Abstract

Unwanted sexual experiences are common among university students in the United States and pose a substantial public health concern. Campus policies and programs to prevent unwanted sexual incidents in university settings require research on prevalence and risk correlates of both victimization and perpetration. This study determined the prevalence of unwanted sexual victimization and perpetration experiences among students, both before and after joining the university, and examined risk correlates for both unwanted sexual victimization and perpetration experiences. Data were collected from 3,977 full-time graduate and undergraduate students using an online survey in a large private university. The findings revealed nearly one in eight students surveyed were victimized by unwanted sexual incidents at the university. Risk correlates of victimization by unwanted sexual incidents included female gender, undergraduate student status, and victimization experiences prior to joining the university. Most (95.5%) sexual violence incidents occurred when the victim was incapacitated due to alcohol, substance, or asleep. An acquaintance, peer, or colleague was the most frequently reported perpetrator. Risk correlates of perpetration included male gender, undergraduate student status, and perpetration of unwanted sexual activities before joining the university. Perpetrators most frequently reported perpetration of unwanted sexual behaviors against a current or former intimate partner or a stranger. The findings highlight the importance of enhanced efforts to reduce prevalence of unwanted sexual incidents, particularly among students most at risk for victimization and perpetration.

Keywords: sexual violence, victimization, perpetration, campus sexual assault

High-profile media cases have drawn attention to the high prevalence of unwanted and nonconsensual sexual behaviors on college campuses in the United States. Over the past many decades, national sexual misconduct surveys have consistently reported pervasive unwanted sexual experiences among female college students (e.g., Cantor et al., 2015; Fisher, Cullen, & Turner, 2000; Kilpatrick, Resnick, Ruggiero, Conoscenti, & McCauley, 2007; Koss, Gidyez, & Wisniewski, 1987), and national data illustrated that among U.S. adults experiencing sexual violence, the assault often occurred during college ages (18–24 years; Black et al., 2011). In one of the only nationally representative studies of sexual victimization on college campuses (Koss et al., 1987), nearly 54% of women self-reported experiencing sexual victimization, 28% reported experiencing sexual violence (i.e., rape or attempted rape), 25.1% of men reported acts of sexual aggression, and 7.7% reported committing rape or attempted rape (Koss et al., 1987). In a more recent Association of American Universities (AAU) nonrepresentative survey of students at 27 U.S. universities, 11.7% of students reported experiencing unwanted sexual behaviors by physical force or incapacitation since entering college and nearly 10% experienced sexual violence, with female students reporting higher rates than males among both undergraduate and graduate students (Cantor et al., 2015). The lower rates in the AAU study compared with that of Koss and colleagues (1987), potentially reflect increased awareness of the issue over time, or meaningful decreases in the prevalence of sexual violence. Other studies show an estimated 25% to 30% of college men acknowledge engaging in some form of sexual assault since age 14, an estimate that has been remarkably consistent over time (Koss et al., 1987; White et al., 2015; Zinzow & Thompson, 2015).

Sexual harassment, another form of sexual misconduct, includes inappropriate comments about a person’s body, appearance, or sexual behavior; sexual remarks; or insulting or offensive jokes. Recent data show that sexual harassment is also widespread on college campuses: 23% in the University of Michigan (2015) survey and 48% in the AAU survey (Cantor et al., 2015) In the AAU study, on average, 47.7% of students indicated sexual harassment victimization, with more than half of female undergraduates (61.9%) reporting sexual harassment. In a University of Oregon survey (2015; Freyd, 2015), sexual harassment was pervasive when perpetrated by fellow students (58% of female graduate students, 68% of female undergraduate), and faculty/staff (28% undergraduates to 38% graduate of female respondents) (Freyd, 2015).

Research Gap and Purpose of the Study

Although methodological differences make comparison of data across studies challenging, data consistently document prevalent sexual victimization among university students, particularly undergraduate females (Fisher et al., 2000; Krebs, Lindquist, Warner, Fisher, & Martin, 2007). Where perpetration is examined, data continue to show higher rates of sexual aggression among male than female college students. Within this work, few studies have used multivariate analysis or differentiated risk factors for victimization and perpetration between genders and level of education. Victim-perpetrator relationships are not always specified, despite other types of evidence that most sexual assaults are committed by someone known to the victim, often dating partners (Wegner, Pierce, & Abbey, 2014; White House Council on Women and Girls and the Office of (Abbey, McAuslan, Zawacki, Clinton, & Buck, 2001). Furthermore, the range of unwanted sexual experiences studied remains limited and has only recently begun to include sexual harassment. Finally, although experiences of sexual violence prior to university enrollment may be key risk factors, little research to date has explored this source of risk. Information on prevalence and risk correlates is critical for developing evidence-based policies and programs to prevent and respond to unwanted sexual incidents in universities.

To inform this evidence base, we (a) determine the prevalence of unwanted sexual victimization and perpetration experiences among students at one university, both before and since enrollment; and (b) examine risk correlates for unwanted sexual victimization and perpetration experiences. We define “unwanted and nonconsensual sexual behaviors” broadly to include sexual harassment, unwanted sexual contact (e.g., touching), and sexual violence (i.e., attempted or completed forced penetration).

Method

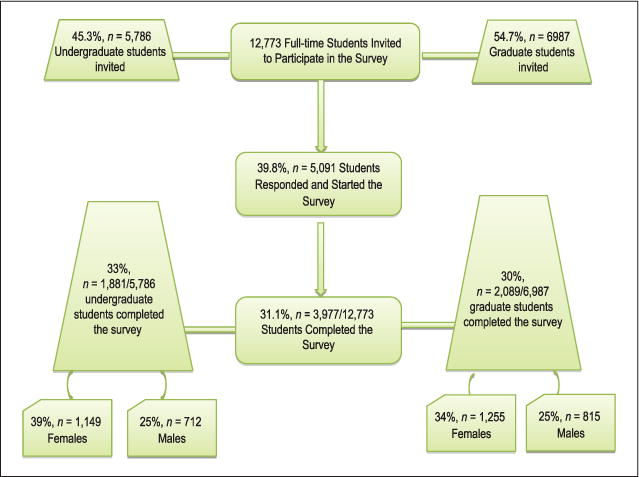

This cross-sectional study used data collected anonymously from 3,977 full-time graduate and undergraduate students in a large private university. The survey was administered using Qualtrics online software, following informed consent. Participants were recruited via email sent to 12,773 full-time students; and 5,091 students responded, consented, and started the survey; Figure 1. Out of these, 3,977 completed the survey, for an overall response rate of 31% (3,977/12,773). Students who completed the survey were entered in a raffle for a chance to win US$50, US$25, and US$10 prizes. All procedures were reviewed and approved by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Insititutional Review Board (IRB). Students who participated in the survey were provided with a list of resources including sexual assault hotline in accordance with the ethical guidelines.

Figure 1.

Survey flowchart.

Measures

Outcome measures

Victimization by unwanted sexual activities

Victimization by unwanted sexual activities was measured through self-reported experiences of (a) unwanted sexual contact, (b) sexual violence, and (c) sexual harassment.

