Abstract

Bioremediation of wastewater is gaining popularity over chemical treatment due to the greener aspect. The volume of literature containing algal biodegradation is small. Especially, removal of toxic materials like phenol from coke-oven wastewater using fast-growing cyanobacteria was not tried. The current study, therefore, targeted at bioremediation of phenol from wastewater using Leptolyngbya sp., a cyanobacterial strain, as a finishing step. Furthermore, the growth of the strain was studied under different conditions, varying phenol concentration 50–150 mg/L, pH 5–11, inoculum size 2–10% to assess its ability to produce lipid. The strain was initially grown in BG-11 as a reference medium and later in phenolic solution. The strain was found to sustain 150 mg/L concentration of phenol. SEM study had shown the clear difference in the structure of cyanobacterial strain when grown in pure BG-11 medium and phenolic solution. Maximum removal of phenol (98.5 ± 0.14%) was achieved with an initial concentration 100 mg/L, 5% inoculum size at pH 11, while the maximum amount of dry biomass (0.38 ± 0.02 g/L) was obtained at pH 7, initial phenol concentration of 50 mg/L, and 5% inoculum size. Highest lipid yield was achieved at pH 11, initial phenol concentration of 100 mg/L, and 5% inoculum size. Coke-oven wastewater collected from secondary clarifier of effluent treatment plant was also treated with the said strain and the removal of different pollutants was observed. The study suggests the utilization of such potential cyanobacterial strain in treating industrial effluent containing phenol.

Keywords: Phenol, Bioremediation, Cyanobacteria, Leptolynbga sp., Coke-oven wastewater

Introduction

With the surge of the industrial revolution, industrial wastewater is one of the major causes of water pollution. Each industrial sector produces its own particular combination of pollutants (Hangchang 2009). The greatest source of water pollution accounting for more than half of the volume is from the most deadly organic pollutants of which phenol is a significant contributor (Sadhu et al. 2013) and has several adverse effects on human health even at low concentrations. Due to its inherent toxic, carcinogenic, mutagenic, and teratogenic nature, it has been included in the list of priority pollutants as shown by EPA (1979). Phenol and phenolic compounds, commonly known as ‘Phenols’, contribute an adverse impact on the ecosystem if it is discharged to the environment without any proper treatment (Kulkarni and Kaware 2013). Phenols are often found in the effluents coming from several industries such as steel, paper and pulp, textiles, gas and coke, fertilizers, pesticides, and oil refineries, etc. (Sadhu et al. 2013). Acute exposure to phenol causes disorders of the central nervous system, reduced blood pressure and cardiac depression and can damage blood, liver, and kidney (Kulkarni and Kaware 2013). The toxic levels usually range between the concentrations of 10–24 mg/L for human and the toxicity level for fish between 9–25 mg/L (Kulkarni and Kaware 2013). Lethal concentration of phenol in blood is around 150 mg/100 mL (Kulkarni and Kaware 2013). Keeping in view of the abundant occurrence of phenol in industrial effluent and its toxic effects, several technologies have been employed to remove phenol from wastewater below the permissible limit (Jain et al. 2004; Banat et al. 2000). The choice of treatment depends upon the concentration, volume of effluent, and cost of the treatment. Different conventional processes, such as biosorption (Michalowicz and Duda 2007), adsorption on activated carbon (Sezos et al. 2007), bacterial and chemical oxidation (Wilberg et al. 2000), electrochemical techniques, irradiation, etc., could be applied (Dakhil 2013). However, all of these methods suffer from several shortcomings such as high costs, incomplete purification, the formation of hazardous by-products, low efficiency, and applicability to a limited concentration range, etc (Bohdziewicz et al. 2012). Bioremediation process through the application of microorganism to degrade pollutant in environmental safe manner is a proven technology. In most of the effluent treatment plants, the residual amount of the chemical compounds is being degraded by the microorganism as a secondary process. Among the bacterial genera, Gram-negative bacteria like Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter calcoaceticu are capable of degrading up to 75% in 24 h (Tian et al. 2017). Similarly, Liu et al. (2016) successfully isolated a phenol-degrading bacterium strain PA from the effluent of petrochemical wastewater, which was efficient in removing 91.6% of the initial 800 mg/L phenol within 48 h, and had a tolerance of phenol concentration as high as 1700 mg/L. However, the biodegradation using bacterial cultures produces sludge as a secondary pollutant and the disposal of such bacterial sludge becomes trouble for the industry from environmental and aesthetic point of view (Karn and Chakrabarti 2015). Phycoremediation using algae can be a better option owing to its intrinsic possibility of production of biofuel from algal biomass. The advantages of algae-based treatment include cost-effectiveness; low energy requirement, reduction in sludge formation, and production of algal biomass. Algae biofuel is non-toxic, contains no sulfur, and is highly biodegradable (Ghasemi et al. 2012). The possible use of the unicellular chrysophyte and Ochromonas danica (Semple and Cain 1996) had been investigated for the degradation of phenols in the dark and in aerobic conditions. Such alga was able to degrade exogenous phenol through the meta-cleavage pathway (Semple and Cain 1996). In general, the most frequently used algae in wastewater treatment are green unicellular or coenobic algae (Pinto et al. 2002). In addition, since the intensive algal growth in open ponds causes an increase in pH which can be tolerated by cyanobacteria, algal systems with filamentous cyanobacteria have been proposed for the secondary and tertiary treatments of wastewater (Abdel et al. 2012). Both cyanobacteria and green algae are found to be sensitive to phenolics whose toxicity is related to the number and to the polarity of the substituents on the aromatic ring (Pinto et al. 2002) and can remove the phenol to the extent of mg/L level. However, some algal strains can metabolize phenyl propanoids such as α-asarone at 10−4 M (Pollio et al. 1993). While phenols show high toxicity to many algae, both cyanobacteria and eukaryotic microalgae are capable of bio-transforming aromatic compounds, including phenols, and degradation products may act as intermediate metabolites in algal metabolism (Semple and Cain 1996; Subashchandrabose et al. 2013).

