Abstract

Background

Patients with cervical or high thoracic spinal cord injury (SCI) often present reduced gastric emptying and early satiety. Ghrelin provokes motility via gastric vagal neurocircuitry and ghrelin receptor agonists offer a therapeutic option for gastroparesis. We have previously shown that experimental high-thoracic injury (T3-SCI) diminishes sensitivity to another gastrointestinal peptide, cholecystokinin. The present study tests the hypothesis that T3-SCI impairs the vagally-mediated response to ghrelin.

Methods

We investigated ghrelin sensitivity in control and T3-SCI rats at 3-days or 3-weeks after injury utilizing: (i) acute (3-day post-injury) fasting and post-prandial serum levels of ghrelin; (ii) in vivo gastric reflex recording following intravenous or central brainstem ghrelin; and (iii) in vitro whole cell recording of neurons within the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV).

Key Results

The 2-day food intake of T3-SCI rats was reduced while fasting serum ghrelin levels were higher than in controls. Intravenous and fourth ventricle ghrelin increased in vivo gastric motility in fasted 3-day control rats but not fasted T3-SCI rats. In vitro recording of DMV neurons from 3-day T3-SCI rats were insensitive to exogenous ghrelin. For each measure, vagal responses returned after 3-weeks.

Conclusions & Inferences

Hypophagia accompanying T3-SCI produces a significant and physiologically appropriate elevation in serum ghrelin levels. However, higher ghrelin levels did not translate into increased gastric motility in the acute stage of T3-SCI. We propose that this may reflect diminished sensitivity of peripheral vagal afferents to ghrelin or a reduction in the responsiveness of medullary gastric vagal neurocircuitry following T3-SCI.

Keywords: brainstem, gastric emptying, gastric stasis, gastrointestinal motility, vago-vagal reflexes

Graphical abstract

Abbreviated abstract: Brainstem gastric neurocircuitry remains anatomically intact after spinal cord injury (SCI), however, our previous studies suggest that activation of the afferent vagus is compromised in the days to weeks after injury. In a rodent model of SCI, the aim of the present report was to investigate the sensitivity of vagally-mediated gastric contractions to ghrelin. Using in vivo and in vitro neuropharmacological techniques, this study demonstrates that ghrelin sensitivity is blunted in the acute stages of SCI.

Anecdotal reports from the spinal cord injury (SCI) population and the scientific literature suggest a diminished perception of hunger, especially after cervical lesions1. Clinical evidence indicates reduced gastric emptying after T3-SCI2–4 and early satiety that may persist for years after the initial injury5–13. We have demonstrated in a rat model of experimental T3-SCI that ad libitum feeding and gastric motility are diminished beginning immediately after injury14 and that chronic derangements in feeding, gastric motility and emptying persist for 6–18 weeks15,16.

Ghrelin has been identified as the endogenous ligand for growth hormone secretagogue receptor (reviewed in17). During periods when energy balance begins to wane, motilin or the motilin-related peptide ghrelin18,19, is released by the stomach. Exogenous ghrelin promotes feeding behaviors20,21, gastric emptying of either solid22 or liquid meals23, and regular high-amplitude contractions of the stomach and small intestine observed during the inter-digestive phase24. The expression and transport of ghrelin receptors has been documented for the afferent vagus nerve21, and functional studies have confirmed that vagal pathways are integral to ghrelin-induced stimulation of gastric motility21,25–27. Furthermore, the importance of vago-vagal reflex circuits mediating gastric motor function (motility) is well established28. The central, integrative, component of this reflex consists of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV) located within the caudal medulla. Studies over the past decades have led to the generally accepted view that the motor output of the DMV regulates gastric function through the opposing contributions of a cholinergic excitatory and a nonadrenergic, noncholinergic (NANC) inhibitory circuit28,29. Atropine blockade of ghrelin response indicates that cholinergic vagal tone is involved in the gastrointestinal response26,30. It is imperative to note that these vagal pathways remain anatomically intact following T3-SCI.

Prokinetics acting at dopaminergic and serotonergic receptors have been investigated in the clinical SCI literature to accelerate large bowel transit11,31. However, complications due to adverse side effects have limited the clinical utility of these drugs. The prokinetic properties of ghrelin have led to recent proposals for therapeutic targeting with ghrelin agonists17,32–34. However, the diminished ad libitum feeding immediately after T3-SCI14 raises questions of the post-injury sensitivity to endogenous ghrelin. The aims of the present study were to: 1) test the hypothesis that following an overnight fast, serum ghrelin is diminished 3-days after T3-SCI; 2) compare serum ghrelin levels in control rats yoked calorically to ad libitum intake in T3-SCI rats; and 3) test the hypothesis that gastric vagal neurocircuitry is unresponsive to peripherally and centrally administered ghrelin post-SCI.

Materials and Methods

All procedures were performed following National Institutes of Health guidelines and under the oversight of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Penn State University College of Medicine.

Animals

All experiments were conducted on male Long Evans rats (HsdBlu:LE; Envigo Laboratories). Rats (n = 101) were ≥8 weeks of age upon entrance into the experiment and were double housed in a room maintained at 21–24°C and a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with food and water provided ad libitum. Each rat was randomly assigned to one of two surgical manipulations; surgical controls (in which the T3 spinal cord was exposed by laminectomy) or T3-SCI. At the same time, animals were also randomly assigned to one of two post-surgical survival times (3-days or 3-weeks). Following surgical manipulation, rats were housed singly and observed twice a day.

Surgical Procedures and Animal Care

Animals were anesthetized with a 3–5% mixture of isoflurane with oxygen (400–600mL/min) and surgery for T3 contusion SCI was performed using established aseptic surgical techniques. Prior to any surgical manipulation all animals were administered ophthalmic ointment to both eyes, extended-release buprenorphine SR (1mg kg−1, ip, Pfizer Animal Health, Lititz, PA) to alleviate post-operative pain, and antibiotics (Baytril, 10 mg/mL concentration at 1mL kg−1 s.c., Bayer, Shawnee Mission KS) to reduce post-surgical infection.

We performed spinal cord injury at the T2-T3 levels of the vertebral column as described previously35. Briefly, the T2-T3 spinal cord is exposed through a midline incision over the vertebral column, the overlying muscles are detached from the vertebrae and the T2 spinous process is removed with fine tipped rongeurs. The rats are placed in the clamps of the Infinite Horizon controlled impact device (Precision Systems and Instrumentation, LLC, Lexington, KY) whereby a rapid 300 kDyne force (15 second dwell time) of the cord and overlying dura is performed. Procedures for the control animals are the same as for spinal injury except that the spinal cord and surrounding dura mater are not disturbed following laminectomy. Upon completing the surgical procedure, the muscle tissue overlying the lesion site are closed in anatomical layers with Vicryl suture and the skin closed with 9mm wound clips. Animals are administered warmed supplemental fluids (5 cc lactated Ringer’s solution) and placed in an incubation chamber maintained at 37° C until the effects of anesthesia subsided. No rats were removed from the study following post hoc histological verification of lesion severity.