Unwanted sexual contact: Unwanted sexual contact included unwanted touching (i.e., someone fondled, kissed, or rubbed up against the private areas of body or removed some clothes without consent).

Sexual violence: Sexual violence included actual or attempted oral, anal, or vaginal penetration by use of force or a weapon, or threat to physically harm the respondent or someone close, or when the victim could not consent because of intoxication (alcohol or drugs) or being asleep.

The five items that measured unwanted sexual contact and sexual violence were adapted from behaviorally specific questions in the Sexual Experiences-Short Form Victimization (SES-SFV; 10 items; Koss et al., 2006b). The items asked about both before and during university experiences. Response options included “yes once,” “more than once,” “no,” and “unsure.”

-

c

Sexual harassment: Sexual harassment was measured using one item that asked students if they ever experienced sexual harassment at the university, and seven behaviorally specific harassment items (e.g., said crude sexual things or tried to talk about sexual matters when the respondent didn’t want to; emailed, texted, or instant messaged offensive jokes).

Perpetration of unwanted sexual activities

This variable included self-reported (a) perpetration of unwanted sexual contact and (b) sexual violence. The five items were adapted from the Sexual Experiences–Short Form Perpetration (SES-SFP; 10 items; Koss et al., 2006a). The SES-SFP assesses frequency of engagement in sexually aggressive acts such as unwanted sexual contact, attempted sexual violence, and sexual violence since first attending the university. Definitions were consistent with those used for victimization. The questions were also asked referring to having engaged in experiences prior and after university enrollment as in the victimization items above.

Independent variables

Additional factors assessed included demographic characteristics (gender, student status [graduate vs. undergraduate], country of birth, and race/ethnicity). Those reporting victimizations and/or perpetration were asked to characterize the incident (relationship with the perpetrator/victim and location of the incident). Relationship with the perpetrator/victim categories were no prior relationship, acquaintance, peer or colleague, friend, former dating/sexual partner or spouse, professor. Location of incidents of victimization and/or perpetration included residential buildings on campus, nonresidential buildings on campus, off-campus places, incidents that occurred at another college/university, and other areas.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for participants’ characteristics and also for victimization and perpetration variables overall, and by student status, gender, or in their combination. Association between two categorical variables was assessed using either a Chi-square test or a Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. We analyzed data by students’ education status (graduate vs. undergraduate), and by gender (male vs. female) within students’ educational status. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression models examined the association of individual characteristics with victimization and perpetration outcomes. As appropriate, some categories of an independent variable with very small frequencies were combined to improve reliability of estimates and their standard errors. We used backward elimination regression method for multivariate models with risk factors that were significant at ≤.10 in univariate analysis. The following outcomes were analyzed: (a) victimization: unwanted sexual contact, sexual violence with different tactics, and sexual harassment; and (b) perpetration: unwanted sexual contact perpetration and sexual violence perpetration, regardless of tactic. Although all participants are included in describing participants’ characteristics and other descriptive statistics, gender minority participants were not included in inferential statistical analysis (logistic regression modeling) due to small cell sizes resulting in unreliable estimates. We also combined American Indian or Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamarro, Samoan and Other Pacific Islander students into the “Non-Hispanic Other” category due to small cell sizes. All statistical tests were two-sided and used alpha 0.05 for significance. Associations between victimization type and victim characteristics such as location of incident and perpetrator relationship were also explored among victims, using Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test due to small number of events per cell. Similar methods were used for perpetrator characteristics. The Qualtrics raw data were exported in SPSS format, and SAS 9.4 was used for all the data management and statistical analyses.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of 3,977 respondents, including 38.5% (n = 1,527) males, 60.7% (n = 2,404) females, and less than 1% (0.8%, n = 32) students from alternate gender identities, with missing data for gender on nine respondents, for student status on seven respondents and for both student status and gender on 14 respondents (Table 1). More than half of the respondents were graduate students (approximately 53%, n = 2,084). Most students identified as non-Hispanic Whites or Caucasians (51.8%, n = 2,052) followed by Asians (25.6%, n = 1,104). Slightly more than a quarter of the participants were foreign-born (26.7%, n = 1057) χ2(1, N = 3954) = 149.61.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (n = 3,977), n (%).

| Undergraduate Respondents (UG), n = 1,881

|

Graduate Respondents, n = 2,089

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Female (n = 1,149) | Male (n = 712) | p Value M vs. F | Alternate Gender (n = 18) | Total UG (n = 1,879) | Female (n = 1255) | Male (n = 815) | p Value M vs. F | Alternate Gender (n = 14) | Total Graduates (n = 2,084) | p Value Graduate vs. UG | Total Students (n = 3,963) | Missing (n = 14) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||||||

| NH White or Caucasian | 584 (52.4) | 347 (51.3) | .671 | 13 (72.2) | 944 (52.1) | 683 (57.0) | 415 (54.3) | .518 | 10 (76.9) | 1108 (56.1) | <.001 | 2,052 (51.8) | 2 |

| NH Black/African American | 56 (5.0) | 25 (3.7) | ** (**) | 83 (4.6) | 51 (4.2) | 33 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 84 (4.2) | 167 (4.2) | 2 | |||

| NH Asian | 263 (23.6) | 174 (25.7) | ** (**) | 438 (24.2) | 339 (28.3) | 237 (31.0) | 0 (0.0) | 576 (29.1) | 1,104 (25.6) | 3 | |||

| NH multirace | 70 (6.3) | 38 (5.6) | ** (**) | 110 (6.1) | 41 (3.4) | 23 (3.0) | ** (**) | 65 (3.3) | 175 (4.4) | 0 | |||

| NH Other | ** (**) | ** (**) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.4) | ** (**) | ** (**) | 0 (0.0) | ** (**) | 11 (0.3) | 0 | |||

| Hispanic (any race) | 138 (12.4) | 90 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | 228 (12.6) | 84 (7.0) | 53 (6.9) | ** (**) | 139 (7.0) | 367 (9.3) | 1 | |||

| Race/ethnicity missing | 34 | 35 | 0 | 69 | 56 | 51 | 1 | 108 | 177 | 6 | |||

| Birthplace | |||||||||||||

| Foreign-born | 198 (17.3) | 132 (18.6) | .472 | **(**) | 331 (17.7) | 399 (31.9) | 325 (39.9) | <.001 | ** (**) | 726 (34.9) | <.001 | 1057 (26.7) | 1 |

| U.S.-born | 948 (82.7) | 578 (81.4) | 17 (94.4) | 1543 (82.3) | 852 (68.1) | 490 (60.1) | 12 (85.7) | 1354 (65.1) | 2897 (73.3) | 9 | |||

| Birthplace data missing | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 4 | |||

| Victimization before coming to the university | |||||||||||||

| Unwanted sexual contact only | 154 (13.4) | 22 (3.1) | <.01 | 1 (5.6) | 177 (9.4) | 265 (21.2) | 60 (7.4) | <.001 | 2 (14.3) | 327 (15.7) | <.001 | 504 (12.7) | 3 |

| Sexual violence overall | 94 (8.2) | 11 (1.5) | <.01 | 2 (11.1) | 107 (5.7) | 181 (14.4) | 25 (3.1) | <.001 | 4 (28.6) | 210 (10.1) | <.001 | 317 (8.0) | 1 |

