Abstract

Nanoengineering of cell membranes holds great potential to revolutionize tumor-targeted theranostics, owing to their innate biocompatibility and ability to escape from immune and reticuloendothelial systems. However, tailoring and integrating cell membranes with drug and imaging agents into one versatile nanoparticle is still challenging. Here, multicompartment membrane-derived liposomes (MCLs) are developed by reassembling cancer cell membranes with Tween-80 for the first time, and are used to conjugate 89Zr via deferoxamine chelator and load tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (TCPP) for in vivo non-invasive quantitative tracing by positron emission tomography (PET) imaging and photodynamic therapy (PDT), respectively. Radiolabeled constructs, 89Zr-Df-MCLs, demonstrate excellent radiochemical stability in vivo, target 4T1 tumors by the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, and are retained over long-term for efficient and effective PDT while clearing gradually from the reticuloendothelial system via hepatobiliary excretion. Toxicity evaluation confirms MCLs do not impose acute or chronic toxicity in intravenously-injected mice. Additionally, 89Zr-labeled MCLs can execute rapid and highly sensitive lymph node mapping, even for deep-seated sentinel lymph nodes. As-developed cell membrane reassembling route to MCLs could be extended to other cell types, providing a versatile platform for disease theranostics by facilely and efficiently integrating various multifunctional agents.

Keywords: membrane-derived liposomes, cancer cell membranes, cancer theranostics, targeted drug delivery, positron emission tomography

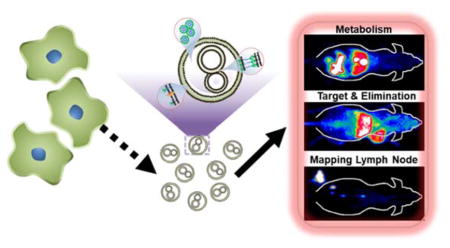

Graphical abstract

Systematic non-invasive tracking and quantitative investigation of 89Zr-Df-MCLs is performed to demonstrate rapid clearance of 89Zr-Df-MCLs: estimated to be over 63 %ID at 72 h post-injection through hepatobiliary route.89Zr-Df-MCLs are developed as PET contrast agents for in vivo imaging of tumors and mapping of lymph nodes, as well as for fluorescence imaging and photodynamic therapy after loading with porphyrin cargo.

The biomedical applications of nanotechnology are expected to revolutionize cancer diagnosis and therapy potently.[1, 2] In theory, an ideal nanoplatform should be non-toxic as well as invisible to the immune system, thus providing long systemic circulation to maximize drug delivery to the targeted site.[3, 4] However, the limited biomimetic functions of artificial nanoplatforms remain inadequate in overcoming fast clearance by the reticuloendothelial system (RES)/mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS).[5]

Recently, cell membrane-based nanoplatforms have gained much attention owing to their distinct advantages such as excellent biocompatibility, low toxicity, high tumor accumulation, and innate ability to evade the RES.[6, 7] There are several typical approaches involving the utilization of cell membranes for construction of theranostic nanoparticles, including red blood cell membrane-encapsulated nanoparticles,[8–10] cancer cell membrane-fabricated nanoparticles,[11, 12] and platelet cell-cloaked nanoparticles.[13, 14] These strategies endow cell membrane-modified nanoparticles with some unique biofunctions including the enhancement of anticancer immunity through activation of the immune system, self-stealth by bypassing immune recognition and self-targeting based on homotypic recognition of circulating tumor cells.[15]

Although many advances in nanoengineering of biomembranes have been achieved, accurate pharmacokinetic understanding of these cell membrane-based nanoplatforms (CMNs) is still evasive, mostly because optical imaging, the commonly employed modality of investigation, suffers from semi-quantitative nature and limited depth of penetration. [13, 16, 17] and, invasive methods such as ICP require the sacrifice of many animals.[3, 11] Knowledge of CMN pharmacokinetics can help researchers to improve the design of CMNs. Thus, there is a need for quantitative, non-invasive, accurate and long-term imaging of CMNs to assess their biodistributions and trace their metabolism in vivo. Compared to other imaging techniques, positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has high detection sensitivity, unlimited signal penetration, and excellent quantitative capability, obtaining more widespread use in both preclinical and clinical scenarios.[19–21] Therefore, it is conceivable to integrate PET imaging functionality into CMNs for real-time, accurate, and quantitative tracing of their behavior in vivo.