Chronic care of both control and injured animals utilized procedures that have been described previously35. Briefly, post-operative animals are kept in a warm environment and receive subcutaneous supplemental fluids (5–10 cc lactated Ringer’s solution) and antibiotics (Baytril, 10 mg/mL concentration at 1mL kg−1 s.c.) twice daily for 5-days after surgery. Bladder expression and cleaning of the hindquarters is performed at least twice daily in animals with T3-SCI until the return of spontaneous voiding. The ventrum of control animals is inspected daily without need for manual compression of the bladder. In order to assess post-SCI changes in feeding behavior with previously published data14,15, body weight and food intake is recorded each morning and the mean energy intake (MEI) is calculated. The MEI represents the kilocalories consumed per 100g of body weight for each day of monitored feeding.

Serum ghrelin assays

Serum concentration of total ghrelin was quantified by enzyme immunoassay from 3-day T3-SCI and control rats. In the first acute experimental group, 3-day animals (n=8 T3-SCI, n=7 control) were fasted overnight (water ad libitum) prior to ghrelin assay. Following collection of a fasted blood sample, rats were gavage-fed 1 mL of a liquid mixed-nutrient meal (Ensure™). In the second acute experimental group, 3 day control animals (n=6) were matched calorically on the second and third night to the average MEI recorded on the previous night of the 3-day T3-SCI group (n=6). On the morning of the respective test, rats were lightly restrained and approximately 200 μl of blood was collected for assay from a tail nick. Coagulated samples were stored on ice until centrifuged at 4° C (5 min at 2,100 g), blood serum was collected into fresh microcentrifuge tubes, stored (−20°C), and later analyzed in duplicate for serum ghrelin concentration using a commercially available EIA kit (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Burlingame, CA).

In vivo gastric motility recording

Following an overnight fast (water ad libitum), rats were anesthetized deeply with thiobutabarbitol (Inactin®, Sigma; 100–150 mg kg−1 ip). Thiobutabarbitol anesthesia has prolonged duration (>8 hours) with minimal effect upon gastric reflex function.36 Rats were then intubated with a tracheal tube (PE-240, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) to maintain an open airway and permit the clearance of respiratory secretions, a femoral venous catheter (PE-50, Becton Dickinson) was inserted for the intravenous delivery of drugs, and a laparotomy was performed. The stomach was partially exteriorized and a 6 × 8-mm encapsulated sub-miniature strain gage of our own fabrication was aligned with the circular smooth muscle fibers and sutured to the ventral surface of the gastric corpus.37 The strain gage leads were exteriorized before closure of the abdominal incision.

After surgical instrumentation, animals were placed in a stereotaxic frame to reduce the weight strain upon the thoracic cavity and rectal temperature was monitored and maintained at 37±1°C (TCAT 2LV, Physitemp Instruments, Clifton, NJ). The strain gage signal was amplified (QuantaMetrics EXP CLSG-2, Newton, PA) and recorded on a polygraph (model 79, Grass, Quincy, MA) or on a computer using Experimenter’s Workbench software (Datawave Technologies, Loveland, CO). After a minimum 1-hour period of stabilization, defined as a returning to a consistent body temperature of 37°C (particularly necessary for T3-SCI rats) and strain gage signal with little variability over a 30-min period, 10-min of baseline motility was recorded before any experimental manipulation.

In the first series of experiments (3-day post-operative recording: n=7 T3-SCI, n=6 control; 3-week post-operative recording: n=9 T3-SCI, n=6 control), in which the brainstem was not exposed, ghrelin (2.5 μmol kg−1, iv) was continuously infused for a 5-min period. Motility was recorded for the 10-min period immediately preceding infusion, and 10-min immediately following the termination of ghrelin infusion. Gastric motility was analyzed using the motility index originally reported by Ormsbee and Bass38 and described by our laboratory.37 Briefly, the formula for motility index (whereby N equals the total number of peaks in a particular milligram range) is as follows:

Therefore, presuming that a 0 mg signal is indicative of no gastric contractions, the grouping of peak-to-peak sinusoidal signals were calculated as 25–50 mg, 60–100 mg, 110–200 mg and signals greater than 210 mg for N1 through N4, respectively. Unlike area under the curve measurements, the motility index is independent of gradual baseline fluctuations that may occur across several minutes.

In order to control for variability between animals and surgical instrumentation, gastric motility was converted as percent change relative to pre-infusion baseline.

Fourth ventricle/vagal trigone exposure

After a midline incision and removal of the overlying dorsal neck musculature, the head of the animal was oriented in a stereotaxic frame such that the floor of the fourth ventricle was exposed and the brainstem surface was horizontally oriented in a manner that permitted access to obex. The pial membrane overlying the vagal trigone was dissected and the exposed tissues were covered with a warm, saline-infused cotton patch.

In the second series of experiments (3-day post-operative recording: n=7 T3-SCI, n=5 control; 3-week post-operative recording: n=8 T3-SCI, n=6 control), in which the brainstem was exposed, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) vehicle (2 μl) was applied with a Hamilton microsyringe to the surface of the fourth ventricle at the level of the obex in the vicinity of the area postrema and motility signals were acquired as described above. At the conclusion of the control observation period, ghrelin (3–100 pmol in PBS) was applied as described above. Each application of PBS or ghrelin was separated by enough time (minimum of 30 min) for any change in motility to return to baseline. The strain gage output was analyzed for any change in motility for 10-min after each infusion.

Electrophysiology

Brainstem slices were prepared as described previously.39 Briefly, T3-SCI or control rats (n=5 from each post-operative cohort) were anesthetized deeply (Isoflurane, 5%, 1 L min−1 O2) and euthanized via administration of a bilateral pneumothorax. One 3-week sham animal was recorded for basic physiological properties, but could not be perfused with ghrelin. The brainstem was removed and sectioned into 3–4 coronal slices (300μm thick) encompassing the entire rostro-caudal extent of the DVC. Slices were incubated at 30±1°C in Krebs’ solution (in mM: 126 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, and 11 dextrose, maintained at pH 7.4 by bubbling with 95% O2–5% CO2) for at least 60–90 minutes before use. A single slice was then transferred to a perfusion chamber (volume 500μl) which was placed on the stage of a Nikon E600FN microscope and kept in place with a nylon mesh. Brainstem slices were maintained at 35±1°C by perfusion with warmed Krebs’ solution at a rate of 2.5–3.0 mL min−1. Recording parameters have been described previously.39

Histological Processing

At the conclusion of in vivo experiments, deeply anesthetized rats were transcardially perfused with heparinized PBS until fully exsanguinated and followed immediately with PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde. The spinal cords at the lesion level were removed and refrigerated overnight in PBS containing 20% sucrose and 4% paraformaldehyde. For histological staining of T3-SCI lesion extent, tissue was sectioned (40μm thick) and alternating sections were mounted on gelatin coated slides. Spinal cord sections were stained with luxol fast blue for verification of lesion consistency and volume of spared white matter as described previously (see35).