| Sexual violence by force or weapon | 29 (2.5) | 2 (0.3) | <.01 | 1 (5.6) | 32 (1.7) | 46 (3.7) | 3 (0.4) | <.001 | 3 (21.4) | 52 (2.5) | .084 | 84 (2.1) | 1 |

| Sexual violence by threat of physical harm | 12 (1.0) | 4 (0.6) | .273 | 1 (5.6) | 17 (0.9) | 24 (1.9) | 2 (0.2) | <.001 | 2 (14.3) | 28 (1.3) | .193 | 45 (1.1) | 1 |

| Sexual violence while intoxicated | 76 (6.6) | 9 (1.3) | <.01 | 1 (5.6) | 86 (4.6) | 152 (12.1) | 21 (2.6) | <.001 | 2 (14.3) | 175 (8.4) | <.001 | 261 (6.6) | 0 |

| Perpetration before coming to the university | |||||||||||||

| Unwanted sexual contact only | 2 (0.2) | 12 (1.7) | <.01 | 1 (5.6) | 15 (0.8) | 7 (0.6) | 18 (2.2) | <.001 | 0 (0.0) | 25 (1.2) | .207 | 40 (1.0) | 0 |

| Sexual violence overall | 6 (0.5) | 9 (1.3) | .082 | 2 (11.1) | 17 (0.9) | 2 (0.2) | 7 (0.9) | .033 | 0 (0.0) | 9 (0.4) | .066 | 26 (0.7) | 0 |

Note. NH = Non-Hispanic, missing values for student status = 7, gender = 9, student status and gender combination = 14 resulting into n = 3,963 that had self-report on gender and student status, cell frequency < 5 presented as

instead of actual number to prevent probable identification or deductive disclosure; there was no tactic data available on perpetration of unwanted sexual contact or sexual violence; p value from a chi-square test or a Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. UG = undergraduate; M vs. F = male vs. female.

Unwanted sexual contact (excluding sexual violence) victimization before joining the university was reported by 12.7% (n = 504). Sexual violence victimization before joining the university was reported by 8% (n = 317), including that while intoxicated or asleep (6.6%, n = 261), sexual violence by force or weapon (2.1%, n = 84), and by threat of physical harm (1.1%, n = 45). Victimization prior to university was more prevalent among females as compared with males, among both undergraduates and graduates students.

Univariate/Bivariate Results

Prevalence and characteristics of unwanted sexual victimization experiences

Among 3,977 total students who completed the survey (with n = 3,963 for self-report on gender and student status), 7.5% (n = 300) of students reported experiencing unwanted sexual contact using a verbal tactic (telling lies, verbally pressuring, catching off guard, etc.), without sexual violence, while at the university. Sexual violence (with or without unwanted sexual contact via verbal tactics) since joining the university was reported by 5% (n = 199), including those while intoxicated or asleep (4.8%, n = 190). About 9% participants (n = 365) reported experiencing sexual harassment. Victimization by unwanted sexual contact both before and after joining the university was reported by 2.1%, and sexual violence across both time periods was 1.2% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Victimization and Perpetration of Unwanted Sexual Activities (n = 3,977).

| Undergraduate Respondents (UG)

|

Graduate Respondents

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Female (n = 1,149) | Male (n = 712) | p Value M vs. F | Alternate Gender (n = 18) | Total UG Students (n = 1,879) | Female (n = 1,255) | Male (n = 815) | p Value M vs. F | Alternate Gender (n = 14) | Total Graduates (n = 2,084) | p Value Graduate vs. UG | Total Students (n = 3,963) | Missing (n = 14) |

| Victimization at the university | |||||||||||||

| Unwanted sexual contact only using a verbal tactica | 183 (15.9) | 38 (5.3) | <.0001 | 2 (11.1) | 223 (11.9) | 53 (4.2) | 22 (2.7) | 0.070 | 1 (7.1) | 76 (3.6) | <.0001 | 299 (7.5) | 1 |

| Sexual violence overall | 140 (12.2) | 12 (1.7) | <.0001 | 0 (0.0) | 152 (8.1) | 39 (3.1) | 8 (1.0) | 0.001 | 0 (0.0) | 47 (2.3) | <.0001 | 199 (5.0) | 0 |

| Sexual violence by force or weapon | 14 (1.2) | 1 (0.1) | .011 | 0 (0.0) | 15 (0.8) | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.159 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | .006 | 19 (0.5) | 0 |

| Sexual violence by threat of physical harm | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | >.999 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.4) | 0.307 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | .378 | 5 (0.1) | 0 |

| Sexual violence while intoxicated (alcohol, substance, or asleep) | 135 (11.7) | 12 (1.7) | <.0001 | 0 (0.0) | 147 (7.8) | 35 (2.8) | 8 (1.0) | 0.005 | 0 (0.0) | 43 (2.1) | <.0001 | 190 (4.8) | 0 |

| Sexual harassment behavior | 228 (19.8) | 21 (2.9) | <.0001 | 2 (11.1) | 251 (13.4) | 98 (7.8) | 15 (1.8) | < .0001 | 1 (7.1) | 114 (5.5) | <.0001 | 365 (9.2) | 1 |

| Victimization both before and at the university | |||||||||||||

| Unwanted sexual contact only | 52 (4.5) | 5 (0.7) | <.0001 | 0 (0.0) | 57 (3.0) | 21 (1.7) | 6 (0.7) | 0.066 | 0 (0.0) | 27 (1.3) | <.001 | 84 (2.1) | 0 |

| Sexual violence overall | 30 (2.6) | 1 (0.1) | <.0001 | 0 (0.0) | 31 (1.6) | 16 (1.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0.004 | 0 (0.0) | 17 (0.8) | .016 | 48 (1.2) | 0 |

| Perpetration at the university | |||||||||||||

| Unwanted sexual contact only | 11 (1.0) | 24 (3.4) | <.001 | 0 (0.0) | 35 (1.9) | 7 (0.6) | 10 (1.2) | 0.099 | 1 (7.1) | 18 (0.9) | .006 | 53 (1.3) | 0 |

| Sexual violence overall | 8 (0.7) | 15 (2.1) | .007 | 1 (5.6) | 24 (1.3) | 5 (0.4) | 7 (0.9) | 0.236 | 0 (0.0) | 12 (0.6) | .020 | 35 (0.9) | 1 |

| Perpetration both before and at the university | |||||||||||||

| Unwanted sexual contact only | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.7) | .033 | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.5) | 0.082 | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.2) | .635 | 11 (0.3) | 0 |

| Sexual violence overall | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | >.999 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 0.155 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | .432 | 6 (0.1) | 0 |

Note. Missing values for student status = 7, gender = 9, student status and gender combination = 14 resulting into n = 3,963 that had self-report on gender and student status.

The values in parentheses refers to total number of students who participated in the survey. Victimization note:

Verbal tactic either (a) catching off guard or ignoring nonverbal cues or looks; (b) telling lies, threatening to end the relationship, or to spread rumors or verbally pressuring; or (c) showing displeasure, criticizing sexuality or attractiveness, or getting angry. Perpetration note: There is no tactic data available on perpetration of unwanted sexual contact or sexual violence. General note: p value from a chi-square test or a Fisher’s exact test as appropriate, UG = undergraduate; M vs. F = male vs. female.