Effluents from the coke-oven plant for production of metallurgical coke by carbonizing coking coal at higher temperature is another great source of phenols. Coke-oven wastewater is an inflexible chemical wastewater containing many toxic pollutants (Gao et al. 2015). In the present study, both synthetic wastewater and real wastewater collected from secondary clarifier of coke-oven effluent treatment plant had been used to remove phenol. The cyanobacterial strain, Leptolyngbya sp., was used for such purpose. The possibility of biofuel production was assessed by measuring the biomass and lipid content of cyanobacterial strain during removal of phenol (Ghose 2002). Thus, the abatement of phenol through cost-effective and environmental–friendly manner with a notable possibility of biofuel production is the thrust of the present study. The purpose of the study is to use Leptolyngbya sp. to treat coke-oven wastewater with the biodegradation of phenol present in coke-oven effluent.

Materials and methods

All the chemicals were of AR grade and purchased from MERCK. Lipid standards were procured from Sigma. The analytical instruments used were weighing machine (Model No. XR205SM-DR, Precisa Gravimetrics, AG/Switzerland), Probe sonicator, UV–visible Spectrophotometer (UV 1601, Shimadzu) and Orion ion meter (Orion 94-06).

Collection, cultivation, and growth study of collected sample

The strain was collected from East Kolkata Wetland (EKW), popularly known as the “kidney of the city”. This site was selected as it is included in the list maintained under Ramsar Bureau established under the article 8 of the Ramsar Convention and had given this wetland the recognition of a ‘Wetland of International Importance’ (Kundu et al. 2007). East Kolkata Wetland is a unique example of innovative resource reuse system through productive activities and confirms its suitability for the conservation of diverse effects of flora and fauna. EKW being the world’s largest natural recycling center for soluble and solid wastes are expected to be the rich source of bioremediants as well as phytoplankton mainly dominated by Cyanophyceae. The microbial resource mapping of this important Ramsar Site indicated the presence of microorganisms from 12 different main bacterial phyla, thus, revealing the rich natural microbial resource at East Calcutta Wetland (Raychaudhuri et al. 2008). The biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds, coming from herbicide or pesticide, by the bioremediants present in the wetland had proved their capability to degrade the aromatic compounds and this led the present investigators to collect the cyanobacterial samples from the present site. The strain was morphologically identified at Central National Herbarium, Botanical Survey of India. It was cultivated autotrophically in BG-11 media and incubated in algal Incubator [LAB-X, India] under illumination at 2400 lx with light and dark cycle of 16 and 8 h, respectively. The test strain grew in the media for 2 weeks and was sub-cultured into fresh autoclaved media thereafter. To study the growth of cyanobacterial strain, it was grown in the BG-11 medium for 14 days. Samples were collected at specific time intervals and harvested by centrifugation (ELTEK centrifuge TC 8100 F) at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The cyanobacterial biomass was collected and dried overnight at 60 °C. Finally, the weight of dry biomass was measured.

Characterization of collected sample

Scanning electron microscope study was done for topographical characterization of both native cells and cyanobacterial cells after treatment with simulated solutions of phenol using scanning electron microscope (JEOL JSM-6700 FE, TOKYO). The cyanobacterial sample was grown in 50 mL of BG 11 medium containing 100 mg/L phenol for 10 days. The biomass was harvested by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min. It was then washed with distilled water for two times to get rid of any chemicals and dried overnight at 60 °C. The phenol treated cyanobacterial sample was thus prepared and used for SEM study.

Growth of collected strain in simulated solution of phenol

The stock solution of phenol (100 mg/L) was prepared by dissolving the requisite amount of phenol (MERCK) in BG 11 medium following the standard protocol (Clesceri et al. 1996). The solution of a required concentration of phenol was prepared by diluting the stock solution with the BG-11 medium. Then, the cyanobacterial strain was grown in simulated phenol solution having an initial concentration of 100 mg/L. Two experimental conditions were maintained. In the first case, pH was not adjusted. The test strain was grown in simulated phenol solution at its own pH. In the second one, pH was adjusted at 7. The flasks were incubated in algal Incubator [LAB-X, India] under illumination at 2400 lx with light and dark cycle of 16 and 8 h, respectively. Samples were collected at specific time intervals and harvested by centrifugation (ELTEK centrifuge TC 8100 F) at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The cyanobacterial biomass was collected and dried overnight at 60 °C. Finally, the weight of dry biomass was measured.