Drugs and chemicals

Inactin® and all other salts were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Ghrelin was purchased from Bachem (Torrence, CA). All drugs were dissolved in sterile isotonic phosphate buffered saline (PBS; in mM: 147.6 NaCl, 83.3 NaH2PO4, 12.9 KH2PO4).

Data analysis and statistics

Individual strain gages were calibrated with a 1-g weight applied externally before and after the experimental procedures. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. Between group results for lesion center, body weight and food intake were evaluated by comparing the change in response between surgical control and T3-SCI by paired t-test; the change in response between pre- and post-treatment values for intravenous ghrelin by one-way ANOVA; and the change in dose response to fourth ventricle ghrelin by repeated measures ANOVA (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Between group results for in vivo serum ghrelin and in vitro studies, with each neuron serving as its own control, were compared before and after ghrelin administration paired t-test (SPSS, Chicago, IL). In all instances, significance was presumed when p < 0.05.

Results

Histological and behavioral assessment following T3-SCI

The severity of experimental T3-SCI was quantified prior to further data analysis. The extent of the lesion epicenter was determined based upon the reduction of LFB-stained white matter at the T3 spinal cord segment (see supplemental Fig. S1). The white matter calculated as percent area of total spinal cord cross-sectional area at the lesion epicenter of 3-day T3-SCI rats was significantly reduced in comparison to T3-control animals (14±3% vs. 76±1%, respectively; p < 0.05). At 3-weeks, when the post-injury progression of the lesion epicenter has relatively stabilized and the lesion boundaries are more clearly defined40, the percent area of white matter at the lesion epicenter of 3-week T3-SCI rats was significantly reduced in comparison to age-matched T3-control animals (11±2% vs. 78±1%, respectively; p < 0.05). These data are comparable to the injury extent reported previously and indicate the severity of our injury model14,41–43. Therefore, all T3-SCI rats were included for analysis.

At 3-days following surgery, the change in body weight between T3-SCI and control animals was −19.5 ± 2.9g vs. −0.5 ± 2.2g, respectively. When normalized as percent of preoperative weight, T3-SCI rats displayed significantly greater weight loss than surgical controls for the comparable time period across the duration of the study (p < 0.05).

Regardless of ease of physical access to chow at bedding level, spontaneous feeding is suppressed following T3-SCI. When normalized as the mean energy intake (MEI; defined as kcal•day−1•100g−1 body weight) the spontaneous feeding for T3-SCI animals in the present study was significantly lower than controls for every comparable time point until the second week of the study (Table 1; p < 0.05).

Table 1.

| MEI (kcal•day−1•100g−1 body weight) is reduced in acute T3-SCI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 days | 1 week | 2 weeks | 3 weeks | |

| Control | 27.6±2.6 | 34.6±2.3 | 31.6±0.2 | 31.7±0.3 |

| T3-SCI | 8.2±1.1* | 20.2±3.1* | 28.7±0.6 | 30.4±0.8 |

p < 0.05 vs control

The reductions in area of intact white matter, body weight and caloric intake is consistent with our previous studies14,15,41, and verify the severity and reproducibility of our surgical procedures for T3-SCI and surgical control animals. Specifically, T3-SCI rats have a persistent reduction in dietary intake during the acute and sub-acute phases (i.e., first two weeks) after injury.

Serum levels of total ghrelin are altered immediately following T3-SCI

Restricted feeding provokes elevated serum ghrelin concentrations in able-bodied subjects while diminished ghrelin levels are associated with reduced dietary intake. The early reduction in spontaneous feeding observed in 3-day T3-SCI rats suggests a possible derangement in normal serum ghrelin availability in the acute T3-SCI rats. The elevation in serum total ghrelin levels of 3-day T3-SCI rats that were fasted overnight was not significantly higher than control (2243.7±539.7 pmol•l−1 vs 1175.9±437.9 pmol•l−1, respectively; p>0.05).

Control animals calorically matched to T3-SCI subjects were fed 8.37±0.4 kcal•day−1•100g body weight−1 compared to the 8.1±2.6 kcal•day−1•100g body weight−1 that was consumed ad libitum by the T3-SCI cohort of rats. The serum total ghrelin levels of 3-day T3-SCI rats was not significantly different from yoke-fed control (120.7±30.2 pmol•l−1 vs 368.6±175.5 pmol•l−1, respectively; p>0.05). These results confirm that the bioavailability of circulating ghrelin is similar in control and T3-SCI rats. Our data further suggest that the significant reduction in ad libitum feeding by T3-SCI rats during the acute (3-day) phase of injury is not likely due to derangements in physiologically relevant levels of ghrelin synthesis or release.

Intravenous ghrelin increases gastric contractions in surgical control but not T3-SCI rats

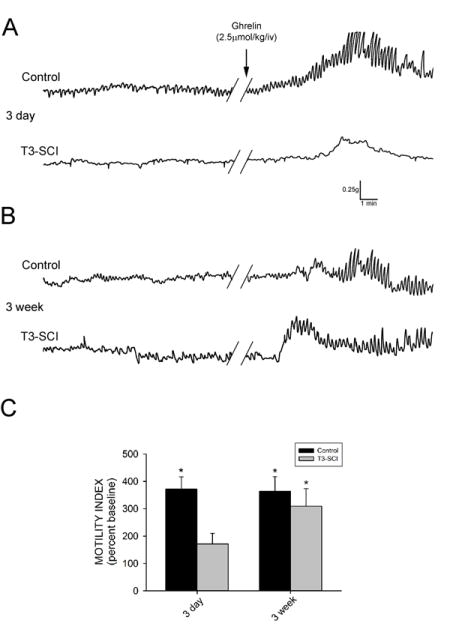

Three days following surgery, there was no significant difference in the baseline motility index between control and T3-SCI rats (p>0.05). Intravenous administration of PBS did not induce any significant change in gastric contractions in either control or T3-SCI rats (p>0.05). Intravenous administration of ghrelin (2.5μmol•kg−1) increased gastric contractions above pre-infusion values in overnight-fasted control rats (p<0.05; Fig. 1A) while the ghrelin-induced increase from baseline was not significant in T3-SCI rats (p>0.05). Subsequently, the motility index of the T3-SCI rats in response to ghrelin was significantly lower than that of control rats (p<0.05; Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Intravenous infusion of ghrelin provokes an increase in gastric contractions in surgical control but not acute T3-SCI rats. A) Representative original polygraph traces from fasted animals tested 3-days after control or T3-SCI surgery. B) Representative traces from fasted animals tested 3-weeks after control or T3-SCI surgery. Baseline motility index had no significant difference between control and T3-SCI in either 3-day or 3-week groups. C) Graphic summary of the significant increase in gastric contractions over baseline (100%, not depicted) following intravenous administration of ghrelin (2.5μmol•kg−1) in 3-day control rats, while the ghrelin-induced increase from baseline was not significant in 3-day T3-SCI rats. Intravenous administration of ghrelin significantly increased gastric contractions above baseline in both 3-week control and 3-week T3-SCI rats. (* p<0.05).