All forms of victimization were more prevalent among undergraduates relative to graduate students, including unwanted sexual contact via verbal tactics since university enrollment (11.9%, n = 223 among undergraduates relative to 3.6%, n = 76 among graduate students, p < .0001). Overall, sexual violence victimization was higher among undergraduate than graduate students—8.1%, n = 152 versus 2.3%, χ2(1, N = 3963) = 70.52, n = 47 p < .0001; as was sexual violence victimization while intoxicated—7.8%, n = 147 versus 2.1%, n = 43, χ2(1, N = 3963) = 71.82, p < .0001; and sexual harassment at the university—13.4%, n = 251 versus 5.5%, n = 114, χ2(1, N = 3963) = 73.52, p < .0001.

Victimization was also more prevalent among females relative to male students in most categories assessed. Among undergraduates, females were significantly more likely than males to report unwanted sexual contact since university enrollment (15.9% vs. 5.3%, p < .0001). Sexual violence victimization since joining the university was more prevalent for women than men among both undergraduate—12.2%, n = 140 females versus 1.7%, n = 12 males, χ2(1, N = 1861) = 64.60, p ≤ .0001—and graduate students—3.1%, n = 39 females versus 1.0%, n = 8 males, χ2(1, N = 2070) = 10.06, p < .0001. Females were significantly more likely than males to be victimized by sexual violence while intoxicated. Sexual harassment was also more prevalent for women than men among undergraduate—19.8%, n = 228 females versus 2.9%, n = 21 males, χ2(1, N = 1861) = 108.25, p < .0001—and graduate students—7.8%, n = 98 females versus 1.8%, n = 15 males, χ2(1, N = 2070) = 34.10, p < .0001 (Table 2).

Characteristics of unwanted sexual incidents

Among the 499 students reporting any incident, sexual violence incidents predominantly occurred on campus (64.6%, n = 128), whereas unwanted sexual contact occurred approximately evenly on and off campus (51.7% and 48.3%, respectively). Sexual violence perpetrators were predominantly characterized as an acquaintance, peer, colleague, or friend (60.8%, n = 121) followed by a stranger (24.1%, n = 48), and current or former intimate partner (14.6%, n = 29; Fisher’s exact p < .001). Perpetrators of unwanted sexual contact were similarly acquaintances (44.4%, n = 128), strangers (43.7%, n = 126), and current or former partners (10.4%, n = 30; Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of Incidents at the University, n (%).

| Incident Type (n = 499)a

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victimization Correlates/Characteristics | Unwanted Sexual Contact Only Overall (n = 300) | Sexual Violence Overall (n = 199) | p Value | Sexual Violence by Force or Weapon (n = 19) | Sexual Violence by Threat of Physical Harm (n = 5) | Sexual Violence While Intoxicated (n = 190) |

| Perpetrator type | ||||||

| Acquaintance, peer, colleague, or friend | 128 (44.4) | 121 (60.8) | < .001 | 7 (36.8) | 2 (40.0) | 118 (62.1) |

| Current or former partner | 30 (10.4) | 29 (14.6) | 5 (26.3) | 1 (20.0) | 24 (12.6) | |

| No relationship (stranger) | 126 (43.7) | 48 (24.1) | 6 (31.6) | 1 (20.0) | 47 (24.7) | |

| Academic related | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Family member or other | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Perpetrator data missing | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Location of incident | ||||||

| On campus | 149 (51.7) | 128 (64.6) | .005 | 12 (63.2) | 3 (60.0) | 123 (65.1) |

| Off campus | 139 (48.3) | 70 (35.3) | 7 (36.8) | 2 (40.0) | 66 (34.9) | |

| Location data missing | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Birthplace | ||||||

| Foreign-born | 48 (16.1) | 39 (19.6) | .316 | 4 (21.1) | 3 (60.0) | 37 (19.5) |

| U.S.-born | 250 (83.9) | 160 (80.4) | 15 (78.9) | 2 (40.0) | 153 (80.5) | |

| Birthplace data missing | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| NH White or Caucasian | 171 (58.0) | 104 (54.2) | .145 | 11 (61.1) | 1 (33.3) | 99 (54.1) |

| NH Black/African American | 17 (5.8) | 11 (5.7) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (5.5) | |

| NH Asian | 54 (18.3) | 25 (13.0) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (33.3) | 25 (13.7) | |

| NH multirace | 22 (7.5) | 19 (9.9) | 3 (16.7) | 1 (33.3) | 17 (9.3) | |

| NH Other | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hispanic (any race) | 30 (10.2) | 33 (17.2) | 2 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (17.5) | |

| Race/ethnicity missing | 5 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 7 | |

Note. NH = non-Hispanic.

Incident type here is either unwanted sexual contact only or sexual violence overall. As there were no follow-up questions for location of the incident and relationship with the perpetrator among those who said “yes” to being sexually harassed, the results for location and relationship are only presented for unwanted sexual contact and sexual violence outcomes. Denominators are now incidents only; p value from a chi-square test or a Fisher’s exact test as appropriate; missing category not included in testing.

Prevalence and characteristics of perpetration of unwanted sexual activities

Overall, 89 students reported perpetration of unwanted sexual activities at the university. Of the total sample 1.3% (n = 53) students reported perpetration of unwanted sexual contact, and 0.9% (n = 35) reported perpetration of sexual violence while at the university. Among undergraduates, males were more likely than females to report perpetration of unwanted sexual contact—3.4%, n = 24 males versus 1.0%, n = 11 females, χ2(1, N = 1861) = 13.88, p < .001—and overall sexual violence—2.1% males, n = 15 versus 0.7%, n = 8 females, χ2(1, N = 1861) = 7.16 p = .007. Undergraduate students were significantly more likely than graduate students to report perpetration of unwanted sexual contact—1.9%, n = 35 undergraduate versus 0.9%, n = 18 graduate students, χ2(1, N = 3963) = 7.47, p = .006—and overall sexual violence—1.3%, n = 24 undergraduates versus 0.6%, n = 12 graduate students, χ2(1, N = 3963) = 5.40, p = .020 (Table 2).

Among those who self-reported perpetration of unwanted sexual activities (Table 4), the most frequently reported victim of unwanted sexual contact (45.1%, n = 23) was a current or former partner, whereas the most frequently reported victim of sexual violence was a stranger (50.0%, n = 14; Fisher’s exact p = .005). Perpetration of both unwanted sexual contact and sexual violence occurred more frequently in off campus than on campus settings. Among those reporting perpetration, unwanted sexual contact perpetrators were more commonly U.S.-born (86.8% n = 46) relative to 69.4% (n = 25) of sexual violence—χ2(1, N = 89) = 4.00, p = .045.

Table 4.

