Abstract

It has been known for decades that degeneration of the locus coeruleus (LC), the major noradrenergic nucleus in the brain, occurs in both Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD), but it was given scant attention. It is now recognized that hyperphosphorylated tau in the LC is the first detectable AD-like neuropathology in the human brain, α-synuclein inclusions in the LC represent an early step in PD, and experimental LC lesions exacerbate neuropathology and cognitive/behavioral deficits in animal models. The purpose of this review is to consider the causes and consequences of LC pathology, dysfunction, and degeneration, as well as their implications for early detection and treatment.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, locus coeruleus, alpha-synuclein, tau

Locus Coeruleus Degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease

Alzheimer disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) are the two most prevalent neurodegenerative diseases. While their primary symptoms are distinct (memory loss in AD, motor symptoms in PD), both are characterized by protein aggregates (β-amyloid plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles in AD, α-synuclein Lewy bodies in PD), and they share co-morbid symptoms such as depression, anxiety, sleep abnormalities, and cognitive impairment. An underappreciated hallmark of both diseases is the degeneration of the brainstem locus coeruleus (LC), the major norepinephrine (NE)-producing nucleus in the brain [1–5]. Given the importance of the LC for the regulation of attention, arousal, and mood [6, 7], a potential role for LC degeneration has been suggested for certain neuropsychiatric abnormalities that are common in both AD and PD, such as anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders [8–11].

LC cell loss was first described in AD and PD more than 30 years ago [12, 13]. Although nearly ubiquitous and profound (~50–80%), it was largely ignored in favor of other neurotransmitter systems/nuclei, even though the extent of LC/NE degeneration surpasses even nucleus basalis/acetylcholine loss in AD and dopamine (DA)/substantia nigra loss in PD [14]. The neurodegeneration field has recently taken notice of the LC for two reasons. First, we and others have shown that LC lesions exacerbate AD- and PD-like neuropathology and cognitive/behavioral deficits in animal models [1, 15–22]. Second, evidence from postmortem studies indicates that some of the primary AD (tau) and PD (α-synuclein) pathologies appear very early in the LC. For example, hyperphosphorylated tau, a “pretangle” form of the protein that is prone to aggregation, can be detected in the LC before anywhere else in the brain, sometimes during the first few decades of life [5, 23–28]. Likewise, α-synuclein pathology appears in LC neurons before infiltrating the substantia nigra pars compacta, the canonical midbrain dopaminergic nucleus that controls motor function [29–32]. These LC pathologies often precede the primary symptoms of each disorder (dementia in AD, motor dysfunction in PD), suggesting that LC loss may contribute to disease initiation, progression, and severity rather than merely representing collateral damage in a dying brain [33]. Importantly, normal aging does not affect the LC, indicating that the degeneration is directly related to disease progression [34]. Although it is not yet clear exactly why noradrenergic neuropathology, dysfunction, and degeneration is initiated so early in AD and PD compared to other nuclei, LC neurons have several anatomical, morphological, and neurochemical characteristics that likely contribute to their vulnerability (Box 1).

Box 1. Vulnerability of Locus Coeruleus Neurons.

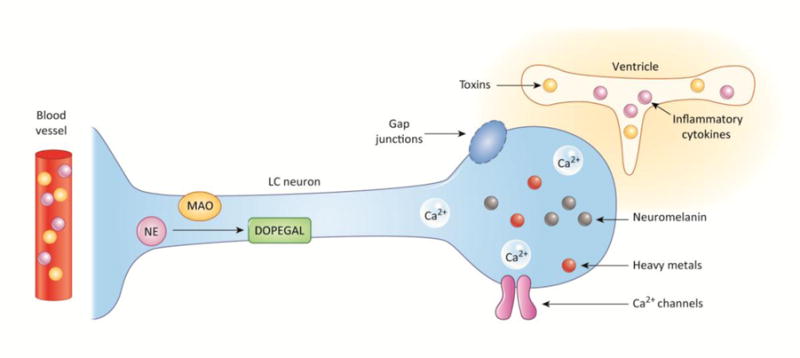

The LC is the site of early pathology and eventually degenerates in AD and PD. There are several reasons that LC neurons might be particularly vulnerable (Figure I) [131].

Neurochemistry

NE, the primary neurotransmitter of LC neurons, is itself a risk factor. NE is normally sequestered inside synaptic vesicles by the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), but after synaptic release, it is taken up into the cytoplasm by the NE transporter (NET). Cytoplasmic NE can autoxidize or be converted to chemically reactive and toxic metabolites (e.g. 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycolaldehyde; DOPEGAL) by monoamine oxidase (MAO), which can then cause damage to proteins, lipids, and nucleotides [97]. LC hyperactivity, which may occur prior to degeneration in AD and PD as proposed in this review, would increase NE turnover and thus DOPEGAL production, leading to further cellular stress.

LC neurons also synthesize neuromelanin, a granular pigment that binds iron and other heavy metals, as well as chemical toxicants and even α-synuclein. Neuromelanin may initially protect LC neurons by chelating damaging agents, but eventually aggravate neurodegeneration by releasing the toxins later in life [132]. It is worth noting that human LC neurons contain neuromelanin, while all other non-primate animals examined (including rodents, which are most commonly used as model organisms to study AD and PD) do not, and humans are the only species that develop sporadic AD and PD.

Physiology

LC neurons display nearly constant “pacemaker” activity that is increased by stress, with acute phasic bursting patterns in response to salient sensory stimuli superimposed on the tonic firing [133]. Thus, the bioenergetic needs of these cells are high and rely on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, which can produce significant levels of oxidative stress over time. Pacemaker activity is maintained by Ca2+ channels, and Ca2+ that enters the cell can be shuttled to mitochondria, further promoting oxidative stress. The potential for LC hyperactivity in early stage disease would exacerbate Ca2+ influx and mitochondrial toxicity. Interestingly, mitochondrial stress is elevated in the LC neurons of mice lacking DJ-1, a protein implicated in heritable early onset forms of PD [134].

LC neurons are also electrically coupled via gap junctions, which drives their synchronous firing [135–137]. Thus, dysregulated hyperactivity of a subset of LC neurons (e.g. by chronic stress, a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease) may spread throughout the nucleus, increasing oxidative stress.

Neuroanatomy

LC cell bodies are located in the dorsal pons just below the fourth ventricle [133]. Their proximity to the ventricle affords liberal access to the cerebrospinal fluid, which is a potential source of chemical toxicants and neuroinflammatory molecules. The LC also densely innervates brain capillaries, and thus can take up toxicants from the blood, even those present at low levels with poor blood-brain barrier permeability [132]. Many LC axons are thin, highly arborized, unmyelinated, and among the longest in the brain, potentially making them particularly fragile [133] (although conduction velocity evidence suggests existence of some myelinated LC axons in nonhuman primates) [138]. Finally, the observation that in experimental preparations gap junctions can transfer dye between LC neurons suggests that toxic chemicals in one cell could “infect” its neighbors.