In animals tested three weeks following surgery, there remained no significant difference in the baseline motility index between control and T3-SCI rats (p>0.05). Once again, intravenous administration of PBS did not induce any significant change in gastric contractions in either control or T3-SCI rats (p>0.05). In contrast to the 3-day animals, intravenous administration of ghrelin (2.5μmol•kg−1) in 3-week overnight-fasted animals increased gastric contractions above pre-infusion values in both control and T3-SCI rats (p<0.05; Fig. 1B). Unlike the 3-day animals, the motility index of the control rats in response to ghrelin was not significantly different from that of T3-SCI rats at 3-weeks post-injury (p>0.05; Fig. 1C).

Together, these data suggest that the prokinetic effect of intravenous ghrelin is diminished in the early post-SCI time period. This reduced sensitivity to ghrelin in the SCI subject may be the result of derangements in either peripheral or central neurocircuitry modulating gastric contractions.

Central administration of ghrelin increases gastric contractions in 3 day control but not T3-SCI rats

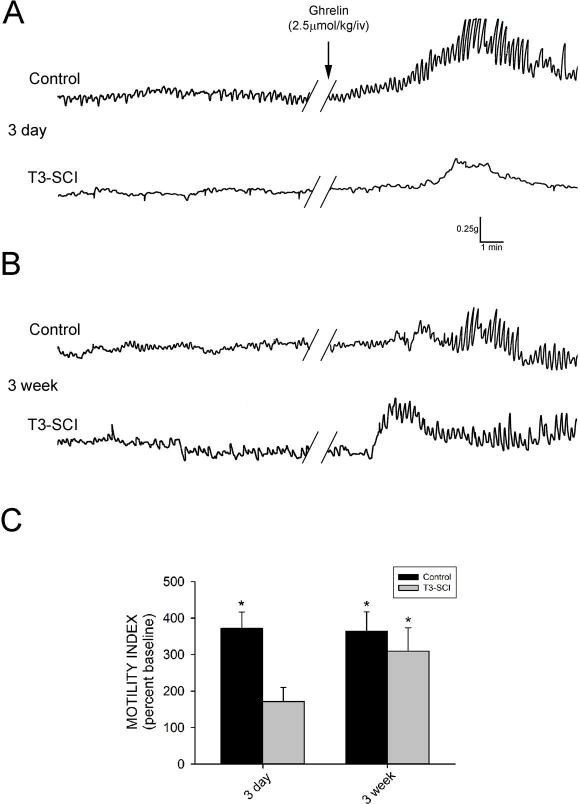

In addition to peripheral activation of the afferent limb of vago-vagal reflex circuitry, circulating ghrelin directly activates gastric neural circuitry within the dorsal vagal complex of neurally intact rats39. Three days following surgery, there was no significant difference in the baseline motility index between control and T3-SCI rats (p>0.05). Fourth ventricle application of PBS did not induce any significant change in gastric contractions in either control or T3-SCI rats (p>0.05).

Fourth ventricle application of ghrelin (3–100 pmol) significantly increased gastric contractions above pre-infusion values in overnight-fasted control rats beginning with the 10 pmol dose (p<0.05; Fig. 2A) while the ghrelin-induced increase from baseline was not significant in T3-SCI rats (p>0.05; Fig. 2A). Subsequently, the motility index of the control rats in response to ghrelin was significantly higher than that of T3-SCI rats beginning with the 10 pmol dose (p<0.05; Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Central (IVth ventricle) administration of ghrelin increases gastric contractions in control but not T3-SCI rats 3-days following surgery. A) Representative traces from fasted animals following 10pmol. While there was no significant difference in baseline motility index between control and T3-SCI rats central application of ghrelin (3–100 pmol) significantly increased gastric contractions beginning at 10 pmol in 3-day control rats while there was no significant difference in gastric contractions of 3-day T3-SCI rats (* p<0.05; B).

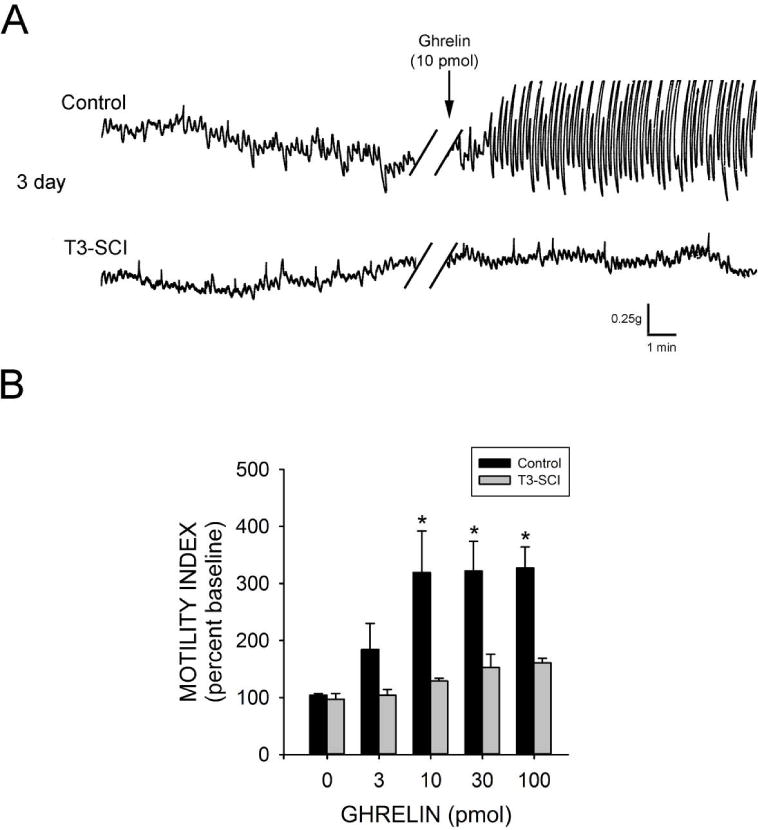

Sensitivity to centrally administered ghrelin returns in 3 week T3-SCI rats

In animals tested three weeks following surgery, there remained no significant difference in the baseline motility index between control and T3-SCI rats (p>0.05). Once again, central application of PBS to the fourth ventricle did not induce any significant change in gastric contractions in either control or T3-SCI rats (p>0.05). In contrast to the 3-day animals, fourth ventricle administration of ghrelin significantly increased gastric contractions above pre-infusion values in both control and 3-week T3-SCI rats, but only at the 100 pmol dose (p<0.05; Fig. 3A). Unlike the 3-day animals, the motility index of the control rats in response to ghrelin was not significantly different from that of 3-week T3-SCI rats (p>0.05; Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

The sensitivity to centrally administered ghrelin returns in 3-week T3-SCI rats. There remained no significant difference in the baseline motility index between 3-week control and 3-week T3-SCI rats. A) Representative traces from fasted animals following 100pmol. While there was no significant difference in baseline motility index between control and T3-SCI rats central application of ghrelin (3–100 pmol) increased gastric contractions but only significantly so at 100 pmol. (* p<0.05; B).