Characteristics of Perpetrators of Incidents at the University, n (%).

| Incident Type (n = 89)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Perpetrator Characteristics | Unwanted Sexual Contact Only Overall (n = 53) | Sexual Violence Overall (n = 36) | p Value |

| Victim type | |||

| Acquaintance, peer, | 13 (25.5) | 2 (7.1) | .005 |

| colleague, or friend | |||

| Current or former partner | 23 (45.1) | 8 (28.6) | |

| No relationship (stranger) | 15 (29.4) | 14 (50.0) | |

| Academic related | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.7) | |

| Family member or other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.6) | |

| Victim data missing | 2 | 8 | |

| Location of incident | |||

| On campus | 19 (37.2) | 12 (40.0) | .817 |

| Off campus | 32 (62.8) | 18 (60.0) | |

| Location data missing | 2 | 6 | |

| Birthplace | |||

| Foreign-born | 7 (13.2) | 11 (30.6) | .045 |

| U.S.-born | 46 (86.8) | 25 (69.4) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| NH White or Caucasian | 33 (64.7) | 13 (38.2) | .087 |

| NH Black/African American | 5 (9.8) | 3 (8.8) | |

| NH Asian | 8 (15.7) | 9 (26.5) | |

| NH multirace | 2 (3.9) | 2 (5.9) | |

| Hispanic (any race) | 3 (5.9) | 7 (20.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity missing | 2 | 2 | |

Note. NH = non-Hispanic.

Incident type here is self-reported perpetration of either unwanted sexual contact only or sexual violence overall. Denominators are now incidents only; p value from a chi-square test or a Fisher’s exact test as appropriate; missing category not included in testing.

Nearly 2% (1.7%; n = 66) reported perpetration of either unwanted sexual contact (n = 40) or sexual violence (n = 26) before attending the university. Of 26 sexual violence perpetrators before the university, 61.5% (n = 16) were males and 30.8% (n = 8) were females, with 7.7% (n = 2) of an alternate gender (Table 1). Among those who perpetrated sexual violence before joining the university (n = 26), 23.1% (n = 6) perpetrated sexual violence at the university. Among 40 students who self-reported perpetrating unwanted sexual contact prior to joining the university, 27.5% (n = 11) reported perpetrated unwanted sexual contact at the university (Table 2).

Logistic Regression Results

Factors associated with victimization

Unwanted sexual contact victimization

The final multivariate logistic regression model selected using backward elimination included gender, student status, birthplace, and previous incident of unwanted sexual contact (Table 5). After controlling for other covariates, factors associated with unwanted sexual contact included female gender (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.21, 95% confidence interval, [CI] = [1.63, 3.00]), undergraduate status (AOR = 4.04, 95% CI = [3.03, 5.38]), and past experiences of unwanted sexual contact (AOR = 3.36, 95% CI = [2.50, 4.52]); being foreign-born was protective (AOR = 0.69, 95% CI = [0.49, 0.96]).

Table 5.

Factors Related to Victimization by Unwanted Sexual Activities at the University.

| Unwanted Sexual Contact Victimization (n = 297)

|

Overall Sexual Violence Victimization (n = 199)

|

Sexual Harassment Victimization (n = 363)

|

Sexual Violence Victimization While Intoxicated or Asleep (n = 190)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Univariate OR (95% CI) | Multivariate AOR (95% CI) (n = 289) | Univariate OR (95% CI) | Multivariate AOR (95% CI) (n = 192) | Univariate OR (95% CI) | Multivariate AOR (95% CI) (n = 348) | Univariate OR(95% CI) | Multivariate AOR (95% CI) (n = 183) |

| Female | 2.62*** [1.96, 3.49] | 2.21*** [1.63, 3.00] | 6.06*** [3.80, 9.67] | 5.98*** [3.59, 9.96] | 6.32*** [4.47, 8.93] | 6.39*** [4.47, 9.15] | 5.73*** [3.59, 9.15] | 5.64*** [3.38, 9.40] |

| Male (Ref.) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Undergraduate | 3.59*** [2.74, 4.70] | 4.04*** [3.03, 5.38] | 3.83*** [2.75, 5.35] | 4.47*** [3.11, 6.42] | 2.68*** [2.12, 3.38] | 2.66*** [2.09, 3.40] | 4.05*** [2.86, 5.72] | 4.86*** [3.33, 7.09] |

| Graduate (Ref.) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.26 [0.74, 2.13] | — | 1.31 [0.69, 2.48] | 1.33 [0.69, 2.59] | 0.80 [0.45, 1.41] | 0.67 [0.37, 1.23] | 1.24 [0.64, 2.43] | 1.26 [0.63, 2.53] |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.62** [0.45, 0.85] | 0.47*** [0.30, 0.73] | 0.55* [0.35, 0.87] | 0.50*** [0.37, 0.68] | 0.52*** [0.38, 0.71] | 0.49** [0.31, 0.77] | 0.59* [0.37, 0.93] | |

| Non-Hispanic Multirace | 1.63* [1.01, 2.61] | 2.30** [1.37, 3.85] | 1.98* [1.15, 3.40] | 1.49 [0.95, 2.33] | 1.22 [0.76, 1.95] | 2.14** [1.25, 3.67] | 1.87* [1.06, 3.29] | |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 1.11 [0.14, 8.71] | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Hispanic | 0.99 [0.66, 1.48] | 1.84** [1.22, 2.76] | 1.63* [1.06, 2.50] | 1.32 [0.95, 1.85] | 1.18 [0.83, 1.68] | 1.87* [1.23, 2.83] | 1.66* [1.07, 2.58] | |

| Non-Hispanic White (Ref.) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Foreign-born | 0.51*** [0.37, 0.70] | 0.69* [0.49, 0.96] | 0.65* [0.46, 0.93] | — | 0.50*** [0.38, 0.67] | — | 0.65* [0.45, 0.93] | — |

| U.S.-born (Ref.) | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| Incident (unwanted contact or sexual violence) before university |

3.03*** [2.31, 3.98] — |

3.36*** [2.50, 4.52] — |

4.19*** [2.96, 5.94] — |

3.64*** [2.47, 5.38] — |

— | — |

4.82*** [3.34, 6.95] — |

4.41*** [2.91, 6.68] — |

| Yes | ||||||||

| No (Ref.) | ||||||||

| Pseudo-R2 | — | 5.50% | — | 6.00% | — | 6.60% | 5.90% | |

Note. OR refers to estimated odds ratio from a univariate logistic regression model, and AOR refers to adjusted odds ratios calculated using multivariate logistic regression model. Numbers of an incident in this table do not include alternate gender, and missing category for a predictor variable is ignored. Sexual violence by force or weapon, and sexual violence by threat of physical harm, so only sexual violence victimization while intoxicated was modeled as victimization by tactic. Sexual harassment before joining the university was not collected. CI = confidence interval.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Sexual violence victimization

The final model included gender, student status, race/ethnicity, and experiences of sexual violence prior to joining the university. Factors associated with sexual violence victimization included female gender (AOR = 5.98, 95% CI = [3.59, 9.96]), undergraduate status (AOR = 4.47, 95% CI = [3.11, 6.42]), past experiences of sexual violence prior to the university (AOR = 3.64, 95% CI = [2.47, 5.38]). Relative to non-Hispanic white students, Asian race was protective (AOR = 0.55, 95% CI = [0.35, 0.87]), and multiple races/ethnicities (AOR = 1.98, 95% CI = [1.15, 3.40]) and Hispanic (AOR = 1.63, 95% CI = [1.06, 2.50]) conferred risk.