Despite this renewed interest in the LC, much remains to be investigated. In this review, I will discuss how aberrant tau and α-synuclein lead to the dysfunction and degeneration of the LC, whether the LC can seed the spread of protein aggregates to other regions of the brain, and the dynamic cognitive/behavioral consequences of LC changes throughout the course of disease.

Effects of Pathogenic Tau and α-Synuclein on Locus Coeruleus Survival

It is now recognized that tau and α-synuclein pathology occur in the LC relatively early in AD and PD, respectively. According to the classic Braak AD staging paradigm, hyperphosphorylated, or “pretangle” forms of tau first appear in the transentorhinal cortex (Stages I–II), followed by the entorhinal cortex, hippocampus, and related temporal lobe structures (Stages III–IV), and finally cortical regions in severe AD (Stages V–VI) [35]. However, brainstem involvement was not assessed in those studies. In 2011, Braak and colleagues reported that AT8-positive hyperphosphorylated tau immunostaining can be detected in the LC prior to any other structure in the brain, occasionally as early as the first few decades of life, necessitating an amendment of their staging criteria to include a “Stage 0 (a-b)” consisting of LC-specific tau pathology [23, 24, 26]. Several groups have since confirmed and extended these findings [25, 36]. While it is well established that catastrophic loss of LC neurons occurs in late AD, and pathogenic forms of tau are certainly neurotoxic and capable of killing neurons, an emerging facet of the story is the relationship (or lack thereof) between early tau pathology in the LC and the eventual demise of these cells. Notably, aberrant forms of tau appear in the LC years, or even decades, prior to frank cell body degeneration, and some studies have failed to observe correlations between tangle density and neuronal loss [37]. Some information now exists regarding the exact timing of LC cell loss. Using neuropathological staging, Grinberg and colleagues showed that while tau pathology is evident in the LC at Braak Stage 0, the number of LC neurons does not significantly decline until mid-disease (Braak Stage III) [34], while Kelly et al employed cognitive criteria and reported 25–30% loss starting in mild cognitive impairment (MCI, a putative prodromal phase of AD), with 7/10 of the MCI subjects diagnosed at Braak Stage III/IV [38]. Another recent paper observed 13% fewer LC neurons in MCI corresponding to Braak Stage I/II [39]. Nevertheless, postmortem human studies indicate that LC neurons can withstand harboring pathological tau for surprisingly long periods of time before succumbing to cell death, and animal and cellular models appear to support this idea. For example, transgenic mice overexpressing a mutant form of human tau prone to hyperphosphorylation and aggregation (P301S) under control of the pan-neuronal prion promoter develop AD-like tau pathology that kills forebrain, but not LC neurons by the time the mice die at ~12 months [40, 41], and primary LC cultures made from neonatal P301S mice have normal survival rates [42]. Likewise, we recently showed that in TgF344-AD transgenic rats, which overexpress mutant human amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1, hyperphosphorylated tau appears in the LC months prior to anywhere else in the brain (similar to humans), yet no detectable LC cell death is evident nearly a year later [42]. These and complementary findings motivated some authors to propose a “two-hit” hypothesis, positing that in addition to aberrant tau, a second trigger is necessary to induce LC neuron death [34]. There is one animal study that reported rapid tau neurotoxicity in the LC, but the result should be interpreted with caution because it employed a strategy whereby pre-formed toxic fibrils were injected directly into the LC of P301S transgenic mice [43]. Thus, the mechanisms and progression of neuronal death may be distinct from those associated with endogenously produced forms of aberrant tau in the absence of overexpressed mutant tau.

Similar, albeit less comprehensive, results exist for PD. Braak staging of α-synuclein pathology revealed early involvement the LC (Stage 2), prior to deposition in the dopaminergic substantia nigra (Stage 3) [32], and catastrophic LC cell loss is evident later in disease [1, 14, 44]. A causal role of α-synuclein is supported by the loss of LC neurons in patients with familial α-synuclein mutations [45], although these patients were symptomatic and the post-mortem analysis was done many years after symptom onset. Unfortunately, no rigorous studies evaluating LC neuron number through progressive α-synuclein/PD stages akin to those described above for tau/AD have been conducted, but it does appear that LC neurons can survive for years following α-synuclein aggregation. Animal models have yielded similar results; transgenic mice overexpressing the disease-causing A53T mutant form of human α-synuclein under control of the mouse Prnp promoter exhibit increased α-synuclein immunostaining in LC cell bodies but no cell death up to 15 months of age [46]. Again consistent with the “two-hit” hypothesis, mice overexpressing wild-type or mutant α-synuclein do not display substantia nigra DA neuron degeneration unless DA levels are artificially elevated [47]. For both AD and PD, it is also important to consider that the exact toxic conformations of tau and α-synuclein are still under debate. Some data suggest that soluble tau and α-synuclein oligomers are the more toxic species, while aggregation into insoluble inclusions may be a protective mechanism [48, 49]. If this were the case, rapid aggregation of the more toxic soluble forms of these proteins could delay frank LC degeneration.

Effects of Pathogenic Tau and α-Synuclein on Locus Coeruleus Morphology and Neurochemistry

Although LC neurons show resilience to frank cell death despite chronic exposure to aberrant forms of tau and α-synuclein in AD and PD, respectively, pathological changes in cell morphology are evident. For example, early in AD, LC neurons display swollen cell bodies and contracted dendrites [11]. Indeed, total LC volume decreases ~8% per Braak Stage starting at Stage 0, reaching ~25% before LC neuronal loss is detected and likely reflecting degeneration of proximal axons and dendrites [34]. A consistent finding in both diseases is the loss of noradrenergic axons, terminals, and NE in LC projection regions. Reductions in noradrenergic fibers, NE levels, and DBH activity in forebrain LC projection regions are evident early in disease progression, also indicative of a “dying back” phenotype [50–53]. Studies in animal and cell models support this idea. In TgF344-AD rats, hippocampal NE levels and fiber density are diminished, and LC tau pathology is negatively correlated with noradrenergic innervation of the entorhinal cortex [42], suggesting a causal relationship. Interestingly, LC fibers are relatively spared in some brain regions (e.g. prefrontal cortex) compared to others (e.g. dentate gyrus) in TgF344-AD animals, suggesting an interaction between intracellular tau and the extracellular microenvironment. Similar loss of forebrain NE was observed in SHR72 rats overexpressing a pathogenic truncated form of human tau [54]. Moreover, cultured LC neurons from P301S mice have normal cell viability but shorter neurites, and 10-month old P301S animals have a significant reduction of NE in the hippocampus compared to wild-type littermates, again implicating a direct effect of aberrant tau [41, 42]. Combined, these observations indicate that although tau-riddled LC neurons can survive for long periods of time, their capacity for optimal noradrenergic neurotransmission is impaired [26]. Moreover, tau pathology may trigger changes in LC gene expression that either contribute to degeneration or represent compensatory protective mechanisms (Box 2).