In this work, a cell membrane reassembling (CMR) methodology was developed to synthesize novel multicompartment membrane-derived liposomes (MCLs) by integrating Tween-80 into cancer cell membranes. The CMR method is facile and efficient as it is easy to prepare and purify cancer cell membranes and incorporate them with biocompatible surfactants such as Tween-80. [22–24] Importantly, unlike cloaking of synthetic nanoparticles with CMNs that may cause toxicity concerns from enhanced RES uptake and slower clearance,[18] as-obtained MCLs are highly compatible, capable of enhanced tumor targeting, rapid clearance from normal organs. In addition, the MCLs are versatile in terms of stable radiotracer labeling and high drug loading capacity, owing to their multifunctional surface and multicompartment structure. Accordingly, Tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (TCPP) was loaded into the MCLs, both as a fluorescence agent and a model drug for photodynamic therapy (PDT). MCLs were further conjugated with p-SCN-deferoxamine (Df-MCL) as a chelator for PET isotope, zirconium-89 (89Zr) to form the final radiostable nanoconstruct, 89Zr-Df-MCL, via addition and intensive coordination reactions.89Zr has a relatively long half-life (t1/2 = 78.4 h) and a low positron energy,[25–27] making it particularly suitable for long-term in vivo tracking with PET imaging.

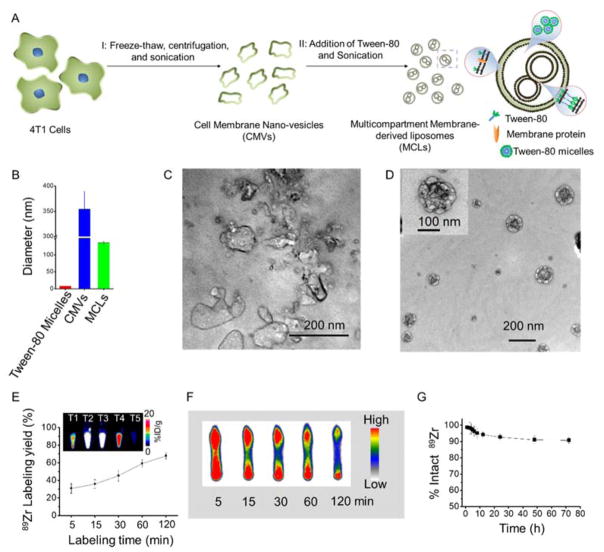

As demonstrated in Figure 1A, MCLs were prepared by fusing 4T1 cancer cell membranes with the surfactant Tween-80 in different ratios by the CMR method, (Experimental section S1, Supporting Information). Firstly, 4T1 cancer cell membranes were obtained by a repeated freeze-thaw process, followed by washing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). As-obtained 4T1 cancer cell membranes were suspended in pure water and sonicated for 5 min at a frequency of 42 kHz and a power of 100 W to obtain cell membrane nano-vesicles (CMVs). The size and morphology of these cell membrane nano-vesicles were tested by dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurement and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). As shown in Figure 1B, 1C and S1 (blue curve), the CMVs demonstrated irregular morphology with an average diameter ~ 350 nm and a wide size distribution.. According to the mechanism for liposome formation, a mixture of two surfactants with different interface energies can form a high curvature of the two-layer membranes, thus generating nanosized liposomes. Thus, we hypothesized that the curvature of a bilayer cell membrane might become high enough to form nanosized membrane-derived liposomes after incorporating with the surfactant Tween-80 which has a different interface energy from the cell membrane. As-prepared CMVs were mixed with Tween-80 micelles (~ 8 nm) and the reassembly process was found to depend acutely on the weight ratios between Tween-80 and the CMVs. Low mixing ratios of Tween-80 to CMV (upto 0.3:1) were found to be insufficient to change the irregularity of CMVs and resulted in incomplete formation of membrane-derived liposomes. (Figure S2 A,B) Interestingly, a 0.6:1 Tween-80: CMV weight ratio yielded reassembled membrane-derived liposomes with uniform multicompartment nanostructures, regular spherical morphology and an average diameter of 140 nm (Figure 1D). The multicompartment structure of the reassembled membrane-derived liposomes can be attributed to the inhomogeneity of the cracked cell membranes. Increasing the ratio ratio of ~ 1.5:1 finally transformed MCLs into an ultrasmall single compartment liposome ~ 10 nm in diameter. (Figure S2C). MCLs generated with a 0.6:1 reassembly ratio between Tween-80 and CMVs were chosen for further studies. Fluorescence staining confirmed the complete removal of cell nucleus in the MCLs (Figure S3) Additionally, the obtained MCLs were stable for up to 14 days both in the fetal bovine serum (FBS) and PBS (Figure S4).

Figure 1.

Preparation and 89Zr-labeling of MCLs. (A) A schematic illustration of MCL fabrication. (B) The particle diameter of tween-80 micelles, cell membrane nano-vesicle (CMVs), and MCLs. (C, D) TEM imaging of CMVs and MCLs. (E) Time-dependent 89Zr labeling yields of Df-MCLs. The inset photo represents PET images of different fractions collected after PD-10 purification of Df-MCLs incubated with 89Zr for 2 h. (F) Autoradiograph of TLC plates of 89Zr-Df-MCLs at different incubation time points. (G) Serum stability study of 89Zr-Df-MCLs.