Phenol degradation and growth capacity of the collected strain in synthetic wastewater and lipid extraction

The present strain was grown in simulated solutions of phenol and prepared by diluting the stock solution of phenol with the requisite amount of BG-11 medium. Three input parameters such as initial concentration of phenol, pH, and inoculum size were varied individually in the range of 50 to 150 mg/L, 5 to 11, and 2 to 10%, respectively, during bioremediation of phenol. The volume of solution was maintained 100 mL in each case. While the initial concentration of phenol was varied from 50 to 150 mg/L, inoculum size and pH were kept at 5% and 7, respectively. Similarly, the initial concentration of phenol and pH was maintained at 100 mg/L and 7, when inoculum size was varied from 2 to 10%. During the study on the effect of pH on phenol removal, initial concentrations of phenol and inoculum size remained same as 100 mg/L and 5%. After inoculation, the culture broth was incubated in an algal incubator at 25 °C for 14 days with an illumination of 2400 lx having dark and light cycles of 16 and 8 h, respectively. The samples were collected after 2 day interval and analyzed for residual phenol concentration using standard protocol (Clesceri et al. 1996), and thus, percentage removal of phenol was measured in each case. Concurrently, the growth of cyanobacterial strain in terms of dry biomass was measured at various input conditions.

To assess the lipid content of the present strain, the biomass obtained during the growth of strain in BG 11 medium was disrupted using sonicator at a resonance of 8 kHz for 10 min. After cell disruption step, the total lipids were extracted using modified Bligh and Dyer method (1959). In this method, a solvent mixture of chloroform and methanol in the ratio of 2:1 was used to extract lipids. The lower organic phase containing lipid dissolved in chloroform was collected, while the upper aqueous phase was discarded. The lipid yield was analyzed spectrophotometrically using vanillin reagent at 625 nm. Similarly, to observe the effect of phenol on lipid content, the cyanobacterial biomass obtained after 12 days of incubation in simulated phenol solution were collected. The lipids were extracted and analyzed following the methods as stated above.

Collection and analysis of real coke-oven wastewater and treatment with collected strain

Coke-oven wastewater was collected from secondary clarifier outlet of effluent treatment plant of nearby coke-oven plant situated in Durgapur, India. Since the coke-oven wastewater contains an array of pollutants, a series of physical, chemical, and biological treatment has been performed in the effluent treatment plant. After biological treatment, the wastewater goes to the secondary clarifier to separate the bacterial biomass from the effluent and the clean effluent is discharged. The present researchers collected the effluent from the outlet of the secondary clarifier and analyzed for pollutant concentration using standard protocol (Clesceri et al. 1996). It was found that the concentrations of pollutants were still higher than permissible limits. Therefore, the effluent from secondary clarifier was collected and subjected to bioremediation using collected strain. The test strain was grown in the real wastewater. The flasks were incubated in algal incubator [LAB-X, India] under illumination at 2400 lx with light and dark cycle of 16 and 8 h, respectively. The cell suspensions were collected after 6th and 12th day and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was separated and analyzed for residual pollutant concentration using standard protocols.

Statistical analysis

All results were expressed as Mean ± SD of four experiments. Student’s t test was carried out to find out whether the changes were significant (p < 0.05 was considered significant).