Box 2. Locus Coeruleus Gene Expression in AD and PD.

Given that tau and α-synuclein pathology persist in LC neurons for long periods of time, it is reasonable to assume that dysfunction and degeneration of LC neurons involves long-term changes in the transcripome and proteome of these cells. Despite the technical and analytical challenges, several studies have begun to assess alterations in gene expression in LC neurons from postmortem AD and PD subjects. The most elegant and comprehensive study compared microarray profiles of single LC neurons from subjects with no cognitive impairment (NCI), MCI, and mild/moderate AD [38]. In MCI and AD, the authors found: (1) reduction in genes associated with mitochondrial function (e.g. the Nrf1 transcription factor that drives expression of several classes of mitochondrial genes and the Cytc1 component of the respiratory chain); (2) reduction in genes associated with neural plasticity (e.g. the axon maintenance molecule Nfh and the microtubule stabilizing protein Map1b); and (3) increases in genes encoding cytoskeletal proteases. There was also a 25% increase in the ratio of 3-repeat tau to 4-repeat tau, which is associated with tangle formation and slower axonal transport. These results suggest that LC neurons are under considerable respiratory and oxidative stress, and are undergoing axonal degeneration prior to MCI and Braak Stage III, when these cells are just starting to die. Importantly, downregulated metabolic and plasticity genes were significantly correlated with decreased cognitive performance and increased neuropathological burden in LC projection areas. Other groups using expression microarrays and one employing a proteomic approach have observed increases in protein folding and chaperone pathways in AD [27], as well as alterations in gene/protein networks related to mitochondrial function, protein misfolding, oxidative stress, cytoskeletal structure, neuronal growth, synaptic transmission, inflammatory response, and immune signaling in PD [139–141]. These latter studies should be interpreted with caution because the samples were derived from homogenized tissue and thus were comprised of other types of neurons and glia in addition to bona fide noradrenergic LC cells, and there is no evidence for a causal relationship between tau or α-synuclein and the changes per se. Finally, it remains to be experimentally determined whether the patterns of gene up- and down-regulation represent the drivers of pathological dysfunction and cell death, or alternatively – compensatory protective responses. In sum, the field has barely scratched the surface of identifying transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic alterations associated with aberrant tau and α-synuclein in the LC – an important goal for future studies.

Forebrain NE depletion, as well as morphological changes in noradrenergic fibers, synapses, and mitochondria, have been consistently observed in PD [1, 10, 55, 56], and despite no LC cell death in A53T α-synuclein transgenic mice, age-dependent loss of NE terminals and tissue levels is evident [46]. This pattern is consistent with dopaminergic degeneration in clinical and experimental PD, where imaging studies reveal DA axon loss prior to cell body degeneration [57], striatal DA loss (~80%) is greater than death of DA neurons in the substantia nigra (~50%) [58], and Thy1-Syn transgenic mice show progressive reduction of striatal DA by 14 months but normal DA neuron number up to 22 months [59]. Gene expression changes may also accompany α-synuclein pathology in the LC (Box 2). In general, the more pronounced vulnerability of LC fibers compared to cell bodies in AD and PD may be a consequence of protein localization; as a microtubule binding protein, tau is concentrated in axons and terminals, while α-synuclein is involved in vesicular fusion and found preferentially at synapses.

Effects of Pathogenic Tau and α-Synuclein on Locus Coeruleus Function: Degeneration in Later-Stage Disease

Because the LC degenerates in AD and PD, NE levels also decline in both diseases [1, 2, 8]. Several brain structures implicated in learning and memory, including the hippocampus and multiple cortical regions, receive dense projections from the LC, and this reduction in noradrenergic transmission is consistent with the cognitive impairment evident in AD and PD [7, 30, 31, 60–62]. Indeed, neurotoxic lesions of the LC or genetic NE depletion exacerbate learning and memory deficits in several rodent models of AD and PD [16–18, 20, 21, 63], and we and others have recently extended this finding to clinical populations and tau-based models [38, 41]. Severity of dementia is strongly correlated with loss of NE neurons in AD [64–66], while LC preservation encodes cognitive reserve [67, 68]. Moreover, degeneration of the LC and noradrenergic inputs to the cortex appear to be more severe in PD patients with dementia compared to those without cognitive impairment [31, 69]. Deficits in attention and arousal (e.g. excessive sleepiness) are also common in AD and PD, as would be expected from LC degeneration [70–73], and NE plays an important role in olfactory function, which is impaired in both diseases [29, 74, 75]. Although the motor symptoms of PD are classically attributed to the loss of DA, NE provides critical excitatory drive onto midbrain neurons [76], and NE deficiency can cause dysregulation of DA signaling to the striatum and thus can indirectly impact motor function [1, 15, 77, 78]. Some studies support [22, 79], while others refute [63] a role for LC degeneration in the development and severity of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesias.

Effects of Pathogenic Tau and α-Synuclein on Locus Coeruleus Function: Hyperactivity in Early-Stage Disease?

While the effects of LC degeneration on late-stage disease appear straightforward, it is important to consider that aberrant forms of tau and α-synuclein in the LC are among the earliest signs of AD- and PD-like neuropathology, respectively, and can be detected years or even decades prior to neuronal death. Thus, important questions remain regarding how pathogenic forms of tau and α-synuclein influence LC activity and NE transmission, particularly in light of evidence for noradrenergic hyperactivity early in disease. Anxiety and depression, which are risk factors for developing AD and are common non-motor symptoms in PD [80, 81], are consistent with increased LC activity [82]. For example, optogenetic activation of the LC is anxiogenic [83], and although the classical “Monoamine hypothesis of depression” developed in the 1960’s fingered NE deficiency as a culprit [84, 85], that model has evolved to the more modern interpretation that increased LC activity provokes depression-like behavior; several animal models of depression, as well as postmortem analysis of depressed individuals, show evidence of LC hyperactivity [86–89]. While excessive sleepiness is associated with reduced LC function in both diseases, multiple types of sleep disorders are common, and some patients instead present with insomnia [81]. LC neurons are highly active during wakefulness, fire slowly during non-REM sleep, and are almost completely quiescent during REM sleep. Importantly, changes in LC firing precede sleep-wake transitions, and optogenetic or chemogenetic activation of the LC induces wakefulness, suggesting a causative rather than responsive role [71, 90, 91]. Intriguingly, sleep fragmentation (i.e. reduced duration of uninterrupted sleep bouts) precedes and predicts dementia and Aβ pathology in AD [92], while REM Behavioral Disorder (RBD; loss of muscle atonia and subsequent movement during REM sleep) is among the earliest signs of PD, often manifesting years prior to motor dysfunction [81]. Inappropriate LC firing and subsequent “mini-awakenings” during slow-wave and/or REM sleep is consistent with both sleep fragmentation and RBD. The role of the LC in sleep is complex, and a full discussion about the diverse consequences of LC degeneration on arousal is beyond the scope of this article, but the reader is referred to several excellent reviews on the subject [11, 93, 94].