To non-invasively track and quantitatively investigate the misdistribution of MCLs, they were conjugated with p-SCN-deferoxamine (Df) via the amine groups of proteins in the bilayer (Df-MCLs),[30, 31] followed by radiolabeling with 89Zr(89Zr-Df-MCLs).[32] 89Zr was mixed with Df-MCL in HEPES buffer (50 mM) at pH ≈7 and incubated at 37 °C for varying lengths of time. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) indicated time-dependent radiolabeling yields. (Figure S5 A) 89Zr could be chelated to Df-MCLs within 5 min of incubation, with a final radiolabeling yield of ~ 67.9 % after 2 h of incubation. (Figure 1E and 1F) The final product was purified with the PD-10 columns prior to injections. (Figure S5B) The highest radioactivity fractions were found to elute between 3.0–3.5 mL and 3.5–4.0 mL as shown in the inset images of Figure 1E. Importantly, neither pure Tween-80 micelles nor CMVs were found to intrinsically chelate 89Zr (Figure S6). TEM demonstrated no significant difference in the morphology and structure of 89Zr-Df-MCLs and MCLs (Figure S7). The 89Zr labeling on Df-MCLs was also found to be highly stable in mouse serum for up to 72 h (Figure 1G). Overall, the high labeling yields and radiostability of 89Zr-Df-MCL, make it promising platform for in vivo PET imaging.