Results and discussion

Identification and growth of collected strain in BG-11 medium

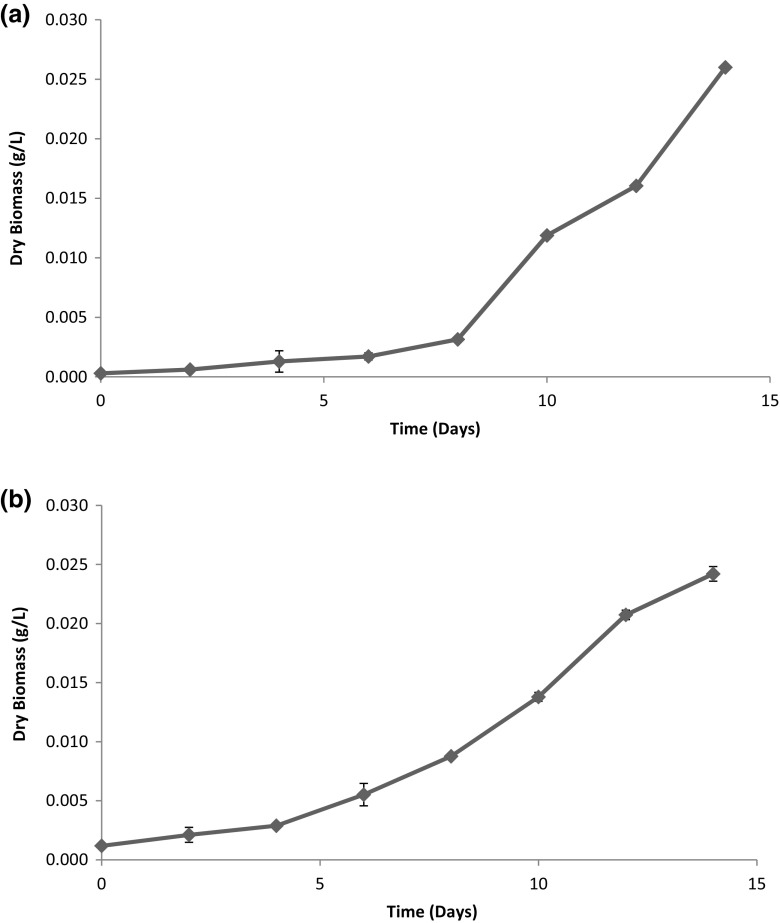

The strain as used in the present study was morphologically identified as Leptolyngbya sp., a cyanobacterial strain, by Central National Herbarium, Botanical Survey of India. Leptolyngbya sp. used in this study was rod-shaped clusters in nature. The growth of cyanobacterial species had been measured in terms of its dry biomass and is shown in Fig. 1. It was found that lag phase extended up to 4 days and stationary phase started after 14 days. Dry biomass increased from 0.0002 ± 0.00002 to 0.017 ± 0.0002 g/L during log phase.

Fig. 1.

Growth curve of cyanobacterial species in BG-11 media

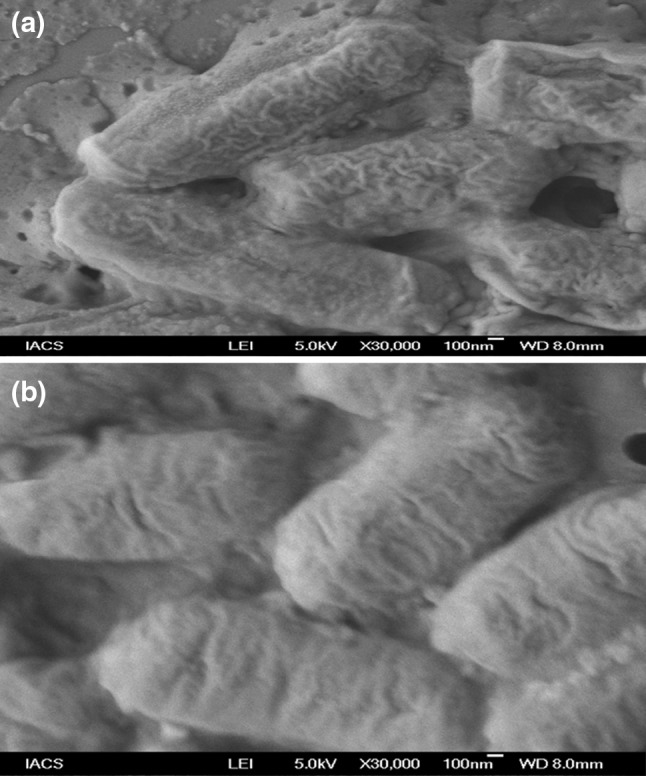

Characterization of cyanobacterial sample

Scanning electron micrographs of native cyanobacterial strain and strain after treatment with phenol solution are shown in Fig. 2a, b. Both the micrographs represented well-defined rod-shaped clusters of Leptolyngbya sp. at 30,000 magnifications. In Fig. 2a, some undulations on the surface of cyanobacteria were noticed. However, such undulations were absent after treatment with the simulated phenolic solution. Therefore, it can be presumed that the cyanobacterial strain was capable to withstand the present concentration of phenol of 100 mg/L and remained alive in spite of harmful nature of phenol.

Fig. 2.

a Scanning electron micrograph of cyanobacterial strain in BG-11 media. b Scanning electron micrograph of cyanobacterial strain grown in simulated phenol solution

Growth of Leptolyngbya sp. in simulated phenolic solution at various pH conditions

The objective of such variation of pH was to assess the robustness of cyanobacterial strain in terms of its sustenance at high concentration of phenol at different pH conditions. Leptolyngbya sp had been grown in simulated phenolic solution with the initial concentration of 100 mg/L where pH was not adjusted. From the growth curve, as shown in Fig. 3a, it is observed that the strain was capable of sustaining high concentration of phenol. Extended lag phase of 6 days was observed during growth in phenolic solution. This might be due to the time required for acclimatization of the test strain in phenolic solution. The log phase started from 6 days and continued up to 14 days; however, a sudden sharp rise in growth curve during log phase was noticed in contrast to growth curve in BG-11 media. Furthermore, the dry biomass of the said strain obtained from BG-11 medium after 14 days of growth (0.017 g/L ± 0.0002) was less than that obtained in case of simulated phenolic solution (0.026 g/L ± 0.0002) at acidic pH. This might be due to the uptake of phenol as nutrient by cyanobacterial strain in addition to the nutrients present in BG-11 medium. A typical pathway for metabolizing an aromatic compound like phenol is to dihydroxylate the benzene ring to form a catechol derivative and then to open the ring through ortho- or metaoxidation (Mahiudddin et al. 2012). Catechol is oxidized via ortho-cleavage pathway by catechol 1, 2-dioxygenase, or by meta-pathway to 2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde by catechol 2, 3-dioxygenase. The final products of both the pathways enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle and, subsequently, are degraded (Mahiudddin et al. 2012). In the second case, Leptolyngbya sp. was grown in the same phenolic solution of 100 mg/L concentration; however, pH was adjusted at 7. The growth curve is shown in Fig. 3b. Here, it is noticed that lag phase extended up to 4 days and log phase started immediately after 4 days. The biomass obtained in such case (0.024 g/L ± 0.0006) was almost similar to that obtained when cyanobacterial strain was grown in 100 mg/L phenol solution (0.026 g/L ± 0.0002) at acidic pH and higher than that obtained when grown in BG-11 media (0.017 g/L ± 0.0002). Therefore, it can be stated that the cyanobacterial strain remained active over a wide pH range. The similar observation was reported by Ullrich et al. (1990).