Sexual harassment

The selected model for sexual harassment only included gender, student status, and race/ethnicity; experience of sexual harassment before joining the university was not available as a covariate. Factors associated with sexual harassment included female gender (AOR = 6.39, 95% CI = [4.47, 9.15]), and undergraduate status (AOR = 2.66, 95% CI = [2.09, 3.40]); Asian race conferred protection relative to White students (AOR = 0.52, 95% CI = [0.38, 0.71]).

Sexual violence victimization while intoxicated/asleep

The selected multivariate model included gender, student status, race/ethnicity, and previous incident of sexual violence while intoxicated. Sexual violence victimization while incapacitated was associated with female gender (AOR = 5.64, 95% CI = [3.38, 9.40]), undergraduate status (AOR = 4.86, 95% CI = [3.33, 7.09]), and victimization prior to joining the university (AOR = 4.41, 95% CI = [2.91, 6.68]). Asian race was protective relative to White (AOR = 0.59, 95% CI = [0.37, 0.93]; Table 5), while multiple races/ethnicities (AOR = 1.87, 95% CI = [1.06, 3.29]; Table 5) and Hispanics were at higher risk (AOR = 1.66, 95% CI = [1.07, 2.58]; Table 5).

Factors associated with perpetration

Perpetration of unwanted sexual contact was associated with male gender (AOR = 2.32, 95% CI = [1.27, 4.25]), undergraduate status (AOR = 2.52, 95% CI = [1.36, 4.68]), and unwanted sexual contact perpetration prior to the university (AOR = 30.71, 95% CI = [13.24, 71.24]; Table 6). Sexual violence perpetration was similarly associated with male gender (AOR = 2.59, 95% CI = [1.25, 5.36]), undergraduate status (AOR = 2.12, 95% CI = [1.01, 4.44]), and past perpetration (AOR = 29.81, 95% CI = [10.02, 88.66]).

Table 6.

Factors Related to Perpetration of Unwanted Sexual Activities at the University.

| Predictor | Perpetration of Unwanted Sexual Contact Only (n = 5 2)a

|

Perpetration of Sexual Violence Overall (n = 34)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Univariate OR (95% CI) | Multivariate AOR (95% CI) | Univariate OR (95% CI) | Multivariate AOR (95% CI) |

| Male perpetrator | 3.02*** [1.70, 5.36] | 2.32** [1.27, 4.25] | 2.69** [1.35, 5.35] | 2.59** [1.25, 5.36] |

| Female perpetrator (Ref.) | ||||

| Undergraduate perpetrator | 2.32** [1.29, 4.15] | 2.52** [1.36, 4.68] | 2.15* [1.07, 4.33] | 2.12* [1.01, 4.44] |

| Graduate perpetrator (Ref.) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.93 [0.74, 5.01] | 3.08 [0.86, 11.02] | ||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.50 [0.23, 1.08] | 1.50 [0.63, 3.58] | ||

| Non-Hispanic Multirace | 0.73 [0.17, 3.09] | 1.98 [0.44, 8.92] | ||

| Hispanic | 0.52 [0.16, 1.69] | 3.28* [1.28, 8.39] | ||

| Non-Hispanic White (Ref.) | — | — | ||

| Foreign-born perpetrator | 0.42* [0.19, 0.93] | 1.25 [0.61, 2.57] | ||

| U.S.-born (Ref.) | — | — | ||

| Incident (unwanted contact or sexual violence perpetration) before university | 37.03*** [17.28, 79.37] | 30.71*** [13.24, 71.24] | 44.73*** [16.56, 120.81] | 29.81*** [10.02, 88.66] |

| Yes | — | — | ||

| No (Ref.) | ||||

| Pseudo-R2 | — | 1.9% | — | 1.1% |

Note. The results for multivariate model above are presented using simultaneous regression procedure. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; AOR = adjusted odds ratio.

One student with unwanted sexual contact and two students with sexual violence perpetration did not report one of the risk factors.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Discussion

Nearly one in eight students who completed the survey reported experiencing some type of unwanted sexual behavior at the university. Our prevalence of unwanted sexual contact only (11.9%) and sexual violence overall (8.1%) (0.8% by force or weapon and 7.8% while intoxicated/asleep; Table 2) among female undergraduates is lower than the AAU survey across 27 universities in which 23% of female undergraduate students experienced unwanted sexual contact or sexual violence by force or incapacitation (Cantor et al., 2015; Johns Hopkins University, 2016). We believe our prevalence more accurately reflects prevalence, at least at this university, as the measurement used sexual assault measures validated in existing general sexual assault research rather than created specifically for universities. In our survey, as in most studies on and off campus, females were significantly more likely than males to report experiences of sexual violence and sexual harassment (Cantor et al., 2015; The University of Oregon survey, 2015). Our study, one of the few to include graduate students found undergraduate students significantly more likely than graduate students to report experiencing unwanted sexual contact and sexual harassment. Female undergraduate students were the most victimized group, with more than a quarter experiencing unwanted sexual contact using verbal pressure tactics or sexual violence using force or weapon, threat of physical harm, or taken advantage of when intoxicated or asleep. Most (96.4%) female undergraduate students who experienced sexual violence were victimized when they were incapacitated due to intoxication or sleep, rather than forced to have sex using physical force or a weapon, an important finding with implications for prevention of campus sexual assault programs and the depiction of the nature of most campus sexual assault. Research on university student samples, in general, has demonstrated similar risk factors associated with sexual victimization, that is female gender, alcohol use, undergraduate (vs. graduate) student status, and types of social events in which students engage (e.g., events involving use of alcohol; Abbey, 2002; Flack et al., 2008; Flack et al., 2007; Testa & Livingston, 2009; The University of Michigan, 2015).

Sexual violence incidents were significantly more likely than other types of violence incidents to have occurred on campus than off campus, with someone known (i.e., an acquaintance, peer, or colleague) being the most frequently reported perpetrator, again similar to most comparable studies (Abbey et al., 2001; Wegner et al., 2015). However, the 14.6% of the students who were sexually victimized by a current or former intimate partner is an important segment not frequently reported or considered separately with different dynamics and different prevention strategies than those victimized by acquaintances or strangers. Living in close proximity and trust of the perpetrator, despite potentially being in danger, may play a role in greater victimization by sexual violence versus unwanted sexual contact by someone known.

In our study, Asian students were significantly less likely than White students to report sexual harassment. This may be due to underreporting by Asian students or due to cultural differences in perceptions of harassment behaviors. Limited research has shown that Asian American women often feel vulnerable and helpless and wish to remain invisible if sexually harassed (Chan, 1987). Asian students were also less likely to report sexual violence, consistent with past research (Peters, 2012). Asians are less likely to seek help for their victimizations. Asian women in one study reported experiencing distrust, worthlessness, self-blame, shame, and guilt about being a victim likely due to having to cope with racial and cultural stereotypes about Asian women in addition to the harassment experience, making them less likely to seek help. This remains an area for further exploration, as there is a lack of research on the effects of trauma among Asian American groups, including interpersonal violence (Archambeau et al., 2010).