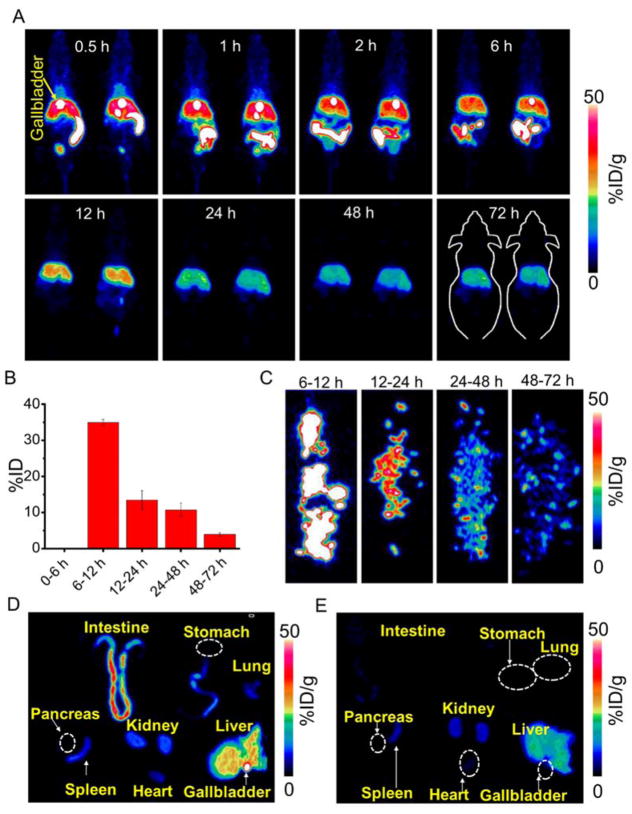

To investigate the misdistribution and pharmacokinetic properties of MCLs in vivo, the distribution/clearance profiles of 89Zr-Df-MCLs were examined in Balb/c mice after intravenous injection, via serial PET imaging at designated time-points, for up to 72 h post-injection (p.i.), taking advantage of the long half-life of 89Zr (t1/2 = 78.4 h). PET imaging showed strong signal from the liver, the gallbladder, and the intestine within 0.5 h p.i.. Importantly, the bright gallbladder inside the liver implies that 89Zr-Df-MCLs are excreted out by the hepatobiliary system (Figure 2A). At the same time, only the upper section of the intestine shows a strong signal. As shown in PET images, the signal of the gallbladder decreases or disperses, which presents individual differences between the animals. It is found the PET signal reaches the rectum as early as 6 h p.i., while the signal from the intestine disappears after 12 h p.i.. Through the PET observations, the signal from the liver can be partly ascribed to the presence of blood in the liver, as the liver is a major blood pool in vivo [33]. It can also be concluded that the excretion of 89Zr-Df-MCLs along with the feces begins during the first 12 h p.i.. Region-of-interest (ROI) analyses of PET data and time-activity curves of the liver, intestine, gallbladder, blood, spleen, and muscle were performed post-injection of 89Zr-Df-MCLs, and the results are shown in Figure S8A–C. Quantitative ROI analysis revealed that the gallbladder uptake was 64.5±3.2, 56.9±5.0, 43.5±6.6, 33.2±11.9, 4.6±0.6, 0.03±0.01, 0.03±0.02, and 0.01±0.01 %ID/g at 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h p.i., respectively (n = 3). Herein, besides the high gallbladder uptake, a significant signal in the intestine could be attributed to the excretion of 89Zr-Df-MCLs through the liver/gallbladder system. The ROI intestine signals were found to be 42.9±3.6, 55.3±2.8, 57.8±2.6, 51.8±2.3, 5.6±2.6, 1.6±0.4, 1.3±0.4, and 0.7±0.2 %ID/g at 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h p.i., respectively (n = 3). This result is in line with the radioactivity curve of the gallbladder. Besides high gallbladder uptake and intestine PET signal, the accumulation of 89Zr-Df-MCLs could also be observed in the liver, whose radioactivity peaks at 35.0±4.6 %ID/g at 0.5 h p.i., and significantly decreased to 20.8±2.7 %ID/g at 24 h p.i. Finally, the radioactivity decreases to 11.3±1.4 %ID/g at 72 h p.i. (n = 3). the mice were sacrificed after the final scans at 72 h p.i. and all the main organs were collected, wet-weighed, and measured with a gamma counter. Figure S8D presents the ex vivo misdistribution of 89Zr-Df-MCLs in mice. The dominant accumulation of nanoparticles were found in the liver (10.9±1.5 %ID/g), spleen (8.6±2.5%ID/g), and kidney (3.9±1.1% ID/g) (n = 3). The misdistribution results show comparatively low values in other organs.

Figure 2.

Misdistribution and hepatobiliary excretion of 89Zr-Df-MCLs. (A) In vivo serial PET images of mice taken at various time points (0.5, 1, 2, 5, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h) post intravenous injection of 89Zr-Df-MCLs. Organ uptake was presented as %ID/g. (B) The hepatic clearance of 89Zr-Df-MCLs excreted in the feces at various time points p.i. The data is presented as %ID. (n=3) (C) PET images of feces taken at various time points. Ex vivo PET imaging of main organs at different time points p.i. (D) 1 h, and (E) 24 h.

To confirm the excretion of 89Zr-Df-MCLs along with the feces, a metabolic cage study was performed to quantitatively study the hepatobiliary clearance rates of 89Zr-Df-MCLs in mice. As shown in Figure 2B, the feces were collected at different time-points and measured separately using a gamma counter. Based on the in vivo PET imaging studies, no radioactive 89Zr-Df-MCLs were found to be excreted out of the mice in the feces during the early time points upto 6 h, possibly due to difficulty in collecting feces at early time-points. Dominant hepatobiliary clearance was observed with the feces uptake measured to be 35.0 ± 0.9 %ID (at 12 h p.i.), nearly 10 times higher than that at 72 h time point (3.8 ± 0.5 %ID) (n = 3). The total clearance of 89Zr-Df-MCLs was estimated to be over 63 %ID at 72 h p.i. PET imaging of the collected feces also showed that dominant clearance was observed at the 12 h time point (Figure 2C and Figure S9).

To accurately estimate the metabolic behavior of 89Zr-Df-MCLs in the intestine, the main organs (intestine, stomach, liver, heart, spleen, lung and kidney) of the mice were harvested, and ex vivo PET and bright field imaging were performed at designated time intervals (1 h, and 24 h). It was found that, at 1 h p.i., a strong radioactive signal emerges from the gallbladder and intestine of 89Zr-Df-MCL-injected mice, confirming the excretion the hepatobiliary system (Figure 2D and E, and Figure S10 A and B). In Figure 2D and Figure S10C, only the upper section of the intestine shows the radioactive signal. To identify the organs, the maximum scale bar was reduced to 10 %ID/g (Figure S10 C and D). ROI analysis revealed good agreement with that of the ex vivo misdistribution result (Figure S11). In contrast, the recorded images at 24 h p.i. detect only very weak signal (Figure 2E, and Figure S10 D), suggesting that most of the injected 89Zr-Df-MCLs were excreted out. This result verifies that the radioactive signal observed from the intestine in Figure 2A is emitted by the 89Zr-Df-MCLs in the feces and no reabsorption of 89Zr-Df-MCLs by the intestine has taken place.

According to the above result, 89Zr-Df-MCLs mainly accumulated in the liver. To further confirm their biosafety, MCLs were injected into the healthy Balb/c mice at the dose of 450 mg/kg. The primary liver function markers including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and total bilirubin, as well as kidney function markers, including serum creatinine, were all measured. No noticeable toxic side effects were found in the Balb/c mice based on the serum biochemistry analysis (Figure S12A and S12B). On Day 14, major organs (i.e., heart, liver, spleen, kidneys) were collected and stained with H&E for histology analysis. The results in Figure S12 C further reveal no noticeable tissue damage in the primary organs of healthy mice. Combined with retention profiles acquired from PET, it may be reasonable to conclude that MCLs would not cause significant long-term toxicity in vivo.