Together, these data suggest that the sensitivity to the prokinetic effect of central ghrelin is diminished in the early post-SCI time period. This reduced sensitivity to ghrelin in the SCI subject may still be the result of derangements in either peripheral terminal afferents to the dorsal vagal complex and/or the central neurocircuitry within the dorsal vagal complex modulating gastric contractions.

T3-SCI does not alter DMV neuron electrophysiological or morphological properties

Whole cell patch clamp recordings from acute (3 day) T3-SCI and control rats identified no changes in the electrophysiological properties of DMV neurons.43 To verify that T3-SCI did not induce any long-term changes, complete electrophysiological properties were assessed in 6 control neurons and 5 T3-SCI neurons. The membrane properties of DMV neurons from control and T3-SCI rats 3-weeks following surgery were assessed under current clamp or voltage clamp conditions as described previously.44 As detailed in Table 2, chronic T3-SCI did not affect either the membrane input resistance or action potential firing properties of DMV neurons.

Table 2.

| Basic membrane properties of DMV neurons remain unchanged | Experimental Groups | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 3 week T3-SCI | |

| (n=6) | (n=5) | |

| Input resistance (MΩ) | 373±45 | 376±62 |

| Action potential duration (ms) | 3.0±0.2 | 2.7±0.2 |

| Afterhyperpolarization amplitude (mv) | 19.7±2.1 | 19.0±2.8 |

| Afterhyperpolarization duration (ms) | 109±23 | 182±96 |

| Action potential firing rate (pps) - 30pA | 3.3±1.4 | 3.0±0.9 |

| Action potential firing rate (pps) - 90pA | 6.3±1.4 | 5.0±1.4 |

| Action potential firing rate (pps) - 150pA | 7.9±1.6 | 7.5±1.4 |

| Action potential firing rate (pps) - 210pA | 8.8±1.9 | 9.0±2.2 |

| Action potential firing rate (pps) - 270pA | 9.2±2.1 | 11.5±2.2 |

These data confirm that the electrophysiological properties of the preganglionic motoneurons of the DMV remain stable following T3-SCI. This suggests that the survival and functional properties of DMV neurons are not adversely affected by the profound and permanent alterations in whole-body physiology following T3-SCI.

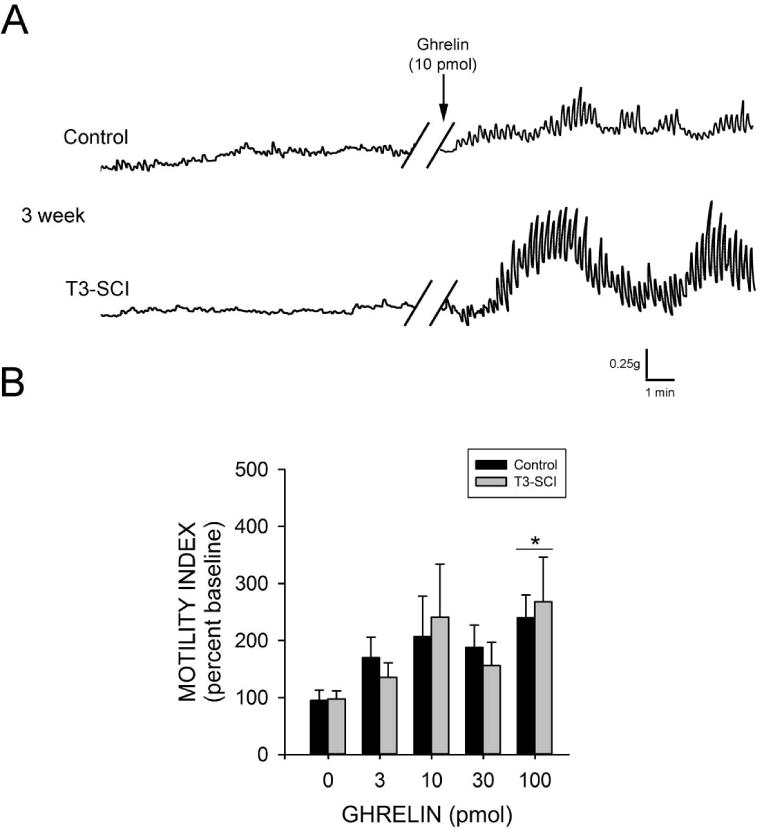

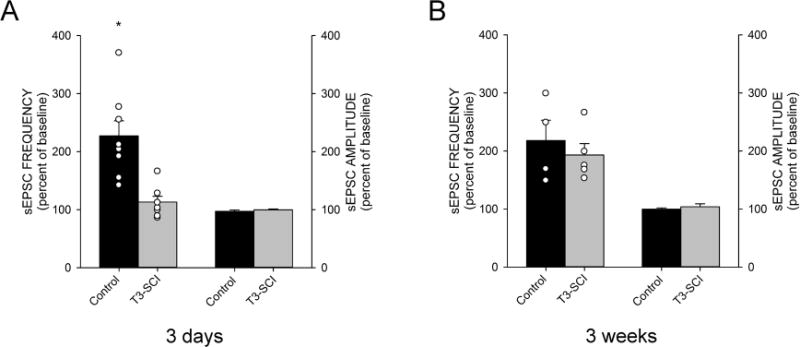

Ghrelin failed to increase sEPSC frequency in DMV neurons from 3-day T3-SCI rats

Ghrelin elevates excitatory glutamatergic pre-synaptic transmission to DMV neurons of naïve rats.39 Similarly, perfusion of ghrelin (100nM) increased the frequency of sEPSC’s from 0.9±0.2 to 1.9±0.4 events s−1 in 8 out of 10 neurons from control rats 3-days following surgery. When expressed as percent change, ghrelin increased sEPSC frequency to 227±26% of control (p < 0.05, Fig. 4A). In these same neurons, ghrelin had no significant effect upon the amplitude of sEPSCs (33.5±1.3pA in control versus 32.5±0.9pA in the presence of ghrelin; p > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Graphical summary of the effects of ghrelin on sEPSCs in DMV neurons of surgical control and T3-SCI rats tested at 3-days (A) or 3-weeks (B). All values represent percent change from control recordings collected prior to bath perfusion with ghrelin (100nM). A) Perfusion of ghrelin significantly increased the sEPSC frequency of surgical control rats 3-days following surgery but had no effect on sEPSC amplitude while at 3-day following T3-SCI, ghrelin failed to increase both the frequency of sEPSC’s and the amplitude in DMV neurons. B) Ghrelin significantly increased sEPSC frequency in DMV neurons from of surgical control rats at 3-weeks after surgery and perfusion with ghrelin also significantly increased sEPSC frequency in 3-week T3-SCI rat DMV neurons. No significant differences were noted in sEPSC amplitudes from either group tested at 3-weeks. Individual data points were omitted from sEPSC amplitude graphs for clarity. (* p<0.05).