Experience of unwanted sexual behaviors before joining the university was reported by close to one in four participants, predominantly women. Many of those affected by unwanted sexual behaviors at the university had also experienced unwanted sexual experiences in the past. As individuals with prior experiences of sexual victimization are more likely than others to be revictimized (Classen, Palesh, & Aggarwal, 2005; Messman-Moore & Long, 2000), students with before university victimization experiences may be at high risk for being revictimized and an important target for prevention efforts. Understanding this potential for revictimization, or chronic experiences of violence both prior to and at the university setting, can help optimize the sexual violence response for support providers. Prevention programs should address both primary and secondary prevention, and can take a trauma-informed lens to recognize the potential for past experiences of victimization.

Although very few students reported perpetration, most surveys have not queried using sexual violence at all on campus so that even these limited findings are important and further support the female and undergraduate predominance of all types of sexual victimization. Importantly, perpetrators more frequently characterized their victims as current or former intimate partners for unwanted sexual contact, while sexual violence was more likely directed at strangers. Previous studies have shown that a majority of self-reported perpetrators of sexual violence acknowledge perpetrating violence against an intimate partner (Abbey et al., 2001; Wegner et al., 2014), but these studies did not contrast unwanted sexual contact with sexual violence. Some students described patterns of perpetration both prior to joining the university and during their time at the university, with greater numbers and greater proportions of male offenders being repeat offenders. Despite small numbers, perpetration prior to university increased the likelihood of perpetration while at the university, consistent with the findings of a recent research by (Swartout, Koss et al., 2015), but not addressed in most studies. This also has implications for sexual assault prevention strategies, suggesting that universal sexual assault training may well be ineffective for those who have perpetrated sexual assault in the past. As sexual assault perpetrators outside of universities are likely to have been victimized by experiencing violence and other Adverse Childhood Events (ACEs) in childhood, targeted interventions to help heal from that trauma for those so victimized may be needed Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Coker (SAMHSA) trauma website.

Implications

In addition to targeted trauma interventions, improving the campus environment requires attention to both prevention and support services, particularly for female undergraduate students given their disproportionate burden. Students in this setting have a variety of support resources available to them. Although support services are a critical component of a comprehensive response to violence both within and beyond university campuses, not all students may be aware of these resources and/or may not define unwanted sexual experiences as sexual assault or rape (Kahn, Jackson, Kully, Badger, & Halvorsen, 2003). Thus, policies and programs must be in place to promote awareness and to sensitize the campus community about unwanted sexual experiences using evidence-based strategies. Policies should focus on areas such as mandatory training for incoming freshman on sexual assault prevention resources, ongoing programs throughout the year to ensure sufficient exposure, and infrastructure to prevent unwanted sexual incidents and to support survivors (Dills, Fowler, & Payne, 2016). It is critically important to partner with stakeholders both on and off campus such as student health services, wellness centers, and local emergency departments, as these entities often serve as frontline responders for survivors of unwanted sexual incidents (Dills et al., 2016).

Perpetration prevention is also critical. In many higher education institutions, alcohol policies and bystander interventions (Coker et al., 2015; Kleinsasser, Jouriles, McDonald, & Rosenfield, 2015; McMahon, Banyard, & McMahon, 2015; Palm Reed, Hines, Armstrong, & Cameron, 2015) have been instituted. As the majority of the sexual violence incidents occurred due to alcohol intoxication, other interventions are also necessary. Training on core concepts related to consent and rape culture has been the focus of other intervention approaches, including the Campus Craft gaming intervention (Jozkowski & Ekbia, 2015). Addressing perpetration through adjusting culture and consent clarification can include helping students (particularly males) to recognize when they might be overstepping boundaries. This applies especially in terms of recognizing the inability to consent to sex if the other person is asleep and/or intoxicated, as well as making someone uncomfortable with their actions, or engaging in behavior or talk that promotes violence against and sexualization of female students. Some sexual assault prevention programs have faced criticism for placing too much onus on females to prevent sexual assault without including potential male perpetrators in prevention activities (O’Leary & Slep, 2012). Reduction of such victimization will likely be achieved with a greater focus on changing male student attitudes toward females in addition to the university policies and resources currently in place.

The limitations of the study include lack of information on key variables, primarily for space considerations, specifically sexual harassment characteristics including location of incident and perpetrator relationship, and perpetration of sexual harassment. Data were not collected on tactics of self-reported perpetration of unwanted sexual contact and sexual violence, nor sexual orientation, nor additional risk factors for sexual aggression perpetration, including childhood abuse, juvenile delinquency, exposure to domestic violence, hostile attitudes toward women, and peer group values supportive of violence against women (Knight & Sims-Knight, 2011 ; White et al., 2015). Related factors such as social desirability may have influenced self-report of intimate partner violence (IPV) perpetration (e.g., Rosenbaum & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2006). Small cell sizes resulted in unstable estimates in some cases. Despite efforts to ensure participant comfort in honest disclosure, data are subject to error as well as potential biases. Despite the limitations, this research is an important contribution to the literature on correlates of unwanted sexual incidents in university settings, and clarifying the extent and influence of preuniversity experiences of unwanted sexual contact.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Johns Hopkins University (JHU Provost Office). Dr. Sabri was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (K99HD082350).

Biographies

Jacquelyn C. Campbell, PhD, is the Anna D. Wolf Chair and Professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. She has 30 years of experience as a researcher, clinician, and educator in the area of violence against women with multiple studies of physical and mental health consequences of intimate partner violence (IPV), sexual assault, reproductive coercion, and abuse during pregnancy, as well as developing and testing culturally appropriate interventions to improve health care and community response to victims of IPV and co-occurring health inequities among vulnerable populations. She has authored or coauthored more than 240 publications and seven books.

Bushra Sabri, MSW, PhD, is a research associate faculty member at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. She has extensive cross-cultural and cross-national experiences in health care and social service settings. She has conducted multiple federally funded studies on interpersonal violence across the life span, and health outcomes of violence. Her current research focuses on the intersecting epidemics of violence, HIV, reproductive and sexual health problems among women, role of physiological stress responses in coping and adaptation to traumatic life events, and development and testing of trauma-informed culturally tailored interventions for at-risk women from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Chakra Budhathoki, PhD, is an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing (JHSON). He is a broadly trained applied statistician, an expert in the design, analysis, and reporting of both experimental research and observational studies. He has worked as a biostatistician with biomedical researchers in heart failure and HIV/AIDS and with nursing researchers in different topics. He also provides statistical consulting service to faculty and doctoral student researchers at JHSON. He was the study statistician for this campus health and safety study.

Michelle R. Kaufman, MA, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Health, Behavior & Society at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. As a social psychologist by training, she has been studying violence against women, gender disparities in sexual health, and sex trafficking for more than 12 years. Her research has spanned multiple continents, with projects focused on gendered health disparities in Nepal, India, South Africa, Tanzania, Ethiopia, and the United States.

Jeanne Alhusen, PhD, is an associate professor of nursing and assistant dean for research at University of Virginia School of Nursing. Her research is focused on improving maternal mental health and, consequently, improving early childhood outcomes, particularly for families living in poverty. Her research is funded by National Institute of Health (NIH), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and several foundation grants and seeks to elucidate the role of psychosocial risk factors on maternal, neonatal, and early childhood outcomes.