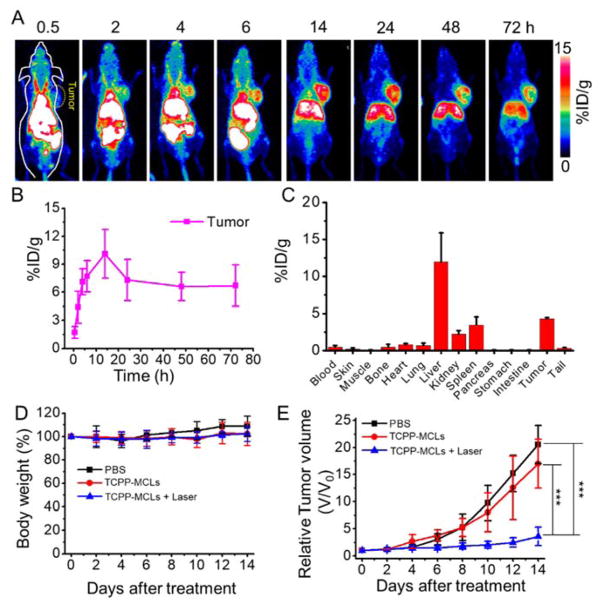

To demonstrate the feasibility of using MCLs for passive-targeting of tumors by the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect [34], and to investigate in vivo misdistribution of MCLs in tumor-bearing mice, 89Zr-Df-MCLs were injected into Balb/c mice bearing 4T1 tumors (Figure 3A). Interestingly, 89Zr-Df-MCLs showed efficient tumor accumulation, demonstrating a time-dependent increase after injection. Quantitative data obtained from ROI analysis revealed that the tumor uptake of 89Zr-Df-MCLs was 4.4±1.7, 7.1±1.4, 7.7±1.7, 10.1±2.6, 7.3±2.2, 6.6±1.5, and 6.7±2.2 %ID/g (n = 3) at 2, 4, 6, 14, 24, 48, and 72 h p.i., respectively (Figure 3B), indicating enhanced tumor uptake mediated by the EPR effect in 4T1 tumors. Strong PET signals in the blood even at 14 h time point suggested a prolonged blood circulation time, resulting in the strong EPR-dependent tumor uptake of 89Zr-Df-MCLs. Besides the efficient tumor uptake, significant radioactivity was also found in the gallbladder, liver, and intestine, in accordance with our previous observations.

Figure 3.

Tumor targeting and in vivo anti-tumor therapy of 89Zr-Df-MCLs. (A) In vivo PET images of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice taken at various time points post intravenous injection of 89Zr-Df-MCLs. (B) Quantification of 89Zr-Df-MCLs uptake in the tumor at various time points p.i. The unit is the percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g) (n=3). (C) Misdistribution of 89Zr-Df-MCLs 72 h after intravenous injection into 4T1 tumor-bearing mice as determined by 89Zr radioactivity measurements in various organs (n=3). (D) Body weight measurements after various treatments showed no significant toxicity (n=5–6). (E) Tumor growth profiles of 4T1 tumors after each treatment. For the combination treatment group, six mice injected with TCPP-MCLs were irradiated with 660 nm laser (50 mW/cm2, 40 min) at 24 h p.i.. Two groups of mice were used as controls: untreated (PBS) (n=5); and TCPP-MCLs only without laser treatment (n=6). (***p < 0.001).

Ex vivo misdistribution study corroborated well with the imaging analyses. (Figure 3C) Besides 4.3±0.1 %ID/g tumor uptake, the nanoparticles were found to be dominantly accumulated in the excretory organs along with the liver (11.9±3.5 %ID/g), spleen (3.4±3.0 %ID/g) and kidney (2.2±0.5%ID/g) (n = 3). Off-target accumulation of 89Zr-Df-MCLs remained negligible in all the other organs.

