. Ann Surg 1993;217:595–603. 10.1097/00000658-199306000-00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sasaki M, Iwaoka T, Yamauchi J, et al. A case of Sipple’s syndrome with malignant pheochromocytoma treated with 131I-metaiodobenzyl guanidine and a combined chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, vincristine and dacarbazine. Endocr J 1994;41:155–60. 10.1507/endocrj.41.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gentile S, Rainero I, Savi L, et al. Brain metastasis from pheochromocytoma in a patient with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. Panminerva Med 2001;43:305–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gullu S, Gursoy A, Erdogan MF, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A/localized cutaneous lichen amyloidosis associated with malignant pheochromocytoma and ganglioneuroma. J Endocrinol Invest 2005;28:734–7. 10.1007/BF03347557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Namba H, Kondo H, Yamashita S, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 with malignant pheochromocytoma-long term follow-up of a case by 131I-meta-iodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy. Ann Nucl Med 1992;6:111–5. 10.1007/BF03164652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hamdan A, Hirsch D, Green P, et al. Pheochromocytoma: unusual presentation of a rare disease. Isr Med Assoc J 2002;4:827–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spapen H, Gerlo E, Achten E, et al. Pre- and peroperative diagnosis of metastatic pheochromocytoma in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2a. J Endocrinol Invest 1989;12:729–31. 10.1007/BF03350044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hinze R, Machens A, Schneider U, et al. Simultaneously occurring liver metastases of pheochromocytoma and medullary thyroid carcinoma-a diagnostic pitfall with clinical implications for patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2a. Pathol Res Pract 2000;196:477–81. 10.1016/S0344-0338(00)80049-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Averbuch SD, Steakley CS, Young RC, et al. Malignant pheochromocytoma: effective treatment with a combination of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine. Ann Intern Med 1988;109:267–73. 10.7326/0003-4819-109-4-267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deutschbein T, Fassnacht M, Weismann D, et al. Treatment of malignant phaeochromocytoma with a combination of cyclophosphamide, vincristine and dacarbazine: own experience and overview of the contemporary literature. Clin Endocrinol 2015;82:84–90. 10.1111/cen.12590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huang H, Abraham J, Hung E, et al. Treatment of malignant pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine: recommendation from a 22-year follow-up of 18 patients. Cancer 2008;113:2020–8. 10.1002/cncr.23812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:205–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Park KS, Lee JL, Ahn H, et al. Sunitinib, a novel therapy for anthracycline- and cisplatin-refractory malignant pheochromocytoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2009;39:327–31. 10.1093/jjco/hyp005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]