Conversely, perfusion with ghrelin had no effect on the frequency of sEPSC’s (1.5±0.3 and 1.8±0.5 events·s−1 in Krebs’ and in 100nM ghrelin, respectively; p > 0.05, Fig. 4A) nor the amplitude (38.1±3.20 and 37.9±2.9pA in Krebs’ and in 100nM ghrelin, respectively; p > 0.05) in 6 out of 7 DMV neurons from T3-SCI rats 3-days after injury.

Ghrelin increased DMV neuron sEPSC frequency of 3-week control and T3-SCI rats

Three weeks following surgery, the action of ghrelin (100nM) increased the frequency of sEPSC’s from 1.3±0.6 to 2.8±0.9 events s−1 in 100% of neurons from 3-week control rats. When expressed as percent change, ghrelin increased sEPSC frequency to 218±35% of control (p < 0.05, Fig. 4B). In these same neurons, ghrelin had no effect upon the amplitude of sEPSCs (32.2±1.2pA in control versus 32.3±2.1pA in the presence of ghrelin; p > 0.05). Similarly, perfusion with ghrelin increased the frequency of sEPSC’s (2.5±0.5 and 4.7±1.1 events·s−1 in Krebs’ and in 100nM ghrelin, respectively; p < 0.05) in 100% of neurons from 3-week T3-SCI rats. When expressed as percent change, ghrelin increased sEPSC frequency to 193±20% of pre-infusion levels (p < 0.05, Fig. 4B). In these same neurons, ghrelin had no effect upon the amplitude of sEPSCs (34.5±1.4 and 35.8±1.5pA in Krebs’ and in 100nM ghrelin, respectively; p > 0.05).

Taken together, these electrophysiological data indicate that the ghrelin-sensitive, action potential-dependent effect of presynaptic glutamate inputs terminating on DMV neurons is transiently disrupted following severe T3-SCI.

Discussion

Our continuing experimental evidence suggests that the gastroparesis associated with T3-SCI may be due to a diminished sensitivity of vago-vagal reflex circuitry to GI peptides. In the present study, our data demonstrate that: 1) intravenous administration of ghrelin fails to elicit contractions of the gastric corpus in T3-SCI rats 3-days following injury; 2) the prokinetic effect of intravenous ghrelin returns to near normal values in rats that have been allowed to recover for three weeks; 3) central administration of ghrelin also fails to increase corpus contractions in T3-SCI rats until three weeks after injury; 3) in vitro recordings confirm that the return of DMV sensitivity to ghrelin after 3-weeks recovery at which time ghrelin, once again, exerts its gastric prokinetic effects by facilitating excitatory synaptic transmission to DMV neurons.

The severity of spinal contusion injury that was verified following the conclusion of these experiments is fundamentally similar to our previous studies in that luxol fast blue-labeled fibers are only observed traversing the perimeter of the T3-SCI lesion epicenter.43 Our previous studies utilizing both contusion SCI and transection SCI determined that only modest differences in the magnitude and duration of post-SCI gastroparesis exist.41 Therefore, we conclude that the severity of our contusion model is similar to our previous studies and neurophysiologically similar to the complete contusion injury that occurs clinically.

Gastrointestinal (GI) motility is the result of an interaction of central- and enteric nervous system circuits. The strength of these two circuits that comprise the gut-brain axis varies with the region of the GI tract (see45). In addition, a large number of neuroendocrine mediators act at multiple levels of the gut-brain axis to regulate GI reflexes and nutrient intake46. In particular, the gastroinhibitory and gastroexcitatory gut-derived peptides cholecystokinin (CCK) and ghrelin (respectively) have received considerable scientific attention and these effects offer well-established pharmacological tools for testing derangements in GI function following SCI. The integrity of the enteroendocrine cells that secrete ghrelin and CCK are dependent on overall health of the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract. Epithelial cell death in response to mesenteric ischemia/reperfusion models has received considerable research focus (see47). Recently, we have reported a reduction in mucosal integrity that is possibly due to a reduction in mesenteric perfusion following T3-SCI.35 While it remains to be determined if there is significant loss of the gastric “X/A” cells responsible for producing ghrelin and the duodenal “I” cells that produce CCK following T3-SCI, our data on serum ghrelin levels indicate that the X/A cells maintain adequate functionality during the acute phase of T3-SCI when gastrointestinal perfusion is significantly compromised.

If serum ghrelin levels in T3-SCI animals are physiologically sufficient, then the mechanism responsible for our reported reduction of a physiological response to exogenous ghrelin may rest within the vago-vagal reflex circuit that mediates gastric contractility. It is well established that gastric reflexes are dominated by this vago-vagal circuit (discussed in39). As with any reflex loop, impairment of afferent and/or efferent signaling can profoundly affect function. The functional integrity of the vagal efferent limb appears unaltered by T3-SCI in that central stimulation of gastric vagal neurocircuitry by the physiologically relevant neuropeptide thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) produced equal levels of gastric contractility in T3-SCI and control rats.43 Therefore, reduction in vagally mediated afferent signaling from the GI tract remains as the most likely mechanism for our observed reduction in ghrelin sensitivity (discussed in48). Vagal afferent dysfunction was inferred in T3-SCI rats following the administration of CCK.42 Specifically, we demonstrated that CCK-8s acted through pre-synaptic inputs to cells within the nucleus tractus solitarius in surgical control animals. This pre-synaptic effect was lost in T3-SCI rat recordings, yet non-specific synaptic transmission in the injured rats was demonstrable following the bath administration of 4-aminopyridine.

An alternative, or parallel, possibility may involve derangements of growth hormone secretagogue receptor-expressing neurons in the area postrema (AP) following T3-SCI.49 Altered neural firing from these GABAergic AP neurons (see50) would conceivably inhibit motility and produce little response to ghrelin-mediated control of gastric emptying, though the percentages of AP neurons demonstrating and increase in firing in the presence of ghrelin were equal to those demonstrating a reduction and make interpretation difficult. While CCK-responsive neurons in the AP are most likely a separate population from growth hormone secretagogue receptor-expressing neurons51, our study of diminished CCK sensitivity following T3-SCI42, included a demonstration of c-Fos immunoreactivity in the dorsal vagal complex (DVC) and the AP. Specifically, the c-Fos expression in the DVC of T3-SCI rats was diminished while AP sensitivity was unchanged. Since the neurophysiological predictions of the present experiments were already established, we did not explore the c-Fos activation of the DVC and AP neurons to ghrelin in this, or our previous ghrelin paper in neurally-intact rats39. Furthermore, our whole-cell in vitro recordings investigating inhibitory currents did not demonstrate any changes in GABAergic synaptic transmission39. Alterations to AP neurophysiology in the T3-SCI model remains a compelling avenue for future studies, but is well beyond the scope of the present report.