Encouraged by the excellent tumor-homing capacility of MCLs, we further evaluated the potential anticancer application of MCLs mediated by the loaded cargo, TCPP. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (n = 5–6 for all groups) was performed using TCPP-loaded MCLs (loading ratio of 1.3 wt%, denoted as TCPP-MCLs), PBS, and combination treatment of TCPP-MCLs and laser irradiation (denoted as combination group) at the same TCPP concentration. The mice bearing 4T1 tumors were intravenously injected with TCPP-MCLs (200 μL, 2 mg/mL). As shown in Figure S13 A, in vivo fluorescence imaging confirmed that TCPP was indeed delivered into the tumor by MCLs after 24 h p.i. In contrast, no fluorescence signal was observed in mice injected with TCPP-micelles (a solution of Tween-80 micelles loaded with TCPP) group. Ex vivo imaging at 24 h p.i. revealed that fluorescence signals of TCPP-MCLs were mainly found in the intestine, liver and tumor tissues (Figure S13 B). Thus, at 24 h p.i., the combination group was exposed to a 660 nm laser at a power density of 50 mW/cm2 for 40 min. After 14 days of treatment, the combination treatment group showed remarkable tumor inhibition effects (Figure 3E and Figure S14). No distinct change in body weights was observed for each group, indicating tolerable safety profile of the treatment. (Figure 3D) These preliminary results suggest the promising potential of MCLs as a drug carriers for cancer-targeted therapy.

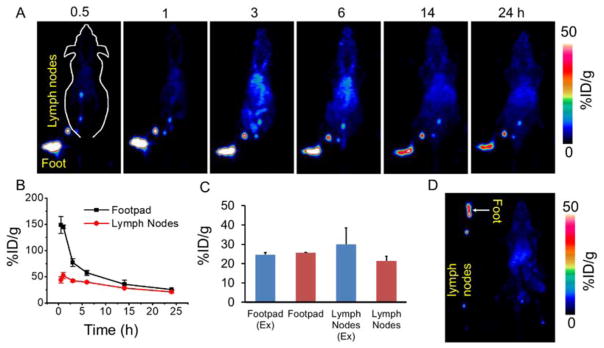

Sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs) are a typical route for tumor metastasis, and precise and early identification of SLNs has been considered necessary for assessing tumor prognosis in clinical treatment as well as prediction of cancer metastasis [35, 36]. In the clinic, SLN mapping is realized via colored dyes or carbon black injected into the solid tumor, whose draining lymph nodes are then lighted up. [37, 38]. However, the sensitivity of this method is limited. Previous studies have demonstrated that nanoparticles > 4 nm in diameter can rapidly enter the lymphatic capillaries and result in efficient labeling of the vessels and the sentinel lymph nodes [36]. As a proof-of-concept, herein we demonstrate the possibility of using 89Zr-Df-MCLs probes for highly sensitive in vivo lymph node mapping via non-invasive PET imaging. Upon local injection with 89Zr-Df-MCLs into the footpad of each mouse, serial PET scans were performed (Figure 4A). An extensive draining lymphatic network containing multiple deep-seated lymph nodes lightened up as early as 0.5 h p.i. of 89Zr-Df-MCL. The signals in those lymph nodes remained very obvious even 24 h after local injection (Figure 4B,C and D), further demonstrating the excellent potential of 89Zr-Df-MCLs for early, persistent and rapid mapping of the lymphatic nodes.

Figure 4.

Lymph node PET imaging of 89Zr-Df-MCLs. (A) In vivo lymph node imaging with PET upon footpad injection of 89Zr-Df-MCLs at different time points. (B) Quantification of 89Zr-Df-MCLs uptake by the mouse footpad and lymph nodes at various time points. (C) In vivo and Ex vivo quantification of 89Zr-Df-MCLs uptake by the mouse footpad and lymph nodes at 24 h time point after footpad injection. (D) Ex vivo PET imaging of lymph nodes and mouse at 24 h p.i.

In conclusion, we have developed a novel cell membrane reassembling method to construct multicompartment membrane-derived liposomes by fusing cancer cell membrane nanovesicles with Tween-80 nanomicelles. After conjugation with p-SCN-deferoxamine via the amino groups of proteins on the surface of MCLs, 89Zr labeled Df-MCLs demonstrated excellent radiochemical stability in different biological media and in vivo. Systematic non-invasive tracking and quantitative investigation of 89Zr-Df-MCLs in vivo was performed to demonstrate rapid clearance of 89Zr-Df-MCLs, eventually estimated to be over 63 %ID at 72 h p.i. through hepatobiliary excretion. Intensive toxicity evaluation confirmed that MCLs did not impose acute or chronic toxicity to the test subjects over extended periods. Importantly, 89Zr-Df-MCLs demonstrated enhanced and persistent uptake in 4T1 tumors, highlighting their capacity as targeted drug delivery platforms. When loaded with tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (TCPP), a model photodynamic agent, the MCLs demonstrated enhanced and irreversible tumor destruction when irradiated focally by a 660 nm laser. In addition, sensitive mapping of deep-seated lymph nodes mapping after local injection revealed the excellent multifaceted potential of biomimetic 89Zr-Df-MCLs to serve as a PET image-guided, cancer-targeting nanoplatform for enhanced outcomes in cancer theranostics in the near future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81601605, 21571147) and the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (2016M600670). This work was also supported by the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the National Institutes of Health (NIBIB/NCI 1R01CA169365, 1R01CA205101, 1R01EB021336, and P30CA014520), and the American Cancer Society (125246-RSG-13-099-01-CCE). This work was also partly supported by the Natural Science Foundation of SZU (827-000143), Shenzhen Peacock Plan (KQTD2016053112051497), and Shenzhen Basic Research Program (JCYJ20170302151858466).