Fig. 3.

a Growth curve of cyanobacteria in phenolic solution (100 mg/L). b Growth curve of cyanobacteria in phenolic solution (100 mg/L) at pH 7

Phenol degradation capacity of Leptolyngbya sp. in synthetic wastewater

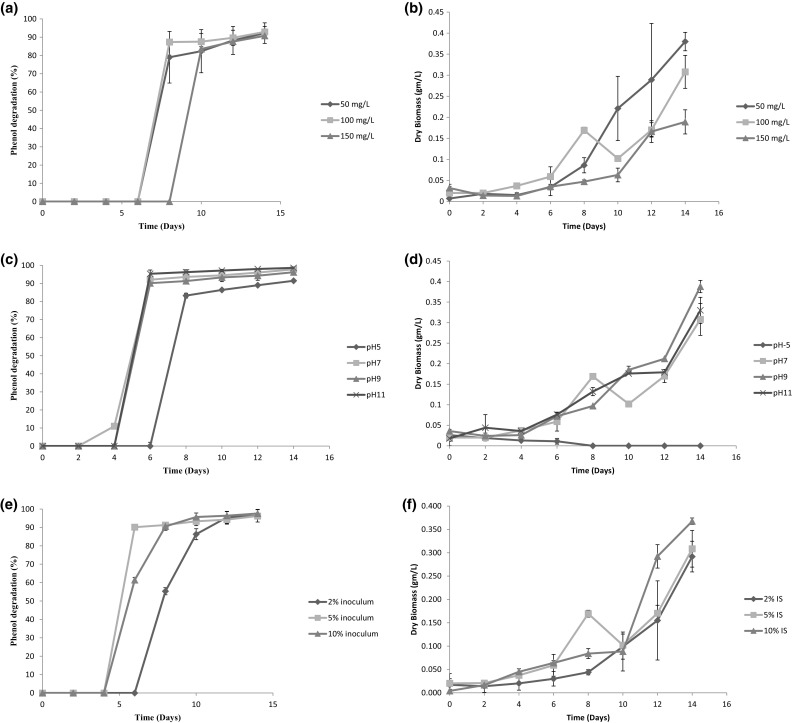

To assess the capability of the strain to degrade phenol and its sustenance at higher concentrations of the said pollutant, the cyanobacterial strain was grown in simulated phenol solution. The initial concentration of phenol was varied in the range of 50–150 mg/L. The percentage removal of phenol by cyanobacteria with time at different concentrations of phenol is shown in Fig. 4a. It is observed that the cyanobacterial strain was able to tolerate the phenol concentrations up to 150 mg/L, but higher concentration (> 150 mg/L) was found to be detrimental to the present strain. The maximum degradation of phenol (92.88 ± 3%) occurred at an initial concentration of 100 mg/L. However, at 150 mg/L concentration, almost similar removal (90.76 ± 0.07%) was achieved. Therefore, it might be stated that the present cyanobacterial strain was efficient enough to degrade phenol at higher concentration. Algae can grow both autotrophically and heterotrophically. The removal of phenol at higher concentration might be due to the heterotrophic growth of cyanobacterial strain in simulated phenol solution. The lack of removal of phenol during the initial days opted out the possibility of biosorption of phenol onto cyanobacterial biomass. Again, due to quick acclimatization of cyanobacterial strain to the lower concentration of phenol such as 50 and 100 mg/L, the removal of 79.04 ± 14.13 and 87.34 ± 0.16% was observed on the 8th day in contrast to 83.55 ± 1.20% removal on the 10th day for 150 mg/L phenol solution. A sudden rise in removal was noticed in all the cases during log phase. This might be due to the attainment of maximum activity of cyanobacterial strain at these conditions. However, percentage removal for all the phenolic solutions after 14 days was observed to be almost same (≥ 90%), as shown in Fig. 4a.

Fig. 4.

a Phenol degradation at different initial phenol concentrations. b Growth curve of cyanobacteria at different initial phenol concentrations. c Phenol degradation at different pH. d Growth curve of cyanobacteria at different pH of phenolic solution. e Phenol degradation at different inoculum percentage of cyanobacteria. f Growth curve of cyanobacteria at different inoculum concentrations

To evaluate the phenol degradation capacity of cyanobacterial strain at different pH, the strain was grown in synthetic wastewater having the initial phenol concentration of 100 mg/L with a varying pH of 5, 7, 9, and 11. The variation of percentage removal of phenol with time at different pH is shown in Fig. 4c. Phenol started to bioremediate after 6 days at pH 5, 4 days at pH 9 and 11, and 2 days at pH 7. Therefore, it could be postulated that the present cyanobacterial strain preferred neutral to alkaline pH for bioremediation. It was further observed that phenol degradation capacity of cyanobacterial strain was more at pH 11 (98.59 ± 0.14%). Since the native location of the present cyanobacterial strain was EKW and pH of wastewater in this region generally lies in the alkaline range, the cyanobacterial strain naturally showed better removal capacity at the alkaline range.