Some neurochemical evidence also supports LC hyperactivity in neurodegenerative disease. Although decreased brain tissue NE levels are nearly ubiquitous in postmortem AD samples, several studies report elevated CSF NE and/or NE turnover (as assessed by NE:metabolite ratios) in both postmortem samples and living AD patients [51, 52, 95, 96]. CSF levels of NE and its metabolites are reported to be unchanged or decreased in PD [97, 98]; however, the subjects in these studies had full-blown disease and probable frank LC degeneration. Future studies examining LC function/NE levels in people with non-motor symptoms but prior to clinical motor dysfunction may reveal signs of LC hyperactivity in prodromal/early PD. One important factor to consider in the context of LC hyperactivity is the possible emergence of compensatory mechanisms for LC dysfunction/degeneration [8]. For example, one study found that high NE turnover (MHPG:NE ratio) was inversely correlated with the number of surviving LC neurons in AD [96]. Others reported increased expression of tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in NE biosynthesis, in the LC, as well as axonal sprouting in the hippocampus and in AD [99]. Elevated noradrenergic activity in response to LC loss is also supported by animal studies. For example, partial neurotoxin-induced LC lesions increased LC firing in mice [89] and cortical NE turnover in rats [100].

Neurobiological evidence for a relationship between tau/α-synuclein and LC hyperactivity is in its infancy, but is quite intriguing. In other brain regions, overexpression of human tau drives hyperexcitability [101, 102]. Importantly, these changes in excitability were evident early, when tau pathology was quite modest and long before neuronal cell death. Thus, it is not a stretch to think that aberrant tau induces hyperexcitability of LC neurons early in disease. α-synuclein appears to have dual roles in neurotransmitter release, both inhibiting exocytosis and promoting the formation of the vesicular fusion pore [103]. If pathogenic species of the protein found in the LC early in PD confer patients exhibit a loss of exocytosis inhibition but retain fusion pore facilitation, the result could be enhanced NE transmission. Rare PD-causing mutations in α-synuclein (e.g. A30P, A53T) actually have the opposite phenotype; they can still negatively regulate neurotransmitter exocytosis but no longer promote fusion pore dilation, arguing against this mechanism for explaining increased NE transmission. On the other hand, extracellular DA is increased in young mice (~6 months) that overexpress wild-type human α-synuclein, prior to the reduction in tissue DA content that occurs later (~14 months), several lines of α-synuclein transgenic mice show behavioral hyperactivity consistent with increased DA transmission early in life before being replaced by frank degeneration and motor deficits over time, and in vivo imaging of asymptomatic people carrying LRRK2 mutations that increase risk for PD revealed increased DA turnover [104]. Future experiments designed to determine how pathogenic forms of tau and α-synuclein impact LC firing and NE release will be critical for testing the hypothesis that LC hyperactivity contributes to early phenotypes in AD and PD.

Seeding and Propagation of Tau and α-synuclein Pathology From the LC

The progression of AD and PD pathology follows a remarkably systematic pattern across individuals, and aberrant forms of many neurodegenerative disease-associated proteins, including tau and α-synuclein, are capable of neuron-to-neuron propagation. The “seeding” hypothesis refers to the idea that misfolded proteins originate in one population of neurons, and then spread pathology to interconnected brain regions via a prion-like process of corruptive templating [105]. Because hyperphosphorylated tau can first be detected in the LC, and the LC sends dense projections to other vulnerable brain regions that display early tau pathology (e.g. the transentorhinal cortex), it has been suggested that the LC might be one of the origins (perhaps along with other affected brainstem nuclei that project to the trans-entorhinal cortex such as the dorsal raphe), of tau neuropathology in AD [26, 36, 106, 107]. An important point to consider is that neuronal hyperactivity can accelerate the spread of tau seeds [4, 108]. Thus, early pathology in the LC could initiate a vicious cycle in which aberrant tau induces LC hyperactivity, thereby promoting its own spread to interconnected brain regions and facilitating the progression of disease. Although α-synuclein pathology can be detected elsewhere in the body (e.g. dorsal motor nucleus, vagus nerve, and perhaps even the gut) prior to its appearance in the LC, the connectivity between the LC and other brain regions affected in PD suggests that it may be a major source of α-synuclein seeds early in the disease [32]. One study found that α-synuclein pathology rapidly appears in the LC following viral vector-mediated α-synuclein expression in the vagus nerve of rats [109], suggesting that the LC may act as a “way station” of pathological α-synuclein transmission from the periphery to the rest of the brain, but others have argued against this idea [110]. While the ability of several brain regions to seed and propagate tau and α-synuclein pathology has been demonstrated in animal models of disease, only a single study has directly tested spread from the LC. Specifically, Iba and colleagues described the propagation of tau pathology from the LC to some brain regions such as the frontal cortex that become affected in late-stage AD [43]. However, because brain regions affected in early AD (e.g. entorhinal cortex, hippocampus) were devoid of tau pathology, the authors concluded that the LC is probably not the origin (at least not the sole origin) of tau pathology, although they acknowledged some limitations of their experimental design. For example, they used preformed synthetic tau fibrils rather than inducing endogenous tau expression in LC neurons. LC-derived tau goes through several stages of hyperphosphorylation and misfolding prior to aggregation in AD, and these forms may have different seeding/propagation properties than preformed fibrils. In addition, they used mice overexpressing mutant human tau, and the artificial pattern of transgene expression may bias vulnerability to developing fibril-mediated tau pathology in a way that does not reflect physiological AD.

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

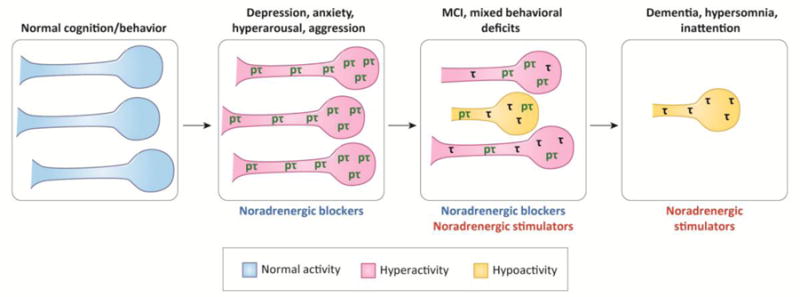

Tau and α-synuclein in the LC are among the earliest detectable AD- and PD-like pathologies in the human brain, and are associated with neuronal dysfunction, death, cognitive/behavioral phenotypes, and the spread of pathology. A framework for considering LC deficits in AD and PD is presented in Figure 1. At the very earliest “prodromal” stage, various insults (e.g. inflammation, oxidative stress, heavy metal accumulation, etc; see Box 1) trigger production of aberrant forms of tau and α-synuclein, leading to LC hyperactivity and associated phenotypes such as hyperarousal, anxiety, and depression. During the initial stages of clinical disease, more advanced toxic tau begin causing terminal/fiber degeneration, resulting in “mixed” phenotypes that correspond with various combinations of LC hyperactivity (see above) and NE deficiency (e.g. MCI). In full-blown disease, bona fide neurofibrillary tangles (AD) and Lewy bodies (PD) are evident, with decimation of LC terminal/fibers, frank cell body degeneration, and dementia. The phenotypic progression likely differs between individuals (depending on the exact time course of pathology, degeneration, and compensation) and between diseases.