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Dr. Bo Yu, National-Regional Key Technology Engineering Laboratory for Medical Ultrasound, Guangdong Key Laboratory for Biomedical Measurements and Ultrasound Imaging, School of Biomedical Engineering, Health Science Center, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518060, China. Departments of Radiology and Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53705, USA. Key Laboratory for Green Chemical Process of Ministry of Education, School of Chemical Engineering and Pharmacy, Wuhan Institute of Technology, Wuhan 430205, China.

Dr. Shreya Goel, Departments of Radiology and Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53705, USA.

Dr. Dalong Ni, Departments of Radiology and Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53705, USA

Dr. Paul A. Ellison, Departments of Radiology and Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53705, USA

Dr. Cerise M. Siamof, Departments of Radiology and Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53705, USA

Dr. Dawei Jiang, Departments of Radiology and Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53705, USA

Prof. Liang Cheng, Institute of Functional Nano & Soft Materials (FUNSOM), Collaborative Innovation Center of Suzhou Nano Science and Technology, Soochow University, Suzhou 215123, China

Dr. Lei Kang, Departments of Radiology and Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53705, USA. Department of Nuclear Medicine, Peking University First Hospital Beijing, Beijing 100000, China

Prof. Faquan Yu, Key Laboratory for Green Chemical Process of Ministry of Education, School of Chemical Engineering and Pharmacy, Wuhan Institute of Technology, Wuhan 430205, China

Prof. Zhuang Liu, Institute of Functional Nano & Soft Materials (FUNSOM), Collaborative Innovation Center of Suzhou Nano Science and Technology, Soochow University, Suzhou 215123, China

Prof. Todd E. Barnhart, Departments of Radiology and Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53705, USA

Prof. Qianjun He, National-Regional Key Technology Engineering Laboratory for Medical Ultrasound, Guangdong Key Laboratory for Biomedical Measurements and Ultrasound Imaging, School of Biomedical Engineering, Health Science Center, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518060, China

Prof. Han Zhang, Shenzhen Engineering Laboratory of Phosphorene and Optoelectronics, Key Laboratory of Optoelectronic Devices and Systems of Ministry of Education and Guangdong Province, College of Optoelectronic Engineering, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518060, P.R. China

Prof. Weibo Cai, Departments of Radiology and Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53705, USA. University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53705, USA