Michele R. Decker, ScD, MPH, is an associate professor in the Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. A social epidemiologist by training, her research focuses on gender-based violence, its prevention, and its implications for sexual and reproductive health. Her work includes clinic-based intervention efforts to mitigate the health consequences of violence, as well as primary research to understand the mechanisms by which violence influences sexual health and HIV risk. She works domestically as well as in South and Southeast Asia, and Eastern Europe/Central Asia.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abbey A. Alcohol-related sexual assault: A common problem among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Suppl. 14):118–128. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.118. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4484270/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, Zawacki T, Clinton AM, Buck PO. Attitudinal, experiential, and situational predictors of sexual assault perpetration. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:784–807. doi: 10.1177/088626001016008004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archambeau OG, Frueh BC, Deliramich AN, Elhai JD, Grubaugh AL, Herman S, Kim BSK. Interpersonal violence and mental health outcomes among Asian American and native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander college students. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010;2:273–283. doi: 10.1037/a0021262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Stevens MR. 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) [Google Scholar]

- Cantor D, Fisher B, Chibnall S, Townsend R, Lee H, Bruce C, Thomas G. Report on the AAU campus climate survey on sexual assault and sexual misconduct. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.aau.edu/uploadedFiles/AAU_Publications/AAU_Reports/Sexual_Assault_Campus_Survey/AAU_Campus_Climate_Survey_12_14_15.pdf.

- Chan CS. Asian-American women: Psychological responses to sexual exploitation and cultural stereotypes. Women & Therapy. 1987;6(4):33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Classen CC, Palesh OG, Aggarwal R. Sexual revictimization: A review of the empirical literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2005;6:103–129. doi: 10.1177/1524838005275087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Fisher BS, Bush HM, Swan SC, Williams CM, Clear ER, DeGue S. Evaluation of the Green Dot bystander intervention to reduce interpersonal violence among college students across three campuses. Violence Against Women. 2015;21(12):1507–1527. doi: 10.1177/1077801214545284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dills J, Fowler D, Payne G. Sexual violence on campus: Strategies for prevention. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Cullen FT, Turner MG. The sexual victimization of college women. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs; 2000. p. 20531. [Google Scholar]

- Flack WF, Jr, Caron ML, Leinen SJ, Breitenbach KG, Barber AM, Brown EN, Stein HC. “The Red Zone”: Temporal risk for unwanted sex among college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1177–1196. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flack WF, Jr, Daubman KA, Caron ML, Asadorian JA, D’Aureli NR, Gigliotti SN, Stein ER. Risk factors and consequences of unwanted sex among university students: Hooking up, alcohol, and stress response. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22:139–157. doi: 10.1177/0886260506295354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyd J. Initial findings from the UO 2015 sexual violence survey. 2015 Retrieved from http://media.oregonlive.com/education_impact/other/Final%20Freyd%20IVAT%202015%20UO%20Survey%20Initial%20Findings%2024%20August%202015%5B2%5D.pdf.

- Johns Hopkins University. “It’s on Us Hopkins” sexual violence climate survey: Principal findings. Baltimore, MD: Author; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jozkowski KN, Ekbia HR. “Campus craft”: A game for sexual assault prevention in universities. Games for Health. 2015;4:95–106. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2014.0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn AS, Jackson J, Kully C, Badger K, Halvorsen J. Calling it rape: Differences in experiences of women who do or do not label their sexual assault as rape. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2003;27:233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Ruggiero KJ, Conoscenti LM, McCauley J. Drug-facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape: A national study (Report by Medical University of South Carolina) Charleston, SC: National Crime Victims Research & Treatment Center; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinsasser A, Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Rosenfield D. An online bystander intervention program for the prevention of sexual violence. Psychology of Violence. 2015;5:227–235. doi: 10.1037/a0037393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight R, Sims-Knight J. Risk factors for sexual violence. In: White JW, Koss MP, Kazdin AE, editors. Violence against women and children, Vol 1: Mapping the terrain. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2011. pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, White J. The Sexual Experiences–Short Form Perpetration (SES-SFP) Tucson: University of Arizona; 2006a. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, White J. The Sexual Experiences–Short Form Victimization (SES-SFV) Tucson: University of Arizona; 2006b. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidyez CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs CP, Lindquist CH, Warner TD, Fisher BS, Martin SL. The Campus Sexual Assault Study. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon S, Banyard VL, McMahon SM. Incoming college students’ bystander behaviors to prevent sexual violence. Journal of College Student Development. 2015;56:488–493. [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Long PJ. Child sexual abuse and revictimization in the form of adult sexual abuse, adult physical abuse, and adult psychological maltreatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:489–502. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Slep AM. Prevention of partner violence by focusing on behaviors of both young males and females. Prevention Science. 2012;13:329–339. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm Reed KM, Hines DA, Armstrong JL, Cameron AY. Experimental evaluation of a bystander prevention program for sexual assault and dating violence. Psychology of Violence. 2015;5:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Peters B. Analysis of college campus rape and sexual assault reports, 2000–2011. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.mass.gov/eopss/docs/ogr/lawenforce/analysis-of-college-campus-rape-and-sexual-assault-reports-2000-2011-finalcombined.pdf.

- Rosenbaum A, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. Meta-research on violence and victims: The impact of data collection methods on findings and participants. Violence and Victims. 2006;21:404–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartout KM, Koss MP, White JW, Thompson MP, Abbey A, Bellis AL. Trajectory analysis of the campus serial rapist assumption. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169:1148–1154. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartout KM, Swartout AG, Brennan CL, White JW. Trajectories of male sexual aggression from adolescence through college: A latent class growth analysis. Aggressive Behavior. 2015;41(5):467–477. doi: 10.1002/ab.21584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA. Alcohol consumption and women’s vulnerability to sexual victimization: Can reducing women’s drinking prevent rape? Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:1349–1376. doi: 10.1080/10826080902961468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The University of Michigan. Results of 2015 University of Michigan campus climate survey on sexual misconduct. 2015 Retrieved from https://publicaffairs.vpcomm.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2015/04/Complete-survey-results.pdf.

- Wegner R, Pierce J, Abbey A. Relationship type and sexual precedence: Their associations with characteristics of sexual assault perpetrators and incidents. Violence Against Women. 2014;20:1360–1382. doi: 10.1177/1077801214552856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner R, Abbey A, Pierce J, Pegram SE, Woerner J. Sexual assault perpetrators’ justifications for their actions: Relationships to rape supportive attitudes, incident characteristics, and future perpetration. Violence Against Women. 2015;21(8):1018–1037. doi: 10.1177/1077801215589380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JW, Koss MP, Abbey A, Thompson M, Cook S, Swartout KM. What you need to know about campus sexual assault perpetration. 2015 Retrieved from https://marketing-production.cdn.ranenetwork.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/29151227/Facts-about-perpetration-with-logo_07_01-15.pdf.

- Zinzow HM, Thompson M. A longitudinal study of risk factors for repeated sexual coercion and assault in U.S. college men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015;44:213–222. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]