The effect of inoculum size on phenol degradation capacity was also been studied. Inoculum size vis-à-vis inoculum concentration was varied from 2 to 10% of working solution having constant initial phenol concentration of 100 mg/L. The results are shown in Fig. 4c. From the figure, it is evident that percentage removal of phenol was directly proportional to inoculum size. Maximum removal of phenol (97.57 ± 2.25%) was observed with 10% inoculum size. This was expected, because, with higher inoculum concentration, more number of cells was exposed to the solution causing greater removal of phenol (Issa et al. 2007).

In the present study, we found that there was no removal of phenol during lag phase of growth of Leptolyngbya sp. As biosorption of phenol was a fast phenomenon, which was not the case in the present study, it may be inferred that phenol was not adsorbed by cyanobacteria. After acclimatization of the strain in simulated phenol solutions of different concentration, it started to remove phenol.

Growth of Leptolyngbya sp. in synthetic wastewater

With the intention of ascertaining simultaneous growth of the said strain along with phenol degradation, the cyanobacterium was grown in different phenolic solution. From the growth curve of Fig. 4b, it could be seen that the strain was capable of sustaining high concentration of phenol. The stretched lag phase of 6 days was observed during growth in all phenolic solution. This might be due to the time required for adaptation of the test strain in phenolic solution. After 6 days, the log phase started and continued up to 14 days. Yet again, after quick adaptation, the cyanobacterial strain was found to grow efficiently in 50 and 100 mg/L. The probable reason might be the uptake of phenol as a nutrient by cyanobacterial strain in addition to the nutrients present in the BG-11 medium. In such case, the dry biomasses obtained were 0.38 ± 0.02 and 0.308 ± 0.039 g/L which was higher than the 0.189 ± 0.028 g/L when grown in 150 mg/L. However, the strain was capable to grow in various phenolic solutions, although Leptolyngbya sp. showed proficient growth in 50 mg/L phenolic solution. The growth of cyanobacterial strain was also determined, where, Leptolyngbya sp., the strain was grown in simulated phenolic solution with the initial concentration of 100 mg/L at different pH. It is found from growth curve of Fig. 4d that the strain was unable to grow at acidic pH; however, it showed consistent growth at alkaline pH. Furthermore, the cyanobacterial strain was grown in 100 mg/L varying inoculum size from 2 to 10% to see the effect of inoculum size on its growth. From Fig. 4f, it is found that growth of biomass was directly proportional to inoculum size. This was obvious because of the fact that the higher inoculum concentration was directly proportional to amount of dry biomass produced.

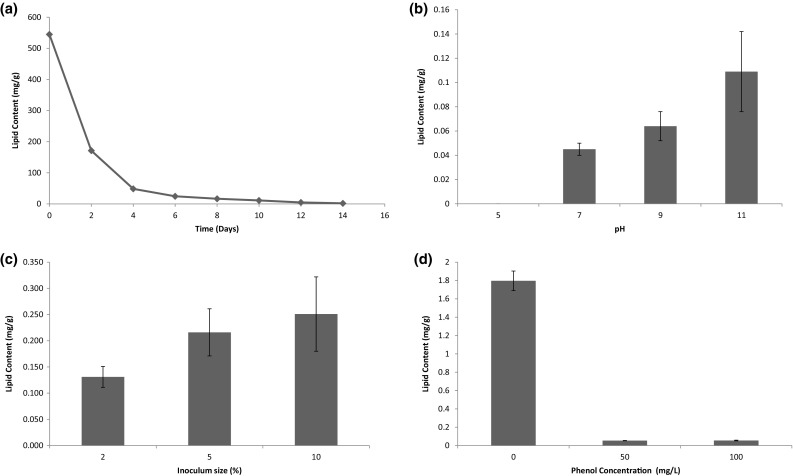

Extraction of lipid from cyanobacteria strain after treatment with phenol

In the present study, the choice of microalgae over bacteria for degradation of phenol was done based on the ability of production of biofuel by the former. Initially, the lipid content of the cyanobacterial strain was assessed when it was grown in 100 mL BG-11 media for 14 days with 5% inoculation at initial pH 7. The variation of lipid content with days is shown in Fig. 5a. The lipid content appeared to decrease gradually due to increase in biomass. Initially, the extremely low amount of biomass (0.0002 g/L) showed high amount of lipid (544.88 mg/g). As the biomass grown, lipid did not enhance at the same rate. The lipid content of cyanobacterial strain was also assessed in simulated phenol solution at various input conditions mentioned earlier. The cyanobacterial strain was grown in 100 mL simulated phenol solution. After 12 days, the cyanobacterial biomass was harvested and lipid was extracted. The variations of lipid contents with pH, inoculum size, and initial concentration of phenol are shown in Fig. 5b–d, respectively. From Fig. 5b, it could be seen that maximum lipid, i.e., 0.109 ± 0.033 mg/g was obtained at pH 11. From Fig. 5c, it was seen that lipid content increased from 0.131 ± 0.02 to 0.251 ± 0.071 mg/g when inoculum size increased from 2 to10%. The variation of lipid with the initial concentration of phenol is shown in Fig. 5d. It might be concluded that lipid yield was retarded in phenolic solution compared to BG 11 medium.