Figure 1. Overview of locus coeruleus function in AD and PD.

The schematic outlines a hypothetical model of LC neurons’ pathology, activity, morphology, and survival along disease progression. Corresponding cognitive and behavioral phenotypes are listed above each stage, while potential therapies are listed below. The figure refers to the progression of AD (see next), whereas a similar process is hypothesized for PD, with the difference that α-synuclein/Lewy body pathology occurs instead of tau/neurofibrillary tangles. The absence of disease is associated with normal LC activity, coupled with normal cognition and behavior. In the earliest prodromal stages of AD, hyperphosphorylated “pretangle” forms of tau (pτ) appear in the LC and cause neuronal hyperactivity and corresponding behavioral phenotypes. At this stage, therapies that attenuate NE transmission could counteract the hyperactivity. As the pretangle tau begins to aggregate and progresses to more advanced forms (e.g. neurofibrillary tangles; τ), LC fibers and terminals begin to degenerate, resulting in dysregulated LC activity, mixed behavioral phenotypes, and mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Therapies that either decrease or increase NE transmission might be applicable, depending on the specific manifestation of symptoms in a given individual. In late-stage disease, frank LC degeneration occurs. Severe deficits in cognition and arousal could possibly be treated with therapies that increase NE transmission.

Although this review has focused on the similarities between LC degeneration in AD and PD, it is important to acknowledge the differences as well. For example, the rostral LC is particularly prone to degeneration in AD, while the entire LC appears equally vulnerable in PD [30, 34, 44, 69], although these data are based on a relatively small sample size and should be interpreted with caution. In addition, alterations in the expression of genes regulating NE synthesis and transmission are distinct between the two diseases [111]. While some available data is consistent with the model described above, many of the key concepts have not been tested directly (see Outstanding Questions), and will require the generation of new cell and animal models that express different forms of tau and α-synuclein exclusively in LC neurons to definitely assign causal relationships.

While most work on the LC in the context of neurodegeneration has been in relation to AD and PD, there is evidence to suggest that LC pathology and degeneration occur in others neurodegenerative diseases. For example, Lewy bodies and cell loss are featured in the LC of dementia with Lewy bodies [99, 112, 113], and LC-localized tau is observed in progressive supranuclear palsy [114], corticobasal degeneration [114], and the Pick’s disease variant of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) [115] that features both Lewy bodies and tau inclusions in a subset of LC neurons [116]. Meticulous stage-dependent characterization of LC pathology in other neurodegenerative diseases and association with symptom onset and progression are sorely needed to assess the potential involvement of the noradrenergic system.

The impact of LC hyperactivity and degeneration likely extends beyond alterations in noradrenergic function. Besides NE, LC neurons produce a host of other small molecule and peptide neuromodulators including adenosine triphosphate (ATP) [114], galanin [117, 118], neuropeptide Y (NPY) [117], enkephalin [119], cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) [120], and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [121, 122]. Galanin and BDNF are of particular interest because they have neurotrophic properties and have been directly implicated in neurodegenerative disease [123–126]. Thus, although LC neurons are generally classified as “noradrenergic”, the disruption of multiple neuromodulator signaling pathways may underlie the consequences of altered LC activity and function in AD and PD.

It is important to consider the clinical implications of this proposed model for LC-based therapeutics. At the earliest stage of disease progression, the most effective interventions might be those that address the initial vulnerability of LC neurons, and thereby preempt the development of dysfunction and eventual demise (e.g. Ca2+ channel antagonists, growth/survival factors, antioxidants, anti-inflammatory molecules). This approach will also require new diagnostic tools, such as combining recent techniques for in vivo imaging of LC neurons and tau or α-synuclein [68, 127, 128]. In addition, treatments that dampen LC hyperactivity/excessive NE transmission (adrenergic receptor antagonists, or chemogenetic/optogenetic silencing – if these become clinically-relevant in the future) and potentially retard the spread of pathology from the LC would be warranted [95, 129]. After the development of brain-wide pathology and the onset of cognitive impairment, therapies that increase NE transmission (e.g. chemogenetic/optogenetic facilitation, NE prodrugs/agonists/reuptake inhibitors, aerobic exercise, environmental enrichment, etc) could be of benefit, as already shown for animal models and in some human studies [16, 17, 21, 30, 42, 130, 131]. Drugs that act on LC co-transmitters that are dysergulated should not be discounted; for example, since galanin has neuroprotective properties and suppresses LC activity [118], the galaninergic system is an appealing target for early AD. Importantly, because LC neurons can survive for decades with AD or PD pathology, a long window of opportunity exists for LC-based therapeutics, even when noradrenergic fibers and transmission are already compromised [4, 42].

Figure I. Factors contributing to locus coeruleus vulnerability.

Shown is a representation of the multiple properties of LC neurons that may make them vulnerable to degeneration. These include: (1) location (cell bodies apposed to the ventricle, and fibers terminating at blood vessels that expose them to potential toxins and inflammatory cytokines); (2) morphology (cell bodies connected by gap junctions through which toxic compounds can spread, as well as long, thin axons that are susceptible to damage); and (3) molecular/chemical composition (neuromelanin that accumulates heavy metals, NE conversion to toxic metabolites, and high levels of intracellular Ca2+ that promote oxidative stress).

Outstanding Questions Box.

Why are LC neurons uniquely vulnerable to developing tau and α-synuclein pathology relatively early in life?

What makes LC neurons resilient to tau- and α-synuclein-induced cell death?

Do aberrant forms of tau and α-synuclein cause LC hyperactivity, fiber degeneration, and neuronal death, and if so, which forms?

Are some of the molecular alterations in LC neurons during degeneration compensatory mechanisms that promote survival in response to abnormal tau and α-synuclein? If so, which of these alterations are pathogenic, thereby contributing to degenerative processes?

What makes some LC fibers more vulnerable than others, and are these differences intrinsic, or could they be explained by the distinct microenvironments found in projection regions?

Why are different parts of the LC more vulnerable in AD vs. PD, and why do LC neurons have some distinct responses in the two diseases?

Can tau and α-synuclein pathology spread from the LC to interconnected brain regions, and what regulates this process?

Can LC/tau/α-synuclein imaging be used as a tool for early diagnosis and tracking disease progression?

Which AD and PD-associated phenotypes can be attributed to LC dysfunction? Are these phenotypes amenable to LC/NE-based therapeutics?