Unlike the persistent insensitivity to peripheral and central CCK-8s that was reported in animals tested 3-weeks after T3-SCI,42 the responsiveness to ghrelin was reestablished in our present cohort of 3-week post-injury animals. This restoration of sensitivity to ghrelin occurred both peripherally and centrally. Viewed in context with our present MEI data, this restored sensitivity to ghrelin coincides with the resumption of spontaneous feeding in our T3-SCI rats that is at levels similar to that of surgical controls. While ghrelin exerts profound stimulatory effects upon food intake and energy metabolism at the level of the hypothalamus20,52,53 this stimulatory effect has been demonstrated to also involve a vago-hypothalamic component54. This ascending circuit is robust enough that blockade of vagal afferents eliminated the orexigenic effect of peripheral ghrelin.21 We propose that T3-SCI produces a functionally-similar reduction of vago-hypothalamic stimulation of ingestive behaviors.

One unanswered question pertaining to our data involves any temporal changes in ghrelin receptor expression following T3-SCI. Both ghrelin21 and CCK55,56 receptors are synthesized in the nodose ganglion and transported to sensory terminals and the neurochemical phenotype of vagal afferents is intertwined with nutrient status (see57). Local and systemic inflammatory processes also regulate vagal afferent physiology and response to GI peptides58 and the interaction of the gut microbiome with gut–brain function has recently started to emerge. Each of these processes (microbiome, nutrient intake, and inflammation) is altered in post-SCI physiology57,59,60 and the relative contributions of these changes upon the chemosensory and mechanosensory vagal afferents remains to be determined.

In conclusion, our continuing data suggest that gastroparesis following T3-SCI is due, in part, to diminished sensitivity of vago-vagal neurocircuitry to enteroendocrine signaling molecules, particularly ghrelin and CCK-8s. Vago-vagal neurocircuitry remains anatomically intact following SCI. Therefore, we propose that compromised vagal sensory input affects the gain of vagally-mediated reflexes. In the acute phase, this may consist of a generalized blunting of viscerosensory drive from vagal afferents that drive excitatory (e.g., ghrelin) and inhibitory (e.g., CCK) circuits while recovery of these processes during the chronic phase may not be uniform across the SCI population or even within an individual.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Ghrelin elevates gastric motility via vagal neurocircuitry and ghrelin receptor agonists offer a therapeutic option for gastroparesis after spinal cord injury (SCI)

Circulating and exogenous ghrelin did not translate into increased gastric motility in the acute stage of experimental SCI.

The physiological changes that accompany SCI may include compromised gastric vagally-mediated reflexes that limit the therapeutic efficacy of ghrelin

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge their gratitude to Melissa Tong-Chamberlain and Emily Qualls-Creekmore who provided valuable technical assistance and generation of data on early portions of this study which were initiated at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, Baton Rouge, LA 70808

Dr. Kirsteen N. Browning contributed to the in vitro study design, data generation and data summarization. The authors would also like to express their gratitude to Dr. Victor Ruiz-Velasco and Dr. Salvatore Stella for their collegiality and to Gina Deiter, Margaret S. McLean and Kristy Pugh for their assistance in multiple capacities.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NINDS 49177 (GMH) and NINDS 87834 (EMB as EM Swartz).

Footnotes

Disclosure

No competing interests declared.

Author contribution

EMB acquired and analyzed in vivo experimental data, performed histological processing, and contributed to writing the manuscript. ARW performed histological processing, imaging and data analysis. GMH designed the study and protocol, acquired and analyzed in vivo experimental data, and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Reference List