Fig. 5.

a Lipid content of cyanobacteria in BG-11 media. b Lipid content of cyanobacteria at different pH. c Lipid content of cyanobacteria at different inoculum percentage of cyanobacteria. d Lipid content varying phenol concentration

Treatment of coke-oven wastewater collected from secondary clarifier wastewater using Leptolyngbya sp.

Treated coke-oven wastewater was collected from secondary clarifier of local coke-oven effluent treatment plant and analyzed. The potential of cyanobacterial strain in wastewater treatment was studied by growing it in treated coke-oven wastewater. After collection, the wastewater was treated directly with cyanobacteria without the addition of any chemicals. The concentrations of different pollutants present in real wastewater after treatment with cyanobacterial strain for 6 and 12 days are shown in Table 1. The permissible limits of such pollutants were also listed in the table. The pollutants present in wastewater were found to be reduced to a great extent after treatment with cyanobacterial strain and removal after 12 days was more than that after 6 days. From the table, it is also noted that though phenol concentration had almost reached the permissible limit, the concentrations of other pollutants were still higher. Thus, a comprehensive study by varying process conditions is needed further to meet the environmental agency regulation.

Table 1.

Concentration of various pollutants before and after treatment with Leptolyngbya sp.

| Parameter | Concentration before cyanobacterial treatment (mg/L) | Concentration after 6 days treatment (mg/L) | Concentration after 12 days treatment (mg/L) | Permissible limit of pollutant (mg/L) in Inland surface water* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol | 1.88 | 1.73 | 1.05 | 1 |

| Cyanide | 2.45 | 1.44 | 1.42 | 0.2 |

| Nitrate | 67 | 53.8 | 49.4 | 10 |

| Phosphate | 41.5 | 21.5 | 17.3 | 5 |

| Sulfate | 84 | 65 | 57 | Not reported |

Conclusion

In the present study, the bioremediation of phenol from wastewater using a cyanobacterial strain Leptolyngbya sp. was examined. The cyanobacterial strain used in the present study had morphologically been identified as Leptolyngbya sp. by Botanical Survey of India, Kolkata. SEM study revealed that the present rod-shaped strain could withstand even 100 mg/L concentration of phenol. The strain was initially grown in BG-11 as a reference medium and later in synthetic wastewater at different phenol concentration, pH, and inoculum size. The strain was found to grow even at 150 mg/L concentration of phenol. Maximum removal of phenol (98.5 ± 0.14%) was achieved with initial concentration 100 mg/L, 5% inoculum size at pH 11, while maximum amount of dry biomass (0.38 ± 0.02 g/L) was obtained at pH 7, initial phenol concentration of 50 mg/L and 5% inoculum size. As expected, inoculum size of cyanobacteria had the direct effect on phenol degradation capacity.

Highest lipid yield was achieved at pH 11, initial phenol concentration of 100 mg/L, and 5% inoculum size. Coke-oven wastewater collected from secondary clarifier of effluent treatment plant was also been treated with the said strain and the removal of different pollutants had been observed. The study suggests the utilization of such potential cyanobacterial strain in treating industrial effluent containing phenol.

The cyanobacterial strain was used to degrade the pollutants, present in real wastewater collected from secondary clarifier of the local coke-oven effluent treatment plant. It showed the capability to remediate phosphate, nitrate, sulfate, cyanide, and phenol from such wastewater. Thus, the present cyanobacterial stain, Leptolyngbya sp., can be used for the treatment of industrial wastewater.

However, phenol containing media was found to be detrimental for lipid production from the cyanobacteria under study.

The conventional techniques to treat liquid and gaseous effluents pose economic and/or environmental limitations that prevent their further use. The technique of bioremediation, which uses microalgae or cyanobacteria for the removal of pollutants, is an emerging technology that has been highlighted due to its economic viability and environmental sustainability. So far, coke-oven wastewater had never been targeted by bioremediation using cyanobacteria, thereby lays the uniqueness of the present work.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Dept. of Chemistry, Dept. of Earth and Environmental Studies, and Dept. of Chemical Engineering, National Institute of Technology. We sincerely thank Gurpreet Kaur Wadhwa, M.Tech. student of Dept. of Earth and Environmental Studies, NIT Durgapur for helping with conducting the experiments.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdel RN, Homaidan Al AA, Ibraheem IBM. Microalgae and wastewater treatment. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2012;19:257–275. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banat FA, Bashir Al B, Asheh Al S, Hayajneh O. Adsorption of phenol by bentonite. Environ Pollu. 2000;107:391–398. doi: 10.1016/S0269-7491(99)00173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bligh EG, Dyer WM. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/y59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohdziewicz J, Kaminski G, Tytła M. The Removal of Phenols from wastewater through sorption on activated carbon. Arch Civil Eng Environ. 2012;2:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Clesceri LS, Greenberg AE, Trussell RR. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. Washington DC: APHA, AWWA, WPCF; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dakhil IH. Removal of phenol from industrial wastewater using sawdust. Inter J Eng Sci. 2013;3:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental standards. http://scclmines.com/env/Linkfile2.htm Accessed 08 June 2017