References

- 1.Salvati A, Pitek AS, Monopoli MP, Prapainop K, Bombelli FB, Hristov DR, Kelly PM, Aberg C, Mahon E, Dawson KA. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8:137. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu Q, Sun W, Lu Y, Bomba HN, Ye Y, Jiang T, Isaacson AJ, Gu Z. Nano Lett. 2016;16:1118. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao L, Bu LL, Xu JH, Cai B, Yu GT, Yu XL, He ZB, Huang QQ, Li A, Guo SS, Zhang WF, Liu W, Sun ZJ, Wang H, Wang TH, Zhao XZ. Small. 2015;11:6225. doi: 10.1002/smll.201502388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sapsford KE, Algar WR, Berti L, Gemmill KB, Casey BJ, Oh E, Stewart MH, Medintz IL. Chem Rev. 2013;113:1904. doi: 10.1021/cr300143v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen GY, Roy I, Yang CH, Prasad PN. Chem Rev. 2016;116:2826. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dehaini D, Wei XL, Fang RH, Masson S, Angsantikul P, Luk BT, Zhang Y, Ying M, Jiang Y, Kroll AV, Gao WW, Zhang LF. Adv Mater. 2017;29 doi: 10.1002/adma.201606209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang RH, Jiang Y, Fang JC, Zhang LF. Biomaterials. 2017;128:69. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao WW, Hu CMJ, Fang RH, Luk BT, Su J, Zhang LF. Adv Mater. 2013;25:3549. doi: 10.1002/adma.201300638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu CMJ, Fang RH, Zhang LF. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2012;1:537. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piao JG, Wang LM, Gao F, You YZ, Xiong YJ, Yang LH. Acs Nano. 2014;8:10414. doi: 10.1021/nn503779d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu JY, Zheng DW, Zhang MK, Yu WY, Qiu WX, Hu JJ, Feng J, Zhang XZ. Nano Lett. 2016;16:5895. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b02786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang RH, Hu CMJ, Luk BT, Gao WW, Copp JA, Tai YY, O’Connor DE, Zhang LF. Nano Lett. 2014;14:2181. doi: 10.1021/nl500618u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deri MA, Ponnala S, Kozlowski P, Burton-Pye BP, Cicek HT, Hu C, Lewis JS, Francesconi LC. Bioconjug Chem. 2015;26:2579. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao L, Bu LL, Xu JH, Cai B, Yu GT, Yu X, He Z, Huang Q, Li A, Guo SS, Zhang WF, Liu W, Sun ZJ, Wang H, Wang TH, Zhao XZ. Small. 2015;11:6225. doi: 10.1002/smll.201502388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu JY, Zheng DW, Zhang MK, Yu WY, Qiu WX, Hu JJ, Feng J, Zhang XZ. Nano Lett. 2016;16:5895. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b02786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parodi A, Quattrocchi N, van de Ven AL, Chiappini C, Evangelopoulos M, Martinez JO, Brown BS, Khaled SZ, Yazdi IK, Vittoria Enzo M, Isenhart L, Ferrari M, Tasciotti E. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8:61. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu CMJ, Zhang L, Aryal S, Cheung C, Fang RH, Zhang LF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106634108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:941. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo HM, Hernandez R, Hong H, Graves SA, Yang YN, England CG, Theuer CP, Nickles RJ, Cai WB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:12806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509667112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi SX, Xu C, Yang K, Goel S, Valdovinos HF, Luo HM, Ehlerding EB, England CG, Cheng L, Chen F, Nickles RJ, Liu Z, Cai WB. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2017;56:2889. doi: 10.1002/anie.201610649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang YM, Jeon M, Rich LJ, Hong H, Geng JM, Zhang Y, Shi SX, Barnhart TE, Alexandridis P, Huizinga JD, Seshadri M, Cai WB, Kim C, Lovell JF. Nat Nanotechnol. 2014;9:631. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ha E, Wang W, Wang YJ. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91:2252. doi: 10.1002/jps.10216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Q, Wang AF, Meng Y, Ning TT, Yang HX, Ding LX, Xiao XY, Li XD. Anal Chem. 2015;87:9810. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaur G, Mehta SK. Int J Pharm. 2017;529:134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandya DN, Bhatt N, Yuan H, Day CS, Ehrmann BM, Wright M, Bierbach U, Wadas TJ. Chem Sci. 2017;8:2309. doi: 10.1039/c6sc04128k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deri MA, Ponnala S, Zeglis BM, Pohl G, Dannenberg JJ, Lewis JS, Francesconi LC. J Med Chem. 2014;57:4849. doi: 10.1021/jm500389b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen F, Goel S, Valdovinos HF, Luo HM, Hernandez R, Barnhart TE, Cai WB. Acs Nano. 2015;9:7950. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b00526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen DQ, Yang DZ, Dougherty CA, Lu WF, Wu HW, He XR, Cai T, Van Dort ME, Ross BD, Hong H. Acs Nano. 2017;11:4315. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b01530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maurer T, Eiber M, Schwaiger M, Gschwend JE. Nat Rev Urol. 2016;13:226. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2016.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deri MA, Ponnala S, Kozowski P, Burton-Pye BP, Cicek HT, Hu CH, Lewis JS, Francesconi LC. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015;26:2579. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.England CG, Kamkaew A, Im HJ, Valdovinos HF, Sun HY, Hernandez R, Cho SY, Dunphy EJ, Lee DS, Barnhart TE, Cai WB. Mol Pharm. 2016;13:1958. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernandez R, Sun H, England CG, Valdovinos HF, Barnhart TE, Yang Y, Cai W. Mol Pharm. 2016;13:2563. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goins B, Phillips WT, Klipper R. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng L, Kamkaew A, Sun HY, Jiang DW, Valdovinos HF, Gong H, England CG, Goel S, Barnhart TE, Cai WB. Acs Nano. 2016;10:7721. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b03074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noguti J, De Moura CFG, De Jesus GPP, Da Silva VHP, Hossaka TA, Oshima CTF, Ribeiro DA. Cancer Genom Proteo. 2012;9:329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng L, Kamkaew A, Shen S, Valdovinos HF, Sun HY, Hernandez R, Goel S, Liu T, Thompson CR, Barnhart TE, Liu Z, Cai WB. Small. 2016;12:5750. doi: 10.1002/smll.201601696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gumus M, Gumus H, Jones SE, Jones PA, Sever AR, Weeks J. Breast Care. 2013;8:199. doi: 10.1159/000352092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu XF, Lin QZ, Chen G, Lu JP, Zeng Y, Chen X, Yan J. Plos One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.