- 1.Karlsson AK. Autonomic dysfunction in spinal cord injury: clinical presentation of symptoms and signs. Prog Brain Res. 2006;152:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)52034-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirshblum SC, Groah SL, McKinley WO, Gittler MS, Stiens SA. Spinal cord injury medicine. 1. Etiology, classification, and acute medical management. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:S50–S58. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.32156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf C, Meiners TH. Dysphagia in patients with acute cervical spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2003;41:347–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams RE, Bauman WA, Spungen AM, Vinnakota RR, Farid RZ, Galea M, et al. SmartPill technology provides safe and effective assessment of gastrointestinal function in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011;50:81–4. doi: 10.1038/sc.2011.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cosman BC, Stone JM, Perkash I. Gastrointestinal complications of chronic spinal cord injury. J Am Paraplegia Soc. 1991;14:175–81. doi: 10.1080/01952307.1991.11735850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berlly MH, Wilmot CB. Acute abdominal emergencies during the first four weeks after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1984;65:687–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fealey RD, Szurszewski JH, Merritt JL, DiMagno EP. Effect of traumatic spinal cord transection on human upper gastrointestinal motility and gastric emptying. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kao CH, Ho YJ, Changlai SP, Ding HJ. Gastric emptying in spinal cord injury patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1512–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1026690305537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kewalramani LS. Neurogenic gastroduodenal ulceration and bleeding associated with spinal cord injuries. J Trauma. 1979;19:259–65. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197904000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nino-Murcia M, Friedland GW. Functional abnormalities of the gastrointestinal tract in patients with spinal cord injuries: Evaluation with imaging procedures. Am J Roentgenol. 1991;158:279–81. doi: 10.2214/ajr.158.2.1729781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajendran SK, Reiser JR, Bauman W, Zhang RL, Gordon SK, Korsten MA. Gastrointestinal transit after spinal cord injury: Effect of cisapride. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1614–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segal JL, Milne N, Brunnemann SR. Gastric emptying is impaired in patients with spinal cord injury. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:466–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stinneford JG, Keshavarzian A, Nemchausky BA, Doria MI, Durkin M. Esophagitis and esophageal motor abnormalities in patients with chronic spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia. 1993;31:384–92. doi: 10.1038/sc.1993.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong M, Holmes GM. Gastric dysreflexia after acute experimental spinal cord injury in rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Primeaux SD, Tong M, Holmes GM. Effects of chronic spinal cord injury on body weight and body composition in rats fed a standard chow diet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1102–R1109. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00224.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qualls-Creekmore EQ, Tong M, Holmes GM. Time-course of recovery of gastric emptying and motility in rats with experimental spinal cord injury. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanger GJ, Furness JB. Ghrelin and motilin receptors as drug targets for gastrointestinal disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:38–48. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656–60. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inui A, Asakawa A, Bowers CY, Mantovani G, Laviano A, Meguid MM, et al. Ghrelin, appetite, and gastric motility: the emerging role of the stomach as an endocrine organ. The FASEB Journal. 2004;18:439–56. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0641rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakazato M, Murakami N, Date Y, Kojima M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K, et al. A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 2001;409:194–8. doi: 10.1038/35051587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Date Y, Murakami N, Toshinai K, Matsukura S, Niijima A, Matsuo H, et al. The role of the gastric afferent vagal nerve in ghrelin-induced feeding and growth hormone secretion in rats. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1120–8. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukuda H, Mizuta Y, Isomoto H, Takeshima F, Ohnita K, Ohba K, et al. Ghrelin enhances gastric motility through direct stimulation of intrinsic neural pathways and capsaicin-sensitive afferent neurones in rats. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1209–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levin F, Edholm T, Ehrstrom M, Wallin B, Schmidt PT, Kirchgessner AM, et al. Effect of peripherally administered ghrelin on gastric emptying and acid secretion in the rat. Regul Pept. 2005;131:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ariga H, Nakade Y, Tsukamoto K, Imai K, Chen C, Mantyh C, et al. Ghrelin accelerates gastric emptying via early manifestation of antro-pyloric coordination in conscious rats. Regul Peptides. 2008;146:112–6. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang WG, Chen X, Jiang H, Jiang ZY. Effects of ghrelin on glucose-sensing and gastric distension sensitive neurons in rat dorsal vagal complex. Regul Peptides. 2008;146:169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams DL, Grill HJ, Cummings DE, Kaplan JM. Vagotomy Dissociates Short- and Long-Term Controls of Circulating Ghrelin. Endocrinology. 2003;144:5184–7. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cabral A, Cornejo MaP, Fernandez G, De Francesco PN, Garcia-Romero G, Uriarte M, et al. Circulating Ghrelin Acts on GABA Neurons of the Area Postrema and Mediates Gastric Emptying in Male Mice. Endocrinology. 2017;158:1436–49. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Travagli RA, Hermann GE, Browning KN, Rogers RC. Brainstem circuits regulating gastric function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:279–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040504.094635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang HY, Mashimo H, Goyal RK. Musings on the wanderer: what’s new in our understanding of vago-vagal reflex? IV. Current concepts of vagal efferent projections to the gut. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G357–G366. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00478.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masuda Y, Tanaka T, Inomata N, Ohnuma N, Tanaka S, Itoh Z, et al. Ghrelin stimulates gastric acid secretion and motility in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:905–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segal JL, Milne N, Brunnemann SR, Lyons KP. Metoclopramide-induced normalization of impaired gastric emptying in spinal cord injury. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:1143–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venkova K, Fraser G, Hoveyda HR, Greenwood-Van MB. Prokinetic effects of a new ghrelin receptor agonist TZP-101 in a rat model of postoperative ileus. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2241–8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Smet B, Mitselos A, Depoortere I. Motilin and ghrelin as prokinetic drug targets. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;123:207–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trudel L, Tomasetto C, Rio MC, Bouin M, Plourde V, Eberling P, et al. Ghrelin/motilin-related peptide is a potent prokinetic to reverse gastric postoperative ileus in rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G948–G952. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00339.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Besecker EM, Deiter GM, Pironi N, Cooper TK, Holmes GM. Mesenteric vascular dysregulation and intestinal inflammation accompanies experimental spinal cord injury. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2017;312:146–56. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00347.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qualls-Creekmore E, Tong M, Holmes GM. Gastric emptying of enterally administered liquid meal in conscious rats and during sustained anaesthesia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01393.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holmes GM, Swartz EM, McLean MS. Fabrication and implantation of miniature dual-element strain gages for measuring in vivo gastrointestinal contractions in rodents. J Vis Exp. 2014;31:1563–80. doi: 10.3791/51739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ormsbee HS, Bass P. Gastroduodenal motor gradients in the dog after pyloroplasty. Am J Physiol. 1976;230:389–97. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.2.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swartz EM, Browning KN, Travagli RA, Holmes GM. Ghrelin increases vagally-mediated gastric activity by central sites of action. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;125:2–22. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill CE, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC. Degeneration and sprouting of identified descending supraspinal axons after contusive spinal cord injury in the rat. Exp Neurol. 2001;171:153–69. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qualls-Creekmore E, Tong M, Holmes GM. Time-course of recovery of gastric emptying and motility in rats with experimental spinal cord injury. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:62–e28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tong M, Qualls-Creekmore E, Browning KN, Travagli RA, Holmes GM. Experimental spinal cord injury in rats diminishes vagally-mediated gastric responses to cholecystokinin-8s. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:e69–e79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swartz EM, Holmes GM. Gastric vagal motoneuron function is maintained following experimental spinal cord injury. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;27:2–7. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Browning KN, Renehan WE, Travagli RA. Electrophysiological and morphological heterogeneity of rat dorsal vagal neurones which project to specific areas of the gastrointestinal tract. J Physiol. 1999;517(Pt 2):521–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0521t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furness JB, Callaghan BP, Rivera LR, Cho HJ. The enteric nervous system and gastrointestinal innervation: integrated local and central control. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;817:39–71. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0897-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moran TH. Neural and Hormonal Controls of Food Intake and Satiety. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. 4th. New York: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 877–94. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Granger DN, Holm L, Kvietys P. The Gastrointestinal Circulation: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Compr Physiol. 2015;5:1541–83. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holmes GM. Upper gastrointestinal dysmotility after spinal cord injury: Is diminished vagal sensory processing one culprit? Front Physiol. 2012;3:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zigman JM, Jones JE, Lee CE, Saper CB, Elmquist JK. Expression of ghrelin receptor mRNA in the rat and the mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2006;494:528–48. doi: 10.1002/cne.20823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fry M, Ferguson AV. Ghrelin modulates electrical activity of area postrema neurons. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2009;296:R485. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90555.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lutz TA. Amylinergic control of food intake. Physiology & Behavior. 2006;89:465–71. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cowley MA, Smith RG, Diano S, Tsch+¦p M, Pronchuk N, Grove KL, et al. The Distribution and Mechanism of Action of Ghrelin in the CNS Demonstrates a Novel Hypothalamic Circuit Regulating Energy Homeostasis. Neuron. 2003;37:649–61. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heppner KM, Müller TD, Tong J, Tschöp MH. Ghrelin in the Control of Energy, Lipid, and Glucose Metabolism. Methods Enzymol. 2012;514:249–60. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381272-8.00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Date Y, Shimbara T, Koda S, Toshinai K, Ida T, Murakami N, et al. Peripheral ghrelin transmits orexigenic signals through the noradrenergic pathway from the hindbrain to the hypothalamus. Cell Metab. 2006;4:323–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moran TH, Smith GP, Hostetler AM, McHugh PR. Transport of cholecystokinin (CCK) binding sites in subdiaphragmatic vagal branches. Brain Research. 1987;415:149–52. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moriarty P, Dimaline R, Thompson DG, Dockray GJ. Characterization of cholecystokininA and cholecystokininB receptors expressed by vagal afferent neurons. Neuroscience. 1997;79:905–13. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00675-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dockray GJ, Burdyga G. Plasticity in vagal afferent neurones during feeding and fasting: mechanisms and significance. Acta Physiologica. 2011;201:313–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Lartigue G, de La Serre CB, Raybould HE. Vagal afferent neurons in high fat diet-induced obesity; intestinal microflora, gut inflammation and cholecystokinin. Physiology & Behavior. 2011;105:100–5. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kigerl KA, Hall JCE, Wang L, Mo X, Yu Z, Popovich PG. Gut dysbiosis impairs recovery after spinal cord injury. J Exp Med. 2016 doi: 10.1084/jem.20151345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feldman-Goriachnik R, Belzer V, Hanani M. Systemic inflammation activates satellite glial cells in the mouse nodose ganglion and alters their functions. Glia. 2015;63:2121–32. doi: 10.1002/glia.22881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.