What role, if any, does disruption of LC co-transmitters (e.g. galanin, BDNF) play in disease, and are these systems viable medicinal targets?

Highlights.

A unique combination of neuroanatomy, neurochemistry, and physiology render LC neurons vulnerable to insults and degeneration.

The LC is among the earliest sites of detectable pathology in AD (tau) and PD (α-synuclein), and may seed the development of aberrant protein aggregates in interconnected brain regions.

In both AD and PD, LC neurons display dysfunction, fiber degeneration, and cell death.

LC dysfunction and degeneration likely contributes to neuropsychiatric, neurological, and cognitive symptoms in AD and PD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Aging (AG047667).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rommelfanger KS, Weinshenker D. Norepinephrine: The redheaded stepchild of Parkinson’s disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinshenker D. Functional consequences of locus coeruleus degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5:342–345. doi: 10.2174/156720508784533286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalermpalanupap T, et al. Targeting norepinephrine in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013;5:21. doi: 10.1186/alzrt175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chalermpalanupap T, et al. Down but Not Out: The Consequences of Pretangle Tau in the Locus Coeruleus. Neural Plast. 2017;2017:7829507. doi: 10.1155/2017/7829507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Tredici K, Braak H. Dysfunction of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system and related circuitry in Parkinson’s disease-related dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:774–783. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ressler KJ, Nemeroff CB. Role of norepinephrine in the pathophysiology and treatment of mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1219–1233. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sara SJ. The locus coeruleus and noradrenergic modulation of cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:211–223. doi: 10.1038/nrn2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrmann N, et al. The role of norepinephrine in the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16:261–276. doi: 10.1176/jnp.16.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benarroch EE. Locus coeruleus. Cell Tissue Res. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00441-017-2649-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delaville C, et al. Noradrenaline and Parkinson’s disease. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:31. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Theofilas P, et al. Turning on the Light Within: Subcortical Nuclei of the Isodentritic Core and their Role in Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46:17–34. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mann DM, et al. Changes in the monoamine containing neurones of the human CNS in senile dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136:533–541. doi: 10.1192/bjp.136.6.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mann DM, Yates PO. Pathological basis for neurotransmitter changes in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1983;9:3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1983.tb00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zarow C, et al. Neuronal loss is greater in the locus coeruleus than nucleus basalis and substantia nigra in Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:337–341. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rommelfanger KS, et al. Norepinephrine loss produces more profound motor deficits than MPTP treatment in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13804–13809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702753104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kummer MP, et al. Ear2 deletion causes early memory and learning deficits in APP/PS1 mice. J Neurosci. 2014;34:8845–8854. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4027-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammerschmidt T, et al. Selective loss of noradrenaline exacerbates early cognitive dysfunction and synaptic deficits in APP/PS1 mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jardanhazi-Kurutz D, et al. Induced LC degeneration in APP/PS1 transgenic mice accelerates early cerebral amyloidosis and cognitive deficits. Neurochem Int. 2010;57:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalinin S, et al. Noradrenaline deficiency in brain increases beta-amyloid plaque burden in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1206–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heneka MT, et al. Locus ceruleus degeneration promotes Alzheimer pathogenesis in amyloid precursor protein 23 transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1343–1354. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4236-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalinin S, et al. The noradrenaline precursor L-DOPS reduces pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:1651–1663. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin E, et al. Noradrenaline neuron degeneration contributes to motor impairments and development of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2014;257:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braak H, et al. Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70:960–969. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318232a379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braak H, Del Tredici K. The pathological process underlying Alzheimer’s disease in individuals under thirty. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:171–181. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elobeid A, et al. Hyperphosphorylated tau in young and middle-aged subjects. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:97–104. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0906-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braak H, Del Tredici K. Where, when, and in what form does sporadic Alzheimer’s disease begin? Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25:708–714. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32835a3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andres-Benito P, et al. Locus coeruleus at asymptomatic early and middle Braak stages of neurofibrillary tangle pathology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2017;43:373–392. doi: 10.1111/nan.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grudzien A, et al. Locus coeruleus neurofibrillary degeneration in aging, mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Del Tredici K, et al. Where does parkinson disease pathology begin in the brain? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:413–426. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.5.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vermeiren Y, De Deyn PP. Targeting the norepinephrinergic system in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders: The locus coeruleus story. Neurochem Int. 2017;102:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braak H, Del Tredici K. Neuropathological Staging of Brain Pathology in Sporadic Parkinson’s disease: Separating the Wheat from the Chaff. J Parkinsons Dis. 2017;7:S73–S87. doi: 10.3233/JPD-179001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braak H, et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rub U, et al. The Brainstem Tau Cytoskeletal Pathology of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Brief Historical Overview and Description of its Anatomical Distribution Pattern, Evolutional Features, Pathogenetic and Clinical Relevance. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2016;13:1178–1197. doi: 10.2174/1567205013666160606100509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Theofilas P, et al. Locus coeruleus volume and cell population changes during Alzheimer’s disease progression: A stereological study in human postmortem brains with potential implication for early-stage biomarker discovery. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ehrenberg AJ, et al. Quantifying the accretion of hyperphosphorylated tau in the locus coeruleus and dorsal raphe nucleus: the pathological building blocks of early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2017;43:393–408. doi: 10.1111/nan.12387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Busch C, et al. Spatial, temporal and numeric analysis of Alzheimer changes in the nucleus coeruleus. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:401–406. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelly SC, et al. Locus coeruleus cellular and molecular pathology during the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5:8. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0411-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arendt T, et al. Early neurone loss in Alzheimer’s disease: cortical or subcortical? Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:10. doi: 10.1186/s40478-015-0187-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshiyama Y, et al. Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron. 2007;53:337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chalermpalanupap T, et al. Locus coeruleus ablation exacerbates cognitive deficits, neuropathology, and lethality in P301S tau transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2017 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1483-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rorabaugh JM, et al. Chemogenetic locus coeruleus activation restores reversal learning in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2017;140:3023–3038. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iba M, et al. Tau pathology spread in PS19 tau transgenic mice following locus coeruleus (LC) injections of synthetic tau fibrils is determined by the LC’s afferent and efferent connections. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130:349–362. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1458-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.German DC, et al. Disease-specific patterns of locus coeruleus cell loss. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:667–676. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pasanen P, et al. Novel alpha-synuclein mutation A53E associated with atypical multiple system atrophy and Parkinson’s disease-type pathology. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:2180e2181–2185. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sotiriou E, et al. Selective noradrenergic vulnerability in alpha-synuclein transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:2103–2114. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mor DE, et al. Dopamine induces soluble alpha-synuclein oligomers and nigrostriatal degeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1560–1568. doi: 10.1038/nn.4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cowan CM, Mudher A. Are tau aggregates toxic or protective in tauopathies? Front Neurol. 2013;4:114. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2013.