- Gao L, Li S, Wang Y, Sun H. Organic pollution removal from coke plant wastewater using coking coal. Water Sci Technol. 2015;72:158–163. doi: 10.2166/wst.2015.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi Y, Rasoulamini S, Naseri AT, Montazerinajafabady N, Mobasher MA, Dabbagh F. Microalgae biofuel potentials (review) Appl Biochem Microbiol. 2012;48:126–144. doi: 10.1134/S0003683812020068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose MK. Physico-chemical treatment of coke plant effluents for control of water pollution in India. Ind J Chem Technol. 2002;9:54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hangchang S. Point sources of pollution: local effects and its control. Oxford: Qian Yi, EOLSS; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Issa OM, Defarge C, Bissonnais YL, et al. Effects of the inoculation of cyanobacteria on the microstructure and the structural stability of a tropical soil. Plant Soil. 2007;290:209–219. doi: 10.1007/s11104-006-9153-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jain AK, Gupta VK, Jain S, Suhas Removal of chlorophenols using industrial wastes. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:1195–1200. doi: 10.1021/es034412u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karn SK, Chakrabarti S. Simultaneous biodegradation of organic (chlorophenols) and inorganic compounds from secondary sludge of pulp and paper mill by Eisenia fetida. Int J Recycl Org Waste Agricult. 2015;4:53–62. doi: 10.1007/s40093-015-0085-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni SJ, Kaware JP. Review on research for removal of phenol from wastewater. Int J Sci Res Publ. 2013;3:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu N, Pal M, Saha S (2007) East Kolkata Wetlands: a resource recovery system through productive activities. In: Proceedings of Taal: the 12th world lake conference, pp 868–881

- Liu Z, Wenyu X, Dehao L, Yang P, Zesheng L, Shusi L (2016) Biodegradation of Phenol by Bacteria Strain Acinetobacter calcoaceticus PA Isolated from Phenolic Wastewater, Int J Environ Res Public Health 13:300–308. 10.3390/ijerph13030300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mahiudddin Md, Fakhruddin AN, Abdullah Al M. Degradation of phenol via meta-cleavage pathway by Pseudomonas fluorescens PU1. ISRN Microb. 2012;741820:1–6. doi: 10.5402/2012/741820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michałowicz J, Duda W. Phenols—sources and toxicity. Pol J Environ Stud. 2007;16:347–362. [Google Scholar]

- Phenol ambient water quality criteria. Office of the planning and standards Environmental Protection Agency (1979), EPA, Washington, DC. https://nepis.epa.gov. Accessed 08 June 2017

- Pinto G, Pollio A, Previtera L, Temussi F. Biodegradation of phenols by microalgae. Biotechnol Lett. 2002;24:2047–2051. doi: 10.1023/A:1021367304315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pollio A, Pinto G, Ligrone R, Giovanni A. Effects of the potential allelochemical α-asarone on growth, physiology and ultrastructure of two unicellular green algae. J Appl Phycol. 1993;5:395–403. doi: 10.1007/BF02182732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raychaudhuri S, Mishra M, Nandy P, Thakur A. Waste management: a case study of ongoing traditional practices at East Calcutta. Am J Agri and Biol Sci. 2008;3:315–320. doi: 10.3844/ajabssp.2008.315.320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadhu K, Mukherjee A, Shukla Kr S, Adhikari K, Dutta S. Adsorptive removal of phenol from coke-oven wastewater using Gondwana shale, India: experiment, modeling and optimization. Desalination Water Treat. 2013;52:6492–6504. doi: 10.1080/19443994.2013.815581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semple KT, Cain RB (1996) Biodegradation of phenols by the alga Ochromonas danica. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:1265–1273. (0099-2240/96/$04.0010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sezos TM, Remoundaki E, Hatzikioseyian A. Workshop on clean production and nano technologies. Korea: Seoul; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Subashchandrabose SR, Ramakrishnan B, Megharaj M, Venkateswarlu K, Naidu R. Mixotrophic cyanobacteria and microalgae as distinctive biological agents for organic pollutant degradation. Environ Int. 2013;51:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian M, Du D, Zhou W, Zeng X, Cheng G. Phenol degradation and genotypic analysis of dioxygenase genes in bacteria isolated from sediments. Braz J Microbiol. 2017;48:305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich WR, Rigano C, Fuggi A, Aparicio PJ (Eds) (1990) Inorganic nitrogen in plants and microorganisms: uptake and metabolism. Springer, Berlin

- Wilberg KQ, Nunes DG, Rubio J. Removal of phenol by enzymatic oxidation and flotation. Braz J Chem Eng. 2000;17:4–7. doi: 10.1590/S0104-66322000000400055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]