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lashuel HA, et al. The many faces of alpha-synuclein: from structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:38–48. doi: 10.1038/nrn3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marcyniuk B, et al. The topography of cell loss from locus caeruleus in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 1986;76:335–345. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(86)90179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palmer AM, et al. Catecholaminergic neurones assessed ante-mortem in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1987;414:365–375. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palmer AM, et al. Monoaminergic innervation of the frontal and temporal lobes in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1987;401:231–238. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trillo L, et al. Ascending monoaminergic systems alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. translating basic science into clinical care. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:1363–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mravec B, et al. Tauopathy in transgenic (SHR72) rats impairs function of central noradrenergic system and promotes neuroinflammation. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:15. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0482-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fornai F, et al. Noradrenaline in Parkinson’s disease: from disease progression to current therapeutics. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:2330–2334. doi: 10.2174/092986707781745550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Espay AJ, et al. Norepinephrine deficiency in Parkinson’s disease: the case for noradrenergic enhancement. Mov Disord. 2014;29:1710–1719. doi: 10.1002/mds.26048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng HC, et al. Clinical progression in Parkinson disease and the neurobiology of axons. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:715–725. doi: 10.1002/ana.21995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hornykiewicz O. Biochemical aspects of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1998;51:S2–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2_suppl_2.s2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tofaris GK, et al. Pathological changes in dopaminergic nerve cells of the substantia nigra and olfactory bulb in mice transgenic for truncated human alpha-synuclein(1-120): implications for Lewy body disorders. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3942–3950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4965-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hansen N. The Longevity of Hippocampus-Dependent Memory Is Orchestrated by the Locus Coeruleus-Noradrenergic System. Neural Plast. 2017;2017:2727602. doi: 10.1155/2017/2727602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vazey EM, Aston-Jones G. The emerging role of norepinephrine in cognitive dysfunctions of Parkinson’s disease. Front Behav Neurosci. 2012;6:48. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jacobs HI, et al. Relevance of parahippocampal-locus coeruleus connectivity to memory in early dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:618–626. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perez V, et al. Effect of the additional noradrenergic neurodegeneration to 6-OHDA-lesioned rats in levodopa-induced dyskinesias and in cognitive disturbances. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2009;116:1257–1266. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adolfsson R, et al. Changes in the brain catecholamines in patients with dementia of Alzheimer type. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;135:216–223. doi: 10.1192/bjp.135.3.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bondareff W, et al. Loss of neurons of origin of the adrenergic projection to cerebral cortex (nucleus locus ceruleus) in senile dementia. Neurology. 1982;32:164–168. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matthews KL, et al. Noradrenergic changes, aggressive behavior, and cognition in patients with dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:407–416. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilson RS, et al. Neural reserve, neuronal density in the locus ceruleus, and cognitive decline. Neurology. 2013;80:1202–1208. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182897103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Clewett DV, et al. Neuromelanin marks the spot: identifying a locus coeruleus biomarker of cognitive reserve in healthy aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;37:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chan-Palay V, Asan E. Alterations in catecholamine neurons of the locus coeruleus in senile dementia of the Alzheimer type and in Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia and depression. J Comp Neurol. 1989;287:373–392. doi: 10.1002/cne.902870308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Foote SL, et al. Impulse activity of locus coeruleus neurons in awake rats and monkeys is a function of sensory stimulation and arousal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:3033–3037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Activity of norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci. 1981;1:876–886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00876.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hunsley MS, Palmiter RD. Norepinephrine-deficient mice exhibit normal sleep-wake states but have shorter sleep latency after mild stress and low doses of amphetamine. Sleep. 2003;26:521–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kelberman MA, Vazey EM. New Pharmacological Approaches to Treating Non-Motor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease. Curr Pharmacol Rep. 2016;2:253–261. doi: 10.1007/s40495-016-0071-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Doty RL. Olfactory dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:329–339. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rey NL, et al. Locus coeruleus degeneration exacerbates olfactory deficits in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:426e421–411. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grenhoff J, et al. Noradrenergic modulation of midbrain dopamine cell firing elicited by stimulation of the locus coeruleus in the rat. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1993;93:11–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01244934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gaval-Cruz M, et al. Chronic loss of noradrenergic tone produces beta-arrestin2-mediated cocaine hypersensitivity and alters cellular D2 responses in the nucleus accumbens. Addict Biol. 2016;21:35–48. doi: 10.1111/adb.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schank JR, et al. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase knockout mice have alterations in dopamine signaling and are hypersensitive to cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2221–2230. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Miguelez C, et al. The locus coeruleus is directly implicated in L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in parkinsonian rats: an electrophysiological and behavioural study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Steenland K, et al. Late-life depression as a risk factor for mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease in 30 US Alzheimer’s disease centers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;31:265–275. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schapira AHV, et al. Non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18:435–450. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bremner JD, et al. Noradrenergic mechanisms in stress and anxiety: I. Preclinical studies. Synapse. 1996;23:28–38. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199605)23:1<28::AID-SYN4>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McCall JG, et al. CRH Engagement of the Locus Coeruleus Noradrenergic System Mediates Stress-Induced Anxiety. Neuron. 2015;87:605–620. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bunney WE, Jr, Davis JM. Norepinephrine in depressive reactions. A review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;13:483–494. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01730060001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schildkraut JJ. The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: a review of supporting evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 1965;122:509–522. doi: 10.1176/ajp.122.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Simson PE, Weiss JM. Altered activity of the locus coeruleus in an animal model of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1988;1:287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ordway GA, et al. Elevated tyrosine hydroxylase in the locus coeruleus of suicide victims. J Neurochem. 1994;62:680–685. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62020680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim Y, et al. Whole-Brain Mapping of Neuronal Activity in the Learned Helplessness Model of Depression. Front Neural Circuits. 2016;10:3. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2016.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Szot P, et al. Depressive-like behavior observed with a minimal loss of locus coeruleus (LC) neurons following administration of 6-hydroxydopamine is associated with electrophysiological changes and reversed with precursors of norepinephrine. Neuropharmacology. 2016;101:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Carter ME, et al. Tuning arousal with optogenetic modulation of locus coeruleus neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1526–1533. doi: 10.1038/nn.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vazey EM, Aston-Jones G. Designer receptor manipulations reveal a role of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic system in isoflurane general anesthesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:3859–3864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310025111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Musiek ES, et al. Sleep, circadian rhythms, and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Exp Mol Med. 2015;47:e148. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Poe GR. Sleep Is for Forgetting. J Neurosci. 2017;37:464–473. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0820-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zeitzer JM. Control of sleep and wakefulness in health and disease. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2013;119:137–154. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396971-2.00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Raskind MA, Peskind ER. Neurobiologic bases of noncognitive behavioral problems in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1994;8(Suppl 3):54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hoogendijk WJ, et al. Increased activity of surviving locus ceruleus neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:82–91. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199901)45:1<82::aid-art14>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Goldstein DS. Biomarkers, mechanisms, and potential prevention of catecholamine neuron loss in Parkinson disease. Adv Pharmacol. 2013;68:235–272. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-411512-5.00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Eldrup E, et al. CSF and plasma concentrations of free norepinephrine, dopamine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), and epinephrine in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 1995;92:116–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1995.tb01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Szot P, et al. Compensatory changes in the noradrenergic nervous system in the locus ceruleus and hippocampus of postmortem subjects with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurosci. 2006;26:467–478. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4265-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Haidkind R, et al. Effects of partial locus coeruleus denervation and chronic mild stress on behaviour and monoamine neurochemistry in the rat. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(02)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Crimins JL, et al. Electrophysiological changes precede morphological changes to frontal cortical pyramidal neurons in the rTg4510 mouse model of progressive tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:777–795. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1038-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rudy CC, et al. The role of the tripartite glutamatergic synapse in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Dis. 2015;6:131–148. doi: 10.14336/AD.2014.0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Logan T, et al. alpha-Synuclein promotes dilation of the exocytotic fusion pore. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:681–689. doi: 10.1038/nn.4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chesselet MF, et al. A progressive mouse model of Parkinson’s disease: the Thy1-aSyn (“Line 61”) mice. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9:297–314. doi: 10.1007/s13311-012-0104-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jucker M, Walker LC. Pathogenic protein seeding in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:532–540. doi: 10.1002/ana.22615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Braak H, Del Tredici K. Alzheimer’s pathogenesis: is there neuron-to-neuron propagation? Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:589–595. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0825-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Stratmann K, et al. Precortical Phase of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)-Related Tau Cytoskeletal Pathology. Brain Pathol. 2016;26:371–386. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wu JW, et al. Neuronal activity enhances tau propagation and tau pathology in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1085–1092. doi: 10.1038/nn.4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ulusoy A, et al. Caudo-rostral brain spreading of alpha-synuclein through vagal connections. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:1119–1127. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201302475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Surmeier DJ, et al. Parkinson’s Disease Is Not Simply a Prion Disorder. J Neurosci. 2017;37:9799–9807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1787-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.McMillan PJ, et al. Differential response of the central noradrenergic nervous system to the loss of locus coeruleus neurons in Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2011;1373:240–252. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Seidel K, et al. The brainstem pathologies of Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain Pathol. 2015;25:121–135. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Brunnstrom H, et al. Differential degeneration of the locus coeruleus in dementia subtypes. Clin Neuropathol. 2011;30:104–110. doi: 10.5414/npp30104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Eser RA, et al. Selective Vulnerability of Brainstem Nuclei in Distinct Tauopathies: A Postmortem Study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2018;77:149–161. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlx113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Irwin DJ, et al. Deep clinical and neuropathological phenotyping of Pick disease. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:272–287. doi: 10.1002/ana.24559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Takauchi S, et al. Coexistence of Pick bodies and atypical Lewy bodies in the locus ceruleus neurons of Pick’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1995;90:93–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00294465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Xu ZQ, et al. Galanin/GMAP- and NPY-like immunoreactivities in locus coeruleus and noradrenergic nerve terminals in the hippocampal formation and cortex with notes on the galanin-R1 and -R2 receptors. J Comp Neurol. 1998;392:227–251. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980309)392:2<227::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Weinshenker D, Holmes PV. Regulation of neurological and neuropsychiatric phenotypes by locus coeruleus-derived galanin. Brain Res. 2016;1641:320–337. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Morita Y, et al. Postnatal development of preproenkephalin mRNA containing neurons in the rat lower brainstem. J Comp Neurol. 1990;292:193–213. doi: 10.1002/cne.902920204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Koylu EO, et al. CART peptides colocalize with tyrosine hydroxylase neurons in rat locus coeruleus. Synapse. 1999;31:309–311. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(19990315)31:4<309::AID-SYN10>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Castren E, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor messenger RNA is expressed in the septum, hypothalamus and in adrenergic brain stem nuclei of adult rat brain and is increased by osmotic stimulation in the paraventricular nucleus. Neuroscience. 1995;64:71–80. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00386-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Conner JM, et al. Distribution of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) protein and mRNA in the normal adult rat CNS: evidence for anterograde axonal transport. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2295–2313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02295.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sampaio TB, et al. Neurotrophic factors in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases: implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Neural Regen Res. 2017;12:549–557. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.205084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Counts SE, et al. Neuroprotective role for galanin in Alzheimer’s disease. EXS. 2010;102:143–162. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0346-0228-0_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Liu X, et al. Norepinephrine Protects against Amyloid-beta Toxicity via TrkB. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44:251–260. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Counts SE, Mufson EJ. Noradrenaline activation of neurotrophic pathways protects against neuronal amyloid toxicity. J Neurochem. 2010;113:649–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Liu KY, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the human locus coeruleus: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;83:325–355. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Mathis CA, et al. Small-molecule PET Tracers for Imaging Proteinopathies. Semin Nucl Med. 2017;47:553–575. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wang LY, et al. Prazosin for the treatment of behavioral symptoms in patients with Alzheimer disease with agitation and aggression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:744–751. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ab8c61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.McMorris T. Developing the catecholamines hypothesis for the acute exercise-cognition interaction in humans: Lessons from animal studies. Physiol Behav. 2016;165:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Mather M, Harley CW. The Locus Coeruleus: Essential for Maintaining Cognitive Function and the Aging Brain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2016;20:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Pamphlett R. Uptake of environmental toxicants by the locus ceruleus: a potential trigger for neurodegenerative, demyelinating and psychiatric disorders. Med Hypotheses. 2014;82:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Berridge CW, Waterhouse BD. The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;42:33–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sanchez-Padilla J, et al. Mitochondrial oxidant stress in locus coeruleus is regulated by activity and nitric oxide synthase. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:832–840. doi: 10.1038/nn.3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ishimatsu M, Williams JT. Synchronous activity in locus coeruleus results from dendritic interactions in pericoerulear regions. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5196–5204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05196.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Van Bockstaele EJ, et al. Expression of connexins during development and following manipulation of afferent input in the rat locus coeruleus. Neurochem Int. 2004;45:421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2003.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Alvarez VA, et al. Frequency-dependent synchrony in locus ceruleus: role of electrotonic coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4032–4036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062716299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Aston-Jones G, et al. Impulse conduction properties of noradrenergic locus coeruleus axons projecting to monkey cerebrocortex. Neuroscience. 1985;15:765–777. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Botta-Orfila T, et al. Brain transcriptomic profiling in idiopathic and LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 2012;1466:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.van Dijk KD, et al. The proteome of the locus ceruleus in Parkinson’s disease: relevance to pathogenesis. Brain Pathol. 2012;22:485–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Corradini BR, et al. Complex network-driven view of genomic mechanisms underlying Parkinson’s disease: analyses in dorsal motor vagal nucleus, locus coeruleus, and substantia nigra. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:543673. doi: 10.1155/2014/543673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]